Entrepreneurship’s Creation School and Its Comparison-Based Approach: Assessing the Lessons for Theory’s Progression

Abstract

:1. Introduction

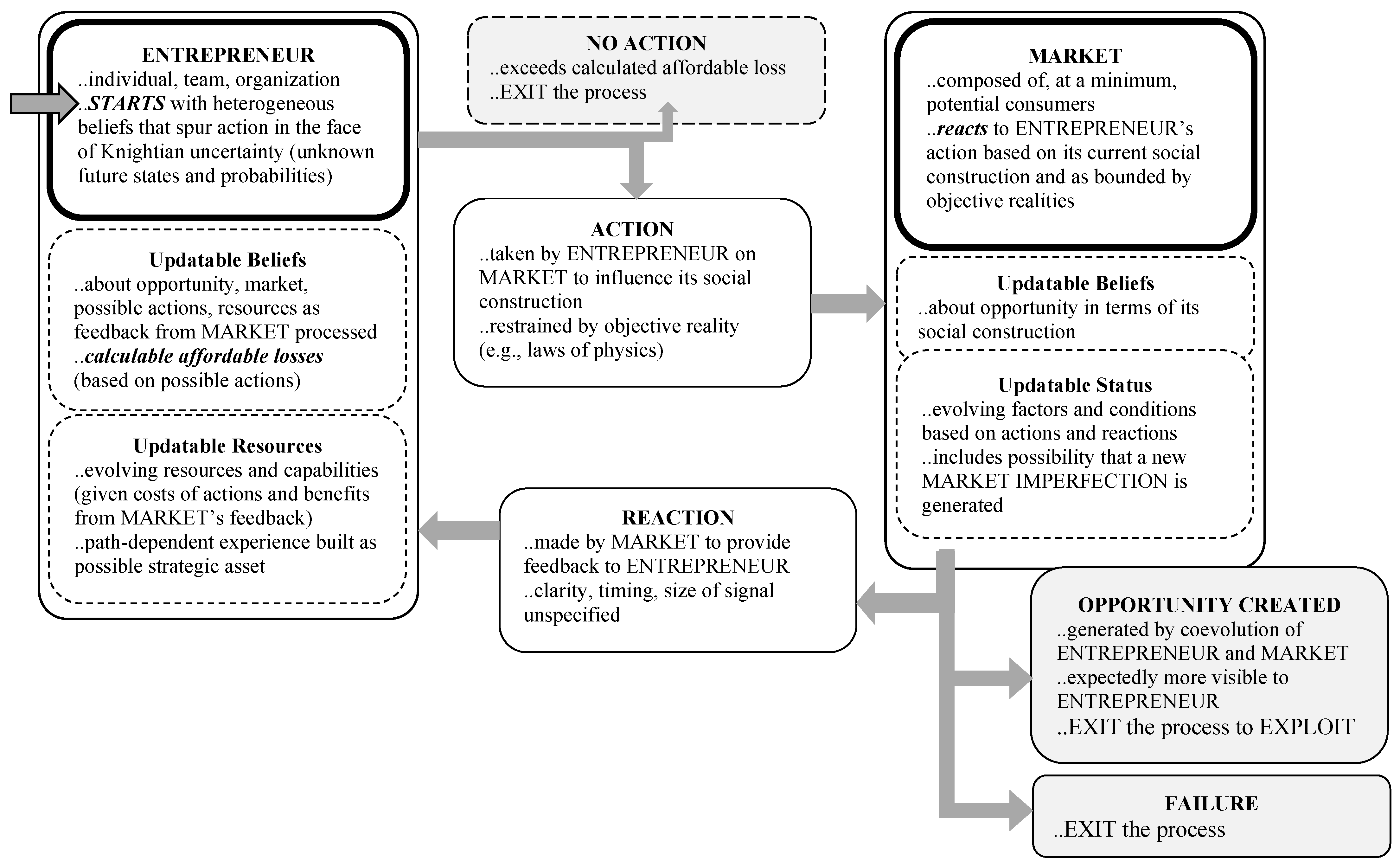

2. A Critical Assessment of the Creation School

2.1. The Creation School’s Process Model

2.2. The Framework for Evaluating a Proposed Theory

2.3. Assessing the Creation School across the Explaining Criteria for Theory

2.4. Assessing the Creation School across the Establishing Criteria for Theory

2.5. Assessing the Creation School across the Experiencing Criteria for Theory

2.6. Assessing the Novelty of the Creation School’s Ideas

2.7. Assessing the Questions Raised by the Creation School for Entrepreneurship and Strategy

3. Comparison-Based Theorizing

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The 3E framework is independent of theory type, as explained in Arend et al. (2016). It has been applied to multiple theories and is based on established criteria proposed by many management theory scholars in top journals over decades, with its core in Dubin’s (1969) work. We note that one of the creation school’s founders even submits her school to Dubin’s criteria (Welter and Alvarez 2015; pp. 1402–3), thus verifying that the school’s processes can be assessed under criteria like the ones applied here. |

| 2 | Note that the definition of the main unit—the EM as a strategic actor seeking to exploit an opportunity (Alvarez et al. 2013, p. 302)—is problematic because it not only assumes the pre-existence of a different unit—the exploitable opportunities—but one that the school is trying to explain the existence of. |

| 3 | Note that the EM and the market are each likely to be entities embodying many individuals, making the updating of beliefs, internal social constructions, decisions, calculations, and actions potentially complex (as involving interdependent interactions among those embodied individuals). Given that there exist extensive literature modeling such complex internal phenomena, it should not be trivially glossed over. However, the current model simply overlooks those supporting processes, even though they appear at the same level of analysis as the primary process. |

| 4 | Note that the example exogenous shocks listed in the creation school (i.e., changes in technology and consumer demand, and in political and social institutions—see Alvarez et al. 2013, p. 305) are all generated by intentional human actions that are endogenous within their own markets, regardless of if they also have shocking effects in outside markets that may be exploitable there. This raises the question that, if all opportunities are created by human action, even the ones that the creation school labels as discovery opportunities, then the school-to-school boundary would be non-existent as only one process appears to drive all entrepreneurial activity—the process that continuously generates incomplete information. |

| 5 | There are a myriad of further questions relating to the logic of the creation school that should also be considered, including: What do the dynamics of the co-evolving process look like? How much does the market co-evolve rather than simply react through judgment (Garud et al. 2014)? How is disinformation from customers and rivals filtered out? How can entrepreneurs use disinformation and other “cheating” tactics to gain an advantage in this context (Arend 2016)? What is the learning process of the EM regarding the various pieces of information that are initially incomplete but evolve toward being sufficiently complete so as to be considered only “risky”? What does that initial decision about the scale, timing, and characteristics of the first action look like, and how do resource constraints affect that? When and why do the gains become estimable—is it the unknowability of the states or their probabilities that is the issue along the way? Why aren’t other decision items unknown, like possible alternative actions, or the payoffs of those? Why are losses not malleable, for example, by receiving payments and shared liability from partners or consumers? Why does it matter whether the paths to opportunity formation are dependent or unique, if the opportunity itself becomes known when formed? How does forming the opportunity influence the ability to exploit it otherwise? |

| 6 | Note that the school does hint at potential hypotheses—based upon statements about (i) several team characteristics that would likely lead to success in their process (see Alvarez et al. 2013, pp. 309–12); and (ii) the lower degree of non-causal-ambiguity-related entry barriers built. None of those have been tested. |

| 7 | Work that attempts to test the creation school includes one piece by one of the school’s authors and one independent piece. Hmieleski and Baron (2008) do not directly test the school; their H2b is about promotion, not creation. Alvarez et al.’s (2015) study consists of one historic case not involving a created opportunity but the evolution of a long-existing product (i.e., king crab) through innovations in processes and in legitimization. No market failure existed; their P1 is simple self-interest, not creation, and their P2 involves generating shared beliefs, which is an activity that is not solely attributed to the creation school. |

| 8 | Note that the most important practitioner concern remains a mystery in the creation school—that of identifying the origins of the EM’s differentiated initial belief that sends the EM down that path to forming and then exploiting that new opportunity. |

| 9 | For human-action-based phenomena (as with the case here), note that the validity of those observations also needs to be assessed (e.g., Locke 2007; Pentland 1999). |

| 10 | Besides failing to cite similar work, the creation school also avoids citing (and discussing) relevant work that questions the kind of research that they do cite. For example, the possibility that “the evolution of the ideas can lead to failure” is overlooked, which is somewhat dangerous if we care about truth and social welfare (e.g., Rowbottom 2010). The overall equivalence of evolutionary realism with scientific (aka objective) realism—as even admitted to by Campbell (1974, p. 451)—is downplayed for the sake of contrast. Also un-discussed is that the evolutionary process occurs in a non-equilibrium system (Buchanan and Vanberg 1991). And the possibility that the process is driven by randomness—which is naturally present in real complex systems (Allen 1988)—is not fully considered (i.e., as this process is based more on luck than on entrepreneurial skill). |

| 11 | We note that all “opportunity schools” are open to critique—the creation school and effectuation criticize the discovery school while also being critiqued. Each school offers both strengths and weaknesses, and their advocates should be willing to assess such theorizing along the 3E criteria (or equivalent) in order to see where improvements can be made. |

| 12 | The recent proliferation of inaccurate versions of what KU is, is a product of adhering to the creation school rather than considering alternative theorizing. There are several potential dangers to continuing such a “creation school perspective” that confuses “unknowability” with “what is initially unknown but is actually knowable”. First, if KU is not actually required for the creation school’s entrepreneurial activity, then the main challenge represented by known-unknowables—being the non-optimizability of any decisions involved—is avoided when it should not be, and the main challenge represented by knowable-unknowns—the highly complex modeling required to capture the competition it involves—is also avoided, but should not be. Second, and to the latter, if the end-to-end profit-making process that requires uncertainty-reduction is not fully and explicitly explained, then, from a theoretical standpoint, there is no actual profit guaranteed—as not all of the steps can be formally scrutinized to prove that any one venture can succeed—and, as such, from a practical standpoint, there is no real prescription to follow, as managers cannot implement plans that are incomplete. |

| 13 | We analyze the comparison-based approach because it is a relevant and important addition to theorizing—it is used in the creation school and in effectuation—two recently proposed partial theories that have received significant attention in our field. And one could contend that one of its key traits—that of “strawmanning” a targeted pre-existing theory—has been more visible in many related fields (e.g., with the arguable strawmanning of the individual traits stream by the nexus model in entrepreneurship, or of the resource-based view by the dynamic-capabilities view in strategy, or of game theory by behavioral models in economics). |

| 14 | Violating the simplifying assumptions of homogeneity, informational completeness, and rationality is often nightmarish in terms of modeling the consequent complexities and non-closed-form-solutionability that arises. However, it is often necessary to do so in order to make progress in building better theory; the alternative of building interesting but informal “stories” is simply not science. |

| 15 | Another effective tactic of the recent comparison-based approaches, as a further means to draw attention and contrast to themselves, has been to tease that their processes have “solved creativity”. Of course, that can never happen; in fact, such alternatives do not actually give the creative process the full respect it deserves, never getting into the realities of its difficulties, especially at the individual level (e.g., as more fully described by experts as in the case of its multi-stage conceptualization in visual artistry—see Ehrenzweig 1967). |

| 16 | In addition to the three primary papers that define the creation school, pieces like Wood and McKinley’s (2010) add some further details (e.g., more boundaries). That said, they also miss several crucial elements (e.g., how competing social influencing works); make several questionable assertions (e.g., that opportunity ideas do not require market failures); and contrast to a strawman version of the discovery school (e.g., presuming, incorrectly, that successful opportunity exploitation does not involve the entrepreneur and their social capital, and that marketing is not used in the latter part of the discovery school’s full process). Therefore, while such papers under the creation school may offer some alternative, specific details that the discovery school does not (e.g., on how entrepreneurs process opportunity abandonment), that does not in and of itself make good theory, or even necessarily provide new insight into the larger picture (e.g., given psychological research also deals with the personal processing of failures). |

References

- Abell, Peter, Teppo Felin, and Nicolai Foss. 2008. Building micro-foundations for the routines, capabilities, and performance links. Managerial and Decision Economics 29: 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aldrich, Howard E., and C. Marlene Fiol. 1994. Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review 19: 645–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, Howard E., and Martin Ruef. 2006. Organizations Evolving, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Peter M. 1988. Evolution, Innovation and Economics. In Technical Change and Economic Theory. Edited by Giovanni Dosi, Christopher Freeman, Richard Nelson, Gerald Silverberg and Luc Soete. London: Pinter Publishers Ltd., pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., and Jay B. Barney. 2007. Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 1: 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., and Jay B. Barney. 2010. Entrepreneurship and epistemology: The philosophical underpinnings of the study of entrepreneurial opportunities. Academy of Management Annals 4: 557–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., Jay B. Barney, and Philip Anderson. 2013. Forming and exploiting opportunities: The implications of discovery and creation processes for entrepreneurial and organizational research. Organization Science 24: 301–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., Jay B. Barney, Russ McBride, and Robert Wuebker. 2017. On opportunities: Philosophical and empirical implications. Academy of Management Review 42: 726–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, Sharon A., Susan L. Young, and Jennifer L. Woolley. 2015. Opportunities and institutions: A co-creation story of the king crab industry. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, Mats, and Jorgen Sandberg. 2011. Generating research questions through problematization. Academy of Management Review 36: 247–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ardichvili, Alexander, Richard Cardozo, and Sourav Ray. 2003. A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing 18: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2014. Promises, premises... An alternative view on the effects of the Shane and Venkataraman 2000 AMR Note. Journal of Management Inquiry 23: 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arend, Richard J. 2015. Mobuis’ Edge: Infinite Regress in the Resource-Based and Dynamic Capabilities View. Strategic Organization 13: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2016. Entrepreneurs as sophisticated iconoclasts: Rational rule-breaking in an experimental game. Journal of Small Business Management 54: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, Richard J. 2018. Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Replications, Applied External Theories and Accumulated Knowledge. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 10: e00098. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, Richard J., Hessam Sarooghi, and Andrew Burkemper. 2015. Effectuation as ineffectual? Applying the 3E theory-assessment framework to a proposed new theory of entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review 40: 630–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arend, Richard J., Hessam Sarooghi, and Andrew C. Burkemper. 2016. Effectuation, not being pragmatic or process theorizing, remains ineffectual: Responding to the commentaries. Academy of management Review 41: 549–56. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, Chris. 1976. Single-loop and double-loop models in research on decision making. Administrative Science Quarterly 21: 363–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacharach, S. B. 1989. Organizational theories: Some criteria for evaluation. Academy of Management Review 14: 496–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, James M. 1906. Mental Development in the Child and the Race: Methods and Processes. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bijker, Wiebe E. 1987. The Social Construction of Bakelite: Toward a Theory of Invention. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 159–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, Barbara. 1988. Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review 13: 442–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxenbaum, Eva, and Linda Rouleau. 2011. New knowledge products as bricolage: Metaphors and scripts in organizational theory. Academy of Management Review 36: 272–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bradie, Michael. 1990. The Evolution of Scientific Lineages. PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association 2: 245–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branthwaite, A. 1975. Subjective value of information. British Journal of Psychology 66: 275–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, James M., and Viktor J. Vanberg. 1991. The market as a creative process. Economics & Philosophy 7: 167–86. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Deborah L., and Philip H. Winne. 1995. Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of Educational Research 65: 245–81. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D. T. 1974. Evolutionary epistemology. In The Philosophy of Karl Popper. Edited by P. A. Schilpp. La Salle: Open Court, vol. 14, pp. 413–63. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, Mark C. 2000. An entrepreneurial theory of the firm. In Competence, Governance and Entrepreneurship: Advances in Economic Strategy Research. Edited by N. J. Foss and V. Mahnke. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiasson, Mike, and Chad Saunders. 2005. Reconciling diverse approaches to opportunity research using the structuration theory. Journal of Business Venturing 20: 747–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiles, Todd H., Allen C. Bluedorn, and Vishal K. Gupta. 2007. Beyond creative destruction and entrepreneurial discovery: A radical Austrian approach to entrepreneurship. Organization Studies 28: 467–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Young B. 1993. Paradigms and Conventions: Uncertainty, Decision Making and Entrepreneurship. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Gilbert. 2003. The disruption opportunity. MIT Sloan Management Review 44: 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, Andrew C. 2005. Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 4: 473–91. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, Per. 2003. The Domain of Entrepreneurship Research: Some Suggestions. In Cognitive Approaches to Entrepreneurship Research (Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, Vol. 6). Edited by J. A. Katz and D. A. Shepherd. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 315–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, Richard. 1976. The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denrell, Jerker, Christina Fang, and Sidney G. Winter. 2003. The economics of strategic opportunity. Strategic Management Journal 24: 977–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubin, Robert. 1969. Theory Building. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, Jeffrey H., and Harbir Singh. 1998. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review 23: 660–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, Linda, and Helena Yli-Renko. 2010. The impact of environment and entrepreneurial perceptions on venture-creation efforts: Bridging the discovery and creation views of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 34: 833–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenzweig, Anton. 1967. The Hidden Order of Art: A Study in the Psychology of Artistic Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review 14: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Denise E. 2006. Entrepreneurial processes and the social construction of opportunity. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 18: 421–40. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Nicolai J., and Peter G. Klein. 2005. Entrepreneurship and the economic theory of the firm: Any gains from trade? In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research: Disciplinary Perspectives. Edited by R. Agarwal, S. A. Alvarez and O. Sorenson. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Nicolai J., Peter G. Klein, Yasemin Y. Kor, and Joseph T. Mahoney. 2008. Entrepreneurship, subjectivism, and the resource-based view: Toward a new synthesis. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2: 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Yiannis. 2010. Organization studies: A space for ideas, identities and agonies. Organization Studies 31: 757–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garud, Raghu, Joel Gehman, and Antonio Paco Giuliani. 2014. Contextualizing entrepreneurial innovation: A narrative perspective. Research Policy 43: 1177–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, Gerd, and Wolfgang Gaissmaier. 2011. Heuristic decision making. Annual Review of Psychology 62: 451–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gioia, Dennis A., and Evelyn Pitre. 1990. Multiparadigm perspectives on theory building. Academy of Management Review 15: 584–602. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, James. 1987. Chaos: Making a New Science. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman, Heather A., Joseph T. Mahoney, and E. Mannix. 2019. Editors’ comments: The role of theory in management research. Academy of Management Review 44: 241–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, Keith M., and Andrew C. Corbett. 2003. Improvisation as a Framework for Investigating Entrepreneurial Action. In Academy of Management Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management, pp. F1–F6. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, Keith M., and R. A. Baron. 2008. Regulatory focus and new venture performance: A study of entrepreneurial opportunity exploitation under conditions of risk versus uncertainty. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2: 285–99. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Alan, and Anthony O’Hear. 1984. On what makes an epistemology evolutionary. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 58: 177–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorens, Vera, Nicole Remmers, and Kemieke Van De Riet. 1999. Time is an amazingly variable amount of money: Endowment and ownership effects in the subjective value of working time. Journal of Economic Psychology 20: 383–405. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Chihmao, Jackson A. Nickerson, and Todd R. Zenger. 2007. Opportunity discovery, problem solving and a theory of the entrepreneurial firm. Journal of Management Studies 44: 1255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, George P. 1991. Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organization Science 2: 88–115. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley, Thomas Henry. 1880. On the application of the laws of evolution to the arrangement of the Vertebrata and more particularly of the Mammalia. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1880: 649–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky, eds. 1982. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. Chan, and Renée Mauborgne. 2004. Blue Ocean Strategy. Harvard Business Review 82: 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, Israel M. 1985. Discovery and the Capitalist Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, Israel M. 1989. Discovery, Capitalism, and Distributive Justice. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Peter G. 2008. Opportunity discovery, entrepreneurial action, and economic organization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2: 175–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Frank H. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. New York: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, Norris F. 2000. The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 24: 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, Norris F. 2003. The cognitive psychology of entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research. Edited by Z. J. Acs and D. B. Audretsch. Greer: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, Thomas S. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, Dennis V. 1956. On a measure of the information provided by an experiment. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 27: 986–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlechild, Stephen C. 1979. Comment: Radical Subjectivism or Radical Subversion. In Time, Uncertainty and Disequilibrium: Exploration of Austrian Themes. Edited by Mario Rizzo. Lexington: Lexington Books, pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, Edwin A. 2007. The case for inductive theory building. Journal of Management 33: 867–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGrath, Rita Gunther, and Ian C. MacMillan. 2000. The Entrepreneurial Mindset: Strategies for Continuously Creating Opportunity in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey, Bill. 1997. Quasi-natural organization science. Organization Science 8: 352–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMullen, Jeffery S., and Dean A. Shepherd. 2006. Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review 31: 132–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohr, Lawrence. 1982. Explaining Organizational Behavior. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, William D., and David Popp. 1997. What is the value of scientific knowledge? An application to global warming using the PRICE model. The Energy Journal 18: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Noteboom, Bart. 2000. Learning and Innovation in Organizations and Economies. New York: Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, Edith. 1959. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pentland, Brian T. 1999. Building process theory with narrative: From description to explanation. Academy of Management Review 24: 711–24. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, Richard L., and John E. Butler. 2001. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Academy of Management Review 26: 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Quine, W. V. 1969. Ontological Relativity. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir, Priya. 2006. An information processing review of the subjective value of money and prices. Journal of Business Research 59: 1053–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoglou, Stratos, and Eric W. Tsang. 2017. In defense of common sense in entrepreneurship theory: Beyond philosophical extremities and linguistic abuses. Academy of Management Review 42: 736–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof, K. Richard, Wery P. Van Den Wildenberg, Sidney J. Segalowitz, and Cameron S. Carter. 2004. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: The role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain and Cognition 56: 129–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rindova, Violina P., and Suresh Kotha. 2001. Continuous “Morphing” competing through dynamic capabilities, form, and function. Academy of Management Journal 44: 1263–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rowbottom, Darrell P. 2010. Evolutionary epistemology and the aim of science. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 88: 209–25. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Filipe M., and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt. 2004. Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries: Entrepreneurial Action in Nascent Fields. Academy of Management Best Papers Proceedings. Briarcliff Manor: Academy of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, Yolanda, Thomas Dean, and Jesse F. Dillard. 2006. Entrepreneurship as the nexus of individual and opportunity: A structuration view. Journal of Business Venturing 21: 286–305. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasvathy, Saras D. 2001. Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review 26: 243–63. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest and the Business Cycle. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1939. Business Cycles. A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, Scott, and S. Venkataraman. 2000. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review 25: 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, Vernon L. 1962. An experimental study of competitive market behavior. Journal of Political Economy 70: 111–37. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, Roy. 2010. Editor’s comments: Construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Academy of Management Review 35: 346–57. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, Roy, C. Hardy, and Quy Huy Nguyen. 2011. Introduction to special topic forum: Where are the new theories of organization? Academy of Management Review 36: 236–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Robert I., and Barry M. Staw. 1995. What theory is not. Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 371–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sweezy, Alan R. 1934. The interpretation of subjective value theory in the writings of the Austrian economists. The Review of Economic Studies 1: 176–85. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, David J. 1986. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy 15: 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Kanneth W., and Walter. G. Tymon. 1982. Necessary properties of relevant research: Lessons from recent criticisms of the organizational sciences. Academy of Management Review 7: 345–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, Eric W., and Florian Ellsaesser. 2011. How contrastive explanation facilitates theory building. Academy of Management Review 36: 404–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1974. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 185: 1124–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghely, Ivan P., and Pierre-André Julien. 2010. Are opportunities recognized or constructed? An information perspective on entrepreneurial opportunity identification. Journal of Business Venturing 25: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, Sankaran. 1997. The distincitive domain of entrepreneurship research: An editor’s perspective. In Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence, and Growth. Edited by J. Katz and R. Brockhaus. Greenwich: JAI Press, vol. 3, pp. 119–38. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl E. 1979. The Social Psychology of Organizing. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Welter, Chris, and Sharon Alvarez. 2015. The state of opportunities: Clarifying the transitions between opportunity types. Management Decision 53: 1398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetten, David A. 1989. What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review 14: 490–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiseman, Jack. 1989. Cost, Choice, and Political Economy. Aldershot: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Matthew S., and William McKinley. 2010. The production of entrepreneurial opportunity: A constructivist perspective. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 4: 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., Harry J. Sapienza, and Per Davidsson. 2006. Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies 43: 917–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Stage | Criteria | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Experience | Built upon the existing literature |

|

| Built on valid observation |

| |

| Explain | Units:

|

|

| Clear laws (about unit interaction) |

| |

| Boundaries specified: precise rules |

| |

| System states exist |

| |

| Propositions consistent with model |

| |

| Reasonable assumptions |

| |

Logic:

|

| |

| Establish | Empirically testable |

|

| Diffused in the literature |

| |

Practitioner value:

|

|

| Benchmark (Idealized) Theory | Comparison-Based Theorizing | |

|---|---|---|

| Value |

|

|

| Concerns |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arend, R.J. Entrepreneurship’s Creation School and Its Comparison-Based Approach: Assessing the Lessons for Theory’s Progression. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080181

Arend RJ. Entrepreneurship’s Creation School and Its Comparison-Based Approach: Assessing the Lessons for Theory’s Progression. Administrative Sciences. 2023; 13(8):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080181

Chicago/Turabian StyleArend, Richard J. 2023. "Entrepreneurship’s Creation School and Its Comparison-Based Approach: Assessing the Lessons for Theory’s Progression" Administrative Sciences 13, no. 8: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080181

APA StyleArend, R. J. (2023). Entrepreneurship’s Creation School and Its Comparison-Based Approach: Assessing the Lessons for Theory’s Progression. Administrative Sciences, 13(8), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13080181