The Relationships of Self-Sustained English Learning, Language Mindset, Intercultural Communicative Skills, and Positive L2 Self: A Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Sustained Learning

2.2. Intercultural Communicative Skills

2.3. Language Mindset

2.4. Positive L2 Self

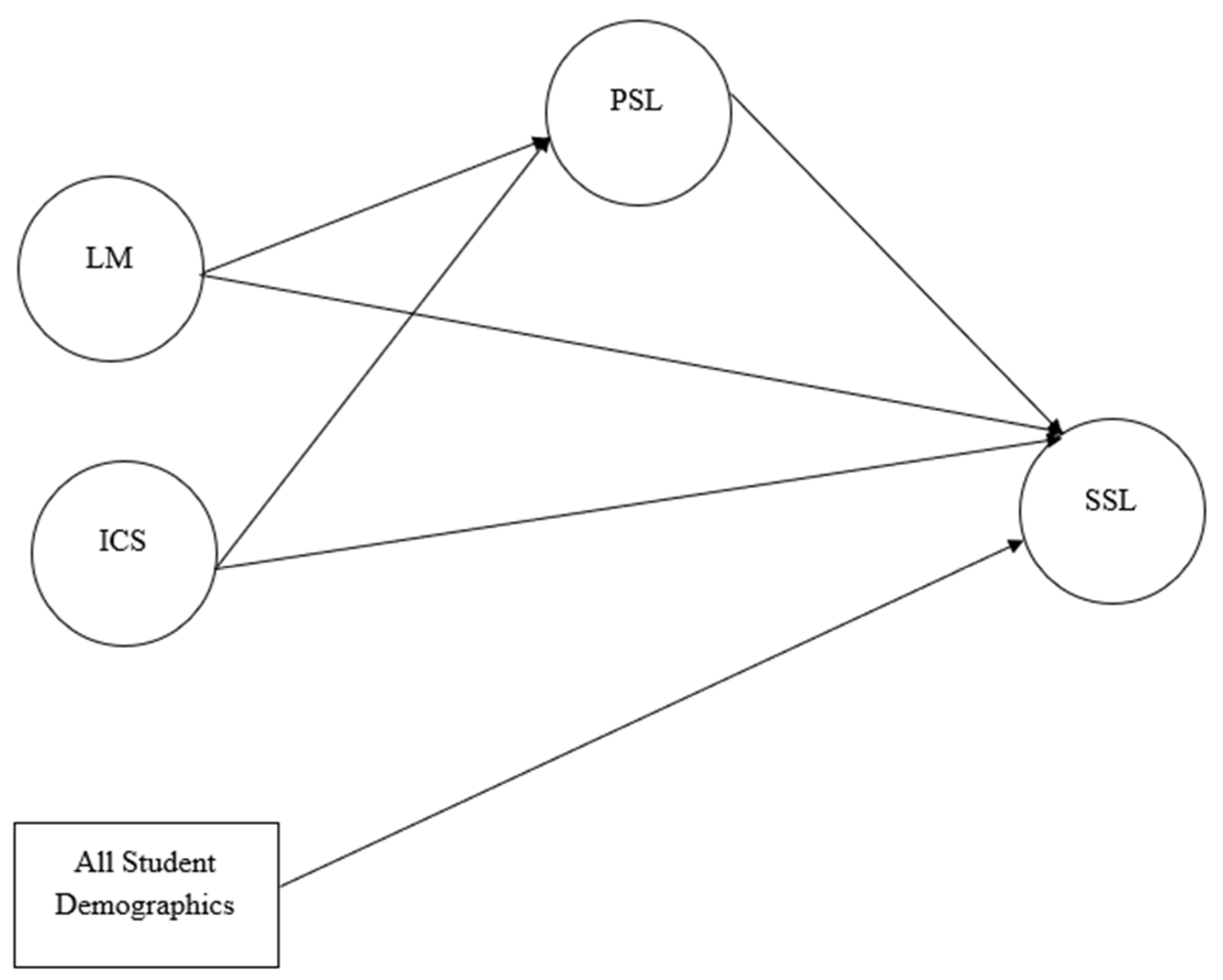

3. The Current Study

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Language Mindset

4.2.2. Intercultural Communicative Skills

4.2.3. Positive L2 Self

4.2.4. Self-Sustained English Learning

4.2.5. Demographic Background

4.3. Procedure

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

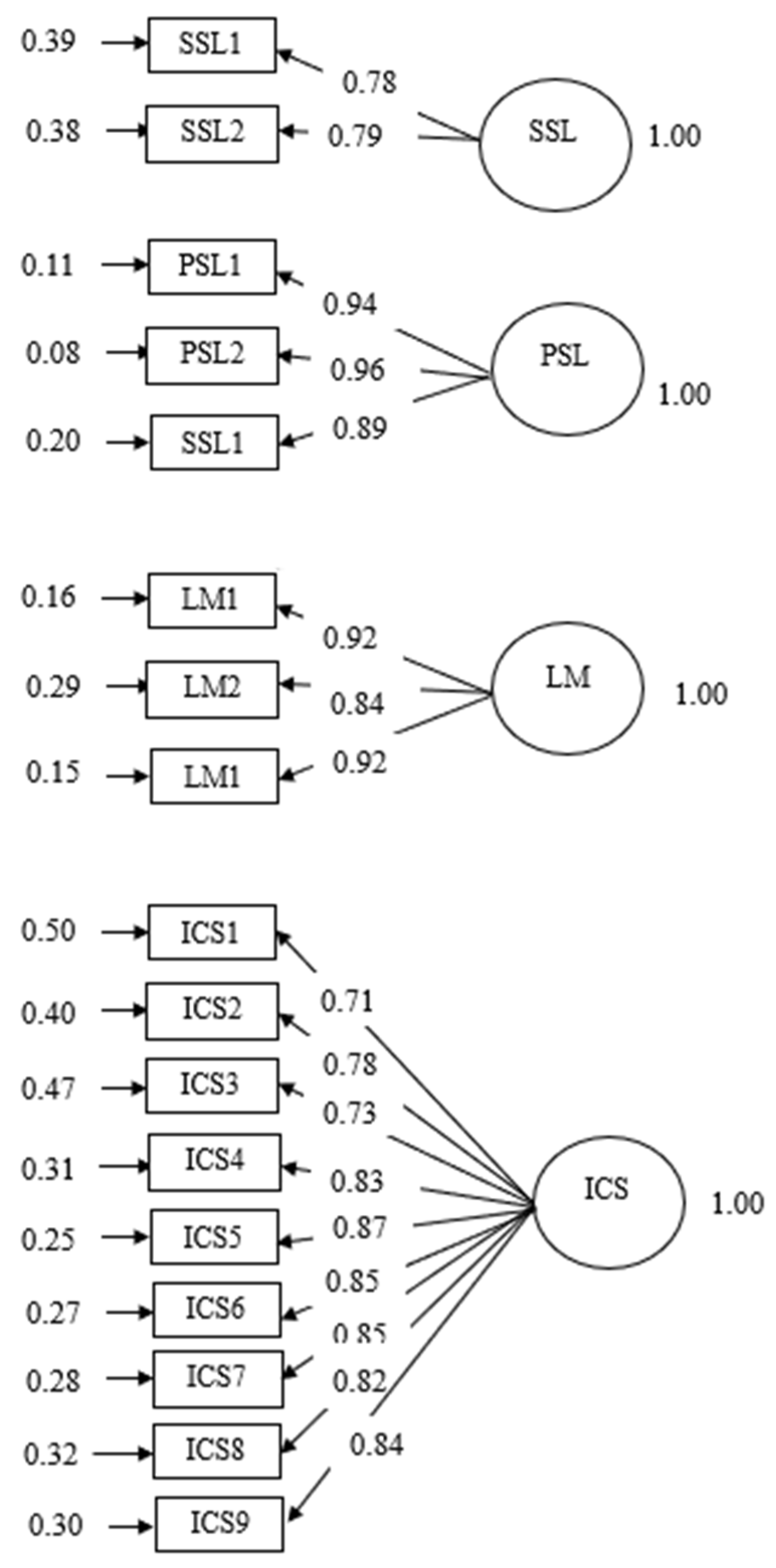

5.2. CFA

5.3. SEM

6. Discussion

Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crystal, D. English as a Global Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. Global Englishes: A Resource Book for Students; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R.; Su, J. The statistics of English in China: An analysis of the best available data from government sources. Engl. Today 2012, 28, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G. English language education in China: Policies, progress, and problems. Lang. Policy 2005, 4, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B. Understanding primary school students’ use of self-regulated writing strategies through think-aloud protocols. System 2018, 78, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, J. The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Lang. Teach. Res. 2023, 27, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C. Tracing trajectories of young learners: Ten years of school English learning. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 2017, 37, 168–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. Chinese students’ motivation to learn English at the tertiary level. Asian EFL J. 2007, 9, 126–146. [Google Scholar]

- Su, D. A Study of English Learning Strategies and Styles of Chinese University Students in Relation to Their Cultural Beliefs and Beliefs about Learning English; University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G.; Chang, Y.; Xu, Y. Chinese college students’ self regulated learning strategies and self-efficacy beliefs in learning English as a foreign language. J. Educ. Res. 2012, 22, 103–135. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Liu, C.; Fang, F.; Elyas, T. “How is my English?”: Chinese university students’ attitudes toward China English and their identity construction. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211038271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Promoting self-sustained learning in higher education: The ISEE framework. Teach. High. Educ. J. 2015, 20, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, B. Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective. Hum. Dev. 2006, 49, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, B.; Martin, C.K.; Roberts, E. Sparking self-sustained learning: Report on a design experiment to build technological fluency and bridge divides. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2007, 17, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, R.; Bown, J.; Dewey, D.; Belnap, L.; Steffen, P. 12 project perseverance: Helping students become self-regulating learners. In Positive Psychology in SLA; MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., Mercer, S., Eds.; Blue Ridge Summit; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checketts, H.B. Guiding Language Students to Self-Sustained Learning. Unpublished Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.D. Teaching by Principles: An Interactive Approach to Language Pedagogy, 2nd ed.; San Francisco State University: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 51, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S.; Fredricks, J.A.; Simpkins, S.; Roeser, R.W.; Schiefele, U. Development of achievement motivation and engagement. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, 7th ed.; Lerner, R., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 657–700. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. The relationship of self-concepts to changes in cultural diversity awareness: Implications for urban teacher educators. Urban. Rev. 2004, 36, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N.; Rezazadeh, M.; Karimi, M.; Lou, N.M. Why do growth mindsets make you feel better about learning and yourselves? The mediating role of adaptability. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2022, 16, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette, J.L.; Pollack, J.M.; Forsyth, R.B.; Hoyt, C.L.; Babij, A.D.; Thomas, F.N.; Coy, A.E. A growth mindset intervention: Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial self-efficacy and career development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 878–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Yeager, D.S. Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, N.M.; Noels, K.A. Breaking the vicious cycle of language anxiety: Growth language mindsets improve lower-competence ESL students’ intercultural interactions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, R.G.; Lehman, D.R. Learning considered within a cultural context: Confucian and Socratic approaches. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Rao, N. Classroom goal structures: Observations from urban and rural high school classes in China. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1211–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, F.; Leite, A. Adolescents’ self-concept short scale: A version of PHCSCS. Procedia Soc. 2016, 217, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, U.; Möller, J. Self-Concept: Determinants and consequences of academic Self-Concept in school contexts. In Plenum Series on Human Exceptionality; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, J. Positive Psychology and Second Language Motivation: Empirically Validating A Model Of Positive L2 Self. Doctoral Dissertation, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, M. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lapkin, S.; Swain, M.; Smith, M. Reformulation and the learning of French pronominal verbs in a Canadian French immersion context. Mod. Lang. J. 2002, 86, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T. Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. Mod. Lang. J. 2002, 86, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T.; Zenuk-Nishide, L.; Shimizu, K. The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second language communication. Lang. Learn. 2004, 54, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Communicative language teaching in China: Progress and resistance. TESOL Q. 2001, 35, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, M.; Norton, B. Revisiting English as medium of instruction in rural African classrooms. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2014, 35, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavy, G.H.; MacIntyre, P.D.; Hariri, J. A closer look at grit and language mindset as predictors of foreign language achievement. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2021, 43, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. The Roles of Classroom Social Climate, Language Mindset, and Positive L2 Self in Predicting Chinese College Students’ Academic Resilience in English as a Foreign Language. Unpublished Dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainability: From Rio to Johannesburg, Lessons Learnt from a Decade of Commitment. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000127100 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Rowe, D. Education for a sustainable future. Science 2007, 317, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education–Re-Visioning Learning and Change, Schumacher Briefing no 6; Schumacher Society/Green Books: Dartington, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education. In Science, Society and Sustainability: Education and Empowerment for an Uncertain World; Gray, D., Colucci-Gray, L., Camino, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A. Sustainable learning in education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, B. The Cultural Nature of Human Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, K.D. Consequential transitions: A sociocultural expedition beyond transfer in education. Rev. Educ. Res. 1999, 24, 124–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S.E.; Renninger, K.A. On educating, curiosity, and interest development. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2020, 35, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biwer, F.; oude Egbrink, M.G.; Aalten, P.; de Bruin, A.B. Fostering effective learning strategies in higher education—A mixed-methods study. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2020, 9, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, R.A.; Hamm, J.M.; Parker, P.C. Promoting effective teaching and learning in higher education. High. Educ. Handb. Theory Res. 2015, 30, 245–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hativa, N. Teaching for Effective Learning in Higher Education; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Lygo-Baker, S.; Hay, D.B. Universities as centres of non-learning. High. Educ. Stud. 2008, 33, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boud, D. Reframing assessment as if learning is important. In Rethinking Assessment in Higher Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff, D.K. Identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2006, 10, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwe, K.T.; Haskollar, E. Variables impacting intercultural competence: A systematic literature review. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2020, 49, 346–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, C. Integrating intercultural and communicative objectives in the foreign language class: A proposal for the integration of two models. Lang. Learn. J. 2013, 41, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, D. On communicative competence. In Sociolinguistics; Pride, J.B., Holmes, J., Eds.; Penguin: London, UK, 1972; pp. 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.H. The ‘Dao’ and ‘Qi’ concept of intercultural competence. Lang. Teach. Res. 1998, 3, 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.X. Intercultural Communication; Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press: Shanghai, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhuang, E.P. Framework for building cross-cultural communicative competence. Foreign Lang. Wor. 2007, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.G.; Jiang, Y.M. Introduction to Applied Language and Cultural Studies; Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press: Shanghai, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.P.; Fan, W.W.; Peng, R.Z. An analysis of the assessment tools for Chinese college students’ intercultural competence. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2013, 4, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X. Assessment of intercultural communicative competence in FL education: A survey on EFL teachers’ perception and practice in China. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2016, 16, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Constructing intercultural communicative competence framework for English learners. Cross-Cult. Comm. 2014, 10, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ahnagari, S.; Zamanian, J. Intercultural communicative competence in foreign language classroom. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantini, A.E. Reconceptualizing intercultural communicative competence: A multinational perspective. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2020, 15, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, J.; Pawlak, M.; Mehraein, S.; Hosseini, H.M.; Derakhshesh, A. Foreign language enjoyment, ideal L2 self, and intercultural communicative competence as predictors of willingness to communicate among EFL learners. System 2023, 115, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.; Forouzandeh, F. Relationship between intercultural communicative competence and L2-learning motivation of Iranian EFL learners. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2013, 42, 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Duong, T.M. The effectiveness of the intercultural language communicative teaching model for EFL learners. Asian Pac. J. Sec. For. 2018, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrkoohi, A. The relationship between demotivation and intercultural communicative competence. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1531741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanat-Mutluoğlu, A. The influence of ideal L2 self, academic self-concept and intercultural communicative competence on willingness to communicate in a foreign language. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist. 2016, 2, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N.M.; Noels, K.A. Changing language mindsets: Implications for goal orientations and responses to failure in and outside the second language classroom. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N.M.; Noels, K.A. Measuring Language Mindsets and Modeling Their Relations with Goal Orientations and Emotional and Behavioral Responses in Failure Situations. Mod. Lang. J. 2017, 101, 214–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyder, A.; Weidinger, A.F.; Steinmayr, R. Only a burden for females in math? Gender and domain differences in the relation between adolescents’ fixed mindsets and motivation. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, C.J.; Ewing, J. Effects of movement, growth mindset and math talks on math anxiety. J. Multi. Aff. 2019, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. The L2 motivational self system. Motivation Lang. Identity L2 Self 2009, 36, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hoorie, A.H. The L2 motivational self system: A meta-analysis. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2018, 8, 721–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L. Tibetan CSL learners’ L2 Motivational Self System and L2 achievement. System 2021, 97, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebn-Abbasi, F.; Fattahi, N.; Noughabi, M.A.; Botes, E. The strength of self and L2 willingness to communicate: The role of L2 grit, ideal L2 self and language mindset. System 2024, 123, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughi, M.; Hejazi, S.Y.; Lou, N.M. How do growth mindsets contribute to academic engagement in L2 classes? The mediating and moderating roles of the L2 motivational self system. Soc. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 26, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, A.; Rakıcıoğlu-Söylemez, A. Language mindsets, perceived instrumentality, engagement and graded performance in English as a foreign language students. Lang. Teach. Res. 2020, 27, 1362168820958400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, A.; Patterson, M.M. The roles of class social climate, language mindset, and emotions in predicting willingness to communicate in a foreign language. System 2021, 99, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.Z.; Wu, W.P. Measuring intercultural contact and its effects on intercultural competence: A structural equation modeling approach. Int. J. Intercul. Rel. 2016, 53, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.Z.; Wu, W.P.; Fan, W.W. A comprehensive evaluation of Chinese college students’ intercultural competence. Int. J. Intercul. Rel. 2015, 47, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.Z.; Zhu, C.; Wu, W.P. Visualizing the knowledge domain of intercultural competence research: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Intercul. Rel. 2020, 74, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D.D.; Preacher, K.J.; Tormala, Z.L.; Petty, R.E. Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Soc. Personal. Psychol. 2011, 5, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Lau, R.S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation modeling. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide (1998–2012); Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.L. The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Nora, A.; Stage, F.K.; Barlow, E.A.; King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.J.; Gonzalez, O.; Miocevic, M.; MacKinnon, D.P. A note on testing mediated effects in Structural Equation Models: Reconciling past and current research on the performance of the test of joint significance. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2016, 76, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X. The role of effort in understanding academic achievements: Empirical evidence from China. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.J.; Sercombe, P.G.; Sachdev, I.; Naeb, R.; Schartner, A. Success factors for international postgraduate students’ adjustment: Exploring the roles of intercultural competence, language proficiency, social contact and social support. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2013, 3, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 850 | 68.7 |

| Male | 388 | 31.3 | |

| Grade | Undergraduate | 808 | 65.3 |

| Graduate | 430 | 34.7 | |

| Major | English Major | 940 | 75.9 |

| Non-English Major | 298 | 24.1 | |

| Length of English Learning | Less than 5 years | 89 | 7.2 |

| 5–10 Years | 757 | 61.1 | |

| 11–15 Year | 314 | 25.4 | |

| More than 15 Years | 78 | 6.3 | |

| Self-Rated English Proficiency Level | Very Poor | 43 | 3.5 |

| Poor | 211 | 17.0 | |

| Fair | 815 | 65.8 | |

| Good | 37 | 3.0 | |

| Very Good | 132 | 10.7 | |

| Going Abroad | No | 1149 | 92.8 |

| Yes | 89 | 7.2 | |

| Contact with Native Speakers | No | 704 | 56.9 |

| Once or more per year | 286 | 23.1 | |

| Once or more per month | 66 | 5.3 | |

| Once or more per week | 149 | 12.0 | |

| Once or more per day | 33 | 2.7 |

| Variables | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| LM Parcel 1—Second Language Beliefs | 3.75 | 0.79 |

| LM Parcel 2—Age Sensitivity Beliefs | 3.88 | 0.85 |

| LM Parcel 3—General Language Beliefs | 3.69 | 0.83 |

| PLS Parcel 1—Interest | 3.71 | 0.83 |

| PLS Parcel 2—Harmonious Passion | 3.66 | 0.83 |

| PLS Parcel 3—Mastery L2 Goal | 3.72 | 0.79 |

| SSL—Short-Term | 3.07 | 0.95 |

| SSL—Long-Term | 3.63 | 0.99 |

| ICS 1 | 3.21 | 1.00 |

| ICS2 | 3.55 | 0.88 |

| ICS3 | 3.23 | 0.98 |

| ICS4 | 3.79 | 0.91 |

| ICS5 | 3.71 | 0.90 |

| ICS6 | 3.71 | 0.89 |

| ICS7 | 3.72 | 0.89 |

| ICS8 | 3.48 | 0.90 |

| ICS9 | 3.56 | 0.88 |

| Variables | LM | ICS | PLS | SSL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM | - | |||

| ICS | 0.34 *** | - | - | |

| PLS | 0.44 *** | 0.40 *** | - | - |

| SSL | 0.43 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.50 *** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Long, H. The Relationships of Self-Sustained English Learning, Language Mindset, Intercultural Communicative Skills, and Positive L2 Self: A Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080659

Yang L, Wang H, Zhang H, Long H. The Relationships of Self-Sustained English Learning, Language Mindset, Intercultural Communicative Skills, and Positive L2 Self: A Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2024; 14(8):659. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080659

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Luxi, Hui Wang, Hao Zhang, and Haiying Long. 2024. "The Relationships of Self-Sustained English Learning, Language Mindset, Intercultural Communicative Skills, and Positive L2 Self: A Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 14, no. 8: 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080659

APA StyleYang, L., Wang, H., Zhang, H., & Long, H. (2024). The Relationships of Self-Sustained English Learning, Language Mindset, Intercultural Communicative Skills, and Positive L2 Self: A Structural Equation Modeling Mediation Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 14(8), 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14080659