Investigating the Relationship between Experience, Well-Being, and Loyalty: A Study of Wellness Tourists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourist Experience in Tourism and Hospitality Industry

2.2. Tourism Experience and Well-Being

2.3. Spa/Wellness Tourism

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.5. Conceptual Framework

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Instrument/Measures

3.2.1. Autonomy

3.2.2. Intrinsic Motivation

3.2.3. Experience

3.2.4. Positive Emotions

3.2.5. Life Satisfaction

3.2.6. Loyalty

3.3. Study Settings, Sampling, and Data Collection

3.4. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Reliability and Demographic Results

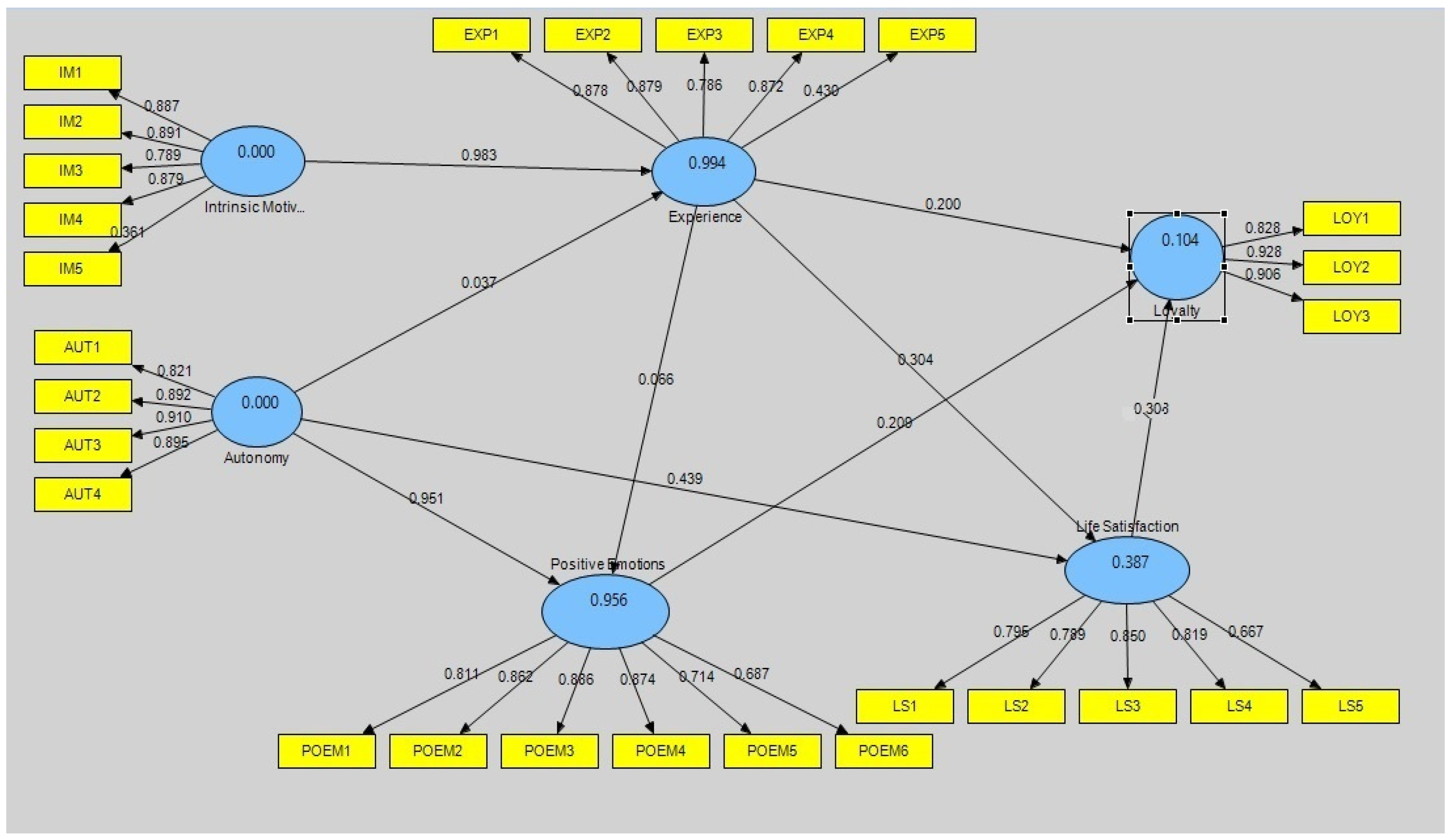

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

4.4. Mediation Results

4.5. Moderating Results

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Directions for Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ábrahám, Júlia, Attila Velenczei, and Attila Szabo. 2012. Perceived Determinants Well-being and enjoyment level of leisure activities. Leisure Science 34: 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, Joaquin, and Magdalena Cladera. 2009. Analyzing the effect of satisfaction and previous visits on tourist intentions to return. European Journal of Marketing 43: 670–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, Inoormaziah, and Jennifer Kim Lian Chan. 2010. Health and Spa Tourism Business: Tourists’ profiles and motivational factors. Health, Wellness and Tourism: Healthy Tourism Healthy Business 9: 24. [Google Scholar]

- Backman, Sheila J., Yu-Chih Huang, Chun Chu Chen, Hsiao Yun Lee, and Jen-Son Cheng. 2022. Engaging with restorative environments in wellness tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, Seyhmus, James Busser, and Lisa Cain. 2019. Impact Experience Emotional Well-being and loyalty. Journal of Hospitality Marketing Management 8: 427–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeho, Alison J., and Richard C. Prentice. 1997. Conceptualizing the Experiences of Heritage Tourists: A Case Study of New Lanark World Heritage Village. Tourism Management 18: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Piervito, Giulio M. Cappelletti, Edgardo C. Sica, and Roberta Sisto. 2020. Stakeholder Involvement to Improve Accessibility in a Protect Natural Area: A Case Study. Paper presented at the Le Scienze Merceologiche Nell’era 4.0, the Atti del XXIX Congresso Nazionale di Scienze Merceologiche, Salerno, Italy, February 13–14; Edited by B. Esposito, O. Malandrino, M. R. Sessa and D. Sica. Milano: Franco Angeli. ISBN 978-88-351-0527-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bigné, Enrique, Luisa Andreu, and Jurgen Gnoth. 2005. The theme park experience analyzes pleasure, arousal, and satisfaction. Tourism Management 26: 833–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkhorst, Esther, and Teun Den Dekker. 2009. Agenda for Co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality and Marketing Management 18: 311–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasche, Gerhard, Valentin Leibetseder, and Wolfgang Marktl. 2010. Association of spa therapy with improved psychological symptoms of occupational burnout: A pilot study. Complementary Medical Research 17: 132–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, Alan D. 2008. Motivations, attitudes, and beliefs. In Handbook of Hospitality Marketing Management. Edited by Haemoon Oh and Abraham Pizam. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, pp. 239–66. [Google Scholar]

- Campón-Cerro, Ana María, José Manuel Hernández-Mogollón, and Helena Alves. 2017. Sustainable improvement of competitiveness in rural tourism destinations: The Quest for Tourist Loyalty in Spain. Journal of Destinations and Marketing Management 6: 252–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa-López, Conrado, Maurício Carvache-Franco, and Wilmer Carvache-Franco. 2021. Perceived Value and Its Predictive Relationship with Satisfaction and Loyalty in Ecotourism: A Study in the Posets-Maladeta Natural Park in Spain. Sustainability 13: 7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruthers, Cinthya P., and Colleen D. Hood. 2007. Building a life meaning through Therapeutic Recreation: The Leisure and well-being model, part I. Therapeutic Recreation Journal 41: 276–97. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, José Manuel, Alfredo Moreno, Silvia García, and Antonio Crego. 2003. Aproximación psicosocial a la motivación turística: Variables implicadas en la elección de Madrid como destino. Estudios Turísticos 158: 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, Gurel, and Fusun I. Dincer. 2014. Influence of Customer Experience on loyalty and word-of-mouth in hospitality operations. Anatolia 25: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Li-Hui. 2017. Tourists’ perception of dark tourism and its impact on their emotional experience and geopolitical knowledge: A comparative study of local and non-local tourist. Journal of Tourism Research & Hospitality 6: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Chang, Zhuoqi Teng, Chunyi Lu, Md Alamgir Hossain, and Yuantao Fang. 2021. Rethinking Leisure Tourism: From the Perspective of Tourist Touch Points and Perceived Well-being. SAGE Open 11: 21582440211059180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chun-Chu, and James F. Petrick. 2016. The roles of Perceived Travel Benefits, importance, and constraints in predicting travel behavior. Journal of Travel Research 55: 509–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chun-Chu C., James F. Petrick, and Moji Shahvali. 2016. Tourism experiences as a stress reliever: Examining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research 55: 150–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, Prem, Colin Arrowsmith, and Mervyn Jackson. 2004. Determining Hiking Experiences in Nature-based Tourist Destinations. Tourism Management 25: 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Christina Geng-Qing, and Hailin Qu. 2008. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An Integrated Approach. Tourism Management 29: 624–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, Dennis. 1990. The Essentials of Factor Analysis. London: Cassell Educational. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Wynne W. 1998. Commentary: Issues and Opinions in Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q 22: vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Youngjoon, Jihee Kim, Choong-Ki Lee, and Benjamim Hickerson. 2015. The role of functional and wellness values visitors’ evaluation of spa experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 20: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Bee-Lia L., Sanghyeop Lee, Hyeon Cheol Kim, and Heesup Han. 2017. Investigating the key drivers of traveler loyalty in airport lounge settings. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 22: 651–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark-Kennedy, James, and Marc Cohen. 2017. Indulgence or therapy? Exploring the characteristics, motivations, and experiences of hot springs bathers in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 22: 501–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Joel B., and Charles S. Areni. 1991. Affect and Consumer Behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Behavior. Edited by Thomas S. Robertson and Harold H. Kassarjian. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, pp. 188–240. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, Ed. 1984. Subjective Well-Being. Psychology Bulletin 95: 542–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillette, Alana K., Alecia C. Douglas, and Carey Andrzejewski. 2021. Dimensions of holistic wellness as a result of international wellness tourism experiences. Current Issues in Tourism 24: 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, Preslav. 2012. Long-term forecasting of the spa and wellness subsector of the Bulgarian tourism industry. Tourism Management Studies 7: 140–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, Diana. 2013. Spa and wellness tourism as spatially determined products of health resorts in Poland. Current Issues of Tourism Research 2: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dryglas, Diana, and Marcin Salamaga. 2017. Applying destination attribute segmentation health tourists: A case study of Polish spa resorts. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 34: 503–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfurt-Cooper, Patricia, and Malcom Cooper. 2009. Health and Wellness Tourism: Spas and Hot Springs. Bristol: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Faullant, Rita, Kurt Matzler, and Todd A. Mooradian. 2011. Personality, basic emotions, and satisfaction: Primary emotions in the mountaineering experience. Tourism Management 32: 1423–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, Kevin, and Alexandra Coghlan. 2016. Exploring the Positive Psychology Domains Well-being activated through charity sports event experiences. Event Management 20: 181–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, Charlotte, and Sabine Sonnentag. 2006. Recovery, Well-Being, and Performance-Related Outcomes: The Role of Workload on Vacation Experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 936–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gabor, Manuela Rozalia, and Flavia Dana Oltean. 2019. Babymoon Tourism between emotional well-being service for medical tourism and niche tourism. Development and awareness of Romanian Educated women. Tourism Management 70: 170–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvanova, Magdalena, Krasimira Staneva, and Ivan Garvanov. 2021. Wellness Tourism Approaches Improving the Quality of Life of Mobile Users. CroDiM 4: 141–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, David, and Junaida Abdullah. 2002. A study of the impact of the expectation of a holiday individual’s sense of well-being. Journal of Vacation Marketing 8: 352–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, David, and Junaida Abdullah. 2004. Holiday taking and The Sense of Well-being. Annals of Tourism Research 31: 103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, Shaked M., and Ram Herstein. 2012. Place status, place loyalty, and wellbeing: An exploratory investigation of Israel residents. Journal of Place Management and Development 5: 141–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M., N. Haghtalab, and E. Shamshiry. 2016. Wellness tourism in Saren, Iran: Resources, planning, and development. Current in Issues Tourism 19: 1071–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulimaris, Dimitris, George Mavridis, Maria Genti, and Stella Rokka. 2014. Relationships between Basic Psychological Needs And psychological well-being in recreational dance activities. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 14: 277–84. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, Ulrike, Daniel R. Fesenmaier, Sandro Formica, and Joseph T. O’Leary. 2006. Searching for the Future: Challenges Faced by Destination Marketing Organizations. Journal of Travel Research 45: 116–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GWI. 2021. The Global Wellness Tourism Economy Report. Available online: http://www.globalwellnesssummit.com/images/stories/pdf/wellness_tourism_economy_exec_sum_final_10022013.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Hair, Joseph F., Marko Sarstedt, Pieper M. Torsten, and Christian M. Ringle. 2012. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan 45: 320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2006. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed. Hoboken: Pearson-Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Michael C. 2011. Health and Medical Tourism: A kill or cure for global public health? Tourism Review 66: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Heesup, and Chul Jeong. 2013. Multi-dimensions of patrons’ emotional experiences in upscale restaurants and their role in loyalty formation: Emotion scale improvement. International Journal of Hospitality Management 32: 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Heesup, Kiattipoom Kiatkawsin, Wansoo Kim, and Sangyeop Lee. 2017. Investigating customer loyalty formation for wellness spa: Individualism Vs. Collectivism. International Journal of Hospitality Management 67: 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, Vincent, and Deniz Kucukusta. 2013. Wellness tourism in China: Resources, development and marketing. International Journal of Tourism Research 15: 346–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, Anne-Mette, and Henna Konu. 2011. Co-branding and co-creation wellness tourism: The role of cosmeceuticals. Journal of Hospitality and Marketing Management 20: 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, Sameer, and Girish Prayag. 2013. Patterns of tourists’ emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Business Research 66: 730–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, Sameer, and Mark Witham. 2010. Dimensions of Cruisers Experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research 49: 351–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, Sameer, Girish Prayag, S. Dee Latham, Siripan Cauševic, and Khaled Odeh. 2015. Measuring Tourists Emotional Experiences: Further Validation of The Destination Emotions Scale. Journal of Travel Research 54: 482–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howell, Ryan T., and Graham Hill. 2009. The mediators of experiential purchases: Determining the impact of psychological needs satisfaction and social comparison. Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 511–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, Rick H. 1995. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Songshan, and Cathy H. C. Hsu. 2009. Effects of travel motivation, past experience, perceived constraint, and attitude on revisit intention. Journal of Travel Research 48: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yu-Chih, Chun-Chu Bamboo Chen, and Mingjie Jessie Gao. 2019. Customer Experience, well-being, and loyalty in spa hotel context: Integrating the Top-down bottom-up theories well-being. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 36: 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Tak Kee, David Wan, and Alvin Ho. 2007. Tourists’ satisfaction, recommendation and revisiting Singapore. Tourism Management 28: 965–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hun, Kim Byung, and Adarsh Batra. 2009. Healthy-living behaviour status and motivational characteristics of foreign tourists to visit wellness facilities in Bangkok. Paper presented at the 2nd Annual PSU Phuket Research Conference, Songkhla, Thailand, November 18–20; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Jinsoo, and Jung Hoon Lee. 2019. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on The Experience Economy. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 36: 314–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Jinsoo, and Seong Ok Lyu. 2015. The antecedents and consequences of well-being perception: An Application of The Experience Economy to Golf Tour name tourists. Journal of Destination Marketing Management 4: 248–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, Nor Lelawati Binti, David Lackland Sam, Gro Mjeldheim Sandal, and Ainul A. Adam. 2016. Personal values, subjective well-being, and destination-loyalty intentions of international students. Springer Plus 5: 720–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Eojina, Langlung Chiang, and Liang Tang. 2017. Investigating Wellness Tourists Motivation, engagement and loyalty: In Search of The Missing link. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 34: 867–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyeon-Cheol, Bee-Lia Chua, Sanghyeop Lee, Huey-Chern Boo, and Heesup Han. 2016. Understanding Airline Travelers Perceptions Well-being: The Role of Cognition, emotion, and sensory experiences in airline lounges. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 33: 1213–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jong-Hyeong, J. R. Brent Ritchie, and Bryan P. McCormick. 2012. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research 51: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knobloch, Uli, Kirsten Robertson, and Rob Aitken. 2017. Experience, emotion, and eudaimonia: Consideration of Tourist Experiences and Well-being. Journal of Travel Research 56: 651–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, Ned, and Gary Lynn. 2012. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kong, Weng H., and Tung-Zong Chang. 2016. Souvenir Shopping, tourist motivation, and travel experience. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism 17: 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, Veera, and Terhi-Anna Wilska. 2019. Identifying and understanding spa tourists’ wellness attitudes. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 19: 259–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukusta, Denniz, Loretta Pang, and Sherry Chui. 2013. Inbound Travelers Selection Criteria for Hotel Spas in Hong Kong. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 30: 557–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, Riadh. 2009. Service quality, emotional satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: A study in the hotel industry. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal 19: 308–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, Jennifer, and Warwick Frost. 2016. Dark tourism and dark events: A journey to positive resolution and well-being. In Positive Tourism. London: Routledge, pp. 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jenny Jiyeon, and Gerard T. Kyle. 2013. The measurement of emotions elicited within festival contexts: A psychometric test of a festival consumption emotions (FCE) scale. Tourism Analysis 18: 635–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jiyeon. 2014. Visitors’ emotional responses to the festival environment. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 31: 114–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Tsung Hung. 2010. A structural model to examine how destination image, attitude, and motivation affect the future behavior of tourists. Leisure Sciences 31: 215–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, Xinran Y., Sally Brown, Yi Chen, and Alastair M. Morrison. 2006. Yoga tourism as a niche within the wellness tourism market. Tourism and Recreation Research 31: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mimi, Liping A. Cai, Xinran Y. Lehto, and Joy Z. Huang. 2010. A missing link in understanding revisits intention—The role of motivation and image. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 27: 335–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Yeqiang, Deborah Kerstetter, Jeroen Nawijn, and Ondrej Mitas. 2014. Changes in emotions and their interactions with personality in a vacation context. Tourism Management 40: 416–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, Sandra Maria Correia. 2014. The role of the rural tourism experience economy places attachment and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management 40: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, Sandra Maria Correia, Marta Almeida, and Paulo Rita. 2013. The effect of atmospheric cues and involvement on pleasure and relaxation: The spa hotel context. International Journal of Hospitality Management 35: 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Yi, Chiang Lanlung, Eojina Kim, Liang Rebecca Tang, and Sung Mi Song. 2018. Towards quality of life: The effects of the wellness tourism experience. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 35: 410–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, Rebort C. 2012. Model specification: Procedures, strategies, and Related Issues. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Edited by Rick H. Hoyle. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, Athena H., Kevin K. Wong, and Richard C. Chang. 2009. Healthorself-indulgence? The Motivations and Characteristics of Spa-goers. International Journal of Tourism Research 11: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhas, Parikshat Singh, and Singh Ramjit. 2013. Customer Experience and Its Relative Influence Satisfaction and Behavioural Intention in Hospitality and Tourism Industry. South Asian Journal of Tourism and Heritage 6: 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marmion, Maeve, and Ann Hindley. 2018. Tourism and Health: Understanding the Relationship. Good Health and Wellbeing. In Good Health and Well-Being. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Edited by Leal Walter Filho, Tony Wall, Anabela Marisa Azul, Luciana Brandli and Pinar Gokcin Özuyar. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, Scott, and Sarah Johnson. 2013. The Happiness Factor Tourism: Subjective Well-being social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 41: 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, Kimberly R., and Edna J. Ragins. 2005. Staying in the spa marketing game: Trends, challenges, strategies and techniques. Journal of Vacation Marketing 11: 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Muñoz, Diego Ramón, and Rita Dolores Medina-Muñoz. 2013. Critical Issues in Health and Wellness Tourism: An exploratory study of visitors to wellness centres on Gran Canaria. Current Issues in Tourism 16: 415–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Bo, and Kyuhwan Choi. 2017. The restaurant servicescape in developing the quality of life: The moderating effect of perceived authenticity. International Journal of Hospitality Management 65: 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milman, Ady. 1998. The impact of tourism and travel experience senior travelers’ psychological well-being. Journal of Travel Research 37: 166–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitas, Ondrej, Careen Yarnal, Reginald Adams, and N. Ram. 2012. Taking a “peak” at leisure travelers’ positive emotions. Leisure Sciences 34: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Heesup, and Hyouguen G. Han. 2018. Destination attributes influencing Chinese travelers’ perceptions of experience quality and intentions for island tourism: A case of Jeju Island. Tourism Management Perspectives 28: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Nigel, Annette Pritchard, and Diane Sedgley. 2015. Social Tourism and Wellbeing In Later Life. Annals of Tourism Research 52: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mueller, Hansruedi, and Evelin L. Kaufmann. 2001. Wellness Tourism: Market analysis of a particular health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry. Journal of Vacation Marketing 7: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naidoo, Perunjodi, and Richard Sharpley. 2016. Local perceptions of the relative contributions of enclave tourism and agritourism to community well-being: The case of Mauritius. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 5: 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nawijn, Jeroan. 2011. Determinants of Daily Happiness on Vacation. Journal of Travel Research 50: 559–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, Jeroan, Miquelle A. Marchand, Ruut Veenhoven, and Ad J. Vingerhoets. 2010. Vacationers are happier, but most are not happier after holiday. Applied Research on Quality of Life 5: 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nawijn, Jeroan, Ondrej Mitas, Yeqiang Lin, and Deborah Kerstetter. 2013. How Do We Feel on Vacation? A closer look at how emotions change over the course of a trip. Journal of Travel Research 52: 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Janet D., Joseph M. Sirgy, and Muzaffer Uysal. 1999. The role of satisfaction with leisure travel/tourism services and experience in satisfaction with leisure life and overall life. Journal of Business Research 44: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, David B., Louis Tay, and Ed Diener. 2014. Leisure and subjective well-being: A Model of Psychological Mechanisms as Mediating Actors. Journal of Happiness Studies 15: 555–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, Angelo, and Anton Grobler. 2017. Spirituality, Wellness Tourism, and quality of life. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure 6: 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. 1978. Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Haemoon, Anne Marie Fiore, and Miyoung Jeoung. 2007. Measuring Experience Economy Concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Tourism Research 46: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J. E., and B. R. Ritchie. 1996. The Service Experience in Tourism. Tourism Management 17: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Stephen J., Heather Hartwell, Nick Johns, Alan Fyall, Adele Ladkin, and Ann Hemingway. 2017. Case study: Wellness, tourism and small business development UK coastal resort public Engagement in Practice. Tourism Management 60: 466–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Xumei, Zhaoping Yang, Fang Han, Yayan Lu, and Qin Liu. 2019. Evaluating potential areas for mountain wellness tourism: A case study of Ili, Xinjiang Province. Sustainability 11: 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearce, Philippe L. 1993. Fundamental of tourist motivation. In Tourism Research: Critiques and Challenges. Edited by Douglas G. Pearce and Richard W. Butler. London: Routledge, pp. 113–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pforr, Christof, and Cornelia Locher. 2012. The German spa and health resort industry in light of healthcare system reforms. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing 29: 298–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. James, and Joseph H. Gilmore. 1999. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business Is a Stage. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, Girish, Samir Hosany, and Kalhed Odeh. 2013. The role of tourists’ emotional experiences and satisfaction in understanding behavioral intentions. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2: 118–27. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, Girish, Samir Hosany, Birgit Muskat, and Giacomo DelChiappa. 2017. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research 56: 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prebensen, Nina, Kare Skallerud, and Joseph S. Chen. 2010. Tourist motivation with sun and sand destinations: Satisfaction and the WOM-effect. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 27: 858–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke, Sarah, Heather Hartwell, Adam Blake, and Ann Hemingway. 2016. Exploring Well-being as a tourism product resource. Tourism Management 55: 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quadri-Felitti, Donna L., and Anne Marie Fiore. 2013. Destination loyalty: Effects of Wine Tourists Experiences, memories, and satisfaction intentions. Tourism of Hospitality Research 13: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, Prabha, Vishwadeo N. Seebaluck, and Perunjodi Naidoo. 2015. Examining the Structural Relationships of Destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Case of Mauritius. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Science 175: 252–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rigdon, E. E. 1998. Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Method for Business Research, Marcoulides. Edited by G. A. Marcoulides. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 251–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, Áurea, Elisabeth Kastenholz, and Apolónia Rodrigues. 2010. Hiking as a relevant wellness activity-results of nexploratorystudyofhiking tourist in Portugal applied areal tourism project. Journal of Vacation Marketing 16: 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Ariel, Pavlína Látková, and Ya-Yen Sun. 2008. The relationship between leisure and life satisfaction: Application of activity and need theory. Social Indicators Research 86: 163–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Pramod, and Jogendra K. Nayak. 2018. Testing the role of tourists’ emotional experiences in predicting destination image, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: A wellness tourism case. Tourism Management Perspectives 28: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, Edgardo, Roberta Sisto, Piervito Bianchi, and Giulio Cappelletti. 2021. Inclusivity and Responsible Tourism: Designing a Trademark for a National Park Area. Sustainability 13: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. Joseph. 2010. Toward a quality-of-life theory of leisure travel satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research 49: 246–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Melamie, and Catherine Kelly. 2006. Wellness tourism. Tourism Recreation Research 31: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Melanie, and László Puczkó. 2008. Health and Wellness Tourism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Melanie, and László Puczkó. 2014. Health, Tourism, and Hospitality: Spas, Wellness, and Medical Travel. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Melanie K., and Anya Diekmann. 2017. Tourism and Wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research 66: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivack, Sheryl Elliot. 1998. Health Spa Development in the US: A burgeoning Component of Sport Tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing 4: 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss-Blasche, Gerhard W., Cem Ekmekcioglu, and Wolfgang Marktl. 2002. Moderating Effects of Vacation Reactions Work and Domestic stress. Leisure Science 24: 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, Dwi, Anthony Brien, Ina Primiana, Nono Wibisono, and Ni Nyoman Triyuni. 2020. Tourist Loyalty in Creative Tourism: The Role of Experience Quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Current Issues in Tourism 23: 867–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, Karen Irene, and Simon Hudson. 2017. A conceptual model of wellness destination characteristics that contribute to psychological well-being. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 43: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, Muzaffer, M. Josef, Eunju Woo, Eunju, and Hye Lin Kim. 2016. Quality of Life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management 53: 244–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, Sera, Catherine Prentice, and Aaron Hsiao. 2019. The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. Journal of Retail and Consumer Service 47: 322–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, Cornelia. 2016. Employing hedonia and eudaimonia to explore differences between three wellness tourists at the experiential, motivational, and global levels. In Positive Tourism. Edited by Filep Sebastian, Laing Jennifer and Csikszentmihalyi Mihaly. London: Routledge, pp. 119–35. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, Cornelia, Graham Brown, and Gary Howat. 2011. Wellness Tourists: In search of transformation. Tourism Review 66: 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ke, Ganghong Xu, and Liyuan Huang. 2020. Wellness tourism and spatial stigma: A Case Study of Bama, China. Tourism Management 78: 104039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, Stephen L., and Carmel Foley. 2017. Understanding the tourist experience of cities. Annals of Tourism Research 65: 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, Kara, and Cathy H. C. Hsu. 2004. An application of the social psychological model of tourism motivation. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 5: 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, Robert B., Ernest R. Cadotte, and Roger L. Jenkins. 1983. Modeling consumer satisfaction processes using experience-based norms. Journal of Marketing Research 20: 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Bing Jin, Jie Zhang, Hong Lei Zhang, Shao Jing Lu, and Yong Rui Guo. 2016. Investigating the motivation experience relationship on dark tourism space: A case study of the Beichuan Earthquake relics, China. Tourism Management 53: 108–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Yooshik, and Muzaffer Uysal. 2005. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tourism Management 26: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, Attila. 2007. Tourist shopping habitat: Effects on emotions, shopping value, and behaviors. Tourism Management 28: 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, Attila, and Fisun Yüksel. 2007. Shopping Risk Perceptions: Effects Tourists Emotions, satisfaction and expressed loyalty intentions. Tourism Management 28: 703–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Fang, Qin Su, Yun Tao, and Jinghong Shen. 2020. Environmental Restorative Effects of Destination for Tourists from the Perspective of Tourist-Environment Interaction. Tropical Geography 40: 636–48. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | No. of Items | Cronbach Alpha (α) Value |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 04 | 0.903 |

| Intrinsic Motivation | 05 | 0.825 |

| Experience | 05 | 0.828 |

| Positive Emotions | 06 | 0.894 |

| Life Satisfaction | 05 | 0.849 |

| Loyalty | 03 | 0.871 |

| Characteristics | Number (n) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (138) | 52.27% |

| Female (126) | 47.73% | |

| Age | 18–30 years (97) | 36.75% |

| 31–43 years (84) | 31.82% | |

| 44–55 years (63) | 23.86% | |

| 56 Above (20) | 7.57% | |

| Education | Elementary school (11) | 4.16% |

| Middle school (19) | 7.20% | |

| High school (31) | 11.75% | |

| Bachelor’s degree (126) | 47.72% | |

| Master’s degree (70) | 26.51% | |

| Higher (7) | 2.65% | |

| Occupation | Employee (183) | 69.31% |

| Unemployed (43) | 16.28% | |

| Student (32) | 12.12% | |

| Retired (6) | 2.27% | |

| Annual Income | Less than 50,000 Rs (05) | 1.89% |

| 50,000 to 100,000 Rs (11) | 4.16% | |

| 100,000 to 150,000 Rs (17) | 6.44% | |

| 150,000 to 200,000 Rs (83) | 31.43% | |

| Above 200,000 Rs (148) | 56.06% |

| Dimensions | Items | Loadings | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy (AUT) | 0.774 | 0.932 | ||

| When taking the vacation, I experienced a lot of freedom | (AUT1) | 0.821 | ||

| While taking the vacation, I did things because they interested me | (AUT2) | 0.891 | ||

| Taking vacation provides me with interesting options and choices | (AUT3) | 0.910 | ||

| I did not feel pressured to be a certain way when taking a vacation | (AUT4) | 0.895 | ||

| Intrinsic Motivation (IntrMot) | 0.620 | 0.884 | ||

| To gain a sense of renewal | (IntrMot1) | 0.886 | ||

| To enjoy an experience with all my senses | (IntrMot2) | 0.890 | ||

| To improve my health | (IntrMot3) | 0.788 | ||

| To improve my appearance | (IntrMot4) | 0.878 | ||

| To share my experiences with people, I am close to | (IntrMot5) | 0.361 | ||

| Experience (EXP) | 0.621 | 0.886 | ||

| I have beautiful memories of my spa visit | (EXP1) | 0.878 | ||

| I remember many positive things about my last spa visit | (EXP2) | 0.879 | ||

| I completely escaped from reality | (EXP3) | 0.785 | ||

| The setting pleasured my senses | (EXP4) | 0.872 | ||

| The experience has made me more knowledgeable | (EXP5) | 0.430 | ||

| Positive Emotions (PostEmo) | 0.654 | 0.918 | ||

| Cheerful | (PostEmo1) | 0.811 | ||

| Relaxing | (PostEmo2) | 0.862 | ||

| Inspired | (PostEmo3) | 0.885 | ||

| Active | (PostEmo4) | 0.874 | ||

| Excited | (PostEmo5) | 0.713 | ||

| Interested | (PostEmo6) | 0.686 | ||

| Life Satisfaction (LS) | 0.618 | 0.889 | ||

| In most ways, my life was close to my ideal | (LS1) | 0.794 | ||

| The conditions of my life were excellent | (LS2) | 0.789 | ||

| I was satisfied with my life | (LS3) | 0.850 | ||

| I felt I had the essential things I wanted in life | (LS4) | 0.818 | ||

| If I could have lived my life over, I would change almost nothing | (LS5) | 0.667 | ||

| Loyalty (LOY) | 0.789 | 0.918 | ||

| Willingness to recommended | (LOY1) | 0.827 | ||

| Saying positive things to other people | (LOY2) | 0.928 | ||

| Willingness to return to the travel destination in the future” | (LOY3) | 0.906 |

| AVE | AUT | EXP | INMOT | LS | LOY | POEMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUT | 0.774 | 0.880 | |||||

| EXP | 0.383 | 0.342 | 0.788 | ||||

| INMOT | 0.352 | 0.566 | 0.379 | 0.787 | |||

| LS | 0.555 | 0.472 | 0.447 | 0.411 | 0.786 | ||

| LOY | 0.259 | 0.272 | 0.261 | 0.356 | 0.182 | 0.888 | |

| POEMO | 0.976 | 0.430 | 0.39 | 0.361 | 0.602 | 0.272 | 0.809 |

| Path Coefficients | T Statistics | p Values | Inference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic motivation → Experience | 0.983 | 138.31 | 0.005 | Supported |

| Autonomy → Experience | 0.037 | 2.60 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Autonomy → Positive Emotions | 0.951 | 60.35 | 0.011 | Supported |

| Autonomy → Life Satisfaction | 0.439 | 4.61 | 0.049 | Supported |

| Experience → Loyalty | 0.200 | 2.06 | 0.089 | Supported |

| Experience → Positive Emotions | 0.066 | 2.16 | 0.007 | Supported |

| Experience → Life Satisfaction | 0.304 | 3.01 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Positive Emotions → Loyalty | 0.209 | 2.18 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Life Satisfaction → Loyalty | 0.308 | 3.76 | 0.000 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, R.; Manhas, P.S.; Mir, M.A.; Quintela, J.A. Investigating the Relationship between Experience, Well-Being, and Loyalty: A Study of Wellness Tourists. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030098

Singh R, Manhas PS, Mir MA, Quintela JA. Investigating the Relationship between Experience, Well-Being, and Loyalty: A Study of Wellness Tourists. Administrative Sciences. 2022; 12(3):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Ramjit, Parikshat Singh Manhas, Mudasir Ahmad Mir, and Joana A. Quintela. 2022. "Investigating the Relationship between Experience, Well-Being, and Loyalty: A Study of Wellness Tourists" Administrative Sciences 12, no. 3: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12030098