A Caregiver Perspective for Partners of PTSD Survivors: Understanding the Experiences of Partners

Abstract

:1. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Romantic Partners

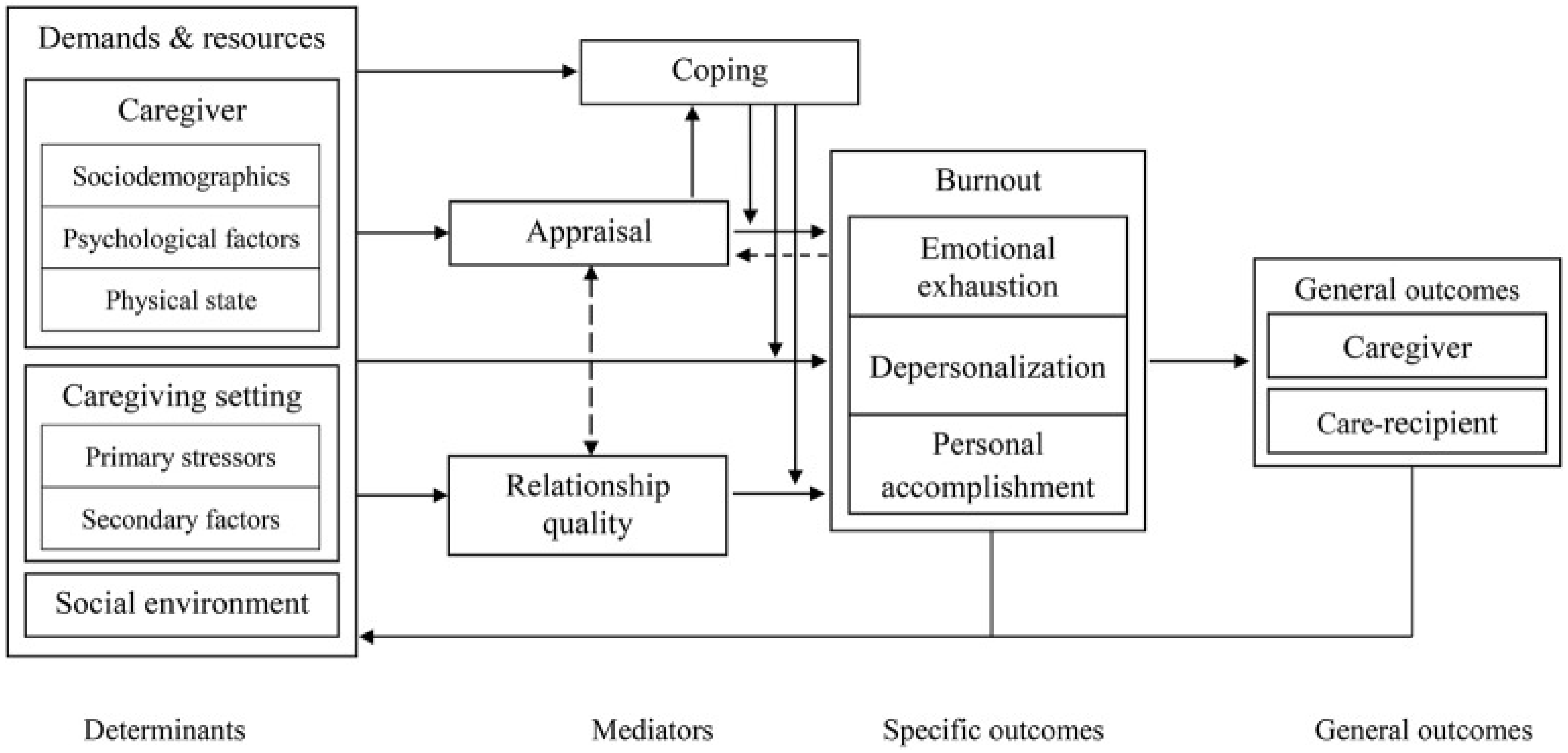

2. Informal Caregiving Integrative Model

2.1. Determinants of Caregiver Burnout

2.2. Mediators of Caregiver Burnout

2.3. Caregiver Burnout

2.4. General Outcomes

3. Future Research Directions

4. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, J.E.; Engh, R.; Hasbun, A.; Holzer, J. Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the relationship quality and psychological distress of intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chung, M.C.; Wang, N.; Yu, X.; Kenardy, J. Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 85, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkley, E.L.; Eckhardt, C.I.; Dykstra, R.E. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence, and relationship functioning: A meta-analytic review. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMauro, J.; Renshaw, K.D. PTSD and relationship satisfaction in female survivors of sexual assault. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, N.J.; Dixon, L.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Valentine, S.E.; Bosley, H.G.; Gerber, M.W.; Marques, L. PTSD and romantic relationship satisfaction: Cluster-and symptom-level analyses. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renshaw, K.D.; Allen, E.S.; Fredman, S.J.; Giff, S.T.; Kern, C. Partners’ motivations for accommodating posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in service members: The reasons for accommodation of PTSD scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 71, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, A.; Pukay-Martin, N.D.; Wagner, A.C.; Fredman, S.J.; Monson, C.M. Cognitive–behavioral conjoint therapy for PTSD improves various PTSD symptoms and trauma-related cognitions: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manguno-Mire, G.; Sautter, F.; Lyons, J.; Myers, L.; Perry, D.; Sherman, M.; Glynn, S.; Sullivan, G. Psychological distress and burden among female partners of combat veterans with PTSD. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.B.; Renshaw, K.D. Posttraumatic stress disorder and relationship functioning: A comprehensive review and organizational framework. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 65, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, S.; Garcés, J.; Ródenas, F.; Sanjosé, V. The informal caregiver’s burden of dependent people: Theory and empirical review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, P.S.; Beckham, J.C.; Bosworth, H.B. Caregiver burden and psychological distress in partners of veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma. Stress 2002, 15, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Informal caregiver burnout? Development of a theoretical framework to understand the impact of caregiving. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 11, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Biscardi, M.; Astell, A.; Nalder, E.; Cameron, J.I.; Mihailidis, A.; Colantonio, A. Sex and gender differences in caregiving burden experienced by family caregivers of persons with dementia: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.H.; Lyons, K.S.; Stewart, B.J.; Archbold, P.G.; Scobee, R. Does age make a difference in caregiver strain? Comparison of young versus older caregivers in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokurcan, A.; Özpolat, A.G.Y.; Göğüş, A.K. Burnout in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 45, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindt, N.; van Berkel, J.; Mulder, B.C. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopp, K.; Wrape, E.R.; McInnis, R.; Khalifian, C.E.; Rashkovsky, K.; Glynn, S.M.; Morland, L.A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and relationship functioning: Examining gender differences in treatment-seeking veteran couples. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 35, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renshaw, K.D.; Rodebaugh, T.L.; Rodrigues, C.S. Psychological and marital distress in spouses of Vietnam veterans: Importance of spouses’ perceptions. J. Anxiety Disord. 2010, 24, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapin, M. Family resilience and the fortunes of war. Soc. Work Health Care 2011, 50, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beks, T. Walking on Eggshells: The Lived Experience of Partners of Veterans with PTSD. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, S.; Nelson Goff, B.S. A qualitative analysis of military couples with high and low trauma symptoms and relationship distress levels. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2014, 13, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddour, L.; Kishita, N. Anxiety in informal dementia carers: A meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2020, 33, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, M.; Lee, Y.; Choi, S.H.; Moon, S.Y.; Seo, S.W.; Park, K.W.; Ku, B.D.; Han, H.J.; Park, K.H.; et al. Influence of personality on depression, burden, and health-related quality of life in family caregivers of persons with dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murfield, J.; Moyle, W.; O’Donovan, A.; Ware, R.S. The role of self-compassion, dispositional mindfulness, and emotion regulation in the psychological health of family carers of older adults. Clin. Gerontol. 2020, 47, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, A.; Lai, M.K.; Lau, K.M.; Pan, P.C.; Lam, L.; Thompson, L.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. Social support and well-being in dementia family caregivers: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Aging Ment. Health 2009, 13, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuijpers, P.; Stam, H. Burnout among relatives of psychiatric patients attending psychoeducational support groups. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombestein, H.; Norheim, A.; Lunde Husebø, A.M. Understanding informal caregivers’ motivation from the perspective of self-determination theory: An integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 34, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, M.M.; Corry, N.H.; Qian, M.; Li, M.; McMaster, H.S.; Fairbank, J.A.; Marmar, C.R. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in United States military spouses: The millennium cohort family study. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, H.B. A Narrative Study of the Spouses of Traumatized Canadian Soldiers. Doctoral Dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw, K.D.; Allen, E.S.; Carter, S.P.; Markman, H.J.; Stanley, S.M. Partners’ attributions for service members’ symptoms of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav. Ther. 2014, 45, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, A.; Valente, L.; Ulstein, I.; Engelhardt, E.; Laks, J.; Engedal, K. Burnout in familial caregivers of patients with dementia. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2012, 34, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, F.M.; Cumming, R.G.; Brnabic, A.J.; Cousins, M.J. Caregiving in the presence of chronic pain. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koic, E.; Muzinic-Masle, L.; Franciskovic, T.; Vondracek, S.; Djordjevic, V.; Per-Koznjak, J.; Prpic, J. Chronic pain in the wives of the Croatian war veterans treated for PTSD. Eur. Psychiatry 2002, 17, 201s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkzwager, A.J.; Bramsen, I.; Adèr, H.; van der Ploeg, H.M. Secondary traumatization in partners and parents of Dutch peacekeeping soldiers. J. Fam. Psychol. 2005, 19, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, R.J.V.; Gonyea, J.G.; Hooyman, N.R. Caregiving and the experience of subjective and objective burden. Fam. Relat. 1985, 34, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.Y.; Wu, H.S.; Hsiao, C.Y. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Does informal caregiving lead to parental burnout? Comparing parents having (or not) children with mental and physical issues. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, N.; Dellmann-Jenkins, M.; Smith, G.C.; Coeling, H.; Johnson, R.J. The emotional needs of care recipients and the psychological well-being of informal caregivers: Implications for home care clinicians. Home Healthc. Now 2008, 26, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, R.; Solomon, Z.; Bleich, A. Emotional distress and marital adjustment of caregivers: Contribution of level of impairment and appraised burden. Anxiety Stress Coping 2005, 18, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, M.S.; Lund, D.A.; Wright, S.D. Exploring the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI): Further evidence for a multidimensional view of burden. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1996, 43, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, C.T.; Watkins, L.E.; Stafford, J.; Street, A.E.; Monson, C.M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otis-Green, S.; Juarez, G. Enhancing the social well-being of family caregivers. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 28, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, K.; Kabayama, M.; Ito, M. Experiences of “endless” caregiving of impaired elderly at home by family caregivers: A qualitative study. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, M.D.; Zanotti, D.K.; Jones, D.E. Key elements in couples therapy with veterans with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005, 36, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Z.; Dekel, R.; Zerach, G. The relationships between posttraumatic stress symptom clusters and marital intimacy among war veterans. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.D.; Perlick, D.A.; Straits-Tröster, K. Adapting the multifamily group model for treating veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Serv. 2012, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, E.P.; Sherman, M.D.; Han, X.; Owen Jr, R.R. Outcomes of participation in the REACH multifamily group program for veterans with PTSD and their families. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2013, 44, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharr, J.R.; Dodge Francis, C.; Terry, C.; Clark, M.C. Culture, caregiving, and health: Exploring the influence of culture on family caregiver experiences. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2014, 2014, 689826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andruske, C.L.; O’Connor, D. Family care across diverse cultures: Re-envisioning using a transnational lens. J. Aging Stud. 2020, 55, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, B.; Buntinx, F.; DeLepeleire, J. Supporting the dementia family caregiver: The effect of home care intervention on general well-being. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, K.F.D.; Boery, R.N.S.D.O.; Pereira, R.; Pedreira, L.C.; Vilela, A.B.A.; Santos, V.C.; Rosa, D.D.O.S. Association between social support and quality of life of relative caregivers of elderly dependents. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2015, 20, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, K.; Azampoor-Afshar, S.; Karami, G.; Mokhtari, A. The association of veterans’ PTSD with secondary trauma stress among veterans’ spouses. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2011, 20, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J.S.; Renshaw, K.D.; Allen, E.S.; Markman, H.J.; Stanley, S.M. Meaningfulness of service and marital satisfaction in Army couples. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowronski, S. PTSD on Relational and Sexual Functioning and Satisfaction: Evaluating the Effects of PTSD, Emotional Numbing, Moral Injury, and Caregiver Burden. Ph.D. Dissertation, Widener University, Chester, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fredman, S.J.; Vorstenbosch, V.; Wagner, A.C.; Macdonald, A.; Monson, C.M. Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Initial testing of the Significant Others’ Responses to Trauma Scale (SORTS). J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, J.J.; Allen, E.; Renshaw, K.; Bhalla, A.; Fredman, S.J. Two perspectives on accommodation of PTSD symptoms: Partners versus service members. Couple Fam. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2021, 11, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.B.; Renshaw, K.D. Daily posttraumatic stress disorder symptom accommodation and relationship functioning in military couples. Fam. Process 2019, 58, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredman, S.J.; Le, Y.; Renshaw, K.D.; Allen, E.S. Longitudinal Associations among Service Members’ PTSD Symptoms, Partner Accommodation, and Partner Distress. Behav. Ther. 2022, 53, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, P.A.; Monson, C.M.; Chard, K.M. Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD: A Comprehensive Manual; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gudat, H.; Ohnsorge, K.; Streeck, N.; Rehmann-Sutter, C. How palliative care patients’ feelings of being a burden to others can motivate a wish to die. Moral challenges in clinics and families. Bioethics 2019, 33, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuman, L.; Thompson-Hollands, J. Family accommodation in PTSD: Proposed considerations and distinctions from the established transdiagnostic literature. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 30, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, M.; Takahashi, M.; Iwamitsu, Y.; Oishi, S.; Miyaoka, H. Subjective experiences of family caregivers of patients with dementia as predictive factors of quality of life. Psychogeriatrics 2011, 11, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, S.; Rassouli, M.; Ilkhani, M.; Baghestani, A.R. Perceptions of family caregivers of cancer patients about the challenges of caregiving: A qualitative study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajiwara, K.; Nakatani, H.; Ono, M.; Miyakoshi, Y. Positive appraisal of in-home family caregivers of dementia patients as an influence on the continuation of caregiving. Psychogeriatrics 2015, 15, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, M.; Scholz, U.; Bailey, B.; Perren, S.; Hornung, R.; Martin, M. Dementia caregiving in spousal relationships: A dyadic perspective. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 13, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, D.S.; Byrne, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T. The quality of the intimate relationships of male Vietnam veterans: Problems associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma. Stress 1998, 11, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renshaw, K.D.; Caska, C.M. Relationship distress in partners of combat veterans: The role of partners’ perceptions of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behav. Ther. 2012, 43, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimesey, J. The Impact of Combat Trauma on Veterans’ Family Members: A Qualitative Study. Doctoral Dissertation, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Monson, C.M.; Fredman, S.J.; Macdonald, A.; Pukay-Martin, N.D.; Resick, P.A.; Schnurr, P.P. Effect of cognitive-behavioral couple therapy for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012, 308, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, S.J.; Beck, J.G.; Shnaider, P.; Le, Y.; Pukay-Martin, N.D.; Pentel, K.Z.; Monson, C.M.; Simon, N.M.; Marques, L. Longitudinal associations between PTSD symptoms and dyadic conflict communication following a severe motor vehicle accident. Behav. Ther. 2017, 48, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.B.; Renshaw, K.D. PTSD symptoms, disclosure, and relationship distress: Explorations of mediation and associations over time. J. Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pukay-Martin, N.D.; Fredman, S.J.; Martin, C.E.; Le, Y.; Haney, A.; Sullivan, C.; Monson, C.M.; Chard, K.M. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral conjoint therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in a US Veterans Affairs PTSD clinic. J. Trauma. Stress 2022, 35, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMotte, A.D.; Taft, C.T.; Reardon, A.F.; Miller, M.W. Veterans’ PTSD symptoms and their partners’ desired changes in key relationship domains. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2015, 7, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, D.S. Traumatized relationships: Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, fear of intimacy, and marital adjustment in dual trauma couples. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2014, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosebrock, L.; Carroll, R. Sexual function in female veterans: A review. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2017, 43, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigras, N.; Godbout, N.; Briere, J. Child sexual abuse, sexual anxiety, and sexual satisfaction: The role of self-capacities. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2015, 24, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMauro, J.; Renshaw, K.D. Trauma-related disclosure in sexual assault survivors’ intimate relationships: Associations with PTSD, shame, and partners’ responses. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP1986-2004NP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Montigny Gauthier, L.; Vaillancourt-Morel, M.P.; Rellini, A.; Godbout, N.; Charbonneau-Lefebvre, V.; Desjardins, F.; Bergeron, S. The risk of telling: A dyadic perspective on romantic partners’ responses to child sexual abuse disclosure and their associations with sexual and relationship satisfaction. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2019, 45, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.B.; Renshaw, K.D. Distress in spouses of Vietnam veterans: Associations with communication about deployment experiences. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.H.; Shuster, G.; Lobo, M.L. The family caregiver experience–examining the positive and negative aspects of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue as caregiving outcomes. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klarić, M.; Frančišković, T.; Pernar, M.; Nemčić Moro, I.; Milićević, R.; Černi Obrdalj, E.; Salčin Satriano, A. Caregiver burden and burnout in partners of war veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Coll. Antropol. 2010, 34, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whealin, J.M.; Yoneda, A.C.; Nelson, D.; Hilmes, T.S.; Kawasaki, M.M.; Yan, O.H. A culturally adapted family intervention for rural Pacific Island veterans with PTSD. Psychol. Serv. 2017, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, R.; Goldblatt, H.; Keidar, M.; Solomon, Z.; Polliack, M. Being a wife of a veteran with posttraumatic stress disorder. Fam. Relat. 2005, 54, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. A harmful care: The association of informal caregiver burnout with depression, subjective health, and violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP9738–NP9762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, C.; Glass, N.E. Interpersonal Violence: A Review of Elder Abuse. Curr. Trauma Rep. 2020, 6, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caska, C.M.; Smith, T.W.; Renshaw, K.D.; Allen, S.N.; Uchino, B.N.; Birmingham, W.; Carlisle, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and responses to couple conflict: Implications for cardiovascular risk. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloney, L.J. Post traumatic stresses on women partners of Vietnam veterans. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work 1988, 58, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C.R.; Andrews, B.; Valentine, J.D. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cannon, C.J.; Gray, M.J. A Caregiver Perspective for Partners of PTSD Survivors: Understanding the Experiences of Partners. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080644

Cannon CJ, Gray MJ. A Caregiver Perspective for Partners of PTSD Survivors: Understanding the Experiences of Partners. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080644

Chicago/Turabian StyleCannon, Christopher J., and Matt J. Gray. 2024. "A Caregiver Perspective for Partners of PTSD Survivors: Understanding the Experiences of Partners" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 644. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080644