1. Introduction

In today’s global marketplace, franchising is a method of operating and growing a firm. A franchise is a license that enables a franchisee to use the franchisor’s brand name to sell goods and services by accessing the franchisor’s secret business techniques, procedures, and branding (

Boulay and Stan 2013). The franchisee typically pays the franchisor an initial start-up cost and yearly licensing fees in exchange for obtaining a franchise. The agreement involving franchisors and franchisees outlines how they will divide the earnings from the franchising business (

Lee et al. 2021). Since a franchisor has already refined everyday operations via experimenting, new franchisees can avoid many of the pitfalls that start-up businesses frequently make. The franchisor also shows franchisees exactly who their competitors are and how they can set themselves apart. Moreover, when purchasing goods, services, conducting advertising campaigns, and negotiating locations and leasing terms, the franchisees will benefit from economies of scale.

Due to its role as a significant employer and driver of growth, franchising is crucial to modern business (

Khan 2013). It is critical to comprehend the position that franchising plays in the economy as it is a significant source of jobs and economic output. Thousands of options for small business owners and millions of employment prospects have been made possible through the franchise sector. Moreover, it is an effective and practical method to expand the firm with a cost-effective budget on a currently successful firm through franchising (

Madanoglu et al. 2018). It facilitates a company’s rapid growth and increases the variety of markets quickly and affordably. The franchisors will have fewer management responsibilities as the franchisees also run their businesses. The finest franchisees will be highly driven and knowledgeable about their territorial area, making the franchisor’s life much more straightforward.

Whilst growth commenced in 1992, when the government began promoting the industry, franchising in Malaysia is still in its early development stage. At the time of the introduction of franchise business in Malaysia, few franchise businesses were operated in Malaysia, such as Singer, Bata, Petrol Stations, and car authorized dealers. However, Malaysia has consistently adopted pro-franchise policies and welcomes franchisors worldwide to conduct the business. This is consistent in making Malaysia the ASEAN franchise hub. Moreover, based on consistent and robust development, the franchise sector in Malaysia is on target to reach its contribution of RM11.8 billion to the national gross domestic product (GDP) in 2021 (

Ministry of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs 2021).

Critical success factors (CSFs) are particular components or action areas that a firm, team, or department must concentrate on and effectively implement to achieve its strategic goals (

Bullen and Rockart 1981;

Sanchez Badini et al. 2018). Critical success factors are a few areas where achieving satisfactory outcomes will guarantee that an individual, department, or organization performs successfully in a competitive environment where “things must go right” for the business to succeed and for the firm’s objectives to be met (

Bullen and Rockart 1981). A data collection, analysis, and discussion are typically used to identify critical success factors. They help an organization move closer to its strategic goals by determining how a business unit, department, or function may accomplish its particular aims.

Building a great brand may be valuable, and businesses should go on this trip if they want to succeed. Critical success factor-related activities must be carried out to the highest standard of excellence to accomplish the intended overall objectives. However, since the existing literature on the critical success factors in the franchising sector in developing countries such as Malaysia is still scarce, this study is expected to answer the following research question: what are the critical success factors of franchising firms from the franchisor and franchisee perspective? Therefore, to fill the research gap, there is a need to determine the critical success factors within the franchising area.

2. Literature Review

Critical success factors are the best practices, keys, or enablers that help organizations perform well (

Ali and Johl 2022;

Hietschold et al. 2014). A positive outcome and significant value creation for the business should result from effectively using these success elements. In addition, critical success factors aid decision-makers in concentrating on crucial processes that can define and lead the management’s course of action to maximize the effectiveness of decision-making processes (

de Resende et al. 2018;

Dasanayaka 2012). When they are made clear to everyone in the firm, they serve as a solid benchmark for measuring success and keeping one’s attention on the right things. Delivering the relevant and targeted critical success factors is closely related to achieving strategic goals, which requires commitment and focus.

According to Rockart (

Bullen and Rockart 1981), there are five different types of critical success factors that come from four different sources: industry CSFs, which come from the unique features of the industry; strategy CSFs, which are a result of the company’s chosen competitive strategy; environmental CSFs, which are brought on by changes in the economy or technology; and temporal CSFs, which are brought on by requirements and changes within the organization. Effective firms track their metrics over time and work to correlate them with their critical success factors (

Selimović et al. 2020). Critical success elements include the abilities, information, and assets that enable a business that has a competitive advantage (

Selimović et al. 2020). As a result, critical success factors are created through a continuing, iterative process that necessitates periodic modifications depending on experience.

The partnership’s success or failure depends heavily on the connection between the franchisor and the franchisee (

Khan 2013). The entire concept of franchising revolves around providing a contract for a set amount of time. To preserve and grow the long-term relationship of the business, there must be an emotional connection between the franchisor and the franchisee. There must be a win-win situation for both sides. Therefore, the franchisee and franchisor work together as a group. However, like every successful cooperation, some problems need to be fixed. Franchisors and franchisees can achieve and maintain the critical alignment required to keep the business growing with more outstanding communication, a focus on the future, and an agreement on the positioning of their business.

The expansion and the rational arrangement of sharing benefits and expenses are frequently necessary to develop and strengthen the partnership (

Kaufmann and Lafontaine 1994;

Michael 1999). In addition, the franchisor and franchisee must determine how to leverage technical, financial, marketing, and internet assistance in their cooperation (

Khan 2013). Franchise businesses are undoubtedly profitable, but they also depend significantly on the quality of the brand and the way they are managed. Issues between franchisors and franchisees are sparked by all of these problems, which may prevent success. For this reason, handling these issues properly and head-on is crucial to maintain a strong working relationship for many years.

To ensure constant contact and a mutual understanding, franchise partners must be highly active (

Chiou et al. 2004;

Fernández-Monroy et al. 2018). So, for franchisors to maintain effective partnerships, communication is crucial. In this regard, the quality and flow of communication are the two aspects of communication behavior that the study by (

Fernández-Monroy et al. 2018) focused on. Communication inside the system positively impacts the franchisee’s trust in a franchise system (

Chiou et al. 2004). Additionally, it was believed that the market expertise that franchisees contributed to the system would be advantageous and allow for the network-wide sharing of best practices (

Watson and Johnson 2010). On the other hand, the longevity of the franchise partners’ performances is correlated with the quality of relationships (

Varotto and Parente 2016). It takes time to develop and consolidate, and factors like trust, dedication, and relationships are involved.

2.1. Agency Theory

The best way to set up a relationship is where one party (the principal) decides what work the other party (the agent) does. For example, the principal is a franchisor, and the agent is the franchisee. This theory assists in putting into practice the numerous governance systems to manage the agents’ behavior in jointly owned enterprises (

Panda and Leepsa 2017). There are at least two methods for coordination: in the market, the price system suggests the most efficient allocation of resources, and in the firm, the authority (entrepreneur) is in charge of resource reallocation under the hierarchy principle (

Varotto and Aureliano-Silva 2017).

From the franchisor’s perspective, measuring a franchisee’s performance is one of the essential elements for success (

Chien 2014). The company must ensure that every franchisee and firm in the system puts forth the necessary effort to build and preserve the system’s brand name and image and does not try to “free ride” off the labor of those franchisees and firms. A fundamental requirement of a businesses’ survival is their ability to efficiently produce the products that customers demand at the lowest possible cost. According to the agency theory’s principles, efficiency is correlated with managing agency issues (

Varotto and Aureliano-Silva 2017). Although franchising can replace the requirement for supervision, there may be expenses to the franchisors involved.

It follows that the franchisees use the franchisor’s resources and take decisions with the principal alone, bearing the associated risks. Finally, the agency theory discusses establishing agency relationships to minimize the likelihood of disputes and other problems arising between franchisors and franchisees. Franchisees become more confident and willing to assume a measured degree of risk with the franchisor as their relationship develops in commitment and trust (

Shaikh et al. 2018). Therefore, strengthening the franchisor’s control through higher levels of centralization is more beneficial in already established systems (

López-Bayón and López-Fernández 2016).

Moreover, the leadership comes from the franchisor to craft the branding with franchisees. The study by

Klopotan et al. (

2018) demonstrates the connection between the effective use of motivating strategies, the standard of leadership styles, and employee satisfaction. Even with good firms’ innovations and support, it reverts to the decision-making and capabilities of the entrepreneur (

Macpherson and Holt 2007). Motivation from leaders would be the best method for inspiring employees, which would lead to a stronger team and firm. Leaders can interact, contribute, engage, support tasks, offer moral support and rewards, influence, cooperate, and compel employees to improve (

Hussain et al. 2018;

Joseph and Wilson 2018).

2.2. Resource Scarcity Theory

In a seminal work that started the conversation on why businesses franchise,

Oxenfeldt and Kelly (

1969) claimed that a business prefers a franchise to gain access to resources in a short supply. They stated that businesses prefer company ownership because they may anticipate greater returns from businesses held by the firm (

Combs and Ketchen 2003). Conflict over the ownership of a limited product is implied by the term “scarcity”. Franchising would benefit a franchisor mainly during the early years when basic resources such as financial capital, suitable locations, the labor supply, and managers to apply the system would be required to adopt and develop the business concept and create economies of scale (

Varotto and Aureliano-Silva 2017).

As a result, according to the resource scarcity theory, businesses turn to franchises when the need to attain economies of scale forces them to grow faster than is feasible with internally generated resources alone (

Castrogiovanni et al. 2006). According to this theory, firms offer franchises in their early years because they lack the managerial knowledge and finance required to grow, and franchisees can provide these. Younger and smaller businesses should expand their franchises, but based on their existing franchises, they should have a smaller share of franchises, given the number of stores and operational experience (

Madanoglu et al. 2018). The franchise model offers leveraged growth and entrepreneurial freedom in uncertain cash flow for the company. The franchise theory suggests firm- and location-specific variables that clarify when and why some businesses adopted franchises while others did not.

Perdreau et al. (

2015) found that human capital intangibles impact the governance structure of franchise networks (

Perdreau et al. 2015). For example, franchise owners with more experience can take advantage of their franchisees’ assets and expertise and maximize economies of scale. In addition, franchisors can decrease franchisees’ opportunistic actions through detailed operational monitoring procedures, which may be ingrained in corporate culture and lower monitoring expenses (

Sun and Lee 2018). There is an impact of the installation expenses for a new unit on the contractual mix, keeping in mind how difficult it is to obtain resources, which is crucial for the chain’s performance. Opening a new location entails spending money and taking risks, and that unit’s management skills and local expertise greatly influence the venture’s success (

Cliquet and Pénard 2012).

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Study Design

A focus a group approach was used to discover the traits of franchisors and franchisees that can contribute to the franchise system’s success in Malaysia by inviting franchisees who are already operating their businesses. With this approach, the researcher can converse with and observe the participants as they engage with one another, covering the numerous issues that have come up throughout the conversation and using them as the basis for more analysis (

Klopotan et al. 2018;

Macpherson and Holt 2007). Focus group research is most successful when the results can be used to further the objectives they were initially commissioned to reach. Therefore, it is considered a significant addition to this article’s production to discuss the best franchisor and franchisee traits that affect a franchise business’ performance.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

A focus group discussion was conducted on August 2022 to gather information from the industry players, franchisors, and franchisees to gather the findings. Three industries of seven participants gathered for the focus group discussion. The focus group discussion’s attendees are as in

Table 1.

Focus group discussions are widely employed as a qualitative strategy to comprehend social topics comprehensively. Focus group discussions are a type of data collection used in qualitative research that focuses on participants’ perspectives and experiences which are being discussed and exchanged. However, instead of using a statistically representative sample of a larger population, the process seeks to collect data from a chosen group. Furthermore, because focus group discussions are structured and directed but also expressive, they can produce a lot of information in a short period (

Muijeen et al. 2020).

The interview protocols were prepared by the researcher using semi-structured parameters. A few pre-determined questions are asked during a semi-structured discussion, while the remaining questions are unplanned in light of the study’s research issue.

Table 2 displays several illustrations of research question examples.

3.3. Data Analysis

The data acquired for the study were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. However, it is better understood as an all-encompassing phrase that designates a variety of sometimes quite distinct methods used to find commonalities or “themes” among qualitative approaches (

Braun et al. 2019). For example, a theme in a “domain summary” conceptualization summarizes what participants say in connection to a topic or issue, typically at the semantic or surface level of meaning and typically reports various or even contradicting meaning content.

Thematic analysis has been applied in six stages to identify topics in qualitative research literature related to research issues (

Shukla et al. 2019), as in

Table 3. First, the literature on measuring certain flexibilities is classified as the performance since it uses the augmentation of independent variables. The managerial paradox serves as a guide for defining the criteria for selecting the relevant articles. Second, the researcher must generate codes based on reading and article reviews. It follows by searching the themes and reviewing themes. Next, themes are titled and categorized and report production.

These six topic phases were followed in the data analysis. First, the researchers carefully read through the interview transcripts word by word to evaluate the data. Themes were then extracted from the transcript and organized into larger groupings with more specific subgroups depending on the equation by the researchers. The next step was to evaluate and interpret each topic in light of the study’s context. Finally, all researchers agreed on selecting the themes and subthemes, which were subsequently supported by the pertinent literature and provided to respondents for data validation.

Consequently, a focus group’s size can vary depending on the study’s goal, can be flexible, and should be sizable enough to allow for a group discussion (

Muijeen et al. 2020). When no new codes are found and the results start to resemble one another, data saturation occurs during the data collection and analysis (

Braun and Clarke 2021). Analyzing the determining themes and subthemes by the group and day of study gave the focus group research design a collective voice linked with it, validating the data saturation (

Hancock et al. 2016). The data saturation in this study appears in the seventh participant. Saturation is reached when researchers cannot offer more theoretically based explanations or interpretations of the data (

Faulkner and Trotter 2017).

4. Findings

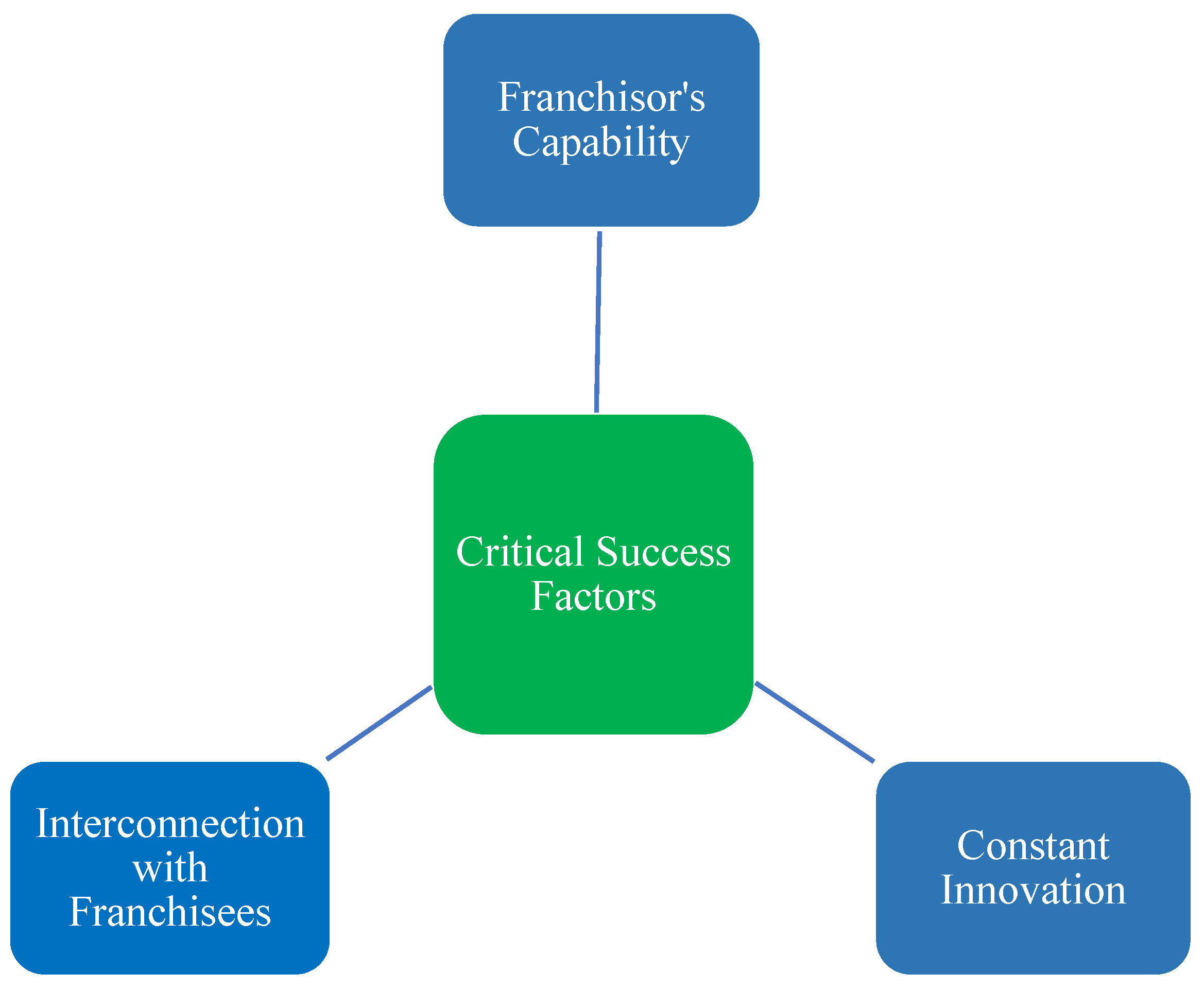

Based on the interview sessions with franchisors, franchisees, and franchising professionals, there is evidence of several important elements of critical success factors in their franchising businesses. It can be divided into three categories: the franchisor’s capability, interconnection with franchisees, and constant innovation.

4.1. Franchisor’s Capability

A franchisor with a great success is committed to its brand. It takes a lot of effort and success-driven incentives to own a franchise. Therefore, franchise ownership demands a lot of drive and success-oriented motivation. In addition, franchisees and customers investing in the goods and services need to feel inspired by the franchisor. It will trickle down to the staff and beyond if the franchisor is energetic, passionate, and sincerely believes in the principles and goals of the firm. As mentioned by Homegrown Franchisor 1, the franchisor, as a leader, needs to foster a pleasant workplace culture and appreciate each employee’s contributions to the company.

“so that’s why after five years, they have to revise everything… new blood… new CEO… new people… you know, break and re-build… because if you don’t break… the second element… you have to respond to current and in-trend environmental… demands… what do they want… sometimes we do it without proper study of the trends”

[Homegrown Franchisor 1]

Additionally, the participant highlighted a need to revise every five years to keep up with the trends and changes within the industry. The person in charge of the company must also be able to motivate the team by setting an example and drawing on personal experience rather than standing in an ivory tower issuing commands. A good franchisor recognizes the need for the company, its name, and its goods or services to change and works to improve and adapt the enterprise to retain its success. It has been highlighted by Homegrown Franchisor 3 that a clear and practical decision is crucial to sustaining the business.

“I think a lot of elements are required to sustain the business. For example, we have to have a clear goal… and also, we have a clear target to achieve… where we have to have a smart management strategy… but the most crucial thing… I think to have a practical decision, especially in managing the resources… we have to know our cost apparent and expected revenue and bring the thing at the right timing”

[Homegrown Franchisor 3]

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided the franchisor and franchisee with experience in aligning strategies and challenging environments. According to the firm business experience, a well-established crisis response capability is necessary to guarantee the effective management of incidents to minimize the associated negative effects, meet government priorities regarding maintenance and confidence, and ensure the ongoing delivery of vital national infrastructure.

“Actually… during COVID-19… on-off… we operate our outlets… but what can I say for continuity… for our survival… we have to do something… typically as I mentioned… whatever happens, we, as a franchisor… have to find a way to survive”

[Homegrown Franchisor 4]

COVID-19 appears to have changed the psychology of shopping, according to early reports. Smartphone shopping is becoming more convenient and quicker, but COVID-19 has expedited the trend. As a result, customers are placing greater expectations on firms to modify their business strategies and product portfolios to show that they are committed to sustainability. More than public relations and greenwashing are needed for this. However, continued market research on the post-COVID-19 climate will be necessary to track consumer opinion and respond to evolving buying trends to find solutions.

4.2. Interconnection with Franchisees

When it comes to franchising and how the roles of franchisor and franchisee interact, as an industry, there are times when we need to go back to the basics. Without a clear understanding, a potential franchisee can mistakenly believe that the franchisor is their “boss”, although this is in no way the case. The success of a franchise depends equally on both partners. It has been highlighted by Homegrown Franchisor 1 as sharing knowledge and inputs to grow the brand together.

“A good relationship with the franchisee is meaningful… regular franchise meetings/monthly meetings and compulsory… sharing from franchisee and franchisor to improve the franchise business… get the feedback from franchisee”

[Homegrown Franchisor 1]

Having said that, how does the franchisor care for its franchise partners? After all, a franchisor’s income objectives rely on the franchisee’s success, and the relationship between the two is crucial to comprehend, particularly in the current market. As mentioned by the participant, all elements need to be clarified. Franchisees and franchisors will share what they’ve learned about the franchisor–franchisee relationship, including how to successfully onboard and train partners and know when a particular market is ready for growth.

“Relationships between franchisor and franchisee… the brand should have a sense of belonging. The franchisor and franchisee’s role needs to be clarified in the beginning… it has to be precise. Each party has to know their role and responsibility”.

[Franchisee 1]

As a franchisee, there is a success road map to follow and a high amount of assistance built into the business. In the long term, time will be saved by recognizing the value of franchisee and franchisor relationships since they will clearly define the expectations of their roles and how they work together to manage a successful business unit.

“Therefore my experience… if I were comparing this brand and others… In terms of the system… the details of planning… to face the situation… and they are good at assisting franchisees. For me, the assistance is critical… the support… from them basically”

[Franchisee 2]

“The first thing, communication with the franchisee, is crucial… communication with franchisees. Our communication is every day… in the morning between 9.00 am to 10.00 am… all the managers, regardless of outlets… franchisor and franchisee, we have to sit down, and we share good elements that we did yesterday… good planning… so everyone manages to get the curve and guideline on what should be done… for example, during the first and second MCO… in daily routine… we did a discussion… three elements that we should do… or five elements that we should do… that within our control and we could manage to do”

[Homegrown Franchisor 4]

Only if there is open and regular communication between a franchisee and a franchisor will their business model be successful. Based on the franchisor and franchisee, the best franchises show how crucial it is to produce accurate reporting. This provides the franchisor with the data they need to make improvements to support struggling franchises. The finest franchise relationship management occurs when team members communicate honestly and frequently, assessing business unit-level deficiencies and how corporate-level brand decisions influence particular companies.

4.3. Constant Innovation

Being adaptable will ultimately increase the likelihood of surviving competition. However, innovations risk becoming obsolete if they are not constantly updated. Therefore, a corporation must concentrate on ongoing innovation to thrive and remain relevant. One of the participants highlighted that constant innovation is crucial to be aligned with technology and surrounding changes. A successful and long-lasting company designed for the post-COVID-19 era must focus on how to prosper in the face of ongoing changes, shifting consumer needs, and dynamic competitive environments. The difference will remain constant in businesses for the foreseeable future, and that much is almost guaranteed.

“Technology is crucial for the business to survive… continuity of research and development on products and services to ensure added value and benefits. Moreover, constant innovation would ensure brand continuity”

[Franchisee 2]

“We have a similar product: a bring-your-own-device (BYOD) for doing their order using their phone. This device is called artificial intelligence (AI). If you go to our brand one day and order your food using your log-in, later on… the next visit, when you log in to the same platform… they will be able to suggest you… what you like… based on your oracle data. So, it’s the changes in terms of digitalising business, and you depend less on your workers… the labours”

[Homegrown Franchisor 3]

Although technological advancements are transforming the business world, technology cannot stand alone as a differentiation. Every business model component must continuously innovate to survive, expand, and stand out from competitors. Knowing what and whose problem you are fixing will help you determine what value your company offers that client.

“The only thing we have to adapt and align is together with the international level… and not only make a comparison in Malaysia… so you have to react internationally… so it is our progress… we had one outlet that specifically a model for international… fully electrical equipment as our innovation”

[Homegrown Franchisor 4]

The company’s long-term success is guaranteed by continuous innovation, while a great routine ensures its short-term success. Innovation is organic during routine mechanistic behavior.

5. Discussion

Based on the thematic analysis developed from the interviews with the participants, three critical success factors of franchisor and franchisee appeared: the franchisor’s capability, interconnection with franchisees, and constant innovation.

5.1. Franchisor’s Capability

The personal background provides general knowledge about a person. As a principle of a personal background, two characteristics are involved: attribute and attained (

Sarwoko et al. 2013). The attributes are a factor that is an entrepreneur in itself, which includes gender and age. Personal attributes are critical for an outstanding team (

Nancarrow et al. 2013), while attained attributes are based on the education and experience of the entrepreneurs. Therefore, both types complement each other in their background. Instead of conventional wisdom, progressive thought offers new perspectives on how things should be done. Thinking quickly and analytically is essential for taking action and surviving. Moreover, the idea and thought must be original to adjust to the current environment.

It serves as the company’s primary brand identity and the image that customers have in mind when hearing about the brand. Therefore, to effectively shape the organization, the franchisor must devote time and effort to developing a brand strategy. Precise and proper planning must be explained through franchisees to deliver the same messages as a brand. As a business owner, a franchisor spends a lot of time and energy deciding whether to act unilaterally; yet once he has decided to take the initiative, he must do it before anyone else. A successful entrepreneur possesses the qualities of a creative thinker and an innovator. To thrive, business owners, either franchisors or franchisees, need to hold the majority of entrepreneur competencies.

Creativity aims to create new goods and services that address unmet consumer needs; the most practical ideas complement the organization’s business model. The franchisor can narrow the field of opportunity so that only the most worthwhile ideas get the team’s attention by identifying and refining the early concepts and then measuring those concepts against defined success metrics. This is true whether the franchisor is looking to commercialize new technologies, expand physical product portfolios, develop digital tools to expand the brand value proposition, or launch new adjacent service offerings. Strategic adaptability is responding quickly when environmental and corporate conditions change unexpectedly. When things go as planned, many businesses plan their operations well. Long-term viability is frequently correlated with flexible planning by firms. Over the course of a year, the client’s expectations and the available technology often change. Strategic flexibility creates a response in terms of marketing research, development, and promotion to a shifting market.

The Big Five is commonly used by psychologists and established as a comprehensive predictor of human personality (

Clifton Green et al. 2019;

Zhou and de Wit 2011), extraversion, agreeableness, emotional stability, openness to experience, and conscientiousness (

Judge et al. 1999;

John et al. 2008). Extraversion is characterized as outgoing and active (

Clifton Green et al. 2019), leading to assertive, aggressive, enthusiastic, outgoing, vocal, dominant, forceful, enthusiastic, show-off, friendly, spunky, adventurous, loud, and bossy (

John et al. 2008). Agreeableness expresses itself in human behavioral traits that are viewed as kind, compassionate, cooperative, warm, and thoughtful (

DeYoung 2015;

Thompson 2008). Next, emotional stability refers to an individual’s capacity to stay stable and strong (

Zhang and Schutte 2015), where the more stable the emotion, the better the performance will be (

Alessandri and Vecchione 2012;

Zhang and Schutte 2015). Finally, an openness to experience describes human variations in cognitive exploration, the tendency to search, detect, capture, and learn, and the ability to use both sensory and abstract knowledge (

DeYoung 2015). In contrast, conscientiousness is a propensity to show self-discipline, to behave dutifully, and to aim for success way more than expectations (

O’Reilly et al. 2014).

These personality traits play a part in the psychological of an individual that would affect the firm’s growth. Clifton Green et al. (

Clifton Green et al. 2019) found convincing evidence that corporate extraversion is linked with a better productivity and performance. One of the major factors shaping the business landscape is personnel capability (

Gupta et al. 2013). A strong personality would support the achievement of a firm in the long term.

Zhou and de Wit (

2011) claimed that there could be a strong relationship between the desire for accomplishment and a firm’s growth. The value of the relationship between a franchisor and a franchisee is crucially understood by a great franchisor, who recognizes that a network of franchisees is not simply a means of brand expansion but also a resource of talent and expertise should be recognized and valued.

Excellent franchisors are strong leaders with the capacity to inspire others. However, the franchisor may struggle to scale his organization if they discover that they are currently handling most of its operations. The franchisor should be able to mentor franchisees and have faith in their ability to perform at a high level with the franchisor’s help. As soon as the network is established and you have franchisees to assist and train, franchising is a marketing and sales business. The entrepreneur must be prepared to motivate employees and persuade new potential investors of the business’s mission. The best franchisors are willing to sell and genuinely enjoy doing it.

Specifically, this finding proposed a proposition:

Proposition 1. The existence of a franchisor’s capability is positively associated with the critical success factors of a franchising business.

5.2. Interconnection with Franchisees

A good franchisor–franchisee relationship is like the business equivalent of a marriage. It is interdependent and calls for the cooperation of both sides, which means that if it is going to work, good communication skills and business judgement are required. The basis for success will be a solid corporate identity and consistent business strategies, while competent leadership and effective communication guarantee that all sides are involved. For franchisors to sustain beneficial partnerships, communication is a crucial element (

Fernández-Monroy et al. 2018). A healthy and fruitful connection will simplify success if the franchisor and the franchisee both endeavor to accomplish these criteria. In addition, a good relationship with franchisees involves regular meetings, idea sharing, and feedback assistance.

According to earlier franchising studies, communication enables people to create trust (

Faulkner and Trotter 2017;

Sarwoko et al. 2013). However, franchise owners can suffer significantly from a lack of communication, especially concerning finances. In addition, without clear communication or an input from the franchisors themselves, changes made at the corporate level can trickle down to franchisees. Therefore, a franchisor’s responsibility is to create avenues of communication with the franchisees that are both formal and informal. Regular meetings, visiting franchisees’ locations, and being receptive to their feedback are a few of the finest strategies for building strong communication. As for the franchisee, take the initiative to contact the franchisor. Utilize meetings and face-to-face time to raise issues, express worries, and offer advice on how the franchisor and franchisees as partners may achieve their goals.

Although most franchisees base their franchise evaluation on its business model and brand, the franchisor can provide an additional value to franchisees. By lowering incentives for free-riding on the part of both the franchisor and the franchisee, a franchisor’s techniques for structuring and managing exchange relationships with current franchisees can alleviate the moral hazard problem (

Kacker et al. 2016). The franchisor should assist its franchisees in maximizing revenue while ensuring that the end-customer needs are still met. This will help franchisees keep their operational costs as low as is feasible. By using economies of scale to buy supplies, goods, or raw materials, performing centralized marketing and R&D tasks, creating and assisting franchisees in implementing more effective business processes, or by avoiding common business blunders, the franchisor may assist its franchisees in reducing the costs.

The franchisor and franchisee must share an honest and trustworthy foundation. It will be challenging to create a solid connection if neither party is committed to honesty and trust. The collaboration benefits both sides in some way. Because their success reflects on the brand, franchisors care that their franchisees are successful. Franchisees must have an input on the important issues as part of the business relationship, which must be a commercial partnership rather than a legal one. The franchisor must carefully consider the franchisee input when making decisions, as is required in a partnership. However, the franchisee must constantly be aware that there can only be one final decision-maker in the franchise system. In a booming, well-run franchise system, most decisions are frequently the result of a consensus. While the franchisor must seriously consider the suggestions and opinions of its franchisees, it alone is responsible for making the final decisions.

Specifically, this finding proposed a proposition:

Proposition 2. Better interconnections between franchisor and franchisees are positively associated with the critical success factors of a franchising business.

5.3. Constant Innovation

A more robust competition results in firms attempting to describe their strategic approach more clearly, such as being a specific price-oriented opponent or further distinguished by greater innovation (

Galvin et al. 2020). The area of competitive dynamics addresses where and how businesses participate in particular competitive behavior and reactions (

Andrevski et al. 2013). Before consumers even realize they need them, franchisors should offer solutions based on their innovation for market development. Long-term client satisfaction is impossible without a willingness to innovate. If the franchisor does not go forward, their business will eventually fail. Throughout years in the business, there comes competition. The rivalry is not limited to firms operating but includes rivalry through value chains and between firms from different sectors (

Gianiodis et al. 2019;

Fawcett et al. 2015). Therefore, continuous innovation is a must to cater for the market and to overcome rivalry.

Past studies have identified a company’s innovation output as a significant factor determining its competitive advantage (

Lee and Yoo 2019). Employee engagement is necessary for continuous innovation; the more involved individuals are, the more their productivity will rise. Employees are empowered to solve problems and provide ideas that will increase the effectiveness of work processes thanks to ongoing innovation. The history of humanity has been marked by the appearance of innovations that have the potential to alter people’s behavior, labor practices, and work (

Galindo and Méndez 2014;

Méndez et al. 2014). Employees will easily transition from passive observers to active participants once they know their suggestions are important, considered, and tested. Constant improvement and adaptation are essential to surviving in a chaotic, competitive world.

However, while simplifying operations and remaining relevant to customers are the goals of every organization, the fundamental measures required to apply innovation continuously are sometimes overlooked. The franchisor may create new products, expand its market share, make surplus profits, and encourage ongoing innovation by actively seeking out, spotting, and promptly acting on each potential opportunity (

Haiyan et al. 2019). Delivery with quality and assurance takes the most outstanding innovations to help jobs run more efficiently while differentiating your business from faster product turn-around times to shorter lead times. Franchisees and franchisors collaborate and actively participate in the innovation process (

Karmeni et al. 2018).

Businesses can enhance their profit, improve their quality, decrease errors, and deliver orders precisely when tiny, positive improvements are made frequently. By amassing knowledge, technological expertise, creativity, and development experience, this strategy helps the organization to foster long-term competition by presenting fresh concepts like product innovation, process innovation, or business model innovation (

Distanont and Khongmalai 2020). All of these actions contribute to a business’ expansion. In addition, an organization will become more flexible by adapting to innovations because we live in a fast-paced world. Being adaptable will ultimately increase the likelihood of surviving competition. Innovations face the risk of becoming obsolete if they are not constantly updated. Continuous and massive capital investment in innovation is required (

Haiyan et al. 2019). Therefore, a franchisor’s business must concentrate on ongoing innovation to thrive and remain relevant.

Implementing efficient process innovation, particularly in product development, is crucial (

Abu and Mansor 2019). It aids businesses in creating new items that may continually satisfy a customer’s demands. As a result, the business will be able to compete worldwide and remain viable. Therefore, the franchisor must design a system that disseminates and institutionalizes the best practices the franchisor has discovered, strengthening and sustaining its service strategy while fostering an innovative and ever-improving culture. The franchisor also needs the cooperation of all ecosystem stakeholders and delivery partners to implement either a product or services plan successfully.

Specifically, this finding proposed a proposition:

Proposition 3. Constant innovation is positively associated with the critical success factors of a franchising business.

Based on the findings and discussion, a framework has been developed for the critical success factors of the franchisor and franchisee, as in

Figure 1.

6. Conclusions

A crucial step in raising the likelihood that a project or program will succeed is identifying the critical success factors and the critical success indicators that support them. It is wise to remember the saying, “what gets measured gets done”. Competent franchisors closely monitor hands to correlate them to critical success factors and to find and support the causal links between the critical success factors and the desired results. The traits of those businesses that effectively changed course during the epidemic are speed and agility. However, fast decision-making and swift action by leaders were also essential. A company’s ability to scale speed and skill depends on its workforce. Leaders who prioritize innovation across the board and set an example of agility by promoting testing, experimenting, taking chances, and trying new things are the first to set the stage for success.

In conclusion, over the past few months, businesses have witnessed higher innovation and pivots in business models that have astounded the industry. However, using these increased rates of speed, agility, and inventiveness in the upcoming standard periods is considerably more challenging. The franchise will ensure its longevity in the market and maximum consolidation to its consumers once these variables are well defined and consequently well-monitored, in addition to loyalty, a better profit, and supplied quality that are the results of comprehensive planning previously developed.

7. The Implication to Academic and Practical

Based on the results of this investigation, both academic and practical consequences can be drawn. Regarding the findings’ theoretical application, the findings revealed themes that have already enhanced the hypotheses about the critical success elements. This paper’s main theoretical contribution is that it brings together the three elements of the critical success factors. The case study has proposed three propositions related to the critical success factors: (i) the existence of a franchisor’s capability is positively associated with the critical success factors of the franchising business; (ii) better interconnections between franchisors and franchisees are positively associated with the critical success factors of the franchising business; and (iii) constant innovation is positively associated with the critical success factors of a franchising business. The propositions developed are based on a qualitative approach, as it has been discovered that using primary data is crucial for formulating the elements within critical success factors.

Moreover, these findings enrich the critical success factors and franchising literature. The aspects discussed in the findings and discussion, the franchisor’s capability, interconnection with the franchisees, and constant innovation, were added to the franchise literature. The key success factors contribute to the critical success factors literature from the perspectives of franchisors and franchisees. A qualitative technique is used in this study to understand better the phenomenon of critical success factors from the viewpoint of the franchisor and franchisee. Additionally, it provides a clearer picture of the successful franchising business process model, its application, its difficulties, and the effects of expansion within the chosen samples.

The current analysis also incorporates two different theoretical stances, agency theory and resource scarcity theory. Doing so adds to earlier research on the critical success factors and theory. For example, the relevance of agency theory involves the relationship between the principal, the franchisors and agents, and the franchisees. The same applies to the resource scarcity theory when there are not enough resources to meet everyone’s needs and there is a scarcity. These theory elements result in a collection of the explanations, forecasts, or recommendations. Therefore, the theory incorporated the literature and findings as a theoretical contribution.

As for practical implications, the findings could be a guideline for policymakers in developing initiatives and development on franchisors. The training and development plan is essentially the timetable or plan which management or higher authorities supply to obtain successful job results. It promotes effectiveness and, as a result, contributes to the expansion of the business. One’s skills, personality, and performance are all improved by training and development. In addition, it would provide a parameter for government agencies to build up good training for franchisors and franchisees.

Finally, the elements suggested by this study would be a guide to franchisors, franchisees, and industry players. It will disclose guidelines so those who want to open a franchise so they can determine whether they possess the necessary qualities. For the time being, the franchisor must thoroughly educate prospective franchisees on the concept of franchising, how it operates, their obligations and rights, and the market repercussions of violating the terms of the contract. These findings have highlighted the essential elements within the critical success of franchisors, the franchisor’s ability, and communication with franchisees. In addition to reducing the opportunistic behaviors and the resulting need for controls and safeguards, a positive relationship between the franchisor and franchisee also provides the chance to increase the profitability by more efficiently combining the resources given by both parties.

8. Limitations and Future Research

The results of this study might not be able to be generalized as the participants were selected based on a particular industry. Additional studies utilizing a longitudinal research design with more respondents, such as non-franchising businesses, are recommended to make the results generalizable and apply these findings to all small- and medium-sized firms. Moreover, a specific case study of a firm to evaluate its critical success factors would be suitable for generating in-depth findings. In addition, the propositions proposed in this study could be tested using a quantitative approach.