1. Introduction

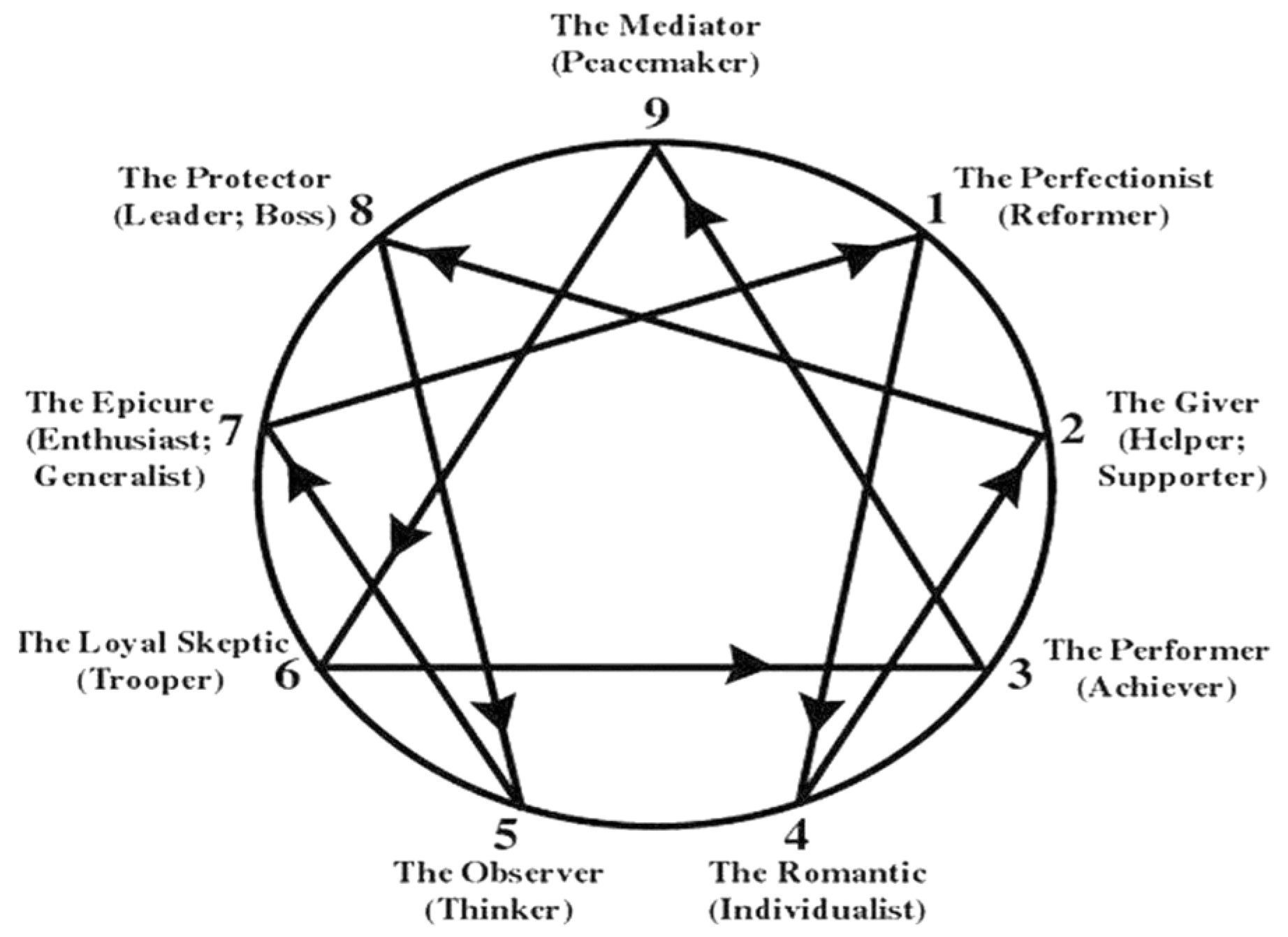

The Enneagram is a personality topology tool or system that formulates nine distinct but closely interconnected personality types. It fosters the idea that people have one powerful or dominant personality type which guides and influences them to interact with the external world, respond to conflict situations, and manage stress. The diagram below (

Figure 1) describes the typical enneagram systems made up of nine different types with their own pattern of behaviour.

We present the enneagram of strategy as a meta-model. Then, we undertake some fine graining which we hope will reveal the components of the meta-model bearing in mind two things; first, that the meta-version is more than the sum of its components and second, the enneagram is a mandala (

Cusack 2020;

Kam and Fluit 2021).

The Enneagram methodology is intended to point to a route towards creative imagination. First, there is the situation now (the system state). The business issue or problem is situated in a particular setting or environment of internal and external dynamics. Since the problem has unique as well as general characteristics, an element of creativity is required. Often managers are required to reconcile opposites; growth versus short-term returns; exploitation of existing assets (to recover sunk costs) and exploration (investment in the discovery of new markets, products, and ways of doing things); operating effectively and innovating; implementing and adapting. Such activities contradict present dilemmas and paradoxes. They require creativity as well as analysis. They require a balance between all the Jungian functions (

Kam 2018;

Akhvlediani et al. 2020).

First, we must remember that the process is continuous. Things never turn out as expected. The internal and external dynamics change. Therefore, there is always a need to adapt. Second, organisations (or individuals) do not pursue single strategies: at any one time, many strategies must be coordinated. This leads to a third observation (

Matthews 1996): Strategy and decisions do not take place at a single point in an organisation. They are distributed, by many decisions and decision-makers (

Navabifar et al. 2020;

Schwarz and Zarrabi 2017;

Dooley and Van de Ven 1999). The research questions are: (1) How can the enneagram approach be adopted systematically to strategic management disciplines? (2) How can its close association be sized using realistic measures?

The Enneagram strategy developed by the authors is an application of the Enneagram to management decision-making. The Enneagram has a long history. In the 20th century, behavioural psychologists adopted the Enneagram as a mainstream tool to investigate personality typologies and personal growth therapy. Many accounts of the personality Enneagram exist in clinical studies, specialist literature, and clinical practice. This research uses the Enneagram as an organisational mechanism to shape organisational conditioning in a systematic approach to reconciling organisational priorities, which are generally complex, specific, and time-bound.

We claim that the mechanics of the nine-pointed Enneagram could be used to discover solutions to many distinct organisational problems as long as the organisation knows how to use both (a) analytical and (b) creative skills through a standard routine. We extend the utility of the Enneagram methodology by integrating dynamic variables such as interdependence, business models, networks (statics and dynamics), and organisational grammar.

2. Literature Review

The personality topology system has undergone significant development over decades by various scholars, strategists, and practitioners. The core theoretical foundation is progressively developed based on the combination of psychological, spiritual, sociological, and philosophical perspectives. It also draws on various schools of thought and traditions such as Jungian psychology and the Sufi tradition. The strategic enneagram approach describes nine distinct but closely associated personality types. Each type has its own set of traits, including motivation, fear, and behavioural pattern. Thus, the enneagram is often used as a tool for building self-awareness, personality development, personal growth and understanding, and building relationships (

Cusack 2020;

Kam and Fluit 2021).

The existing research gap in the literature is the effectiveness of the enneagram that cannot be validated without sufficient empirical evidence across multiple domains. Thus, there is a paucity of literature and much scepticism (

Riso and Hudson 1999;

Rohr and Ebert 2001). The paucity of cross-cultural research can lead to issues with its contextual application, generalization, and customization. Unless the application of the enneagram is extended across hybrid systems or domains, it may lead to inconsistent awareness, education, and training of scholars and practitioners. In conclusion, the enneagram strategy can lead to various incompatibilities with the Enneagram’s perceived validity, its cross-cultural applicability, and training unless supported by conceptual and implementable models (

Kam 2018,

2022). This paper contributes by filling the existing gaps considerably, exhibiting a unique approach to the enneagram application.

The literature validates that there is no unifying theory for the application of the Enneagram. However, various individuals and groups have progressively developed closely associated theories to the enneagram (i.e., the wisdom of enneagram which examines psychological and spiritual growth for the nine personality types);

Riso and Hudson (

1999), and

Rohr and Ebert (

2001) discussed the introduction of the enneagram in Egypt by the Desert Fathers and its revival by a Franciscan in the 14th century.

Currently, the application and development of enneagram ideologies are related to three distinct aspects of enneagram theory, namely: personality development, its structure, and emphasis on personality growth (

Hook et al. 2020). In this paper, we focus on how the enneagram theory and its structure can be applied to complex phenomena in hybrid domains, including but not limited to networks, systems, creative imagination, and supply chains. We also highlight areas for potential development.

2.1. The Enneagram and Organisational Networks

In this section, (i) we distinguish statics and dynamics; statics refers to the state of a system (organisation or firm) at the moment in time, while dynamics describe how the system (organisation or firm) behaves over time; (ii) we describe the role of organisational grammar in a network; and (iii) we present the supply chain as an archetypal network. We distinguish between the system states of an organisation and its trajectory over time. Clarifying the distinction before we get into more technical details with an example is a good idea. Here, we illustrate system states with concrete examples. They are actual situations. Hence, there is a need to preserve anonymity (

Kartikeyan 2020;

Blose et al. 2023).

The state of A’s company (the system state) is that they produce a variety of security services (some high-value services, corporate and personal protection, and some lower value-added, such as alarms and security guards). The system was initially static at the beginning of our executive programme, but the problem A faced was to reorganize and restructure so that; (a) he could hand over day-to-day operational problems to other managers and (b) devote more time to longer-term strategic issues (the trajectory over time).

Another executive, B, manages part of a holding company that produces and sells low-value medical supplies. The state is this: Customers require quick responses to their orders. Production takes time, so holding stocks of goods (working capital) is necessary. There are many competitors. However, corporate headquarters, as is often the case with holding companies, are unwilling to tie up much cash in working capital. In this case, corporate debts must be refinanced at a relatively high-interest cost. Thus, there is a dilemma; orders are delayed, and customers are lost. Therefore, B cannot meet sales targets. However, if he holds higher stocks, debt levels cannot be reduced. He is pessimistic about future system states.

The Enneagram and Organisational Dynamics

As we noted, these are temporary states, subject to change because of inner and outer dynamics. Grammar is also subject to change; if payoffs are unsatisfactory for one reason or another, this will bring about change.

As shown in

Figure 2, the state of an organisation in the present time is represented as an intersection of inner and outer dynamics with payoffs, all expressed in the context of grammar. Inner dynamics (ID) are an organisation’s assets, capabilities, and competencies. Outer dynamics (OD) include forces of competition and cooperation, and interacting macro forces; economic, environmental, governmental, legal, technological, and so on (

Tlemsani 2010,

2020;

Tlemsani and Matthews 2010;

Tlemsani et al. 2022).

The system state is not an equilibrium state. It shows where an organisation happens to be at a moment in time. It is an intersection of dynamics, payoffs, and grammar. Note that the system state is not a point but an area. We should think of the system state indicated in the diagram as a vector that includes the relevant aspects of inner and outer dynamics, grammar, and payoffs that exist at a point in time.

2.2. The Enneagram as Meta-Model and Organisational Grammar

The enneagram model (and its sub-model, the meta-model) typifies the first type but adds another dimension. The purpose is to tune into the creative imagination of individuals or groups. In that sense, the Enneagram model is a Mandala. Mandalas are used in some Buddhist traditions as objects of contemplation. The nine-point enneagram (

Figure 3c) Mandalas are symbols used in Hinduism and Buddhism to focus attention, an aspect of mindfulness, and develop creative or active imagination. Geometrically, enneagrams are a class of nine-point figures.

The strategic enneagram referred to here is made up of an inner triangle (

Figure 3a) and an irregular hexagon, a six-point figure (

Figure 3b). It originates in Sufi psychological and mystical teaching, the Pythagorean number system, and traditional religions. In the 20th century, the enneagram was developed by Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, and John Bennett. The Strategic Enneagram is symmetric. It is based on recurring decimals; 1/3 (0.333 …) 2/3 (0.666 …) and 3/3 (0.999 …) expressed in the inner triangle, representing the meta-model and hexagram based on 1/7 (0.1428571 …), 2/7 (0.285714 …), and so on.

As a mandala, the Strategic Enneagram, illustrated in

Figure 3, is used to focus attention, linking it to mindfulness and developing creative or active imagination. Mindfulness has been recently imported into management thinking from Buddhism as a technique for reflection and managing stress.

The Enneagram methodology is a framework for analysing strategic problems and designing creative strategies, combining intellect (analysis and logic) and imagination (creativity and intuition). Application of the Enneagram mandala to management to business and strategy reflects the proposition that spiritual and mystical aspects of life are not separate from material and practical aspects.

Creativity probably cannot be taught. However, it can be encouraged. The Strategic Enneagram as a mandala is a way of evoking creativity in individuals and groups. It incorporates strategy, mindfulness, and creativity (

Kam and Fluit 2021;

Kam 2022). The phrase strategic process is a series of states of a system over time. Thus, we begin by considering the process which we think of as being to some extent deliberate and second the state itself, represented by the inner triangle in

Figure 3a. In

Figure 3, both the process and system state are embedded in grammar. The process is traced out by the hexagram 1, 4, 2, 8, 5, … It has a cognitive aspect (1, 4, 2), an implementation aspect (8, 5, 7), and, since the situation is dynamic and adaptive, a learning process (7, 1) relating what is implemented to what is intended and what values were intended and what was achieved (2, 8). The enneagram is symmetric around risk which arises when the purely cognitive is implemented. Purely cognitively, anything is possible.

Networks and Grammar

Grammar determines (a) the nodes (the aspects of the world we choose to focus on) and (b) connections (how the nodes are linked). Nodes correspond to the parts of speech (nouns, verbs, adjectives, prepositions and so on) in ordinary grammar. Linkages correspond to the syntax (grammatical rules such as declension and conjugation) that connects parts of speech.

Figure 3 can be seen as a picture of five different grammars; a and f are connected networks, b, c, and e are only partly connected, and c is a star-shape network emanating from the central node A. Linkages can be thought of in the static sense as synergies or in the dynamic sense of feedbacks (

Feltsan 2019). Incorporated below are some of the characteristics of grammar (

Akande 2009;

Kim and Kim 2010).

If we think of strategy as the interaction of interdependent networks (inner and outer dynamics and payoffs), Grammar determines the nature of the interactions; which parts (or nodes) are linked and how they are linked.

Grammar is a complex form of conditioning. It includes rules, laws, regulations, cultures, ways of thinking about problems, and so on. It includes formal and informal routines (R), the architectures that bind routines together (A), influences of national and corporate culture (C), and mindsets (MS); the acronym MARCS is a useful way of describing the influence of grammar.

Grammar is a complex adaptive system (CAS); its elements (nodes) interact with one another, conflicting with, reinforcing, or dampening one another whilst still retaining an internal cohesion.

2.3. Interdependence and Enneagram Methodology

The Enneagram methodology, which is outlined here, spans both requirements of management in a new era. Most of the analytic techniques taught in business schools can be shown to be sub-models of the Enneagram methodology, which is a general model. In addition, the Enneagram methodology provides a technique for encouraging creative imagination. To be credible to businesspeople, we need to focus on practical aspects. Can the methodology be used to increase sales/profits? Can it expand the capabilities of the individual and team? Can it help managers achieve the task as defined above? We maintain that the answer is yes and attempt to show why this is so in this paper. The previous section outlines some theories. The remainder of the paper focuses on practical issues (

Cusack 2020;

Petsche 2016). According to (

Edwards 1992;

Moore 1992;

Schwarz and Zarrabi 2017) the rationale for the Enneagram methodology is as follows.

Thinking, feeling, analysing, and responding are conditioned or programmed.

Conditioning or programming is achieved as a result of a mechanism that we call organisational grammar (grammar).

Organisational grammar has positive and negative aspects: both are necessary.

It is functional (positive), enabling us to make sense of the world. It introduces a degree of stability and predictability into the world.

However, it is a form of conditioning/programming (negative). It limits creative imagination.

There are many alternative organisational grammars, i.e., new ways of thinking, feeling, analysing, and responding.

Christian mystics, the Kabala, Buddhists, and Sufis have made the point about conditioning in a variety of ways for generations.

Some computer scientists make the same point in a different way: that the possibility exists in the near future of creating spiritual machines capable of creative imagination.

Some scientists see the transition to alternative organisation grammars as happening around 2040/2050. They speak of the Singularity.

2.4. The Enneagram as a Network—Statics and Dynamics

The distinction between statics and dynamics is convenient because it enables us to distinguish where an organisation is now (the system state) and where it may be in the future (its path or trajectory over time). Although the distinction between statics and dynamics is useful, it is artificial. The present moment is never static: it moves continually into the future. A business is subject to dynamic (constantly changing) pressures at any time.

Nodes in

Figure 4 could be interpreted in many ways; as elements of outer dynamics (A = political, B = economic, C = technological … D = creativity and E = innovations). Alternatively, they could refer to inner dynamics (marketing, sales, operations, logistics and so on, in the value chain); or they may represent the tangible or intangible assets of a firm; or they might be interpreted as payoffs to different stakeholder groups (A, B, C … stand for profits, returns to shareholders, creditors, employees, the community, as taxes, or to customers as quality products or services, the environment); or they may be different aspects of organisational grammar.

The Enneagram is a connected network.

In

Figure 1 the system state corresponds to the numbers 3, 6, and 9. The trajectory corresponds to the other numbers 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8.

Note an important aspect of the trajectory (process) Enneagram: It is a connected network that is ordered 142 (cognitive), 857 (action), 142, 857, and so on since decisions or strategies and continuous processes through time.

Mathematically, the Enneagram is based on the idea of sevenths (1/7, 2/7, 3/7, and so on). Translating sevenths into fractions, 1/7 becomes 0.142857142 … an infinite series. The fraction 2/7 is 0.285714285 …, and so on. This mathematical aspect of the Enneagram is why it operates like a mandala. In some traditions, a mandala approaches creativity (

Khavul et al. 2010).

System States and Trajectory; The Enneagram Mandala in Time

The system state describes where an organisation is now. It is like a snapshot of a moment in time. A complete description of a system state would specify all the inner and outer dynamics, the payoffs generated to stakeholders and the state of organisational grammar. The trajectory is the path over time as inner and outer dynamics, grammar, and payoffs change. The trajectory describes the succession of system states that occur over time. If St[0] describes the system state now t(0), the succession of system states is St[0], St[1], St[2], …, St[n].

Economists like to talk about equilibrium. However, it is mistaken to think that a system state is an equilibrium. There are too many variables and too many decision-makers to consider, the elements of inner and outer dynamics, payoffs, and so on. The system state is simply the state an organisation happens to be in now.

We could think of equilibrium in connection with the system state as a Nash equilibrium; Nash equilibrium is a situation in which no one has the incentive to change their strategy so long as no one else does. Equilibrium as a trajectory could be thought of as an evolutionarily stable strategy; a set of agreed strategies that could not be upset or disturbed if a small number of decision-makers diverted from the agreed strategy.

2.5. The Enneagram and Supply Chain Network

The nodes are suppliers (raw materials and energy, equipment, labour, management and so on), the firm’s value chain in question (showing how it adds value), distributors, retailers, and final customers. As demonstrated in

Figure 5, connections summarize transforming inputs from suppliers into outputs distributed to final customers, distributors, and retailers (

Elsaleiby 2019).

In I’s company, the state is such that outer dynamics in the company are seasonal: meaning that there is an uneven pattern of revenues over the year. In most companies inner and outer dynamics as well as organisational grammar are problems, meaning that payoffs (profits and margins) are being squeezed. The recession (outer dynamic) is a problem, and such problems are likely to become more and more intense. As the world macro situation worsens, competition will intensify; nations will try to export their way out of recession. Of course, every country cannot do so (exports = imports in total). Often regulation brings new problems. Beer companies, for example, have regulations to limit the consumption of alcohol. Then, there is the recession (outer dynamic) and grammar in the form of low management skills of retailers/partners; all these things squeeze sales and profits (and other payoffs). Consider the firm as a transformer of inputs into outputs via the supply chain. If the arrows pointed left to right instead, this would indicate cash flows from final customers to profit margins and costs (rents, wages, and capital costs) in the supply chain. Alternatively, the left–right arrows could indicate financial accounting relationships in the supply chain.

Figure 5 presents the connectors as two-way messages: in one direction, supplies are transformed into final outputs of consumer goods and services via distributors and retailers; in the other direction, customer cash is absorbed into profit margins and costs of production at various stages in the supply chain (

Figure 6).

The problem of capitalism has never really been one of supply. It is intrinsically dynamic. The problem has always been having demand keep pace with supply. The answer is sometimes yes and sometimes no. When it does, we have economic growth. When it does not, we have stagnation and recession. We trace the roots of the current Great Recession fundamentally to problems of deficient demand. Marketers understand the importance of demand. That is why such a high proportion of a firm’s expenditures are on marketing and promotion (and built-in obsolescence so that products wear out and must be renewed). The great economist Keynes recognised the primary importance of demand (he called it Effective Demand). He recognised that deficiency of demand brought instability and required that to void recessions and depressions governments would have to fill the gap left by insufficient investment demand by corporations and consumer demand by households by creating demand through government expenditures. However, Keynes has been forgotten. We could argue that the Keynesian revolution never happened. Sooner or later, governments will have to recognise that government expenditure (government demand) is the precondition for the survival of their economic and social systems (

Figure 7).

2.6. Meta-Model

The meta-model is a way of describing the current state of an organisation. The current state never lasts for long. It is always subject to change. Hence the following categories are identified in the meta-model shown in

Figure 8.

An organisation cannot happen without formal and informal rules, including laws, traditions, regulations, systems and structures, cultural and historical influences (including religions), and the mindsets and ways of thinking and doing common to individuals and groups in an era, nation, region, society, and family. The examples in the previous sentence are organizing principles. In computer programming, they are described as Standard Operating Procedures. They make organisations work. All these organizing principles are represented by artefacts; architecture, the layout of cities, works of art, the creative arts (music, literature, cinema, theatre, sculpture, new media), consumer goods and services, and the technology of an era; generally, what we see and experience around us that changes like all things over time. We refer to these organizing principles as organisational grammar; grammar, for short. Grammar summarizes the core organisational principles that underlie outer and inner dynamics and payoffs.

Outer dynamics are outside forces; for example, competition, new and often disruptive technologies, political, economic, ecological, etc. Organisations live in a global capitalist environment (sometimes described as neo-liberalism), which evolves and changes. Grammar, and all the informal and formal rules, including culture, referred to in the previous paragraph, is to some extent homogeneous (global similarity), spread by information networks, media, advertising, the internet, and social networks created by science, technology, and the arts.

Inner dynamics include tangible and intangible assets and the organisation’s dynamic capabilities (competencies). Tangible assets include physical capital, human beings, natural resources, access to finance (debt and equity), access to information and data, and tacit and explicit knowledge contained in an organisation. Intangible assets include brand, reputation, and corporate image. Included in intangible assets are the elements of corporate culture; mindsets, ways of thinking and doing by individuals and groups, and their assumptions and traditions (

Mohamed Hashim et al. 2022a).

Payoffs to stakeholders include financial returns, measured by profit, EBIT, CAGR, sales, market share, and many financial ratios. Capitalism focuses on returns to shareholders; market capitalization, returns to equity, and debt liabilities, for example, and teachers often parrot the importance of shareholder value. The enneagram approach to strategy is viewed as a meta-model that provides a home and a place for these toy models. The meta-model is a sub-model of the full Enneagram model. It focuses on elements of the system state of an organisation, inner and outer dynamics, payoffs, and grammar.

Figure 8 illustrates the basic elements of a system state as a network of relationships between inner (ID) and outer dynamics (OD), payoffs (P), and organisational grammar (G), the meta-model.

The term

meta is used because (as we see below) many economic and management models relate to one or other of the categories of the meta-model. This picture is rather misleading in that it treats the four elements of the meta-model separately. No diagram can give a complete picture, but the purpose of

Figure 9 is to relate the meta-model to some of the standard economic/strategic models (

Koutsopoulos et al. 2020;

Boritz and White 2016).

Figure 9 is an archetypal picture of the meta-model of a company. Some companies’ suppliers are equipment manufacturers. In others, for example, consultancy companies, the key suppliers are people with the right skills, and the company sells directly to the final customer: a Business-to-Business relationship. In security companies, the relationship is both Business-to-Business and Business-to-Customer. Some companies are retailers, distributors, and sellers to final customers.

Figure 9 must be adapted to suit the situation. The company and its value chain are at the centre of the picture. The main activity in the value chain may be bottling and distribution. In a retail company, the main activities are sales and marketing and, most importantly, working capital management. In a furniture design company, the main activities may be designing tailor-made products and layouts. Very often, add-on services offer the highest margins, e.g., retailers who offer an extended warranty, phones, and IT companies that offer apps (

Mohamed Hashim et al. 2022b).

3. Methodology

This paper uses a combination of theoretical, exploratory, and descriptive research methods to evaluate the enneagram’s adaptability. The methodology adopted two distinct parts. The theoretical part is signified by providing a critical review of the literature and the meta-models. The theoretical review synthesizes the adoption of an enneagram in the organisation using analytic and creative imagination. It stems from the idea that the solution to business problems requires creativity as well as analysis. Thus, the methodology deployed in this paper is an ontological analysis. We captured, described, and examined different meta-models, approaches, real-world examples, and creative imaginations using Enneagram. Therefore, the Methodology Section exemplifies how Enneagram as a mechanism can help various organisational reconciliations.

Let us denote the real world of everyday experience as [R] and the spiritual world as [Ω]. [R] and [Ω] are distinguished by having different organisational grammars (grammars). The purpose of grammar in [R] is (a) to enable us to make sense of the (real) world and (b) to introduce some order and stability into it. Other spheres of Being, which we summarize as [Ω], have different grammars.

One proposition of our analysis is that creativity in [R] involves being able to see the world through a different grammar. Put another way, spiritual techniques in Buddhism, Zen, Sufism, and so forth enable the individual to access (perhaps briefly) an alternative grammar.

A second proposition is that issues in business, such as innovating and developing new products, markets, and technologies, are not so different from the issues facing the painter or the sculptor in that they involve creating something new.

Thus, by applying a well-aligned methodology (theoretical, exploratory, and descriptive), we developed, estimated, and regularized a cross-sectional enneagram approach to strategy. It is important to set out the methodology as a process over time, as described in

Table 1.

The need for urgent creative analysis and the importance of setting out a dependable methodology (captured in

Table 1) can be expressed in a mandala, such as the diagram below (

Figure 10). The mandala captures and summarises the holistic approach of the Enneagram methodology. The enneagram methodology applied to reconcile organisational activities is shown in

Table 1.

Figure 10 represents the nine pointers of reconciliations adopted by organisations to shape and react themselves in different conditions. The Enneagram methodology is explained further in the next section. We note now that it draws on many disciplines and intellectual concepts, such as networks from physics as well as disciples such as Buddhism, Zen, and Sufism which have much in common and are concerned practically with developing the creative capabilities that most people possess (

Moore 1992;

Kern et al. 2011). Thus, we attempted to explore how the Enneagram methodology as an organisational tool could be used to achieve organisational conditioning/determines priorities.

4. Results

The enneagram approach to strategy is widely used in the personal and spiritual growth, personality development, and psychological development domains (

Hook et al. 2020;

Riso and Hudson 1999). That means the enneagram is viewed as a powerful tool for self-discovery, a personality model that describes nine distinct types of people, each with its own traits, motivations, and behaviours. However, its applicability beyond these domains continues to be a grey or underdeveloped area.

By examining the results derived from the existing literature, we have assessed how an enneagram approach can be used in business strategy, organisational decision processes, and interventions. We relate the application specifically to (i) organisational network, (ii) organisational dynamics, (iii) organisational grammar, and (iv) network and grammar. Our evidence derived across various domain indicate the enneagram could be applied/adopted as a robust tool in organisational interventions at various levels and in multiple dimensions, i.e., at an individual level, organisation level, and society level.

The results of interdependency and the enneagram methodology indicate that the combination can be applied to trigger creative imagination in business management. Thus, the application of the enneagram can be widened to static and dynamic system states. Further, this paper also explored the effectiveness and outcomes of the enneagram-based interventions in supply chain and organisation grammar. It showed a road map of how the application of the enneagram can be transformed into meta-models. Thus, these results justify the effectiveness of enneagram-based intervention, which can be useful in improving payoffs, enhancing communication, examining the strengths and weaknesses of organisational networks, and gaining productivity.

Another way the Enneagram approach can be applied to strategy is by identifying potential conflicts and finding ways to address them. Each Enneagram type has its own set of strengths and weaknesses and understanding these can help teams/organisations work more effectively together.

The Enneagram approach to strategy has several key findings that can help organisations, individuals, and teams improve their strategic planning and decision-making processes. Some of these findings include the following:

Each Enneagram type has unique strengths and weaknesses that can be leveraged in the strategic planning process. By understanding these traits, individuals and teams can optimize their performance and make more effective decisions.

Leveraging Enneagram types of problem-solving and decision-making in different ways. For example, some types may be more analytical and detail-oriented, while others may be more creative and innovative. Understanding these differences can help teams make more informed decisions considering different perspectives.

Improved leadership: Leaders who understand the Enneagram approach can more effectively motivate and manage their teams. By understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each Enneagram type, leaders can assign tasks and responsibilities that play to each team member’s strengths.

Overall, the Enneagram approach to strategy can provide individuals and teams with valuable insights and tools for improving their strategic planning and decision-making processes. By leveraging each team member’s unique strengths and perspectives and fostering a culture of self-awareness and growth, teams can create a more successful and fulfilling work environment, which can contribute to a more successful and effective strategy. The theoretical implication of the enneagram approach is that it confronts the traditional personality view that visualises the individual as fixed and static. The enneagram sees that personality development is progressive and dynamic, and it can be shaped effectively by fostering self-awareness and experiences. It also stresses the importance of identifying and addressing the motivation and fears that may steer individuals. Another implication of the enneagram for practical use is that it can be utilized as an effective tool for personal development, growth, and fostering relationships. When the topological tool is applied, individuals can gain deeper insights about themselves and others, and improve their compatibility in building relationships.

5. Discussion

This section develops a constructive discussion derived from the existing literature, its philosophical application, and potential usage in the strategic management discipline. Further, it provides a set of principles via graphical representation to discuss the future state.

5.1. From the Meta-Model to the Full Enneagram Model

Figure 11 transforms a system state at any time

t into three possible trajectories over time: three possible alternative future scenarios. The diagram is a simplification. First, there are many possible scenarios; many of them cannot even be anticipated. The future is a source of risk and uncertainty. Second, as noted below in

Figure 11, the system state should be represented by a vector in the space of many dimensions rather than a point in three-dimensional space. However, the diagram does provide a bridge between system states and trajectories over time (

Desmarais et al. 2020;

Mohamed Hashim et al. 2021;

Hellany 2006).

5.2. The Enneagram Mandala and Management Strategy

Creative imagination (new ways of thinking, analysing, feeling, and responding to situations) requires stepping outside conditioned patterns and entering an alternative grammar. Hence, both

Figure 12 and

Table 2 are set in the context of organisational grammar.

Thus far, we have made several propositions. Now we add two more. The first is that people normally do not make decisions in the way we like to imagine. The second is that many who are called leaders do not lead; they are dependent upon the society that gives them power rather than true leaders or creators.

The apparent contradictions, i.e., decisions that are not really decisions and leaders who do not lead, hinge on grammar. Grammar is conditioning or programming. It enables us to make sense of things (according to the grammar we adopt) and introduces stability and organisation. Here, we focus on what we called the real world [R] in

Section 3. Many decisions and strategies are conducted in a way that is completely programmed by conventional grammar. Sometimes this is good enough, but when managers are faced with problems that are extreme, unique, or require creativity, as often happens, then it is not enough. They must create a different grammar.

Similarly, people in a position of leadership are often conformists with respect to conventional grammar. In being conformists to conventional grammar, they are inauthentic. Such people, CEOs, political leaders, and so on, think they are leading and think their role is critical when, in fact, they are merely being swept along by events. Tolstoy portrays Napoleon like this. Napoleon thinks he is controlling events, but he is being swept along by many seemingly trivial circumstances, the actions and moods of individual soldiers, small accidents, the weather, randomness, or luck. Leaders have a habit of attributing their successes to themselves and failures to others or to bad luck. The components of

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 are explained in a linear version in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

6. Conclusions

This paper extends the meta-model to the Enneagram model and introduces changes in system states over time and the role of decision-making. The Enneagram is a mandala that encourages imagination and creativity as well as analytic thinking. Early sections repeat some things from an earlier paper which dealt mostly with the situation now when the underlying dynamics are imagined to be frozen. They never are frozen, but the simplification is useful. The distinction between a moment in time and transitions over time is convenient but artificial. We must always think of time as an interval. There is no timeless moment, only intervals, long or brief.

Previous research findings have indicated that in a few cases it was not possible to generate results which support the nine factors or points of the enneagram (

Hook et al. 2020). There is a paucity of the literature in terms of identifying a basis to cluster the nine standard types of enneagrams. Further, how these nine types are applied to various domains and their secondary facets (the logical connection between the wings and movements) continue to be a grey/underdeveloped area.

Strategic management appreciates the growing popularity of the enneagram specifically in the niche disciplines. We emphasized this phenomenon by integrating/scientifically linking the enneagram typology with the organisational network, grammar, supply chain, and creativity. It establishes the vital connection of enneagram to closely associated but extended/hybrid business disciplines. We attempted to provide a balanced scientific view interconnected with distinct enneagram practices; thus, it offers an opportunity to learn from a new hybrid disciplinary tradition. The applicability of the enneagram is limitedly established with rigorous research in the organisational literature; still, the enneagram is under-researched, neglected, and active mostly in unindexed journals. This reveals its limited reputation among scholars and practitioners. As stated, accumulated conceptual and scientific evidence indicates that the reliable application of enneagram can be extended to various organisational disciplines such as networks, grammar, supply chain, and creativity. The application of an enneagram is relatively influenced by contextual setting, or the pattern of connections.

In a certain discipline (i.e., supply chain) the methodology to assess the pattern of connection/the architecture required to conclusively examine the accumulated impact requires a new/innovative approach. Recent research used cluster analysis to determine the pattern underlying the nine interconnected archetypes. Rigorous, diverse, and particularly mixed method research is required to (a) shape the operationalization of the enneagram and (b) align enneagram theory with other disciplines, endorsing its extendibility to hybrid disciplines. We conclude that the Enneagram approach to strategy may serve as a practical and effective tool that can be utilized to shape the development of a new body of knowledge in strategy, organisational grammar and networks, organisational systems, and creative disciplines.