Abstract

This research investigates the intricacies of motivation and job satisfaction among military service members within the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) amidst various challenges. Employing an intrinsic–extrinsic framework, the study adopts a sequential mixed-method design. Interviews were conducted with 42 LAF service members, a Focus Group was convened with 12 LAF subject matter experts, and a survey was administered to 3880 LAF service members across the country. The findings underscore the significance of monetary rewards and praise as primary motivators. Notably, the expectation of rewards emerges as a crucial motivating factor closely linked to job satisfaction, while intrinsic factors exhibit comparatively lesser influence. Salary emerges as the foremost determinant of job satisfaction. Moreover, economic challenges, particularly the drastic decline in purchasing power, serve as a significant moderating factor, adversely impacting the relationship between motivation and job satisfaction. Health challenges, such as the scarcity and increased prices of medical supplies, also exert a negative moderating influence. Conversely, security challenges demonstrate no significant moderating impact. Insights gleaned from the Lebanese context emphasize the importance of offering competitive salaries and recognition programs, ensuring equitable compensation, designing reward systems aligned with performance expectations, regularly reviewing, and adjusting salary structures, providing comprehensive support for employees’ physical and mental well-being, and fostering a secure work environment.

1. Introduction

Human Resource Management (HRM) is of utmost importance in organizations across various sectors, including business, government, nonprofit, and the military (Rastogi 2002). Organizations are nowadays increasingly emphasizing HRM and investing in their human capital to overcome faced challenges and achieve organizational success (Arena and Uhl-Bien 2016). For as long as people have been considered crucial for any organization’s growth, theorists and practitioners have wrestled with studying their motivation and job satisfaction (Holbeche 1998). The level of professionalism of any organization depends on implemented strategies regarding the motivation and job satisfaction of its workforce (Matar 2015). Studies show that only 19% of employees are highly motivated (Guta 2020), and only 20% of workers are passionate about their jobs (Flynn 2022). While challenges are issues, risks, or threats that necessitate physical or mental effort; they require organizations to handle them and take advantage of opportunities (Starik and Marcus 2000).

Military service is unlike any other job, with unique characteristics governing its activities such as assigned missions, completed tasks, or working conditions, among others (Nuciari 2018). Military organizations are generally perceived as sometimes the ultimate and only nation builders especially in highly segmented and heterogenous societies (Bahout 2014). In such conditions, the relationships between motivation and job satisfaction of individuals in military organizations in the context of faced challenges reveal complex dynamics governing service members’ perceptions. These tenets depend on both a person’s external context (culture, society, mission, task, etc.) and internal characteristics (perceptions, feelings, attitudes, etc.) (Kerlinger 1979). A comprehensive review of related theories and their application in the military provides a better understanding of the various factors that influence individuals’ behavior and represents excellent research opportunities and great relevance for many cases across the globe.

In this context, the problem of motivating individuals to increase their job satisfaction becomes increasingly significant. Although this problem has received much attention in the business world, it still requires further investigations in the domain of the armed forces (Barak 2009). Regardless of personal preferences, one point seems clear these variables are interrelated, associated, and cannot be studied separately. Formulated in an extrinsic-intrinsic framework, this article topic is relevant for many cases across the globe that involve Human Resources (HR) considering the downward slide of conditions and the deterioration of the currency to offer a better understanding of the motivation and job satisfaction concepts in the overlooked military setting in an organizational context.

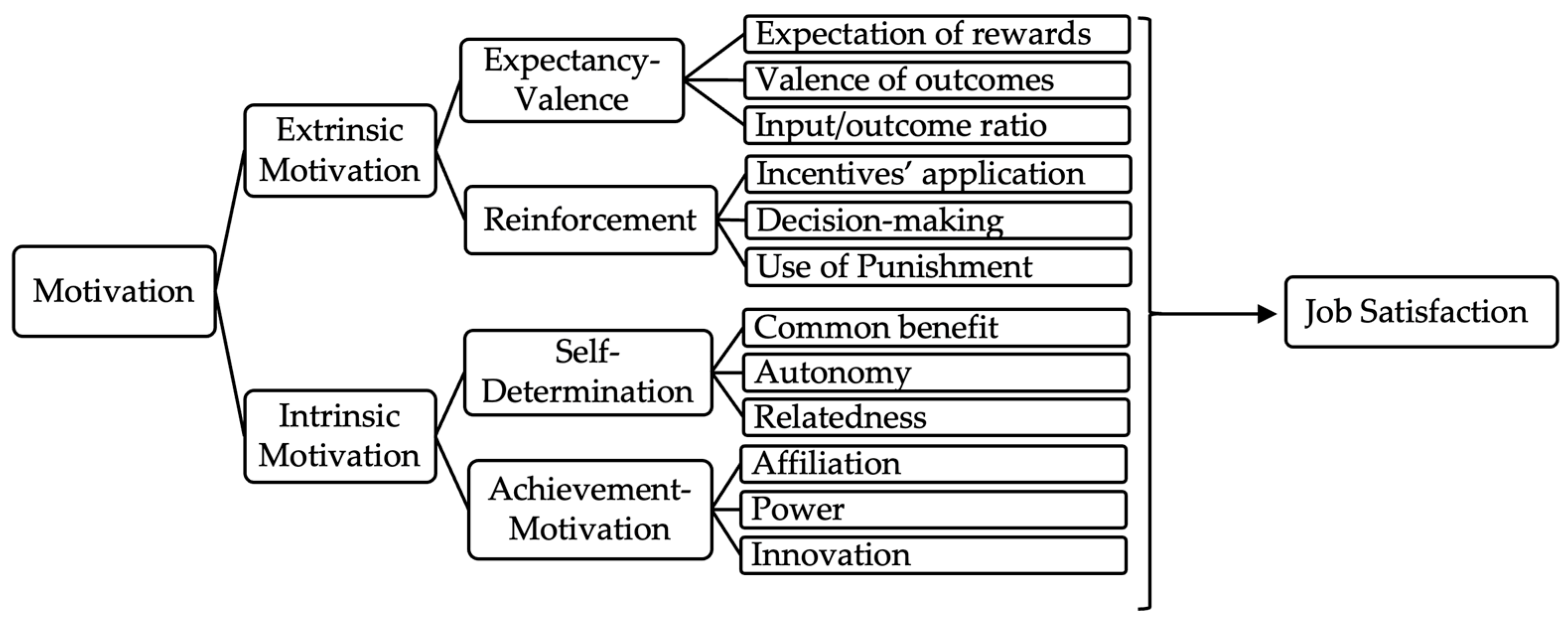

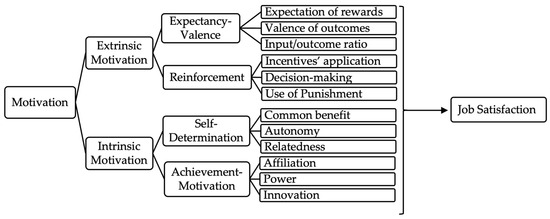

First, the article introduces a novel research design by incorporating new antecedents of motivation in line with the popular extrinsic–intrinsic framework precisely extrinsic factors using Expectancy–Valence and Reinforcement theories, and intrinsic factors using Self-Determination and Achievement–Motivation theories. This represents novel models that define the role of these factors in the military setting, thus building a novel theory to explain how or why this relationship exists by expanding previous studies and theoretical perspectives examining motivating individuals in public organizations. Additionally, another contribution is the renowned theories of job satisfaction specifically the Equity and the Motivator–Hygiene theories at the individual level, which helped better conceptualize the underpinning issues of job satisfaction and its factors’ role in the military setting and revealed the significance of employing these two theories and how they are beneficial in explaining the relationship in the context of armed forces. In addition, by examining the causal relationships between motivation and job satisfaction and capturing data over a specific time in an empirical exploration, the manuscript provides stronger evidence for causal claims and contributes to the understanding of the dynamic nature of motivation and job satisfaction. Furthermore, by exploring the moderating effect of challenges that influence the relationship between motivation and job satisfaction, the manuscript contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms through which motivation affects job satisfaction or how the relationship varies under different conditions.

The researcher’s effort to develop a conceptual theoretical model and integrate a relevant, reliable, and valid tool to measure the challenges along the economic, health, and security in a new form of specificity in the military as an additional variable in the camp of discussions, the research contributes to extending the existing literature concerning faced challenges and related outcomes. Lastly, the manuscript offers opportunities for conducting a comparative analysis of motivation and job satisfaction across different cultural or contextual settings. This can involve studying how these constructs manifest and operate in diverse organizational or cultural contexts building on the Lebanese case, leading to a deeper understanding of their aspects.

Developing adequate multifaceted strategies through enhancing service members’ motivation and overcoming the challenges they are facing and those that may lie ahead, offers significant and lasting improvements in their job satisfaction and enables military organizations to successfully conduct their missions and tasks. Even though this relationship seems to prevail as a critical approach for organizations’ efficiency and effectiveness, the focus on the LAF has not been a major part of enhancing their activities.

The LAF has unique organizational characteristics shaped by Lebanon’s history, confessional system, and struggles. These characteristics create a force designed for national unity, internal stability, and operating in challenging terrain. However, it comes with trade-offs in terms of efficiency, advanced capabilities, and responsiveness to large-scale external threats.

The primary mission of the LAF is to defend Lebanon against external aggression, maintain internal stability, and support the government in times of crisis. Following the Lebanese Civil War, the Lebanese government entrusted the LAF with the mission of keeping peace and stability in the country’s interior, together with the other security forces which includes counter-terrorism operations and disaster response (Directorate of Orientation 2021). Since then, the LAF has increasingly focused on internal security and counterterrorism alongside traditional border defense duties. The LAF is currently deployed across all the Lebanese territories, with units assigned to each of the five military regions that cover the nation’s geography. This fosters local connections but might limit a unified response to nationwide threats. Due to this focus on internal security, the LAF is primarily a light infantry force with Mechanized Infantry Brigades, Intervention Regiments, Special Units, and Specialized Units. This makes the troops adaptable but limits capabilities in large-scale conventional warfare.

The 2019 Lebanon’s economic struggles and financial collapse negatively impacted the LAF’s budget, limiting access to advanced weaponry and technology. Therefore, the LAF currently relies on international military aid from countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, among others. Without their support and assistance, the LAF would not have been able to successfully defend national security and stability. This support has been crucial in increasing LAF’s capacity, improving its operational effectiveness, and strengthening its resilience in the face of impending threats and challenges.

In this context, investigating the intricacies of motivation and job satisfaction among LAF service members is extremely important. Moreover, a forward-thinking strategy that emphasizes enhancing the LAF’s capacity to adapt to intricate and varied difficulties is necessary to meet the new strategic and operational challenges arising from such a dynamic environment.

Lebanon has experienced a complex history marked by political instability, conflict, and external pressures, which have undoubtedly influenced the motivation and job satisfaction of its armed forces. The LAF has faced significant challenges due to the country’s history of internal conflicts and external threats (Dagher 2017). These challenges have created a distinct military context that requires an understanding of the specific dynamics and factors affecting motivation and job satisfaction among service members. The LAF has been actively engaged in maintaining internal security, combating terrorism, and contributing to peacekeeping missions (Nerguizian and Cordesman 2009). The nature of these operations can impact the motivation and job satisfaction of military personnel. Understanding how service members perceive and respond to these operational demands is crucial for enhancing their motivation and job satisfaction. The LAF organizational culture in Lebanon, shaped by its history, values, and traditions, plays a role in influencing motivation and job satisfaction (Kilcullen 2022). Exploring the cultural aspects of the military in Lebanon can provide insights into how these factors impact service members’ well-being and effectiveness. The LAF operates in a complex socio-political environment, affected by regional dynamics and external pressures (Dagher 2018b). Understanding how external factors, such as geopolitical considerations, influence motivation and job satisfaction in the armed forces can help develop strategies to address challenges and promote positive outcomes. By conducting research and studying the motivation and job satisfaction of the LAF, scholars, and practitioners can gain valuable insights that may have broader implications. While each military context is unique, the findings from a case study like Lebanon can contribute to the general understanding of motivation and job satisfaction in the armed forces globally. They can help identify common factors, challenges, and potential strategies that can be applied or adapted to other military contexts. Therefore, the Lebanese case has a lot to offer for making sense of, and further taking advantage of, the motivation and job satisfaction angle in many cases across the world allowing a positive effect on the generalizability of the findings to other regions of the world.

In recent years, Lebanon has undergone an unprecedented crisis displayed by economic, social, security, political, and later health challenges (World Bank 2021). The Lebanese currency, by mid-March 2023, has lost more than 93% of its value versus the US dollar in the black-market (Bloomberg 2023). The monthly inflation rate reached around 190% in February 2023 (Trading Economics 2023). Poverty, starvation, and destitution caused by the skyrocketing unemployment rate endangered thousands of Lebanese families and led to social instability and tensions (HawkSight et al. 2021). Moreover, the country faces different security issues, from many immigrants and refugees to the camps’ safe havens for terrorists, and the country’s external threats (Chehayeb 2021). Furthermore, the de facto Sectarian system’s religious and political tensions crippled the cabinet and impeded electing of a new president and producing a new government (Badaan et al. 2020). Moreover, the lift of medical supply subsidies in 2022 led to the continued decline of the Lebanese health system, threatening this key retention asset (Isma’eel et al. 2021).

The LAF, as part of the Lebanese Ministry of National Defense (MOD), faces this unprecedented crisis manifested by a lack of resources and recent reductions in the LAF budget allocation (Cortés and Kéchichian 2021). The LAF service members face a drastic decline in the value of their salary causing a deteriorated purchasing power to more than 95%, plunging them into unprecedented poverty (Sabaghi 2022). Increasing reports in the last few years exposed a decline in the levels of the LAF service members’ satisfaction in service coupled with increased moonlighting, Absenteeism without Official Leave (AWOL) rates, and instances of dereliction of duty (Saab 2021). Moreover, the military health care system as part of the Lebanese health sector, which covers more than 400,000 active-duty, retirees, and direct families, is facing shortages of medicines and drugs, medical supplies, and doctors and nurses (Isma’eel et al. 2021). With the continuous decline in the economic situation, the LAF service members’ satisfaction in service members may continue to decline (Schenker and Rumley 2021).

With the context of these specific challenges, understanding these relationship properties on both the organizational and individual levels can help define better ways to motivate the LAF service members to increase their job satisfaction which emerges as a major problem to be addressed (Hoffman 2019). Even though these challenges did not verbally highlight reassessing the job satisfaction of the LAF service members, they revealed the need to develop a sustainable, suitable, and cost-effective approach mainly in HR and design more efficient structures to optimize its employment of the available means (Faris 2019). Any understanding of these structures should rely on primary sources of information from various feedback, opinions, and perceptions of the LAF service members (Greenhalgh and Peacock 2005). Unpacking the true meaning and real image of these acquired sets of attributes helps cover most aspects of the research problem and frame a solution in a comprehensive approach, as well as accounting for the myriad variables in the complex problem (Ahmad 2009).

The primary inquiry guiding this research is centered on understanding how the challenges confronting service members can influence the interplay between motivation and job satisfaction. To delve deeper into this overarching question, the study poses several sub-questions:

What are the key motivators, job satisfaction determinants, and challenges faced by military personnel in the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF)?

Which specific motivational factors contribute most significantly to the job satisfaction of LAF service members?

How do these encountered challenges affect the overall job satisfaction levels among LAF personnel?

To address these queries comprehensively, the research contextualizes the backdrop of motivation and job satisfaction within the sphere of encountered challenges. Subsequently, it gathers insights from LAF service members through a variety of methods, including interviews, focus groups, and surveys. Through an analysis of the gathered data, the paper delineates the primary challenges faced by LAF service members and their implications on job satisfaction, identifies key motivators, and determinants of job satisfaction, explores the intricate relationship between motivation and job satisfaction, and examines the moderating influence of encountered challenges. Drawing lessons from the experiences of the LAF and linking them to broader knowledge development, the research also offers insights for both academics and practitioners, aiming to deepen their understanding of how challenges can shape the dynamics between motivation processes and job satisfaction outcomes.

2. Theoretical Background Motivation and Job Satisfaction

Almost every firm in the world relies on human resource management to design employee-supportive policies and initiatives. This is because personnel are an organization’s most valuable asset. Motivating them is an important aspect of this plan because it is directly related to their efficiency and effectiveness. Furthermore, enhancing job happiness is critical for improved performance and productivity (Markel et al. 2011). The overall body of literature demonstrates continuity between military-oriented and non-military institutions, with certain distinctions for the military (Kwasniewski 2020).

In the armed forces, the importance of motivating personnel seems more important compared to civilians due to the unique nature of military service, which often involves high-risk situations, demanding physical and mental challenges, and long periods of separation from family and loved ones. Motivated personnel are more likely to perform their duties effectively and efficiently, even in adverse conditions (Brœnder and Andersen 2014). Motivation represents the persistent desire, assessed in psychological processes that drive an individual’s arousal, direction, decision, commitment, and perseverance to conduct certain activities (Migueles and Zanini 2018). In public organizations, Andersen et al. (2013) suggest a unique context for motivating individuals designated as Public Service Motivation (PSM) that Perry and Wise (1990) defined as the motives grounded primarily in public institutions. Brewer and Selden (1998) describe PSM as the motivational force to perform meaningful public service. Rodrigues-Goulart (2006) assumes that motivation is crucial to leading military personnel, and in most cases, the key to achieving success in combat. While extrinsic factors are external aspects that people strive for (Sansone and Harackiewicz 2000), intrinsic factors represent the deepest aspects that inspire individuals (Taillard and Giscoppa 2013).

Moreover, having service satisfaction is of a great deal in the military compared to the civilian sector. Military service involves a high level of commitment, sacrifice, and dedication. Therefore, ensuring that service members have a satisfactory experience and are content with their roles is crucial for the overall functioning and morale of the armed forces (Fredland and Little 1983). Job satisfaction represents a frequently used metric of workplace well-being that has gained significant academic attention (Aoun et al. 2021). While intrinsic job satisfaction relates to the amount to which workers feel favorably about the duties themselves (e.g., completion, recognition, etc.), extrinsic job satisfaction refers to the work environment (e.g., salary, supervision, relations, etc.) (Spector 1997). Schaffer (1953) states that the larger the relative intensity of the need on which emotions of satisfaction rely, the stronger the association between job satisfaction and need fulfillment is (Rafferty and Griffin 2009). Herzberg et al. (1959) establish two groups of elements, Hygienes and Motivators, that impact work attitudes and job satisfaction. Work satisfaction and dissatisfaction reflect a person’s contentment, happiness, and fulfillment or discontent, unhappiness, and frustration with distinct job characteristics (Armstrong 1996). In organizational research, and as defined by Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), job satisfaction is the pleasant emotional state resulting from job experiences that have cognitive, affective, and behavioral components (Bandura 1999). Dawis and Lofquist (1991) explain that these sensations rely on how well their requirements match their surroundings.

Most of the existing debates in literature dealing with the interrelations of these parameters found that job satisfaction is directly tied to those factors that influence people’s motivation (Österberg and Rydstedt 2018). Rogers and Prentice-Dunn (1997) state in their Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) that challenges directly impact individuals’ behaviors, risk perceptions, and risk tolerance in response to these challenges and accordingly their efficiency and effectiveness. According to Jayakumar et al. (2009) and Varma (2017), employees’ motivation and job satisfaction affect their ability to overcome business issues. Ohly and Fritz (2010) assert that low wages, difficult settings, and time pressure demotivate employees. Singh and Tiwari (2011) claim that a lack of motivation and job satisfaction is one of the biggest issues facing organizations today. Phiphadkusolkul (2012) emphasizes extrinsic motivation causes sorrow when mishandled, whereas intrinsic motivation brings joy when problems are overcome. Widmer et al. (2012) assert that workload and demanding jobs are stressful and drain energy. Okafor (2014) states that the Nigerian civil service’s motivation and work satisfaction issues are incomplete without evaluating its policies and procedures. Tadić Vujčić et al. (2017) emphasize the job’s passion and stress the importance of motivating people to face difficulties. Saragih et al. (2020) suggest that driven, self-confident, and loyal employees can conquer any challenge. Botchwey and Ahenkan (2021) explain that economic resources should motivate nurses by providing logistical supplies, safe working environments, and the possibility to express their thoughts. Rashmi (2021) states that training, performance management, career progression, and cash incentives motivate and satisfy employees. Grigorov (2020) highlights the increasing difficulty faced by armed forces worldwide in recruiting and retaining qualified personnel emphasizing the importance of understanding the factors that influence motivation and job satisfaction to address these challenges effectively. Barrick et al. (2001) explain that highly motivated and satisfied personnel tend to perform better and exhibit a greater commitment to their duties, leading to improved operational effectiveness and mission success. Bryant and Veroff (2017) state that job satisfaction plays a vital role in promoting mental health and reducing suicide risk among military personnel. Exploring the connection between job satisfaction, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide risk highlights the importance of addressing job satisfaction to enhance overall well-being in the armed forces. Huaman et al. (2023) argue that job satisfaction also mitigates the negative effects of stressors on military personnel. Understanding how job satisfaction influences resilience and overall well-being contributes to developing strategies to support personnel in challenging environments. Rawashdeh and Tamimi (2020) assert that exploring intrinsic motivation, extrinsic rewards, and job characteristics helps identify key drivers of job satisfaction and performance in the armed forces. Investigating the relationship between job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover intentions among military personnel offers valuable insights into fostering commitment and reducing turnover rates. Penconek et al. (2021) state that examining variables such as leadership, job characteristics, organizational climate, and social support reveals their relationship with job satisfaction in specific military occupational specialties, providing targeted insights for improvement. Nderitu (2013) shows that financial incentives showed a significant, strong, and positive regression (R2 = 0.881) with job satisfaction among 520 respondents in Government departments in Kenya. Catharina and Victoria (2015) proclaim that extrinsic motivation indicators (Hygienes) showed the most significance with a Standardized Coefficient β = 0.321 followed by the intrinsic factor (Motivators) with β = 0.522 in a study on 103 employees in the finance service department in Indonesia. Mafini and Dlodlo (2014) reveal statistically significant and positive relationships (0.179 ≤ r ≤ 0.643) between the extrinsic motivation factors of remuneration, quality of work life, supervision, promotion, and teamwork, accounting for approximately 56% (R2 = 0.558) of the variance of job satisfaction among 246 respondents in a South African public organization. Al Tayyar (2014) describes a significant relationship between satisfaction and general motivation (r = 0.60), a relatively strong one between satisfaction and extrinsic motivation (r = 0.45), and a less strong one between satisfaction and intrinsic motivation (r = 0.39) were identified in a study on 737 teachers in 24 schools in Saudi Arabia. The research on 128 participants in the banking sector in Iraq, reveals that rewards, compensations, and incentives have the most significant and positive correlations (0.499 > r > 0.611) with high regression (0.687 > R2 > 0.764) on job satisfaction (Ali and Anwar 2021). Challenges have a great impact on individuals’ perceptions of motivation whose most significant factors that impact job satisfaction are extrinsic factors of salary, work conditions, financial benefits, and monetary incentives, followed by intrinsic factors such as empowerment, learning, and promotion (Aoun et al. 2021). The observed studies in the LAF only touch areas surrounding the topic under investigation. Haydar (2016) recommended restructuring its HRM institutions to reduce bureaucracy and optimize HR practices. Abdel Wahab (2015) studies how raising the moral spirit of the LAF service members assists in combat to attain victory. Abdel Sater (2015) and Dagher (2018a) examine processes to increase professionalism at the institutional level which would raise the performance of the LAF in facing the challenges in its OE. These diverse research studies collectively contribute to the understanding of motivation and job satisfaction in armed forces, offering valuable guidance for researchers, policymakers, and military organizations seeking to gain insights on the development of strategies and interventions aimed at effectively addressing these factors by military organizations.

To better understand and address these dynamics, many militaries have conducted investigations, studies, and inquiries aiming to examine the factors that contribute to motivation and satisfaction among service members. By understanding these factors, militaries can develop strategies and implement programs that promote the effectiveness and efficiency of their armed forces. This knowledge helps them create an environment that supports the well-being, motivation, and job satisfaction of their personnel, ultimately enhancing the overall operational readiness and success of the military organization. However, despite the increasing recognition of the motivation and job satisfaction importance, to fully harness their potential, they still require more attention from both scholars and practitioners. This includes the need for more research on the effectiveness and impact of motivation and job satisfaction in different contexts, as well as the development of best practices and guidelines considering faced challenges. Different military contexts may present unique challenges and circumstances that influence motivation and job satisfaction (Valor-Segura et al. 2020). Factors such as the nature of military operations, organizational culture, deployment conditions, and leadership styles can significantly impact service members’ motivation and job satisfaction. It is essential to conduct research that considers these contextual factors to develop a more nuanced understanding and tailored strategies. There are unique challenges faced in the military context that can hinder motivation and job satisfaction (Österberg et al. 2017). These challenges may include prolonged deployments, high-stress environments, limited resources, and difficulties in maintaining work–life balance. Further attention is needed to identify these challenges and develop strategies to mitigate their impact on motivation and job satisfaction. This may involve improving support systems, providing training and development opportunities, enhancing communication channels, and fostering a positive and inclusive work environment. By dedicating more attention to these areas, scholars and practitioners can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of motivation and job satisfaction in the military. This knowledge can lead to the development of evidence-based practices and policies that promote the well-being and effectiveness of military personnel, ultimately benefiting the armed forces.

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Focus

The research aims to examine the interdisciplinary aspects of motivation and job satisfaction considering the current challenges that the LAF service members are facing. The study draws on literature from the fields of civilian aiming to contribute to theory in the armed forces field and HR development. The most related motivation theories to the ongoing investigation were categorized into Content-Based theories and Process-Based theories. The most convenient content-based theories are McClelland’s (1987) Achievement-Motivation Theory (AMT) and McGregor’s (1960) Theory X and Y. The most suitable process-based theories are Vroom’s (1964) Expectancy-Valence Theory (EVT), Deci and Ryan’s (1985) Self-Determination Theory (SDT), and Skinner’s (1974) Reinforcement Theory (RT). The most inspiring job satisfaction theories applied in this research as the theoretical frameworks are those of Adams’s (1963, 1965) Equity Theory and Herzberg et al.’s (1959) Motivator-Hygiene Theory. The researcher considered these theories to have crucially influenced thoughts on motivation and job satisfaction and to be the most pertinent in the military setting and the research extrinsic–intrinsic framework.

The research provides much-needed insights into the approaches to, driving forces behind, and attitudes towards motivation, job satisfaction, and reactions to challenges. Specifically, it aims to:

- Explore the most significant factors of motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges of military personnel.

- Inspect the specific relationships between motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges.

- Bridge the gap between theory and practice on motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges.

3.2. Research Setting

The LAF is mainly comprised of the LAF Command, the Land Forces, the Air Forces, the Navy Forces, and the Military Academies and Schools (Lebanese University: Center for Research and Studies in Legal Informatics 1981; Ministry of National Defense 1983; Dagher 2018b). The LAF size has changed according to the historical periods, the war-peace situation in the country, and the assigned missions and required tasks. Before the economic crisis in 2019, the LAF size was around 84,000 (Saab 2019). At the beginning of 2023 (the date of the data collection), the LAF total force decreased to nearly 81,000 due to the increased desertions and AWOL among its ranks (Directorate of Orientation 2021). The main study included, although 97 were contacted originally, 85 units in the MOD and the LAF as shown in Table 1 below. These participating units were arranged into two sub-groups, namely the Non-Operational Units with a total of 56 units, and the Operational Units which totaled 29 units. They represent all the geographic regions in Lebanon and allow us to explore service members’ perceptions of different cultural and societal traits.

Table 1.

List of participating units.

3.3. Research Method

Within the research extrinsic–intrinsic framework, the researcher chose to follow an Exploratory Sequential Mixed Method Design that included both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Bryman and Bell 2011) whose results were used to answer the research questions (Creswell 2014). Implementing both methods aimed to mitigate the weaknesses and limitations of each approach alone and to exploit the strengths of the two forms of data collection (Creswell and Clark 2011). The instruments were piloted with a small set of 96 LAF service members in November 2022 by the researcher using the Simple Random Sampling technique (Olken and Rotem 1986) and adjustments were made accordingly. The used language was Arabic which represents the mother language and formal internal and external mailing dialect of the LAF. All tools were prepared in English then translated into Arabic and written in a simple vocabulary level. The findings were analyzed and then translated back into English for interpretation. The study involved three main data-collection tools: an interview, a focus group, and a survey. 42 LAF service members were interviewed, 12 LAF subject matter experts (SMEs) were gathered in a Focus Group, and 3880 LAF service members were surveyed. In terms of exclusion criteria, the ranks of Major General and General were excluded for their status’ specificity.

First, the on-site interviews were conducted between November and December 2022 through direct engagements with 42 LAF service members. The sample size was determined according to Morse (2000). Permission was granted by the LAF leadership to conduct interviews and the study sites were respective units of participants. The researcher applied the Probability Sampling technique, namely the Simple Random Sampling, in which he randomly selected the interviewees from the LAF different units (Table 2) (Olken and Rotem). These interviews led to the identification of several noteworthy patterns that the researcher incorporated into his analysis (Bryman 2012). While conducting the interviews which lasted between 15 and 20 min (Supplementary Material Table S1), the researcher asked the questions in soldiers’ everyday language and gave them space to evoke unrestricted and non-structured opinions.

Table 2.

Interviewee’ Participants.

After conducting the interviews and withdrawing common themes from the LAF service members’ perspectives, the researcher opted to gather a Focus Group in January 2023 using a Non-Probability Sampling, namely the Purposive Sampling technique (Etikan et al. 2016), in which 12 SMEs were purposively selected from the LAF institutions that were considered most relevant to the research topic (See Table 3 below). The sample size was determined according to Krueger (2014). The inclusion criteria were the expertise, knowledge, and proficiency of SMEs in the research scope. The study site was the LAF HQ in which participants were gathered at a round table and the researcher limited his role to guide the course of the debate. The focus group questions (See Supplementary Material Table S2) aim to reveal the participants’ shared understandings of their specific experiences and perceptions regarding motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges.

Table 3.

Focus Group Participants.

The third data-collection tool was the survey, which was framed along the challenges, motivation, and job satisfaction that constituted its 3 sections (plus demographics) and was conducted in February 2023 (See Supplementary Material Table S3). The survey instruments were the Motivation Beliefs Inventory (MBI) of Facer et al. (2014) which measures leaders’ beliefs about employees’ motivation along four theoretical sub-scales: Self-Determination, Achievement-Motivation, Expectancy-Valence, and Reinforcement, representing each a single motivation theory (Facer et al. 2014); the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) Short-Form of Weiss et al. (1967) which measures satisfaction with several specific aspects of work and its environment (Weiss et al. 1967); a constructed challenges tool based on the Economic, Health, and Security pillars. The rating scale of the three instruments was the five-point Likert-type ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree to allow to conveniently compare results. The Probability Sampling technique, namely the Stratified Random Sampling was applied (Aoyama 1954), in which the population—LAF (N = 81,000 service members) was divided into homogeneous groups (Stratum) namely its three rank categories (4000 Officers (5%); 30,000 NCOs (37%); 47,000 Privates (Including Enlisted) (58%)) to keep their characteristics. The researcher then took a simple random sample from each Stratum to form the sample. Because of the low number of civilian employees and the military scope of the research, they were excluded from the sample. This sampling method is an Equal Probability of Selection Method (EPSEM) because it gives each LAF service member an equal chance of participation (Peters and Eachus 1995). The minimum convenient sample size is n = 384 which the researcher chose to expand around ten times because of the accessibility in reaching the respondents; therefore, “n” became 3880 (Krejcie and Morgan 1970). The questionnaires were distributed using the LAF internal mail system to 97 units representing all geographic regions in Lebanon, which were asked to reproduce and fill 40 questionnaires distributed to 2 Officers, 15 NCOs, and 23 Privates (including Enlisted). As to specific subject selection within each LAF unit, service members were randomly selected by an assigned Officer for this purpose in coordination with his/her leadership. Although none of the soldiers withdrew voluntarily, 3116 questionnaires from 85 respondent units were returned making the response rate high at 80.31%.

The sample demographics (Table 4) show that a very large proportion of the respondents (62.6%) served in Non-Operational Units; an even greater number (86.2%) were male compared to 13.8% of females; more than half (54.2%) were between 21 and 30 years old; an almost equal division between Single and Married (47.5% and 51.2%); almost one-fourth (27.7%) live in Mount Lebanon; more than half (53.5%) were Privates (Including Enlisted); almost half (44.4%) had secondary level of education; more than two-third (68%) earn less than 2,000,000 LL monthly; more than half (58.8%) had less than 11 years of service; a slightly less proportion (40.6%) served less than 6 days a month; almost one-third (32.5%) lived less than 1 h from their homes.

Table 4.

Service members’ demographic characteristics.

All instruments elicited responses on approaches to and experiences with the main motivation factors affecting service members’ job satisfaction in the LAF, attitudes towards the driving forces behind motivation impact on their job satisfaction, and the impact of the faced challenges on the relation between their motivation and job satisfaction.

The overall research aim generated five research questions, which formed the study guide:

- What are the main challenges that LAF service members are facing?

- What are the main motivation factors of the LAF service members?

- What are the main job satisfaction factors of the LAF service members?

- How do the LAF service members’ motivation factors influence their job satisfaction?

- How do faced challenges impact the LAF service members’ job satisfaction?

3.4. Data Analysis

The analysis of the collected data from interviews was conducted using NVivo 10. software to organize, report, and display the results from the sample (Nick 2007). The collected data were subject to thematic analysis using hand coding to systematically develop a general sense of it (Guest et al. 2011). The study did not only seek to get simple yes or no answers; instead, it searched for recurring ideas and common trends from the soldiers’ experiences and perspectives (Browne and Keeley 2007). Although this approach was time-consuming, its analysis reflected collected evidence from participants (Fielding 1993).

The analysis of the collected data from the Focus Group was conducted manually on Microsoft Word and was subject to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2012). The aim is to succinctly uncover participants’ patterns (Nick 2007). This systematic collection of perceptions helps to understand the service members’ shared beliefs (James and Slater 2014).

The answers from the survey were in the form of paper-and-pencil and were captured electronically into Google Forms, exported to Excel, and then analyzed in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26) software. The SPSS descriptive statistics included correlation (Pearson and Unstandardized Coefficient), regression analysis, and moderating analysis (Baron and Kenny 1986). This phase aims to generalize the findings to the research population (LAF) (Polit and Beck 2010).

One of the primary challenges encountered in this research, alongside its inherent limitations, was the dearth of existing research or statistical data within the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) pertaining to the relationships between service members’ motivation, job satisfaction, and their responses to various challenges. Consequently, the researcher opted for an exploratory sequential mixed method approach, enabling the collection of statistical data through diverse avenues to address this gap in the literature effectively. Another constraint arose from the categorization of data and the need to maintain confidentiality, which hindered the researcher from accessing detailed information, restricting them to more generalized data. To offset this limitation, the researcher expanded the survey sample size, encompassing 3880 service members across all 97 LAF units, and endeavored to achieve a high response rate. Furthermore, bureaucratic hurdles within the LAF, common to many military institutions, posed challenges to accessing information. Similarly, the discretion surrounding detailed figures within the LAF influenced the selection of sampling methods in each phase of data collection to ensure the representativeness of each sample vis-à-vis the entire LAF population. Additionally, the study was constrained by time limitations, providing a snapshot of the population’s characteristics at the time of qualitative and quantitative data collection. While this offered a reasonable approximation of the research variables, it did not fully account for the ongoing economic deterioration in the country.

4. Research Findings and Discussion

The aggregated results on service members in the LAF considering faced challenges that will be detailed below are summarized in Table 5 below as follows: The extrinsic factors of Monetary rewards and Praise are the most significant motivating factors. Salary is the most important job satisfaction factor. Expectation of rewards is the most important motivation factor interrelated with job satisfaction while intrinsic factors are less significant. In terms of challenges, the Economic ones are the most important moderators namely the Drastic decline in the Value of salary causing a deteriorated purchasing power, followed by the health challenges namely Scarcity and increased prices of medical supplies. The Security challenges show no significant moderating impact.

Table 5.

Aggregated research results.

4.1. Interview Results’ Discussion

The most prominent themes deduced from the interviews were classified according to the number of times mentioned across all interviews and the number of LAF participants who mentioned the theme (See Table 6 below). These themes allow us to assess the most important challenges affecting service members namely economic, health, and security; motivation factors namely intrinsic factors of self-determination and achievement-motivation and extrinsic factors of expectancy-valence and reinforcement; job satisfaction outcomes including intrinsic, extrinsic, and general factors.

Table 6.

Interviews themes.

The findings of the challenges indicate that the overall faced challenges have a relatively high impact on LAF service members’ status. Most of the interviewees (37 out of 42) agreed on the effect of the economic challenges on the LAF with 78 times mentioning them across all interviews. Health challenges come next in importance with 31 respondents mentioning it a total of 62 times. A less agreed-on theme is the security challenges with 15 participants mentioning the term 29 times across all interviews.

In terms of motivation, the most important motivation dimension by the interviewed service members is the reinforcement as part of the extrinsic factors mentioned by 39 interviewees a total of 73 times. The second dimension is related to the expectancy-valence as part of the extrinsic factors with 36 participants mentioning the term 68 times. A less agreed-on motivation theme is self-determination as part of the intrinsic factors where less than half of the interviewees (18 out of 42) agreed on this factor and was mentioned 21 times across interviews. The least important dimension is achievement–motivation as part of the intrinsic factors, on which only 13 respondents mentioned it a total of 16 times.

Regarding job satisfaction, extrinsic factors come first in importance with 38 respondents mentioning them a total of 81 times. The second-ranked dimension of job satisfaction is related to general satisfaction factors which 31 interviewees agreed on 58 times mentioned across all interviews. The last ranked dimension of job satisfaction is intrinsic satisfaction which only 12 interviewees mentioned 18 times.

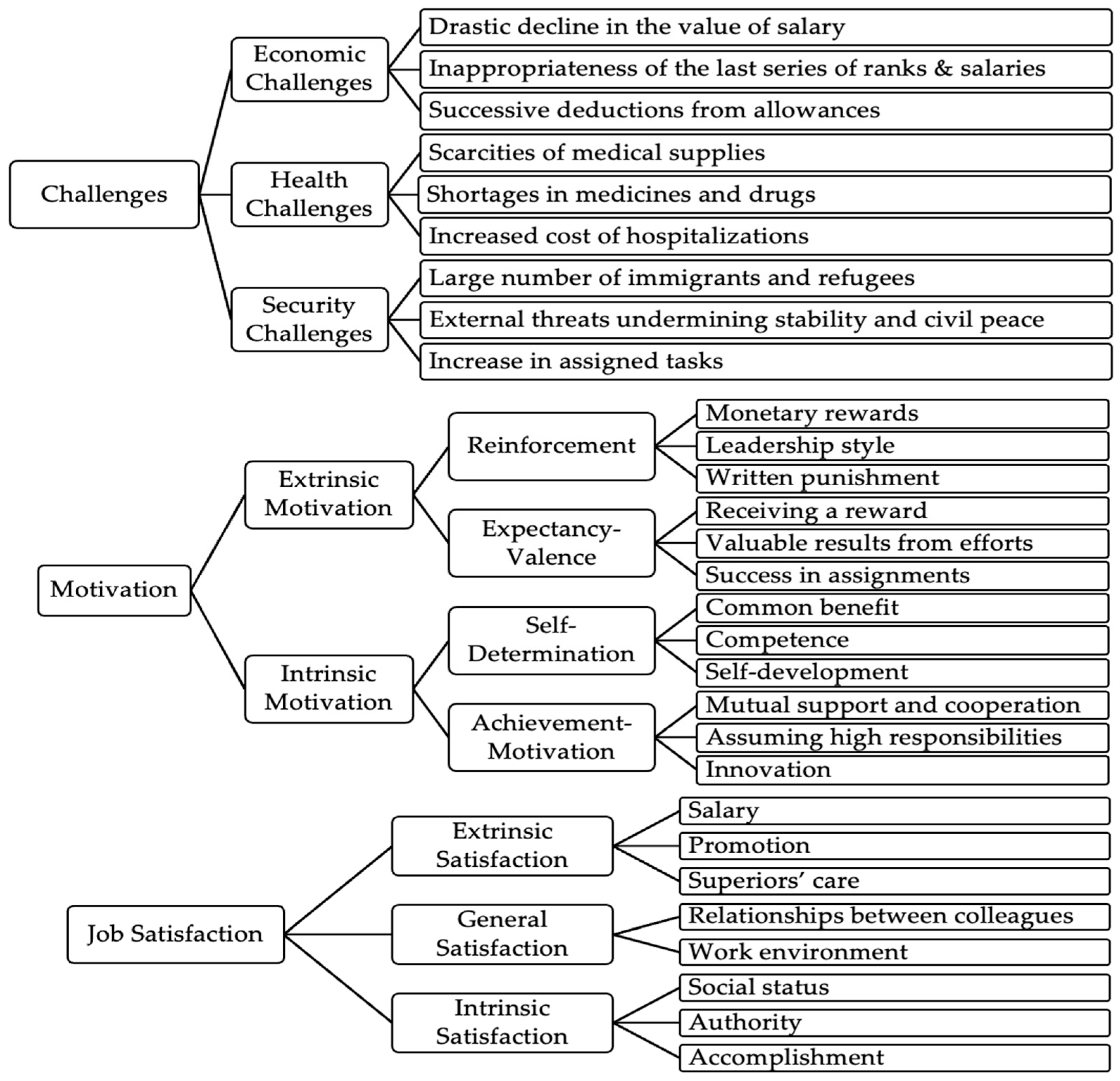

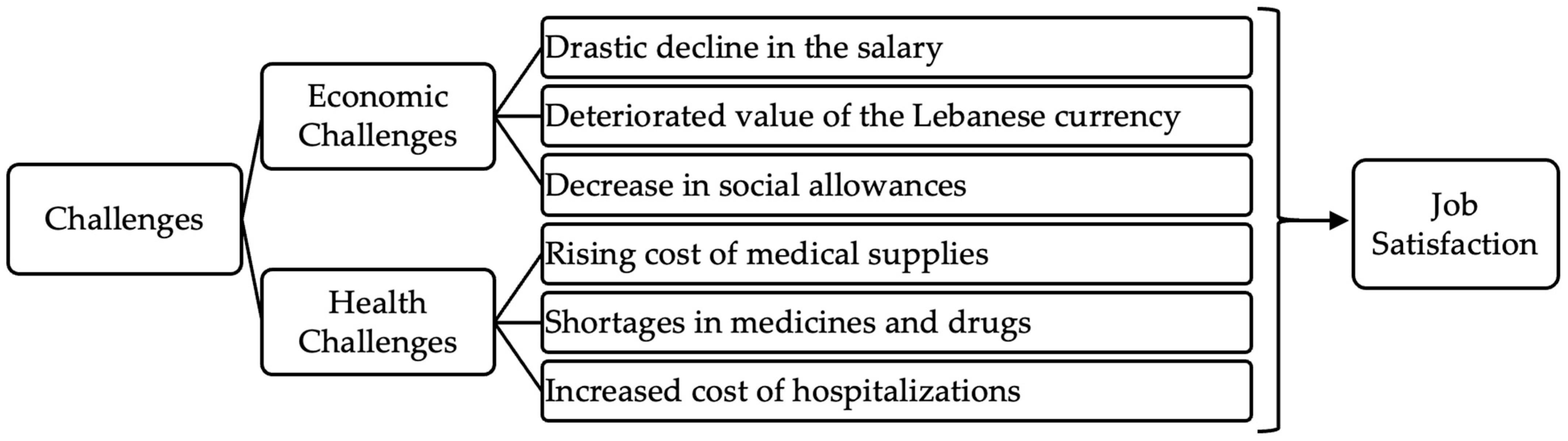

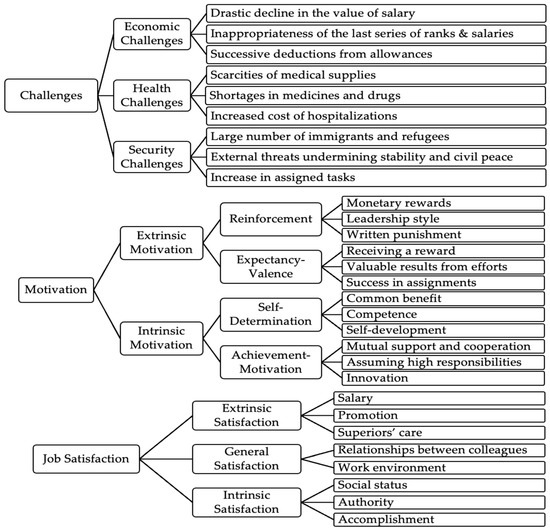

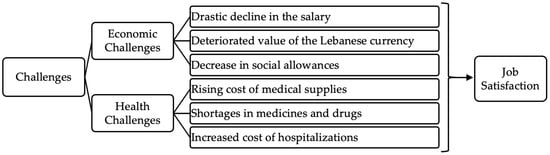

The detailed findings of the LAF service members’ challenges (See Figure 1 below) indicate that the most important economic challenges were the Drastic decline in the value of salary, followed by Inappropriateness of the last series of ranks and salaries, and Successive deductions from allowances. The most important health challenges reflect factors related to the Scarcity of medical supplies, Shortages in medicines and drugs, and Increased cost of hospitalizations. The security challenges dimension discusses factors namely the large number of immigrants and refugees, External threats undermining stability and civil peace, and an increase in assigned tasks because of the turmoil for demands.

Figure 1.

Thematic framework for the interviews.

Regarding motivation, the reinforcement aspect highlights factors such as Monetary rewards as the foremost consideration, trailed by Leadership style and Written punishment. The expectancy–valence factors center on Receiving a reward as the primary element, succeeded by Valuable results from efforts and Success in assignments. Self-determination encompasses factors like common benefits, competence, and self-development. Conversely, the least significant motivation pertains to achievement–motivation, encompassing factors such as mutual support and cooperation, assuming high responsibilities, and innovation.

Regarding job satisfaction, extrinsic satisfaction assesses factors namely salary, followed by promotion, and Superiors care. The general satisfaction factors discussed namely Relationships between colleagues, followed by the work environment. Intrinsic satisfaction discusses social status, followed by authority, and accomplishment.

4.2. Focus Group Results’ Discussion

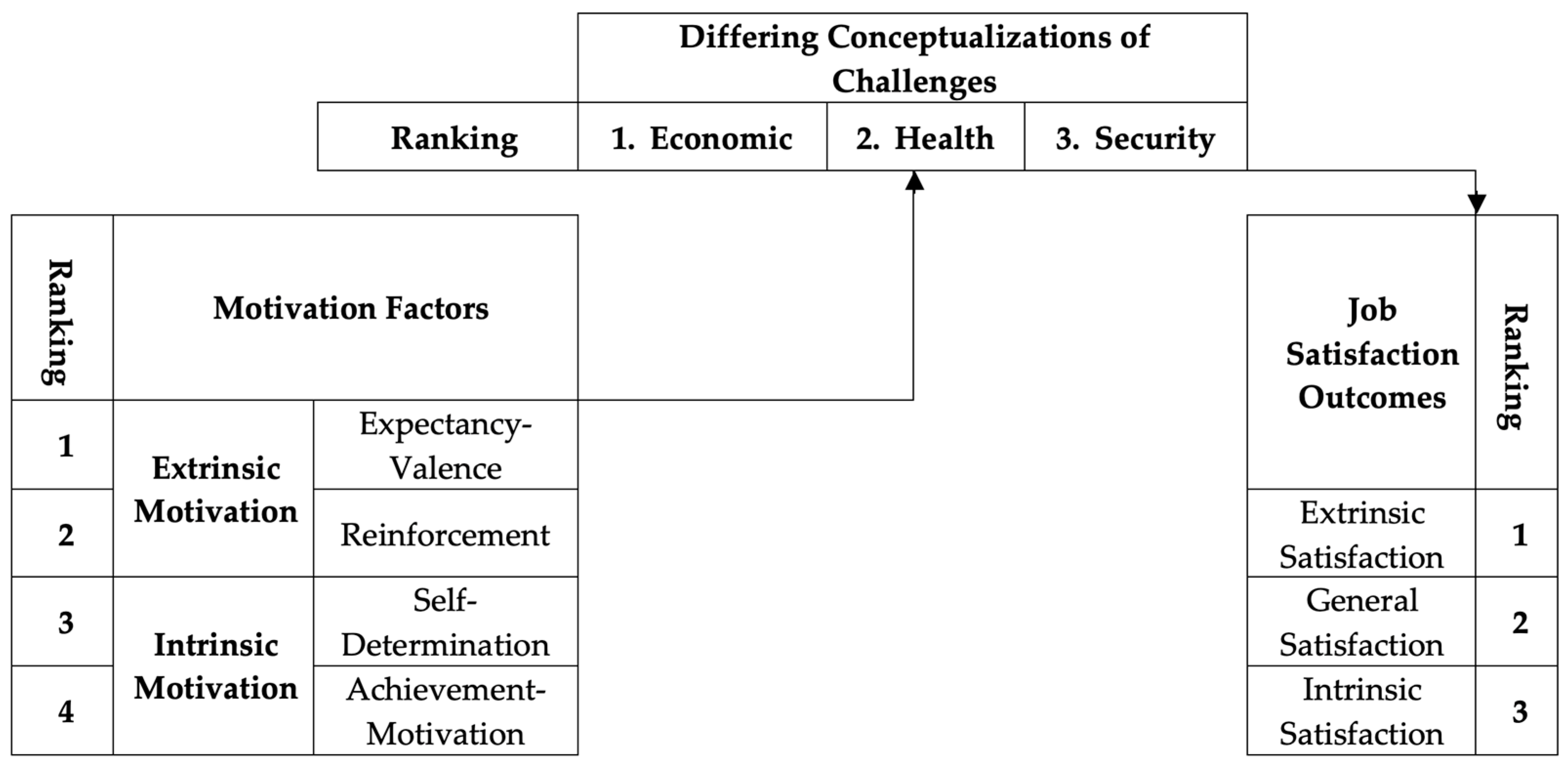

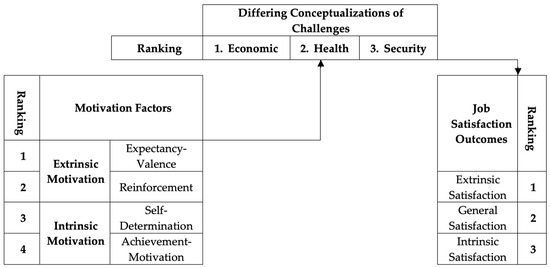

The focus group discussions gather common themes about the approaches and driving forces of motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges as well as their relationships which are comparable to the data sets from the interviews. These factors are ranked according to their importance as summarized in the Focus Group themes (See Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Focus group themes.

The results of faced challenges from the focus group analysis are like those of the interviews, where the most important challenges faced by service members are the economic, followed by health, and then security. Regarding the motivation factors, the main finding from the focus group analysis is like the interviews. Despite positive attitudes toward intrinsic factors on the theoretical level, the participants recognize various extrinsic factors that they perceive as more important on the practical level. Moreover, in contrast to the interviews, where the concentration is on the out-group perceptions towards factors of motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges, the members of the focus group establish common ground and negotiate a collective identity, using this in-group approach, to share their perceptions on the relationship between motivation and job satisfaction. The discussions show the importance of extrinsic motivation factors to increase job satisfaction more than intrinsic factors. The differentiation between the findings of the Focus Group with those of the interviews is that expectancy–valence factors come before reinforcement. The intrinsic factors kept their ranking with self-determination followed by achievement-motivation. In terms of their attitudes towards job satisfaction, the main finding emerging from the focus group analysis is, once again, that faced challenges impact the LAF service members’ general satisfaction, followed by extrinsic satisfaction, then intrinsic satisfaction.

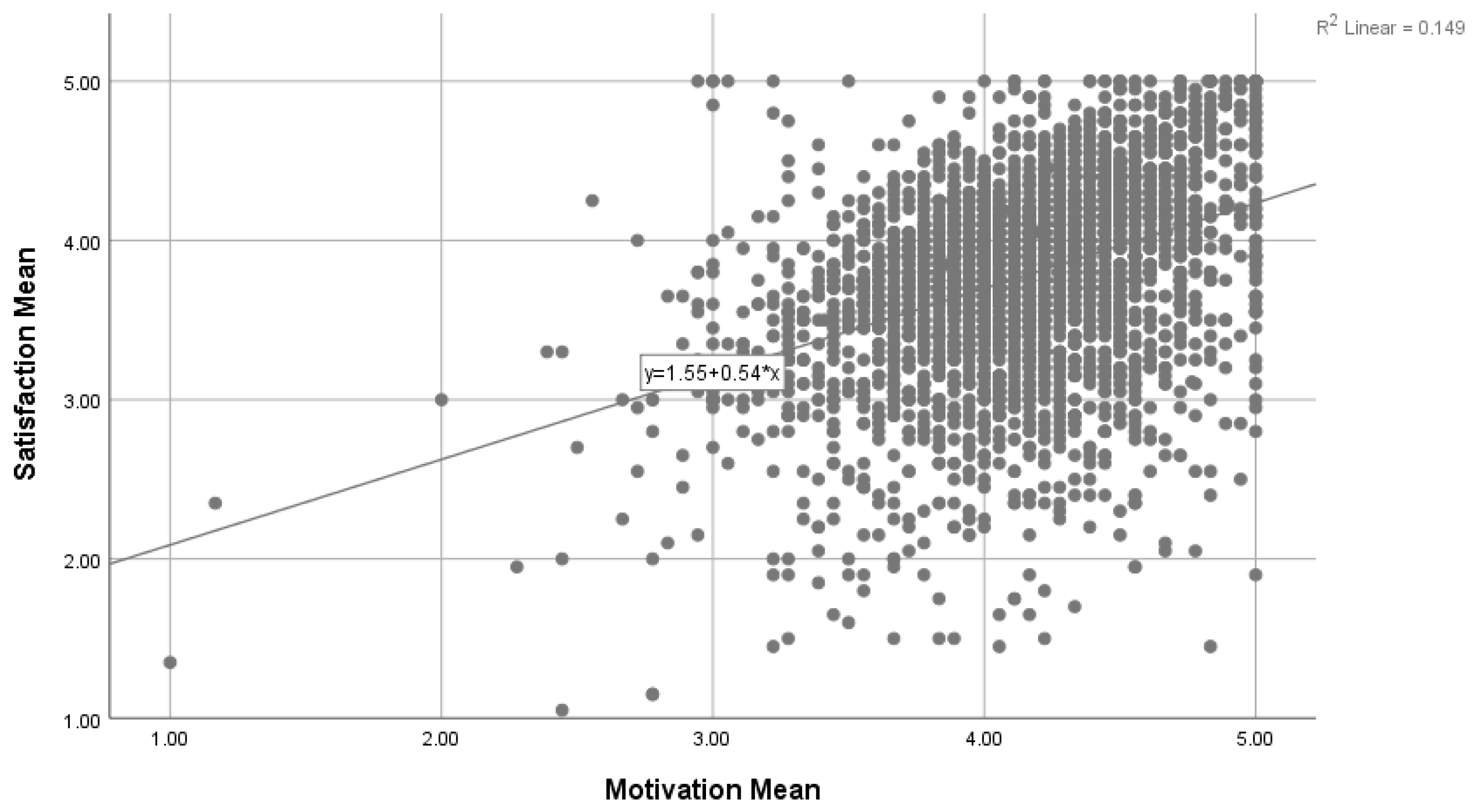

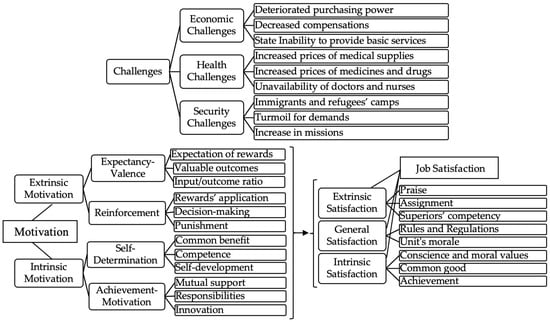

Regarding the detailed attitudes of LAF service members toward challenges (See Figure 3 below), the most important faced challenges are the economic factors namely the Deteriorated purchasing power, Decreased compensations, and the State’s inability to provide basic services. Health challenges are also of great significance in discussions specifically the Increased prices of medical supplies, Increased prices of medicines and drugs, and the Unavailability of doctors and nurses. Security challenges are less discussed concerning Immigrant and refugee camps, Turmoil for demands, and increase in missions. The finding on motivation relationship with job satisfaction indicates that the most important motivation factors to increase job satisfaction are extrinsic namely the expectancy-valence factors of Expectation of rewards, Valuable outcomes from efforts, and Input/outcome ratio. Reinforcement factors are next in terms of Rewards application, Decision-making, and Punishment. The intrinsic factors of self-determination are in terms of Common benefit, Competence, and Self-development. Achievement-motivation factors are Mutual support, Responsibilities, and Innovation. In terms of their attitudes towards job satisfaction, the most important extrinsic factors are Praise, Assignment, and Superiors’ competency. The general factors are Rules and regulations and the Unit’s morale. The intrinsic satisfaction factors are Conscience and moral values, Common good, and Achievement.

Figure 3.

Thematic framework for the focus group.

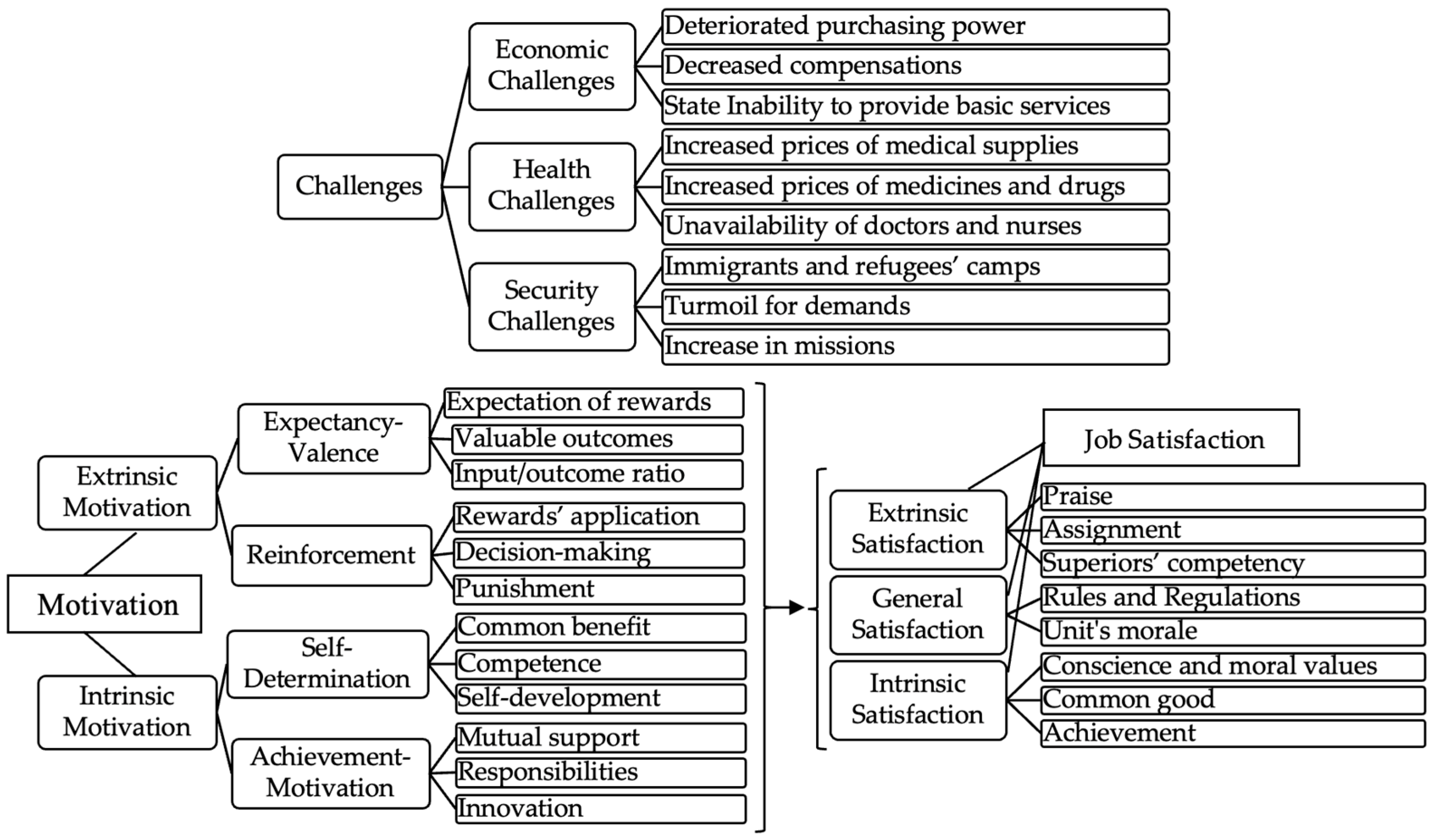

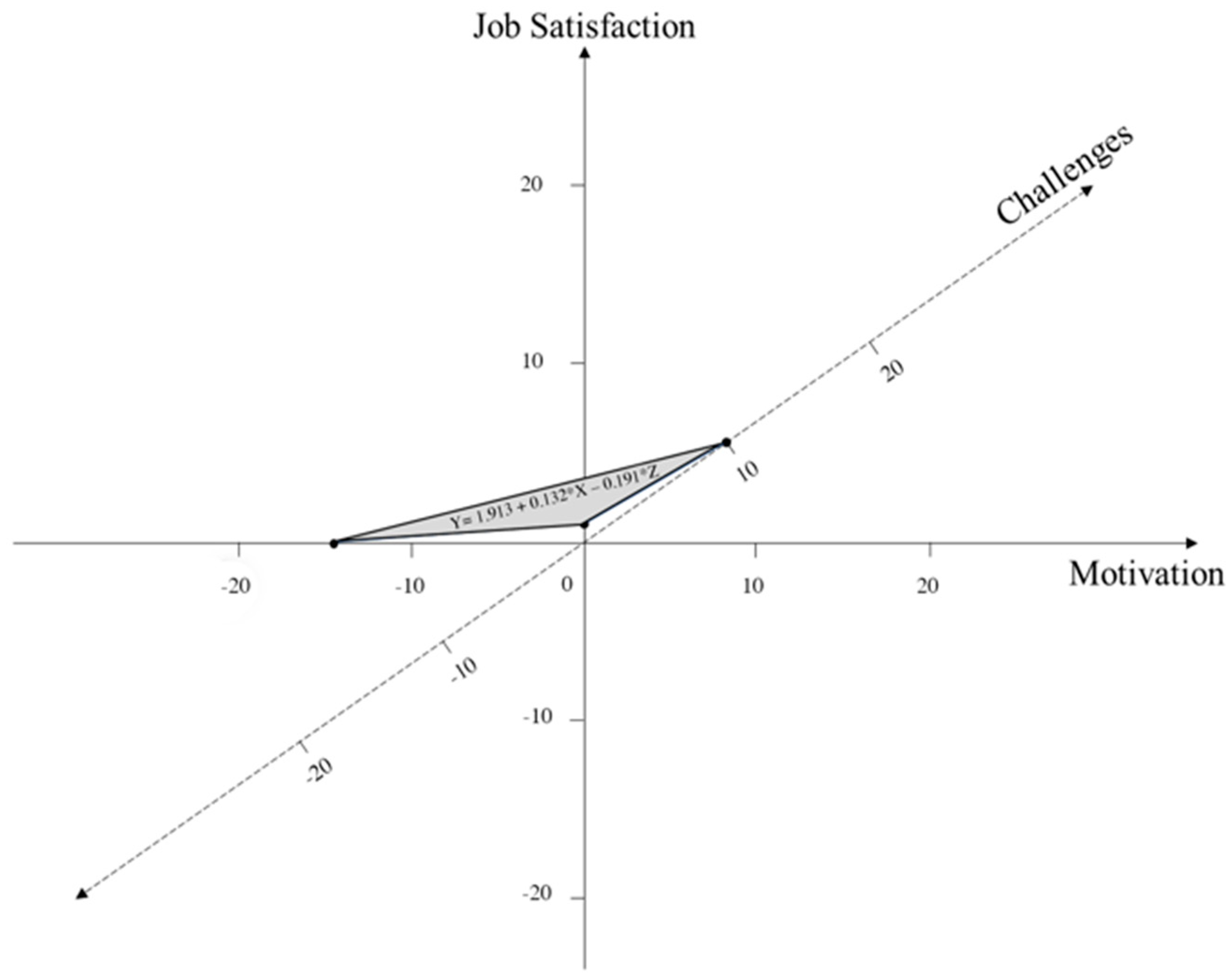

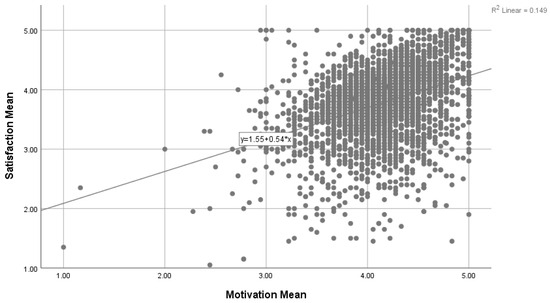

The survey results show a significant relationship between service members’ motivation and their job satisfaction (See Table 7 below) with a positive correlation of r = 0.386. The plot of the bivariate relation in the Simple Scatter graph (See Figure 4 below) shows that the higher motivation is, the higher job satisfaction will be (all t-values in absolute value > 1.96). The Regression Line defines the correlation equation between the two variables as Job Satisfaction = 1.551 + 0.537*Motivation. The Coefficient of Regression R2 in the Model Summary table shows that 14.9% of the variation in job satisfaction is explained by motivation. The all-Sig. values in both ANOVA and Coefficients tables explicate that this model is significant and can be relied upon with an accuracy of 100%.

Table 7.

Relation between motivation and job satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Simple Scatter of Motivation Mean by Job Satisfaction Mean.

Along these lines, the correlations between each motivation factor (i.e., expectancy–valence, reinforcement, self-determination, and achievement–motivation) with job satisfaction are all significant and positive with r = 0.353, 0.415, 0.261, and 0.236, respectively. The regression results confirm the results of the interviews and focus group showing that the most important motivation factors that impact job satisfaction are the Expectancy-Valence and Reinforcement as part of the extrinsic dimension, followed by self-determination and achievement-motivation as part of the intrinsic dimension with Coefficients of Regression R2 = 0.186, 0.173, 0.068, and 0.056, respectively (See Table 8 below). Hence, improvement in these dimensions will have a positive impact on service members’ job satisfaction, and conversely.

Table 8.

Motivation dimensions’ correlations with job satisfaction.

Regarding the detailed motivation factors’ impact on job satisfaction (See Figure 5 below), the findings indicate, like those from the Focus Group, that the most important factors to increase job satisfaction are extrinsic namely the expectancy–valence factors of Expectation of rewards, Valence of outcomes from efforts, and Input/outcome ratio. Reinforcement factors are Incentives’ application, Decision-making, and Punishment. The intrinsic factors of self-determination are in terms of Common benefit, Autonomy, and Relatedness. Achievement-motivation factors are Affiliation, Power, and Innovation.

Figure 5.

Thematic framework for motivation factors’ impact on job satisfaction.

4.3. Moderating Effect of Challenges

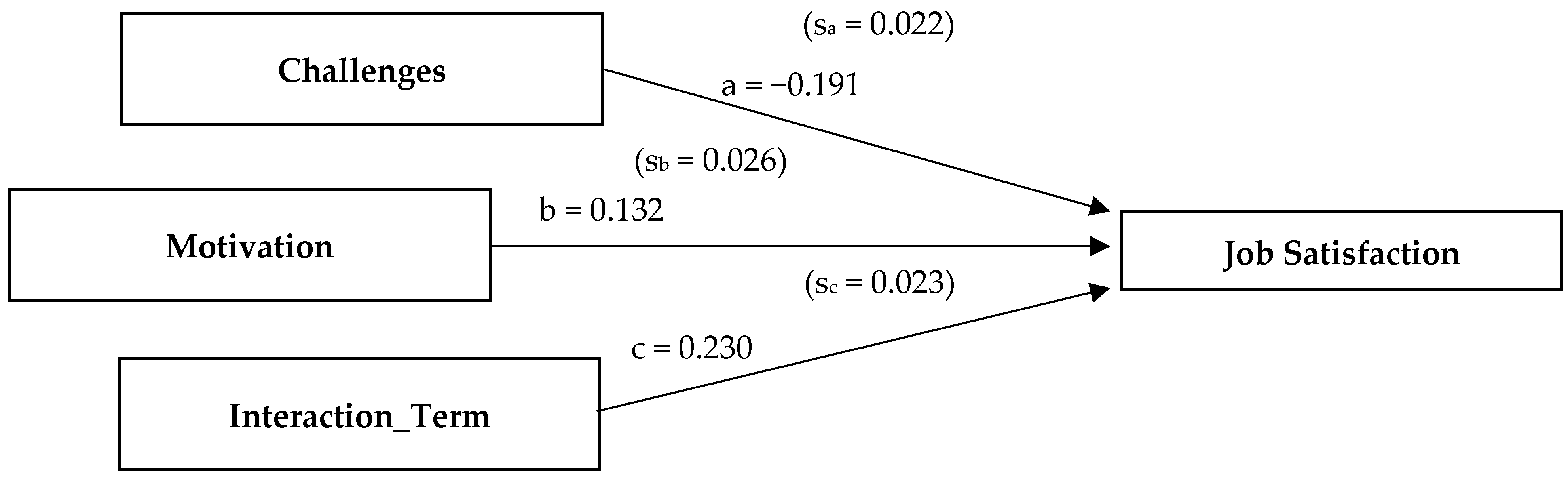

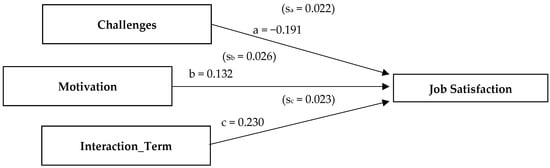

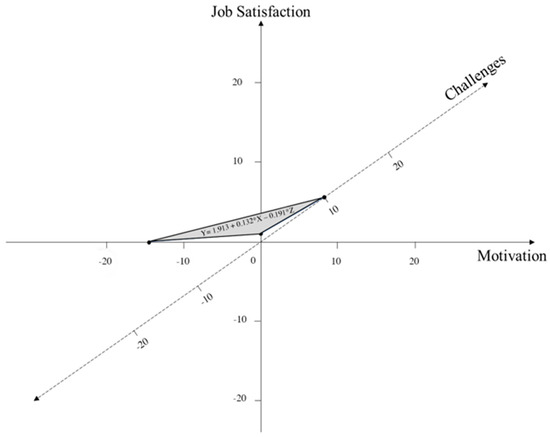

Using Baron and Kenny’s (1986) process, the moderation effect of challenges on the relation between motivation and job satisfaction is established. The all-sig values (p = 0.000) in Table 9 below with all t-values in absolute value where t > 1.96 show that this model can be relied on. The challenges play a moderating negative effect on the motivation-job satisfaction relation with an Unstandardized Coefficient B = −0.191 and a regression R2 = 17.3% (See Figure 6 below). The model of regression of the challenges is Job Satisfaction= 1.913 − 0.191*Challenges + 0.132*Motivation (See Figure 7 below). This implies that applying motivation factors can overcome the faced challenges to increase job satisfaction.

Table 9.

Moderating effect of challenges.

Figure 6.

Challenges moderating results unstandardized estimates.

Figure 7.

Challenges moderation interaction graph.

Along these lines, the moderating effect of each of the dimensions of challenges is examined and classified according to their importance (See Table 10 below). The most important dimension playing a negative role in the motivation–job satisfaction relationship is the economic challenges (B = −0.068) followed by the health challenges (B = −0.030) with respective correlations of r = 0.394 and 0.389 and regressions of 15.5% and 15.2%. No significance is verified for the security challenges, even though the model of regression for security challenges is significant with a negative Unstandardized Coefficient (B = −0.240) because the Sig. value of Interaction_TermSeC is p = 0.092 > 0.05.

Table 10.

Comparative ranking of challenges dimensions’ moderating results.

The detailed findings of the moderating impact of the challenges factors on the relationship between motivation and job satisfaction (See Figure 8 below) are comparable to those results from the interviews and Focus Group except for the security challenges which showed insignificance. The results indicate that the most important moderating economic challenges are the Drastic decline in salary, the Deteriorated value of the Lebanese currency, and the Decrease in social allowances. The most important health challenges reflect factors related to the Rising cost of medical supplies, Shortages in medicines and drugs, and Increased cost of hospitalizations.

Figure 8.

Thematic Framework for Challenges Factors’ Impact on Job Satisfaction.

4.4. Lessons Identified from the Lebanese Case

Learning from the complex dynamics of the Lebanese case and the findings on the LAF service members’ motivation and job satisfaction considering challenges may help in better understanding manpower efficiency and effectiveness and the larger HR phenomena in organizations. The research novel model may assist in the improvement of policymakers, planners, and practitioners’ policies, measures, structures, and programs in security institutions at the local, regional, and worldwide levels. Moreover, it represents a great research opportunity for any institution that is striving to optimize available resources and employment of means to face internal and external challenges. The lessons identified from the Lebanese case highlight the importance of providing competitive salaries and implementing recognition programs; ensuring that employees receive fair and competitive compensation; designing reward systems that align with employees’ expectations and performance; periodically reviewing and adjusting salary structures; providing adequate support for employees’ mental and physical well-being; creating a safe and secure work environment.

The first key lesson that can be drawn from Lebanon’s experience is the importance of providing competitive salaries and implementing recognition programs to enhance motivation and job satisfaction. The study’s results showed the significance of extrinsic motivators such as monetary rewards and praise in motivating individuals in the workplace. Monetary rewards, including salaries, bonuses, and financial incentives, serve as tangible indicators of an individual’s value and contribution to the organization. When employees perceive that their compensation is fair and competitive, it reinforces their motivation to perform well and achieve desired outcomes. In addition to monetary rewards, praise, and recognition contribute to employees’ sense of value and accomplishment. When people receive acknowledgment for their efforts, it boosts their morale, reinforces their sense of purpose, and fosters a positive work environment. Recognition programs that highlight outstanding performance, teamwork, and achievements can significantly enhance motivation and job satisfaction among employees. Effective compensation and recognition systems that align with employees’ needs and expectations can create a more engaged and motivated workforce, leading to improved manpower efficiency and effectiveness. Furthermore, fair and competitive compensation help in attracting and retaining talented individuals and ensuring their commitment to the organization’s goals and objectives. However, it is important to note that while extrinsic motivators are crucial, intrinsic motivators, such as meaningful work, autonomy, and opportunities for personal and professional growth, also play a vital role in fostering motivation and job satisfaction. Therefore, creating a holistic approach that balances both extrinsic and intrinsic factors can help maximize the motivation and job satisfaction of personnel.

Second, the LAF case highlights the significance of fair and competitive compensation which helps maintain employees’ job satisfaction. The results reveal the critical role of salary which emerges as the most important job satisfaction factor in the study. Salary serves as a fundamental aspect of employee compensation and is often a primary motivator for individuals to join and remain committed to an organization. It represents the financial value that employees perceive for their work and serves as a means of meeting their basic needs and fulfilling their financial obligations. Fair compensation implies that employees are rewarded appropriately for their skills, qualifications, and contributions to the organization. It provides a sense of equity and recognition for their efforts, leading to higher levels of job satisfaction and engagement. Ensuring fair and competitive salaries is crucial for organizations to attract and retain talented individuals. In highly competitive environments, inadequate compensation can result in talent attrition and difficulty in recruiting qualified candidates. On the other hand, when employees are satisfied with their salaries, they are more likely to be motivated, committed, and productive in their roles. Beyond job satisfaction, fair and competitive salaries also contribute to financial stability and security which positively impact individuals’ personal lives, reduce stress, and enhance their overall quality of life. When employees feel financially secure, they better focus on their work, resulting in increased efficiency and effectiveness. Regular review and benchmarking of salary structures ensure that organizations remain competitive in the market and aligned with industry standards. Providing transparent communication about salary policies and opportunities for growth and advancement can further enhance job satisfaction and motivate individuals to increase their performance. By recognizing the critical role of salary and prioritizing fair and competitive compensation practices, organizations can create an environment that fosters job satisfaction and improves manpower efficiency and effectiveness.

Another lesson from Lebanon’s experience is the importance of designing reward systems that align with employees’ expectations and performance. The findings showed the crucial impact of rewards, such as bonuses, promotions, and recognition as a motivating factor that is closely intertwined with job satisfaction of employees. Understanding and effectively utilizing rewards allows organizations to develop reward systems that effectively incentivize and motivate employees and can lead to improved overall levels of job satisfaction. It is important to establish clear criteria and transparent processes for determining and distributing rewards. This ensures that employees perceive the reward system as fair and equitable, which in turn enhances their motivation to perform at a high level. By aligning rewards with performance, organizations can create a sense of meritocracy, where employees feel that their hard work and achievements are recognized and rewarded appropriately. This recognition reinforces their motivation to excel in their roles and contribute to the organization’s success. Moreover, regular and timely recognition and rewards are also important as they can provide continuous positive reinforcement that encourages sustained motivation and job satisfaction. This can be achieved through ongoing performance evaluations, goal-setting processes, and feedback mechanisms that allow for the identification of deserving employees and permit the provision of appropriate rewards. Additionally, promoting a culture of appreciation and publicly acknowledging employees’ accomplishments and contributions enhances the effectiveness of rewards, fosters a positive work environment, and further motivates individuals to strive for excellence.

Moreover, the Lebanese case highlights the importance of periodically reviewing and adjusting salary structures to maintain employees’ overall job satisfaction. The study results consider economic challenges, such as a drastic decline in the value of salaries and the resulting deterioration in purchasing power, as significant moderators in the context of motivation and job satisfaction. Conducting regular assessments of the prevailing economic conditions and cost of living ensures that salaries remain competitive and reflective of employees’ financial needs. By doing so, organizations can mitigate the negative effects of economic fluctuations, which is crucial for their overall job satisfaction. In addition to salary adjustments, organizations can explore other strategies to support employees during economic challenges. This may involve providing financial counseling or assistance programs to help employees manage their finances effectively which can also help alleviate financial stress. Furthermore, transparent communication of salary policies and the rationale behind adjustments are essential as well as opportunities to provide feedback and raise concerns. This fosters trust, transparency, and a sense of fairness within the organization. Creating a work environment that addresses economic challenges helps to build a resilient and engaged workforce, even in the face of economic uncertainties.

Another lesson from Lebanon’s experience is the relevance of providing adequate support for employees’ mental and physical well-being. The study shows that health challenges, including scarcity and increased prices of medical supplies, are identified as important moderators that can impact individuals’ motivation and job satisfaction. Considering these challenges, implementing measures to ensure access to adequate healthcare resources and support enhances the health and well-being of employees. Healthy employees are more likely to be engaged, resilient, and productive in their roles. One crucial step organizations can take is to provide comprehensive healthcare benefits to their employees. This includes offering health insurance coverage that encompasses a wide range of medical services, ensuring that employees have access to quality healthcare without significant financial burden. By providing robust healthcare benefits, organizations demonstrate their commitment to the well-being of their employees, fostering a positive work environment and contributing to overall job satisfaction. Moreover, establishing partnerships with healthcare providers, suppliers, or relevant stakeholders ensures a steady and affordable supply of necessary medical resources. Additionally, organizations can explore options for bulk purchasing, negotiate favorable pricing agreements, or seek alternative suppliers to mitigate the impact of scarcity and rising costs. Implementing wellness programs that promote healthy lifestyles, offer mental health support services, and encourage work–life balance is equally important. This can include initiatives such as providing access to counseling services, offering flexible work arrangements, promoting stress management techniques, and organizing health promotion activities.

Last but not least, Lebanon’s experience showed that creating a safe and secure work environment is of utmost importance for organizations. While no significant moderating impact of security challenges was identified in the study, they still hold significant implications for overall organizational effectiveness. It is crucial for organizations to recognize and address any security concerns that may impact employee motivation and job satisfaction. When employees feel safe and secure in their workplace, they can focus on their tasks and responsibilities without undue stress or distractions. This, in turn, positively affects their motivation and job satisfaction. A secure work environment fosters a sense of trust, psychological welfare, and commitment among employees. Prioritizing security measures, protocols, and policies, providing necessary training and resources, and maintaining a strong security infrastructure help address potential risks and threats. Regular assessments and reviews of security systems should be conducted to identify and address any vulnerabilities. Additionally, encouraging open communication channels for employees to express any security concerns they may have provides avenues for reporting potential risks or incidents to promptly address them and reinforces employees’ perception of safety. This demonstrates that the organization takes their concerns seriously which creates a work environment that promotes trust, safety, and job satisfaction. This improved feeling of security contributes, in turn, to more employees’ engagement, productivity, and commitment to work resulting in higher levels of overall organizational effectiveness and efficiency.

The study implications for the theory were based on the research findings, the research limitations, and the gaps in the literature on motivation, job satisfaction, and challenges and represented important theoretical contributions to the body of knowledge in the local, regional, and international scholarships. The research contributed to filling the gap in social knowledge because of inter-construct relationships that have not been previously examined. The first important theoretical contribution of this research is its ability to incorporate new antecedents of motivation in the examination of their relation to job satisfaction in line with the popular extrinsic-intrinsic framework precisely extrinsic factors using expectancy–valence and reinforcement, and intrinsic factors using self-determination and achievement–motivation, in an empirical exploration of their impact on job satisfaction as an outcome. This represents novel models that define the role of these factors in the military setting, thus building a novel theory to explain how or why this relationship exists. In doing so, this research expands previous studies that have almost mostly based on the PSM theoretical perspective to examine motivating individuals in public organizations and understand the relationship between motivation and job satisfaction (Andersen et al. 2013). Additionally, another contribution is the research’s mixture between renowned theories of job satisfaction specifically the Equity theory of Adams (1963, 1965) and the Motivator–Hygiene theory of Herzberg et al. (1959) at the individual level, which helped better conceptualize the underpinning issues of job satisfaction and its factors’ role in the military setting and revealed the significance of employing these two theories and how they are beneficial in explaining the particular relationship in the context of armed forces. Lastly, another contribution of knowledge discovery is its effort to develop a conceptual theoretical model and integrate a relevant, reliable, and valid tool to measure the challenges along the economic, health, and security in an innovative process and a new form of specificity in the military as an additional variable in the camp of discussions. In that, the findings aid in identifying the fundamental mechanisms by which challenges affect how individuals’ motivation and job satisfaction are related. The research contributes to extending the existing literature concerning faced challenges and related outcomes as a moderating impact with a scarcity of studies in this field and only researchers found discussing it outside the research scope (Widmer et al. 2012; Okafor 2014).

In addition to the implications for theory, the study supports the development of structures of motivation to enhance service members’ job satisfaction and assist leaders, decision-makers, and planners in recommending practical solutions in the light of faced challenges. This represents a great research opportunity for institutions that are striving to optimize available resources and employment of means to face worsening circumstances. The first suggestion is for the LAF to strengthen the bonds among its service members by improving its cohesion structures through leadership empowerment and unit morale which enable the military institution to continue serving its purpose of defending the country, preserving security, and maintaining stability. The problem with the current system resides in the policies that enhance collective organizational engagement within the LAF units, which in turn help foster an excellent service climate that builds harmony and confidence between unit commanders and their staff on one hand, and service members on the other. Furthermore, this study advises the LAF leadership to update its rules and regulations for rewarding military personnel aiming to increase justice among its service members by tying rewards and compensation policies to their contributions, which in turn increases commitment and addresses the mismatch between motivating factors and expectations of their military institution. It was also clear from the study findings that the LAF service members perceived the salaries and compensations they receive as unsuitable in comparison to the amount of executed work, required tasks, and conducted missions in service, especially with the deterioration of the economic and financial situation. This would create enduring motivation which in turn stipulates service members’ satisfaction. Lastly, the study suggests that the LAF expand on its ongoing reforms in line with the IMF-required reforms to the public sector with a pressing focus on maximizing the resources available to maintain operational readiness and combat power. The findings signal the need to enhance their resilience to proactively accommodate adversity and hardship conditions. The problem with the current LAF force structure is its mismatch with the new missions and task requirements considering faced challenges and threats on the strategic, operational, and tactical levels. After all, a reengineering of the LAF should be the first concern of the LAF-G5, Planning that must incorporate these reforms in its policies, design, and planning efforts unconfined to boundaries. Moreover, the LAF should increase efforts to restructure its figures in each rank category to maximize the mission requirements while proposing policies and strategies with new possibilities for change to mitigate operational shortfalls and effectively execute tasks considering the current and future challenging OE requirements.

5. Conclusions

This research emphasizes the significance of HRM in organizations, particularly in the context of the military and the unique challenges it faces. Formulated in an extrinsic-intrinsic framework, the article topic is relevant for many cases across the globe that involve HR. It explores the dynamics of motivation and job satisfaction among service members in the LAF and draws valuable lessons from this case study to better understand manpower efficiency and effectiveness in organizations. The chosen theories have crucially influenced thoughts on motivation and job satisfaction and are the most pertinent in the military setting and the research framework. The importance of motivating personnel seems more important in the armed forces compared to civilians due to the unique nature of military service. Moreover, enhancing the job satisfaction of service members in the military is of a great deal compared to employees in the civilian sector. The study draws on literature from the fields of civilian aiming to contribute to theory in the armed forces field and HR development.

The study identifies the most significant motivating factors for LAF service members as monetary rewards and praise, highlighting the importance of providing competitive salaries and recognition programs. Additionally, salary emerges as the most crucial job satisfaction factor, emphasizing the need for fair and competitive compensation. The study also underscores the interrelation between motivation and job satisfaction, with the expectation of rewards playing a vital role. Addressing challenges is a key aspect, and the research highlights economic challenges, such as the decline in salary value, as the most important moderators. Periodically review and adjustments of salary structures can mitigate the impact of economic challenges on job satisfaction. Furthermore, health challenges, including scarcity and increased prices of medical supplies, are identified as important moderators. Prioritizing employee health by providing adequate healthcare benefits and support for well-being is also of great importance. While security challenges did not show significant moderating impacts, the study emphasizes the importance of recognizing and addressing any security concerns that may affect motivation and job satisfaction. Creating a safe work environment is crucial for overall organizational effectiveness.

This research contributes to the existing literature on HRM and provides valuable insights for policymakers, planners, and practitioners in security institutions. The findings from the Lebanese case provide valuable insights into motivating service members to improve job satisfaction and address challenges. By implementing these lessons, organizations can enhance manpower efficiency and effectiveness, leading to improved overall performance. The findings have broader implications for organizations across sectors, emphasizing the need to optimize resources and effectively address internal and external challenges. By understanding the dynamics of motivation and job satisfaction, organizations can better support their employees and promote their well-being, leading to enhanced performance and effectiveness.

In the context of military services, understanding and improving productivity and efficiency are critical components of operational readiness and effectiveness. While the lessons gleaned from the Lebanese case offer valuable insights into enhancing manpower efficiency and effectiveness, there exists a noticeable gap in addressing productivity and efficiency indicators within military organizations. Military operations are inherently complex, requiring precise coordination, resource utilization, and rapid decision-making. Incorporating productivity and efficiency metrics alongside considerations of motivation and job satisfaction can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how military personnel perform their duties under various conditions. By analyzing factors such as task completion rates, resource allocation, and mission outcomes, military leaders can better assess operational effectiveness and identify areas for improvement. Integrating productivity and efficiency metrics into the research model for future research can offer practical guidance for military policymakers, planners, and practitioners. This approach ensures that efforts to enhance motivation and job satisfaction among service members also contribute to improved operational performance and mission success. By identifying and mitigating areas of inefficiency, military leaders can maintain operational readiness and effectiveness even in the face of external disruptions, ultimately ensuring the continued success of military missions and objectives.