Perceived Organizational Support, Coworkers’ Conflict and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflict

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

2.2. Perceived Organizational Support

2.3. Coworkers’ Conflict

2.4. Work-Family Conflict as a Mediator

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measures

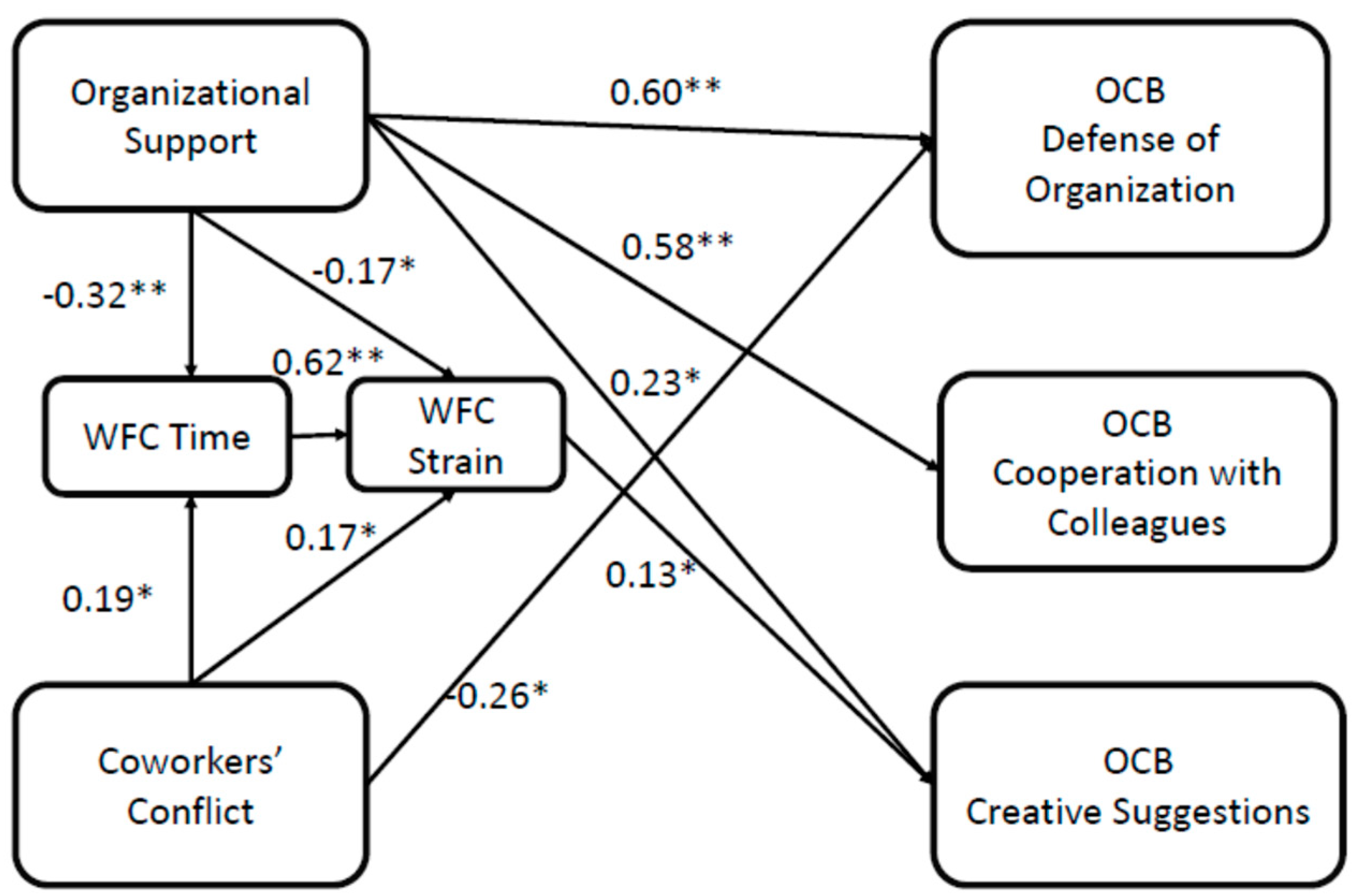

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Ishfaq, and Muhammad Musarrat Nawaz. 2015. Antecedents and outcomes perceived organizational support: A literature survey approach. Journal of Management Development 34: 867–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, James L. 2007. AMOS. version 16.0.1. Spring House: Amos Development Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach, Samuel B., Peter Bamberger, and Sharon Conely. 1991. Work-Home conflict among nurses and Engineers: Mediating the impact of stress on burnout and satisfaction at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior 12: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, Elpine De Boer, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2003. Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and absence frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior 62: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, Chester. 1968. The Functions of the Executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. First published 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos, António Virgílio, Mirlene Maria Siquiera, and Ana Cristina Gomes. 2014. Cidadania Organizacional. In Novas Medidas de Comportamento Organizacional. Edited by Mirlene Maria Siqueira. Porto Alegre: Artemed, pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, Eeman, Rabindra Kumar Pradhan, and Hare Ram Tewari. 2017. Impact of organizational citizenship behavior on job performance in Indian healthcare industries: The mediating role of social capital. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 66: 780–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, Whitney, Audrey Laporte, Liane Ginsburg, Adrian Rohit Dass, Raisa Deber, Andrea Baumann, Lisa Cranley, Ivy Bourgeault, Janet Lum, Brenda Gamble, and et al. 2018. Relationships between work outcomes, work attitudes and work environments of health support workers in Ontario long-term care and home and community care settings. Human Resources for Health 16: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, Whitney, Audrey Laporte, Raisa Deber, Andrea Baumann, and Brenda Gamble. 2013. The evolving role of health care aides in the long-term care and home and community care sectors in Canada. Human Resourses for Health 11: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blakely, Gerald. L., Martha C. Andrews, and Robert Moorman. 2005. The moderating effects of equity sensitivity on the relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology 20: 259–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, James S., Mark W. Johnston, and Joseph F. Hair. 1997. Role stress, work-family conflict and emotional exhaustion: Inter-relationships and effects on some work-related consequences. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 17: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bragger, Jennifer DeNicolis, Ofelia Rodriguez-Srednick, Eugene J. Kutcher, Lisa Indovino, and Erin Rosner. 2005. Work-family conflict, work-family culture, and organizational citizenship behavior among teachers. Journal of Business and Psychology 20: 303–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, Wendy, Jennifer Martin, Louis C. Buffardi, and Carol Erdwins. 2002. Work-family conflict, perceived organizational support, and organizational commitment among employed mothers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 7: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, Dan S., In-Sue Oh, Christopher M. Berry, Ning Li, and Richard G. Gardner. 2011. The five-factor model of personality traits and organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 1140–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chughtai, Aamir Ali, and Sohail Zafar. 2006. Antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment among pakistani university teachers. Applied HRM Reserach 11: 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu, Carsten K., and Laurie R. Weingart. 2003a. A contingency theory of task conflict and performance in groups and organizational teams. In International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork and Cooperative Working. Edited by Michael A. West, Dean Tjosvold and Ken Smith. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 150–66. [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu, Carsten K., and Laurie R. Weingart. 2003b. Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 741–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, Frank R., Lindred Greer, and Karen A. Jehn. 2012. The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 97: 360–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands—Resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimas, Isabel Cristina Dórdio. 2007. (Re)pensar o Conflito Intragrupal: Níveis de Desenvolvimento e Eficácia. (Dissertação de Doutoramento não Publicada). Coimbra: Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação de Coimbra. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, Robert, Robin Huntington, Steven Hutchison, and Debora Sowa. 1986. Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 500–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, Sharon, Hang-Yue Ngo, and Steven Lui. 2005. The effects of work stressors, perceived organizational support, and gender on work-family conflict in Hong Kong. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 22: 237–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, Stephen J., Michael K. Mount, and Rosemary L. Jamison. 1990. Employer supported child care, work/family conflict, and absenteeism: A field study. Personnel Psychology 44: 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, Ana Rita, Ana Galvão, Susana Escanciano, Marco Pinheiro, and Maria José Gomes. 2018. Stress e engagement na profissão de enfermagem: Análise de dois contextos internacionais. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, Jeffrey H., and Nicholas J. Beutell. 1985. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review 10: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, Sait, Omer Turunc, and Mazium Celik. 2012. The impact of perceived organizational support on work-family conflict: Does role overload have a mediating effect? Economic and Industrial Democracy 34: 145–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjali, Hamid Reza, and Meysam Salimi. 2012. An investigation on the effect of organizational citizenship behaviors (ocb) toward customer-orientation: A case of nursing home. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 57: 524–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammer, Leslie B., Ellen Ernst Kossek, W. Kent Anger, Todd Bodner, and Kristi L. Zimmerman. 2010. Clarifying work-family intervention processes: The roles of work-family conflict and family supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology 96: 134–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hui, Chun, Dennis W. Organ, and Karen Crooker. 1994. Time pressure, Type A syndrome, and organizational citizenship behavior: A laboratory experiment. Psychological Reports 75: 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, Karen. 1995. A multidimensional examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 256–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Zhang. 2013. A study on the relationship between management team conflict and organizational citizenship behavior in colleges and universities: The mediating effect of organizational justice. Paper presented at the Proceedings of International Conference on Management Science and Engineering 20th Annual Conference, Harbin, China, July 17–19; pp. 1427–32. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=andarnumber=6586458 (accessed on 4 May 2019).

- Kacmar, Michele, Daniel Bachrach, Kenneth Harris, and David Noble. 2012. Exploring the role of supervisor trust in the associations between multiple sources of relationship conflict and organizational citizenship behavior. The Leadership Quarterly 23: 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapela, D. Tungisa, and S. Pohl. 2020. Organizational support, leader membership exchange and social support as predictors of commitment and organizational citizenship behaviour: Poverty as moderator. Pratiques Psychologiques 26: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Daniel, and Robert L. Kahn. 1978. The Social Psychology of Organizations. New York: Wiley. First published 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek, Erns, and Cynthia Ozeki. 1998. Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology 83: 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, James N., Robert Eisenberger, Michael T. Ford, Louis C. Buffardi, Kathleen A. Stewart, and Cory S. Adis. 2017. Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management 43: 1854–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, Susan J. 2000. Added benefits: The link between work-life benefits and organizational citizenship behaviour. Academy of Management Journal 43: 801–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Szu-Yin, Hsien-Chun Chen, and I-Heng Chen. 2016. When perceived welfare pratices leads to organizational citizenship behavior. Asia Pacific Management Review 21: 204–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, Eeman, Rabindra Kumar Pradhan, Hare Ram Tewari, and Lalatendu Kesari Jena. 2014. Organizational citizenship behavior, job performance and HR practices: A relational perspective. Management and Labour Studies 39: 449–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Russell A., Cathleen A. Swoody, and Janet L. Barnes-Farrell. 2011. Work hours and work-family conflict: The double-edged sword of involvement in work and family. Stress and Health 28: 234–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Ali H. 2014. Perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior: The case of Kuwait. International Journal of Business Administration 5: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netermeyer, Richard, James Boles, and Robert McMurrian. 1996. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 400–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, Sharon. 2018. Organizational citizenship behavior: Sensitization to an organizational phenomenon. Journal of Nursing Management 26: 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Alicia, and Hugo Uribe Delgado. 2005. Las dimensiones de personalidad como predictores de los comportamientos de ciudadanía organizacional. Estudos de Psicologia 10: 157–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, Dennis W., and Katherine Ryan. 1995. A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology 48: 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, Dennis W., Philip M. Podsakoff, and Scott B. MacKenzie. 2006. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., and Scott B. MacKenzie. 1997. Impact of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: A review and suggestions for future research. Human Performance 10: 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical view of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, Nathan, Philip. M. Podsakoff, Scott B. Mackenzie, Timothy Maynes, and Trevor Spoelma. 2014. Consequences of unit-level organizational citizenship behaviors: A review and recommendations for future research. Journal of Organziational Behavior 35: 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Hina, Nasir Mehmood, Afsheen Fatima, and Iffat Rasool. 2018. Wishful thinking and professional commitment: The forebears of organizational citizenship behavior. UW Journal of Management Sciences 1: 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shanker, Meera. 2018. Organizational citizenship behavior in relation to employees’ intention to stay in Indian organizations. Business Process Management Journal 24: 1355–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. Ann, Dennis W. Organ, and Janet P. Near. 1983. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. Journal of Applied Psychology 68: 653–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Cynthia A., Laura L. Beauvais, and Karen Lyness. 1999. When work-family benefits are not enough: The influence of work-family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 54: 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, Maria, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2010. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology 36: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tinti, Joel Adame, Luciano Venelli-Costa, Almir Martins Vieira, and Alexandre Cappellozza. 2017. O impacto das políticas e práticas de recursos humanos sobre os comportamentos de cidadania organizacional. Brazilian Business Review 14: 636–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, Cynthia A., Jeanine K. Andreassi, and David J. Prottas. 2005. Work-Family Culture: Key to Reducing Workforce-Workplace Mismatch? In Work, Family, Health, and Well-Being. Edited by Suzanne M. Bianchi, Lynne M. Casper and Rosalid Bukow King. New York: Routledge, pp. 117–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tompson, Holly B., and Jon M. Werner. 1997. The impact of role conflict/facilitation on core and discretionary behaviors: Testing a mediated model. Journal of Management 23: 572–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, Linn, and Jeffrey A. LePine. 1998. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal 41: 108–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, Fred O., Russel Cropanzano, and Barry M. Goldman. 2011. How leader-member exchange influences effective work behaviors: Social exchange and internal-external efficacy perspectives. Personnel Psychology 64: 739–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, Sandy, Lynn M. Shore, William H. Bommer, and Lois E. Tetrick. 2002. The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology 87: 590–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. OCB—Defense of the organizational image | 3.89 | 1.31 | - | ||||||

| 2. OCB—Cooperation with coworkers | 2.95 | 1.15 | 0.36 ** | - | |||||

| 3. OCB—Creative solutions | 3.15 | 1.83 | 0.41 ** | 0.31 ** | - | ||||

| 4. POS—Perceived organizational support | 3.57 | 0.78 | 0.47 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.42 ** | - | |||

| 5. Coworkers’ conflict | 3.41 | 0.78 | 0.39 ** | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.17 | - | ||

| 6. Work-family conflict (time) | 3.12 | 1.23 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.31 ** | 0.30 ** | - | |

| 7. Work-family conflict (strain) | 3.11 | 1.45 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.33 ** | 0.29 | 0.41 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrade, C.; Neves, P.C. Perceived Organizational Support, Coworkers’ Conflict and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflict. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010020

Andrade C, Neves PC. Perceived Organizational Support, Coworkers’ Conflict and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflict. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrade, Cláudia, and Paula C. Neves. 2022. "Perceived Organizational Support, Coworkers’ Conflict and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflict" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010020

APA StyleAndrade, C., & Neves, P. C. (2022). Perceived Organizational Support, Coworkers’ Conflict and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Mediation Role of Work-Family Conflict. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010020