Analyzing Antecedent Configurations of Group Emotion Generation in Public Emergencies: A Multi-Factor Coupling Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis

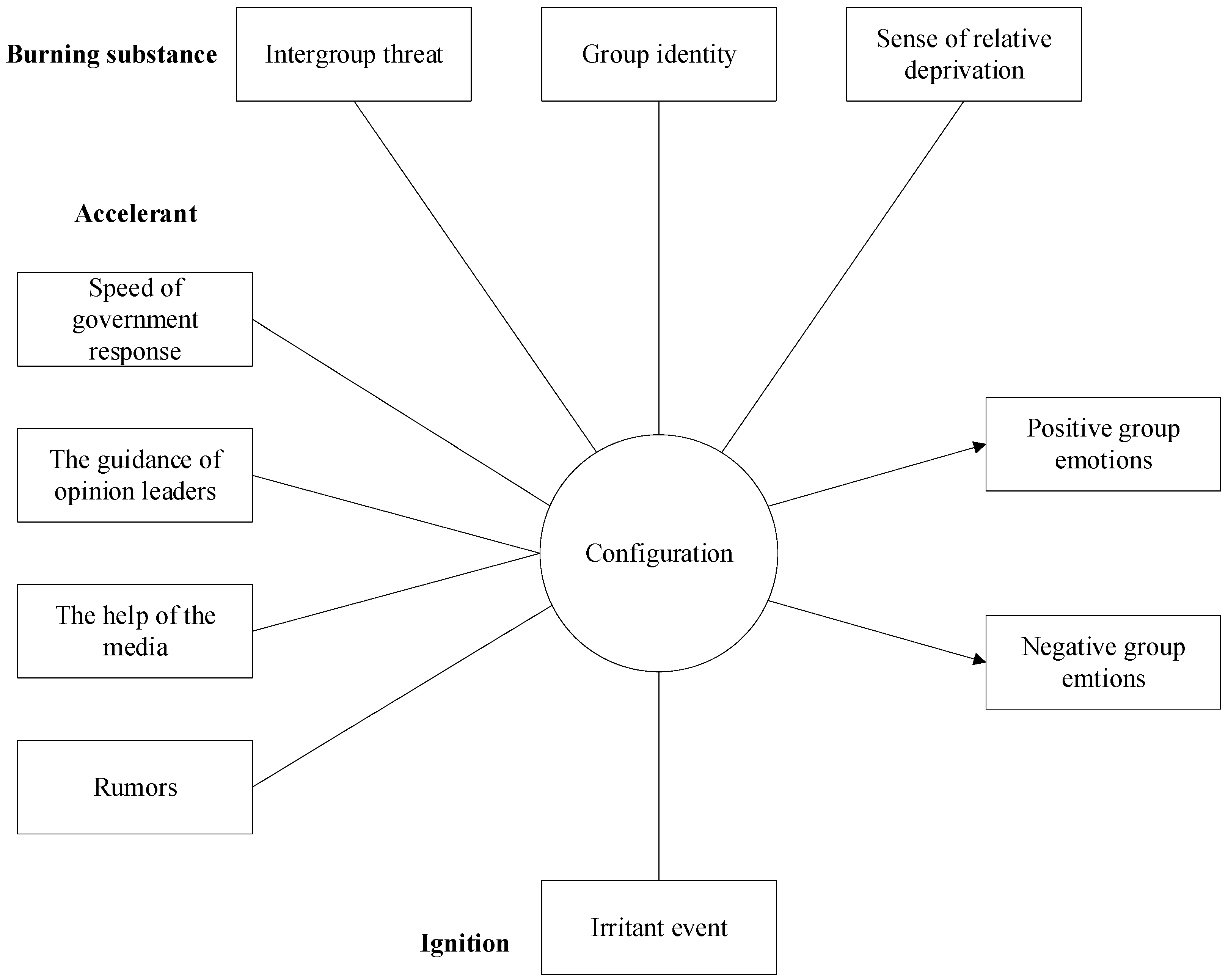

2.1. Social Combustion Theory

2.2. Intergroup Emotion Theory

2.3. Influencing Factors of Group Emotion

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Selection

3.2. Variable Selection and Assignment

3.2.1. Burning Substances

3.2.2. Accelerant

3.2.3. Ignition

3.3. FsQCA Method

3.4. Data Calibration

4. FsQCA Findings

4.1. Single-Factor Necessity Analysis

4.2. Conditional Configuration Analysis

4.3. Robustness Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aven, T. (2014). Risk, surprises and black swans: Fundamental ideas and concepts in risk assessment and risk management. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, D., & Cao, R. (2021). Analysis of factors that influence researchers’ data literacy using SEM and fsQCA. Journal of the China Society for Scientific and Technical Information, 40(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W., & Shen, J. (2023). Research on the global professional development of innovation-driven think tank knowledge services: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) based on 40 cases. Information Science, 41(5), 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, M. J., Kim, H., & Matthews, W. J. (2015). Age differences in social comparison tendency and personal relative deprivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Chen, T. (2015). Analysis of the evolution of public opinion in emergency events: From the perspective of the guiding role of opinion leaders. Information and Documentation Services, 2, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T., Wang, Y., Yang, J., & Cong, G. (2020). Modeling public opinion reversal process with the considerations of external intervention information and individual internal characteristics. Healthcare, 8(2), 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T., Wu, T., Yang, J., & Xu, B. (2024). Modeling of network public opinion communication based on social combustion theory under sudden social hot events. PLoS ONE, 19(11), e0311968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y., Li, L., Ybarra, O., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Symbolic threat affects negative self-conscious emotions. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 14, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Su, Z., & Zhou, L. (2022). Key factors and effective pathways of disaster relief information network dissemination. Journal of Information, 41(5), 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Wang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2017). The role of social identity in investor decision-making in reward-based crowdfunding: An analysis based on group emotion and efficiency path. Business Research, 3, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, M., Song, W., Zhao, Z., Chen, T., & Chiang, Y. (2024). Emotional contagion on social media and the simulation of intervention strategies after a disaster event: A modeling study. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikara, M., Bruneau, E., Van Bavel, J. J., & Saxe, R. (2014). Their pain gives us pleasure: How intergroup dynamics shape empathic failures and counter-empathic responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G. A., Haslam, C., & Jetten, J. (2014). Depression and social identity: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(3), 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y., Zhang, P., Lan, X., & Wu, L. (2019). Research on derivative public opinion sentiment analysis of weibo burst events for time series: A case study of the “6.22” hangzhou nanny arson derivative public opinion event. Information Science, 37(3), 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- De la Sablonnire, R., Tougas, F., Taylor, D. M., Crush, J., Mcdonald, D., & Perenlei, O. R. (2015). Social change in mongolia and south africa: The impact of relative deprivation trajectory and group status on well-being and adjustment to change. Social Justice Research, 28(1), 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Lu, Q., Li, L., Li, H., & Sarkar, A. (2023). Measuring the impact of relative deprivation on tea farmers’ pesticide application behavior: The case of Shaanxi, Sichuan, Zhejiang, and Anhui province, China. Horticulturae, 9(3), 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N., & Qi, K. (2023). Research on public opinion risk identification of social emotions infected by network rumors based on HHM. Network Security Technology & Application, 12, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H., Song, Y., & He, X. (2023). Research on villager land expropriation cluster behavior in the context of rural revitalization. Information Technology and Management Applications, 2(3), 14–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J. (2010). Identifying single necessary conditions with nca and fsqca. Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, K., & Waldzus, S. (2014). Group-based guilt and reparation in the context of social change. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44(4), 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N., & Haslam, S. A. (2012). Social identity theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 2, 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Feierabend, I. K., & Gurr, T. R. (1970). Why men rebel. American Political Science Association, 65(1), 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P. C. (2007). A set-theoretic approach to organizational configurations. The Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1180–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P. C. (2011). Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions: The emerging science of positive psychology is coming to understand why it’s good to feel good. American Scientist, 91(4), 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition & Emotion, 19(3), 313–332. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T., & Hao, Y. (2020). Research on the dynamics of COVID-19 public opinion dissemination in social media: A case study of weibo. Journalism Frontier, 6, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Prieto, P., & Scherer, K. R. (2016). Connecting social identity theory and cognitive appraisal theory of emotions. In Social identities (pp. 189–208). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., Sun, S., Niu, F., & Li, F. (2017). A sentiment semantics-enhanced deep learning model for Weibo sentiment analysis. Journal of Computer Research and Development, 40(4), 773–790. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W., & Yang, P. (2023). A study on influencing factors of users’ participation behavior in knowledge communities with scientific and technological innovation as the topic: A MOA framework-based configuration analysis. Information Studies: Theory & Application, 46(2), 90–99+70. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, L., Katarya, R., & Sachdeva, S. (2020). Recognition of opinion leaders coalitions in online social network using game theory. Knowledge-Based Systems, 203, 106158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelic, M., Corkalo Biruski, D., & Ajdukovic, D. (2013). Predictors of collective guilt after the violent conflict. Collegium Antropologicum, 37(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jetten, J., Haslam, C., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G., & Jones, J. M. (2014). How groups affect our health and well-being: The path from theory to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H., Su, B., & Lv, M. (2014). A study on the willingness of emotional dissemination behavior of online rumor information: From the perspective of social hotspot events. Journal of Information, 33(11), 34–39+28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M., & Cao, H. (2020). Research on emergency network public opinion generation mechanism in the information ecological horizon—Based on 40 emergencies through csQCA. Information Science, 38(3), 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., & Li, W. (2019). Evolution mechanism of public crisis network public opinion: Path and motivation—Taking animal epidemic crisis as an example. Chinese Public Administration, 2, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S., Wang, Y., Xue, J., Zhao, N., & Zhu, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active Weibo users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W., Jiang, H., & Zeng, F. (2022). Research on generating mechanism of reversal intensity of network public opinion in public emergencies—fsQCA analysis based on multiple cases. Journal of Intelligence, 41(11), 129–136+54. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C., Liu, L., Wang, D., & Chen, W. (2022). The mechanism of collective ritual promoting group emotional contagion. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(8), 1870–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Zhu, X., & Li, C. (2023). Research on the negative online rumors dissemination of sudden public crisis events on the influence of disappointment. Information Studies: Theory & Application, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Long, F., Ye, Z., & Liu, G. (2023). Intergroup threat, knowledge of the outgroup, and willingness to purchase ingroup and outgroup products: The mediating role of intergroup emotions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(2), 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D., & Hong, D. (2022). Emotional contagion: Research on the influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 931835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, S., & Sun, J. (2020). How does personal relative deprivation affect mental health among the older adults in China? Evidence from panel data analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Common method Bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. Journal of Retailing, 88(4), 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(4), 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitner, A. T., Mackie, D. M., & Smith, E. R. (2006). Evidence for the regulatory function of intergroup emotion: Emotional consequences of implemented or impeded intergroup action tendencies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(6), 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W. (2001). The social physics and the warning system of China′s social stability. Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, I. O., & Woodside, A. G. (2021). Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in information systems and marketing. International Journal of Information Management, 58(3), 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. S. (2013). Does twitter motivate involvement in politics? Tweeting, opinion leadership, and political engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, A. L., Bitencourt, L., Fróes, A. C. F., Cazumb, M. L. B., Campos, R. G. B., de Brito, S. B. C. S., & Simões e Silva, A. C. (2020). Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 566212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G., & Cheng, X. (2023). The generation mechanism of reversal news public opinion based on social burning theory. Information Science, 41(1), 80–85+109. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, W., Xu, L., Jing, Y., Han, W., & Hu, F. (2022). Relative deprivation, depression and quality of life among adults in Shandong Province, China: A conditional process analysis based on social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 312, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragin, C. C. (2006). Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Analysis, 14(3), 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C. C. (2010). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C. C., & Fiss, P. C. (2008). Net effects analysis versus configurational analysis: An empirical demonstration. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond, 240, 190–212. [Google Scholar]

- Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. (2017). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques. China Machine Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, F. (2012). Group identification, social relationships, and health. In the social cure: Identity, health and well-being (pp. 21–37). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2010). Standards of good practice in qualitative comparative analysis (Qca) and fuzzy-sets. Comparative Sociology, 9(3), 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2012). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, F., & Gao, J. (2010). A sociophysics explanation of the causes of collective events: Introduction of the social combustion theory. Journal of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, 12(6), 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. R. (1993). Social identity and social emotions: Toward new conceptualizations of prejudice. In Affect, cognition and stereotyping (pp. 297–315). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E. R., Seger, C. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2007). Can emotions be truly group level? Evidence regarding four conceptual criteria. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(3), 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A. M., Piff, P. K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C. L., Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review, 9(3), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, S. A. (1949). An analysis of conflicting social norms. American Sociological Review, 14(6), 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S., Sun, M., & Zhang, J. (2018). An evolution model of network public opinion on emergencies based on generalized stochastic petri nets. Information Science, 36(8), 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(3), 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y., Li, S., Fang, Z., She, Y., Wang, Q., Wang, F., & Jing, X. (2022). Dissemination influence of internet public opinion leaders in emergencies based on SNA. Journal of Xi’an University of Science and Technology, 42(2), 290–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., & Qiu, X. (2021). Research on the mutual influence of internet rumor and panic emotion’s parallel spreading. Journal of Intelligence, 40(4), 200–207+199. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., & Zhang, H. (2024). Research on the governance of online public opinion in universities in the era of self media: Based on the theory of social burning. Science & Technology for China’s Mass Media, 1, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Song, Y., Liu, D., Chen, H., & Fang, J. (2021). Network emotion propagation model of public health emergencies based on social combustion theory. China Safety Science Journal, 31(2), 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H., & Yin, J. (2024). On the evolutionary mechanism of network public opinion in colleges based on social combustion theory. Journal of Ningbo University (Educational Science Edition), 46(2), 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T., Bruder, M., Robertson, S., Van Tilburg, W. A. P., & Sedikides, C. (2014). Collective nostalgia: A group-level emotion that confers unique benefits on the group. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 844–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., & Duan, Q. (2024). The generation mechanism of anxiety in AI face-swapping technology: Findings of SEM and fsQCA. Documentation, Information & Knowledge, 41(5), 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F., Yang, J., Tian, M., & Xu, G. (2020). Antecedents and coping strategies of WeChat users’ regret based on SEM and FsQCA. Library and Information Service, 64(16), 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, T., Chen, H., Yue, G., & Yao, Q. (2013). The effect of social identity on group attitude: The role of intergroup threat and group-based emotion as mediators. Journal of Psychological Science, 36(1), 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L., Dong, G., & Jin, L. (2007). A review of research on brain response differences between positive and negative emotions. Psychological and Behavioral Research, 3, 224–228. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C., Wang, D., Yang, Y., & Fu, D. (2022). Research on the dynamics model of group emotions evolution based on topic resonance. Systems Engineering—Theory & Practice, 42(9), 2523–2539. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, M., Luo, J., Wang, S., & Zhong, J. (2018). Does time pressure influence employee silence? A study using SEM and fsQCA. Nankai Business Review, 21(1), 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J., & Lin, C. (2022). Exploring the transmission mechanism of university students’ emotions in online public opinion based on social combustion theory. Applied & Educational Psychology, 3(1), 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R., & Zhang, F. (2015). The mechanism of group identity in collective behavior. Advances in Psychological Science, 23(9), 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y., & Tang, W. (2013). A group emotion model based on opinion identification. Computer Applications Research, 30(10), 2996–3000. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y., Tang, W., & Li, W. (2015). Emotion modeling of crowd based on social network. Application Research of Computers, 32(1), 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., & Chen, Q. (2012). Research on the occurrence of online collective events from the perspective of social combustion theory. E-Government, 7, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Yi, S., Wang, H., & Xiang, M. (2024). The formation path of network public opinion reversal from The perspective of symbiosis theory—Based on qualitative comparative analysis of fsQCA. Information Science, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N., & Xiao, Q. (2023). Research on the evolution of group emotions in emergencies under network public opinion. Information Research, 11, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. (2013). Intergroup threat and intentions of collective behavior: A dual-pathway model of collective events. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 45(12), 1410–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Zhou, J., & Wang, E. (2009). Antecedents of group relative deprivation and its impact on collective behavior: An empirical study based on a survey of the wenchuan earthquake disaster area. Journal of Public Administration, 6(4), 69–77+126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T., & Tao, X. (2023). Research on the mechanism and governance of information epidemic generation in sudden public health incidents based on social burning theory. Public Communication of Science & Technology, 15(2), 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. (2017). Factors influencing the propagation tendency of public opinion information in sudden public events: A research perspective based on public negative emotions. Information Theory and Practice, 40(7), 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D., & Wang, G. (2020). Influencing factors and mechanism of netizens’ social emotions in emergencies—Qualitative comparative analysis of multiple cases based on ternary interactive determinism (QCA). Journal of Intelligence, 39(3), 95–104. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Name | Time | ID | Name | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sichuan Airlines diversion | 14 May 2018 | 21 | Bao Yuming, an executive at a listed company, is suspected of sexually assaulting his adopted daughter | 8 April 2020 |

| 2 | Qingyang girl jumping from building | 20 June 2018 | 22 | Abundance nest express cabinet overtime charge controversy | 27 March 2020 |

| 3 | Changsheng and other vaccine fraud | 15 July 2018 | 23 | “Fake milk powder” has led to the emergence of big-head dolls in Hunan | 12 May 2020 |

| 4 | Shouguang flood discharge | 19 August 2018 | 24 | A woman in Hangzhou mysteriously disappeared late at night | 18 July 2020 |

| 5 | On G334 high-speed train, a man pretending to be sick to obtain a seat | 21 August 2018 | 25 | Online exposure of Pinduoduo’s grocery shopping staff dying suddenly on the way to work | 3 January 2021 |

| 6 | A woman takes a Didi Hitch ride in Yueqing and is killed | 25 August 2018 | 26 | A 23-year-old woman in Changsha jumped out of the window of a truck and died | 21 February 2021 |

| 7 | Jiangsu Kunshan BMW man was killed after being slashed | 28 August 2018 | 27 | 21 killed in mountainous marathon accident in Gansu province | 22 May 2021 |

| 8 | Wanzhou bus falling into the river | 28 October 2018 | 28 | A gas explosion in Shiyan has killed 25 people | 13 June 2021 |

| 9 | Zhai Tianlin was accused of plagiarism | 8 February 2019 | 29 | Extremely heavy rainstorm in Henan | 19 July 2021 |

| 10 | There was an explosion at the Xiangshui chemical plant in Yancheng | 21 March 2019 | 30 | Female employees of Alibaba were assaulted | 7 August 2021 |

| 11 | Forest fire broke out in Liangshan | 30 March 2019 | 31 | A female passenger is dragged by security guards on the Xi’an subway | 30 August 2021 |

| 12 | A 6.0-magnitude earthquake struck Changning in Yibin | 17 June 2019 | 32 | Many places in Northeast China cut off electricity during peak hours | 25 September 2021 |

| 13 | The skeleton of a missing teacher in Hunan province was buried in the playground after 16 years | 20 June 2019 | 33 | A mother of eight children in Feng County is mentally unstable and tied to an iron chain | 28 January 2022 |

| 14 | A girl in Hangzhou went missing after being taken by two tenants | 9 July 2019 | 34 | MU5735 with 132 people on board crashed in Teng County | 21 March 2022 |

| 15 | Super Typhoon Lekima made landfall | 8 August 2019 | 35 | A building collapsed in Changsha | 29 April 2022 |

| 16 | Wuhan and other places have been hit by pneumonia caused by the novel coronavirus | 30 December 2019 | 36 | D2809 hit mudslide derailment at Rongjiang Station | 4 June 2022 |

| 17 | A woman drove a Benz into Forbidden City | 17 January 2020 | 37 | A group of men beat up a girl at a barbecue restaurant in Tangshan | 10 June 2022 |

| 18 | The use of materials by the Hubei Red Cross Society has been questioned | 30 January 2020 | 38 | 27 killed and 20 injured after a passenger bus overturned at high speed in Guizhou province | 18 September 2022 |

| 19 | Dr. Li Wenliang, the whistleblower of the epidemic, has died of COVID-19 | 6 February 2020 | 39 | 2 dead and 3 injured after a Tesla loses control in Chaozhou | 13 November 2022 |

| 20 | A designated quarantine hotel collapsed in Quanzhou | 7 March 2020 | 40 | 10 dead in a high-rise residential building fire in Urumqi | 25 November 2022 |

| Variables | Coding Judgment | Assign | Instructions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of relative deprivation | There is a sense of relative deprivation | 1 | Condition variable |

| There is no sense of relative deprivation | 0 | ||

| Group identity | There is no group identity | 1 | Condition variable |

| There is group identity | 0 | ||

| Intergroup threat | There is intergroup threat | 1 | Condition variable |

| There is no intergroup threat | 0 | ||

| Speed of government response | The speed of the official response | days | Condition variable |

| The guidance of opinion leaders | The product of the influence of the opinion leaders participating in the discussion and the number of posts | Degree of participation | Condition variable |

| The help of the media | The number of media participating in the topic discussion | number | Condition variable |

| Rumors | Rumors arise | 1 | Condition variable |

| No rumors | 0 | ||

| Irritant event | Irritant events occurred | 1 | Condition variable |

| No irritant events occurred | 0 | ||

| Positive group emotions | Degree of positive emotion | The proportion of positive emotion | Result variable |

| Negative group emotions | Degree of negative emotion | The proportion of negative emotion | Result variable |

| Category | Element Name | Calibrated Anchor Point | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Affiliated Points | Intersection Points | Completely Unaffiliated Points | ||

| Condition variable | Sense of relative deprivation | 1 | - | 0 |

| Group identity | 1 | - | 0 | |

| Intergroup threat | 1 | - | 0 | |

| Speed of government response | 42.500 | 2.000 | 1.000 | |

| The guidance of opinion leaders | 111.450 | 40.500 | 13.950 | |

| The help of the media | 471.000 | 183.500 | 80.500 | |

| Rumors | 1 | - | 0 | |

| Irritant event | 1 | - | 0 | |

| Result variable | Positive group emotions | 1 | - | 0 |

| Negative group emotions | 1 | - | 0 | |

| Antecedent Condition | Outcome Variable: Positive Group Emotion | Outcome Variable: Negative Group Emotion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| Sense of relative deprivation | 0.7350 | 0.4398 | 0.7230 | 0.5031 |

| ~Sense of relative deprivation | 0.2650 | 0.4180 | 0.2770 | 0.5082 |

| Group identity | 0.0964 | 0.4181 | 0.1007 | 0.5081 |

| ~Group identity | 0.9036 | 0.4356 | 0.8993 | 0.5041 |

| Intergroup threat | 0.6107 | 0.7382 | 0.4842 | 0.6806 |

| ~Intergroup threat | 0.7880 | 0.5333 | 0.8437 | 0.6640 |

| Speed of government response | 0.6585 | 0.6582 | 0.6043 | 0.7025 |

| ~Speed of government response | 0.7997 | 0.6129 | 0.7720 | 0.6881 |

| The guidance of opinion leaders | 0.6859 | 0.6287 | 0.6981 | 0.7441 |

| ~The guidance of opinion leaders | 0.7798 | 0.6423 | 0.7038 | 0.6741 |

| The help of the media | 0.8848 | 0.4387 | 0.8747 | 0.5043 |

| ~The help of the media | 0.1152 | 0.3998 | 0.1253 | 0.5057 |

| Rumors | 0.6881 | 0.4118 | 0.7424 | 0.5166 |

| ~Rumors | 0.3119 | 0.4920 | 0.2576 | 0.4725 |

| Irritant event | 0.6242 | 0.4012 | 0.7328 | 0.5477 |

| ~Irritant event | 0.3758 | 0.5016 | 0.2672 | 0.4147 |

| Raw Coverage | Unique Coverage | Consistency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RD*~GI*TG*~OL*HM*IT*~IE | 0.1198 | 0.1198 | 0.9984 |

| ~RD*GI*TG*~OL*~HM*~IT*~RC*~IE | 0.0289 | 0.0289 | 1 |

| RD*~GI*TG*~OL*~HM*IT*~RC*IE | 0.0859 | 0.0859 | 0.9935 |

| ~RD*~GI*TG*OL*HM*IT*~RC*IE | 0.0375 | 0.0375 | 1 |

| Solution coverage | 0.2720 | ||

| Solution consistency | 0.9972 | ||

| Conditional Configuration | H1a | H1b | H1c | H1d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of relative deprivation | ● | ⓧ | · | ⓧ |

| Group identity | ⊗ | · | ⊗ | ⊗ |

| Intergroup threat | · | ⊗ | · | · |

| Speed of government response | · | ● | ● | ● |

| The guidance of opinion leaders | ⓧ | ⊗ | ⓧ | · |

| The help of the media | · | ⊗ | ⊗ | · |

| Rumors | ⓧ | ⓧ | ⓧ | |

| Irritant event | ⓧ | ⊗ | · | · |

| Consistency | 0.9984 | 1 | 0.9935 | 1 |

| Original coverage | 0.1198 | 0.0289 | 0.0859 | 0.0375 |

| Unique coverage | 0.1198 | 0.0289 | 0.0859 | 0.0375 |

| Consistency of solution | 0.9972 | |||

| The coverage of the solution | 0.2720 | |||

| Raw Coverage | Unique Coverage | Consistency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RD*~GI*~TG*~OL*~HM*IT*IE | 0.3028 | 0.0703 | 0.9593 |

| ~RD*GI*~TG*~OL*HM*IT*RC | 0.0714 | 0.0714 | 0.8791 |

| RD*~GI*~TG*~OL*IT*RC*IE | 0.2427 | 0.0449 | 0.8608 |

| ~RD*~GI*TG*OL*HM*RC*IE | 0.0551 | 0.0551 | 1 |

| ~RD*~GI*~TG*~OL*HM*IT*~RC*~IE | 0.0253 | 0.0253 | 1 |

| RD*~GI*TG*~OL*~HM*~IT*RC*IE | 0.0389 | 0.0389 | 0.9234 |

| RD*~GI*TG*OL*~HM*IT*RC*~IE | 0.0491 | 0.0491 | 1 |

| RD*~GI*~TG*OL*HM*IT*~RC*IE | 0.0768 | 0.0422 | 0.9572 |

| Solution coverage | 0.6295 | ||

| Solution consistency | 0.9133 | ||

| Conditional Configuration | H2a | H2b | H2c | H2d | H2e | H2f | H2g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of relative deprivation | · | ⓧ | · | ⓧ | ⊗ | · | · |

| Group identity | ⊗ | · | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⓧ | ⊗ |

| Intergroup threat | · | · | · | ● | ⓧ | · | |

| Speed of government response | ⓧ | ⊗ | ⓧ | · | ⓧ | · | ● |

| The guidance of opinion leaders | ⓧ | ⊗ | ⓧ | · | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● |

| The help of the media | ⊗ | ● | ● | · | ⓧ | ⊗ | |

| Rumors | ● | · | ● | ⓧ | · | · | |

| Irritant event | · | · | · | ⊗ | · | ⓧ | |

| Consistency | 0.9593 | 0.8791 | 0.8608 | 1 | 1 | 0.9234 | 1 |

| Original coverage | 0.3028 | 0.0714 | 0.2427 | 0.0551 | 0.0253 | 0.0389 | 0.0491 |

| Unique coverage | 0.0703 | 0.0714 | 0.0449 | 0.0551 | 0.0253 | 0.0389 | 0.0491 |

| Consistency of solution | 0.9133 | ||||||

| The coverage of the solution | 0.6295 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T. Analyzing Antecedent Configurations of Group Emotion Generation in Public Emergencies: A Multi-Factor Coupling Approach. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010041

Yan X, Liu Y, Chen Y, Liu T. Analyzing Antecedent Configurations of Group Emotion Generation in Public Emergencies: A Multi-Factor Coupling Approach. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Xiaohan, Yi Liu, Yan Chen, and Tiezhong Liu. 2025. "Analyzing Antecedent Configurations of Group Emotion Generation in Public Emergencies: A Multi-Factor Coupling Approach" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010041

APA StyleYan, X., Liu, Y., Chen, Y., & Liu, T. (2025). Analyzing Antecedent Configurations of Group Emotion Generation in Public Emergencies: A Multi-Factor Coupling Approach. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010041