Slow Pyrolysis of Quercus cerris Cork: Characterization of Biochars and Pyrolysis Volatiles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

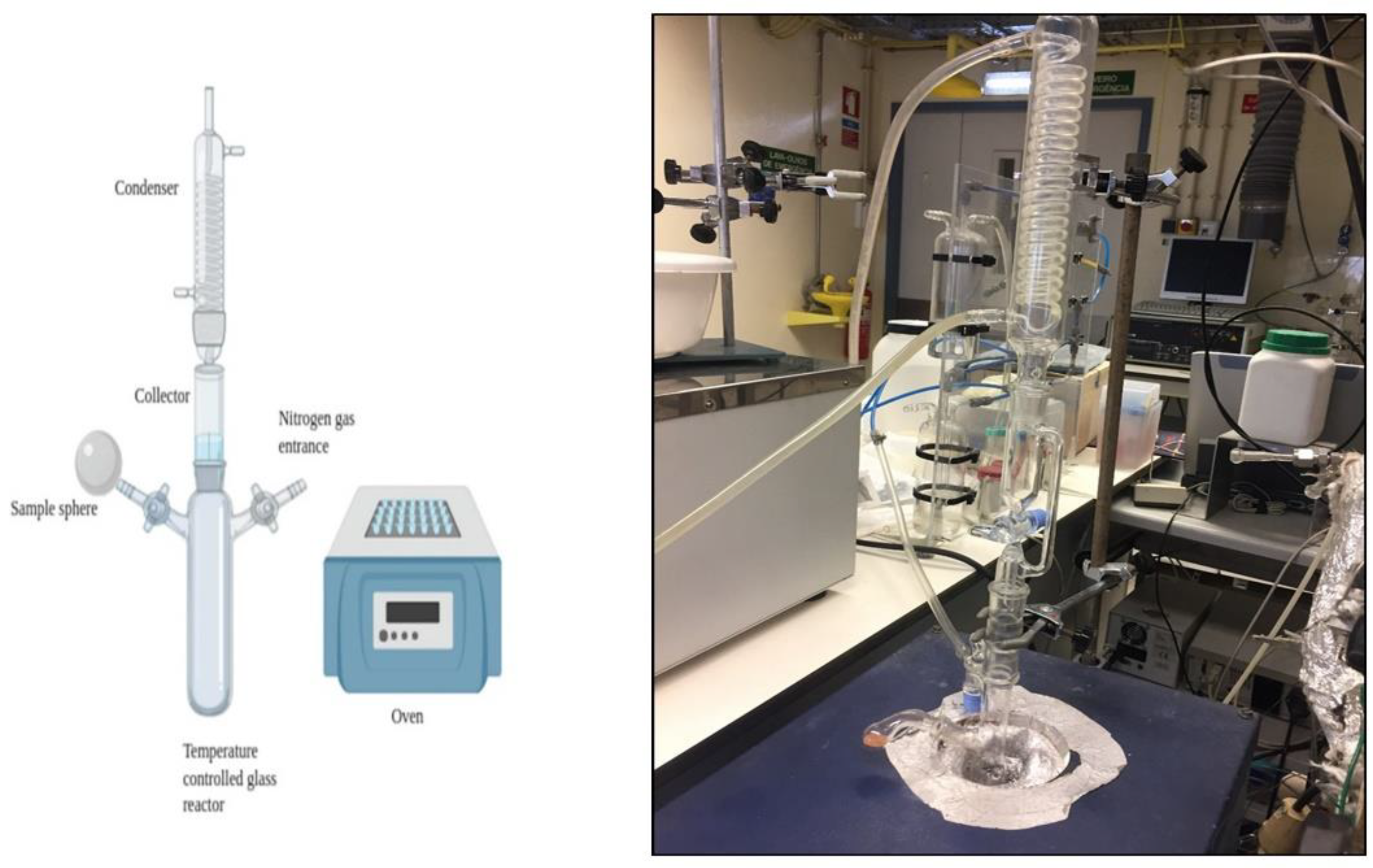

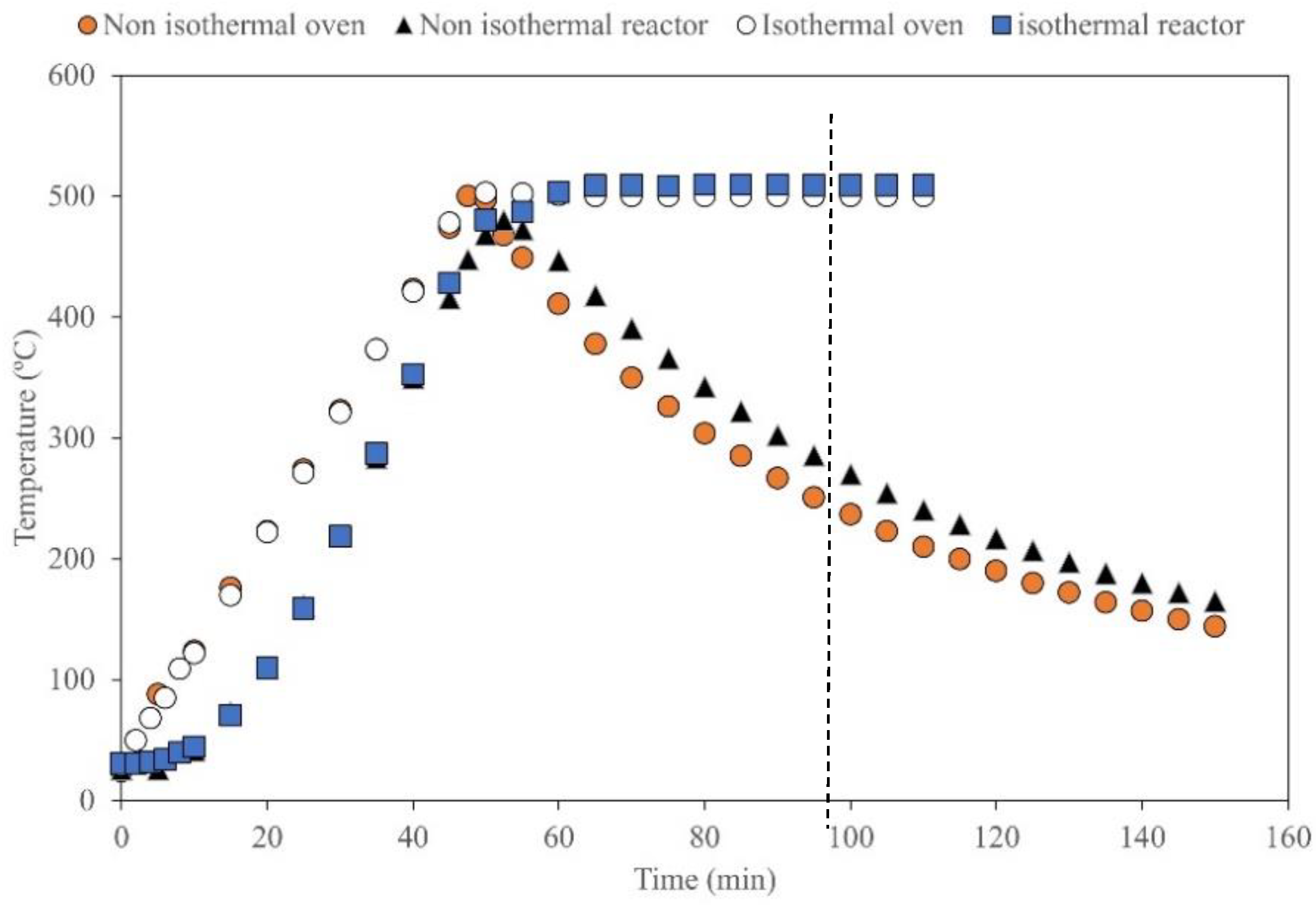

2.2.1. Isothermal and Non-Isothermal Slow Pyrolysis

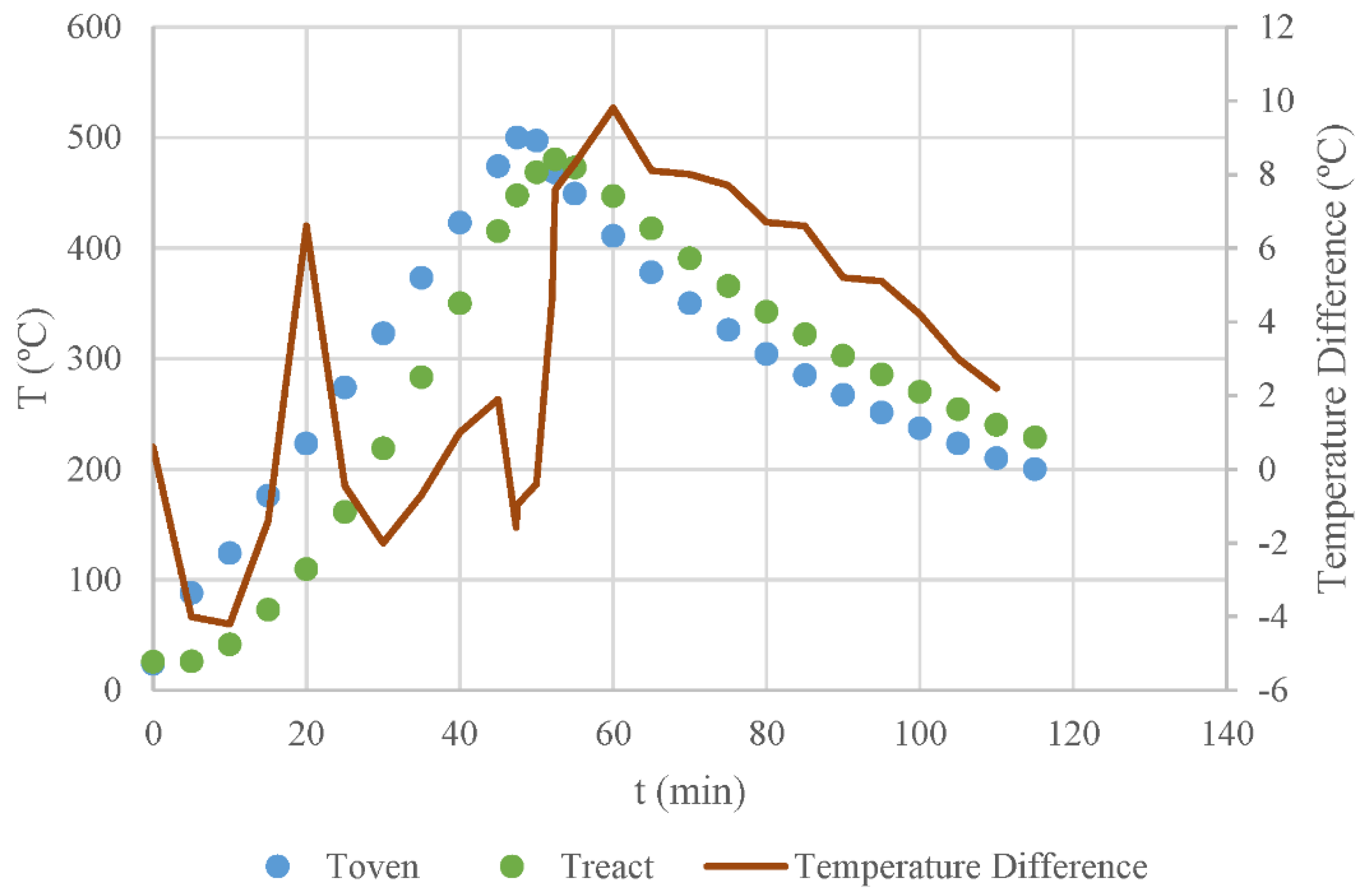

2.2.2. Differential Thermal Analysis of Reactor Operation

2.2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.2.4. FT-IR Analysis

2.2.5. Determination of Fuel Properties of Biochars

2.2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.2.7. Hydrocarbon Composition of Pyrolysis Volatiles

3. Results

3.1. The Mass Balance

3.2. Differential Thermal Analysis of Reactor Data

3.3. The Effect of Temperature on the Surface Chemical Groups of Cork Biochars

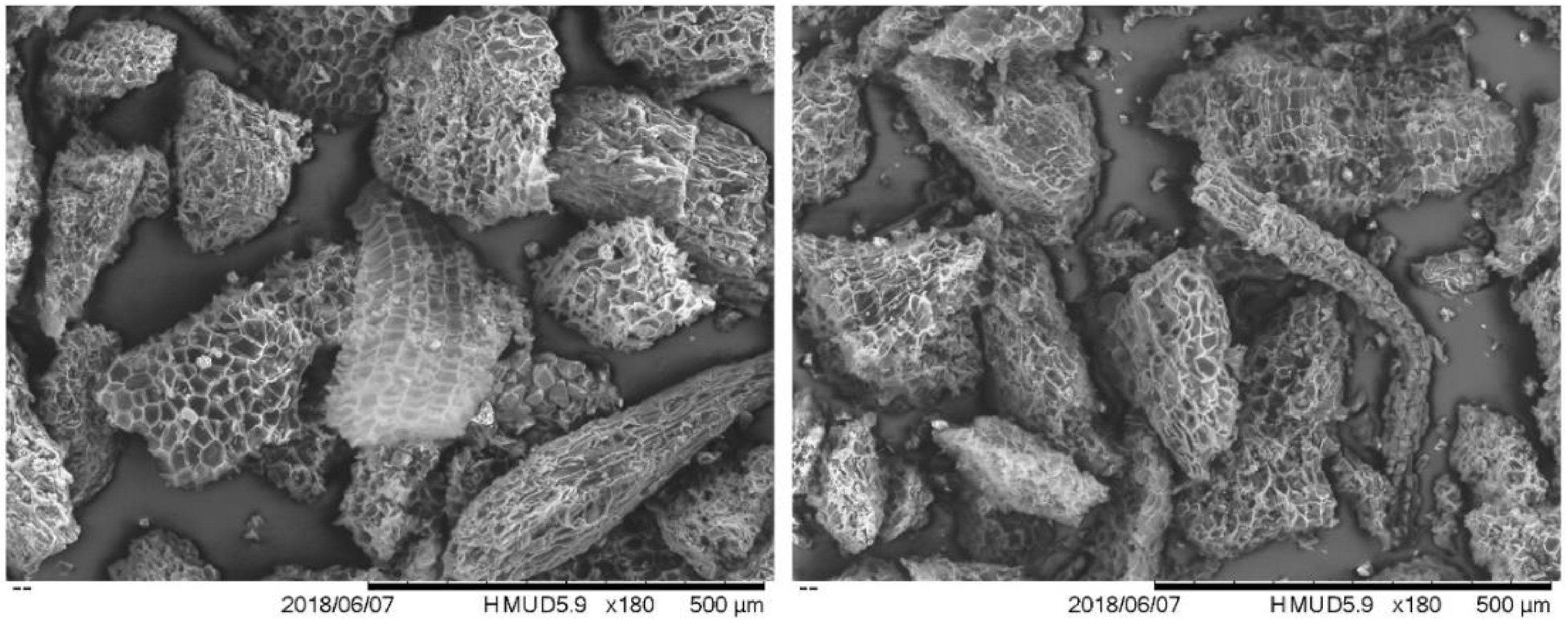

3.4. The Morphology of Cork Biochars

3.5. Fuel Properties and Application of Cork Biochars

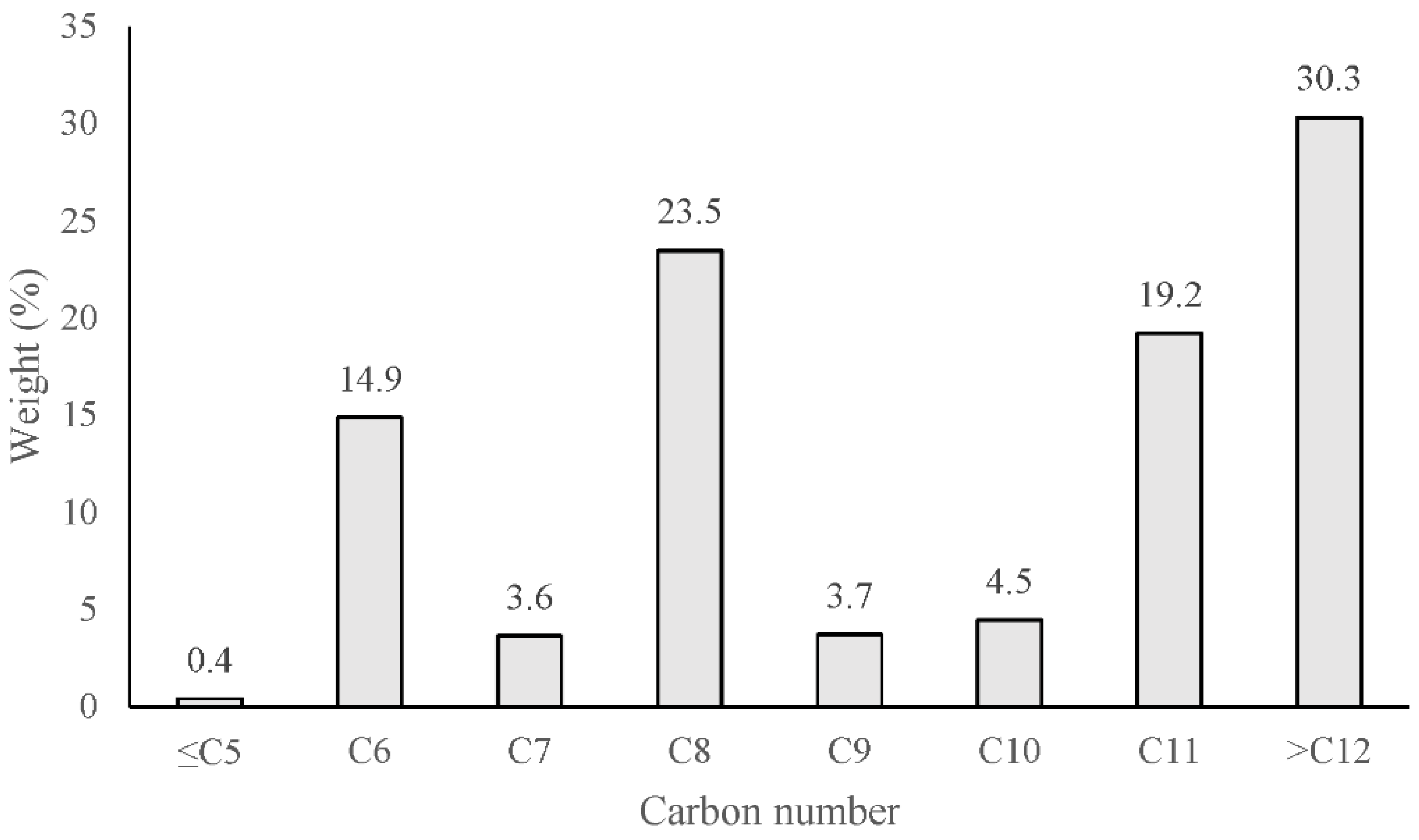

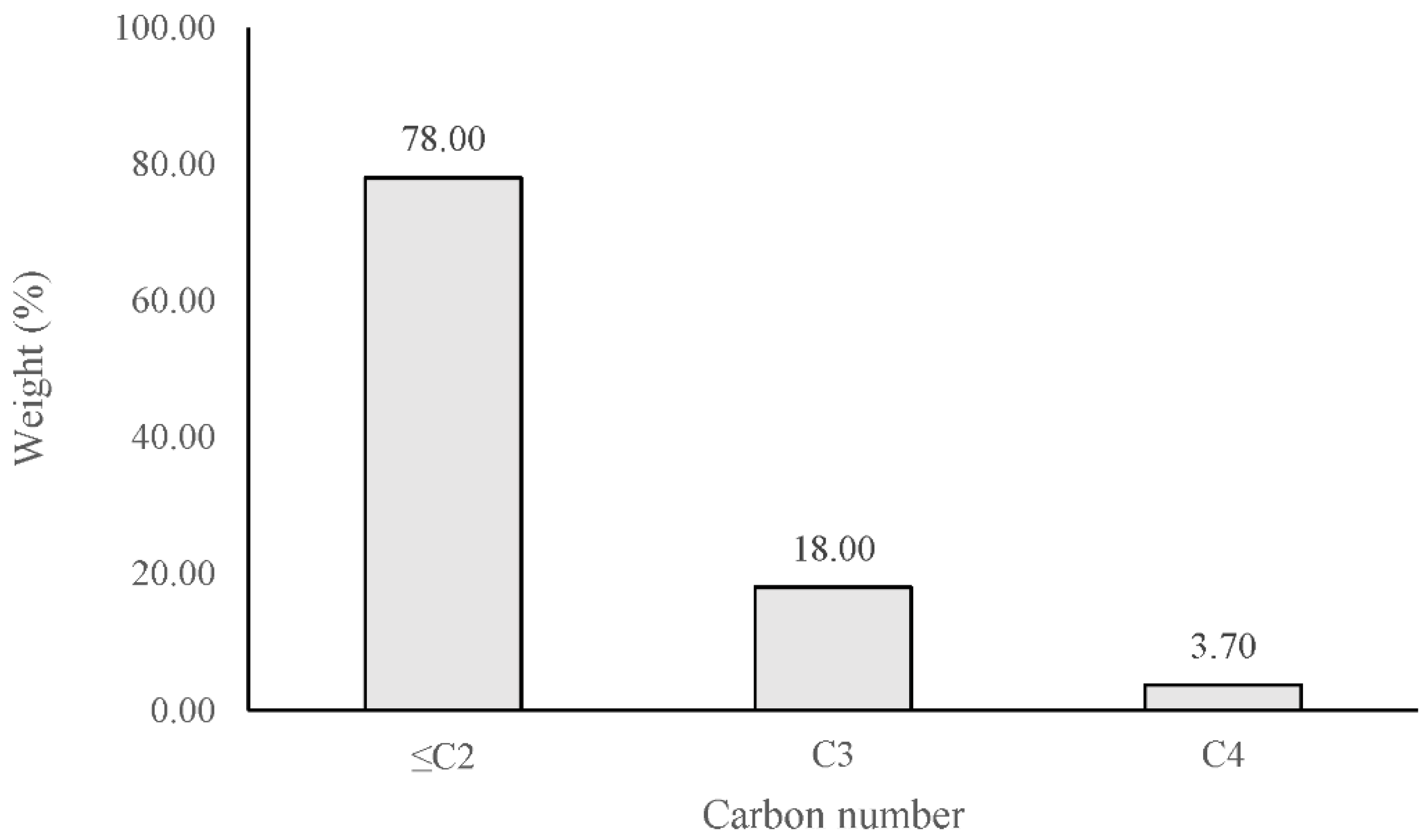

3.6. Hydrocarbon Composition of Cork Bio-Oil and Pyrolysis Gas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The slow pyrolysis of Quercus cerris cork results in approximately 32% biochars, 18% condensates, and 50% pyrolysis gas.

- Cork undergoes a slightly exothermic process during slow pyrolysis, possibly associated with decarboxylation reactions, which reduces the required amount of external heat.

- Cork suberin undergoes degradation during slow pyrolysis.

- Decarboxylation and aromatization occur in cork pyrolysis, most noticeably under isothermal conditions.

- The hydrocarbon fraction of cork bio-oil consists of C5–C12 compounds with C8 compounds making the main fraction. The hydrocarbon fraction of the cork pyrolysis gas is composed mainly of C1–C2 compounds.

- The non-isothermal pyrolysis is a promising method for producing biochars at a lower cost than isothermal pyrolysis.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamm, B.; Kamm, M.; Gruber, P.R.; Kromus, S. Biorefinery systems–An overview. Biorefineries-Industrial Process. In Biorefineries-Industrial Processes and Products: Status Quo and Future Directions; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini, F. The biorefinery concept: Using biomass instead of oil for producing energy and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, A.; Ozturk, T.; Demirbas, M.F. Recovery of Energy and Chemicals from Carbonaceous Materials. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2006, 28, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, R.L.; Broer, K. Gasification; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dahmen, N.; Henrich, E.; Dinjus, E.; Weirich, F. The bioliq® bioslurry gasification process for the production of biosynfuels, organic chemicals, and energy. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2012, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, T. Challenges and Opportunities in Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass: Part I. Johns. Matthey Technol. Rev. 2018, 62, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A.V.; Peacocke, G.V.C. Fast pyrolysis processes for biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2000, 4, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.R.; Wright, M.M.; Brown, R.C. Estimating profitability of two biochar production scenarios: Slow pyrolysis vs fast pyrolysis. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2011, 5, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasztory, Z.; Mohácsiné, I.R.; Gorbacheva, G.; Börcsök, Z. The utilization of tree bark. BioResources 2016, 11, 7859–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.Q.; Rai, C. A kinetic model for pyrolysis of Douglas fir bark. Fuel 1978, 57, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengel, D.; Wegener, G. Wood: Chemistry, ultrastructure. Reactions 1984, 613, 1960–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström, E. Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications; Gulf Professional Publishing: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993; ISBN 0-12-647481-8. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, C.; Pereira, H. Cork-containing barks—A review. Front. Mater. 2017, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Şen, A.; Miranda, I.; Santos, S.; Graça, J.; Pereira, H. The chemical composition of cork and phloem in the rhytidome of Quercus cerris bark. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2010, 31, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.; Leite, C.; Lima, L.; Lopes, P.; Pereira, H. Industrial valorization of Quercus cerris bark: Pilot scale fractionation. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 92, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.; Miranda, I.; Ferreira, J.; Lourenço, A.; Pereira, H. Chemical composition and cellular structure of ponytail palm (Beaucarnea recurvata) cork. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 124, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, M.; Olofsson, I.; Pommer, L.; Wiklund-Lindström, S.; Åberg, K.; Nordin, A. Effects of temperature and residence time on continuous torrefaction of spruce wood. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 134, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, A.; Hedden, K. A non-isothermal experimental technique to study coal extraction with solvents in liquid and supercritical state. Fuel 1986, 65, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, C.; Branca, C.; Galgano, A. On the Experimental Evidence of Exothermicity in Wood and Biomass Pyrolysis. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwat, W.; Hasegawa, I.; Tani, T.; Sunagawa, K.; Mae, K. Analysis of Cross-Linking Behavior during Pyrolysis of Cellulose for Elucidating Reaction Pathway. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 5765–5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.; Marques, A.V.; Gominho, J.; Pereira, H. Study of thermochemical treatments of cork in the 150–400°C range using colour analysis and FTIR spectroscopy. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2012, 38, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, C.; Şen, A.; Durão, L.; Miranda, I.; Pereira, H.; Gonçalves, M. Low-temperature pyrolysis products of waste cork and lignocellulosic biomass: Product characterization. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, A.; Nobre, C.; Sen, A.; Panizio, R.; Brito, P.; Gonçalves, M. Torrefaction Upgrading of Heterogenous Wastes Containing Cork and Chlorinated Polymers. Environments 2022, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.U.; Fonseca, F.G.; Funke, A.; Pereira, H.; Lemos, F. Pyrolysis kinetics and estimation of chemical composition of Quercus cerris cork. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 12, 4835–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R.L.; Yang, J.; Ding, Z. Raman and FTIR spectroscopy of natural oxalates: Implications for the evidence of life on Mars. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2003, 48, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, W.T.; Rochliadi, A.; Arcana, I.M. Nanocellulose prepared by acid hydrolysis of isolated cellulose from sugarcane bagasse. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Solo, Indonesia, 2015; Volume 107, p. 12045. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, S.; Kadla, J.F. Hydrogen Bonding in Lignin: A Fourier Transform Infrared Model Compound Study. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 2815–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Agarwal, U.P.; Hirth, K.C.; Matuana, L.M.; Sabo, R.C.; Stark, N.M. Chemical modification of nanocellulose with canola oil fatty acid methyl ester. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 169, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aller, D.; Bakshi, S.; Laird, D.A. Modified method for proximate analysis of biochars. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2017, 124, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ronsse, F.; van Hecke, S.; Dickinson, D.; Prins, W. Production and characterization of slow pyrolysis biochar: Influence of feedstock type and pyrolysis conditions. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis: Practical Design and Theory; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 0080961622. [Google Scholar]

- Galadima, A.; Muraza, O. In situ fast pyrolysis of biomass with zeolite catalysts for bioaromatics/gasoline production: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 105, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, A. V Review of fast pyrolysis of biomass and product upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.V.; Pereira, H. Aliphatic bio-oils from corks: A Py–GC/MS study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 109, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Huang, M.-Y.; Chang, J.-S.; Chen, C.-Y. Thermal decomposition dynamics and severity of microalgae residues in torrefaction. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 169, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Cheng, C.-L.; Show, P.-L.; Ong, H.C. Torrefaction performance prediction approached by torrefaction severity factor. Fuel 2019, 251, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lai, Z.; Mu, J.; Chu, D.; Zang, X. Converting industrial waste cork to biochar as Cu (II) adsorbent via slow pyrolysis. Waste Manag. 2020, 105, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, H. The thermochemical degradation of cork. Wood Sci. Technol. 1992, 26, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.V.; Pereira, H.; Meier, D.; Faix, O. Quantitative analysis of cork (Quercus suber L.) and milled cork lignin by FTIR spectroscopy, analytical pyrolysis, and total hydrolysis. Holzforschung-Int. J. Biol. Chem. Phys. Technol. Wood 1994, 48, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, E.M.; Correlo, V.M.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Cork–polymer biocomposites: Mechanical, structural and thermal properties. Mater. Des. 2015, 82, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duman, G.; Okutucu, C.; Ucar, S.; Stahl, R.; Yanik, J. The slow and fast pyrolysis of cherry seed. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pituello, C.; Francioso, O.; Simonetti, G.; Pisi, A.; Torreggiani, A.; Berti, A.; Morari, F. Characterization of chemical–physical, structural and morphological properties of biochars from biowastes produced at different temperatures. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, H.; Yin, J.; Yang, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Cao, X. Pyrolysis temperature-dependent carbon retention and stability of biochar with participation of calcium: Implications to carbon sequestration. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.U.; Nobre, C.; Durão, L.; Miranda, I.; Pereira, H.; Gonçalves, M. Low-temperature biochars from cork-rich and phloem-rich wastes: Fuel, leaching, and methylene blue adsorption properties. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 12, 3899–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, A.U.; Pereira, H. State-of-the-Art Char Production with a Focus on Bark Feedstocks: Processes, Design, and Applications. Processes 2021, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H. Chapter 13—Cork agglomerates and composites. In Cork; Pereira, H., Ed.; Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 289–303. ISBN 978-0-444-52967-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, L. Effects of feedstock type, production method, and pyrolysis temperature on biochar and hydrochar properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 240, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, X.; Gu, Z.; Polin, J. Carbon materials from high ash biochar for supercapacitor and improvement of capacitance with HNO3 surface oxidation. J. Power Sources 2013, 236, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, A.; Hanley, K.; Whitman, T.; Joseph, S.; Lehmann, J. Characterization of biochars to evaluate recalcitrance and agronomic performance. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 114, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 1134489536. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Camps-Arbestain, M.; Hedley, M.; Bishop, P. Predicting phosphorus bioavailability from high-ash biochars. Plant Soil 2012, 357, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, H.S.; Park, H.J.; Park, Y.-K.; Ryu, C.; Suh, D.J.; Suh, Y.-W.; Yim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-S. Bio-oil production from fast pyrolysis of waste furniture sawdust in a fluidized bed. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, S91–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabangu, S.; Woolf, D.; Fisher, E.M.; Angenent, L.T.; Lehmann, J. Techno-economic assessment of biomass slow pyrolysis into different biochar and methanol concepts. Fuel 2014, 117, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, R.M.; Platon, A.; Satrio, J.A.; Brown, R.C. Techno-economic analysis of biomass-to-liquids production based on gasification. Fuel 2010, 89, S11–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Uddin, N.; Daud, W.W.; Abbas, H.F. Potential hydrogen and non-condensable gases production from biomass pyrolysis: Insights into the process variables. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, E.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y. Dry and steam reforming of biomass pyrolysis gas for rich hydrogen gas. Biomass-Bioenergy 2015, 78, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Products (%) | Isothermal Pyrolysis | Non-Isothermal Pyrolysis |

|---|---|---|

| Biochar | 32.3 ± 3.9 | 32.2 ± 15.8 |

| Condensate | 18.0 ± 6.3 | 16.7 ± 1.1 |

| Gas | 49.8 ± 2.4 | 51.2 ± 14.6 |

| Raw Cork | I-Char | G-Char | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 53.8 | 63.5 | 71.5 |

| H | 6.5 | 5.3 | 3.6 |

| O | 39.7 | 31.2 | 24.9 |

| O/C H/C | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.26 |

| 1.44 | 0.99 | 0.60 | |

| HHV | 19.7 | 21.3 | 22.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sen, U.; Martins, M.; Santos, E.; Lemos, M.A.; Lemos, F.; Pereira, H. Slow Pyrolysis of Quercus cerris Cork: Characterization of Biochars and Pyrolysis Volatiles. Environments 2023, 10, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10010004

Sen U, Martins M, Santos E, Lemos MA, Lemos F, Pereira H. Slow Pyrolysis of Quercus cerris Cork: Characterization of Biochars and Pyrolysis Volatiles. Environments. 2023; 10(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleSen, Umut, Marta Martins, Everton Santos, Maria Amelia Lemos, Francisco Lemos, and Helena Pereira. 2023. "Slow Pyrolysis of Quercus cerris Cork: Characterization of Biochars and Pyrolysis Volatiles" Environments 10, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10010004

APA StyleSen, U., Martins, M., Santos, E., Lemos, M. A., Lemos, F., & Pereira, H. (2023). Slow Pyrolysis of Quercus cerris Cork: Characterization of Biochars and Pyrolysis Volatiles. Environments, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments10010004