Expanding the Demand–Resource Model by an Anthropo-Organizational View: Work Resilience and the “Little Prince” and the “Self-Accountant” Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

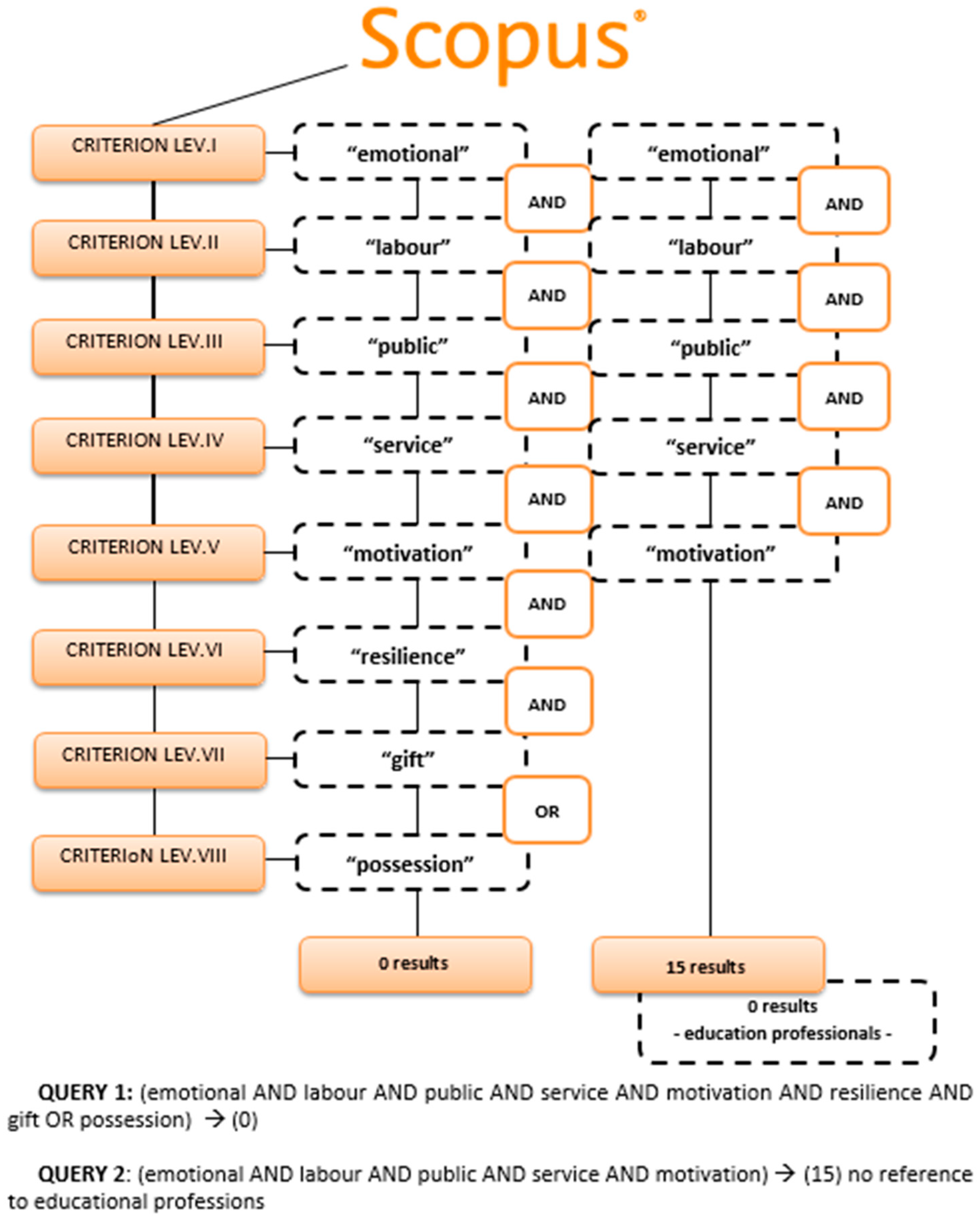

2. Literature Review: Contextualization

2.1. Emotional Labor and Sense-Making

2.2. Emotional Labor and New Public Management in the Italian Educational System

3. Methodological Aspects, Objectives, Gap Evaluation, and Research Questions

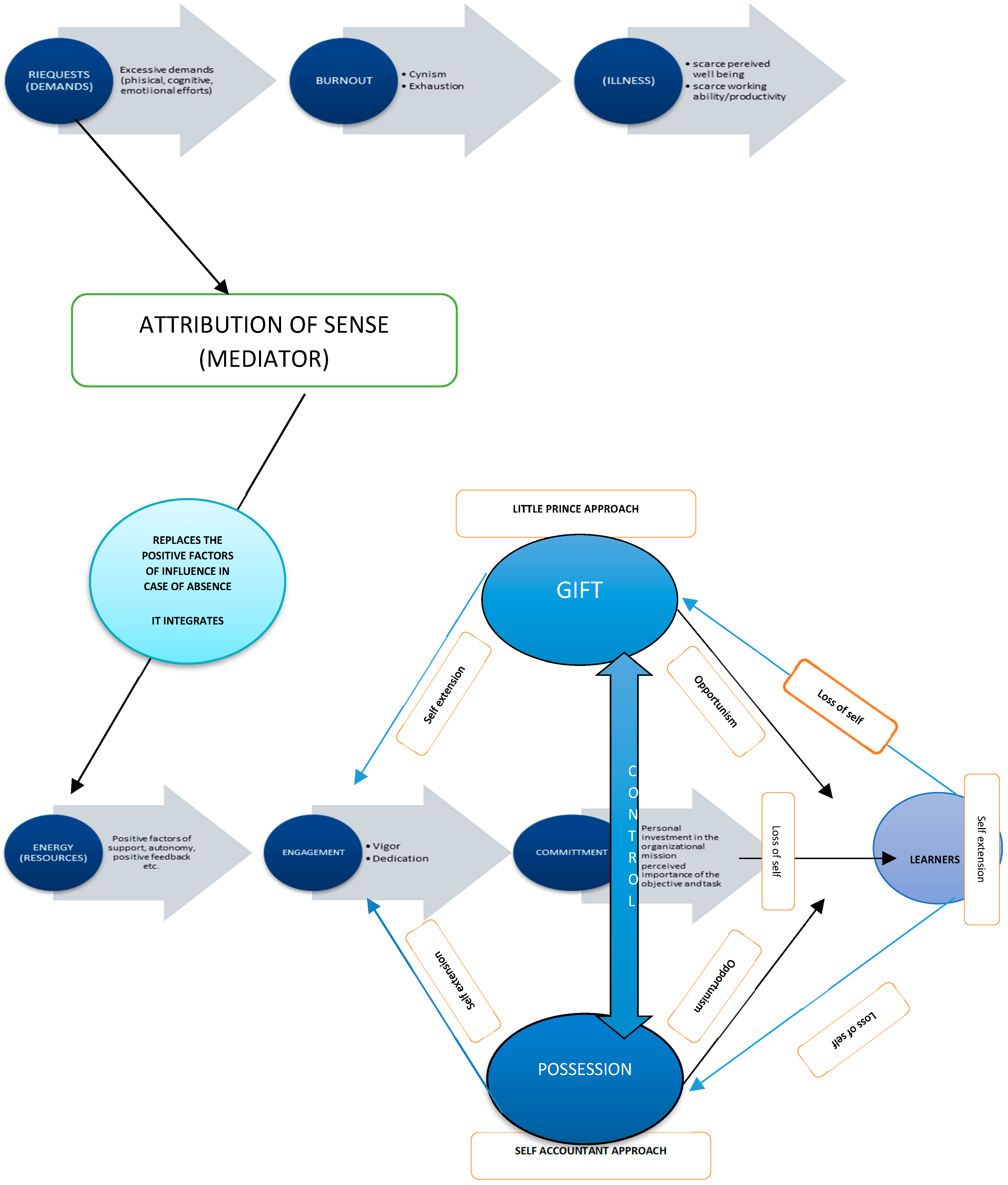

4. Interpretative Paradigm and Theoretical Frame: Prospects of Influencing Motivation and Job Satisfaction

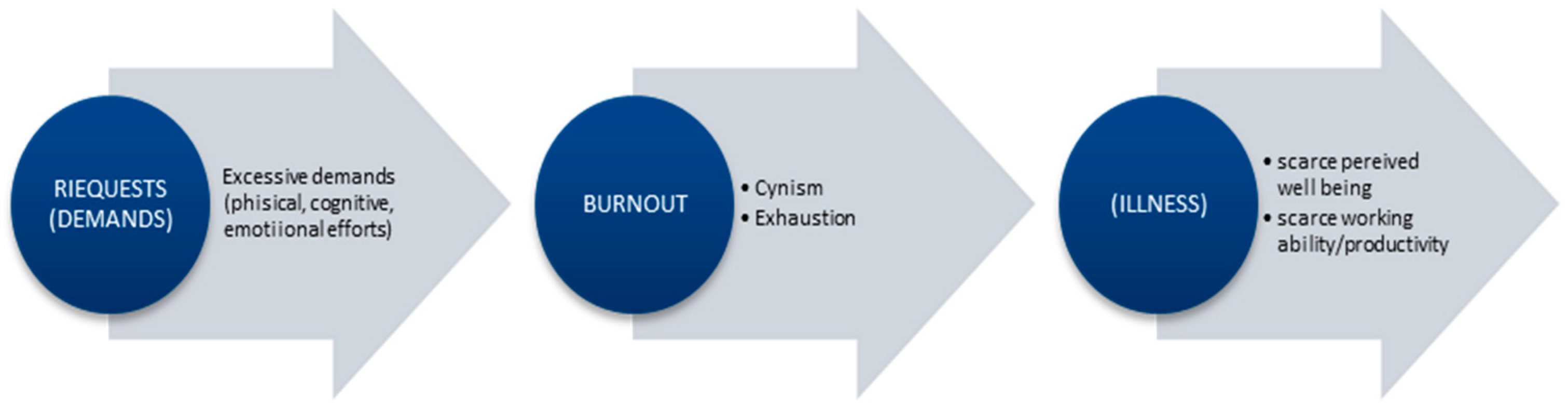

- (i)

- the first capable of outlining an “energetic process”, in which work demands create a frame of stress, burnout, and ill health conditions (Saks 2006; Maslach et al. 2001), declining as expedients (a) exhaustion and (b) cynicism, and

- (ii)

- the second capable of outlining a “motivational process”, in which work resources (understood as factors capable of reducing the burden of work) are directly proportional to the reduction in health costs and the improvement in work performance (Kahn 1990).

- (a)

- extension of the self as a gift;

- (b)

- extension of the self as possession.

- (a)

- reciprocity → gift → alter-beneficial/reflex-beneficial ← feedback

- (b)

- reciprocity → acquisition → self-beneficial/reflex-beneficial ← care

5. Summarized Results of Previous Empirical Analysis: Premise

Integrated Conceptual Model

6. Critical Discussion

- (i)

- The “little prince” approach;

- (ii)

- The “self-accountant” approach.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, Rebecca. 1998. Emotional dissonance in organizations: Antecedents, consequences, and moderators. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs 124: 229–46. [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, Bilal, Ahsen Maqsoom, Asad Shahjehan, Sajjad Ahmad Afridi, Adnan Nawaz, and Hassan Fazliani. 2020. Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, Bilal, and Waheed Ali Umrani. 2020. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 109–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, George A. 1982. Labor contracts as partial gift exchange. Quarterly Journal of Economics 82: 543–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, John. 2009. Public Value from Co-Production by Clients. Working Paper. Melbourne: Australia and New Zealand School of Government, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Mischel. 1969. Human emotion and action. In Human Action: Conceptual and Empirical Issues. Edited by Theodore Mischel. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arrowsmith, James, and Paul Marginson. 2010. The decline of incentive pay in British manufacturing. Industrial Relations Journal 41: 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Ronald H. Humphrey. 1993. Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity. Academy of Management Review 18: 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, Stephen, Ian Kessler, and Paul Heron. 2007. The consequences of assistant roles in the public services: Degradation or empowerment? Human Relations 60: 1267–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B. 2011. An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20: 265–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Michael P. Leiter, and Toon W. Taris. 2008. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress 22: 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Steve. 2004. Getting engaged. HR Magazine 49: 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, Russell W. 1988. Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, Paul S., and Michael J. Maloney. 1991. The importance of empathy as an interviewing skill in medicine. JAMA 226: 1831–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benington, John, and Mark Moore. 2010. Public Value: Theory and Practice. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bititci, Umit S. 2015. Managing Business Performance: The Science and the Art. Edinburgh: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Matt, and George T. Milkovich. 1998. Relationships among risk, incentive pay, and organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal 41: 283–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Tony, and Mel Ainscow. 2011. Index for Inclusion. Developing Learning and Participation in Schools. Bristol: Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education Supporting Inclusion, Challenging Exclusion. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, Rene Ten, and Hugh Willmott. 2001. Towards a post-dualistic business ethics: Interweaving reason and emotion in working life. Journal of Management Studies 38: 769–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, Stefano. 2016. Le Innovazioni Dirompenti. Turin: Giappichelli. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, Yvonne, Matthew Xerri, Ben Farr-Wharton, Kate Shacklock, Rod Farr-Wharton, and Elisabetta Trinchero. 2016. Nurse safety outcomes: Old problem, new solution—The differentiating roles of nurses’ psychological capital and managerial support. Journal of Advanced Nursing 72: 2794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardon, Melissa S., Charlene Zietsma, Patrick Saparito, Brett P. Matherne, and Carolyn Davis. 2005. A tale of passion: New insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. Journal of Business Venturing 20: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, Sadia, Bilal Afsar, and Farheen Javed. 2020. Employees’ corporate social responsibility perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: The mediating roles of organizational identification and environmental orientation fit. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Tom, and Per Lægreid. 2007. Transcending New Public Management: The Transformation of Public Sector Reforms. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Collie, Rebecca J., Jennifer D. Shapka, and Nancy E. Perry. 2012. School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology 104: 1189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saint-Exupéry, Antoine. 1961. The Little Prince. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach, Thomas. 2009. New Public Management In Public Sector Organizations: The Dark Sides of Managerialistic ‘Enlightenment’. Public Administration 87: 892–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Thomas, Elinor Ostrom, and Paul C. Stern. 2008. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. In Urban Ecology. Edited by John M. Marzluff, Gordon Bradley and Clare Ryan. Boston: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dudau, Adina, and Yvonne Brunetto. 2020. Managing emotional labour in the public sector. Public Money & Management 40: 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Gay, Paul. 2000. Praise of Bureaucracy: Weber-Organization-Ethics. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Chris. 2017. Emotional labour: Learning from the past, understanding the present. British Journal of Nursing 26: 1070–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr-Wharton, Ben, Joseph Azzopardi, Yvonne Brunetto, Rod Farr-Wharton, Natalie Herold, and Art Shriberg. 2016. Comparing Malta and USA police officers’ individual and organizational support on outcomes. Public Money & Management 36: 333–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr-Wharton, Ben, Yvonne Brunetto, Mathew Xerri, Art Shriberg, Stefanie Newman, and Joy Dienger. 2019. Work harassment in the UK and US nursing context. Journal of Management & Organization 28: 348–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, Stephen. 2012. Work: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fineman, Barbara, and Åsa Sturdy. 1999. The emotions of control: A qualitative exploration of environmental regulation. Human Relations 52: 631–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, Caterina, Licia Ciangriglia, Simona De Stasio, and Roberto Serpieri. 2015. Salute e Benessere degli Insegnanti Italiani. Milano: FrancoAngeli. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, Erich. 1976. To Have or To Be. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Gillman, Lucia, Robyn Kovac Jillian Adams, Annita House Anne Kilcullen, and Claire Doyle. 2015. Strategies to promote coping and resilience in oncology and palliative care nurses caring for adult patients with malignancy: A comprehensive systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports 13: 131–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, Erving. 1961. Asylums. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, Alicia A. 2000. Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, Adam. 2013. Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Peter. 2019. Teacher Merit Pay Is a Bad Idea. Jersey City: Forbes. [Google Scholar]

- Hakanen, Jari J., Arnold B. Bakker, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2006. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology 43: 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey-Beavis, Owen. 2003. Performance-Based Rewards for Teachers: A Literature Review. Paper presented at the 3rd Workshop of Participating Countries on OECD’s Activity Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers, Athens, Greece, June 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, Tracy G., and Tony Garry. 2003. An overview of content analysis. The Marketing Review 3: 479–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, Christopher. 1991. A Public Management For All Seasons? Public Administration 69: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Chih-Wei, Myung H. Jin, and Mary E. Guy. 2012. Consequences of work-related emotions: Analysis of a cross-section of public service workers. The American Review of Public Administration 42: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabareen, Yosef. 2009. Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definition and Procedure. The International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8: 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, William A. 1990. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal 33: 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, William A. 1992. To be fully there: Psychological presence at work. Human Relations 45: 321–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Andreas, and Michael Haenlein. 2019. Digital transformation and disruption: On big data, blockchain, artificial intelligence, and other things. Business Horizons 62: 679–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellough, J. Edward, and Haoran Lu. 1993. The paradox of merit pay in the public sector. Review of Public Personnel Administration 13: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskheli, Asadullah, Yushi Jiang, Syed A. Raza, Muhammad A. Qureshi, Komal A. Khan, and Javeria Salam. 2020. Do CSR activities increase organizational citizenship behavior among employees? Mediating role of affective commitment and job satisfaction. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 2941–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sangmook. 2012. Does person-organization fit matter in the public -sector? Testing the mediating effect of person-organization fit in the relationship between public service motivation and work attitudes. Public Administration Review 72: 830–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, Gail, and Sandra Leggetter. 2016. Emotional Labour and Wellbeing: What Protects Nurses? Healthcare 4: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, Gail, Siobhan Wray, and Calista Strange. 2011. Emotional labour, burnout and job satisfaction in UK teachers: The role of workplace social support. Educational Psychology 31: 843–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumenta, Maria. 2015. Public service motivation and organizational citizenship. Public Money & Management 35: 341–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, Irvine. 2009. New public management: The cruellest invention of the human spirit? Abacus 45: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, Alan, Julie Rayner, and Karin Lasthuizen. 2013. Ethics and Management in the Public Sector. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard. 1980. Thoughts on the relations between cognition and emotion. American Psychologist 37: 1019–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyun Jung. 2018. Emotional Labor and Organizational Commitment among South Korean Public Service Employees. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal 46: 1191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidner, Robin. 1999. Emotional labor in service work. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 561: 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mingjun, and Ya Liu. 2014. Development of public service motivation scale in primary and middle school teachers. China Journal of Health Psychology 3: 366–68. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Mingjun, and Zhenhong Wang. 2016. Emotional labour strategies as mediators of the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction in Chinese teachers. International Journal of Psychology 51: 177–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locke, Edwin A. 1976. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Edited by Marvin Dunnette. Chicago: Rand McNally, pp. 1297–349. [Google Scholar]

- London, Manuel. 1995. Giving feedback: Source-centered antecedents and consequences of constructive and destructive feedback. Human Resource Management Review 5: 159–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Xiaojun, and Mary E. Guy. 2014. How emotional labor and ethical leadership affect job engagement for Chinese public servants. Public Personnel Management 43: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, William H., and Benjamin Schneider. 2008. The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology 1: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, Christina, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Michael P. Leiter. 2001. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, Marcel. 2002. Saggio sul Dono. Forma e Motivo dello Scambio nelle Società Arcaiche. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Marshall W. 2002. Finding performance: The new discipline in management. In Business Performance Measurement: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J. Andrew, and Daniel C. Feldman. 1996. The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academy of Management Review 21: 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Gale M., Phylis Wakefield, Dorlene Walker, and Scott Solberg. 1994. Teacher preferences for collaborative relationships: Relationship to efficacy for teaching in prevention-related domains. Psychology in the Schools 31: 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, Donald P., and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2007. The role of organizations in fostering public service motivation. Public Administration Review 67: 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardella, Christian, Feliciano Iudicone, and Silvia Sansonetti. 2017. REST@Work, Reducing Stress at Work, Stress Lavoro Correlato: Un Rischio da Gestire Insieme. Münster: Olympus. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Elaine, and Carol Linehan. 2014. A Balancing Act: Emotional Challenges in the HR Role. Journal of Management Studies 51: 1257–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flynn, Janine. 2007. From New Public Management to Public Value: Paradigmatic Change and Managerial Implications. Australian Journal of Public Administration 66: 353–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, Dennis W., Philip M. Podsakoff, and Scott B. MacKenzie. 2006. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, Stephen P, Zoe Radnor, and Kirsty Strokosch. 2016. Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A Suitable Case for Treatment? Public Management Review 8: 639–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, Jatin, and Manjari Singh. 2015. Donning the mask: Effects of emotional labour strategies on burnout and job satisfaction in community healthcare. Health Policy and Planning 31: 551–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, Steven. 2015. Debate: Public service motivation, citizens and leadership roles. Public Money & Management 35: 330–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, Richard, and Bret Slade. 2006. Employee disengagement: Is there evidence of a growing problem? Handbook of Business Strategy 7: 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Lene Holm. 2014. Committed to the public interest? Motivation and behavioural outcomes among local councillors. Public Administration 92: 886–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, James L. 1996. Measuring public service motivation: An assessment of construct reliability and validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 6: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, James L., Jeffrey L. Brudney, David Coursey, and Laura Littlepage. 2008. What drives morally committed citizens? A study of the antecedents of public service motivation. Public Administration Review 68: 445–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, Christopher. 2009. Bureaucracies Remember, Post-bureaucratic Organizations Forget? Public Administration 87: 198–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, Richard A. 1997. Social Norms and the Law: An Economic Approach. The American Economic Review 87: 365–69. [Google Scholar]

- Power, Michael. 2003. Evaluating the audit explosion. Law & Policy 25: 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainero, Christian, and Giuseppe Modarelli. 2020. The concept of emotional labour within the boundaries of social responsibility. Journal of Governance & Regulation 9: 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, Julie, and Daniel E. Espinoza. 2016. Emotional labour under public management reform: An exploratory study of school teachers in England. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27: 2254–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, Tom, and Ed Snape. 2005. Unpacking commitment: Multiple loyalties and employee behaviour. Journal of Management Studies 42: 301–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, Bruce Louis, Jeffrey A. Lepine, and Eean R. Crawford. 2010. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal 53: 617–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, Amy. 2006. Everyone wants an engaged workforce how can you create it? Workspan 49: 36–9. [Google Scholar]

- Roblek, Vasja, Maja Meško, and Alojz Krapež. 2016. A Complex View of Industry 4.0. SAGE Open 6: 2158244016653987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romei, Piero. 1999. Guarire dal Mal di Scuola. Motivazione e Costruzione di Senso nella Scuola Dell’autonomia. Milano: La Nuova Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Rosi, Maja, David Tuček, Vojko Potočan, and Milan Jurše. 2018. Market orientation of business schools: A development opportunity for the business model of university business schools in transition countries. Ekonomie a Management 21: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, Babette. 2006. Help for the Helper: The Psychophysiology of Compassion Fatigue and Vicarious Trauma. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini, Renato, and Giuseppe Modarelli. 2015. Retribuzione e motivazione nella pubblica amministrazione oggi. RU 6: 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, Marshall, David Graeber, and Roberto Marchionatti. 2020. L’economia dell’età della Pietra. Milano: Elèuthera. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, Alan M. 2006. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology 21: 600–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, Peter, and John D. Mayer. 1990. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9: 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardi, Alberto, Enrico Sorano, Alberto Ferraris, and Patrizia Garengo. 2020. Evolutionary Paths of Performance Measurement and Management System: The Longitudinal Case Study of a Leading SME. Measuring Business Excellence 24: 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardi, Alberto, Enrico Sorano, Patrizia Garengo, and Alberto Ferraris. 2021. The role of HRM in the innovation of performance measurement and management systems: A multiple case study in SMEs. Employee Relations 43: 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1943. Being and Nothingness. A Fhenomenological Essay on Ontology. New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Schachter, Stanley, and Jerome Singer. 1962. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review 69: 379–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B. 2006. The balance of give and take: Toward a social exchange model of burnout. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 19: 75–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B. 2013. What is engagement? In Employee Engagement in Theory and Practice. Edited by Catherine Truss, Kerstin Alfes, Rick Delbridge and Amanda Shantz. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Isabel M. Martínez, Alexandra Marques Pinto, Marisa Salanova, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002a. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33: 464–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Marisa Salanova, Vicente González-Romá, and Arnold B. Bakker. 2002b. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 3: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, Brad, Thomas G. Reio, and Tonette S. Rocco. 2011. Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables. Human Resource Development International 14: 427–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Marisa, and Umit Sezer Bititci. 2017. Interplay between performance measurement and management, employee engagement and per-formance. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 37: 1207–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, Steven M., and Dennis S. Charney. 2018. Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steelman, Lisa A., and Kelly A. Rutkowski. 2004. Moderators of employee reactions to negative feedback. Journal of Managerial Psychology 19: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, Carol S., and James L. Perry. 1996. Organizational commitment: Does sector matter? Public Productivity and Management Review 19: 278–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockard, Jean, and Michael Bryan Lehman. 2004. Influences on the satisfaction and retention of 1st-year teachers: The importance of effective school management. Educational Administration Quarterly 40: 742–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, Sandra, and Frans L. Leeuw. 2002. The performance paradox in the public sector. Public Performance and Management Review 25: 267–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, Cheryl J., and Cary L. Cooper. 1996. Teachers under Stress. Stress in the Teaching Profession. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, Dave. 1997. Human Resource Champions. Boston: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele, Wouter. 2011. Who wants to deliver public service? Do institutional antecedents of public service motivation provide an answer? Review of Public Personnel Administration 31: 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, Adele Banks, and Ian Noonan. 2018. The Trojan War inside nursing: An exploration of compassion, emotional labour, coping and reflection. British Journal of Nursing 27: 1192–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weick, Karl E., Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, and David Obstfeld. 2005. Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science 16: 409–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, Amy S. 1999. The psychosocial consequences of emotional labor. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 561: 158–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Hongbiao. 2015. The effect of teachers’ emotional labour on teaching satisfaction: Moderation of emotional intelligence. Teachers and Teaching 21: 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, Robert B. 1985. Emotion and facial efference: A theory reclaimed. Science 228: 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamagni, Stefano. 2008. L’economia del Bene Comune. Roma: Città Nuova. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, Dieter. 2002. Emotion Work and Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Literature and some conceptual con-siderations. Human Resource Management Review 12: 237–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, Dieter, Claudia Seifert, Barbara Schmutte, Heidrun Mertini, and Melanie Holz. 2001. Emotion Work and Job Stressors and Their Effects on Burnout. Psychology & Health 16: 527–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, Dieter, Christoph Vogt, Claudia Seifert, Heidrun Mertini, and Amela Isic. 1999. Emotion Work as a Source of Stress: The Concept and Development of an Instrument. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 8: 371–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Self-Accountant | Little Prince | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aphorism—Metaphor | Possession Dynamic | Gift Dynamic | Loss Dynamic | Explanation |

| (1) If someone loves a flower, of which there is only one specimen in millions and millions of stars, this is enough to make him happy when he looks at it. | X | X | X | The dynamics of possession reside in the reflected (given) happiness of admiring the unique flower possessed; the dynamic of the gift lies in the process of triggering happiness, which causes a loss of extension of the self by the donor (rose—object of the work). |

| (2) But if the sheep eats the flower, it’s as if for him all of a sudden, all the stars go out! | X | X | X | The dynamic of possession lies in the action of eating the rose, which is given to the sheep. Again, there is a loss of self-extension in gift-giving concomitant with the sense of loss and possession. |

| (3) “And what do you do with five hundred million stars?” “What do I do with it?” “Nothing. I own them.” “Do you own the stars?” “Yes! When you find a diamond that doesn’t belong to anyone, it’s yours. When you find an island that belongs to no one, it’s yours. When you have an idea for the first one, you get it patented, and it’s yours. And I own the stars, because no one before me has ever dreamed of owning them.” | X | X | The acquisition of several thousand stars, in their unusability, produces an effective dynamic of possession concomitant with a feeling of loss (in the book, we refer to the action of keeping the accounting records updated on the number of stars owned). While the dynamics of the gift, expressed according to the identification of the “little prince” approach, is easily understandable, the authors propose the identification of the “self-accountant” approach in relation to this particular case deriving from a chapter in the book by A. de Saint-Exupéry (1961) that is inherent in the planet inhabited precisely by the “accountant”, who by counting the stars and keeping their updated registers, in fact, owns them. | |

| (4) “I”, said the little prince, “have a flower that I water every day. I own three volcanoes whose chimneys I sweep every week. Because I sweep the fireplace even the one that’s off. You never know. It is useful to my volcanoes, and it is useful to my flower that I have them.” | X | X | The dynamics of possession in this case shift to the flower, which is watered every day (gift) and to the volcanoes, which are swept away every week (gift). In this case, the dynamics are concomitant both as regards the possession and as regards the gift, since the utility (the loss of extension of the self by the two subjects) contributes to a beneficial/positive action of the possession. | |

| (5) What does “tame” mean? “It’s something long forgotten. It means creating bonds.” “Creating bonds?” “Of course,” said the fox. “You, until now, are to me but a little boy equal to a hundred thousand little boys. And I don’t need you. Nor do you need me. I am to you but a fox equal to a hundred thousand foxes. But if you tame me, we will need each other. You will be unique to me in the world, and I will be unique to you in the world.” And when the hour of departure drew near: “Ah!” said the fox, “.. I will cry.” | X | X | X | The creation of a bond finds in itself both the dynamics of possession and that of the gift with the aggravating feeling of loss identified in the reciprocal need connected to crying. |

| (6) “You are beautiful, but you are empty”, he said again. “I can’t die for you. Certainly, any passerby would believe that my rose looks like you, but she, she alone, is more important than all of you, because it is she that I watered. Because it is my rose.” “It’s the time you lost for your rose that made your rose so important.” | X | X | X | The dynamic of possession, in the creation of the bond, is inherent in the gift and in the fear of loss. This makes it possible to make the rose (the object of the work) to which the gift is directed (time) unique, also revealing the sensation of loss of part of the extension of the self bidirectionally (donor/possessor-recipient; recipient-donor/possessor. Lost time and protective actions (e.g., watering) return the projection of work onto the produced/possessed object, thus qualifying its importance and identifying the devastating features of the loss. |

| (7) “What makes the desert beautiful,” said the little prince, “is that somewhere it hides a well.” | X | X | X | The desert hides (gives) a well from (to) the seeker (the one who works to look for it) and who therefore can enjoy and dispose of the benefit of possessing, while losing part of the extension of his self. In the enjoyment of the object, there is a dynamic of reciprocal gift, which is also not without loss of extension of the self. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Modarelli, G.; Rainero, C. Expanding the Demand–Resource Model by an Anthropo-Organizational View: Work Resilience and the “Little Prince” and the “Self-Accountant” Approach. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070132

Modarelli G, Rainero C. Expanding the Demand–Resource Model by an Anthropo-Organizational View: Work Resilience and the “Little Prince” and the “Self-Accountant” Approach. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(7):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070132

Chicago/Turabian StyleModarelli, Giuseppe, and Christian Rainero. 2024. "Expanding the Demand–Resource Model by an Anthropo-Organizational View: Work Resilience and the “Little Prince” and the “Self-Accountant” Approach" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 7: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070132