Abstract

The impostor phenomenon, characterized by self-doubt and an external attribution of success, significantly impacts daycare center directors, influencing their leadership effectiveness and childcare quality. This qualitative study aims to explore how the impostor phenomenon manifests among Korean daycare center directors within an ecological framework. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 Korean daycare center directors using grounded theory methods. Analysis identified the phenomenon across cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions, revealing both negative self-perceptions and strategic, perfectionism-related behaviors consistent with previous research. This study proposes a contextual model based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, illustrating interactions at macrosystem, exosystem, mesosystem, microsystem, and chronosystem levels, with a detailed paradigm model further explaining microsystem and chronosystem interactions. These findings contribute to clarifying and contextualizing the impostor phenomenon, particularly highlighting situational influences and strategic manifestations. This research provides a foundation for future studies in South Korean contexts and practical insights for developing targeted leadership support programs for daycare center directors.

1. Introduction

Owing to rapid economic growth, fierce competitiveness and hierarchy have become deeply entrenched in Korean society. In South Korea’s hierarchical society, psychological pressure is further exacerbated when individuals feel that their performance is not sufficiently recognized, with those in leadership positions experiencing the impostor phenomenon more strongly (Y. S. Choi & Choi, 2020; Rohrmann et al., 2016). The impostor phenomenon is a psychological condition in which individuals persistently doubt their abilities and attribute success to external factors (Clance & Imes, 1978). It is associated with increased depression, anxiety, burnout, and job dissatisfaction (McGregor et al., 2008; Vergauwe et al., 2015) and is particularly common among high-achieving women (Clance & Imes, 1978). This may be even more pronounced in female-dominated occupations. According to the Seoul Metropolitan Government (2023), childcare center directors are overwhelmingly women, with 4346 (98.3%) compared to 74 (1.7%) men.

Although previous research on the impostor phenomenon has been conducted extensively in Western contexts including North America and Europe, studies in some Asian countries remain relatively fewer. These Western studies have primarily focused on specific professional populations, such as those in medicine (LaDonna et al., 2018; Chodoff et al., 2023; Chakraverty, 2024b), engineering (Maji, 2021; Chakraverty, 2021, 2022, 2024a), and among doctoral students (Cope-Watson & Betts, 2010; Cisco, 2020). In East Asia, a few studies have begun to explore this phenomenon. For instance, in China, Xu (2020) examined the relationship between implicit intelligence and impostor feelings among adolescents, while Liu et al. (2023) investigated the mediating role of impostor experiences between perfectionism and depression in college students.

In South Korea, however, empirical research on the impostor phenomenon remains scarce. To date, only a small number of quantitative studies have been conducted—for example, G. Y. Kim and Lee (2023) focused on athletes, and Byun (2024) examined female university faculty members, both using the term “impostor syndrome”. Notably, there is no prior research specifically addressing the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors. Existing qualitative studies on daycare center directors in Korea have instead explored different topics, such as institutional challenges (Cha & Kwon, 2011; E. J. Lee & Park, 2018; Kang et al., 2019; M. K. Yoon & Bae, 2021) and leadership-related concerns (Cho, 2011; Oh, 2012; H. J. Yoon & Heo, 2012).

Feenstra et al. (2020) argued that instead of viewing impostorism as a personality trait, it is crucial to explore ways to reduce impostor emotions by identifying the social and contextual factors that influence it. Building on this perspective, Tewfik et al. (2025) emphasize the importance of clarifying the conceptual core of the impostor phenomenon—particularly the cognitive belief that others have an inflated view of one’s competence—while also distinguishing between enduring trait-like tendencies and situationally triggered impostor experiences. Leonhardt et al. (2017) further contribute to this nuanced understanding by distinguishing between internalized impostor feelings and more performative, strategic expressions of self-doubt, which may be driven by social expectations or impression management goals. These insights underscore the need to explore how impostor feelings emerge in relation to professional context, cultural expectations, and personal disposition.

Therefore, the primary purpose of this study is to explore the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors and to develop a contextual model grounded in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. This model illustrates how the phenomenon unfolds across multiple levels—including the macrosystem, exosystem, mesosystem, microsystem, and chronosystem. In particular, the paradigm model developed in this study explicates dynamics within the microsystem and chronosystem, serving as an analytical component that complements the broader contextual framework.

Directors in Korean daycare centers frequently navigate complex relationships with parents, whose expectations and communication styles may shape the directors’ sense of leadership efficacy. These relational and contextual pressures can interact with internalized self-doubt and contribute to the manifestation of the impostor phenomenon.

To investigate this, the study seeks not only to examine how the impostor phenomenon is experienced by Korean daycare center directors, but also to construct a contextual model that captures the socio-ecological dimensions of these experiences.

The research questions of this study are as follows:

- How does the impostor phenomenon manifest among Korean daycare center directors?

- How can the contextual model of the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors be described?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach

This study employed a combination of Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) systematic grounded theory and Bowers and Schatzman’s (2016) dimensional analysis to examine the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors. Systematic grounded theory, a specific approach within grounded theory methodology, provides a structured framework for exploring and explaining the subjective meanings individuals assign to their experiences and the processes through which these meanings emerge (Creswell, 2017). Dimensional analysis, on the other hand, is an independent methodological approach rooted in grounded theory that focuses on identifying the multidimensional nature of a phenomenon and examining the contextual relationships among its core dimensions (Carlin & Kim, 2019). By integrating these two methodologies, this study analyzed the subjective meanings experienced by directors and explored how the impostor phenomenon manifests and evolves in diverse social and psychological contexts. This combined approach enabled a deeper explanation of the emergent processes and the complex structure underlying the impostor phenomenon, providing a clearer understanding of its meaning in relation to the directors’ lived experiences.

In addition, this study adopted a spiral model of analysis, which allowed categories and theoretical frameworks to evolve through continuous engagement with the data. As the data collection and coding progressed, preliminary categories were revisited and refined in response to new insights, allowing theory and interpretation to co-evolve throughout the research process (Cohen et al., 2017). This recursive engagement between data and emerging theory enhanced both the depth and rigor of the analysis.

2.2. Participants

This study included 15 Korean daycare center directors, all of whom were female (Table 1). Participants ranged in age from 41 to 61 years, with between 5 and 34 years of experience as directors. Given the study’s focus on internalized professional experiences, it was essential to ensure that participants clearly understood the central phenomenon under investigation.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

The term “impostor phenomenon” was introduced as the main topic of the study, and participants were provided with sufficient explanations through video materials and verbal briefings prior to the interviews to ensure a clear and consistent understanding of the concept. The video content included a definition of the impostor phenomenon, along with contextualized examples relevant to Korean society. Only individuals who acknowledged having experienced the impostor phenomenon in the course of their professional roles participated in the interviews. This selection criterion ensured that the data collected accurately reflected participants’ lived experiences and contributed to a deeper understanding of how the impostor phenomenon unfolds within specific social and cultural contexts.

2.3. Ethical Issues

This study was conducted with full consideration of participants’ ethical rights and was approved by redacted. Prior to the interviews, the purpose and procedures of the study were explained to the participants, including assurances of confidentiality regarding personal information and interview contents. Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before interviews. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. All interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ explicit consent, and key transcripts were reviewed for analysis.

2.4. Procedure and Analysis

We collected data through face-to-face interviews with the participants, each lasting approximately 60 min. One or two follow-up interviews were conducted at a later date, supplemented by additional non-face-to-face interviews conducted via phone or online.

The interviews were transcribed using CLOVA Note, an automated speech-to-text tool, resulting in approximately 156 pages of transcriptions. These data were analyzed through iterative coding and review. Using Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) systematic grounded theory approach, an inductive qualitative research method, we developed an exploratory model based on empirical data. The analysis followed a three-step coding procedure—open coding, axial coding, and selective coding—to identify major categories and subcategories that explain how the impostor phenomenon manifests among Korean daycare center directors.

In the first step, open coding was conducted, involving line-by-line analysis to generate concepts closely aligned with the data. During this process, memos were drafted to organize and structure the analysis, leading to the identification of axes for further exploration. In the second step, axial coding, patterns of actions were categorized by linking the conditions and consequences of the concepts through constant comparison. Theoretical memos further refined these axes, resulting in the emergence of a core category. In the final step, selective coding ensured consistency and coherence in the analysis. This structured, multi-phase approach facilitated a comprehensive interpretation of participants’ experiences and strengthened the analytic rigor of the study (Morse, 2000).

In parallel, the study employed dimensional analysis to explore the phenomenon’s multidimensional nature within the ecological systems framework. Dimensional analysis, an independent methodological approach rooted in grounded theory, focuses on how phenomena are contextually constructed through various dimensions. This lens allowed us to examine how the impostor phenomenon develops through interactions across ecological layers, from institutional to interpersonal. The resulting contextual model illustrates how ecological factors contribute to the emergence and trajectory of impostor emotions in daycare center leadership.

Finally, the study adopted a spiral model of analysis to synthesize findings from both the literature review and interview data. An initial theoretical framework was established based on prior literature, which was subsequently refined through data-driven analysis. This iterative process of revisiting and adjusting theory ensured an increasing theoretical alignment and depth over time (Bryman, 2016). The dynamic interaction between the literature, data, and emerging interpretations enhanced the overall completeness and credibility of the findings.

3. Results

To investigate the manifestation of the impostor phenomenon as experienced by Korean daycare center directors, the collected data were continually compared and analyzed to group similar concepts. The categorization results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Concepts, subcategories, and categories derived from the interviews.

To better reflect the multifaceted experiences described by participants, the findings are presented across cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions. This structure facilitates clarity while capturing both self-doubting and strategically adaptive responses.

3.1. Open Coding

- Mental health

Korean daycare center directors reported feeling discouraged when their efforts were unrecognized by parents and experiencing internal conflict when they questioned their suitability for their role as directors. Similarly, individuals experiencing the impostor phenomenon often struggle with depression, anxiety, and lethargy when they feel their efforts fall short of expectations or when they question their qualifications (McGregor et al., 2008).

- Despondency

“Sometimes I get angry and upset when I have worked hard and been sensitive to safety issues in childcare all day and the parent does not acknowledge it, especially when I have to admit I did something wrong where I did not do anything wrong”.(D3)

- Internal conflict about the job

“It makes you think, “Oh, this is not working, even though I am working so hard”, and now sometimes you have one too many negative experiences with parents that make you rethink this business”.(D1)

- Personality

Directors with perfectionist personalities showed varied work performance and stress levels, which was linked to the impostor phenomenon. This connection aligns with findings by D. Yoon (2022), who stated that perfectionism can be categorized into four types: avoidant, supervisory, self-blaming, and stable. In this study, the directors exhibited supervisory, self-blaming, and stable forms of perfectionism. Supervisory perfectionists impose their high standards on others, which can cause stress to those around them, whereas self-blaming perfectionists value other people’s standards more than their own and tend to focus on outcomes rather than the process. In contrast, stable perfectionists selectively pursue perfection in essential tasks, utilizing the positive aspects of perfectionism without fearing mistakes or failures.

- Perfectionist personality

Supervisory perfectionists excessively interfered with teachers’ work to bring it up to their own standards, which resulted in the common anxiety and self-doubt associated with the impostor phenomenon, as they viewed the failure to meet these high standards as evidence of a lack of competence.

“I am not just perfect for myself, I am perfect for others, and I think that is why the teachers here are more meticulous and detailed and good at it. I did not know it, but I think I am the kind of person who imposes what is in me on others”.(D10)

Self-blaming perfectionists struggled to accept their imperfections, became overly sensitive to parents’ judgment, and excessively criticized themselves. This was closely related to the impostor phenomenon, as they frequently doubted their qualities and judged themselves harshly.

“I am a perfectionist, and I go back over my mistakes to make sure they do not cause any damage, so I do not sleep well at night during events”.(D8)

In contrast, stable perfectionist principals are able to reduce both their own stress and that of the teachers by pursuing perfection only in important tasks, thus alleviating anxiety related to the impostor phenomenon.

“When I do the paperwork, I try to do it perfectly, but I think I try not to do it too perfectly because if I do it perfectly, how hard is it going to be for everyone else?”(D6)

- Personal beliefs

Finally, directors set expectations for their roles based on their beliefs about needing to prove their expertise as education experts or as executives for managing budgets efficiently in running a daycare center. Psychological pressure tends to intensify when their performance falls short of these expectations.

- Beliefs as an education expert

“I would like to see an objective evaluation of the word expert, not in terms of years, but in terms of actual skill. I have been an expert for decades. But if I cannot show that when I ask myself, ‘What do you know how to do?’ then I think I am not an expert”.(D2)

- Beliefs as an executive

“I consider myself more of an operator than an educator, as I have been a director for much longer. I see myself as an entrepreneurial director, essentially a businessman, responsible for recruiting children and managing finances. For instance, if the income is 100, I need to allocate percentages from that amount, assess the value provided to the children, and evaluate the effectiveness of that value. It is not just about how much money I make but also about ensuring the value I gain aligns with the work I put in”.(D7)

- Sociocultural characteristics of South Korea

Korean daycare center directors face significant pressure from parents’ expectations to manage daycare centers in this highly competitive environment. This heightened pressure stems from South Korea’s ultra-low birthrate and reinforces the tendency for parents to invest heavily in a single child to ensure their success in an increasingly competitive society (J. W. Lee et al., 2018).

- Daycare center management challenges in Korean society

In this study, directors raised in a traditional Confucian society with collectivistic tendencies experienced conflicts arising from the individualistic tendencies of the parents, who are also their children’s peers. According to U. Kim (2006), South Korea was historically a collectivist society that prioritized the stability and interests of groups, such as the family and state, over the individual until the end of the 19th century. This was largely due to the influence of Confucian culture, which valued group harmony above individual interests. However, with the introduction of Western democracy and industrialization in the early 20th century, individualism, emphasizing individual autonomy and rights independent of group needs, began to spread (U. Kim, 2006). S. W. Yoon (2016) also noted that South Korea’s rapid economic growth has created a society where several ideologies coexist, including meritocracy, which fosters competition, and authoritarianism, which emphasizes hierarchy.

“It is stressful because we are constantly competing and we are constantly having to surface the things that we are doing well, and it is a social atmosphere”.(D13)

“I do not think there should be individualism when looking at children, but nowadays, parents are too individualistic, so it is difficult for institutions to live in a group”.(D6)

Additionally, this study found that growing up in this traditional Confucian society led to the development of introverted and principled personalities. Shin and Jeong (2002) further highlighted that traditional Korean society is rooted in an authoritarian culture based on Confucian values, which has reinforced patriarchy and hierarchy. These Confucian traditions have entrenched power structures within society, with absolute respect for paternal authority in the family and hierarchical relationships between teachers and students in education.

“My dad was a teacher, so I grew up getting beaten up a lot, and it really affected my character and my self-esteem, so I do not like to be in front of anybody, and I am very shy”.(D4)

- Policy

- Frequent curriculum changes

Daycare center directors continued to face challenges in implementing a play-based curriculum, particularly due to parental misunderstandings about the nature of learning through play. The “Nuri Curriculum for Ages Three to Five”, implemented in March 2013, was criticized for limiting toddlers’ opportunities to play by adopting teacher-centered teaching methods (Lim, 2017). In response, the play-centered curriculum, introduced in March 2020, focuses on toddler-led learning through play, emphasizing child agency in the learning process (Ministry of Education & Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2019). However, according to E. Y. Kim et al. (2020), while parents recognized the value of a play-centered curriculum, they expressed concerns that their children might simply play at daycare centers and face difficulties adapting to elementary school.

“It is hard to put play-centeredness into practice, it is very hard, but you have to do it, so you have to tell the teachers, you know, this is wrong, this is how it should be done, this is how it should be done, but then when you are in the field, it does not go the way it should go in theory, so I think that is the hardest part”.(D4)

“I think the process of applying play-centeredness makes you think a lot about whether it looks like you are just playing to the parents, or whether it looks like you are not interested in the child”.(D1)

- Impostor phenomenon cognitive aspects

In this study, directors blamed themselves for poor counseling and conflict resolution skills in their relationships with parents, underestimated their abilities as directors, and attributed their success to luck or external factors. This tendency aligns with findings on the impostor phenomenon, where individuals often attribute their achievements to external factors or luck rather than taking credit for them (McGregor et al., 2008).

- Self-devaluation

“I think if I would have looked at it a little bit more, if I would have coached the teachers a little bit more when the parents were point, and I think there is also a sense of self-blame now that we are problem solving, when signing the teachers like this, we would not have gotten to this end there’s a complaint like that, when we are solving this, it would be nice if it worked out, but when it does not, it is because I am not good enough”.(D14)

- Luck

“When I hear positive things about me from parents, I actually look at myself and think to myself that maybe they are giving me too much credit because I did not do enough to deserve it”.(D7)

- Impostor phenomenon emotional aspects

In this study, directors experienced emotional withdrawal due to perceived inadequacies in handling situations with parents, which led to low self-esteem. Furthermore, they faced emotional exhaustion stemming from conflicts in their relationships with parents and exhaustion from taking on extroverted roles that conflicted with their introverted personalities. Research has shown a strong link between the impostor phenomenon and low self-esteem (Chrisman et al., 1995), as well as its association with excessive stress and emotional burnout (Hutchins & Rainbolt, 2017).

- Low self-esteem

“I feel like I lose my self-esteem when I feel like I am not good enough, and I feel like I am not good enough to cope like this”.(D10)

- Emotional exhaustion

“I am usually an introvert, but when I am at the daycare center, I become more socially active. During events or when parents come to visit, there are tasks that I need to take the lead on. After handling those, I feel emotionally drained when I get home”.(D15)

- Impostor phenomenon behavioral aspects

In this study, directors worked tirelessly to mask their perceived lack of competence during parent counseling sessions, which led to excessive complaint handling and over-preparation for meetings with parents. They also maintained an outwardly confident demeanor while concealing their inner insecurities. This aligns with Ferrari and Thompson’s (2006) findings that individuals with impostor syndrome often hide their anxiety behind a façade of confidence.

- Overwork

“Especially with parents, I am worried about revealing my ignorance to them, so I end up staying up all night looking for resources, studying, and dealing with parents before the consultation. When dealing with parents, I feel like I have to keep proving and showing them that we are different. I double- and triple-check what the teachers have done to make sure I do not miss any details”.(D1)

- Fake

“I think I have a little bit of a timid side to me, and sometimes I get intimidated if I am not ready or if someone’s doing a better job than I am, and you cannot do that with parents, and I am supposed to be the one talking and leading, so I think I am just trying to make myself look good in my head”.(D9)

- Individual effort

As they experienced the impostor phenomenon in their relationships with parents, the directors also sought self-improvement, such as by attending graduate school to increase their theoretical expertise or undergoing training to complement their skills. They also engaged in leisure activities such as traveling, exercising, and reading to relieve stress from their work, and found emotional comfort in religious activities to restore their psychological well-being. These efforts reflect directors’ attempts to overcome feelings of inadequacy and regain a sense of competence.

- Self-development

“I started my master’s because I was afraid of falling behind others and because of what my parents thought of me. I am a business major, so I always feel like I am lacking in my education”.(D1)

“I am learning Instagram, I am learning Excel, I am learning PPT, I am learning how to make videos”.(D8)

- Leisure and hobbies

“I de-stress by going to the mountains or playing golf, or I will watch a really good show for 10 h without thinking about anything, because there is nothing I can do about it, and it is only going to get better with time”.(D11)

- Religious life

“I think that is what gives me the strength to get through the hard stuff, because I am a Christian, I pray, I go to church, I cry, and then I pick myself up and get back on my feet”.(D10)

- Social support

Emotional support from close people was also an important intervening condition.

- Peer director

In terms of relationships with peer directors, some directors who passively participated in activities felt intimidated when their abilities were compared with those of their peers. However, directors who had close relationships and actively communicated with their peers received emotional support and professional help to alleviate their job stress.

“The directors have similar experiences with parents, so we talk to each other when we are upset and get advice when we are struggling, and I think it is great to get wisdom”.(D4)

- Family

In terms of family relationships, some principals gained emotional support by communicating with their spouses and children, which helped mitigate the impostor effect.

“I talk to him a lot, and I am just like, today was like this, today was like that, and now I am just talking about how hard it was for me because of him, and he is just kind of talking from my side, from my teacher’s side, from our daycare center’s side, and he is kind of like, it is not your fault, it is just that he’s weird, and then I am running it, and I am like, this is not working, this is hard, and then he’s like, he will do this, and then he will do that, and then I am kind of relying on him a lot”.(D5)

- Differences in demand stability for daycare centers

The stability of demand at daycare centers also played a crucial role. Directors with stable enrollment, either due to new apartment buildings nearby or the institution’s management strategy, felt comfortable in their relationships with parents and experienced less of the impostor phenomenon. In contrast, the impostor phenomenon was intensified in centers experiencing difficulty in recruiting children because of competition.

- High-demand organizations

“Because it is a new complex, we have so many people coming in from outside, I do not think we’ll have a problem recruiting for the next few years”.(D7)

- Low-demand organizations

“It is the second half of the year, so we have to prepare for kindergarten recruitment, and the situation we are in right now is that there is a big kindergarten with 300 students around us, so there is a lot of things that we cannot do because we are a small childcare center. I think there is anxiety and discomfort because of those things”.(D13)

- Regional differences

- The difference between old and new cities

Finally, regional differences also contributed to the impostor phenomenon. Many more experienced directors had moved more than once; as a result, they became aware of the differences in educational expectations and needs between older and newer urban parents. In particular, they had difficulty adapting to parents in newer cities with higher educational expectations and demands. However, over time, they gradually adapted as they understood the needs of parents and found appropriate strategies, thus gradually easing the impostor phenomenon.

“Where I was before, it was actually not a big deal as long as there was trust, but when I came to this new apartment complex, there is a lot of superiority here. There is a lot of, ‘I want you to do this for me because I want my child to be this big.’”(D7)

“I think when you get a new apartment and you move in, it takes a little bit of time to adjust. I think the way parents treat teachers or daycare centers, I think that level gets less and less over the years, and you get better and better at accepting a lot of demands”.(D15)

- Cognitive changes

Directors who experienced the impostor phenomenon underwent a cognitive shift characterized by pursuing a renewed sense of intrinsic motivation and emphasizing internal happiness and self-worth over material success. This shift helped them overcome the imposter syndrome by relieving the pressure they felt in their relationships with parents and shifting their thinking to recognizing their own efforts and value.

- Pursuing intrinsic motivation

“Success used to be my most important goal, but nowadays, I have come to value my happiness more than success, which has freed me up to enjoy the here and now”.(D11)

- Change in value

“You’re like, ‘I gave you my best and you cannot accept it, so there is nothing more I can do for you, and that is your fault, and I am not ashamed of that at all,’ and if you perceive me that way even though I gave you my best, I am like, ‘Well, I’m just going to keep working hard and maybe someone else will.’ It is changed a lot”.(D4)

- Emotional changes

- The courage of self-acknowledgment

The directors also experienced an emotional transformation, having the courage to acknowledge their imperfections and accept themselves as they were. This helped them find emotional stability in the process of overcoming the impostor phenomenon, reducing their anxiety and fear regarding their role as directors in their relationships with parents.

“But now I am just like, there might be some things that I am not good at and I just accept that and I just do the best that I can and I am just like, I am not going to be the best at anything right now, but I am going to gain experience and I am going to be happy with that, and I think that is a lot easier for me”.(D4)

- Behavioral changes

- Pursuing work–life balance

Lastly, directors exhibited a behavioral shift toward work–life balance. Previously, they had worked excessively to meet parental expectations but now strive to balance their personal and professional lives. This shift helped directors overcome the impostor phenomenon and fulfill their roles as directors in a healthier way.

“I try to take breaks when I am having a hard time so that I can work long hours, and I try to be really good at de-escalating my work, and I think home is just as important as work, so I try not to bring that stress home until the weekend”.(D6)

- Impostor phenomenon persists

- Maintaining impostor phenomenon

Some directors who experienced the impostor phenomenon still felt overwhelmed by increasing responsibilities as they progressed in their careers and continued to put on a confident outward appearance. They remained constantly aware of negative parental evaluations, which kept them on the edge.

“The more experience I have, the more responsibility I have, and I think the more positions and situations I’m in, the more I try to hide myself and put on a good face”.(D10)

“I do not think it is gotten any less nerve-wracking. It is not that it’s easy when you are dealing with parents endlessly, but it is still the same nervousness of what is this person going to think of me, what is this person going to think of our circle, what is this person going to say when they go out and talk to people”.(D14)

- Reduced impostor phenomenon

In contrast, some directors found psychological relief from being judged by others, and the impostor phenomenon was mitigated by recognizing their own efforts and value.

“I feel like I have a strong tendency to try to impress others, but these days I am trying to just be myself and express myself, and I think that is much more authentic and natural”.(D12)

According to the interview data, Korean daycare center directors experience a range of psychological and contextual challenges, often manifesting as feelings of inadequacy, internal conflict, and stress. These experiences are closely connected to the impostor phenomenon, which appears across cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions. Contributing factors include perfectionist tendencies, internalized beliefs about their professional roles, sociocultural expectations rooted in Korean society, and frequent changes in the educational curriculum. While some of these experiences may reflect deeply internalized impostor feelings, others—particularly perfectionism-driven overwork or role enactment—may be better understood as strategic adaptations to professional norms and parental expectations.

Despite these challenges, some directors strive for self-development and seek emotional support from fellow directors or family members to maintain psychological stability. In addition, variations in regional and institutional contexts lead to differences in how the impostor phenomenon is experienced. Notably, while some directors undergo positive cognitive, emotional, and behavioral changes that help them overcome the impostor phenomenon, others continue to be affected by these feelings over time. To more clearly explain the relationships between these categories and to gain a deeper understanding of how the impostor phenomenon is experienced and navigated, the following section presents an analysis based on the paradigm model proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1998).

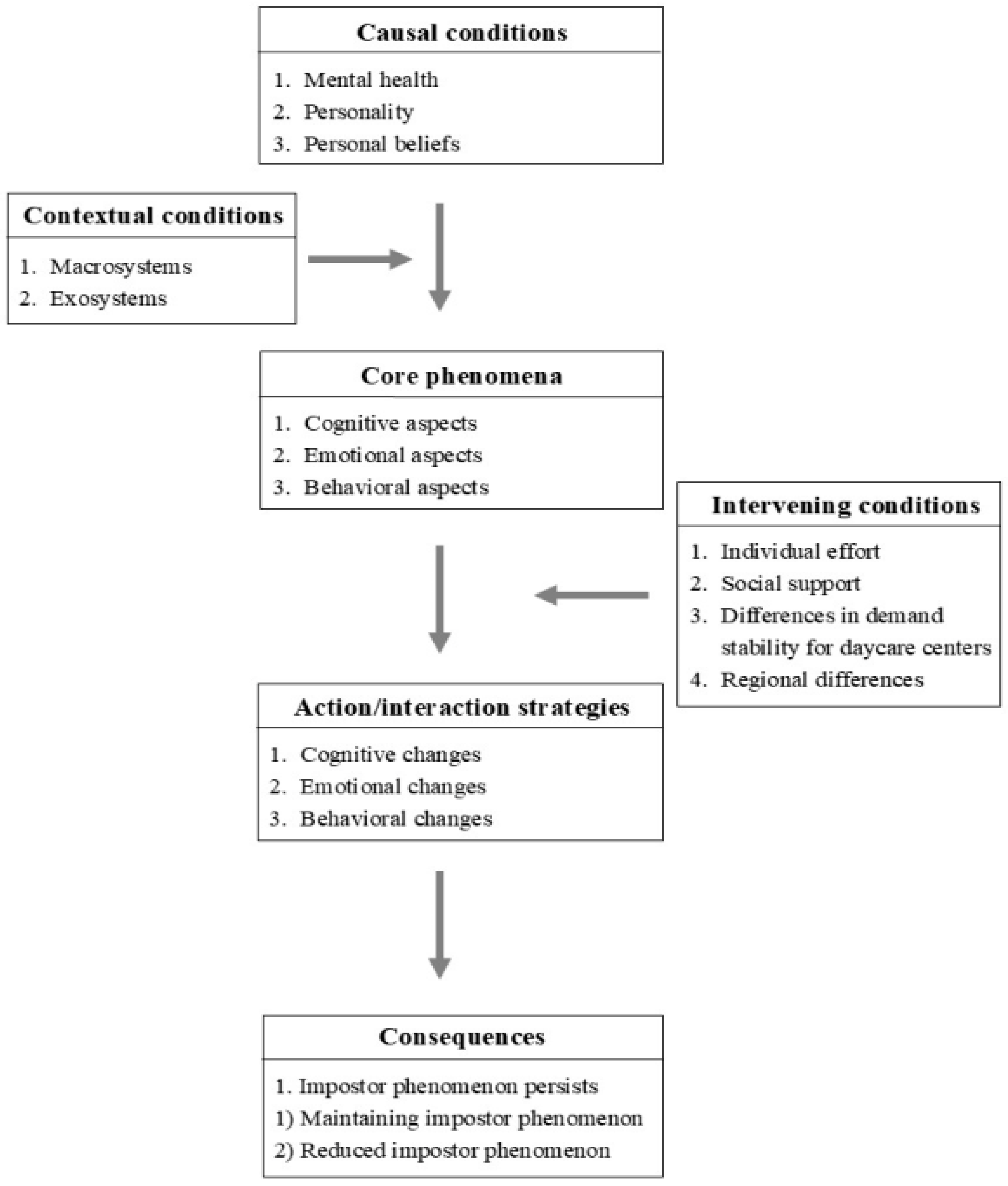

3.2. Paradigm Model

Strauss and Corbin (1998) proposed a paradigm model centered on a core phenomenon and encompassing causal conditions, contextual conditions, intervening conditions, action/interaction strategies, and consequences. Based on this, connections between the categories were established, as shown in Figure 1. In this study, the paradigm model particularly informs an analysis of microsystem-level stressors and time-based developmental changes—functioning as a dynamic component of the broader contextual model.

Figure 1.

A paradigm model of the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors.

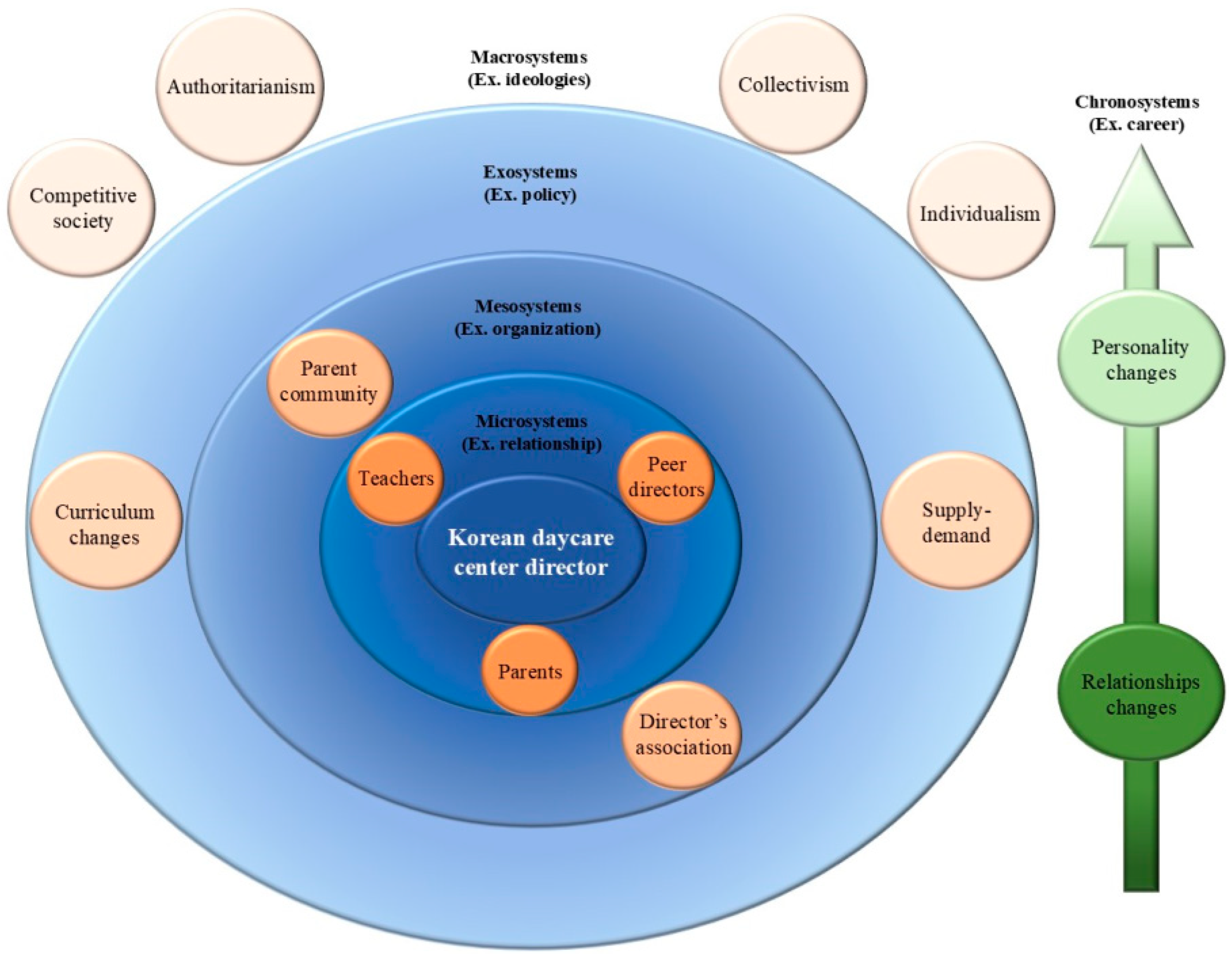

3.3. Contextual Model

In the preceding section, the impostor phenomenon experienced by daycare center directors was analyzed using the paradigm model proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1998). To better reflect the complex and multilayered nature of the phenomenon, this study emphasizes the use of a contextual model. This model serves as the primary framework for analyzing how the impostor phenomenon manifests across various ecological levels (Figure 2) derived through dimensional analysis, as proposed by Bowers and Schatzman (2016). This approach enabled a systematic exploration of the multiple domains influencing directors’ experiences and interpretations of the impostor phenomenon.

Figure 2.

A contextual model of the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors.

The contextual model of the impostor phenomenon experienced by Korean daycare center directors (Figure 2) is based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (1994). The model includes “macrosystems”, “exosystems”, “mesosystems”, “microsystems”, and “chronosystems”, each of which acts as a factor that compounds and reinforces the impostor phenomenon experienced by the directors.

Among these, the microsystem and chronosystem emerged as especially salient in participants’ narratives. The microsystem captures direct interpersonal dynamics—particularly interactions with parents and peers—where internalized self-doubt and strategic behaviors surface. This is consistent with earlier research highlighting how impostor experiences are shaped through immediate social relationships (e.g., Tewfik et al., 2025; Leonhardt et al., 2017). In contrast, the chronosystem represents the developmental trajectory of impostorism, revealing how impostor feelings may intensify or transform over time. These temporal aspects were more directly illuminated through the paradigm model, which captured participants’ reflections on evolving coping strategies and shifting self-perceptions as they gained experience, transitioned roles, and took on greater responsibilities.

The macrosystem indirectly affected the impostor phenomenon by reflecting the sociocultural characteristics of Korean society. South Korea’s sociocultural context is shaped by a blend of Confucian collectivism, rising individualism, and hierarchical values, alongside a strong emphasis on academic and professional success (U. Kim, 2006; S. W. Yoon, 2016). In addition, the country’s ultra-low birthrate has intensified parental investment in their children, increasing expectations on early childhood education settings (J. W. Lee et al., 2018). The macrosystem in this model represents a competitive society in which authoritarianism, collectivism, and individualism stemming from Confucian culture coexist and interact. This sociocultural context reinforces the impostor phenomenon, as directors experience an increased conflict and stress in their relationship with parents, feeling unworthy. These dynamics are further complicated by Korea’s strong face-saving norms, which discourage public displays of uncertainty and reinforce pressure to appear competent (N. Y. Choi & Miller, 2014).

The exosystem was identified as the play-centered curriculum, a policy-driven curriculum for Korean early childhood education. The Nuri Curriculum, implemented in 2013, faced criticism for its teacher-centered approach that restricted children’s play opportunities (Lim, 2017). In response, a revised play-centered curriculum was introduced in 2020, emphasizing child-led learning and promoting children’s agency in the educational process (Ministry of Education & Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2019). In this study, the directors found it difficult to apply the new curriculum; in particular, they were concerned that parents would misunderstand the meaning of learning through play and see it as mere play. In addition, differences in demand stability due to regional characteristics and institutional management strategies emerged. Directors with a stable enrollment felt comfortable in their relationships with parents, whereas those struggling to recruit children felt pressured.

The mesosystem was represented by the parent communication community (mom café) and the director’s association. In this study, we found that directors who frequently checked mom cafés, a parent communication community, were more concerned and anxious about negative posts or comments from parents, whereas those who did not check them were less affected. Mom cafés are online communities where parents share information and opinions about raising children, often using them to discuss their experiences with daycare centers. According to S. B. Park (2019), posts on mom cafés may contain untrue or exaggerated information, which can quickly spread and damage the reputation of daycare centers. In particular, when parents publicly post complaints or grievances on mom cafés, it can have a serious impact on child enrollment and the recruitment of new children. As a result, directors tend to be cautious and take measures to prevent such situations. Some directors who were not actively involved in the daycare center association felt intimidated by comparisons with their peers. Conversely, directors who had close relationships with their peers and actively communicated with them received emotional support and professional help to alleviate job stress.

The microsystem was represented by relationships with peer directors, teachers, and parents, with whom the director directly interacts. Some directors maintained positive relationships with their peers, while others interacted with them in a more formal or business-like manner. In their relationship with teachers, the director found it difficult to exert authority due to teacher turnover and problematic behaviors. In addition, collectivistic directors tried to build positive relationships with teachers but were frustrated by their individualistic tendencies. In terms of relationships with parents, directors aimed to maintain positive relationships but sometimes treated parents more like customers whose needs needed to be met rather than as collaborators in the care of infants and toddlers.

The chronosystem is represented by changes in the directors’ personalities and relationships over time. The extroverted personalities gradually became more introverted as their responsibilities as directors increased and their relationships were reduced to minimize stress. As the directors’ ability to filter information improved, their relationships became narrower, focusing more on those who could provide quality information than on a broad range of people. These evolving strategies may also reflect a shift from externally oriented impression management toward more intrinsic self-validation—signaling a continuum between strategic impostor responses and internal transformation over time.

4. Discussion

Tewfik et al. (2025) and Leonhardt et al. (2017) emphasize that impostor-like behaviors are not always rooted in internalized self-doubt but may also reflect situationally adaptive strategies or impression management. Drawing on these insights, we interpret some of the participants’ behaviors—such as over-preparation or role-playing confidence—not merely as symptoms of impostorism, but as responses shaped by contextual expectations. This interpretive lens is further supported by the ecological and dimensional frameworks employed in this study.

The purpose of this study was to explore the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors and to present a contextual model that explains how this phenomenon is shaped within multilayered environmental systems.

The results from this study reflect the multifaceted nature of the impostor phenomenon, aligning with prior research that identifies both its negative and adaptive aspects (Tewfik et al., 2025). Jackson (2018) defined the leadership impostor phenomenon as the inability of successful leaders to internalize their achievements, attributing them to luck or external factors while harboring a fear of failure. The cognitive aspects of the impostor phenomenon, where directors devalued themselves and credited success to external factors, support Jackson’s conceptualization. Additionally, this study supports Jackson’s findings on perfectionism by showing that directors with perfectionist tendencies often experienced a heightened psychological pressure.

Feenstra et al. (2020) found that female leaders often experienced emotional burnout and maintained a confident outward demeanor to mask their inner feelings of power insecurity. Similarly, our findings indicate that Korean daycare center directors experienced emotional exhaustion and low self-esteem while simultaneously engaging in masking behaviors—an alignment with previously observed behavioral aspects of the impostor phenomenon. At the same time, consistent with Leonhardt et al.’s (2017) distinction between internalized impostor feelings and strategic self-presentation, some directors’ behaviors—such as over-preparation and image management—can be interpreted not only as symptoms of impostorism but also as deliberate strategies influenced by professional expectations and perfectionist tendencies. These interpretations suggest that the impostor phenomenon may have adaptive dimensions, particularly in the context of leadership, where perfectionism may serve both as a psychological burden and a performance enhancer depending on individual traits and situational demands.

Extending prior work that has focused largely on Western and some Asian contexts, our study confirms the cultural adaptability of the impostor phenomenon by situating it within South Korea’s unique sociocultural context. This underscores the global relevance of impostorism and highlights the impact of national-level sociocultural forces—such as Confucian hierarchical values, educational competitiveness, and parental expectations—on the phenomenon. These structural and cultural elements, reflected in the macrosystem layer of our contextual model, help explain why the impostor phenomenon in Korea may carry more negative emotional weight and stress compared to other contexts. In particular, social norms around face-saving, gendered leadership expectations, and pressures from a low birthrate society reinforce internalized doubts and performance anxiety. Gendered leadership expectations may pressure female directors to uphold idealized standards of authority, while the low birthrate context intensifies parental demands on early childhood institutions. Among these, face-saving norms in particular often function as social imperatives that limit emotional expression and increase the psychological cost of perceived failure (N. Y. Choi & Miller, 2014).

A notable contribution of this study is its tripartite framework, which distinguishes cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of the impostor experience. While earlier studies have often presented fragmented sub-factors such as “luck”, “fake”, and “discount”, this study integrates those under broader psychological dimensions to better clarify the phenomenon, as called for by Tewfik et al. (2025).

Furthermore, this study shows that the impostor phenomenon may evolve over the course of a director’s career. Whereas early-career directors may exhibit overt behavioral masking due to inexperience, later-career directors in this study displayed more internalized cognitive conflicts while maintaining a professional façade. This developmental trajectory aligns with the chronosystem emphasis in our contextual model and suggests that tailored interventions should consider career stage.

Crucially, the ecological model developed in this study contributes to the expanding call for more context-sensitive approaches to impostorism (Feenstra et al., 2020). By applying Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) ecological systems theory, the study situates impostorism within multiple interactive systems—ranging from societal norms (macrosystem) to immediate professional relationships (microsystem) and longitudinal development (chronosystem). The microsystem, in particular, encapsulates peer and parent dynamics that closely align with prior research (Tewfik et al., 2025; Leonhardt et al., 2017), while the chronosystem dimension emphasizes the evolving nature of impostor responses—first surfaced through the paradigm model and elaborated through dimensional analysis.

In this way, the contextual model complements the paradigm model by revealing the ecological layers that frame impostorism and by offering a dynamic perspective on how directors navigate internal doubt and external expectations over time. This approach allows for deeper insights into the psychosocial mechanisms underlying impostorism in leadership roles.

Taken together, these findings offer valuable directions for future research and practice. The nuanced understanding of impostor phenomenon developed here could inform the design of counseling programs, leadership training, and institutional policies to support directors’ psychological well-being and professional development.

5. Conclusions

This study employed a grounded theory approach to explore the impostor phenomenon among Korean daycare center directors, offering an in-depth and context-sensitive understanding of how self-doubt, emotional strain, and strategic behavior unfold within complex social environments. Drawing on ecological systems theory and dimensional analysis, the study presented a contextual model that highlights how the impostor phenomenon is shaped by intersecting psychological, relational, and cultural forces.

By identifying cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of impostorism and mapping them across macro-, exo-, meso-, micro-, and chronosystem layers, this study contributes to a more nuanced conceptualization of the impostor phenomenon. In particular, the chronosystem dimension captured the evolving nature of impostor experiences over time, while the microsystem clarified how everyday interpersonal dynamics reinforce internalized self-doubt or promote resilience.

This research broadens the scope of qualitative inquiry into impostorism and deepens our understanding of its manifestations in South Korean leadership contexts. The findings may inform the development of tailored support systems—such as counseling programs and leadership training—designed to address both the psychological and sociocultural dimensions of impostor experiences in educational and care-related professions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-E.L.; methodology, J.-H.C. and Y.-E.L.; validation, J.-H.C. and Y.-E.L.; formal analysis, J.-H.C. and Y.-E.L.; investigation, J.-H.C.; resources, J.-H.C.; data curation, J.-H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-H.C. and Y.-E.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-E.L.; visualization, J.-H.C.; supervision, Y.-E.L.; project administration, Y.-E.L.; funding acquisition, Y.-E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Gachon University under grant number 202404900001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gachon University (approval code: 1044396-202405-HR-085-01; date of approval: 3 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bowers, B., & Schatzman, L. (2016). Dimensional analysis. In Developing grounded theory (pp. 86–126). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. International Encyclopedia of Education, 3(2), 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford university press. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, S. Y. (2024). Exploring the impostor phenomenon among female faculty members in Korean universities. Korean Journal of Teacher Education, 41(1), 333–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, A. P., & Kim, Y. (2019). Teaching qualitative research: Versions of grounded theory. The Grounded Theory Review, 18(1), 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Y. S., & Kwon, M. R. (2011). The difficulties and efforts to solve in managing private child-care institute. Journal of Ecological Early Childhood Education, 10(3), 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraverty, D. (2021). Impostor phenomenon among engineering education researchers: An exploratory study. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 16, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraverty, D. (2022). A cultural impostor? Native American experiences of impostor phenomenon in STEM. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 21(1), ar15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraverty, D. (2024a). Impostor phenomenon in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. In K. Cokley (Ed.), The impostor phenomenon: Psychological research, theory, and interventions (pp. 221–243). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraverty, D. (2024b). Workplace violence and the impostor phenomenon in medicine: A US-based qualitative study. Violence and Gender, 11(2), 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, W. J. (2011). The director’s perception about the characteristic of leadership, and the conflict with leadership in kindergartens and day-care centers. Journal of Childcare Support Research, 6(2), 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodoff, A., Conyers, L., Wright, S., & Levine, R. (2023). “I never should have been a doctor”: A qualitative study of imposter phenomenon among internal medicine residents. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N. Y., & Miller, M. J. (2014). AAPI college students’ willingness to seek counseling: The role of culture, stigma, and attitudes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(3), 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. S., & Choi, C. Y. (2020). Perceptions on the quality of society and life satisfaction in Korea. Korean Social Policy, 27(3), 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrisman, S. M., Pieper, W. A., Clance, P. R., Holland, C. L., & Glickauf-Hughes, C. (1995). Validation of the clance imposter phenomenon scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(3), 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisco, J. (2020). Using academic skill set interventions to reduce impostor phenomenon feelings in postgraduate students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(3), 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope-Watson, G., & Betts, A. S. (2010). Confronting otherness: An e-conversation between doctoral students living with the imposter syndrome. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education/Revue Canadienne des Jeunes Chercheures et Chercheurs en Éducation, 3(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra, S., Begeny, C. T., Ryan, M. K., Rink, F. A., Stoker, J. I., & Jordan, J. (2020). Contextualizing the impostor “syndrome”. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 575024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, J. R., & Thompson, T. (2006). Impostor fears: Links with self-presentational concerns and self-handicapping behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, H. M., & Rainbolt, H. (2017). What triggers imposter phenomenon among academic faculty? A critical incident study exploring antecedents, coping, and development opportunities. Human Resource Development International, 20(3), 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E. R. (2018). Leadership impostor phenomenon: A theoretical causal model. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 11(1), 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M. S., Lee, S. E., Song, S. M., & Kim, S. J. (2019). A qualitative study on the experiences of home day care center directors. Journal of Human Development Research, 26(3), 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. Y., Koo, J. Y., Kim, H. J., & Cha, K. J. (2020). [2019 revised Nuri Curriculum] study on monitoring and support measures (I) (Research Report No. RRI 2020-24). Korea Institute of Child Care and Education. Available online: https://repo.kicce.re.kr/bitstream/2019.oak/5093/2/GR2008.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Kim, G. Y., & Lee, Y. H. (2023). The effects of athletes’ imposter syndrome tendency on achievement goal orientation and regulatory focus. Journal of Physical Education and Sports Science, 34(3), 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U. (2006). Confucianism, democracy, and the individual in Korean modernization. In Transformations in twentieth century Korea (pp. 221–244). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- LaDonna, K. A., Ginsburg, S., & Watling, C. (2018). “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: What physicians’ self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Academic Medicine, 93(5), 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. J., & Park, S. K. (2018). A consensual qualitative research on the difficulties experienced by national childcare center beginning directors. Open Early Childhood Education Research, 23(1), 451–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. W., Kim, N. Y., Kim, M. G., Kim, M. G., Kim, Y. O., Kim, E. S., Son, I. S., Yang, O. S., Chung, J. H., Chun, H. S., Choi, Y., & Kim, M. J. (2018). Paradigm shift in childcare policy and policy tasks for an ultra-low birth rate society and an inclusive welfare state (Project Report No. 2019-02). Korea Institute of Child Care and Education. Available online: https://repo.kicce.re.kr/handle/2019.oak/1771 (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Leonhardt, M., Bechtoldt, M. N., & Rohrmann, S. (2017). All impostors aren’t alike–differentiating the impostor phenomenon. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B. Y. (2017). A study for revision of “play” based national early childhood curriculum for future society. Educational Innovation Research, 27(4), 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Han, Y., Lu, Z. A., Cao, C., & Wang, W. (2023). The relationship between perfectionism and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students: The mediating roles of self-compassion and impostor syndrome. Current Psychology, 42(22), 18823–18831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S. (2021). “They overestimate me all the time:” Exploring imposter phenomenon among Indian female software engineers. Metamorphosis, 20(2), 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, L. N., Gee, D. E., & Posey, K. E. (2008). I feel like a fraud and it depresses me: The relation between the impostor phenomenon and depression. Social Behavior and Personality, 36(1), 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education & Ministry of Health and Welfare. (2019). 2019 revised Nuri curriculum. Ministry of Education.

- Morse, J. M. (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C. S. (2012). Study on the formation of leadership of a principal in a childcare center. Journal of Early Childhood Education, 16(6), 435–461. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. B. (2019). Type of daycare center parents’ complaints and seeking for principals’ countermeasures. Korean Journal of Early Child Care and Education, 117, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, S., Bechtoldt, M. N., & Leonhardt, M. (2016). Validation of the impostor phenomenon among managers. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. (2023). Seoul childcare portal’s childcare staff status of childcare centers [Data set]. Seoul Metropolitan Government. Available online: https://iseoul.seoul.go.kr/portal/mainCall.do (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Shin, K. Y., & Jeong, C. H. (2002). Tradition and democracy in South Korea. Korean Sociology, 36(3), 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tewfik, B. A., Yip, J. A., & Martin, S. R. (2025). Workplace impostor thoughts, impostor feelings, and impostorism: An integrative, multidisciplinary review of research on the impostor phenomenon. Academy of Management Annals, 19(1), 38–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergauwe, J., Wille, B., Feys, M., De Fruyt, F., & Anseel, F. (2015). Fear of being exposed: The trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. (2020). The links between imposter phenomenon and implicit theory of intelligence among Chinese adolescents. In 2020 5th International Conference on Modern Management and Education Technology (MMET 2020) (pp. 1–10). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D. (2022). For you who can’t get started today either. Hanbit Biz. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H. J., & Heo, Y. R. (2012). Study on some characteristics of day-care center directors centered on servant-leadership. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education, 72, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, M. K., & Bae, J. H. (2021). Efforts, difficulties, and demands of home-based childcare center directors for implementing parent education. Open Early Childhood Education Research, 26(4), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. W. (2016). The historical emergence and reproduction of growthism as dominant discourse in Korea. Korean Society, 17(1), 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).