Review of Sustainability Accounting Terms

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- An empty buzzword blurring the debate;

- (2)

- A broad umbrella term bringing together existing accounting approaches dealing with environmental and social issues;

- (3)

- An overarching measurement and information management concept for the calculation of corporate sustainability;

- (4)

- A pragmatic, goal driven, stakeholder engagement process that attempts to develop a company-specific and differentiated set of tools for measuring and managing environmental, social, and economic aspects, as well as the links between them.

2. Literature Review

- The first stage of research is based on three different sets of bibliometric data from 1945–2019 (the number of publications held as source items in the Web of Science; geographical origin of research; ranking of the publications by author). According to the author (Zyznarska-Dworczak 2020),

- The first studies on sustainability reporting and accounting date back to the 1990s;

- The beginnings of sustainability accounting developed in a mesoeconomic and macroeconomic approach (Gray 2002; Lodhia and Sharma 2019) and provided accounts to society of their resource use;

- The increase in research on reporting is more dynamic than that in accounting research, and it may be concluded that the role of sustainability accounting does not arise from sustainability reporting;

- The diverse interest in sustainability accounting and sustainability reporting by country may indicate the different aspects of sustainability accounting and reporting and the difficulty in distinguishing between sustainability reporting and accounting (and their other different forms and terms); furthermore, the different interest in sustainability accounting and reporting can be also interpreted as a niche in sustainability accounting research in Europe.

- The second stage of research reflects the most cited articles in the Web of Science database relating to sustainability accounting research from 1996–2019. According to the author (Zyznarska-Dworczak 2020), the publications with the highest citation rates (Gray 2002; Burritt and Schaltegger 2010; Wood et al. 2015; Schaltegger and Burritt 2006; Chen and Roberts 2010; Lehman 1999) differ in their approaches to sustainability accounting. These approaches are summarized in Table 3.

- Environmental financial accounting refers to the preparation of environmental financial reports for external audiences using generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP); it mainly includes the estimation and public reporting of all significant and financially material environmental information such as significant environmental costs, liabilities, and contingencies. The focus of environmental management accounting is internal.

- Environmental management accounting is the process of identifying, collecting, and analysing information about environmental costs and performance to help an organisation’s decision making (Environmental Protection Agency 1995).

- “Environmentally differentiated conventional accounting” as a part of conventional accounting, measuring environmentally induced impacts on a company in monetary terms;

- “Ecological accounting” as an accounting system that refers to the physical impacts of a company on the environment.

- Internal ecological accounting systems are designed to collect information, expressed in terms of physical units, about ecological systems for internal use by management;

- External ecological accounting systems are designed to collect and disclose the data for external stakeholders interested in environmental issues;

- Other ecological accounting systems, which also measure data in physical units, provide a means for regulators to control compliance with regulations.

- Some studies in the literature see social accounting in a broader sense and just assimilate it to CSR, considering them to be the same thing;

- Other scholars regard it from an ethical point of view (what an entity should do to be accountable);

- Others simply identify social accounting as aiming to help society by providing different facilities to entities and recording their activities;

- But there is also a part of the literature that supports a negative relationship between reporting and responsibility, regarding social practices.

3. Results

3.1. Defining the Keywords

3.2. Relationships between Keywords

- From the data, based on the analysis of the co-occurrence of keywords, we generated a set of all keywords identified by VOSviewer in the data; from WoS data, it was a set of 22,801 keywords, and from Scopus data, it was a set of 10,325 keywords. From the given files, we created a VOSviewer thesaurus file, which was used to merge different variants of a keyword and also to ignore irrelevant terms (see Table 7 and Table 8).

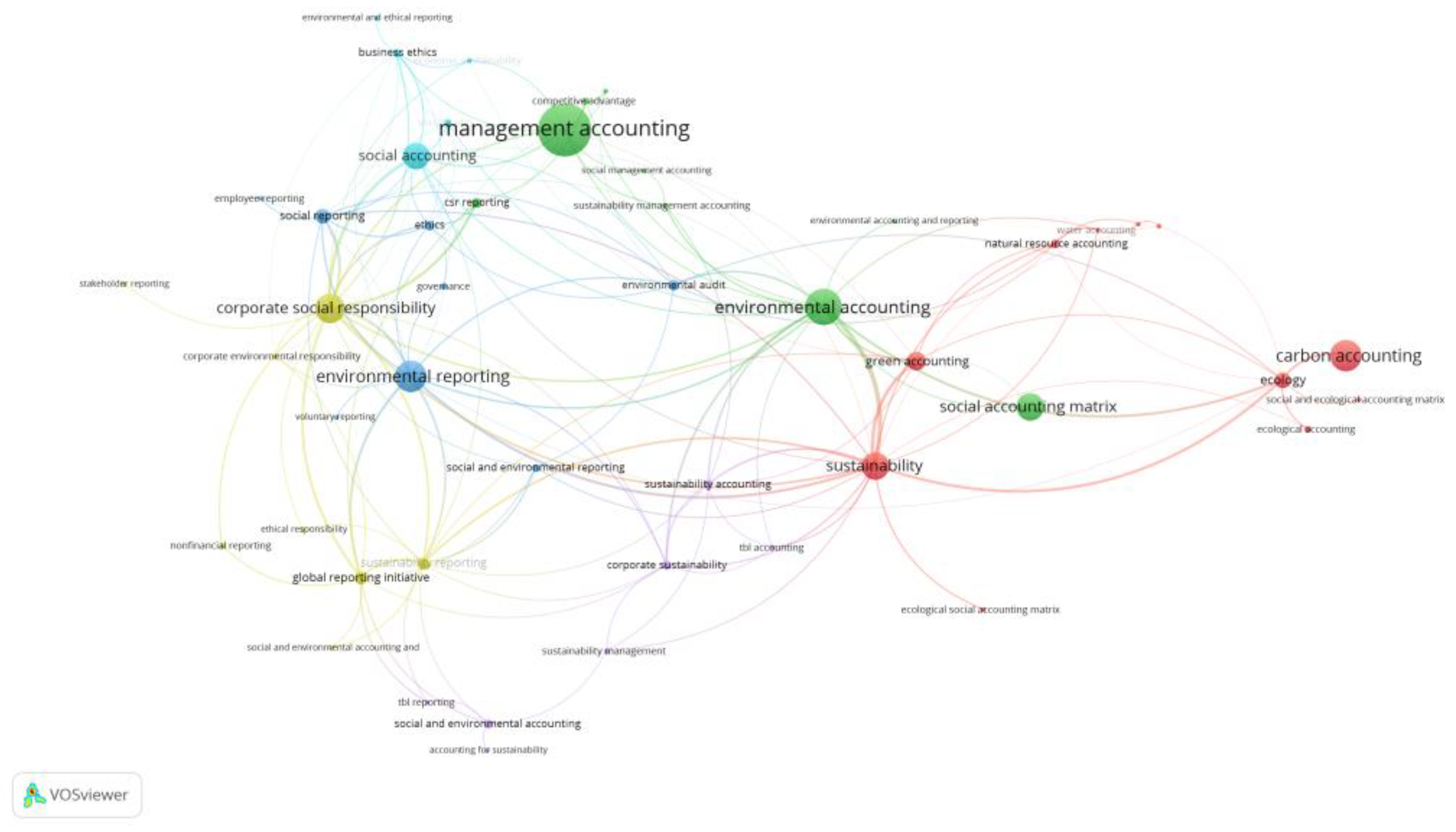

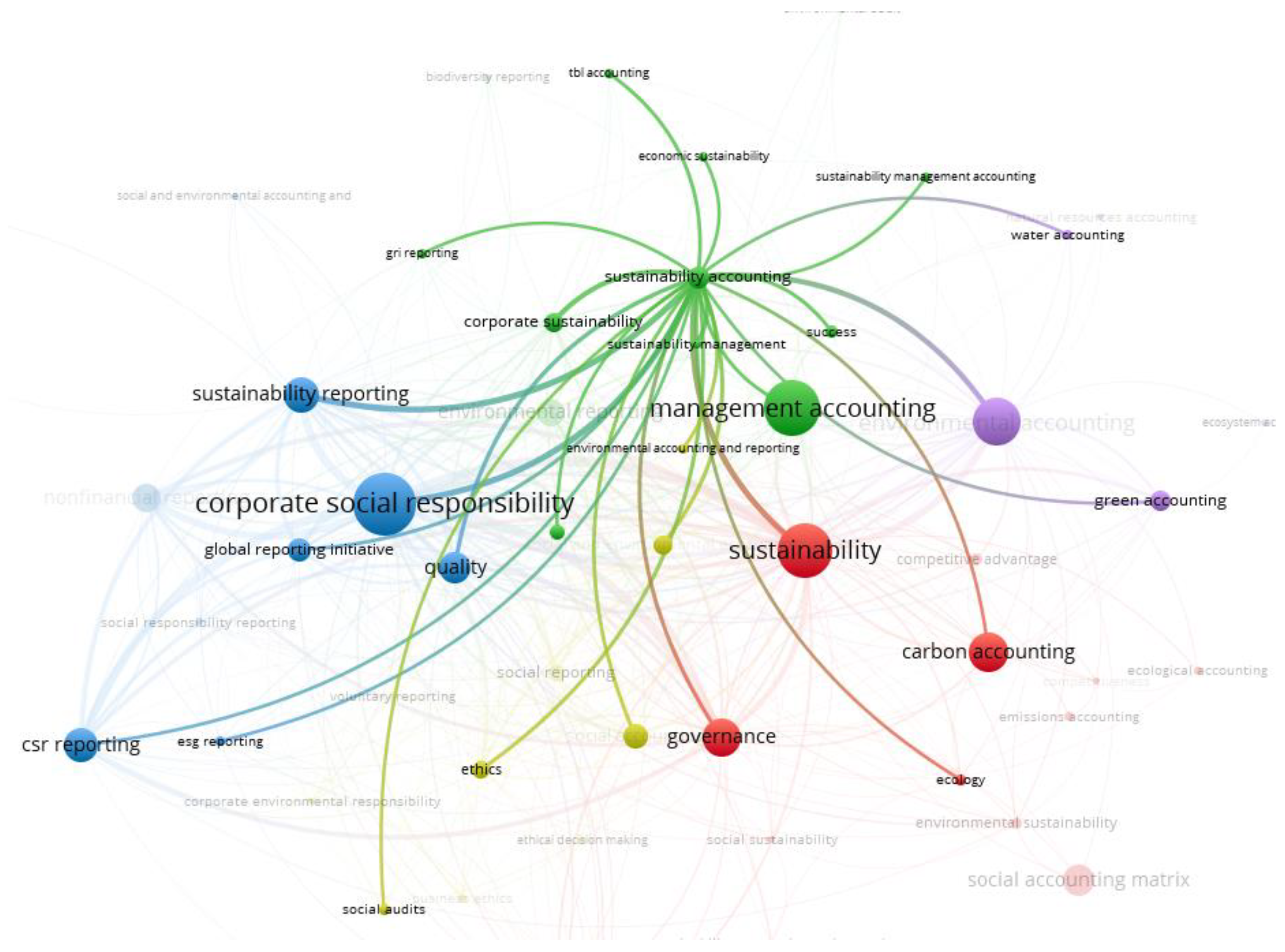

- We created two keyword co-occurrence maps (see Figure 1 and Figure 2) based on exported bibliographic data under the condition that the minimum number of occurrences of a keyword was set at five and the total link strength was at least 1 (52 keywords met the threshold for bibliographic data from WoS and 49 met the threshold for bibliographic data from Scopus).

4. Research Methodology

- We defined keywords in the field of accounting (see Table 6).

- We had each of the defined words searched first in the given database (WoS, Scopus).

- When searching the WoS database, we used WOS Field Tags Topic (TS), which searches the title, abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus. To find documents that contained an exact phrase, we enclosed the phrase in quotation marks (example for accounting for the environment: “accounting for the environment”; query link: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/b11bd265-d94f-4f55-b4c3-61b59f4fca52-caea992e/date-ascending/1 (accessed on 16 January 2024)).

- For the terms, we also considered the possibilities of different wording and use of abbreviations, e.g., “Triple bottom line accounting” or “TBL accounting”; in this case, the search was focused on the occurrence of one or the other term (query link: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/summary/b99fd232-4e25-4691-b1c1-611830e8ef2c-62a07416/relevance/1 (accessed on 16 January 2024)).

- When searching the Scopus database, we used search field tags TITLE-ABS-KEY, which search the title, abstract, and keywords. To find documents that contained an exact phrase, we enclosed the phrase in braces (example for accounting for the environment: {accounting for the environment}); the rest of the procedure was the same as for the WoS database.

- In the next step, we included all keywords in the field of accounting in the search and found the total number of articles where any of the terms appeared; for the WoS and Scopus databases, the total was 10,238 and 12,656 records, respectively.

- Then, we used the export records function.

- In the case of WoS, we exported the records as a plain text file. We chose custom export selections and marked, on export, author(s), title, source, abstract, and keywords; due to the fact that WoS does not allow for exporting more than 1000 records at a time, we exported a total of 11 files.

- In the case of Scopus, we exported the records as a CSV file, etc. As for WoS, we marked, for export purposes, author(s), document title, source title, abstract, author keywords, and indexed keywords; it is possible to export up to 20,000 documents in CSV format, so our export contained only one file.

- Consequently, in the program VOSviewer_1.6.20, we created a map based on exported bibliographic data. We chose this option to create a keyword co-occurrence map; as the type of analysis, we chose the co-occurrence of keywords.

- The overall map creation in VOSviewer_1.6.20 consisted of several phases; maps were created on the basis of bibliographic data (11 plain text files from WoS and 1 CSV file from Scopus) separately for WoS and Scopus (due to the capabilities of the software).

- In the initial phase, we generated a set of all keywords identified by VOSviewer in the data; based on the analysis of the co-occurrence of keywords from WoS data, it was a set of 22,801 keywords, and from Scopus data, it was a set of 10,325 keywords. From the given files, we created a VOSviewer thesaurus file, which was used to merge different variants of a keyword and also to ignore irrelevant terms.

- For example, for the terms corporate responsibility reporting (csr); CSR reporting; corporate social responsibility (‘csr’) reporting; corporate social responsibility (csr) reporting; and corporate social responsibility reporting, the term CSR reporting was used.

- For the terms non financial reporting; non- financial reporting; non-(financial) reporting; non-financial reporting; non-financial reporting (nfr); non-financial reporting; non/financial reporting; and nonfinancial reporting, the term nonfinancial reporting was used.

- Then, we created two keyword co-occurrence maps based on exported bibliographic data and created thesaurus files; the minimum number of occurrences of a keyword was set at five, and the total link strength was at least one. In total, 52 keywords met the threshold for bibliographic data from WoS, and 49 met the threshold for bibliographic data from Scopus.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Interpretation of Research Question 1

- Sustainability accounting as a separate term occurs in articles registered in the WoS database at a number of 323 and, in the Scopus database, at a number of 389.Ultimately, the lower frequency of occurrence of this concept in the identified databases reflects the fact that sustainability is not looked at comprehensively (while maintaining the TBL principle) but in many cases only through an environmental or social sphere.

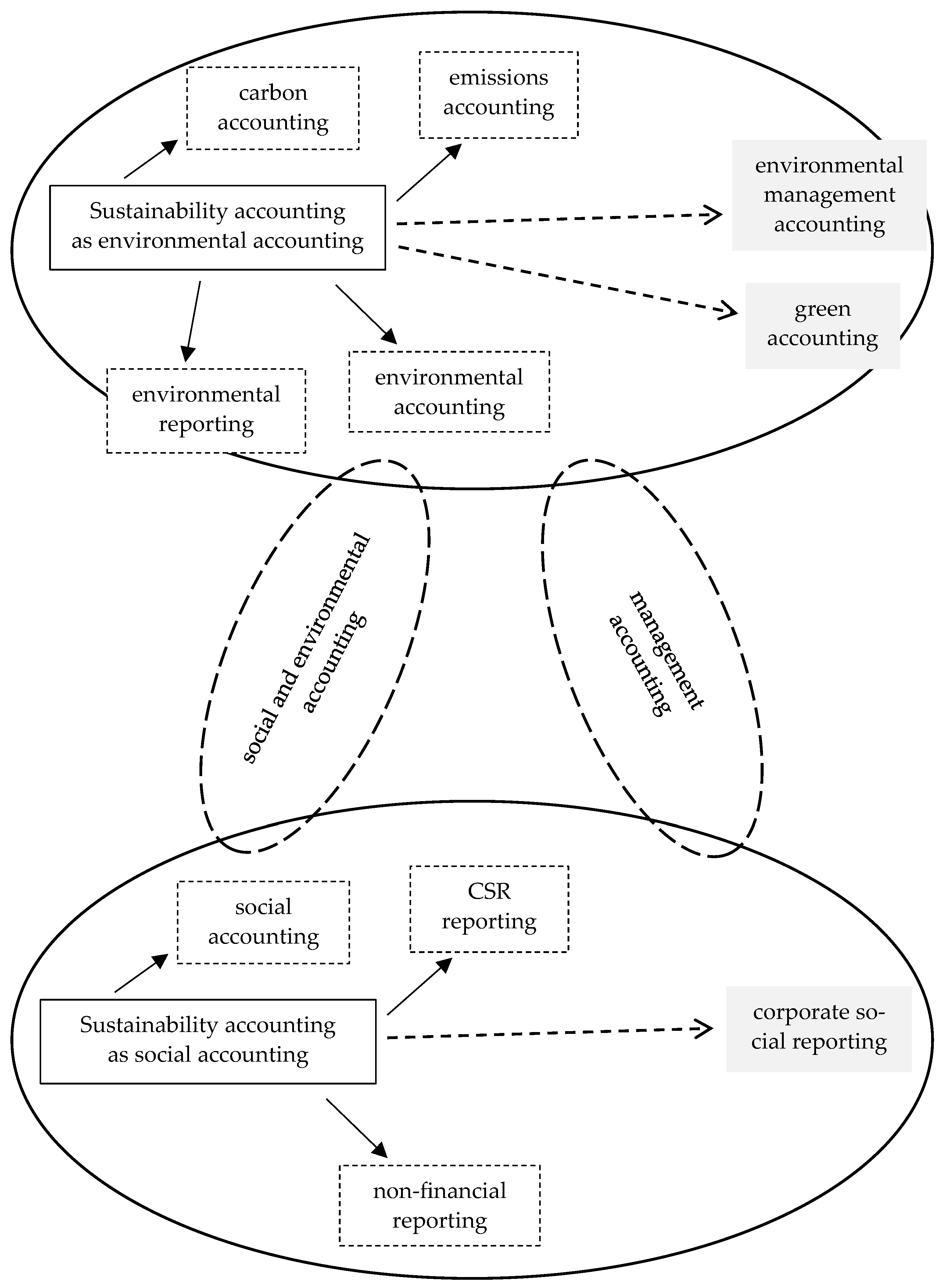

- The term sustainability accounting occurs in different interpretations and their synonyms. With regard to the frequency of occurrence, these are terms such as management accounting, carbon accounting, environmental accounting, social accounting, CSR reporting, environmental reporting, non-financial reporting, and emissions accounting, with a lower incidence (less than 300) of interpretations in the form of environmental management accounting, green accounting, social and environmental accounting, and corporate social reporting.Ultimately, the term sustainability accounting can be seen on two levels, namely environmental and social (Figure 3). Differences in the perception of this concept are related to the individual opinions of the authors themselves (experts from industry and academia) on the meaning and characteristics of the concept of sustainability. The intersection between the environmental and social spheres is social and environmental accounting, which highlights two areas of sustainability, and management accounting, which appears in three basic positions: as a synonym for sustainability accounting, as a traditional tool for the gathering and presenting of financial information to business managers and other stakeholders within an organisation, and as a guideline for businesses in environmental and social fields.

5.2. Interpretation of the Research Question 2

- Sustainability; carbon accounting; governance; ecology (from the red cluster);

- Corporate social responsibility; sustainability reporting; CSR reporting; quality; global reporting initiative; ESG reporting (from the blue cluster);

- Social accounting; social and environmental accounting; ethics; social audits; environmental accounting and reporting (from the sand cluster);

- Environmental accounting; green accounting; water accounting (from the purple cluster);

- Management accounting; corporate sustainability; social and environmental reporting; success; sustainability management; sustainability management accounting; GRI reporting; TBL accounting; economic sustainability (from the green cluster).

- Sustainability; green accounting (from red cluster);

- Environmental accounting; sustainability management accounting (from green cluster);

- Sustainability reporting (from sand cluster);

- Corporate sustainability; sustainability management; TBL accounting (from purple cluster).

5.3. Research Limitations and Contributions of This Study

- Due to the fact that the databases do not include the full texts of the indexed articles, the search results are only sources, where the keywords defined by us in the field of accounting (see Table 6) were found in title, abstract, and in the indexed keywords (author keywords (WoS), Keywords Plus (WoS), keywords (Scopus)). In this way, sources where the keywords we defined were in the full text but were not part of the title, abstract, or indexed keywords of the article could be omitted from the output.

- Not all sources indexed in the databases have listed author keywords (WoS), Keywords Plus (WoS), keywords (Scopus), and abstract.Also, for this reason, there may have been unidentified sources that dealt with keywords as defined by us.

- The time of generating outputs, as the frequency of occurrences of resources containing given keywords, changes over time.

- Defining the term sustainability accounting, its different interpretations, and their synonyms (such as green, environmental, economic, cost, financial, etc.) including the identification of the relationship between sustainability accounting and the different names used for this term.Explanation: Sustainability accounting is an essential part of the future of accounting; it includes the TBL quantification of the company’s activities, products, and services and integrates sustainability metrics into financial reporting. Accountants who want to build a successful career in accounting must understand the difference between sustainability accounting and sustainability reporting. That means communicating a business’s sustainability performance and practices to external stakeholders (London Premier Centre 2023). Similar opinions have also been studied (Schaltegger et al. 2006). According to them, the zenith of accounting and reporting at present is sustainability accounting and reporting, with its conceptual emphasis on accounting for ecosystems and for communities and the consideration of eco-justice, as well as more conventional issues of effectiveness and efficiency. Under this view (Schaltegger et al. 2006), the term sustainability accounting is used to describe new information management and accounting methods that aim to create and provide high-quality information to support a corporation in its movement towards sustainability.Distinguishing the differences between the terms not only arises from the need for accounting practice (Çalışkan 2014; Politzer 2021; ACCA 2024) and the need to implement the concept of sustainability into a company’s strategy (Ameer and Othman 2012; Shad et al. 2019; Breu et al. 2021; Tarnovskaya 2023) but also from understanding the content of the analysed terms, which helps us understand the meaning of the increasing number of reporting regulations, government pressures, international verification, and accounting standards, as well as changing stakeholder strategies and demands. Evidence of this is also found in the findings on perceptions of the expressions of sustainable accounting.

- Emphasising the importance and position of sustainability accounting in the internal and external environment of the company.Explanation: There are three objectives of sustainability accounting (Ozili 2021): The first objective is to prepare accounts concerning organisations’ interactions with society and the natural environment; the second objective of sustainability accounting is to disclose financial and non-financial information about an organisation’s performance in relation to society and the environment; and the third objective is to extend traditional financial accounting to take into account a wide range of monetized information, covering environmental, social, and economic impacts, on which organisational decisions are made. The importance of sustainability accounting and its implications for accountants has been the subject of analysis in several studies (KPMG 2021; Joseph 2023; Low 2023; Westford Uni Online 2023). Schaltegger and Burritt (2010) identified six reasons that may encourage managers to establish an accounting system that provides information for assessing corporate actions on sustainability issues, such as greenwashing; mimicry and industry pressure; legislative pressure, stakeholder pressure, and ensuring the “licence to operate”; self-regulation; corporate responsibility and ethical reasons; and managing a business case for sustainability.Recently, there has been significant legislative pressure, which started to manifest itself, first of all, from 2013 onwards in connection with the adjustment of the reporting of financial and non-financial information. What, for many companies, was initially on a voluntary basis (Non-financial Reporting Directive) is gradually becoming a statutory requirement (the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive). However, this does not mean that other companies will avoid reporting ESG data altogether in the near term. Many of them will be approached in supply chains or when being considered by banks in lending processes (e.g., KPMG 2023).The importance of sustainability accounting is also recognised by many consultancies, such as KPMG, PWC, and EY. Their regular surveys highlight the importance and necessity of linking sustainability to accounting, with the need to consider the interests and requirements of stakeholders, including the challenges that many businesses continually face in this area. As an example, we refer to the following surveys:

- The international accounting firm KPMG releases the 2024 Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Report (Today ESG 2024), which aims to analyse the development of corporate sustainability disclosure and the differences between disclosure and sustainable strategies. KPMG believes that with the development of global regulatory policies, companies need to disclose more environmental, social, and governance-related information. Companies are also recognising that sustainable disclosure will become a tool to improve financial performance. However, most companies still have a gap between sustainable strategy and execution.

- The report “Anchoring ESG in governance” (KPMG 2024), based on in-depth interviews with 50 chief sustainability officers and managers in 10 countries, examines how group sustainability units operate within corporate structures, what makes them successful, and how they plan to develop in the future. It finds that sustainability has become a board-level responsibility but that sustainability-focused organisations are still developing in maturity, including in response to new ESG reporting requirements, such as the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

- KPMG’s report “KPMG ESG Assurance Maturity Index 2023” (Tyson 2023) reveals that as many as 75 percent of companies globally feel they have a long way to go to be ready to have their ESG data assured and meet new regulatory requirements. Those most ready for ESG assurance tend to have boards more engaged on ESG issues, conduct regular ESG training, and have controls in place for ESG data.

- Almost two-thirds (59%) of Slovak companies are unaware that they will be required to collect data and subsequently perform non-financial ESG reporting starting in 2024, according to a representative survey of 130 companies and executives conducted by consultancy RSM (TASR 2023). Only 8% of respondents said they were aware of the new obligation and knew the details. A further 28% say they have heard of the news but do not know the details. “It is important to note that major trading partners such as Germany, France and the Netherlands are already in the process of implementing the directive and there is pressure on suppliers in other countries to consider an ESG strategy even without a legislative framework”.

- The survey from the US audit, tax, and advisory firm KPMG LLP “Addressing the Strategy Execution Gap in Sustainability Reporting” explores addressing the strategy execution gap in sustainability reporting. Speaking on the results and the trends that emerged, KPMG US Climate Data & Technology leader Tegan Keele said (ESG Mena 2024), “Artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies can help organisations gain valuable insights from disparate data and make more informed decisions, but AI and ML are not a silver bullet for sustainability reporting or for setting a strategy that adds value to the business”.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACCA. 2024. Things You Need to Know: Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://www.accaglobal.com/gb/en/student/sa/professional-skills/masterclass-sustainability-reporting.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Ameer, Rashid, and Radiath Othman. 2012. Sustainability Practices and Corporate Financial Performance: A Study Based on the Top Global Corporations. Journal of Business Ethics 108: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Amanda, and Russell Craig. 2010. Using neo-institutionalism to advance social and environmental accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 21: 283–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomeo, Matteo, Martin Bennett, Jan Jaap Bouma, Peter Heydkamp, Peter James, and Teun Wolters. 2000. Environmental management accounting in Europe: Current practice and future potential. European Accounting Review 9: 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, Jan, and Rob Gray. 2001. An account of sustainability: Failure, success and reconceptualization. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 2: 557–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, Ataur R., and Stuart M. Cooper. 2011. The absence of corporate social responsibility reporting in Bangladesh. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 22: 654–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouten, Lies, Patricia Everaert, Luc Van Liedekerke, Lieven De Moor, and Johan Christiaens. 2011. Corporate social responsibility reporting: A comprehensive picture? Accounting Forum 35: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Niamh M., and Doris M. Merkl-Davies. 2014. Rhetoric and argument in social and environmental reporting: The Dirty Laundry case. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 27: 602–33. [Google Scholar]

- Breu, Thomas, Michael Bergöö, Laura Ebneter, Myriam Pham-Truffert, Sabin Bieri, Peter Messerli, Cordula Ott, and Christoph Bader. 2021. Where to begin? Defining national strategies for implementing the 2030 Agenda: The case of Switzerland. Sustainability Science 16: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burritt, Roger L., and Stefan Schaltegger. 2010. Sustainability accounting and reporting: Fad or trend? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 23: 829–46. [Google Scholar]

- Burritt, Roger L., Tobias Hahn, and Stefan Schaltegger. 2004. An integrative framework of environmental management accounting—Consolidating the different approaches of EMA into a common framework and terminology. In Environmental Management Accounting: Informational and Institutional Developments. Edited by Martin Bennett, Jan Jaap Bouma and Teun Wolters. Boston: Kluwer, pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, Concetta, Maria Mazzuca, and Sergio Venturini. 2012. Corporate social reporting in European banks: The effects on a firm’s market value. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 19: 159–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jennifer, and Robin Roberts. 2010. Toward a More Coherent Understanding of the Organization—Society Relationship: A Theoretical Consideration for Social and Environmental Accounting Research. Journal of Business Ethics 97: 651–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M. Peter, Michael B. Overell, and Larelle Chapple. 2011. Environmental Reporting and its Relation to Corporate Environmental Performance. Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business Studies 47: 27–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cormier, Denis, Marie-Josée Ledoux, and Michael Magnan. 2011. The informational contribution of social and environmental disclosures for investors. Management Decision 49: 1276–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışkan, Arzu Özsözgün. 2014. How accounting and accountants may contribute in sustainability? Social Responsibility Journal 10: 246–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagilienė, Lina, and Ruta Nedzinskienė. 2018. An institutional theory perspective on non-financial reporting: The developing Baltic context. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 16: 490–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, Dan S., Oliver Zhen Li, Albert Tsang, and Yong George Yang. 2011. Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review 86: 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, Jesse. 2014. Legitimating the social accounting project: An ethic of accountability. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability, 2nd ed. Edited by Jan Bebbington, Jeffrey Unerman and Brendan O’Dwyer. London: Routledge, pp. 251–65. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, John. 1993. Coming clean: The rise and rise of the corporate environmental report. Business Strategy and the Environment 2: 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, John. 1997. Cannibals with forks. In The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century. Oxford: Capstone Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, John. 1999. Triple bottom-line reporting: Looking for balance. Australian CPA 69: 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency. 1995. An Introduction to Environmental Accounting as a Business Management Tool: Key Concepts and Terms. Washington, DC: Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- ESG Mena. 2024. KPMG Survey: Addressing the Strategy Execution Gap in Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://esgmena.com/2024/02/22/kpmg-survey-addressing-the-strategy-execution-gap-in-sustainability-reporting/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Európska Komisia. 2020. Panorama 71: Konkurencieschopnosť ako podpora udržateľnosti. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sk/newsroom/news/2020/02/02-12-2020-panorama-71-competitiveness-gives-sustainability-a-boost (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Figge, Frank, and Tobias Hahn. 2004. Sustainable Value Added—Measuring corporate contributions to sustainability beyond eco-efficiency. Ecological Economics 48: 173–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Rob. 2000. Current developments and trends in social and environmental auditing, reporting and attestation: A review and comment. International Journal of Auditing 4: 247–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Rob. 2002. The social accounting project and Accounting Organizations and Society Privileging engagement, imaginings, new accountings and pragmatism over critique? Accounting, Organizations and Society 27: 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Rob. 2010. Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Accounting, Organisations and Society 35: 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Rob, and Markus Milne. 2002. Sustainability reporting: Who’s kidding whom? Chartered Accountants Journal of New Zealand 81: 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Rob, Jan Bebbington, and Diane Walters. 1993. Accounting for the Environment. London: Paul Chapman. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Rob, Reza Kouhy, and Simon Lavers. 1995. Corporate social and environmental reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 8: 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- Idowu, Samuel O., Nicholas Capaldi, Liangrong Zu, and Ananda Das Gupta, eds. 2013. Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jankalová, Miriam, and Jana Kurotová. 2020. Sustainability Assessment Using Economic Value Added. Sustainability 12: 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Michael John. 2010. Accounting for the environment: Towards a theoretical perspective for environmental accounting and reporting. Accounting Forum 34: 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Aldeia. 2023. The Rise of Sustainability Accounting: Integrating ESG Factors into Financial Reporting and Decision-Making. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rise-sustainability-accounting-integrating-esg-factors-joseph-aldeia (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- KPMG. 2021. The Growing Pursuit of Sustainability. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2021/04/the-growing-pursuit-of-sustainability.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- KPMG. 2023. Available online: https://kpmg.com/sk/sk/home/media/press-releases/2023/01/property-lending-barometer-2022.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- KPMG. 2024. Anchoring ESG in Governance. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2024/02/anchoring-esg-in-governance.html (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- La Torre, Matteo, Lana Sabelfeld, Marita Blomkvist, Lara Tarquinio, and John C. Dumay. 2018. Harmonising non-financial reporting regulation in Europe: Practical forces and projections for future research. Meditari Accountancy Research 26: 598–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, Geoff. 2005. Sustainability accounting—A brief history and conceptual framework. Accounting Forum 29: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrinaga-Gonzalez, Carlos, and Jan Bebbington. 2001. Accounting change or institutional appropriation? A case study of the implementation of environmental accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 12: 269–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, Glen. 1999. Disclosing new worlds: A role for social and environmental accounting and auditing. Accounting, Organizations and Society 24: 217–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, Sumit K., and Umesh Sharma. 2019 Sustainability accounting and reporting: Recent perspectives and an agenda for further research. Pacific Accounting Review 31: 309–12.

- Lodhia, Sumit K., ed. 2018. Mining and sustainable development. In Mining and Sustainable Development: Current Issues. London: Routledge, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- London Premier Centre. 2023. Sustainable Accounting: Measuring Environmental and Social Impact. Available online: https://www.lpcentre.com/articles/sustainable-accounting-measuring-environmental-and-social-impact (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Low, Ryan. 2023. The Role of Accounting in Sustainable Business Practices. Available online: https://www.wlp.com.sg/the-role-of-accounting-in-sustainable-business-practices/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Mathews, Martin Reginald. 1984. A suggested classification for social accounting research. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 3: 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, Martin Reginald. 1993. Socially Responsible Accounting. London: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, Markus J., Helen Tregidga, and Sara Walton. 2009. Words not actions! The ideological role of sustainable development reporting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 22: 1211–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, Vinal, Umesh Sharma, and Mary Low. 2014. Management accountants’ perception of their role in accounting for sustainable development: An exploratory study. Pacific Accounting Review 26: 112–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ociti, Innocent. 2023. Correlation between Sustainability Practices and Financial Performance in Companies across Various Industries. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/correlation-between-sustainability-practices-financial-innocent-ociti (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Ozili, Peterson K. 2021. Sustainability Accounting. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3803384 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Özmen, Serkan Y. 2013. Environmental Accounting. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Samuel O. Idowu, Nicholas Capaldi, Liangrong Zu and Ananda Das Gupta. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 961–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pahuja, Shuchi. 2013. Environmentally Sensitive Accounting. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Samuel O. Idowu, Nicholas Capaldi, Liangrong Zu and Ananda Das Gupta. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 1033–39. [Google Scholar]

- Perkiss, Stephanie, and Dale Tweedie. 2017. Social accounting into action: Religion as ‘moral source’. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37: 174–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, Maria. 2021. Sustainability Accountants: What Do They Do? Available online: https://www.fm-magazine.com/issues/2021/sep/sustainability-accountants.html (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Protin, Philippe, Nathalie Gonthier-Besacier, Charlotte Disle, Frédéric Bertrand, and Stéphane Périer. 2014. L’information non financière. Clarification d’un concept en vogue. Revue française de gestion 5: 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rahi, ABM Fazle, Ruzlin Akter, and Jeaneth Johansson. 2022. Do sustainability practices influence financial performance? Evidence from the Nordic financial industry. Accounting Research Journal 35: 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retolaza, José-Luis, Leire San-Jose, and Maite Ruíz-Roqueñi. 2016. Social Accounting for Sustainability: Monetizing the Social Value. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay, Arunaditya. 2004. Environmental reporting by Indian corporations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 11: 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAP. 2024a. To Profit from Sustainability, Be Resolute. Available online: https://www.sap.com/insights/research/to-profit-from-sustainability-be-resolute.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- SAP. 2024b. What Experience Says About Sustainability. Available online: https://www.sap.com/sk/insights/research/what-experience-says-about-sustainability.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- SAP. 2024c. Sustainability’s Role in Business Performance. Available online: https://www.sap.com/sk/insights/research/sustainabilitys-role-in-business-performance.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- SAP. 2024d. The Link between Sustainability and Business Performance. Available online: https://www.sap.com/sk/insights/research/the-link-between-sustainability-and-business-performance.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Roger L. Burritt. 2000. Contemporary Environmental Accounting: Issues, Concepts and Practice. Scheffield: Greenleaf Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Roger L. Burritt. 2006. Corporate sustainability accounting. A Catchphrase for Compliant Corporations or a Business Decision Support for Sustainability Leaders? In Sustainability Accounting and Reporting. Edited by Stefan Schaltegger, Martin Bennett and Roger Burritt. 21 vols, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, and Roger L. Burritt. 2010. Sustainability accounting for companies: Catchphrase or decision support for business leaders? Journal of World Business 45: 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, Stefan, Martin Bennett, and Roger Burritt. 2006. Sustainability Accounting and Reporting: Development, Linkages and Reflection. An Introduction. In Sustainability Accounting and Reporting. Edited by Stefan Schaltegger, Martin Bennett and Roger Burritt. 21 vols, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shad, Kashif, Fong-Woon Lai, Jiri Jaromir Klemeš, and Chuah Lai Fatt. 2019. Integrating Sustainability Reporting into Enterprise Risk Management and its Relationship with Business Performance: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Cleaner Production 208: 415–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Umesh. 2013. Lessons from the global financial crisis: Bringing neoclassical and Buddhist economics theories together to progress global business decision making in the 21st century. International Journal of Critical Accounting 5: 250–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitnikov, Catalina Soriana. 2013. Triple Bottom Line. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Samuel O. Idowu, Nicholas Capaldi, Liangrong Zu and Ananda Das Gupta. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 2558–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sotorrío, Ladislao Luna, and José Luis Fernández Sánchez. 2010. Corporate social reporting for different audiences: The case of multinational corporations in Spain. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 17: 272–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolowy, Hervé, and Luc Paugam. 2018. The expansion of non-financial reporting: An exploratory study. Accounting and Business Research 48: 525–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnovskaya, Veronika. 2023. Sustainability as the Source of Competitive Advantage. How Sustainable is it? In Creating a Sustainable Competitive Position: Ethical Challenges for International Firms (International Business and Management, Volume 37). Edited by Pervez N. Ghauri, Ulf Elg and Sara Melén Hånell. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing, pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tähtinen, Johanna. 2018. Sustainability Reporting Will Create Long-Term Business and Investor Value. Available online: https://www.ifac.org/knowledge-gateway/discussion/sustainability-reporting-will-create-long-term-business-and-investor-value (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- TASR. 2023. Firmy čaká nová povinnosť vykonávať ESG reporting, väčšina o nej nevie. Available online: https://www.teraz.sk/import/firmy-caka-nova-povinnost-vykonava/718954-clanok.html (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Thomson, Ian. 2007. Mapping the terrain of sustainability accounting. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability. Edited by Jeffrey Unerman, Jan Bebbington and Brendan O’Dwyer. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Today ESG. 2024. KPMG Releases 2024 Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Report. Available online: https://www.todayesg.com/kpmg-corporate-sustainability-disclosure-report/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Torrecchia, Patrizia. 2013. Social Accounting. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Samuel O. Idowu, Nicholas Capaldi, Liangrong Zu and Ananda Das Gupta. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 2167–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson, Jim. 2023. 75% of Companies Unprepared for Coming ESG Audits: KPMG. Available online: https://www.cfodive.com/news/75-percent-companies-unprepared-coming-esg-audits-kpmg-SEC-sustainability-accounting/694839/ (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Westford Uni Online. 2023. Sustainable Accounting Practices: A Blueprint for Next Generation. Available online: https://www.westfordonline.com/blogs/importance-of-sustainable-accounting-practices/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Wood, Richard, Konstantin Stadler, Tatyana Bulavskaya, Stephan Lutter, Stefan Giljum, Arjan De Koning, Jeroen Kuenen, Helmut Schütz, José Acosta-Fernández, Arkaitz Usubiaga, and et al. 2015. Global Sustainability Accounting—Developing EXIOBASE for Multi-Regional Footprint Analysis. Sustainability 7: 138–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongvanich, Kittiya, and James Guthrie. 2006. An extended performance reporting framework for social and environmental accounting. Business Strategy and the Environment 15: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvezdov, Dimitar, and Stefan Schaltegger. 2013. Sustainability Accounting. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. Edited by Samuel O. Idowu, Nicholas Capaldi, Liangrong Zu and Ananda Das Gupta. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 2363–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zyznarska-Dworczak, Beata. 2020. Sustainability Accounting—Cognitive and Conceptual Approach. Sustainability 12: 9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interpretation of Sustainability Accounting | Use Of Sustainability Accounting |

|---|---|

| It is an illusion and buzzword | Window dressing, “green-washing” |

| Broad umbrella term | Window dressing or expression of ignorance |

| Precise overarching measurement approach | One measure covering all aspects of sustainability |

| Process developing a set of pragmatic information management tools and information | Identification of relevant sustainability issues of the company, overall performance tracking, and measurement with respect to the specific characteristics of relevant sustainability issues |

| Approach to Sustainability Accounting | Author | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| environmental accounting | Larrinaga-Gonzalez and Bebbington (2001) | Environmental accounting can be mobilized as a means of encouraging organisations to change in ways that will reduce their unsustainability (this position is described as “organisational change”). Environmental accounting is considered in the context of the environmental agenda and as a part of the process of enabling these organisational changes. |

| Lamberton (2005) | According to Lamberton (2005), environmental accounting research has focused considerable attention on the valuation of environmental assets, liabilities, and costs in an attempt to account for the environment, using generally accepted accounting principles. | |

| Jones (2010) | According to Jones (2010), environmental accounting means the development and operationalisation of an accounting system to measure the environment. Environmental reporting means the reporting of environment accounting to external stakeholders. The authors developed a multilayered theoretical model to underpin environmental accounting and reporting. | |

| environmental reporting | Gray et al. (1995) | Gray et al. (1995) generally consider “environmental reporting and disclosure” to be one facet of social reporting and disclosure. |

| Sahay (2004) | Environmental reporting has become a sub-division of the larger area of corporate social reporting. According to Sahay (2004), it is a method of communicating environmental performance. | |

| Clarkson et al. (2011) | Clarkson et al. (2011) analyse environmental reporting and its relation to corporate environmental performance. The authors consider “environmental reporting” to be environmental disclosures (information). | |

| social accounting | Mathews (1984) | Mathews (1984) distinguishes four categories of social accounting. 1. Social responsibility accounting (SRA): Social responsibility accounting refers to disclosures of financial and nonfinancial, as well as quantitative and qualitative, information about the activities of an enterprise. This area also includes employee reports (ERs) and human resource accounting (HRA). Alternative terms in common use are social responsibility disclosures and corporate social reporting. 2. Total impact accounting (TIA): This term is used here to refer to the aggregate effect of the organisation on the environment. To establish this effect, it is necessary to measure both positive and negative externalities. Because of the origins of this area, it is often referred to as cost benefit analysis (CBA) or social accounting (thereby confusing the use of that term) and social audit. 3. Socio-economic accounting (SEA): Socioeconomic accounting is the process of evaluating publicly funded activities, using both financial and nonfinancial quantification. The entire activity is to be evaluated, with a view of making judgments about the value of expenditure undertaken in relation to the outcomes achieved. 4. Social indicators accounting (SIA): The term social indicators accounting is used to describe the measurement of macro social events, in terms of setting objectives and assessing the degree to which these are attained. The outcomes of this analysis will be of interest to national policy makers. |

| Mathews (1993) | According to Mathews (1993), accounting for the organisation’s social impact is variously referred to as social accounting, social responsibility accounting, and, here, socially responsible accounting. Social accounting is concerned with the preparation and presentation of “accounts”—not necessarily financial accounts—of an organisation’s interaction with the community, environment, employees, and consumers. | |

| Dillard (2014) | According to Dillard (2014), the purpose of social accounting is grounded in the responsibility of organisations to act in the public’s interest. | |

| Retolaza et al. (2016) | Retolaza et al. (2016) assume the fact that value generated or subtracted by organisations for their stakeholders is not just financial but also social, environmental, and emotional, at least. Social accounting is a system that can enable social value to be objectified, valued, and compared so that different organisations in particular and stakeholders can manage their actions in a way conducive to the optimizing of that value for the entire society in which organisations operate. | |

| Perkiss and Tweedie (2017) | Perkiss and Tweedie (2017) use the term social and environmental accounting, or social accounting, to broadly refer to “accounts” that extend beyond the conventional financial or economic focus. Hence, social accounting includes practices like social reporting, sustainability reporting, corporate social responsibility reporting, stakeholder dialogue reporting, and environmental reports. The paper analyses, and responds to, one aspect of perceived failures of social accounting to make societies more sustainable. | |

| social and environmental accounting | Ball and Craig (2010) | Ball and Craig (2010) assume the fact that a neo-institutional theory can increase the understanding of an organisation’s general response to social and environmental issues and social activism. The purpose is to advance normative perspectives of social and environmental accounting. |

| Cormier et al. (2011) | According to Cormier et al. (2011), social and environmental accounting is interpreted as social and environmental disclosures for investors. Social and environmental initiatives and activities are a part of a corporation’s corporate social responsibility. | |

| corporate social reporting (corporate social disclosure, social reporting, social report) | Gray et al. (1995) | According to Gray et al. (1995), corporate social and environmental reporting has many virtual synonyms, including corporate social (and environmental) disclosure, social responsibility disclosure and reporting, and even social audit. The principal terms used in their paper are corporate social reporting and corporate social disclosure. |

| Sotorrío and Sánchez (2010) | According to Sotorrío and Sánchez (2010), corporate social disclosure or reporting covers a broad and diverse array of matters, including product information, the environmental impact of corporate operations, employment practices and relations, and supplier and customer interactions. | |

| Carnevale et al. (2012) | Carnevale et al. (2012) use the term social report, which is probably the most important and exhaustive document through which the company shows its commitment to CSR. | |

| Brennan and Merkl-Davies (2014) | Brennan and Merkl-Davies (2014) use the term corporate social and environmental reporting as a means of demonstrating that an organisation has realigned its practices, policies, and performance in line with the expectations of organisational audiences (retrospective focus). | |

| corporate social responsibility reporting | Bouten et al. (2011) | Corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting is interpreted as an important aspect of social and environmental accountability and as “comprehensive reporting”, which requires companies to disclose three types of information for each disclosed CSR item: (i) vision and goals, (ii) management approach, and (iii) performance indicators. |

| Belal and Cooper (2011) | According to Belal and Cooper (2011), organisations use CSR reporting to legitimize their relationship with society and various stakeholders. CSR reporting in the context of a lack of disclosure on three particular eco-justice issues includes child labour, equal opportunities, and poverty alleviation. | |

| Dhaliwal et al. (2011) | Dhaliwal et al. (2011) find that firms with a high cost of equity capital in the previous year tend to initiate a disclosure of CSR activities in the current year and that initiating firms with superior social responsibility performance enjoy a subsequent reduction in the cost of equity capital. | |

| non-financial reporting | Stolowy and Paugam (2018) | Stolowy and Paugam (2018) define “non-financial reporting” (NFR) and show that the concept of NFR involves dual heterogeneity: heterogeneity in the definitions of the underlying concepts and heterogeneity in the type of channels used for reporting non-financial information. They acknowledge the diversity in the terminology used to refer to this type of reporting, which is interchangeably called “non-financial information”, “non-financial reporting” or a “non-financial statement”. According to Protin et al. (2014), the following terms are used, in decreasing order of frequency: non-financial information, non-financial reporting, non-financial disclosure, and extra-financial information/disclosure/reporting. Stolowy and Paugam discuss the definitions of the main concepts relating to NFR (e.g., sustainability reporting, CSR reporting, integrated reporting). |

| La Torre et al. (2018) | La Torre et al. (2018) consider non-financial reporting in the context of European Union Directive 2014/95 on non-financial and diversity information. | |

| Dagilienė and Nedzinskienė (2018) | Information disclosure is not only a presentation of significant financial information to investors but also sustainable information disclosure to various stakeholders. Dagilienė and Nedzinskienė explore the impact of different institutional factors on non-financial reporting. |

| Author | Term of Sustainability Accounting | Approach to Sustainability Accounting |

|---|---|---|

| Gray (2002) | social accounting | Social accounting is used here as a generic term for convenience to cover all forms of “accounts which go beyond the economic” and for all the different labels under which it appears—social responsibility accounting, social audits, corporate social reporting, employee and employment reporting, stakeholder dialogue reporting, and environmental accounting and reporting. |

| Burritt and Schaltegger (2010) | corporate sustainability accounting | From a critical perspective, corporate sustainability accounting is the cause and source of corporate sustainability problems. From a management-oriented path, corporate sustainability accounting is a set of tools that provides help for managers dealing with different decisions. |

| Wood et al. (2015) | global sustainability accounting | This is a system to operationalize a globally integrated accounting framework within the SEEA guidelines (System of Environmental-Economic Accounts) and to integrate accounting frameworks for the global mapping of environmental, economic, and social impacts. |

| Schaltegger and Burritt (2006) | sustainability accounting | Sustainability accounting describes a subset of accounting that deals with activities, methods, and systems to record, analyse, and report the following: first, environmentally and socially induced financial impacts; second, the ecological and social impacts of a defined economic system (e.g., the company, production site, nation, etc.); third, and perhaps most important, the interactions and linkages between social, environmental, and economic issues constituting the three dimensions of sustainability. |

| Chen and Roberts (2010) | social and environmental accounting | By applying these applicable theoretical frameworks to social and environmental accounting, it is possible to examine how firms manage their image when a social expectation is assumed and the targeted audience is not explicitly named (legitimacy theory); the adoption of a specific corporation structure, system, program, or practice that is commonly implemented by similar organisations (institutional theory); the dynamic interactions between two competing or complementary organisations (resource dependence theory); and unexpected social or environmental activities undertaken by corporations (stakeholder theory). There are two theoretical considerations that are important for future social and environmental accounting research. First, it must be acknowledged that some business entities initiate social activities based on direct interactions with stakeholders, whereas others may also undertake similar activities to manage their societal levels of legitimacy. Second, from analysing the perspectives of legitimacy theory, institutional theory, resource dependence theory, and stakeholder theory, it is possible to reach compatible interpretations of business social phenomena. |

| Lehman (1999) | social and environmental accounting | Social and environmental accounting is used as two interlocking social mechanisms that can be used to engage the hegemonic and destructive forces of the capitalist relations of production. For example, social accounting has been developed to measure and verify the effects of, among other things, the costs of plant closure and the levels of emission, waste, and pollution. |

| Term of Accounting | Synonyms | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| accounting for the environment | environmentally sensitive accounting | --- |

| environmentally sensitive accounting | accounting for the environment; environmental financial accounting; environmental management accounting; green accounting; natural resource accounting | “Accounting with environmental considerations”. (Pahuja 2013) |

| green accounting | environmental accounting; environmentally sensitive accounting | --- |

| environmental accounting | ecological accounting; green accounting; sustainability accounting | “A branch of accounting that deals with (i) activities, methods and systems, (ii) recording, analysis and reporting, (iii) environmentally induced financial impacts and ecological impacts of a defined economic system”. (Schaltegger and Burritt 2000) |

| social and environmental accounting | social accounting; sustainability accounting | --- |

| social accounting | corporate social reporting; corporate social responsibility reporting; nonfinancial reporting; social and environmental accounting; sustainability accounting; triple bottom line accounting | “A tool of Corporate Social Responsibility: the identification and recording of an entity’s activities in terms of its social responsibility”. (Torrecchia 2013) |

| triple bottom line accounting | social accounting | “Triple bottom line accounting widens the conventional reporting structure to include ecological and social performance, in addition to economic performance”. (Sitnikov 2013) |

| sustainability accounting | management accounting; social and environmental accounting; sustainability management accounting | “Sustainability accounting entails systems, methods, and processes of creating sustainability information for transparency, accountability, and decision making purposes. This includes the identification of relevant sustainability issues of the company, the definition of indicators and measures, data collection, overall performance tracking and measurement, as well as the communication with to internal and external information recipients”. (Zvezdov and Schaltegger 2013) |

| Core Element | Description |

|---|---|

| sustainability information generation and management | The aspects of information generation and management to be considered include the following: Who within the company is involved with the process of sustainability accounting? What kind of sustainability information is generated? Why is the sustainability information generated? Who uses sustainability information? How are data collection and information creation organized? What sustainability management accounting methods are applied? |

| sustainability management control | The central task is to “translate” strategies into strategic management action. One practice-oriented concept of sustainability management control is framed within the structure of the sustainability balanced scorecard (SBSC), which provides a framework for organizing sustainability management control and its orientation toward the effective and efficient implementation of a company’s strategy. This allows for distinguishing between the following orientations: finance-oriented sustainability management control; market-oriented sustainability management control; process-oriented sustainability management control; knowledge- and learning-oriented sustainability management control; and non-market-oriented sustainability management control. |

| sustainability reporting | Sustainability reporting encompasses formal and official corporate communication, which provides information about corporate sustainability issues. This includes, in particular, information about the social, environmental, and economic performance and the relationships between these aspects of corporate performance. |

| Keywords in the Field of Sustainability Accounting | First Mention in WoS | Number in WoS | First Mention in Scopus | Number in Scopus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| accounting for the environment | 1991 | 30 | 1975 | 38 |

| carbon accounting | 1995 | 1277 | 1990 | 1561 |

| corporate social reporting | 1976 | 108 | 1977 | 162 |

| corporate sustainability accounting | 2006 | 3 | 2006 | 4 |

| corporate social responsibility reporting or CSR reporting | 2005 | 848 | 2004 | 927 |

| ecological accounting | 1997 | 65 | 1995 | 86 |

| economic and environmental accounting | 2000 | 10 | 2000 | 12 |

| emissions accounting | 1993 | 491 | 1985 | 404 |

| employee reporting | 1981 | 18 | 1977 | 25 |

| employment reporting | 2017 | 4 | 2020 | 1 |

| environmental accounting | 1987 | 1189 | 1976 | 1618 |

| environmental accounting and reporting | 1993 | 38 | 1991 | 58 |

| environmental financial accounting | 2009 | 5 | 2010 | 6 |

| environmental management accounting | 2003 | 276 | 2000 | 314 |

| environmental reporting | 1979 | 715 | 1976 | 1118 |

| environmentally sensitive accounting | 0 | 2022 | 1 | |

| global sustainability accounting | 2015 | 1 | 2015 | 1 |

| green accounting | 1992 | 210 | 1992 | 277 |

| management accounting | 1951 | 3634 | 1954 | 4327 |

| natural resource accounting | 1986 | 45 | 1986 | 74 |

| nonfinancial reporting or non-financial reporting | 2003 | 542 | 1999 | 656 |

| social accounting | 1923 | 1181 | 1946 | 1567 |

| social and environmental accounting | 1992 | 201 | 1992 | 325 |

| social audits | 1978 | 60 | 1977 | 102 |

| social responsibility accounting | 1976 | 27 | 1982 | 29 |

| stakeholder dialogue reporting | 0 | 0 | ||

| sustainability accounting | 2003 | 323 | 1999 | 389 |

| sustainability management accounting | 2006 | 26 | 2006 | 29 |

| sustainability reporting and accounting | 2008 | 5 | 2008 | 5 |

| triple bottom line accounting or TBL accounting | 2004 | 25 | 2000 | 27 |

| WoS Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| corporate social responsibility | 1086 | 1384 |

| management accounting | 877 | 126 |

| sustainability | 803 | 945 |

| environmental accounting | 627 | 321 |

| carbon accounting | 416 | 64 |

| governance | 394 | 594 |

| sustainability reporting | 333 | 580 |

| social accounting matrix | 308 | 9 |

| csr reporting | 306 | 454 |

| quality | 265 | 383 |

| nonfinancial reporting | 262 | 334 |

| environmental reporting | 234 | 198 |

| social accounting | 158 | 123 |

| global reporting initiative | 141 | 276 |

| sustainability accounting | 117 | 142 |

| green accounting | 104 | 71 |

| social and environmental accounting | 93 | 109 |

| social reporting | 88 | 117 |

| corporate sustainability | 83 | 141 |

| ethics | 74 | 103 |

| social and environmental reporting | 52 | 66 |

| competitive advantage | 46 | 36 |

| environmental | 45 | 78 |

| social | 39 | 68 |

| environmental sustainability | 38 | 37 |

| success | 34 | 16 |

| emissions accounting | 33 | 7 |

| business ethics | 27 | 32 |

| ecology | 27 | 21 |

| ecological accounting | 24 | 10 |

| social audits | 20 | 18 |

| competitiveness | 18 | 15 |

| natural resources accounting | 15 | 3 |

| sustainability management | 14 | 24 |

| water accounting | 13 | 13 |

| social sustainability | 12 | 14 |

| esg reporting | 11 | 28 |

| social responsibility accounting | 11 | 4 |

| voluntary reporting | 11 | 24 |

| corporate environmental responsibility | 10 | 22 |

| social responsibility reporting | 10 | 14 |

| sustainability accounting and reporting | 9 | 13 |

| environmental accounting and reporting | 8 | 12 |

| social and environmental accounting and reporting | 8 | 8 |

| ethical decision making | 7 | 9 |

| sustainability management accounting | 7 | 7 |

| environmental audit | 6 | 5 |

| gri reporting | 6 | 15 |

| tbl accounting | 6 | 9 |

| biodiversity reporting | 5 | 7 |

| economic sustainability | 5 | 5 |

| ecosystem accounting | 5 | 4 |

| Scopus Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| management accounting | 1583 | 64 |

| environmental accounting | 753 | 277 |

| carbon accounting | 549 | 24 |

| environmental reporting | 546 | 200 |

| corporate social responsibility | 482 | 325 |

| social accounting matrix | 438 | 8 |

| sustainability | 436 | 357 |

| social accounting | 392 | 111 |

| green accounting | 210 | 89 |

| ecology | 144 | 117 |

| social reporting | 122 | 95 |

| global reporting initiative | 96 | 148 |

| sustainability reporting | 77 | 147 |

| environmental audit | 75 | 62 |

| ethics | 63 | 53 |

| csr reporting | 62 | 51 |

| corporate sustainability | 50 | 81 |

| natural resource accounting | 50 | 43 |

| social and environmental accounting | 49 | 31 |

| sustainability accounting | 45 | 77 |

| business ethics | 42 | 45 |

| social and environmental reporting | 37 | 32 |

| ecological accounting | 34 | 13 |

| competitive advantage | 32 | 26 |

| governance | 28 | 8 |

| social audits | 27 | 15 |

| nonfinancial reporting | 26 | 21 |

| sustainability management | 23 | 23 |

| water accounting | 18 | 30 |

| economic sustainability | 17 | 17 |

| competitiveness | 16 | 17 |

| sustainability management accounting | 16 | 27 |

| quality | 15 | 9 |

| ecological social accounting matrix | 12 | 12 |

| tbl accounting | 12 | 26 |

| corporate environmental responsibility | 11 | 18 |

| emissions accounting | 11 | 7 |

| social and ecological accounting matrix | 10 | 5 |

| tbl reporting | 10 | 20 |

| employee reporting | 9 | 7 |

| accounting for sustainability | 6 | 6 |

| environmental social accounting matrix | 6 | 1 |

| social and environmental accounting and reporting | 6 | 12 |

| voluntary reporting | 6 | 6 |

| environmental accounting and reporting | 5 | 5 |

| environmental and ethical reporting | 5 | 5 |

| ethical responsibility | 5 | 10 |

| social management accounting | 5 | 10 |

| stakeholder reporting | 5 | 5 |

| Cluster | WoS Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster RED (14 items) | sustainability | 803 | 945 |

| carbon accounting | 416 | 64 | |

| governance | 394 | 594 | |

| social accounting matrix | 308 | 9 | |

| competitive advantage | 46 | 36 | |

| environmental | 45 | 78 | |

| social | 39 | 68 | |

| environmental sustainability | 38 | 37 | |

| emissions accounting | 33 | 7 | |

| ecology | 27 | 21 | |

| ecological accounting | 24 | 10 | |

| competitiveness | 18 | 15 | |

| social sustainability | 12 | 14 | |

| sustainability accounting and reporting | 9 | 13 | |

| Cluster GREEN (13 items) | management accounting | 877 | 126 |

| environmental reporting | 234 | 198 | |

| sustainability accounting | 117 | 142 | |

| corporate sustainability | 83 | 141 | |

| social and environmental reporting | 52 | 66 | |

| success | 34 | 16 | |

| sustainability management | 14 | 24 | |

| sustainability management accounting | 7 | 7 | |

| gri reporting | 6 | 15 | |

| environmental audit | 6 | 5 | |

| tbl accounting | 6 | 9 | |

| biodiversity reporting | 5 | 7 | |

| economic sustainability | 5 | 5 | |

| Cluster BLUE (10 items) | corporate social responsibility | 1086 | 1384 |

| sustainability reporting | 333 | 580 | |

| csr reporting | 306 | 454 | |

| quality | 265 | 383 | |

| nonfinancial reporting | 262 | 334 | |

| global reporting initiative | 141 | 276 | |

| esg reporting | 11 | 28 | |

| social responsibility accounting | 11 | 4 | |

| social responsibility reporting | 10 | 14 | |

| social and environmental accounting and reporting | 8 | 8 | |

| Cluster SAND (10 items) | social accounting | 158 | 123 |

| social and environmental accounting | 93 | 109 | |

| social reporting | 88 | 117 | |

| ethics | 74 | 103 | |

| business ethics | 27 | 32 | |

| social audits | 20 | 18 | |

| voluntary reporting | 11 | 24 | |

| corporate environmental responsibility | 10 | 22 | |

| environmental accounting and reporting | 8 | 12 | |

| ethical decision making | 7 | 9 | |

| Cluster PURPLE (5 items) | environmental accounting | 627 | 321 |

| green accounting | 104 | 71 | |

| natural resources accounting | 15 | 3 | |

| water accounting | 13 | 13 | |

| ecosystem accounting | 5 | 4 |

| Cluster | Scopus Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster RED (11 items) | carbon accounting | 549 | 24 |

| sustainability | 436 | 357 | |

| green accounting | 210 | 89 | |

| ecology | 144 | 117 | |

| natural resource accounting | 50 | 43 | |

| ecological accounting | 34 | 13 | |

| water accounting | 18 | 30 | |

| competitiveness | 16 | 17 | |

| ecological social accounting matrix | 12 | 12 | |

| emissions accounting | 11 | 7 | |

| social and ecological accounting matrix | 10 | 5 | |

| Cluster GREEN (10 items) | management accounting | 1583 | 64 |

| environmental accounting | 753 | 277 | |

| social accounting matrix | 438 | 8 | |

| csr reporting | 62 | 51 | |

| competitive advantage | 32 | 26 | |

| sustainability management accounting | 16 | 27 | |

| quality | 15 | 9 | |

| environmental social accounting matrix | 6 | 1 | |

| social management accounting | 5 | 10 | |

| environmental accounting and reporting | 5 | 5 | |

| Cluster BLUE (8 items) | environmental reporting | 546 | 200 |

| social reporting | 122 | 95 | |

| environmental audit | 75 | 62 | |

| ethics | 63 | 53 | |

| social and environmental reporting | 37 | 32 | |

| governance | 28 | 8 | |

| employee reporting | 9 | 7 | |

| voluntary reporting | 6 | 6 | |

| Cluster SAND (8 items) | corporate social responsibility | 482 | 325 |

| global reporting initiative | 96 | 148 | |

| sustainability reporting | 77 | 147 | |

| nonfinancial reporting | 26 | 21 | |

| corporate environmental responsibility | 11 | 18 | |

| social and environmental accounting and reporting | 6 | 12 | |

| ethical responsibility | 5 | 10 | |

| stakeholder reporting | 5 | 5 | |

| Cluster PURPLE (7 items) | corporate sustainability | 50 | 81 |

| social and environmental accounting | 49 | 31 | |

| sustainability accounting | 45 | 77 | |

| sustainability management | 23 | 23 | |

| tbl accounting | 12 | 26 | |

| tbl reporting | 10 | 20 | |

| accounting for sustainability | 6 | 6 | |

| Cluster BRIGHT CERULEAN (5 items) | social accounting | 392 | 111 |

| business ethics | 42 | 45 | |

| social audits | 27 | 15 | |

| economic sustainability | 17 | 17 | |

| environmental and ethical reporting | 5 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jankalová, M.; Jankal, R. Review of Sustainability Accounting Terms. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070137

Jankalová M, Jankal R. Review of Sustainability Accounting Terms. Administrative Sciences. 2024; 14(7):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070137

Chicago/Turabian StyleJankalová, Miriam, and Radoslav Jankal. 2024. "Review of Sustainability Accounting Terms" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 7: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070137

APA StyleJankalová, M., & Jankal, R. (2024). Review of Sustainability Accounting Terms. Administrative Sciences, 14(7), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14070137