An Examination of Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the Moderating Role of Supervisory Support: Evidence from the Field

Abstract

:1. Introduction

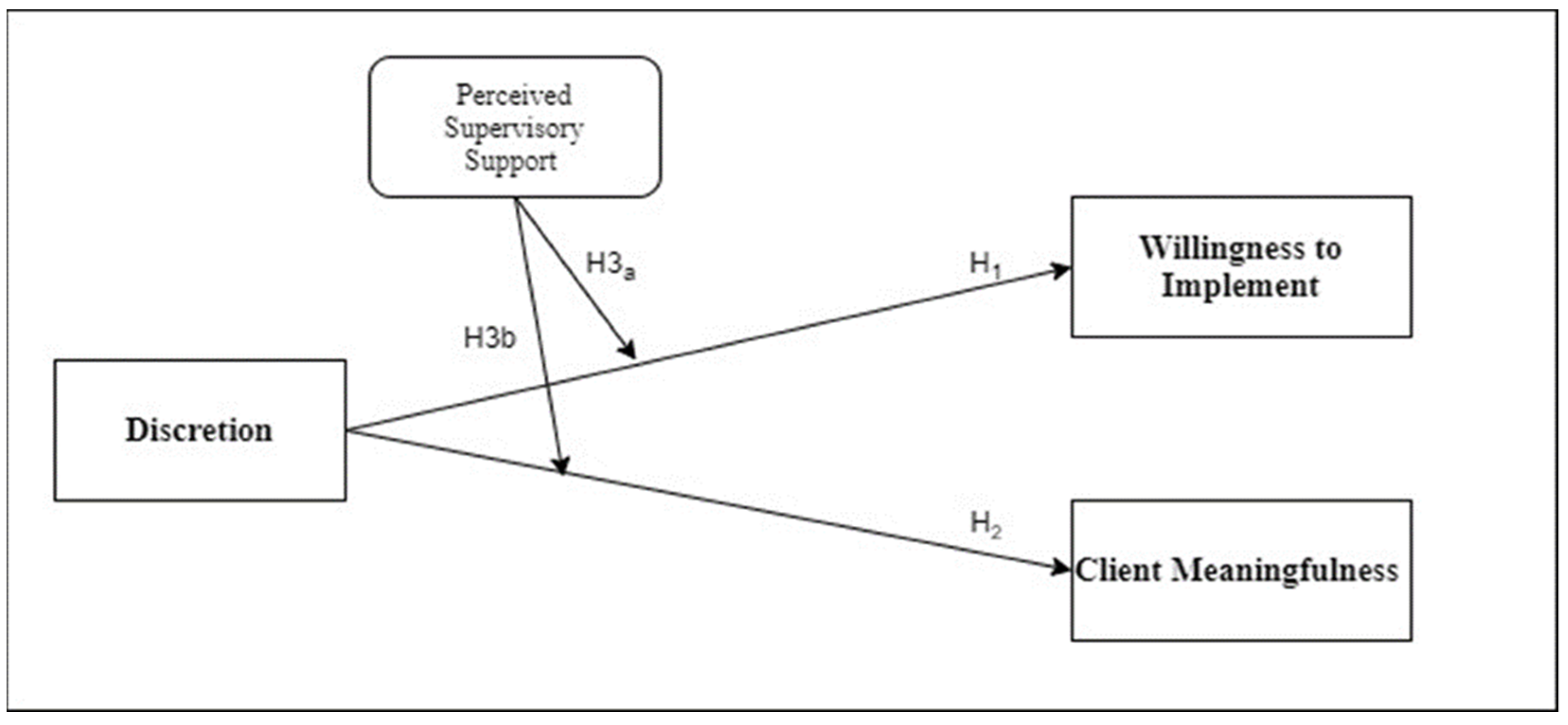

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Discretion

2.2. Client Meaningfulness

2.3. Willingness to Implement

2.4. The Moderating Role of Perceived Supervisory Support

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Sampling

3.2. Demographic Analysis of the Respondents

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis Method

3.5. Common Method Variance

3.6. Measurement Model

3.7. Structural Model: Hypothesis Testing

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Significant of This Study and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Halbusi, Hussam, Kent A. Williams, Hamdan O. Mansoor, Mohammed Salah Hassan, and Fatima Amir Hamid. 2019. Examining the Impact of Ethical Leadership and Organizational Justice on Employees’ Ethical Behavior: Does Person–Organization Fit Play a Role? Ethics & Behavior 30: 514–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James C., and David W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin 103: 411–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, Murray R., Michael K. Mount, and Ning Li. 2013. The Theory of Purposeful Work Behavior: The Role of Personality, Higher-Order Goals, and Job Characteristics. Academy of Management Review 38: 132–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, Michael B., and Eric Plutzer. 2012. Evolution, Creationism, and the Battle to Control America’s Classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Donald J., and Kenneth Culp Davis. 1970. Discretionary Justice: A Preliminary Inquiry. American Sociological Review 35: 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradley, Greta, Lambert Engelbrecht, and Staffan Höjer. 2010. Supervision: A Force for Change? Three Stories Told. International Social Work 53: 773–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, John, and Scott Gates. 2002. Working, Shirking and Sabotage: Bureaucratic Response to a Democratic Public. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Gene A. 2005. In the Eye of the Storm: Frontline Supervisors and Federal Agency Performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15: 505–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkin, Evelyn Z. 1997. Inside the Welfare Contract: Discretion and Accountability in State Welfare Administration. Social Service Review 71: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Jeremy F. 2013. Moderation in Management Research: What, Why, When, and How. Journal of Business and Psychology 29: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, Robert F. 2010. The Oxford Handbook of American Bureaucracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Florence Stinglhamber, Christian Vandenberghe, Ivan L. Sucharski, and Linda Rhoades. 2002. Perceived Supervisor Support: Contributions to Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Retention. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 565–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Kathryn. 2011. ‘Street-Level Bureaucracy’ Revisited: The Changing Face of Frontline Discretion in Adult Social Care in England. Social Policy & Administration 45: 221–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdeji, Irma, Ana Jovicic-Vukovic, Snjezana Gagic, and Aleksandra Terzic. 2016. Cruisers on the Danube—The Impact of LMX Theory on Job Satisfaction and Employees’ Commitment to Organization. Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic, SASA 66: 401–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Tony. 2016. Professional Discretion in Welfare Services. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Tony. 2020. Street-Level Bureaucrats: Discretion and Compliance in Policy Implementation. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazmand, Ali. 2019. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Henry E. 1939. “Lewin’s” topological” psychology; an evaluation. Psychological Review 46: 517–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gofen, Anat. 2019. Levels of Analysis in Street-Level Bureaucracy Research. In Research Handbook on Street-Level Bureaucracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 336–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodnow, Frank J. 2017. Politics and Administration. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, Nora, and Ann E. MacEachron. 2012. Managing Child Welfare in Turbulent Times. Social Work 58: 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2019. Multivariate Data Analysis. Andover: Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, Harry H. 1976. Modern Factor Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrits, Gitte Sommer. 2019. Street-Level Bureaucracy Research and Professionalism. In Research Handbook on Street-Level Bureaucracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Michael J., and Peter L. Hupe. 2014. Implementing Public Policy: An Introduction to the Study of Operational Governance. Los Angeles and Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Michael, and Frédéric Varone. 2021. Discretion, Rules and Street-Level Bureaucracy. The Public Policy Process, 246–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupe, Hill. 2016. Understanding Street-Level Bureaucracy. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hupe, Hill. 2019. Research Handbook on Street-Level Bureaucracy: The Ground Floor of Government in Context. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, Lars E. 2019. Negotiated Discretion: Redressing the Neglect of Negotiation in ‘Street-Level Bureaucracy’. Symbolic Interaction 42: 513–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, Anuradha, and Rhiannon McCluskey. 2018. The Art of ‘Bureaucraft’: Why and How Bureaucrats Respond to Citizen Voice, Making All Voices Count. Research Briefing: IDS. [Google Scholar]

- Kadushin, Alfred, and Daniel Harkness. 2014. Supervision in Social Work. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keulemans, Shelena, and Sandra Groeneveld. 2019. Supervisory Leadership at the Frontlines: Street-Level Discretion, Supervisor Influence, and Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Attitude towards Clients. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30: 307–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khine, Myint Swe. 2013. Structural Equation Modeling Approaches in Educational Research and Practice. Application of Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research and Practice 7: 277–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosar, Kevin R. 2011. Street Level-Bureaucracy: The Dilemmas Endure. Public Administration Review 71: 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottke, Janet L., and Clare E. Sharafinski. 1988. Measuring Perceived Supervisory and Organizational Support. Educational and Psychological Measurement 48: 1075–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladany, Nicholas, Deborah Lehrman-Waterman, Max Molinaro, and Bradley Wolgast. 1999. Psychotherapy Supervisor Ethical Practices. The Counseling Psychologist 27: 443–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberherr, Eva. 2019. Street-Level Bureaucracy Research and Accountability beyond Hierarchy. In Research Handbook on Street-Level Bureaucracy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 223–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsky, Michael. 2010. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Robert, and Jeffrey Glanz. 1992. Bureaucracy and Professionalism: The Evolution of Public School Supervision. History of Education Quarterly 32: 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, Scott B., and Philip M. Podsakoff. 2012. Common Method Bias in Marketing: Causes, Mechanisms, and Procedural Remedies. Journal of Retailing 88: 542–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Peter J. 1999. Fostering Policy Learning: A Challenge for Public Administration. International Review of Public Administration 4: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Peter J. 2003. Policy Design and Implementation. Handbook of Public Administration, 223–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Peter. J., and C. Winter. 2007. Politicians, Managers, and Street-Level Bureaucrats: Influences on Policy Implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19: 453–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard-Moody, S., and M. Musheno. 2000. State Agent or Citizen Agent: Two Narratives of Discretion. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10: 329–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard-Moody, Steven, and Shannon Portillo. 2010. Street-Level Bureaucracy Theory. Oxford Handbooks Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazmanian, Daniel A., and Paul A. Sabatier. 1989. Implementation and Public Policy: With a New Postscript. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, Kenneth J., and Laurence J. O’Toole. 2002. Public Management and Organizational Performance: The Effect of Managerial Quality. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 21: 629–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metselaar, Erwin Eduard. 1997. Assessing the Willingness to Change: Construction and Validation of the DINAMO. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, November 28. Available online: https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/assessing-the-willingness-to-change-construction-and-validation-o (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Meyers, Marcia, and Susan Vorsanger. 2007. Street-Level Bureaucrats and the Implementation of Public Policy. In Handbook of Public Administration: Concise Paperback Edition. Newcastle upon Tyne: sage, pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Abdul-Rahim. 2021. Discretion on the Frontlines of the Implementation of the Ghana School Feeding Programme: Street-Level Bureaucrats Adapting to Austerity in Northern Ghana. Public Administration and Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musheno, Michael C., and Steven Maynard-Moody. 2009. Cops, Teachers, Counselors: Stories from the Front Lines of Public Service. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, Dennis J., Steven Maynard-Moody, and Paula Wright. 1984. Measuring Degrees of Successful Implementation. Evaluation Review 8: 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccucci, Norma. 2005. How Management Matters: Street-Level Bureaucrats and Welfare Reform. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan Michael Becker. 2015. SmartPLS. Boenningstedt: Scientific Research Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Saetren, Harald. 2005. Facts and Myths about Research on Public Policy Implementation: Out-of-Fashion, Allegedly Dead, But Still Very Much Alive and Relevant. Policy Studies Journal 33: 559–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandfort, Jodi. 2000. Moving Beyond Discretion and Outcomes: Examining Public Management from the Front Lines of the Welfare System. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10: 729–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarstedt, Marko, Christian M. Ringle, and Joseph F. Hair. 2017. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Handbook of Market Research, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafritz, Jay M., and Ott J. Steven. 2001. Classics of Organization Theory. Fort Worth: Harcourt College Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, Lars. 2012. Policy Alienation of Public Professionals: The Construct and Its Measurement. Public Administration Review 72: 516–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, Lars, and Victor Bekkers. 2014. Policy Implementation, Street-Level Bureaucracy, and the Importance of Discretion. Public Management Review 16: 527–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, Lars, Bram Steijn, and Victor Bekkers. 2012. Explaining the Willingness of Public Professionals to Implement Public Policies: Content, Context and Personality Characteristics. Public Administration 90: 716–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visser, E. Lianne, and Peter M. Kruyen. 2021. Discretion of the Future: Conceptualizing Everyday Acts of Collective Creativity at the Street-Level. Public Administration Review xx: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, Kathryn Conley, Hyucksun Shin, and John Poertner. 2002. Transfer of Training. Journal of Health & Social Policy 15: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Woodrow. 1887. The Study of Administration. Political Science Quarterly 2: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Robert. 2006. Supervision and the Street-Level Bureaucrat. Paper presented at Annual Conference of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA, USA, August 31–September 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huan, Ling Yang, Robert Walker, and Yean Wang. 2020. How to Influence the Professional Discretion of Street-Level Bureaucrats: Transformational Leadership, Organizational Learning, and Professionalization Strategies in the Delivery of Social Assistance. Public Management Review 22: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items Labeled | Items Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discretion | DISC1 | 0.703 | 0.705 | 0.818 | 0.534 |

| DISC2 | 0.850 | ||||

| DISC4 | 0.565 | ||||

| DISC5 | 0.777 | ||||

| DISC6 | 0.766 | ||||

| Willingness to Implement | WIITP1 | 0.874 | 0.914 | 0.936 | 0.745 |

| WIITP2 | 0.892 | ||||

| WIITP3 | 0.775 | ||||

| WIITP4 | 0.857 | ||||

| Client Meaningfulness | CLITMEAN2 | 0.874 | 0.912 | 0.938 | 0.791 |

| CLITMEAN3 | 0.904 | ||||

| CLITMEAN4 | 0.883 | ||||

| CLITMEAN5 | 0.872 | ||||

| Perceived Supervisory Support | PSUPSP1 | 0.874 | 0.961 | 0.966 | 0.719 |

| PSUPSP2 | 0.861 | ||||

| PSUPSP3 | 0.888 | ||||

| PSUPSP4 | 0.794 | ||||

| PSUPSP5 | 0.834 | ||||

| PSUPSP6 | 0.832 | ||||

| PSUPSP7 | 0.894 | ||||

| PSUPSP8 | 0.843 | ||||

| PSUPSP9 | 0.845 | ||||

| PSUPSP10 | 0.846 |

| Client Meaningfulness | Discretion | Perceived Supervisor Support | Willingness to Implement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client Meaningfulness | ||||

| Discretion | 0.37 | |||

| Perceived Supervisory Support | 0.353 | 0.387 | ||

| Willingness to Implement | 0.403 | 0.364 | 0.276 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std Beta | Std Error | t-Value | p-Value | BCI 95% LL | BCI 95% UL | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||||||

| H1 | Discretion -> Client Meaningfulness | 0.305 | 0.071 | 4.290 | 0.000 | 0.153 | 0.400 | Significant |

| H2 | Discretion -> Willingness to Implement | 0.338 | 0.060 | 5.595 | 0.000 | 0.213 | 0.418 | Significant |

| Interaction Effect | ||||||||

| H3a | Discretion*PSSP-> Willingness to Implement | 0.055 | 0.069 | 0.808 | 0.210 | −0.061 | 0.157 | Non-Significant |

| H3b | Discretion*PSSP -> Client Meaningfulness | 0.094 | 0.056 | 1.690 | 0.046 | 0.084 | 0.187 | Significant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, M.S.; Raja Ariffin, R.N.; Mansor, N.; Al Halbusi, H. An Examination of Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the Moderating Role of Supervisory Support: Evidence from the Field. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030065

Hassan MS, Raja Ariffin RN, Mansor N, Al Halbusi H. An Examination of Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the Moderating Role of Supervisory Support: Evidence from the Field. Administrative Sciences. 2021; 11(3):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030065

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Mohammed Salah, Raja Noriza Raja Ariffin, Norma Mansor, and Hussam Al Halbusi. 2021. "An Examination of Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the Moderating Role of Supervisory Support: Evidence from the Field" Administrative Sciences 11, no. 3: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030065

APA StyleHassan, M. S., Raja Ariffin, R. N., Mansor, N., & Al Halbusi, H. (2021). An Examination of Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Discretion and the Moderating Role of Supervisory Support: Evidence from the Field. Administrative Sciences, 11(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030065