Consumers’ Behavioral Willingness to Use Green Financial Products: An Empirical Study within a Theoretical Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

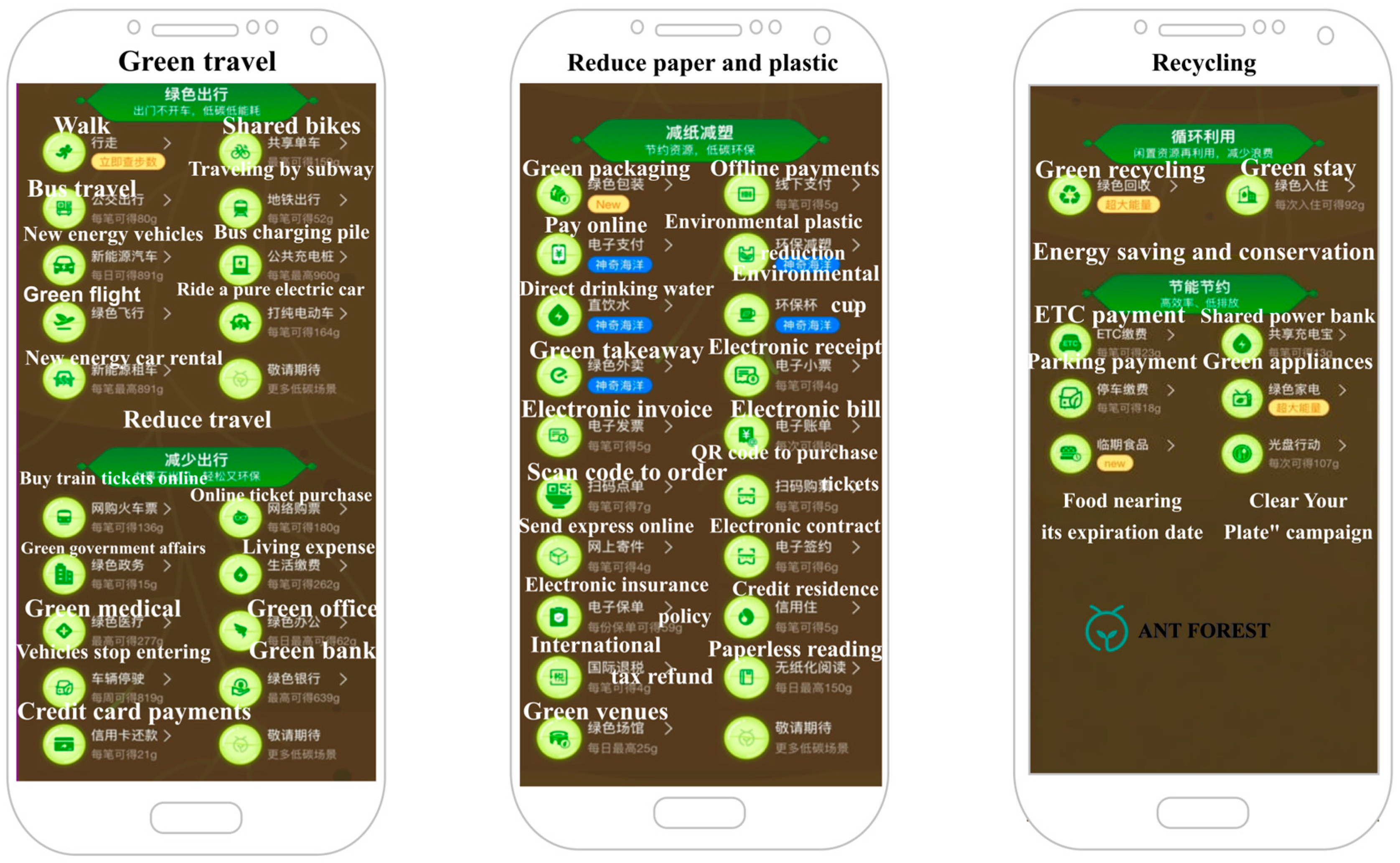

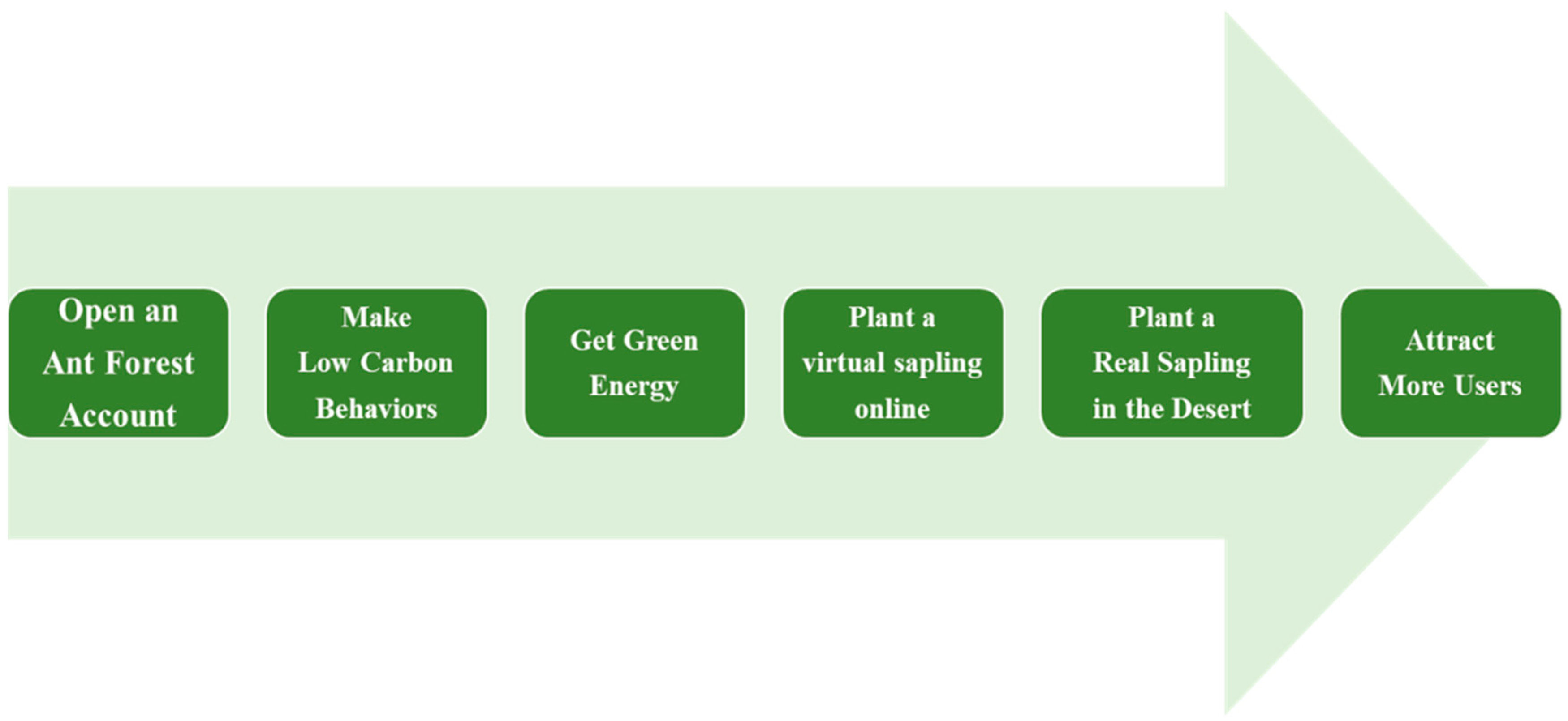

2.1. Green Financial Products and Ant Forest

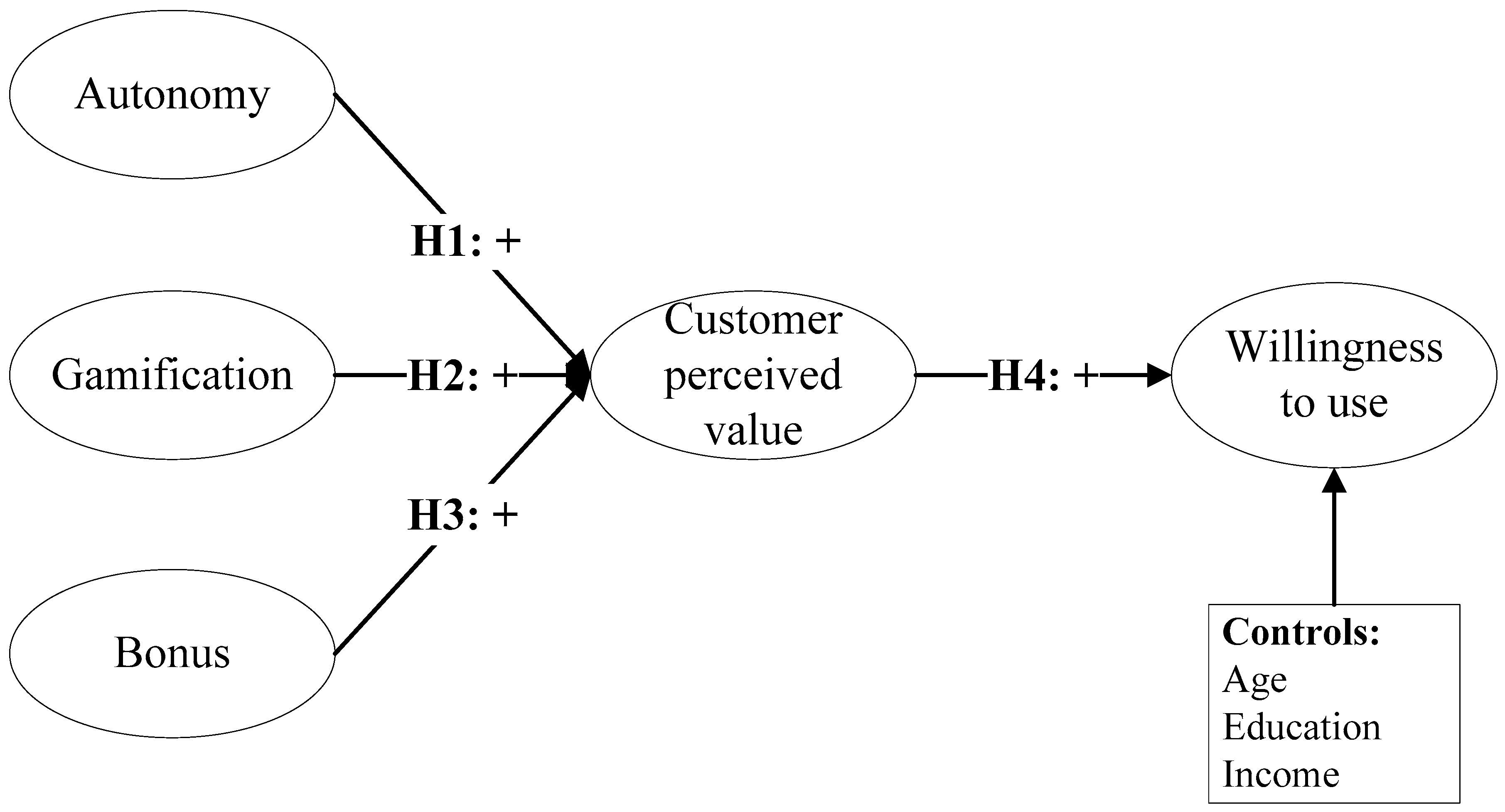

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. Self-Determination Theory

2.3.1. Autonomy

2.3.2. Gamification

2.3.3. Bonus

2.4. Customer-Perceived Value and Technology Acceptance Model

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Survey Design

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Bias Tests

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Measurement Model Analysis

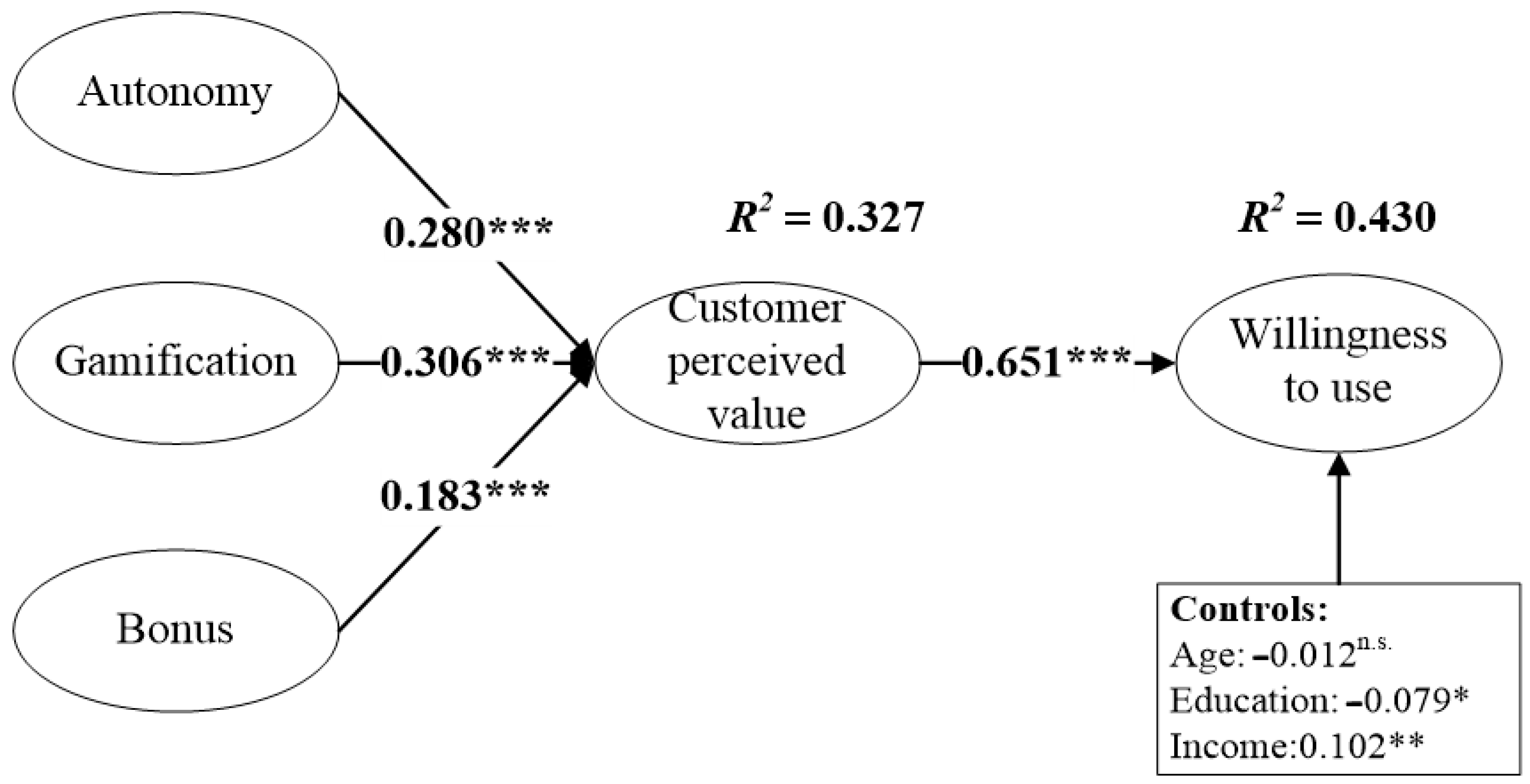

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Contribution

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Haenn, N. The Middle-Class Conservationist: Social Dramas, Blurred Identity Boundaries, and Their Environmental Consequences in Mexican Conservation. Curr. Anthropol. 2016, 57, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obuobi, B.; Tang, D.; Awuah, F.; Nketiah, E.; Adu-Gyamfi, G. Utilizing Ant Forest Technology to Foster Sustainable Behaviors: A Novel Approach towards Environmental Conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M.; Kabanshi, A.; Langeborg, L.; Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Eriksson, O.; Sörqvist, P. Deceptive Sustainability: Cognitive Bias in People’s Judgment of the Benefits of CO2 Emission Cuts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Xiong, X.; Ren, X. A Bibliometric Analysis of Consumer Neuroscience towards Sustainable Consumption. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Mi, J. A Research about Consumer Usage Intention to Green Finance Products: Taking Alipay Ant Forest as the Example. WHICEB 2018 Proceedings, 19. 2018. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/whiceb2018/19 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Zhang, B.; Hu, X.; Gu, M. Promote Pro-Environmental Behaviour through Social Media: An Empirical Study Based on Ant Forest. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 137, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ma, Y.; Addo, P.C.; Liao, M.; Fang, J. The Role of Platform Quality on Consumer Purchase Intention in the Context of Cross-Border E-Commerce: The Evidence from Africa. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörry, S.; Schulz, C. Green Financing, Interrupted. Potential Directions for Sustainable Finance in Luxembourg. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Shen, X.; Yang, L.; Kao, P. Motivation to Participate in Ant Forest. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UN Environment Programme. China’s Ant Forest Project Won the UN Earth Champion Award. 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/zh-hans/xinwenyuziyuan/xinwengao/zhongguomayisenlinxiangmuronghuolianheguodeqiuweishijiang (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Wang, K.-H.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Jiang, C.-F.; Li, Z.-Z. Does Green Finance Inspire Sustainable Development? Evidence from a Global Perspective. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 75, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Feng, Y.; Sun, J.; Yan, J. Motivation Analysis of Online Green Users: Evidence from Chinese “Ant Forest”. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. FinTech and Green Finance: The Case of Ant Forest in China. In Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, G. User Continuance of a Green Behavior Mobile Application in China: An Empirical Study of Ant Forest. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J. Environmental Finance: Linking Two World. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Financial Innovations for Biodiversity Bratislava, Bratislava, Slovakia, 1–3 May 1998; Volume 1, pp. 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, J.J.; Jeucken, M.; Klinkers, L.; Touche, D. Sustainable Banking: The Greening of Finance; Greenleaf Pub.: Sheffield, UK, 2001; ISBN 9781909493186. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, N. Definition of Green Finance; German Institute of Development and Sustainability: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.H.; Tao, J.Y. Bond Financing for Renewable Energy in Asia. Energy Policy 2016, 95, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, S.; Ajmi, A.N.; Mokni, K. Relationship between Green Bonds and Financial and Environmental Variables: A Novel Time-Varying Causality. Energy Econ. 2020, 92, 104941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Dong, K.; Dong, X. How Green Growth Affects Carbon Emissions in China: The Role of Green Finance. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 36, 2090–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. The Interactive Impact of Green Finance, ESG Performance, and Carbon Neutrality. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Datta, R.; Mohajan, H. Green Finance Is Essential for Economic Development and Sustainability. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/51169/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Muganyi, T.; Yan, L.; Sun, H. Green Finance, Fintech and Environmental Protection: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2021, 7, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaleno, M.; Dogan, E.; Taskin, D. A Step Forward on Sustainability: The Nexus of Environmental Responsibility, Green Technology, Clean Energy and Green Finance. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z. Public Participation Behavior in “Internet plus Tree-Planting” in China: A Comparison between Government-Led and Enterprise-Led Modes. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 433, 139681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Peng, Z. Research on Sustainable Development—Take “Ant Forest” for Example. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 242, 052031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L. Playing Ant Forest to Promote Online Green Behavior: A New Perspective on Uses and Gratifications. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ali, F.; Waheed, A.; Nawaz, S. You Plant a Virtual Tree, We’ll Plant a Real Tree: Understanding Users’ Adoption of the Ant Forest Mobile Gaming Application from a Behavioral Reasoning Theory Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Tu, S. An Empirical Study on Corporate ESG Behavior and Employee Satisfaction: A Moderating Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabio, R.A.; Croce, A. The Role of Peace Attitudes on Sustainable Behaviors: An Exploratory Study. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Walker, T. How to Regain Green Consumer Trust after Greenwashing: Experimental Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-13324-007 (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In Perspectives on Motivation; Dienstbier, R., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1991; Volume 38, pp. 237–288. [Google Scholar]

- Donato, P.; Link, M.W. The gamification of marketing research. Mark. News 2013, 47, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp, K. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781118096345. [Google Scholar]

- Werbach, K.; Hunter, D. For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781613630235. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göhler, G.-F.; Hattke, J.; Göbel, M. The Mediating Role of Prosocial Motivation in the Context of Knowledge Sharing and Self-Determination Theory. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A Meta-Analytic Review of Experiments Examining the Effects of Extrinsic Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 9780898628432. [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, N. “The (Short) Prehistory of “Gamification”, Funding Startups (& Other Impossibilities) Blog. 9 August 2011. Available online: http://nanodome.wordpress.com/2011/08/09/the-short-prehistory-of-gamification/ (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Jakubowski, M. Gamification in Business and Education—Project of Gamified Course for University Students. Dev. Bus. Simul. Exp. Learn. 2014, 41, 339–342. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments–MindTrek ’11, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; Volume 11, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Saenz-de-Navarrete, J.; de-Marcos, L.; Fernández-Sanz, L.; Pagés, C.; Martínez-Herráiz, J.-J. Gamifying Learning Experiences: Practical Implications and Outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, J.V.; Schipper, J. Motivational Effects and Age Differences of Gamification in Product Advertising. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.; Scheiner, C.; Robra-Bissantz, S. Gamification of Online Idea Competitions: Insights from an Explorative Case; Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Informatik: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, L. Having Fun While Receiving Rewards?: Exploration of Gamification in Loyalty Programs for Consumer Loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, S.; Rana, S.; Drave, V.A. Factors Driving Consumer Engagement and Intentions with Gamification of Mobile Apps. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2020, 18, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathian, M.; Sharifi, H.; Solat, F. Investigating the Effect of Gamification Mechanics on Customer Loyalty in Online Stores. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Sansone, C. Rewarding Competence. In Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Y.; Jeon, H. Effects of Loyalty Programs on Value Perception, Program Loyalty, and Brand Loyalty. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.-L.; Chen, C.-C. What Drives In-App Purchase Intention for Mobile Games? An Examination of Perceived Values and Loyalty. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 16, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R. A Theory of Fun for Game Design; Paraglyph Press: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2005; ISBN 9781932111972. [Google Scholar]

- Hallford, N.; Hallford, J. Swords and Circuitry: A Designer’s Guide to Computer Role-Playing Games; Premier Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2001; pp. 1–544. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, G. Anticipation and the Valuation of Delayed Consumption. Econ. J. 1987, 97, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. The Process of Moralization. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 10, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Sun, C.-T. Game-Assisted Social Activism: Game Literacy in Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Movement. Games Cult. 2022, 17, 155541202110618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; James, J.D.; Kim, Y.K. A Model of the Relationship among Sport Consumer Motives, Spectator Commitment, and Behavioral Intentions. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, D.J.; Wachter, K. A Study of Mobile User Engagement (MoEN): Engagement Motivations, Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Continued Engagement Intention. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Shute, V.; Kuba, R.; Dai, C.-P.; Yang, X.; Smith, G.; Alonso Fernández, C. The Use and Effects of Incentive Systems on Learning and Performance in Educational Games. Comput. Educ. 2021, 165, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, D.J.; Woodruff, R.B.; Gardial, S.F. Customer Value Change in Industrial Marketing Relationships: A Call for New Strategies and Research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1997, 26, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, J. Customer-Perceived Value in Industrial Contexts. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2000, 15, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaga, W.; Chacour, S. Measuring Customer-Perceived Value in Business Markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, F.N.; Suzianti, A. Driving Factors Analysis of Mobile Game In-App Purchase Intention in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 3rd Asia Pacific Conference on Research in Industrial and Systems Engineering, Depok, Indonesia, 16–17 June 2020; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D. Information Exchanges Associated with Internet Travel Marketplaces. Online Inf. Rev. 2004, 28, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Carr, C.L.; Peck, J.; Carson, S. Hedonic and Utilitarian Motivations for Online Retail Shopping Behavior. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Lu, H.-P. Why Do People Play On-Line Games? An Extended TAM with Social Influences and Flow Experience. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-C.; Tsai, T.-R. What Drives People to Continue to Play Online Games? An Extension of Technology Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2010, 26, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemes, M.D.; Gan, C.; Zhang, J. An Empirical Analysis of Online Shopping Adoption in Beijing, China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Rossmann, A.; tom Dieck, M.C. An Adoption Framework for Mobile Augmented Reality Games: The Case of Pokémon Go. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Payment and Clearing Association. Age Distribution of China Mobile Payment Users. 2022. Available online: https://www.pcac.org.cn/eportal/ui?pageId=598168&articleKey=616552&columnId=595052 (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- García Ochoa, G.; McDonald, S.; Monk, N. Embedding Cultural Literacy in Higher Education: A New Approach. Intercult. Educ. 2016, 27, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, C.; Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C. A Bibliometric-Qualitative Literature Review of Green Finance Gap and Future Research Directions. Clim. Dev. 2022, 15, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekmahmud, M.; Naz, F.; Ramkissoon, H.; Fekete-Farkas, M. Transforming Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Green Products: Role of Social Media. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 185, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Green Energy | Tree Name (Latin Name and Chinese Name) |

|---|---|

| 16,930 g | Caragana korshinskii (Kom.) and Ningtiao |

| 17,900 g | Haloxylon ammodendron (C. A. Mey.) Bunge. and Suosuo |

| 21,310 g | Hedysarum mongolicum (Turez.) and Yangchai |

| 21,310 g | Hedysarum scoparium (Fisch. & C. A. Mey.) B.Fedtsch. and Huabang |

| 38,570 g | Armeniaca sibirica (L.) Lam. and Shanxing |

| 96,000 g | Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco and Cebai |

| 114,000 g | Pinus tabulaeformis (Carr.) and Yousong |

| 146,210 g | Pinus sylvestris L. var. mongholica (Litv.) and Zhangzisong |

| 198,000 g | Picea asperata (Mast.) and Yunshan |

| Research Variable | Question (Strongly Disagree (1)/Strongly Agree (7)) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | (Aut_1) Ant Forest provides many ways and methods to complete the game goals, I can choose freely. | [27,29] |

| (Aut_2) Ant Forest makes it possible for me to make personal decisions in its activities. | ||

| (Aut_3) Through the ant forest rankings, I can show my public welfare achievements. | ||

| (Aut_4) If possible, I will interact more with my friends in Ant Forest. | ||

| Gamification | (Gam_1) I think Ant Forest’s player leaderboard design is interesting. | [13,14] |

| (Gam_2) Through the ant forest rankings, I can show my public welfare achievements. | ||

| (Gam_3) I think the game of Ant Forest is very interesting. | ||

| (Gam_4) Compared with other green financial platforms, the gamification method of Ant Forest is more attractive to me. | ||

| Bonus | (Bon_1) I try to get more medals, environmental certificates as my activity reward. | [28] |

| (Bon_2) I am trying to get more green energy as my activity reward. | ||

| (Bon_3) I’m trying to have a higher leaderboard rank as a reward for my event. | ||

| (Bon_4) The Rewards of Ant Forest can motivate me to use it for a long time. | ||

| CPV | (CPV_1) I think the concept that Alipay wants to convey is the core of the Ant Forest game. | [29,30] |

| (CPV_2) I think Alipay’s image is related to the theme of Ant Forest. | ||

| (CPV_3) I can feel the concept that Alipay wants to convey from Ant Forest. | ||

| (CPV_4) Overall, I am satisfied with the design of Ant Forest. | ||

| Willingness to use | (WTU_1) In the future, I would like to continue to participate in the public welfare activities of Ant Forest. | [21,28] |

| (WTU_2) I think that by using Ant Forest increased my willingness to use Alipay. | ||

| (WTU_3) My plan is to keep playing Ant Forest and not choose other similar apps. | ||

| (WTU_4) I would like to introduce Ant Forest to my relatives and friends. |

| Items | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | <20 | 84 | 13.9 |

| 20–29 | 243 | 40.1 | |

| 30–40 | 202 | 33.3 | |

| >40 | 77 | 12.7 | |

| Education | Middle school or below | 12 | 2.0 |

| High school | 175 | 28.9 | |

| Bachelor | 394 | 65.0 | |

| Postgraduate or above | 25 | 4.1 | |

| Monthly income (CNY) | <3000 | 20 | 3.3 |

| 3001–5000 | 274 | 45.2 | |

| 5001–8000 | 219 | 36.1 | |

| >8000 | 93 | 15.3 | |

| Usage experience | Yes | 586 | 96.7 |

| No | 20 | 3.3 | |

| Usage frequency (weekly) | 0 | 20 | 3.3 |

| 1–2 | 274 | 45.2 | |

| 3–4 | 219 | 36.1 | |

| >5 | 93 | 15.3 | |

| Gender | Male | 291 | 48.0 |

| Female | 315 | 52.0 |

| AUT | GAM | BON | CPV | WTU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUT | 0.826 a | ||||

| GAM | 0.278 b | 0.813 | |||

| BON | 0.320 | 0.357 | 0.799 | ||

| CPV | 0.378 | 0.413 | 0.337 | 0.785 | |

| WTU | 0.576 | 0.524 | 0.544 | 0.600 | 0.776 |

| Construct | Item | Mean | SD | λ | Alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy (AUT) | AUT1 | 4.868 | 1.512 | 0.817 | 0.895 | 0.682 | 0.895 |

| AUT2 | 4.871 | 1.484 | 0.845 | ||||

| AUT3 | 4.883 | 1.483 | 0.821 | ||||

| AUT4 | 4.870 | 1.501 | 0.819 | ||||

| Gamification (GAM) | GAM1 | 5.149 | 1.310 | 0.811 | 0.886 | 0.661 | 0.886 |

| GAM2 | 5.157 | 1.311 | 0.796 | ||||

| GAM3 | 5.150 | 1.314 | 0.821 | ||||

| GAM4 | 5.158 | 1.280 | 0.823 | ||||

| Bonus (BON) | BON1 | 5.335 | 1.250 | 0.807 | 0.876 | 0.639 | 0.876 |

| BON2 | 5.340 | 1.241 | 0.770 | ||||

| BON3 | 5.330 | 1.268 | 0.798 | ||||

| BON4 | 5.333 | 1.281 | 0.821 | ||||

| Customer-perceived value (CPV) | CPV1 | 4.762 | 1.569 | 0.773 | 0.865 | 0.616 | 0.865 |

| CPV2 | 4.744 | 1.579 | 0.785 | ||||

| CPV3 | 4.766 | 1.573 | 0.773 | ||||

| CPV4 | 4.746 | 1.580 | 0.807 | ||||

| Willingness to use (WTU) | WTU1 | 4.995 | 1.308 | 0.775 | 0.858 | 0.602 | 0.858 |

| WTU2 | 4.997 | 1.256 | 0.765 | ||||

| WTU3 | 4.997 | 1.273 | 0.789 | ||||

| WTU4 | 4.977 | 1.296 | 0.774 |

| Indirect Effect | Boot SE a | BLLCI b | BULCI c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUT to WTU | 0.182 | 0.038 *** | 0.117 | 0.269 |

| GAM to WTU | 0.199 | 0.037 *** | 0.133 | 0.280 |

| BON to WTU | 0.119 | 0.036 ** | 0.053 | 0.196 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, X.; Gong, C.; Su, Z.; Nie, Y.; Kim, W. Consumers’ Behavioral Willingness to Use Green Financial Products: An Empirical Study within a Theoretical Framework. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080634

Xie X, Gong C, Su Z, Nie Y, Kim W. Consumers’ Behavioral Willingness to Use Green Financial Products: An Empirical Study within a Theoretical Framework. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):634. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080634

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Xiangwei, Chunxi Gong, Zhenqing Su, Yufei Nie, and Woohyoung Kim. 2024. "Consumers’ Behavioral Willingness to Use Green Financial Products: An Empirical Study within a Theoretical Framework" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080634

APA StyleXie, X., Gong, C., Su, Z., Nie, Y., & Kim, W. (2024). Consumers’ Behavioral Willingness to Use Green Financial Products: An Empirical Study within a Theoretical Framework. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080634