Computer Self-Efficacy and Reactions to Feedback: Reopening the Debate in an Interpretive Experiment with Overconfident Students †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

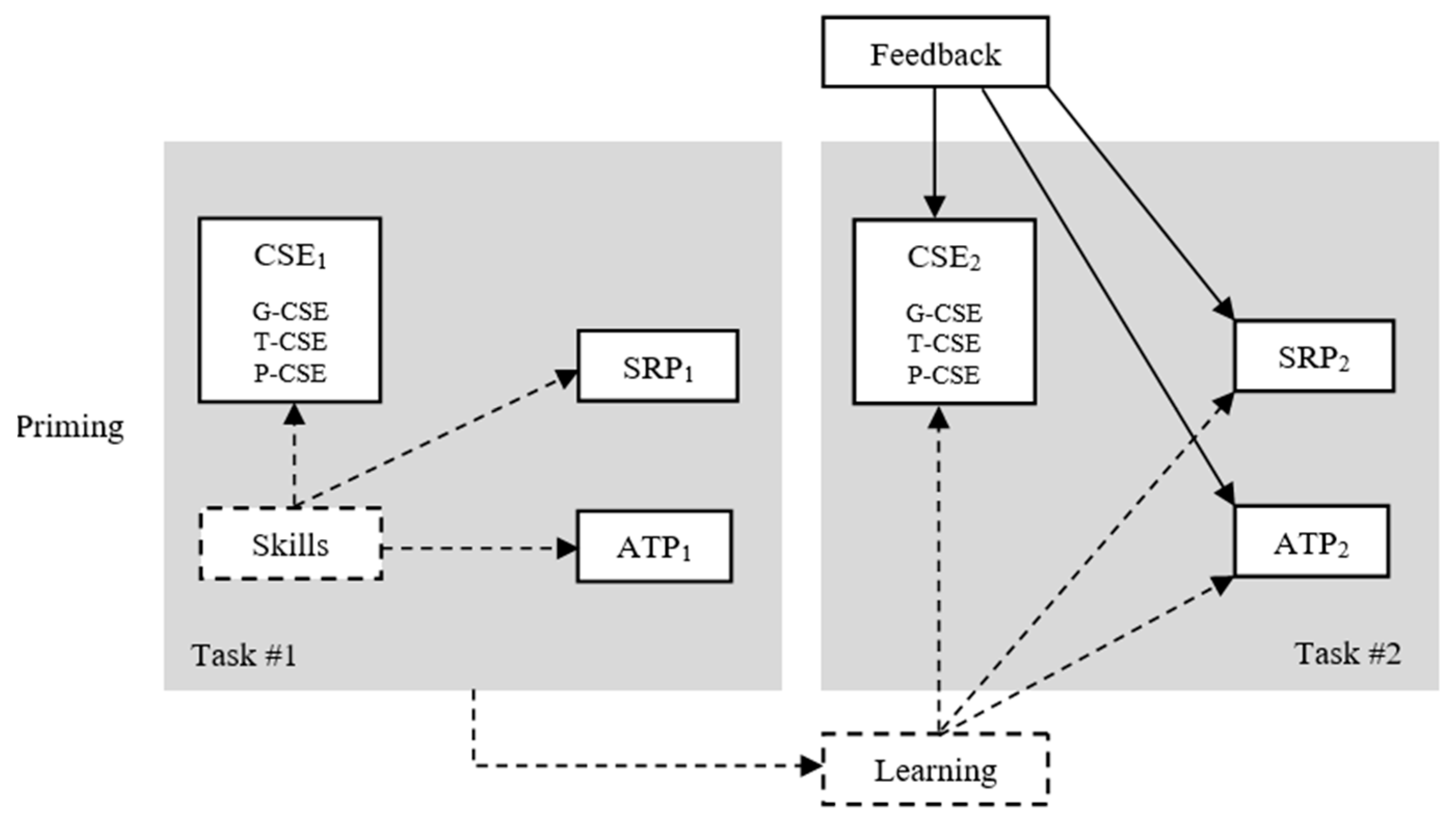

2.1. Computer Self-Efficacy

2.2. Self-Efficacy and Performance

2.3. Feedback and Learning

3. Method

| RGPOS | O1 | X1 | O2 |

| RGNEG | O3 | X2 | O4 |

| RGCTRL | O5 | – | O6 |

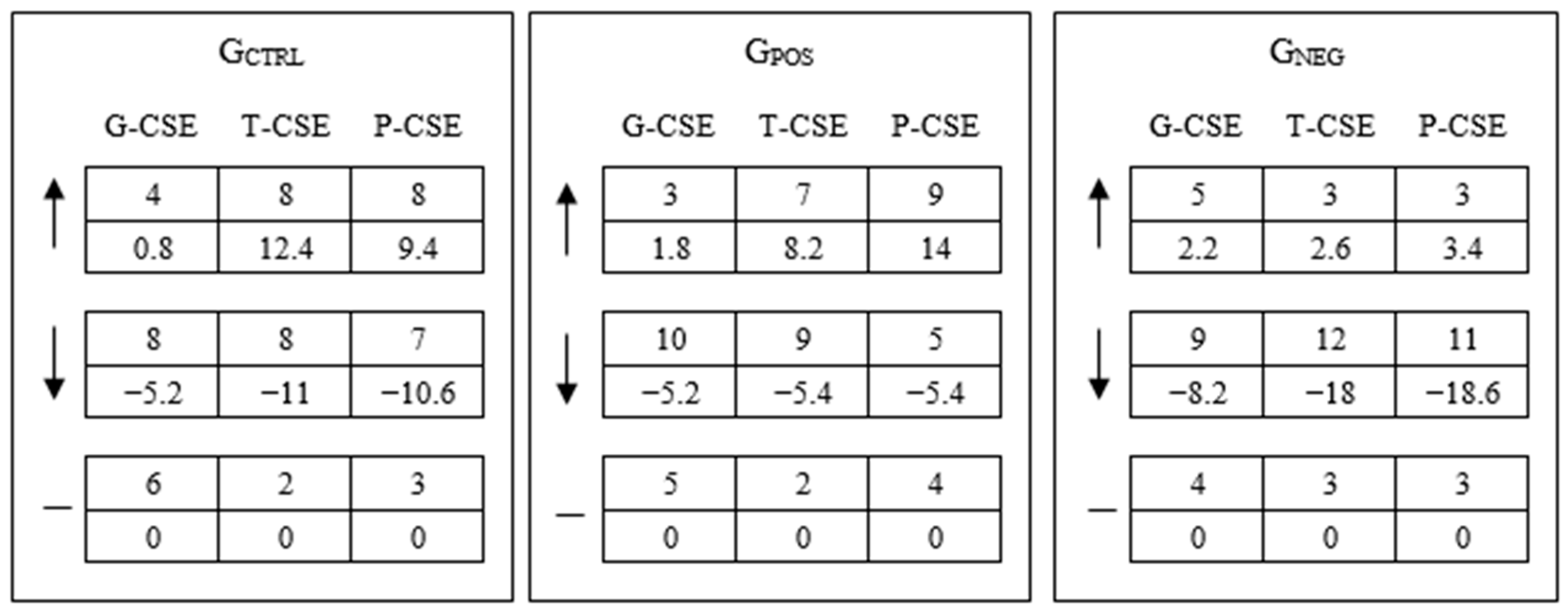

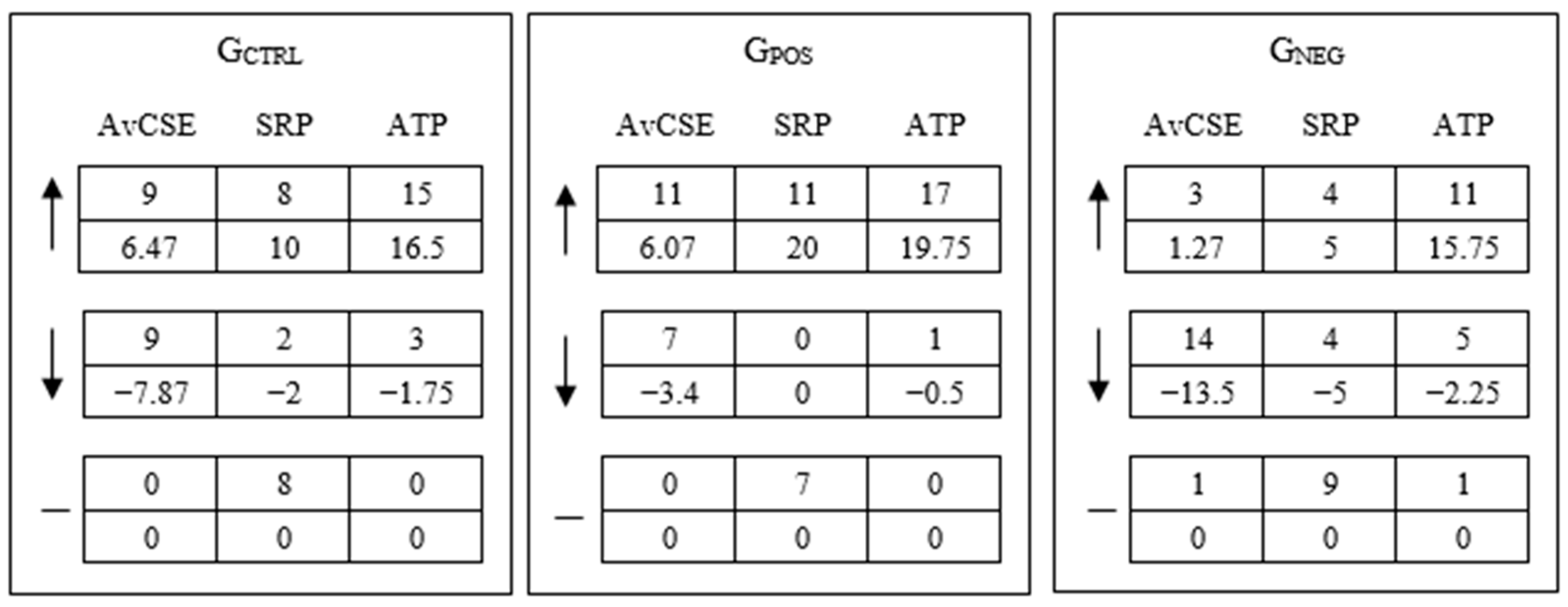

4. Results and Discussion

5. Implications for Theory and Practice

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. CSE Instrument Applied Before Each Task

- (G-CSE 1)

- Use a personal computer.

- (G-CSE 2)

- Install a computer software.

- (G-CSE 3)

- Use a computer software for the first time without help.

- (G-CSE 4)

- Use a computer software for the first time with help.

- (G-CSE 5)

- Use a computer software for the first time, a software which is similar to another one that I use.

- (T-CSE 1)

- Edit data in an electronic spreadsheet.

- (T-CSE 2)

- Use mathematical functions and logical operations in an electronic spreadsheet.

- (T-CSE 3)

- Use menu instructions/commands (edit, delete, filter, format, etc.) in an electronic spreadsheet.

- (T-CSE 4)

- Use data from one tab in another tab of the same electronic spreadsheet.

- (T-CSE 5)

- Work with charts in an electronic spreadsheet.

- (P-CSE 1)

- Use an electronic spreadsheet as a decision-support tool.

- (P-CSE 2)

- Use an electronic spreadsheet as a support tool for academic or professional tasks.

- (P-CSE 3)

- Use an electronic spreadsheet as a support tool in business analyses.

- (P-CSE 4)

- Use an electronic spreadsheet to analyze costs and benefits.

- (P-CSE 5)

- Use an electronic spreadsheet to analyze business investments in information technology.

Appendix B. Computer-Aided Decision Tasks

| Task #1 |

- The productivity paradox is a classical problem in the domain of IT investments. It refers to the doubt of whether a company’s IT infrastructure has a positive impact in the company’s results, particularly regarding the financial returns on investment and competitive advantage. Please reflect on the following case inspired on the productivity paradox and develop a spreadsheet application according to the instructions.

- Initial situation: You are the chief technology officer of a company (MINE) in the soft drinks industry with net financial assets of $7 million and market share of 10%. The main rival of MINE in the industry is company OTHER, which has $4 million in net financial assets and 20% of market share. You need to decide whether to upgrade MINE’s IT infrastructure due to prospective efficiency gains in its relationship with the supply chain and end customers. OTHER is about to make a similar decision.

- Scenario #1:

- If MINE decides to upgrade its IT infrastructure and OTHER does not, MINE will spend $1 million but in return MINE will take 5% from OTHER’s market share.

- Scenario #2:

- If OTHER decides to upgrade its IT infrastructure and MINE does not, OTHER will spend $3 million but in return OTHER will take 3% from MINE’s market share.

- Scenario #3:

- If both companies decide to upgrade their IT infrastructure, each of them loses 2% of market share due to a period of low discernment of the market.

- Scenario #4:

- If both companies decide not to upgrade their IT infrastructure, they do not spend money but each of them loses 6% of market share due to inefficiencies.

- Activities:

- Note: Maximum scores are informed in each activity. Participants did not know beforehand the score per activity. The maximum total score is 10.0.

- Please use the electronic spreadsheet available in your computer to do the following activities (template tables provided):

- (1)

- In cell B1, please insert the current time. [0.25 points]

- (2)

- In cell B2, please insert your name. [0.25 points]

- (3)

- In cell B3, please insert the current date. [0.25 points]

- (4)

- In the first tab of the spreadsheet, please:

- (a)

- Insert the net financial assets of each company (please assure that the cell is formatted for currency). [0.50 points]

- (b)

- Insert the market share of each company (please assure that the cell is formatted for percentage). [0.50 points]

- (c)

- Insert a title in each column (“Name of the company”, “Net assets”, “Market share”), put in bold the name of each company, and highlight in black the edges of the table. [0.75 points]

- (d)

- Rename the tab as “Information”. [0.25 points]

- (5)

- Use the second tab to fill the tables with the four scenarios, rename the tab as “Scenarios” [0.25 points], and:

- (a)

- Make it bold all column titles in all scenarios (“Company”, “Initial financial assets”, “IT cost”, “Final financial assets”, “Initial market share”, “Market share transfer”, “Final market share”). [0.25 points]

- (b)

- In cell A3, type “MINE”; in cell A4, type “OTHER”. [0.50 points]

- (c)

- In column “Initial financial assets” of Scenario #1, put the net financial assets of each company. [0.25 points]

- (d)

- In column “IT cost” of each scenario, put the corresponding investment costs. [0.25 points]

- (e)

- In column “Final financial assets” of each scenario, develop a formula to calculate the net financial assets after the IT investments. [0.50 points]

- (f)

- In column “Initial market share” of Scenario #1, put the initial market share of each company. [0.25 points]

- (g)

- In column “Market share transfer” of each scenario, put the corresponding values of share transfer and assure the cells are in percentage format (put a minus signal for market share lost). [0.50 points]

- (h)

- In column “Final market share” of each scenario, develop a formula to calculate the final market share of each company. [0.50 points]

- (i)

- Centralize all cells both horizontally and vertically. [0.50 points]

- (6)

- Rename the third tab as “Summary” [0.25 points], and fill in and format the summary table of the scenarios according to the example below:

| OTHER | |||||||

| invests | does not invest | ||||||

| MINE | invests | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) |

| OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | ||

| does not invest | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | |

| OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | ||

- (a)

- The table must be equal to the given example (except for the real values) and filled in using the spreadsheet’s command that retrieves data from another tab (the “Scenarios” tab). [0.75 points]

- (b)

- Develop a bar chart entitled “Final financial assets” with a note comparing the financial assets of both companies in the case they upgrade their IT infrastructure. [1.00 points]

- (c)

- In tab “Information”, put in cell B4 the current time. [0.25 points]

- (d)

- In that same tab, answer in cell A10 what is the expected scenario for MINE and for OTHER, and explain why. [1.00 points]

- (e)

- What is the main decision variable in this problem? [0.25 points]

| Task #2 |

- Initial situation and scenarios:

- Note: the problematic situation and the scenarios are similar to those in Task #1, except for the different numbers in financial assets and market share of each company. The intention was to let the students reflect once again on the logics of the prisoner’s dilemma and, by changing numbers, make them intrigued as to whether the decision would be similar to the previous one or not. In order to save space, we will not repeat the problematic situation here, since merely changing the numbers does not affect the decision logics of this type of problem.

- Activities:

- Note: Maximum scores are informed in each activity. Participants did not know beforehand the score per activity. The maximum total score is 10.0.

- Please use the electronic spreadsheet available in your computer to do the following activities (template tables provided):

- (1)

- In cell B1, please insert the current time. [0.25 points]

- (2)

- In cell B2, please insert your name. [0.25 points]

- (3)

- In cell B3, please insert the current date. [0.25 points]

- (4)

- In the first tab of the spreadsheet, please:

- (a)

- Insert the net financial assets of each company (please assure that the cell is formatted for number with thousand separator and two decimal places). [0.50 points]

- (b)

- Insert the market share of each company (please assure that the cell is formatted for percentage). [0.50 points]

- (c)

- Fill in grey and highlight the edges of cells A6, B6 and C6. [0.75 points]

- (d)

- Rename the first tab as “Information”. [0.25 points]

- (5)

- Use the next tab to fill the tables with the four scenarios and rename the tab as “Scenarios”. [0.25 points] and:

- (a)

- Make it blue all column titles in all scenarios (“Company”, “Initial financial assets”, “IT cost”, “Final financial assets”, “Initial market share”, “Market share transfer”, “Final market share”). [0.25 points]

- (b)

- In cell A3, type “MINE”; in cell A4, type “OTHER”. [0.50 points]

- (c)

- In column “Initial financial assets” of Scenario #1, put the net financial assets of each company. [0.25 points]

- (d)

- In column “IT cost” of each scenario, put the corresponding investment costs. [0.25 points]

- (e)

- In column “Final financial assets” of each scenario, develop a formula to calculate the net financial assets after the IT investments. [0.50 points]

- (f)

- In column “Initial market share” of Scenario #1, put the initial market share of each company. [0.25 points]

- (g)

- In column “Market share transfer” of each scenario, put the corresponding values of share transfer and assure the cells are in percentage format (put a minus signal for market share lost). [0.50 points]

- (h)

- In column “Final market share” of each scenario, develop a formula to calculate the final market share of each company. [0.50 points]

- (i)

- Justify to the left and to the bottom all cells. [0.50 points]

- (6)

- Rename the third tab as “Summary” [0.25 points], and fill in and format the summary table of the scenarios according to the example below:

| OTHER | |||||||

| invests | does not invest | ||||||

| MINE | invests | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) |

| OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | ||

| does not invest | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | MINE | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | |

| OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | OTHER | (post-investment financial assets) | (post-investment market share) | ||

- (a)

- The table must be equal to the given example (except for the real values) and filled in using the spreadsheet’s command that retrieves data from another tab (the “Scenarios” tab). [0.75 points]

- (b)

- Develop a line chart entitled “Final financial assets” with a note comparing the financial assets of both companies in the case MINE upgrades its IT infrastructure and OTHER does not. [1.00 points]

- (c)

- In tab “Information”, put in cell B4 the current time. [0.25 points]

- (d)

- In that same tab, answer in cell A10 what is the expected scenario for MINE and for OTHER, and explain why. [1.00 points]

- (e)

- What is the main decision variable in this problem? [0.25 points]

| 1 | The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting these discussions. |

| 2 | The statement on ethical research was shared with the publisher. |

| 3 | https://aisnet.org/page/SeniorScholarListofPremierJournals, accessed on 26 March 2025. |

| 4 | For instance: Butler University (https://www.butler.edu/academics/core/components/analytic-reasoning, accessed on 26 March 2025), Chicago State University (https://www.csu.edu/humanresources/empdev/documents/AnalyticalThinking.pdf, accessed on 26 March 2025), and University of Wisconsin Eau-Claire (https://www.uwec.edu/academics/programs/undergraduate/analytical-reasoning/, accessed on 26 March 2025). |

| 5 | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academic_grading_in_the_United_States, accessed on 26 March 2025. |

| 6 | The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for this remark. |

| 7 | The authors thank another anonymous reviewer for this remark. |

| 8 | The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this discussion. |

References

- Aesaert, K., Voogt, J., Kuiper, E., & Van Braak, J. (2017). Accuracy and bias of ICT self-efficacy: An empirical study into students’ over- and underestimation of their ICT competences. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M. C., Banker, R. D., & Ravindran, S. (2003). The new productivity paradox. Communications of the ACM, 46(3), 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseel, F., Lievens, F., & Levy, P. E. (2007). A self-motives perspective on feedback- seeking behavior: Linking organizational behavior and social psychology research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(3), 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseel, F., Lievens, F., & Schollaert, E. (2009). Reflection as a strategy to enhance task performance after feedback. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 110(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attali, Y., & Van Der Kleij, F. (2017). Effects of feedback elaboration and feedback timing during computer-based practice in mathematics problem solving. Computers & Education, 110, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Cervone, D. (1986). Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 38(1), 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J. W., & Schmidt, A. M. (2018). Negative relationships between self-efficacy and performance can be adaptive: The mediating role of resource allocation. Journal of Management, 44(2), 555–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, S., & Murray, K. B. (2018). Feedback, task performance, and interface preferences. European Journal of Information Systems, 27(6), 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, M., & Danaher, K. (2012). Interpreting and reacting to feedback in stereotype-relevant performance domains. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, H., Pelham, B. W., DeHart, T., & Carvallo, M. (2001). Overconfidence as dissonance reduction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(5), 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovoi, L., Schmidtke, K., & Vlaev, I. (2022). The effects of feedback valance and progress monitoring on goal striving. Current Psychology, 41, 4574–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budworth, M.-H., Latham, G. P., & Manroop, L. (2015). Looking forward to performance improvement: A field test of the feedforward interview for performance management. Human Resource Management, 54(1), 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton-Jones, A., & Grange, C. (2013). From use to effective use: A representation theory perspective. Information Systems Research, 24(3), 632–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabestrero, R., Quirós, P., Santos, O. C., Salmeron-Majadas, S., Uria-Rivas, R., Boticario, J. G., Arnau, D., Arevalillo-Herráez, M., & Ferri, F. J. (2018). Some insights into the impact of affective information when delivering feedback to students. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37(12), 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1966). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, N. G. (2003). IT doesn’t matter. Harvard Business Review, 5–12. Available online: https://www.classes.cs.uchicago.edu/archive/2014/fall/51210-1/required.reading/ITDoesntMatter.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Chen, X., Breslow, L., & DeBoer, J. (2018). Analyzing productive learning behaviors for students using immediate corrective feedback in a blended learning environment. Computers & Education, 117, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrier, B., Compagnone, P., Carrizales, A., Brisset, C., & Lannegrand, L. (2020). Emerging adult self-perception and link with adjustment to academic context among female college students. European Review of Applied Psychology, 70(5), 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutumisu, M. (2019). The association between feedback-seeking and performance is moderated by growth mindset in a digital assessment game. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutumisu, M., & Lou, N. M. (2020). The moderating effect of mindset on the relationship between university students’ critical feedback-seeking and learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 112, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutumisu, M., & Schwartz, D. L. (2018). The impact of critical feedback choice on students’ revision, performance, learning, and memory. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and end user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (2003). The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(4), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimotakis, N., Mitchell, D., & Maurer, T. (2017). Positive and negative assessment center feedback in relation to development self-efficacy, feedback seeking, and promotion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(11), 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, J. P., & McMurtrey, M. (2007). Introducing task-based general computer self-efficacy: An empirical comparison of three general self-efficacy instruments. Interacting with Computers, 19, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlinger, J., Mitchum, A. L., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Understanding overconfidence: Theories of intelligence, preferential attention, and distorted self-assessment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 63, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, T., Jacobsen, C., Fleming, S. M., & De Martino, B. (2017). Explicit representation of confidence informs future value-based decisions. Nature Human Behavior, 1, 0002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, K. A., & Dexter-Mazza, E. T. (2004). Using self-monitoring with an adolescent with disruptive classroom behavior: Preliminary analysis of the role of adult feedback. Behavior Modification, 28(3), 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M. E. (1987). Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Academy of Management Review, 12(3), 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M. E., Schwoerer, C., & Rosen, B. (1989). Effects of alternative training methods on self-efficacy and performance in computer software training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(6), 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vallejo, C., & Bonham, A. (2007). Aligning confidence with accuracy: Revisiting the role of feedback. Acta Psychologica, 125(2), 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V., Lyytinen, K., Srinivasan, A., & Tan, B. C. Y. (2008). Contributing to rigorous and forward thinking explanatory theory. Journal of the AIS, 9(2), 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., & Bostrom, R. P. (2019). A revision of computer self-efficacy conceptualizations in information systems. The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 50(2), 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilary, G., & Menzly, L. (2006). Does past success lead analysts to become overconfident? Management Science, 52(4), 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingshead, S. J., Wohl, M. J. A., & Santesso, D. (2019). Do you read me? Including personalized behavioral feedback in pop-up messages does not enhance limit adherence among gamblers. Computers in Human Behavior, 94, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogerheide, V., Loyens, S. M. M., Jadi, F., Vrins, A., & Van Gog, T. (2017). Testing the model-observer similarity hypothesis with text-based worked examples. Educational Psychology, 37(2), 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogerheide, V., Van Wermeskerken, M., Van Nassau, H., & Van Gog, T. (2018). Model-observer similarity and task-appropriateness in learning from video modeling examples: Do model and student gender affect test performance, self-efficacy, and perceived competence? Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introna, L. D., & Whitley, E. D. (2000). About experiments and style: A critique of laboratory research in information systems. Information Technology & People, 13(3), 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. American Psychologist, 64(6), 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, R., Mitra, A., & Schmidt, D. (2012). Computer self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational & End User Computing, 24(4), 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefalidou, G. (2017). When immediate interactive feedback boosts optimization problem solving: A ‘human-in-the-loop’ approach for solving capacitated vehicle routing problems. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C. M., & McLaughlin, A. C. (2012). Individual differences in the benefits of feedback for learning. Human Factors, 54(1), 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kippenberger, T. (1997). The prisoner’s dilemma. The Antidote, 2(4), 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokolstov, V. N., & Malafeyev, O. A. (2020). Around the prisoner’s dilemma. In Understanding game theory: Introduction to the analysis of many agent systems with competition and cooperation (pp. 3–28). World Scientific. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, T., Rumyaantseva, M., & Welch, C. (2025). Qualitative restudies: Research designs for retheorizing. Organizational Research Methods, 28(1), 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. F., DeRue, D. S., Karam, E. P., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (2011). The impact of feedback frequency on learning and task performance: Challenging the “more is better” assumption. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 116(2), 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. W., Peng, K. Z., Wong, C.-H., & Lau, D. C. (2017). Is more feedback seeking always better? Leader-member exchange moderates the relationship between feedback-seeking behavior and performance. Journal of Management, 43(7), 2195–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. T. Y., Wong, B. P., Chow, B. W. Y., & McBride-Chang, C. (2006). Predictors of suicide ideation and depression in Hong Kong adolescents: Perceptions of academic and family climates. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(1), 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G. J. M., Knoben, J., & Meeys, M. T. H. (2018). Contradictory yet coherent? Inconsistency in performance feedback and R&D investment change. Journal of Management, 44(2), 658–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakas, G. M., Yi, M. Y., & Johnson, R. D. (1998). The multilevel and multifaceted character of computer self-efficacy: Toward clarification of the construct and an integrative framework for research. Information Systems Research, 9(2), 126–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A. R., Rydell, R. J., & Brown, C. M. (2009). On the experience of self-relevant feedback: How self-concept organization influences affective responses and self-evaluations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriman, K. K. (2017). Extrinsic work values and feedback: Contrary effects for performance and well-being. Human Relations, 70(3), 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiejuk, K., Wasson, B., & Egelandsdal, K. (2021). Using learning analytics to understand student perceptions of peer feedback. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, T. T., & Chang, J. C.-J. (2009). Self-efficacy, overconfidence, and the negative effect on subsequent performance: A field study. Information & Management, 46(2), 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morony, S., Kleitman, S., Lee, Y. P., & Stankov, L. (2013). Predicting achievement: Confidence vs self-efficacy, anxiety, and self-concept in Confucian and European countries. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C. A., Coover, D., & Owen, S. T. (1989). Development and validation of the computer self-efficacy scale. Education & Psychological Measurement, 49(4), 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narciss, S., Sosnovsky, S., Schnaubert, L., Andrès, E., Eichelmann, A., Gogua, G., & Melis, E. (2014). Exploring feedback and student characteristics relevant for personalizing feedback strategies. Computers & Education, 71, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. T., Wright, E. P., Dedding, C., Pham, T. T., & Bunders, J. (2019). Low self-esteem and its association with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in Vietnamese secondary school students: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlikowski, W. J. (2000). Managing use not technology: A view from the trenches. In D. A. Marchand, T. H. Davenport, & T. Dickson (Eds.), Mastering information management (pp. 253–257). Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, R., Benjet, C., Borges, G., Moneta Arce, M. F., Fregoso Ito, D., Fleiz, C., & Villatoro, J. A. (2018). Association between attempted suicide and academic performance indicators among middle and high school students in Mexico: Results from a national survey. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry & Mental Health, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccoli, G., Rodriguez, J., Palese, B., & Bartosiak, M. L. (2020). Feedback at scale: Designing for accurate and timely practical digital skills evaluation. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(2), 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, E., Blau, I., & Barak, A. (2018). Measuring digital literacies: Junior high-school students’ perceived competencies versus actual performance. Computers & Education, 126, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto-Bellini, C. G. (2018). The ABCs of effectiveness in the digital society. Communications of the ACM, 61(7), 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto-Bellini, C. G., & Serpa, M. L. (2018, August 16–18). Mirror, mirror on the wall: An experiment on feedback and overconfidence in computer-mediated tasks. 24th Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Porto-Bellini, C. G., Isoni Filho, M. M., De Moura, P. J., Jr., & Pereira, R. C. F. (2016). Self-efficacy and anxiety of digital natives in face of compulsory computer-mediated tasks: A study about digital capabilities and limitations. Computers in Human Behavior, 59(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto-Bellini, C. G., Pereira, R. C. F., & Becker, J. L. (2020). Emergent customer team performance and effectiveness: An ex-post-facto study on cognition and behavior in enterprise systems implementation. Communications of the AIS, 47, 550–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, A., & Morton, T. A. (2012). Sizing fish and ponds: The joint effects of individual- and group-based feedback. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A. S., Bergen, H. A., Martin, G., Roeger, L., & Allison, S. (2005). Perceived academic performance as an indicator of risk of attempted suicide in young adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research, 9(2), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C. (1989). Competence feedback, task feedback, and intrinsic interest: An examination of process and context. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25(4), 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J., Schmutz, S., Sonderegger, A., & Messerli, N. (2019). Social stress and performance in human-machine interaction: A neglected research field. Ergonomics, 62(11), 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaerer, M., Kern, M., Berger, G., Medvec, V., & Swaab, R. I. (2018). The illusion of transparency in performance appraisals: When and why accuracy motivation explains unintentional feedback inflation. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 144, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A. M., & Deshon, R. P. (2010). The moderating effects of performance ambiguity on the relationship between self-efficacy and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H. (1987). Peer models and children’s behavioral change. Review of Educational Research, 57(2), 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherf, E. N., & Morrison, E. W. (2020). I do not need feedback! Or do I? Self-efficacy, perspective taking, and feedback seeking. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(2), 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T. A., & Kimbal, D. R. (2010). Learning from feedback: Spacing and the delay-retention effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 36(1), 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuillard, S., Adams, M., Jelmini, G., Schmutz, S., Sonderegger, A., & Sauer, J. (2022). When humans and computers induce social stress through negative feedback: Effects on performance and subjective state. Computers in Human Behavior, 133, 107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C. I., Correia, J., Compeau, D., & Carter, M. (2022). Computer self-efficacy: A replication after thirty years. AIS Transactions on Replication Research, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-W. (2013). An effective online teaching method: The combination of collaborative learning with initiation and self-regulation learning with feedback. Behaviour & Information Technology, 32(7), 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, J.-Y. (2009). The impact of general and specific performance and self-efficacy on learning with computer-based concept mapping. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfert-Blank, A.-S., & Schmidt, I. (2022). Assessing digital self-efficacy: Review and scale development. Computers & Education, 191, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger-Aviram, E., Zwikael, O., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2013). Revisiting goals, feedback, recognition, and performance success: The case of project teams. Group & Organization Management, 38(5), 570–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancouver, J. B., & Kendall, L. N. (2006). When self-efficacy negatively relates to motivation and performance in a learning context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., & Williams, A. A. (2001). The changing signs in the relationships among self-efficacy, personal goals, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(4), 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., Tischner, E. C., & Putka, D. J. (2002). Two studies examining the negative effect on self-efficacy on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2016). Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. Journal of the AIS, 17(5), 328–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, C., Driessen, E., Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M., Vanstone, M., & Lingard, L. (2012). Understanding responses to feedback: The potential and limitations of regulatory focus theory. Medical Education, 46(6), 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. (1992). Correcting for acquiescent response bias in the absence of a balanced scale: An application to class consciousness. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(1), 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetherall, K., Robb, K. A., & O’Connor, R. C. (2019). Social rank theory of depression: A systematic review of self-perceptions of social rank and their relationship with depressive symptoms and suicide risk. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246(1), 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G. B., & Neal, A. (2006). An examination of the dynamic relationship between self-efficacy and performance across levels of analysis and levels of specificity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakay, D. (1992). The influence of computerized feedback on overconfidence in knowledge. Behaviour & Information Technology, 11(6), 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingoni, M., & Byron, K. (2017). How beliefs about the self influence perceptions of negative feedback and subsequent effort and learning. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 139, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z., Schunn, C. D., & Wang, Y. (2021). What aspects of online peer feedback robustly predict growth in students’ task performance? Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | GCTRL | GPOS | GNEG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (quantity) | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Second semester participants (%) | 89 | 94 | 89 |

| Average age (years) | 21.8 | 23.7 | 22.7 |

| Average first contact with computers (year) | 2002 | 2000 | 2002 |

| Participants with experience in computer-related industry internship (quantity) | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Participants with computer-related work experience (quantity) | 11 | 8 | 13 |

| Average duration of internship (months) | 7 | 17.5 | 7 |

| Average work experience (months) | 31 | 86 | 51 |

| Female participants (%) | 55 | 72 | 28 |

| Male participants (%) | 45 | 28 | 72 |

| Average importance attributed to computer use for personal issues (0–10) | 8.83 | 8.78 | 8.67 |

| Average importance attributed to computer use for professional issues (0–10) | 9.5 | 8.94 | 9.44 |

| Sequential Action | Code | Duration (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Priming with a video about the prisoner’s dilemma | Priming | 10 |

| Measurement of computer self-efficacy (G-CSE, P-CSE, T-CSE) | CSE1 | 5 |

| Electronic spreadsheet task (first version) | Task #1 | 35 |

| Self-evaluation of performance | SRP1 | * |

| External evaluation of actual performance | ATP1 | ** |

| Feedback intervention | Feedback | *** |

| Measurement of computer self-efficacy (G-CSE, P-CSE, T-CSE) | CSE2 | 5 |

| Electronic spreadsheet task (second version) | Task #2 | 35 |

| Self-evaluation of performance | SRP2 | * |

| External evaluation of actual performance | ATP2 | ** |

| Student (GCTRL) | AvCSE1 | ATP1 | AvCSE1—ATP1 | AvCSE2 | ATP2 | AvCSE2—ATP2 |

| M2 | 9.07 | 5.50 | 3.57 | 9.00 | 7.00 | 2.00 |

| M4 | 4.73 | 5.75 | −1.02 | 6.20 | 6.25 | −0.05 |

| M10 | 4.07 | 2.00 | 2.07 | 4.67 | 4.00 | 0.67 |

| M13 | 2.67 | 3.00 | −0.33 | 3.27 | 3.50 | −0.23 |

| M18 | 7.00 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 3.20 | 4.75 | −1.55 |

| M25 | 9.40 | 7.50 | 1.90 | 9.53 | 6.50 | 3.03 |

| M27 | 5.60 | 5.00 | 0.60 | 5.67 | 5.50 | 0.17 |

| M28 | 9.33 | 6.75 | 2.58 | 8.87 | 8.75 | 0.12 |

| M29 | 5.73 | 3.00 | 2.73 | 5.60 | 3.75 | 1.85 |

| E1 | 6.80 | 5.50 | 1.30 | 6.47 | 7.00 | −0.53 |

| E3 | 7.87 | 7.00 | 0.87 | 8.40 | 8.00 | 0.40 |

| E6 | 5.93 | 5.75 | 0.18 | 8.13 | 6.00 | 2.13 |

| E7 | 5.40 | 5.75 | −0.35 | 3.53 | 5.50 | −1.97 |

| E15 | 8.27 | 6.50 | 1.77 | 7.93 | 6.00 | 1.93 |

| E16 | 8.60 | 7.75 | 0.85 | 9.00 | 9.50 | −0.50 |

| E18 | 4.60 | 6.75 | −2.15 | 4.40 | 8.75 | −4.35 |

| E23 | 8.80 | 8.75 | 0.05 | 9.27 | 9.00 | 0.27 |

| E25 | 3.53 | 4.75 | −1.22 | 2.87 | 5.50 | −2.63 |

| Student (GPOS) | AvCSE1 | ATP1 | AvCSE1—ATP1 | AvCSE2 | ATP2 | AvCSE2—ATP2 |

| M6 | 8.27 | 5.75 | 2.52 | 8.87 | 6.25 | 2.62 |

| M7 | 3.13 | 5.00 | −1.87 | 2.07 | 5.75 | −3.68 |

| M8 | 3.53 | 6.50 | −2.97 | 4.47 | 8.00 | −3.53 |

| M12 | 6.80 | 4.00 | 2.80 | 6.60 | 5.25 | 1.35 |

| M15 | 2.80 | 4.75 | −1.95 | 3.00 | 6.50 | −3.50 |

| M17 | 9.07 | 9.00 | 0.07 | 8.60 | 9.75 | −1.15 |

| M20 | 8.73 | 5.75 | 2.98 | 8.87 | 6.00 | 2.87 |

| M22 | 7.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 7.07 | 7.00 | 0.07 |

| M23 | 0.73 | 4.25 | −3.52 | 1.73 | 5.25 | −3.52 |

| M24 | 7.67 | 7.25 | 0.42 | 7.87 | 7.50 | 0.37 |

| E2 | 4.67 | 6.00 | −1.33 | 4.47 | 6.75 | −2.28 |

| E4 | 6.33 | 6.00 | 0.33 | 6.07 | 8.00 | −1.93 |

| E10 | 5.07 | 3.75 | 1.32 | 6.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 |

| E11 | 5.33 | 6.50 | −1.17 | 6.07 | 7.75 | −1.68 |

| E12 | 3.80 | 4.00 | −0.20 | 3.07 | 3.50 | −0.43 |

| E14 | 6.07 | 7.50 | −1.43 | 6.73 | 7.75 | −1.02 |

| E20 | 9.33 | 4.00 | 5.33 | 8.87 | 9.25 | −0.38 |

| E24 | 4.67 | 5.25 | −0.58 | 5.27 | 6.25 | −0.98 |

| Student (GNEG) | AvCSE1 | ATP1 | AvCSE1—ATP1 | AvCSE2 | ATP2 | AvCSE2—ATP2 |

| M9 | 9.33 | 5.25 | 4.08 | 10.00 | − | − |

| M1 | 7.27 | 7.75 | −0.48 | 7.20 | 8.25 | −1.05 |

| M3 | 8.73 | 6.50 | 2.23 | 8.53 | 7.75 | 0.78 |

| M5 | 7.87 | 5.00 | 2.87 | 7.47 | 4.50 | 2.97 |

| M11 | 8.47 | 5.00 | 3.47 | 7.20 | 7.50 | −0.30 |

| M14 | 6.07 | 6.00 | 0.07 | 5.60 | 5.50 | 0.10 |

| M16 | 5.13 | 6.25 | −1.12 | 4.60 | 6.00 | −1.40 |

| M19 | 8.60 | 7.25 | 1.35 | 8.20 | 9.50 | −1.30 |

| M21 | 6.53 | 8.25 | −1.72 | 6.80 | 8.75 | −1.95 |

| M26 | 2.73 | 4.75 | −2.02 | 2.67 | 6.25 | −3.58 |

| E5 | 8.60 | 7.00 | 1.60 | 8.60 | 8.25 | 0.35 |

| E8 | 7.20 | 4.75 | 2.45 | 3.93 | 4.75 | −0.82 |

| E9 | 8.00 | 5.50 | 2.50 | 5.93 | 5.75 | 0.18 |

| E13 | 5.87 | 1.75 | 4.12 | 3.33 | 1.00 | 2.33 |

| E17 | 9.00 | 6.50 | 2.50 | 8.33 | 7.75 | 0.58 |

| E19 | 5.53 | 3.00 | 2.53 | 4.13 | 6.50 | −2.37 |

| E21 | 8.60 | 5.25 | 3.35 | 8.93 | 6.25 | 2.68 |

| E22 | 9.67 | 8.75 | 0.92 | 9.53 | 8.50 | 1.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Porto-Bellini, C.G.; Serpa, M.L.; Pereira, R.d.C.d.F. Computer Self-Efficacy and Reactions to Feedback: Reopening the Debate in an Interpretive Experiment with Overconfident Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040511

Porto-Bellini CG, Serpa ML, Pereira RdCdF. Computer Self-Efficacy and Reactions to Feedback: Reopening the Debate in an Interpretive Experiment with Overconfident Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040511

Chicago/Turabian StylePorto-Bellini, Carlo G., Malu Lacet Serpa, and Rita de Cássia de Faria Pereira. 2025. "Computer Self-Efficacy and Reactions to Feedback: Reopening the Debate in an Interpretive Experiment with Overconfident Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040511

APA StylePorto-Bellini, C. G., Serpa, M. L., & Pereira, R. d. C. d. F. (2025). Computer Self-Efficacy and Reactions to Feedback: Reopening the Debate in an Interpretive Experiment with Overconfident Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040511