1. Introduction

Local self-government refers to specific institutions or entities created by national constitutions (Brazil, Denmark, France, India, Italy, Japan, Sweden), state constitutions (Australia, USA), ordinary legislation of the higher level of central government (New Zealand, United Kingdom, most countries), provincial or state legislation (Canada, Pakistan) or under executive power (China) to provide a range of specific services in a relatively small geographically defined area. Local governance is a broader concept and is defined as the formulation and implementation of collective action at the local level. It therefore includes the direct and indirect roles of formal local self-government institutions and government hierarchies, as well as the roles of informal norms, networks, community organizations, and associations of neighboring countries in carrying out collective action by defining a inhabitant–inhabitant framework and inhabitant–state interactions, collective decision-making, and provision of local public services (

Boadway and Shah 2009).

European Union (EU) countries are far from having a same territorial organizational structure, so the decision on a system of local action, including levels of governance, is left to the national level. Of the EU-28, nine countries use only one level of sub-state authorities (self-government); the other twelve countries have two regional levels (municipalities and regions); while the remaining seven have three levels below the national level (municipalities, regions, and intermediaries subjects) (

Halásková and Halásková 2015).

Fandel et al. (

2019) states that, for example, in the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic, competencies were gradually transferred from the state to territorial self-government, as territorial self-government was established as a new part of public administration during the decentralization process. In order to build a democratic society, it was necessary to strengthen local self-government with new competencies, which were initially performed only by state institutions, such as roads, registries, building regulations, social care, environment, sports, theatre, education, tourism, health, regional development, etc. The constitutions of some countries sometimes do not regulate the organization of local self-governments at all (for example, in the USA), but there are also countries where these relations are strictly regulated, for example in Brazil. The main source of the legal regulation of power relations in these subjects are the statutes of self-government. In some Länder (state level), there are cases where federal entities perform local self-government functions in addition to their own functions. This applies, for example, to the cantons of Switzerland, countries and cities in Germany and Austria (Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, and Vienna) (

Nam and Parsche 2001). There are two systems of local self-government organization: Anglo-American and European. The Anglo-American system is characterized by the presence of local self-government at all levels of the federation or state entity. At the same time, there are no administrative and territorial units of a general character. The European system is characterized by a combination of local self-government and state administration; in addition, it has other forms in which local self-governments are assigned certain functions by the state administration (

Lyubashits et al. 2019).

In most European countries, a participatory model of governance is applied in public administration, which the base is that state administration entities (central bodies, territorial bodies) and self-government entities (territorial and interest) participate on the administration of public affairs in mutual cooperation. The structure of local and regional self-government in European countries varies depending on their constitution, historical development, and size. For example, according to

Brezovnik et al. (

2019) in Slovenia, the National Government may delegate specific tasks to the local self-government, provided that the necessary funding is budgeted for their performance. The act on local self-government stipulates that the municipality independently administers local matters of a public nature (primary tasks) established by a general regulation of the municipality or a law. The central feature of the law is the model of calculating the eligible expenditures of the municipality and fiscal settlement. The model is based on a predetermined national average of funds per capita, with which the municipality can ensure the performance of all its tasks provided for in the constitution and law. Relevant per capita funding is determined annually as eligible per capita expenditure.

It follows that in order for local self-governments to be able to provide all the competencies, they need financial resources, which they can obtain from various sources. The most important economic instrument is the budget, while the management of local self-governments according to the set budget is mandatory by law in each country (

Peková 2011).

The aim of the paper is to characterize and to compare the mechanism of creating revenues of the local self-government in the Slovak and Czech Republic, and at the same time to analyze the relationships between individual groups of local revenues in the time period 2009–2018. As part of a comparative study we presented the theoretical aspects of the paper (part 2). Subsequently, we characterized the mechanism of creation of individual revenues of local governments (

Section 4.1), and using selected mathematical–statistical methods (

Section 3), we analyzed individual groups of local government revenues for the period 2009–2018 (

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3).

2. Theoretical Background

Economic theories, also legal sciences, distinguish four levels of government. However, we do not have to find these levels in all countries. It depends on the internal organization of the country, whether it is a federal state or a unitary state, and how territorial self-government is organized. However, in each country we find the local level, which represents the basic level of territorial self-government—the municipality (

Peková 2011). However, it should be added that, although there is a local level in each country, the range of public goods provided by municipalities is different. This is also confirmed by

Čebišová et al. (

1996), who states that there are significant differences between countries, especially in the performance of elected bodies at the municipal level. The elected body entrusts its executive bodies with the task of ensuring the competencies. The relationship between the central level of government and local self-government can be of various types (from the type when the state command to the type when the state does not interfere into the activities of local self-government) (

Peková 2004). In most countries, local self-government is organizationally independent of the central level of government, but is dependent on state funding. Mutual coordination between the two entities is therefore important for the effective functioning of local self-government. One of the theories that deals with the search for possibilities of optimal use of individual functions of public finances at individual levels is the theory of fiscal federalism. Especially in the developed countries of Europe, since the beginning of the 70s of the 20th century, the function of public finance respectively local self-government involved in the process of stabilizing the economy of the territory. Fiscal federalism works through the application of various instruments by the federal government, in particular federal taxes, subsidies, and subsequent financial transfers to the regions. The idea of fiscal federalism was the axis of the political debates that preceded the beginning of the process of economic integration in Western Europe in the late 1940s and early 1950s. This idea was also one of the key issues that always took place in the debate on the next stages of European integration (

Oręziak 2018).

(

Boye 2018) argues that, for reasons of efficiency, higher government should provide “clean” public goods, which are services that are available to all inhabitants, whether or not they contribute to the system—e.g., defense. Lower-level government should be responsible for services that bring benefit for local consumers. In such cases, positive externalities are generated.

McLure (

2001) in this context; however, he points to the “tax assignment problem”, e.g., at which level of government tax powers should be acquired.

Musgrave (

1959) suggested that the redistribution of income be assigned to the first government order. Therefore, corporate taxes and progressive the tax from personal income, the main instruments for revenues redistribution, are assigned to the state level. Taxes that have little or no impact on macroeconomic stability (e.g., sales tax and real estate tax) are assigned to sub-state level of government. This is also confirmed by

Table 1, where tax from personal income account for 24% of total taxation in OECD countries. The importance of direct and indirect taxation in the collection of revenues is also confirmed by

Myles (

2004), who states that these revenues generate 73% of revenues in the UK and 63% in Japan. The author further states that, in OECD countries, in 1991 income tax accounted for 11.6% of GDP.

Table 1 shows that for the period 2009 to 2018, income tax as % of GDP decreased slightly compared to 1991. These incomes reached the level of 1991 only in 2017 (

Table 1).

It follows from the above that, from the point of view of fiscal federalism, the allocation function of public finances can be considered key. Each developed country must decide to which level of public administration to allocate the competence to provide individual public services and subsequently allocate resources for this performance. There are no uniform and clear rules here, the specific solutions may differ significantly (

Medveď and Nemec 2011).

Lipták (

1999) notes, however, that tax jurisdiction at a lower level of government is associated with the risk of tax competition between territories. It could result in different levels of tax burden and thus cause migration of certain sections of the population or capital.

Pisár (

2003) notes, however, that the doubts raised by the theory of fiscal federalism do not mean that all functions must necessarily be centralized. Lower levels of government in all developed countries perform many functions, especially in the social field. From this point of view, the allocation function and the related principle of subsidiarity come to the fore, which emphasizes the need for public goods to be provided in accordance with the preferences of the population, who cover the costs of these goods through taxes or user fees.

Financial management in local self-government units has many definitions, which often complement each other. It is primarily a process of financial management that leads to the optimal implementation of public tasks that meet the needs of the local population. The financial management of local self-government is, therefore, one of the most important issues for the functioning of local self-government. It determines the correct use of funds in each local self-government, the correct performance of tasks and ensuring long-term socio-economic development in its territory (

Świrska 2016). The local self-government manages the available financial resources in accordance with the adopted principles related to the creation and use of financial resources and in accordance with the approved budget. Prior to the decentralization of public administration, funds were redistributed to local self-government directly from the state budget and were earmarked

Kapidani (

2015). However, according to

Bonfatti and Forni (

2019), decentralization has a direct impact on the well-being of the population. The results, which analyzed the budgets of Italian municipalities from 1999 to 2012, show that the reduction of the local budget deficit was achieved mainly by squeezing capital expenditures. The above research shows that the decline in capital expenditures may have an impact on the quality of life of the population, as capital expenditures are primarily focused on the investment activities of the municipality. Therefore, according to

Merkaj et al. (

2017), it is necessary to evaluate decentralization according to the specific needs of the country.

Dosmagambetova (

2014) states that the main advantage of decentralization at the level of local self-government is manifested in strengthening the influence of inhabitants, strengthening the principles of self-government and providing specific services through original and transferred competencies. He also confirm

Davulis and Slavinskaitė (

2012) who note that decentralization of public administration helps to increase economic efficiency by creating better conditions for the provision of public goods that meet the needs of consumers. Not only decentralization, but also the introduction of accrual accounting in individual public administration entities contributed to increasing the efficiency of the provision of public goods.

Christofzik (

2019) states that municipalities in Germany have gradually introduced accrual-based accounting systems. Although author notes that empirical evidence on the effects of such accounting is limited, but he believes that accrual accounting has changed the structure of local self-government budgets. According to

Cohen et al. (

2019), however, more attention needs to be paid to accrual accounting in the public sector and to avoid shortcomings that have occurred in the private sector. A better understanding of the financial conditions and policy factors that constitute obstacles, as well as the governance behavior of public administrations, should improve the quality of services provided to the population.

The economy of municipalities is governed by a financial plan (budget), which is created for a period of at least two years in advance. The budget of the municipality is defined by the objectives of the municipality and related financial operations (

Andrejovska and Pulikova 2018;

Hamalová et al. 2014). The budget must be prepared so that it is possible to carry out all activities related to the functioning of the municipality (

Dušek 2017).

Provazníková (

2009) note that during the financial year, there are inconsistencies between the budget and reality may be caused by organizational changes, changes in laws, or facts that were not known during the compilation of the budget. According to (

Peková 2011) the decisive share of revenues and expenditures in the budget is in the nature of non-repayable flows. The management of these funds can be characterized by the following relationship:

where

—the value of funds in the budget at the beginning of the budget period (e.g., balances from previous years)

P—the value of revenues

V—the value of expenditures

—the value of funds in the budget at the end of the budget period

If F2 > F1, a financial reserve is created for management in the next budget year

If F1 > F2, this means the use of past reserves or other resources to offset the annual budget balance

Kranecová (

2015) notes that, especially in the former post-communist countries, the powers of local self-government to influence their revenues are gradually increasing. The most common types of revenues of local self-government in Europe are tax revenues, transfers, subsidies, non-tax revenues. Traditionally, tax revenues have the biggest share. In the direction from Western Europe to Eastern Europe, the number of taxes that may affect regions or municipalities in some way is declining. This is also confirmed by

Richiedei and Tira (

2020) who note that the primary income for local self-government in Italy is income from the state and the region and revenues from personal income tax.

In addition, local self-governments may also have their own income from property and from local taxes, as well as from additional revenues, such as fines, profits from facility companies, or quarries and landfills. Moreover, according by

Kapidani (

2015), local authorities do not have adequate financial resources within their powers. They are still highly dependent on financial assistance from the central government, especially small local self-government. The author states that in 2012, 60% of local budgets in Albania were financed from more than 80% of the state budget. One of the reasons is the insufficient capacity of local self-government to collect their own revenues, especially property taxes and other taxes and local taxes. Municipalities in the Czech Republic also show a high dependence on income at the local level from the state. Tax revenues represent 55% of their revenues. Transfers from the national and regional level to municipalities budgets also remain an important tool (

Spacek and Dvorakova 2011). The influence of the state on the financing of local self-government is also mentioned in research by

Zelca (

2010), which showed that local self-government revenues in Latvia increased every year between 2006 and 2008 due to the annual increase of personal tax revenues. In 2009, however, the situation changed as the state proceeded with revenues consolidation, which was subsequently reflected in a decline in local self-government revenues

Ivanova and Kamols (

2013) add that in Latvia revenues from personal tax income accounted for an average of 85% of all local self-government tax revenues between 2009 and 2011. Local self-government tax revenues accounted for 61% in 2009 and even 63% in 2010 and 2011 from total revenues. Local self-government in Russia also show a high level of financial dependence on the financial decisions of the state government. According to the authors, a reduction in the financial dependence of local budget could be through an increase in non-tax revenues and the associated efficient management of property, but also a clear division of competences between central authorities and local self-government (

Shcherban et al. 2018). Revenues from the use of property as an option to increase local self-government revenues in Poland is also mentioned by

Dyk (

2012), but now in Poland the main sources of local self-government revenues are currently taxes from the state and fees. This statement is also confirmed by research

Świdyński (

2019) who showed that 26% of the current revenues of local self-government in Poland represented tax from personal income, 25% were grants from the state budget, 23% were revenues from municipal property, and 8% were revenues from other sources.

Hita et al. (

2011) states that another source of revenues for local self-government in Spain is income from urban development, which is revenues from land use. This income is part of capital expenditures. At the same time, author adds that local self-government has significantly more control over the use of capital expenditures than over the use of current expenditures. This is related to the fact that a big amount of current expenditures is earmarked (e.g., for employees’ wages, electricity and water supply, etc.).

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of the paper is to characterize and to compare the mechanism of creating revenues of the local self-government in the Slovak and Czech Republic and at the same time to analyze the relationships between individual groups of local revenues in the time period 2009–2018. In the analysis we follow the basic groups of municipal revenues: total revenues, current revenues, and capital revenues. Their structure and creation are discussed in

Section 4. We analyzed, in detail, individual groups of revenues within the current budget as well as within the tax revenues of municipalities. This is due to the fact that current revenues, but especially tax revenues of municipalities, present important factors in the development of municipalities. The reason for choosing these two countries was the fact that, until 1993, both countries were part of one country. Although the same model of public administration is used in both countries, the mechanism of financing local self-government shows certain specifics.

Articles evaluate all of the municipalities in Slovak Republic and in Czech Republic (we used the cumulative data). As a base, we used the data from the evaluation of the results of budget management of municipalities in Slovak Republic, state final account of territorial budgets of Czech Republic, and data from Slovak and Czech Statistical Office. For the purpose of comparison, we converted the data for Czech Republic to € on the basis of the CZK and € exchange rate, according to the National Bank of Slovak Republic exchange rate for the relevant year.

The trend analysis is used to analyze the obtained time series. The trend in time series can be described using trend functions and moving averages or moving medians. Trend modeling using trend functions is used, if the development of the time series corresponds to a certain function of time, e.g., linear, quadratic, exponential, S-curves, etc. (

Arlt et al. 2002).

The time series represented individual years in a time period 2009–2018. The time series

for

may be expressed by

, where

is a systematic component and represents a deterministic trend that can be expressed by the mathematical function of the time variable

, and

is a non-systematic component with white noise process properties. The analyzed time series are modeled with the linear trend line

, the exponential trend line

, the logarithmic trendline

, the 2nd order polynomial trend line

, and the power trendline

, for

. We estimate the parameters

,

, and

for each trendline and calculate

. The appropriate trend function is selected based on graphical analysis and interpolation criteria—the root mean square error (

), the mean absolute error (

), and the determination coefficient (

).

We search for a trend function that has minimum values of and , and maximum values of .

We conduct correlation analysis to examine the statistical dependence of tax income time series by analyzing statistical dependence between random components

of the examined time series. For the estimated trend functions, we correlate the residual values

given by

. The method suggested by

Hindls et al. (

2003) avoids the apparent correlation that may occur between mutually independent variables underlying the same trend. According to

Markechová et al. (

2011), the strength of linear dependence is measured by a sample correlation coefficient

:

where

,

are residual values for time series

,

.

4. Results and Discussion

Revenues of local budgets are defined in the terms of Slovak and Czech Republic within the framework of laws. In the Slovak Republic, it is act no. 582/2004

1 Coll., on budgetary rules of territorial self-government, and in the Czech Republic, it is act no. 250/2000

2 coll., on budgetary rules of territorial budgets. The detailed structure of individual revenues on the basis of these acts are shown in

Table 2.

4.1. The Mechanism of Revenues of Local Self-Government

In general, budget revenues are divided into two categories: current revenues and capital revenues. Current revenues present revenues that are regularly recurring and their volume can be predicted relatively well, unlike capital revenues, which are random revenues and consist mainly of revenues from the sale of municipal property.

Table 3 shows that, in both countries, current revenues are made up of three basic revenue categories. There is a slight difference in the revenue structure within each category.

Table 3 shows that, in both countries, current revenues are made up of three basic revenue categories. There is a slight difference in the income structure within each category. Almost 74% of the total volume of tax revenues are revenues from share tax in the Slovak municipalities and almost 85% in the Czech municipalities. The share tax in the conditions of Slovak municipalities is represented by the revenues from the tax of personal revenues, which is redistributed by the state to the level of municipalities on the basis of the regulation of the Slovak Government. This new system of financing municipalities, valid from 1 January 2005, strengthens the financial autonomy, transparency, stability, and responsibility of local authorities when deciding on the use of public resources to provide services to the inhabitants. The base of this process was the transition from providing subsidies from the state budget to the financing of competencies through tax revenues, so the share of revenues of self-governments increased. The most important criterion for the redistribution of this tax at the level of municipalities is the number of inhabitants residing in the municipality, which implies that municipalities, when drawing up their budgets, can approximately predict the volume of these funds. While Slovak Republic municipalities receive revenues from only one share tax, Czech Republic municipalities receive revenues from two types of state taxes.

Peková (

2011) states that taxes entrusted are types of taxes that are levied under national tax laws, but whose whole revenues go directly into the budget of municipalities. Shares taxes are taxes that are redistributed to the level of municipalities with a certain share.

Dvořák (

2017) notes that according to act no. 243/2000 Coll., on the budgetary determination of taxes are precisely specified revenues that are redistributed from the state to the local self-government in Czech Republic as the share taxes. These are following revenues: 20.83% share of the tax on the added value, 22.78% share of the tax of the personal income from dependent activities and functional benefits, 23.58% share of the personal income tax deducted at a special rate, 23.58% of the tax on personal income from self-employment, and 23.58% of the corporate income tax.

Čermák and Gürtler (

2014) note that, in 2008, a new legislation was adopted in the framework of budgetary tax determination in Czech Republic, which enlarged originally the only criterion of number of inhabitants in a municipality converted, according to coefficients of particular size categories by two other new criteria—a simple number of inhabitants and a cadastral acreage of the municipality. Another change that occurred in 2013 in the financing of local self-government in the Czech Republic is reported by

Lorenc and Kašpárková (

2014), who notes that the calculation of municipal tax revenues has changed by including another indicator—the number of children attending school or school facility in the municipality, and at the same time, new size groups of municipalities, were determined.

An equally important group of tax revenues are also revenues from local taxes and fees. In both countries these revenues belong to own revenues as they are collected by the municipality. In Slovak Republic, municipalities may collect eight different types of local taxes, but they must collect a local fee for construction waste and small construction waste. In Czech Republic, municipalities may collect seven different types of local fees and one tax—real estate tax (

Table 4).

Non-tax revenues represent, on average, 13% of current revenues of municipalities in Slovak Republic and 11% within the Czech Republic. These revenues mostly consist from revenues of own and business with municipal property. Municipalities most often rent their property. In addition, non-tax revenues also include administrative fees paid by inhabitants for providing services (for example, for register services, signature verification, etc.).

Municipalities in both countries receive grants and transfers from the state budget, and the vast majority of these are purpose-bound financial resources. These funds are provided to municipalities to finance the transferred competencies of state administration. By being purpose-bound by these funds, the state has the possibility to control them and, at the same time, ensures a certain standard of public service provided to the inhabitants. These revenues represent on average 29% of the total current revenues of the municipality in Slovak Republic and 27% in Czech Republic.

Capital revenues are predominantly purpose-bound for investment activities of municipalities and municipalities obtain them in both countries by selling their own property (which is very rare) or through capital purpose-bound subsidies intended for a specific investment activity.

4.2. Analysis of Total Revenues, Current Revenues, and Capital Revenues

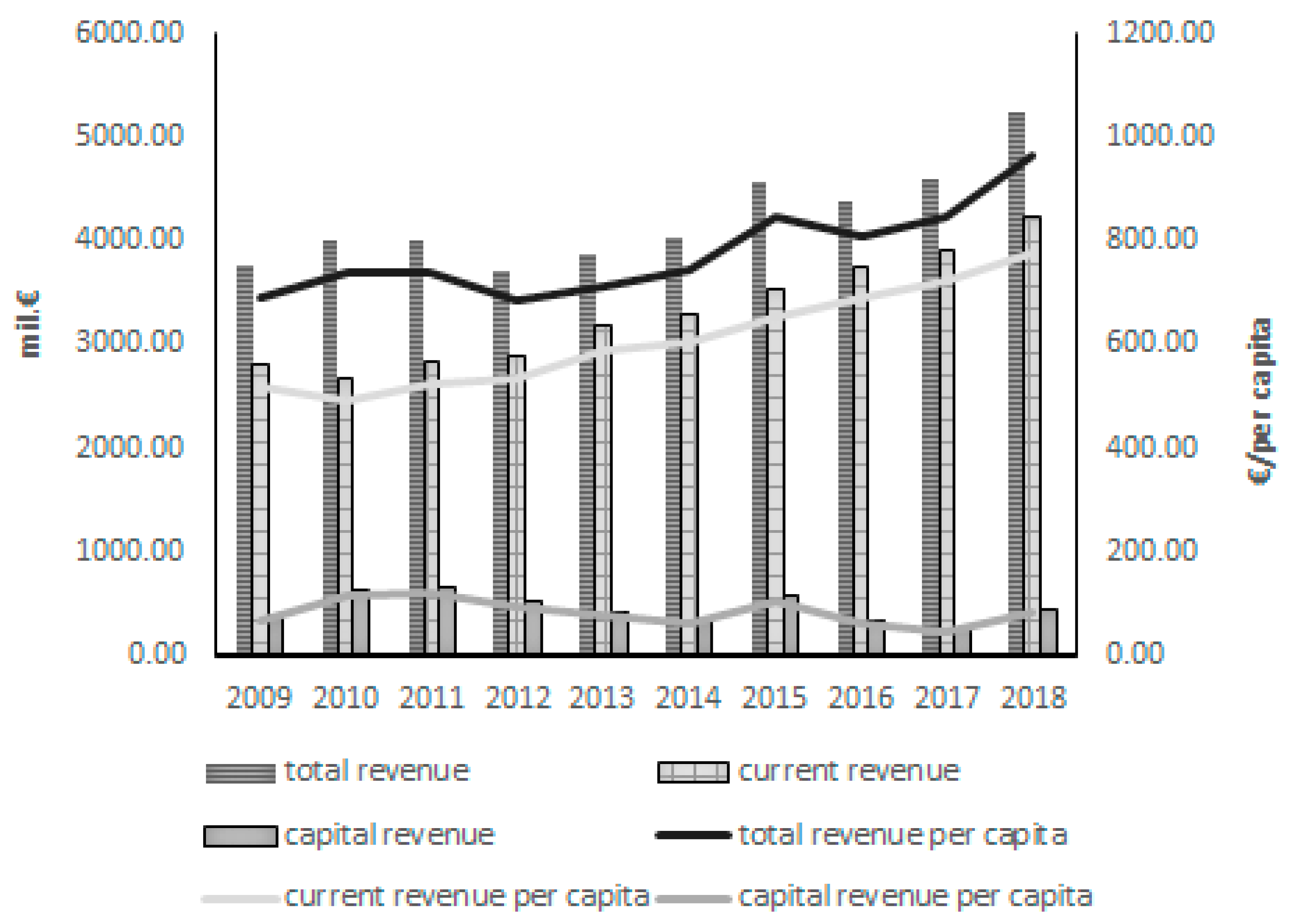

Total revenues of municipalities consist of current revenues and capital revenues. The development of total revenues of municipalities in the Slovak Republic during the analyzed period 2009–2018 showed a fluctuating trend (

Figure 1). There was a slight decrease in total revenues in 2011 (compared to 2010 it was 0.43%) and in 2012, when we recorded a significant decrease in total revenues of municipalities (a decrease was 7.52% compared to the previous year). In these years, the financial crisis has fully manifested itself, which has hit Europe, and has also had a significant impact on the financial management of local self-governments. In the following years, the total revenues of municipalities grew, except for 2016, when compared to the previous year, these revenues decreased by 4.17%. In per capita terms, total revenues ranged from €692.88 to €964.78, current revenues from €490.13 to €778.40 and capital revenues from €59.74 to €114.55.

Current revenues represent on average 75% of the total revenues of municipalities. Unlike total revenues, these revenues increased annually except for 2010 (a decrease by 5.06%). Overall, in 2018 the current revenues of municipalities increased by 1.5 times compared to 2009 (

Figure 1). This relatively balanced development of these revenues, as well as the actual increase, is due to the fact that these revenues consist mainly of revenues from the state budget in the form of a share tax. In addition, these revenues also include revenues directly from inhabitants of municipalities in the form of local taxes and local fees. A very small component of these revenues is non-tax revenues, which are obtained by municipalities for instance for renting their property. Capital revenues consist of revenues from the sale of movable and immovable property. These revenues represent on average 15% of the total revenues of municipalities. These revenues are random, which means that they are not predictable at the same amount each year as opposed to current revenues, which we can predict quite well. This randomness was also reflected in the fluctuating trend of these revenues over the analyzed time period. Municipalities received the highest capital revenues in 2011 and the lowest in 2017.

As in Slovak Republic, in Czech Republic the total revenues of municipalities in the analyzed time period showed a fluctuating trend. Total revenues decreased in the time period 2011–2013 and, subsequently, in 2016 (1.96% decrease compared with the previous year). In comparison with 2009 and 2018, the total revenues of municipalities increased by 29.7% (

Figure 2). Current revenues represent, on average, 97% of total revenues of municipalities. Compared to Slovak municipalities, the share of current revenues of total revenues is much higher. The development trend of this group of revenues is similar to the development of total revenues of municipalities, since the vast majority of total revenues present current revenues. In comparison with 2009 and 2018, current revenues of municipalities increased by 28.35%. Similar to the Slovak Republic, in the Czech Republic, capital revenues are among the random revenues that municipalities obtain by selling their property. In contrast to the Slovak municipalities, in comparison with 2009 and 2018, there is a significant decrease (double decrease) in these revenues between 2009 and 2018.

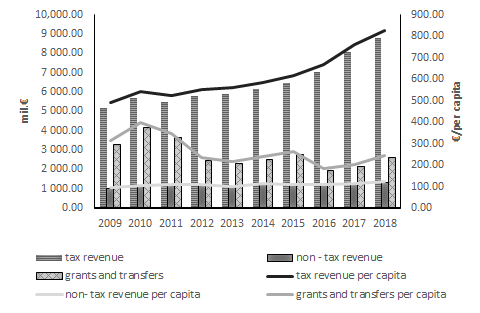

Current revenues consist of tax revenues, non-tax revenues, and grants and transfers. The mechanism for creating of individual revenues groups in both countries was presented in

Section 4.1. Except for 2010, tax revenues of Slovak municipalities recorded an annual increase. The decrease in tax revenues in 2010 compared with 2009 was 12.28%. However, between 2009 and 2018, we see an increase in these revenues by 58.46% (

Figure 3). In terms of per capita tax revenues of municipalities, it ranged between €261.44 and €471.60. The second category of current revenues are non-tax revenues. These revenues, in addition to business revenues, also comprise revenues from administrative fees paid by inhabitants for the provision of various services. Non-tax revenues represent, on average, 10% of total current revenues, and per capita these revenues ranged between €57.92 and €100.26.

The development of these revenues was similar to that of tax revenues, with the difference that we observe a decrease in these revenues in 2014 and 2016. However, between 2009 and 2018, the increase in this income group was much higher than the increase in tax revenues (increase by 66.45%). Municipalities receive grants and transfers primarily to ensure the transferred competencies from state administration. Unlike tax and non-tax revenues, these funds are purpose-bound. Except for 2011 and 2012, we are seeing an annual increase in these financial resources. Between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased 1.3 times. In terms of per capita, grants and transfers of municipalities ranged between €158.74 and €210.71. These yearly increases in this income group are related to the transfer of new competencies to municipalities that require personnel and material technical equipment. It is precisely to secure these areas that municipalities use financial resources in the form of grants and transfers (

Figure 3).

The correlation analysis proves the dependence of local self-government revenues on the state. This is also confirmed by

Table 5, which shows the higher dependence of current revenues on share taxes (

) as well as tax revenues on the share tax. Tax revenues of municipalities are highly dependent on share tax, which municipalities receive from the state (

). The development of revenues from share tax significantly influences the development of municipal tax revenues. These results of the correlation analysis also confirm that fiscal decentralization has not fulfilled its role. The growth of tax revenues of municipalities is directly dependent on revenues from share tax, which is redistributed by the state. It follows from the above that the financial management of municipalities depends on the development of the economy at the level of the national economy; the more funds the state manages to collect from tax from personal income, the more funds municipalities will receive. Any changes in the amount of the share tax significantly affect the tax revenues of municipalities. This is also confirmed by

Andrejovska and Pulikova (

2018),

Korenkova (

2016),

Vojtech et al. (

2019), and

Holubek et al. (

2014) who state that taxes are generally considered to be a relevant policy instrument that significantly affects tax policy outcomes through tax rates. Within the framework of local taxes, the dependence of these taxes on the revenues from the real estate tax is proved (

). The reason is that the real estate tax revenues are a relatively stable component of local taxes and are basically paid, not only by inhabitants for their houses and land, but also by business entities for the use of non-residential premises and land for business purposes.

Tax revenues of municipalities in the Czech Republic consist of a mix of share taxes, taxes entrusted, and local fees. In the analyzed time period, these revenues decreased only slightly in 2011 (compared with the previous year, it was 3.54%). However, between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased significantly by 1.7 times. In terms of per capita, these revenues were in the range €491.11–€824.02 (

Figure 4). Non-tax revenues of municipalities in the Czech Republic are generated similarly as in the Slovak Republic through revenues from ownership and business with municipal property, as well as from administrative fees. These revenues represented, on average, 11% of the total current revenues and, in the per capita, these revenues were in the range €97.81–€122.14. Unlike tax revenues, non-tax revenues showed a fluctuating trend. In the period 2009–2012, we observe their annual increase. In 2013 and 2015–2016, non-tax revenues of municipalities decreased. However between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased by 26.57%. Grants and transfers, unlike tax and non-tax revenues, decreased by 20.35% between 2009 and 2018. These revenues belong to the category of revenues, which go from the state to the level of municipalities, and in the analyzed time period they ranged between €182.05 and €395.89. Municipalities registered an increase in these revenues only in the years 2010, 2014, 2015, 2017–2018 (

Figure 4).

As in the case of Slovak municipalities, Czech municipalities also show a high dependence of their revenues on money from the state budget (

Table 6). Municipal tax revenues are highly dependent on share taxes and entrusted taxes (

). In addition the total current revenues are also dependent on grants and transfers (

), not only on tax revenues (

).

Moreover, in this case, the results of the correlation analysis show the shortcomings of fiscal decentralization. In comparison with Slovak municipalities, Czech municipalities get from the state a so-called tax mix. In practice, this means that while Slovak municipalities are dependent on the development of one tax, which in the case of its negative development significantly affects the tax revenues of municipalities, the revenues of Czech municipalities from the share tax are more stable. This is due to the fact that tax from personal income is part of the tax mix, as well as the tax on the added value, and corporate income tax, which significantly stabilizes the total volume of these revenues.

Unlike Slovak municipalities, local taxes of Czech municipalities are, to a lesser extent, dependent on real estate tax (). This is mainly due to the different countries’ legislation on real estate tax. The act in the Slovak Republic sets the land tax rate of 0.25%. The act determines the tax rate for arable land separately and the special tax rate also has permanent grassland. Their value is expressed in euros per m2 depending on the cadastral area or district in which the land is located. The act also defines the tax rate for gardens, building plots, built-up areas, and courtyards by population per m2. The Czech Republic has a defined tax rate based on the type of land regardless the number of the population of the territory.

When comparing the results of the correlation analysis in both countries, different dependencies were shown for some indicators. In the conditions of Slovak municipalities, the analysis showed a negative correlation between non-tax revenues and tax revenues, on the contrary, in the conditions of Czech municipalities, this correlation was positive. The differences were mainly due to the development of individual indicators, which entered into the correlation analysis. Tax revenues of Slovak municipalities grew continuously throughout the period and non-tax revenues decreased only in 2014 and 2016. A different development was recorded in Czech municipalities, when tax revenues grew every year except 2011, but non-tax revenues decreased every year since 2013. A similar scenario was also recorded in the correlation of non-tax revenues and share tax, as well as in the correlation of grants and transfers and tax revenues.

4.3. Analysis of Tax Revenues

Tax revenues are part of current revenues. The Slovak municipalities receive these revenues mainly from the state budget in the form of share tax and also from the inhabitants in the form of local taxes and fees.

Petrasova and Beresecka (

2012),

Fila et al. (

2015) state in their research that local tax revenues can be used as one of the effective tools of regional policy as the support of cultural and artistic events in the territory.

Before the fiscal decentralization, municipalities received revenues from mix share taxes. In 2005, the government of the Slovak Republic decided that the only share tax for municipalities would be the revenues from the tax of personal income. An analysis of share tax shows that this decision has brought an increase of these revenues to the municipalities. Except for 2010, revenues from the share tax increased annually. Between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased by 65% (

Figure 5). On the other hand, the municipalities’ dependence on the state budget remained, as revenues from the share tax are on average for 73.7% of their total tax revenues. However, in times of economic crisis, municipalities received fewer funds, as these revenues are tied to the economy of the state. At the time of economic development, revenues from the tax of personal income are growing, but it is questionable what impact potential recession respectively slowdown of the Slovak economy will have on the tax revenues of municipalities. On average, revenues from local taxes account for 26.2% of the total tax revenues of municipalities. Under the conditions of the Slovak Republic, the general rate of local taxes is determined by act no. 582/2004 Coll., on local taxes and local fees for municipal waste and small construction waste, but the specific rates are determined by the relevant municipal council. This system of creating taxes creates a comparative advantage for municipalities in terms of the attractiveness of the municipality for the lives of future inhabitants. A significant part of local taxes is real estate tax. On average, these revenues account for 16.9% of total tax revenues. This tax, like other local taxes, is a facultative tax, but all municipalities in Slovak Republic have it in their territory.

Municipalities in Czech Republic receive a share tax from several taxes collected at the state level as opposed to Slovak Republic. The development of these revenues increased annually except for 2011, when they decreased by 3.72% compared with the previous year. Between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased by 73.04% (

Figure 6). On average, these revenues account for 85.42% of total tax revenues. Municipalities in Czech Republic have the possibility to collected 7 local fees and 1 local tax. Municipalities implement them on the basis of generally binding regulations. These fees are administered by the municipal authority. The development of these revenues had a fluctuating trend. In 2011, 2013, 2016, and 2018 they had a downward trend. However, between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased by 51.8%. Local fees together with real estate tax accounted, on average, for 14.49% of total tax revenues. In the Czech Republic, real estate tax is collected on the basis of a separate act. Under the legislation, there are some differences within the real estate tax components. The act in the Slovak Republic determines the land tax rate of 0.25%. Czech Republic has a defined tax rate based on the type of land regardless the number of inhabitants in the territory. These revenues decreased in 2011 and 2013. Moreover, within these revenues, between 2009 and 2018, these revenues increased by 76.89%. On average, they created 5.67% of total tax revenues.

The results of our analyses are also confirmed by

Vavrek and Adamisin (

2018), who, in their research of the revenues part of municipal budgets in the Slovak and Czech Republics, note that although the state determines the amount of administrative fees without the possibility of their adjustment by the municipalities, it leaves them a certain freedom in determining the amount of local taxes and fees in both countries.

Using the trend function, we analyze the trend of municipality revenues for the period from 2009 to 2018. The trend, used to model the time series, is chosen based on the interpolation criteria. For each time series we choose a trend function with a minimum value of

and

and maximum value of

. Values of interpolation criteria for individual trend functions are given in

Table 7 for the Slovak Republic and in

Table 8 for the Czech Republic. The trend function selected for modeling the income time series is highlighted in the table.

The trend function points to the dynamics of changes in individual groups of municipal revenues as well as total municipal revenues. Through this function, we tried to capture the basic tendency of the development of selected indicators, so to determine their trend. We used trend modeling, using trend functions, because the selected models (2nd polynomial, power, logarithmic, linear) the best balance the time series in terms of the values of the dependent variable. Balancing time series using trend functions is one of the most frequently used methods in forecasting, with which we can capture the development trend of the studied phenomenon. We use the method to create short-term forecasts. From the results of the trend function, as well as from the analysis of individual revenues groups (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), we can state that, in the short term, under unchanged conditions, municipalities in both countries can expect growth of their revenues. The current economic changes (crisis due to the pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) will also significantly affect the financial management of municipalities in both countries. Both countries are open economies, which in practice means that the national economies of both countries will be significantly negative affected. These negative effects will also be reflected in relation to municipalities, as municipalities in both countries are dependent on revenues from the state budget, which was confirmed by our analysis. For this reason, it will be necessary and interesting to take these changes into account in further analyses of financial indicators of municipalities.