4.2. LULC Change Trajectories in the KV

Until the 1980s, the urban areas (interchangeably used as built-up areas) of KV were limited within the confines of the historic settlements of the five municipalities. The outward expansion of the urban area began in the early 1990s and accelerated at the turn of the 20th century. In the 2000s, the built-up areas continued to expand further along the major roads that link the outskirts of the five municipalities and there is no sign that it is going to stop anytime in the near future, as more complex road networks are being planned for the future. Most of the newly expended built-up areas are replacing agricultural lands that once were considered to be the most fertile and productive in the country.

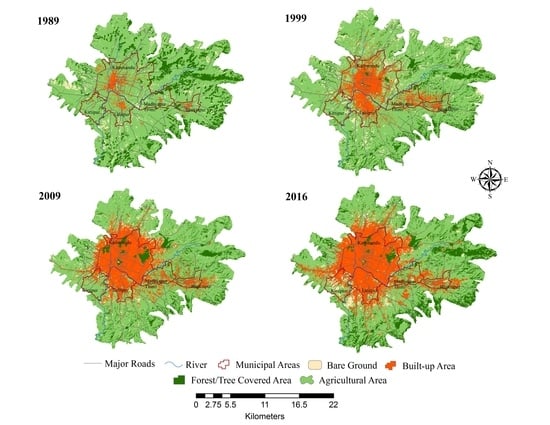

Table 4 summarizes the LULC change trends from 1989 through 2016 obtained from the classified images. From 1989 to 2016, built-up area increases from 2153 to 11,019 hectares (ha)—an increase of 412% is a very significant change, because much of the new developments occurred as an expansion of the existing city cores (

Figure 2). At present, built-up area comprises about 26% of the study site, whereas agricultural area diminished at a rate of 1.8% per year resulting in a total 32% loss during the period of 1989–2016. Currently, the extent of the agricultural area is around 55% of the central KV compared to 82% in 1989 (

Table 4). The rate of conversions of agricultural land to other types of land uses remains high throughout the study period (see details in

Section 4.3). The loss of agricultural land in the KV resembles the worldwide trend of the urban conversions of agricultural lands reported elsewhere [

45,

46,

47], but much is unknown about how these conversions will affect fragile ecosystems of this mountainous valley, including with the loss of green space, sealing of soil, disturbance to stream corridors, and alteration of agro-ecological services (e.g., water retention, vegetation, air circulation).

The forested or tree covered area comprises a small portion of the central KV, which include urban parks (e.g., Bhandarkhal, Boudha), forest resorts (e.g., Mrigasthali), forest reserves (e.g., Gokarna), and some forest patches on the steep slopes. Forest patches in the central KV are well maintained and only observed a marginal loss in last four decades. Covering around 4% area of the central KV, bare grounds are scattered largely at the outskirts of the Kathmandu city. The use of these privately-owned lands depends on the location of these lands. The bare grounds proximate to hilly areas are used for agriculture, whereas, the bare grounds located at the outskirts of the city are mostly cleared up to expand the built-up area.

4.3. LULC Change Pattern

To further explore the LULC change pattern, we created confusion matrices for 1989–2016, 1989–1999, 1999–2009, and 2009–2016 changes (see

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8). In all of the tables, unchanged pixels are located along the major diagonal of the matrix. Conversion values were sorted by area and listed in descending order [

48].

The results of

Table 5 indicate that the increase in the built-up area mainly came from the conversion of agricultural land to urban area in this 27-year study period, 1989–2016.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the transition among land use classes in the period of 1989–2016. The built-up area expanded radially towards all direction at the rate of 14.70% per annum. The conversion to built-up area mostly happened within 500 m of major roads in KV (see

Figure 2). The conversion of active agricultural land to bare ground or perennial fallows at the urban fringes shows a booming housing market during this period. This type of conversion is the initial step of urban expansion, which subsequently opens up the areas for housing developments. Of the 34,000 ha of agricultural land in 1989, around 26% (8880 ha) has been converted into built-up area within 2016. This result supports the fact that there was a huge surge in the rural-to-urban migration in the KV between the mid-1990s to the late 2000s—the proximate causes are discussed in

Section 4.4.

Table 5 and

Figure 2 also show some conversions of agricultural lands to forest areas occurring at the outer margins of our study area that are adjacent to the densely forested areas. Although more precise ground validation is needed, this trend indicates the discontinuation of agricultural activities on marginal, steep-sloped lands could pave the way for shrublands and secondary forests (see

Figure 2). Similarly, approximately 18% (742 ha) tree covered area has been converted into agricultural lands, and most of these changes occurred in the peri-urban areas with lower elevation and slopes. It is not clear exactly what contributed to this change. It is important to note that this conversion took place in the areas far from the city area. It is also important to note that there has been a minimal change in tree-covered areas within the city limit (see

Figure 3, for instance). The shifting from fallow to agricultural is seasonal, largely driven by monsoon rainfall patterns, local economy, and the availability of agricultural labor. The water area occupies very little space of the valley and has not been changed much in last three decades.

During the ten years between 1989 and 1999, the built-up area increased by about 120%, whereby significant expansion took place along the major roads such as local roads, service roads, and access roads that link the outlying towns with the five municipalities (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The Kathmandu and Lalitpur municipalities experienced substantial growth in the built-up areas. The built-up areas were further expanded into the Madhyapur Thimi and Bhaktapur municipalities, and also in the southern parts of Duwakot and Jhaukhel VDCs. This growth of built-up area was primarily obtained by converting agricultural lands. Around 10% of the agricultural lands were converted into built-up areas in this period (see

Table 6). Our analysis also reveals that as distance increases away from these major roads, the built-up areas tend to be less dense with the presence of open space and agriculture land. In other words, households select the locations that reduce their travel time and hence the concentration of settlement along the 500 m of major road networks.

The most aggressive form of urban growth in the KV happened between the period 1999 and 2009, which also coincides with the booming period of the real estate market largely fueled by the influx of migrants from the countryside displaced by political turmoil and/or by stagnant growth in agricultural sector. During this period (1999–2009), the KV saw 117% growth in built-up areas. This expansion came at the expense of 18% agricultural lands (see

Table 7). The majority of this expansion occurred in Kathmandu and Lalitpur municipal areas, and for the first time in history, entire areas of these municipalities became urbanized (see

Figure 3). The built-up area further stretched to eastward VDCs (i.e., Tathali, Sudal) expanding further beyond the Bhaktapur municipal boundary. In this decade, new built-up areas were established in the southeastern VDCs (e.g., Balkot, Tikathali, Sirutar, Lubhu), and along the major roads connecting the valley to the rest of the country. During this period, the valley also observed a substantial loss of forest cover whereby about 36% of the tree-covered area were cleared up for agriculture purpose. The rapid growth of built-up areas pushed the farmers to clear up the forest and expand agriculture on the foothills (see

Figure 3). Overall, this fast growth of built-up areas during 1989–2009 can be attributed to the spike in real estate market, massive urban in-migration compounded by political instability in the countryside.

For the period between 2009 and 2016, two major LULC changes are worth noting: (1) forest area has been in a relatively stable condition in the central KV and is slowly beginning to expand in the outer margins, and (2) the aggressive urban growth of the 1999–2009 period has somewhat slowed down in the last ten years. The further expansion of forest areas in the KV outskirts, particularly in the northwestern part is notable; however, it is unclear which proximate causes are driving this change. One potential cause is that this area covers the Shivpuri Nagarjun National Park, which was formerly a watershed and wildlife reserve, but it was upgraded to a national park status in 2002 to more aggressively protect the forest areas and watershed vital to the water supply of the KV. Although the ground verification is needed, the areas in higher elevation and slopes that are adjacent to these forest areas are likely to have gained forest coverage. There are also some community forests located near those forest patches, where communities are taking more active roles in managing forest resources. One could argue that except for the protected forests, most forest patches are heavily fragmented, which is often consistent with reported cases of land fragmentation in the peri-urban area or urban fringes (see [

49,

50]).

Our analysis also reveals that urban growth has seen a slight slowdown in certain parts of the valley in recent years. Between 2009 and 2016, the built-up area increased only about 8% (see

Table 8). The most noticeable growth was in Kirtipur municipality and the built-up areas in the KV were mostly expanding only along the major roads, radially growing outward from Kathmandu metropolitan area. Thapa & Murayama [

13] predicted such outward urban growth and in-filling of existing urban areas. The built-up areas of some of the fastest growing areas, such as Madhyapur Thimi and Bhaktapur municipal areas ceased to expand in this period (see

Figure 3). Overall, our results show that the KV cityscape has changed dramatically between 1989 and 2016. Because of the aggressive urban growth experienced since the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, the KV is showing a concentric pattern of urbanization. It is worthwhile to note that there were five distinct municipalities with distinct urban boundaries and plenty of open or green space between them until the late 1980s; however, those municipalities have since coalesced into a large metropolitan area where agricultural lands and open spaces were aggressively converted to residential areas to accommodate growing demands for housing and other urban infrastructures.

4.4. Key Drivers of LULC Change in KV

The results of the LULC change detection clearly establish that this valley has experienced an unprecedented level of urban growth in the last three decades. The final quarter of the 20th century witnessed a rapid expansion of the KV, reflecting the trend of urban growth dominant in the Himalayan region and elsewhere in South Asia [

4]. This trend transformed the KV composed of the network of small towns—each with their own place-based identities and sophisticated architectural heritage—into a metropolis of ‘concrete jungle’, struggling to preserve its historical identity and ecosystem services [

5]. Based on a careful review of the existing literature and expert knowledge, two of the co-authors have several years of working experience in Nepal, we identified that several proximate causes that have directly contributed to this transformation, including (a) rural-urban migration, (b) economic centrality, (c) socio-political factors, and (d) booming real estate market. All of these are arguably related to government policies (or the lack thereof).

4.4.1. Rural-Urban Migration

The KV has been experiencing rapid population growth particularly since the 1980s. Being the home of 22.3% Nepal’s urban population, KV is the fastest growing urban agglomeration in South Asia [

8]. The highest contribution of this growth comes from rural to urban migration, which in turn is driven by the economic opportunities available in the capital relative to the rural areas. For instance, during the 1990s as high as 40% population growth happened due to urban in-migration [

51]. Currently, the net inflow of migrants accounts for 36% of KV populations [

52]. Hailed from the remote rural areas they mostly migrate because of economic reasons (i.e., better livelihood opportunities) and educational purpose. However, rural push factors play a dominant role in urban in-migration too [

10]. Extreme poverty, lack of economic opportunities, low living standard, and an absence of basic amenities in the rural areas are some of the many push factors. Moreover, the civil conflict escalated the migration in recent decades [

53]. While farmlands in conflict-affected areas were facing labor shortage, the displaced people also became the driver of LULC change in the KV.

4.4.2. Economic Centrality

The KV is also the administrative and economic hub of the country with a growing middle class [

54]. The relatively flat topography, transportation accessibility, economic opportunities, and political and policy factors have consolidated the centrality feature of KV [

1,

10,

11,

14]. Among all of these factors, economic centrality is considered as the prime factor of rapid land use change. With the concentration of social services—primarily the growth of higher education and healthcare industry--and growing economic opportunities in tourism and other service sectors, the capital city has remained the most preferred destination for seeking jobs, income generation opportunities, and residence. This was further compounded by limited investment opportunities elsewhere in the country and/or other economic sectors in the cities. Similarly, the entire largest manufacturing cluster is concentrated in the KV, which provides as much as 40% manufacturing employment and 41% nonfarm and service employment [

52]. Manufacturing employment per square kilometer is above 600 in the Kathmandu city area [

55], the highest in the country, which in turn has attracted people to change their occupations from farming to manufacturing. In addition, centralization of government offices, the growth of foreign aid and tourism, and construction of access roads connecting the KV with the rest of Nepal have further propagated the economic centrality. This capital-centric development model (or urban primacy) that is typical of several low to middle-income countries has been one of the main drivers of LULC change in KV. The KV is Nepal’s gateway to tourists, whereby 90 percent of tourists enter the country [

56], as the valley also has the rich cultural heritage including the seven designated world heritage sites. Tourism is also a key component of the valley’s economy [

57], putting pressure on agriculture land to build facilities for continued flow of tourists and a growing middle class further away from the city core.

4.4.3. Socio-Political Factors

There has also been a huge influx of internally displaced people to the valley due to the decade-long civil unrest that began in the mid-1990s [

58]. While triggering the socio-political crisis, the conflict disrupted local economic activities by frequent strikes, closures of businesses, extortion, and threats. More than 500,000 people believed to have been displaced during the insurgency period [

56]. Nepal’s urban centers, especially KV, had to absorb the influx of these migrants. As a capital city, Kathmandu is naturally the political and administrative center of the country, and it also became a safe refuge for those internally displaced people during the political turmoil period of 1996 to 2008. Overall, the KV is the hub for all important socio-economic sectors in the country: tourism, finance, industry, education, transportation, and healthcare.

4.4.4. Real Estate Boom

Nepal in general and KV more specifically, experienced a real estate boom in the recent decades, especially between the mid-1990s to the late 2000s. According to Nepal Land and Housing Association, the land price in the KV risen by 300% since 2003, one of the key drivers of LULC change. Land ownership in the KV can be divided into private,

Guthi (religious trust), government, and public. With more than 90 percent of cultivated lands and 61 percent of registered lands, private land ownership is a dominant form of tenure arrangement in the valley [

59]. This means that there is little government control over land and housing in the KV, and the absence of real land-acquisition laws in practice, the state has not effectively regulated in the booming real estate market. During the fiscal year of 2008–2009 close to 185,000 people and firms bought new land and housing in the valley [

60]. While there is no accurate data of how real estate agencies are currently involved in the land market, our interactions with local government officials reveal that there are as much as 150 real estate agencies and about a dozen of housing companies involved in land acquisitions, pooling, and housing in the KV. The increasing number of middle-class families in the KV is demanding new modern facilities such as, housing sub-divisions and colonies with modern amenities (e.g., private parking, modern grocery stores, restaurants) in the suburbs further contributing the LULC change in the fringe areas of the valley.

These key proximate causes of LULCC detected in KV are obviously interlinked and quite complex, but it is safe to argue that the economic centrality and urban population growth swelled primarily by the rural-to-urban migration played the major role in the rapid urban growth of the KV. It is essentially the large differences in economic opportunities between the KV and the rest of the country that resulted in a growing influx of people from rural areas to the KV.