Abstract

This study examines how performance pressure influences the complex relationships between job autonomy and critical employee outcomes in contemporary organizations. Specifically, we investigate the relationships between employees’ job autonomy, work engagement, and innovative behavior, while testing the moderating effects of performance pressure perceived within teams. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory and the Job Demand–Resource Model, this research explores the dynamic tension between autonomy and performance demands in organizational settings. Using a two-wave survey design to prevent common method bias, data were collected from 485 employees across diverse organizations in South Korea, representing various industries and organizational levels. The results revealed that job autonomy positively impacts both work engagement and innovative behavior, supporting the fundamental role of autonomy in employee motivation and performance. More importantly, performance pressure perceived within teams had significant moderating effects, weakening the positive relationships between job autonomy and work engagement and innovative behavior. The results of simple slope analyses further confirmed these interaction effects, demonstrating that the benefits of job autonomy were consistently diminished under conditions of high performance pressure. These findings contribute to the organizational behavior and human resource management literature by demonstrating how performance pressure within teams can systematically constrain the benefits of job autonomy in contemporary work environments. For practitioners, our results suggest that organizations should enhance employees’ job autonomy while carefully managing performance pressure within team contexts. To optimize organizational effectiveness, organizations should balance autonomous decision-making with performance expectations, fostering immediate outcomes (work engagement) and long-term capabilities (innovative behavior) in an increasingly competitive business environment.

1. Introduction

In an era of unprecedented organizational change, sustainable human resource management has emerged as a critical paradigm for organizational success and longevity. Organizations must not only respond flexibly to technological, economic, governmental, and environmental changes but also ensure that their human resource practices support long-term employee development and organizational sustainability. Recent research has emphasized that building sustainable employee–organization relationships is crucial in organizational development, particularly in promoting innovative behavior and maintaining employee engagement (Yu et al., 2018).

The challenge lies in balancing the increasing pressure for immediate performance with sustainable human resource practices. While organizations need to maintain competitiveness, excessive performance pressure may undermine long-term sustainability by affecting employee well-being and innovation capacity. In this context, job autonomy has emerged as a crucial factor in fostering sustainable work practices, particularly in promoting innovative behavior and work engagement.

Modern organizations require employees with diverse skills and expertise to address complex and dynamic challenges. While teams are common in contemporary workplaces (Kozlowski & Bell, 2012), our focus is on understanding how individual employees’ autonomy and their perception of performance pressure affect their work outcomes. Individual employees are expected to achieve increasingly demanding goals through high levels of work engagement (Saks, 2006), while simultaneously developing innovative approaches to task performance. This dual requirement for engagement and innovation has become critical in organizations’ long-term survival in uncertain environments (Anderson et al., 2014).

The question then becomes the following: How can organizations foster sustainable work engagement and innovative behavior at the individual level while managing performance pressures? Job autonomy has received significant attention as a key antecedent of both outcomes (Hakanen & Roodt, 2010; Bakker & Geurts, 2004). According to Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and the Job Demand–Resource Model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), job autonomy serves as a vital resource that promotes engagement and innovative behavior through enhanced intrinsic motivation. Autonomy allows individuals the freedom and independence to perform their tasks in ways that align with their capabilities and preferences (Hackman & Oldham, 1975).

However, the relationship between job autonomy and employee outcomes is complex. Previous research has presented mixed findings regarding the benefits of job autonomy (Farh & Scott, 1983; Langfred, 2000, 2004). While autonomy generally positively affects organizational effectiveness, certain contextual factors may minimize or negate its benefits. Of particular interest is how individuals’ perception of performance pressure within their team environment might affect their response to job autonomy. Langfred (2004) suggest that high performance pressures might hinder the positive effects of job autonomy by shifting the focus from intrinsic motivation to external performance demands.

This study addresses these complexities by examining how individuals’ perception of team performance pressure moderates the relationship between their job autonomy and two key outcomes: work engagement and innovative behavior. Our research objectives are threefold:

- To examine how job autonomy contributes to work engagement in organizations;

- To investigate the relationship between job autonomy and innovative behavior in organizational contexts;

- To understand how individual perception of team performance pressure moderates these relationships, affecting the dynamic interplay between autonomy and outcomes.

This research contributes to developing both theory and practice by examining how organizations can balance individual autonomy and performance pressure in contemporary work environments. By understanding these relationships, organizations can better design management practices that promote both immediate performance and long-term effectiveness through enhanced employee engagement and innovation capacity.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Job Autonomy

Organizations have long used job autonomy (Langfred, 2004) as a key component of sustainable human resource management practices. However, the widespread systematic use of autonomy within organizations has only recently been considered. Until the mid-1980s, systematic use was rare; it began to be used in the 1990s. Employee participation related to autonomy was more commonly used than job autonomy (Ledford et al., 1995).

Job autonomy refers to the extent to which members can exercise a high level of autonomy, independence, and discretion in performing their tasks (Morris & Feldman, 1996; Shirom et al., 2006). Given its long-standing conceptualization, it has long been studied as a key factor in many theories. Job characteristics theory (Oldham et al., 1976) views job autonomy as a highly desirable work characteristic and as one of the five core elements (skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback). Job demand–control theory (Karasek, 1979) also mentions the importance of autonomy. Takeuchi (1985) argues that when managers reduce work control over members and grant discretion in relation to details, employees are motivated to be proactive and develop themselves.

Recent research further emphasizes the role of job autonomy in fostering employee engagement and innovation. Kivrak et al. (2025) highlight that job autonomy enhances intrinsic motivation, empowering employees to take ownership of their tasks and engage in creative problem-solving, a key driver of innovative behavior. This aligns with prior findings that greater autonomy leads to increased work engagement by providing employees with a sense of control over their work, ultimately reinforcing their sense of purpose and commitment. As organizations continue to adapt to rapid changes, fostering collaboration within teams has become essential in maintaining a competitive advantage. Having a high degree of discretion in one’s job encourages teamwork and knowledge-sharing within the organization, strengthening both individual motivation and overall team dynamics. Moreover, high job autonomy positively affects members’ positive emotions and happiness levels (Slemp et al., 2015), highly motivates individuals, and improves job satisfaction and performance, as previous studies (Argote & McGrath, 1993; Dodd & Ganster, 1996; Dwyer et al., 1992; Loher et al., 1985; Spector, 1986) have revealed.

2.2. Job Autonomy and Work Engagement

Work engagement is a higher-order construct comprising three sub-elements: vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli, 2012). This refers to the positive and fulfilling mental state that members feel toward their assigned tasks (Zhang et al., 2017). Work engagement is the opposite of job burnout. While previous organizational behavior research has focused more on job burnout, research on the positive aspects of work, such as work engagement, has been emphasized since the emergence of positive psychology. Unlike employees who suffer from burnout due to their jobs, engaged employees complete their job demands with a pleasant mindset (Schaufeli et al., 2006). The three sub-elements are as follows.

Vigor refers to a high level of energy and mental resilience and the willingness to invest effort in one’s work, with the characteristic of persistence despite difficulties. Dedication refers to being strongly involved in work and experiencing a sense of meaning, passion, inspiration, pride, and challenge. Absorption is characterized by being completely concentrated and immersed in one’s work to the extent that time passes quickly, and it is difficult to detach oneself from work. Therefore, members engaged in their work will work hard, become highly involved in their tasks, and feel immersed (Zhang et al., 2017).

The logic behind the positive (+) effect of job autonomy on work engagement can be attributed to a high level of intrinsic motivation. According to Hackman and Oldham (Oldham et al., 1976), when members are given autonomy, they perceive the outcome of a task as responsibility for their own choices, leading to a critical psychological state in which they feel the need to perform the task better. Ultimately, the tasks that they perform result from their choice; therefore, they perceive that everything depends on them. Consequently, when employees experience job autonomy, they invest a high energy level to perform their work well, leading to higher levels of vigor. They also experience higher levels of dedication as they become strongly involved in their work and higher levels of absorption as they concentrate intensely on the task. Numerous empirical studies have confirmed the positive relationship between autonomy and work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Mauno et al., 2007).

Based on the above logic and previous research, the following hypothesis is proposed regarding the relationship between job autonomy and work engagement:

Hypothesis 1:

Employees’ perceived job autonomy is positively associated with work engagement.

2.3. Job Autonomy and Innovative Behavior

Innovative behavior combines innovation and behavior and is manifested when new ideas are successfully turned into action (Amabile et al., 1996). In other words, it relates to the productive process of implementing ideas in products or services (Van de Ven, 1986); (Kanter, 1988). Scott and Bruce (1994) define innovative behavior as taking concrete actions based on creativity. In this context, employees’ innovative behavior can be defined as finding new ideas, establishing implementation plans, mobilizing necessary resources, and putting them into practice when performing tasks.

The difference between companies that achieve outstanding performance and those that are not participating in continuous innovation (Pearson, 2002) is that idea generation and implementation by employees themselves can become the source of a company’s competitive advantage (Anderson et al., 2004). Therefore, in the 21st century, with fierce competition, employees’ work engagement and innovative behavior are critical factors in sustainable organizational development (Binkley et al., 2012). However, research on innovation is still scarce in the management field in Korea, and further research is needed on the antecedents of innovative behavior.

Job autonomy is an important antecedent for employee creativity and innovative behavior (Amabile et al., 1996; Hammond et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2014; Scott & Bruce, 1994). For example, considering innovative companies such as Google, 3M, and Apple, we can see that as employees’ autonomy over their tasks increases, they exhibit more creative thinking and innovative behavior. This is because job autonomy increases a sense of control over their functions. As implementing ideas falls within their power, they will likely actively express and validate them and develop them into creative outcomes. Many studies have shown a positive relationship between job autonomy, innovative behavior (Axtell et al., 2000; Ramamoorthy et al., 2005; De Spiegelaere et al., 2014), and job creativity (Liu et al., 2011).

In particular, Hammond et al. (2011) found that job characteristics, including job autonomy, were among the key antecedents that elicited employees’ innovative behavior among all the predictors evaluated in this research. They argue that employees can find and develop optimal work methods (De Spiegelaere et al., 2014). In other words, in task performance, a certain degree of freedom to choose is necessary to find the optimized method, and freedom in the job provides this space (De Spiegelaere et al., 2014). When individuals have control over their tasks, task performance constraints are reduced, allowing them to perform their duties more creatively (Dierdorff & Morgeson, 2013).

Research has consistently demonstrated that job autonomy enhances creativity and innovation by allowing employees to explore various approaches and develop ideas through small-scale applications (Cabrera et al., 2006). Employees with higher autonomy also tend to engage more in knowledge-sharing activities.

Recent studies further emphasize the role of perceived supervisory support (PSS) in this process. Kivrak et al. (2025) found that employees with high levels of job autonomy tend to perceive their supervisors as more supportive, which fosters an environment conducive to engagement and innovation. This aligns with self-determination theory (SDT), which posits that autonomy fulfillment enhances intrinsic motivation, enabling employees to leverage their autonomy for creative work (Deci et al., 1989). While job autonomy is widely recognized as a direct antecedent of innovative behavior, considering contextual factors such as supervisory support can provide a deeper understanding of how autonomy fosters creativity in organizational settings.

Furthermore, research has confirmed that job autonomy is a strong predictor of innovative employee behavior (Axtell & Parker, 2003; Krause, 2004; Unsworth et al., 2005; Ohly et al., 2006). Grounded in job characteristics theory (Oldham et al., 1976) and SDT’s emphasis on the motivational role of autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2000), the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2:

Employees’ perceived job autonomy is positively associated with innovative behavior.

2.4. Performance Pressure

Leaders in organizations evaluate and strengthen rewards and punishments based on employees’ performance levels, competition intensifies, and employees perceive the importance of achieving the organization’s desired goals (Baumeister & Showers, 1986). This is referred to as performance pressure.

Performance pressure differs from performance goals. Previous research on job motivation showed that goals are “broadly interpreted as the internal representation of a desired state, event, or process” (Austin & Vancouver, 1996, p. 338). However, performance pressure refers to the external forces imposed on employees.

Generally, supervisors or customers are in a position to exert pressure in performance reviews or use the results of task performance (Gardner, 2012). Specifically, performance pressure is associated with negative evaluative orientations toward poor performance, beliefs that current performance is insufficient to meet desired goals, and negative emotional responses to slow progress (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). It strengthens employees’ aversive emotional reactions when progress toward a goal is slower than expected (Carver, 2001). Therefore, while performance pressure may drive employees to achieve their desired performance goals (Zhang et al., 2017), it is also possible that under high performance pressure, employees may feel constrained by external expectations and evaluation standards, which could weaken the positive effects of job autonomy.

While performance pressure is often seen as a motivational factor, recent research suggests that its effects are not always positive, particularly in contexts where employees rely on high levels of job autonomy. Liao et al. (2025) found that performance pressure can interact with workplace conditions, influencing the extent to which employees engage with their tasks. Specifically, when employees perceive high job autonomy, they tend to experience greater work engagement. However, under high performance pressure, this positive effect of job autonomy may be weakened, as employees feel constrained by external expectations and evaluation standards.

Performance pressure can be studied on the individual and team levels (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). Gardner (2012) defines team performance pressure as a combination of factors prioritizing teams that provide excellent performance, such as shared responsibility for performance, teamwork precision and evaluation, and results related to team performance.

Theoretical perspectives on team or organizational climates indicate that team performance pressure can be categorized into psychological and team-level pressures (Anderson & West, 1998; LaFollette & Sims, 1975). Psychological performance pressure reflects an individual’s perception of the importance of delivering excellent team results, whereas team-level performance pressure represents a shared perception of collective performance expectations within the team.

Regardless of performance pressure, high team performance pressure reflects employees’ perception of the importance of teams that provide excellent results (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). Furthermore, team performance pressure may hinder employees’ autonomous work responsiveness regardless of research (Zhang et al., 2017). While this study focused on individual-level performance pressure, the conceptual definition aimed to measure the performance pressure that members perceive within their teams.

2.5. Job Autonomy and Performance Pressure

Job autonomy helps employees achieve their work goals (Nahrgang et al., 2011), respond quickly to changing job demands, and buffer the negative impacts of stress factors (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Several theories have demonstrated positive effects.

The Job Demand–Resource Model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) assumes a motivational process in which job resources such as job autonomy affect work engagement. The self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) also states that employees exhibit more innovative behavior in an environment that supports autonomy.

However, studies have shown that job autonomy may not always be a beneficial resource. Some studies have confirmed a negative (−) association between autonomy and performance. In a comparative analysis of job autonomy and performance in social welfare and military organizations, Langfred (2000) argued that job autonomy negatively affects social welfare organizations but positively affects military organizations. In a later study on MBA students, he demonstrated that the relationship between autonomy and performance is moderated by the level of trust and monitoring within the team (Langfred, 2004). A recent meta-analysis revealed that not all employees with highly autonomous jobs exhibit positive work attitudes and greater happiness. Among team-level job autonomy studies, Man and Lam (Man & Lam, 2003) found that the relationship between team autonomy and performance was insignificant. Other studies have shown that the relationship between job autonomy and performance variables can vary depending on factors such as team trust (Langfred, 2004), task interdependence (Langfred, 2005), the job demand climate (Hirst et al., 2008), and job uncertainty (Cordery et al., 2010).

Given these mixed findings, this study explores the situational factors that might moderate the relationship between job autonomy and employees’ work engagement and innovative behavior. Specifically, this study introduces the concept of performance pressure as perceived by employees within their teams as a potential moderator of the effects of job autonomy on work engagement and innovative behavior.

The motivational mechanism responsible for the positive effects of autonomy suggests that the primary benefit of increased job autonomy is enhanced intrinsic motivation (Langfred, 2004). The approach that emphasizes employees (Vroom & Jago, 1988) also assumes that the beneficial effects of job autonomy are contingent on employees’ motivation and resource perception.

From a sustainable HRM perspective, excessive performance pressure may undermine the long-term benefits of job autonomy by shifting employees’ focus from intrinsic motivation to external demands.

In other words, autonomy means that employees must perform their work independently, evaluate their choices, and make decisions about future work tasks, resulting in dual-task processing (Langfred, 2004). Bandura (Bandura & Jourden, 1991) and Hackman and Oldham (Oldham et al., 1976) also argue that employees with high job autonomy can decide the methods and timing of assigned tasks and use their judgment in the work process, which makes them responsible for the outcomes.

However, autonomy does not always function as a purely motivational resource. In high-pressure environments, employees may experience autonomy not as freedom but as an additional burden in meeting external expectations. Performance pressure is defined as employees’ subjective perception of the necessity to achieve expected goals, accompanied by a sense of urgency and tension. Recent research suggests that performance pressure can drive employees toward proactive engagement or, conversely, induce work withdrawal behaviors depending on how it is appraised (Liao et al., 2025). In the context of job autonomy, high performance pressure may shift employees’ focus from intrinsic motivation to external demands, limiting the positive effects of autonomy on work engagement and innovation.

When employees experience high performance pressure, the autonomy that they possess may no longer be perceived as a resource for self-directed decision-making but rather as an obligation to meet external demands. As a result, instead of enhancing engagement and innovative behavior, autonomy under high performance pressure can lead to cognitive overload and diminished intrinsic motivation.

If the team to which the member who must perform the dual task belongs makes them feel that the task is being forced upon them because of a high level of performance pressure, it will excessively promote cognitive activity and damage the motivational process.

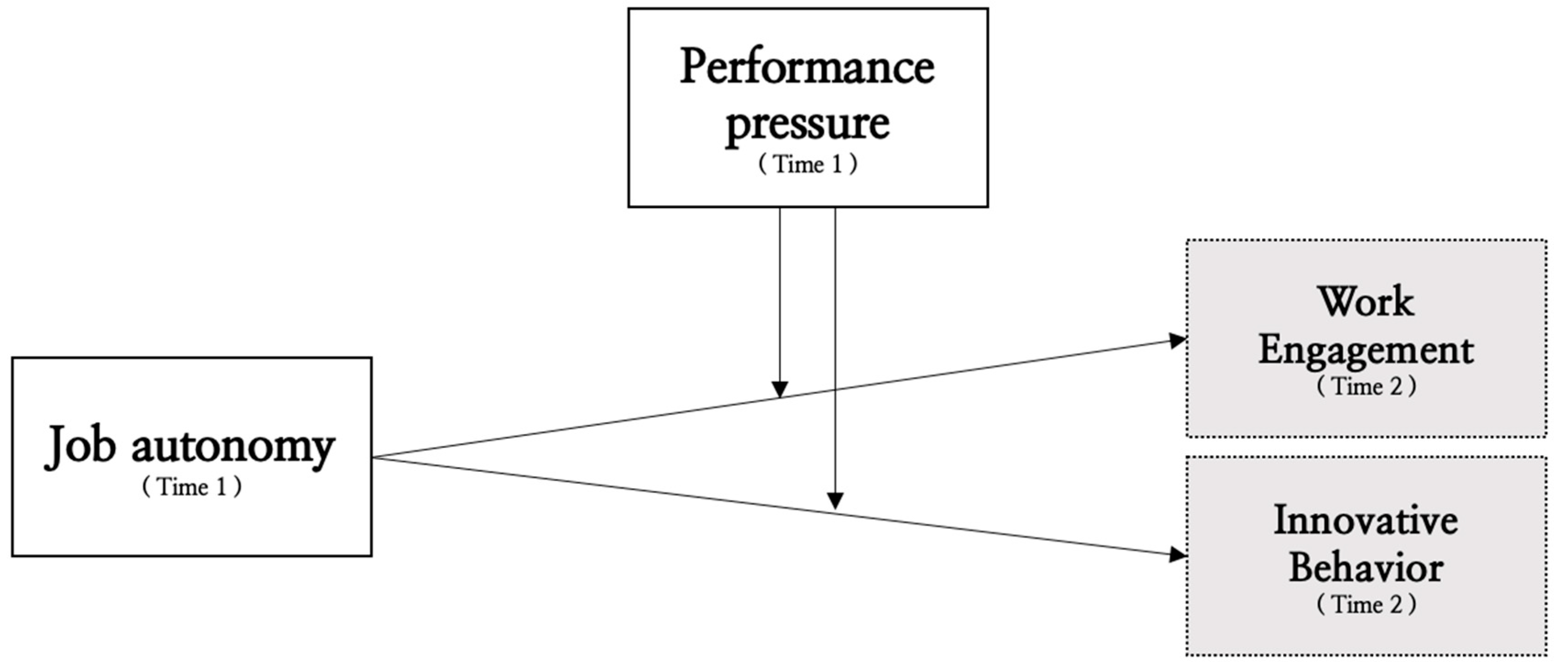

In summary, members with low levels of performance pressure within the team will have increased work engagement through job autonomy, allowing them to utilize their judgment to accomplish their work. Additionally, freedom in the work process will enable them to find and develop optimal work methods that exhibit higher levels of innovative behavior. However, for members who feel high levels of performance pressure within the team, their job autonomy makes them perceive that the tasks they have to prioritize are not based on their own decisions but rather on the team’s demands. In this situation, their work engagement decreases, and their innovative behavior is also lower (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The theoretical model of this study.

Based on this logic and previous research, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3:

The positive relationship between job autonomy and work engagement is attenuated under conditions of high performance pressure as compared to low performance pressure.

Hypothesis 4:

The positive relationship between job autonomy and innovative behavior is attenuated under conditions of high performance pressure as compared to low performance pressure.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Research Sample

For this study, we conducted a large-scale survey of employees working in various industries in South Korea. To ensure representative sampling and enhance generalizability, we employed a stratified sampling approach across different industries and organization sizes. The stratification criteria included (1) industry type (manufacturing, service, IT, and others), (2) organization size (small, <100 employees; medium, 100–499; large, 500+), and (3) employee hierarchical levels (entry-level to executive).

The data collection process involved two waves with a five-week interval to minimize common method bias, following Podsakoff et al. (2003) recommendations. In the first wave (March 2023), we measured independent variables (job autonomy) and moderating variables (performance pressure). After the five-week temporal separation, the second wave (April 2023) assessed dependent variables (work engagement and innovative behavior). This temporal separation helps reduce potential common method variance and strengthens causal inferences.

Initial surveys were distributed to 710 employees across 10 companies. After matching Time 1 and Time 2 responses and removing incomplete or invalid responses, we obtained 485 valid responses, yielding a response rate of 68.3%. The participating organizations consisted of four manufacturing companies, three service companies, two IT companies, and one company from another industry. To check for potential non-response bias, we compared early and late respondents across key study variables and found no significant differences.

The final sample included 247 males (50.9%) and 238 females (49.1%). The age distribution showed that the highest number of participants were in their 30s (44.3%), followed by those in their 40s (27.9%), those in their 20s (18.9%), and those in their 50s or above (8.9%). Regarding job positions, more than half were entry-level employees (52.4%), with the remainder consisting of middle management (22.5%), senior management (11.1%), and executives (4.5%).

To ensure data quality and in light of ethical considerations, we implemented several control measures. First, trained research assistants administered the surveys under standardized conditions. Second, all participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity through formal consent procedures. Third, each respondent was assigned a unique identifier using a coded system to match their Time 1 and Time 2 responses while maintaining anonymity. Fourth, we conducted systematic data cleaning procedures, excluding incomplete responses, checking for unusual response patterns, and verifying the consistency of matched responses. Finally, we performed preliminary analyses to identify potential outliers and verify data normality assumptions.

3.2. Measure

The survey questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The English-language instrument was translated into Korean. To ascertain the reliability and validity of the research tool, this study utilized a standard translation and back-translation process (Brislin, 1980). Additionally, the full measurement instrument is provided in the Appendix A for reference.

3.2.1. Job Autonomy

Regarding job autonomy, three items were measured at Time 1. Job autonomy was conceptualized as the extent to which employees were granted freedom, independence, and discretion in carrying out their job responsibilities. This study used 3 items from the job autonomy subscale of the Job Diagnostic Survey developed by Hackman and Oldham (Hackman & Oldham, 1975).

3.2.2. Work Engagement

Regarding work engagement, 3 items were measured at Time 2. Work engagement referred to the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral energy that members invested in their work. It was measured using the UWES-3 (Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Short Measure) by Schaufeli et al. (2019).

3.2.3. Innovative Behavior

Regarding innovative behavior, 3 items were measured at Time 2. Innovative behavior was defined as innovative work behavior that involved the development and realization of new ideas in performing one’s job tasks. It was measured using 3 items from Schuh et al. (Wu et al., 2014).

3.2.4. Performance Pressure

Regarding performance pressure, 4 items were measured at Time 1. Performance pressure was defined as the psychological burden felt by members due to their cognitive assessment of the amount of work and the required level of achievement in their team. It was measured using 4 modified and translated items from Mitchell et al. (2018).

3.2.5. Control Variables

As suggested in the proposed hypotheses, gender, age, position, and tenure were controlled for as they could potentially influence the relationships among the variables.

3.3. Analysis Methods

The empirical analysis was conducted using Stata version 16.1, following a systematic three-stage analytical approach. First, we conducted preliminary analyses to examine the psychometric properties of our measures. Second, we performed measurement model analyses to establish construct validity. Third, we tested our hypothesized relationships using hierarchical regression analyses.

In the preliminary analyses, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. Following established guidelines, we set the factor loading criterion to 0.7 or above to ensure item reliability. We also examined cross-loadings and communalities to verify the distinctiveness of our constructs.

For the measurement model, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was assessed using multiple fit indices including χ2/df, RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and SRMR, following Hu and Bentler (1999) recommendations. We also evaluated construct reliability using Cronbach’s α coefficients and composite reliability (CR) and assessed discriminant validity through average variance extracted (AVE) values.

For hypothesis testing, we employed hierarchical multiple regression analysis. Control variables were entered in the first step, followed by main effects in the second step, and interaction terms in the third step. To minimize multicollinearity concerns in testing moderation effects, all variables were mean-centered prior to creating interaction terms (Aiken et al., 1991). We also conducted simple slope analyses to interpret significant interaction effects and performed additional robustness checks including tests for outliers, influential cases, and potential violations of regression assumptions.

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis

CFA was conducted to confirm that the key variables used in the models were distinguished with adequate discrimination. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to verify the model fit. According to the general fit criteria, if the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) are above 0.90, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is below 0.08, and the ratio of the chi-squared statistic (CMIN) to degrees of freedom is below 3, then the model can be considered to have a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). The 4-factor model proposed in this study showed χ2 = 119.27, df = 59, RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.983, TLI = 0.978, and SRMR = 0.031, indicating that all fit indices were at acceptable levels. Therefore, the subsequent analyses were conducted based on this 4-factor model (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Chi-squared difference tests and fit statistics for alternative measurement models.

To prevent common method bias, the survey was conducted in two rounds with the same respondents, with an approximately 1-month time lag. Additionally, Harman’s single-factor test was performed, and the results showed that the single factor that explained the most variance accounted for 36.9% of the total variance, indicating that the common method bias issue was not severe.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables are shown in Table 2. The relationships between the variables presented in the model are mostly consistent with the hypotheses. First, the control variables of gender, age, position, and tenure were found to have high levels of correlation with the variables presented in the research model. The independent variable of job autonomy showed positive (+) correlations with work engagement and innovative behavior. Specifically, job autonomy had positive (+) correlations with work engagement (r = 0.41, p < 0.01) and innovative behavior (r = 0.54, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and consistency coefficients for each variable.

Next, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to verify the moderating effect of performance pressure on the relationships between job autonomy, work engagement, and innovative behavior. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of hierarchical multiple regression analysis of the effects of job autonomy on work engagement and innovative behavior with standardized coefficients (n = 485).

First, the interaction term between job autonomy and work engagement showed the expected negative (β = −0.10, p < 0.01) influence, as predicted. This means that performance pressure weakens the relationship between job autonomy and work engagement. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 regarding the moderating effect was supported. This suggests that when given job autonomy, employees exhibit increased vigor and dedication and high levels of absorption in their work. However, when they perceive high levels of performance pressure within their team, this positive influence is weakened.

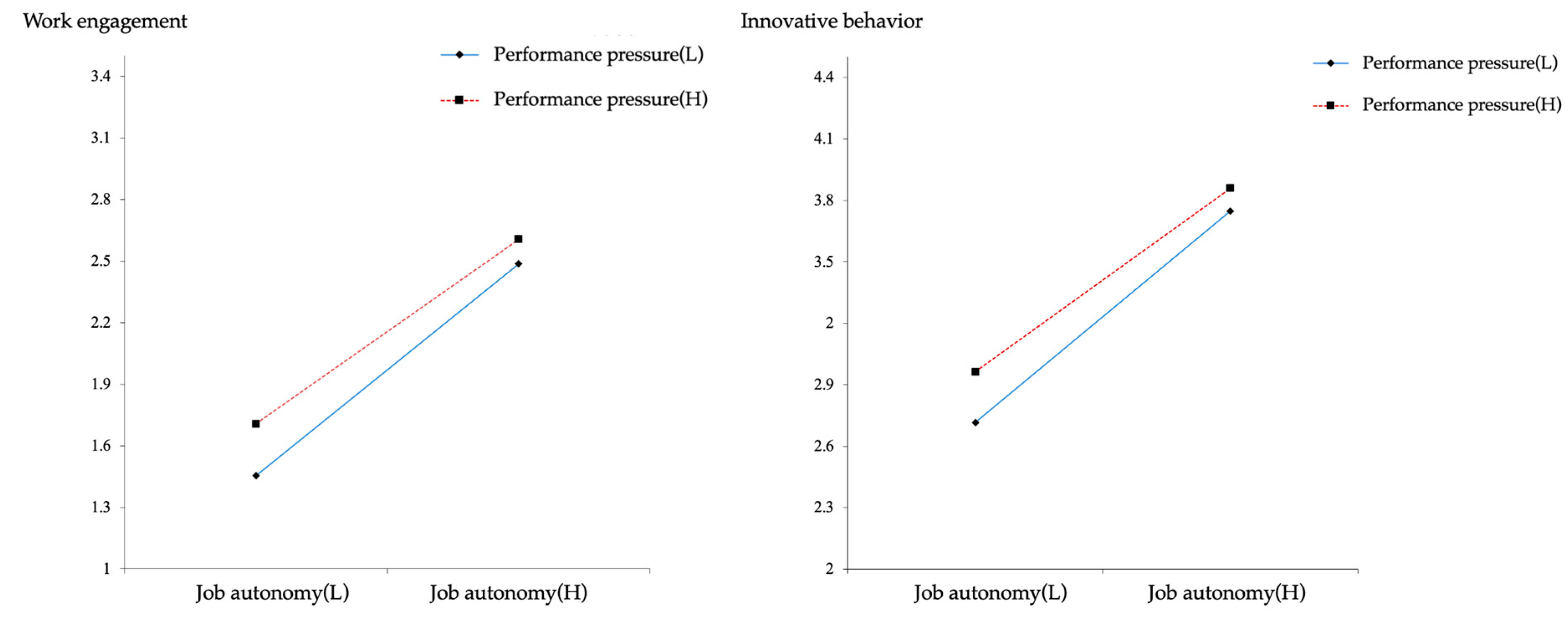

Performance pressure moderated the effects of job autonomy on both job engagement and innovative behavior in a negative direction. To examine the interaction effects more specifically, the method proposed by Aiken et al. (1991) was used to estimate regression equations, and t-tests were conducted to determine the significance of each regression coefficient. Figure 2, which visualizes the results and shows the interaction between job autonomy and performance pressure on job engagement. When the value for performance pressure was high (simple slope = 0.50, t = 8.15, p < 0.001), and when the value for performance pressure was low (simple slope = 0.34, t = 5.96, p < 0.001), the influence differed. Figure 2, shows the interaction between job autonomy and performance pressure on innovative behavior. When the value for performance pressure was high (simple slope = 0.63, t = 11.43, p < 0.001), and when the value for performance pressure was low (simple slope = 0.46, t = 9.08, p < 0.001), the influence also differed. As a result, in both cases, the higher the performance pressure, the weaker the influence of job autonomy on job engagement and innovative behavior, as evidenced by the differences in the slopes of the graphs.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of performance pressure on the relationship between job autonomy and work engagement and innovative behavior.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study examined how individual perceptions of performance pressure influence the dynamic relationship between job autonomy and key organizational outcomes: work engagement and innovative behavior. Our findings contribute to the literature in several important ways.

First, we demonstrate that job autonomy positively affects work engagement, supporting the organizational behavior perspective that employee autonomy is crucial in maintaining employee motivation and well-being. This finding extends our understanding of how organizational practices can foster employee engagement through supporting autonomy.

Second, our results confirm that job autonomy positively affects innovative behavior, highlighting its role in developing organizational capabilities. This aligns with previous research (e.g., Axtell et al., 2000) demonstrating that autonomy is a strong predictor of employee innovation, while extending these findings to contemporary organizational contexts.

Third, and most importantly, we found that individually perceived performance pressure negatively moderates the positive effects of job autonomy on both work engagement and innovative behavior. This finding addresses the inconsistent results in previous studies on job autonomy and organizational effectiveness by introducing performance pressure as a key contextual factor. Drawing on Langfred (2004) motivational and structural mechanisms, we demonstrate that high levels of perceived performance pressure can undermine the benefits of job autonomy. Specifically, when employees perceive high performance pressure, the positive influence of job autonomy on both work engagement and innovative behavior is weakened.

This moderation effect provides important theoretical insights into the conditions under which autonomy supports or constrains organizational outcomes. When excessive performance pressure leads to increased responsibility and complexity, employees may experience goal confusion and uncertainty about their responsibilities, potentially compromising their work engagement and innovative behavior. This finding is particularly significant given the limited research on factors that moderate the relationship between job autonomy and innovative behavior in organizational settings.

Our study contributes to organizational behavior theory in several ways. First, it identifies the boundary conditions under which job autonomy effectively promotes employee outcomes. Second, it demonstrates how individual perceptions of performance pressure can affect the success of autonomous work arrangements. Third, it extends our understanding of how organizations can balance autonomy and performance requirements in contemporary work environments. Beyond theoretical contributions, our findings provide key insights for organizational leaders and HR managers that can aid in managing autonomy and performance pressure effectively. To maintain employee engagement and innovation, organizations should consider the following strategy: Balanced Goal Setting for Short-Term Performance Pressure Management; while performance pressure can serve as a short-term motivator, excessive pressure counteracts the synergies of autonomy. Organizations should establish realistic goals while aligning them with long-term strategic visions to prevent burnout and disengagement.

5.2. Limitations and Future Suggestions

While our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between job autonomy and sustainable employee outcomes, several limitations should be acknowledged that suggest directions for future research.

First, our study focused on individual perceptions of performance pressure as a moderating factor in the relationship between job autonomy and employee outcomes. While this individual-level analysis provides important insights, future research could expand on our findings by examining how different levels of performance pressure (individual, team, and organizational) affect sustainable HRM outcomes. Such multi-level research could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how performance pressure operates across organizational levels and how it influences the effectiveness of autonomy-based management practices (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009; Gardner, 2012).

Second, while our research identified performance pressure as a key contextual factor, future studies should explore potential mediating mechanisms in the relationship between job autonomy and sustainable employee outcomes. For instance, feedback-seeking behavior has been suggested as a potential mediating factor that may influence how employees respond to performance pressure and maintain innovative behavior (Arun Kumar & Lavanya, 2024). Future studies could investigate whether feedback-seeking behavior or other cognitive and behavioral strategies moderate or mediate the effects of performance pressure on autonomy-related outcomes.

Third, our findings regarding the negative moderating effect of performance pressure suggest the need for more nuanced research on the conditions under which autonomy promotes sustainable outcomes. Future studies might consider three-way interactions that incorporate individual differences, such as the level of growth needed or regulatory focus, to better understand when and for whom autonomy is most effective. Additionally, researchers might explore how different types of performance pressure (e.g., development-focused versus evaluation-focused) differently affect the autonomy–outcome relationship.

Furthermore, in the South Korean organizational context, cultural values such as Confucian hierarchical structures and collectivism may intensify employees’ perception of performance pressure. Unlike Western organizations that emphasize individual autonomy, South Korean employees may experience a stronger sense of obligation to meet team expectations, potentially reducing the motivational benefits of job autonomy. Future studies should further explore how cultural factors shape the autonomy–performance-pressure dynamic.

Finally, future research could extend our findings by examining these relationships longitudinally to better understand how the effects of autonomy and performance pressure on sustainable outcomes evolve over time. This could provide insights into the long-term sustainability of different HRM practices and their effects on employee well-being and performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.J.; Methodology, Formal Analysis, Y.C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research fund grant from Honam University in 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Honam University (1041223-202205-HR-23).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results are available from the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Measurements

1. Job Autonomy (α = 0.80)

(1) I can decide how I want to work. (2) I have responsibilities in my work. (3) I have no autonomy in my work.

2. Work engagement (α = 0.88)

(1) At my work, I feel bursting with energy. (2) I am enthusiastic about my job. (3) I am immersed in my work.

3. Innovative behavior (α = 0.89)

(1) Searches out new working methods, techniques, or instruments (idea generation)

(2) Mobilizing support for innovative ideas (idea promotion)

(3) Transforming innovative ideas into useful applications (idea realization)

4. Performance pressure (α = 0.90)

(1) The pressures for performance in my workplace are high. (2) I feel tremendous pressure to produce results. (3) If I don’t produce at high levels, my job will be at risk. (4) I would characterize my workplace as a results-driven environment.

References

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N. R., De Dreu, C. K., & Nijstad, B. A. (2004). The routinization of innovation research: A constructively critical review of the state-of-the-science. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(2), 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N. R., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N. R., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 19(3), 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L., & McGrath, J. E. (1993). Group processes in organizations: Continuity and change. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(1993), 333–389. [Google Scholar]

- Arun Kumar, P., & Lavanya, V. (2024). Igniting work innovation: Performance pressure, extraversion, feedback seeking and innovative behavior. Management Decision, 62(5), 1598–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J. T., & Vancouver, J. B. (1996). Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychological Bulletin, 120(3), 338–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, C. M., & Parker, S. K. (2003). Promoting role breadth self-efficacy through involvement, work redesign and training. Human Relations, 56(1), 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, C. M., Holman, D. J., Unsworth, K. L., Wall, T. D., Waterson, P. E., & Harrington, E. (2000). Shopfloor innovation: Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Geurts, S. A. (2004). Toward a dual-process model of work-home interference. Work and Occupations, 31(3), 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Jourden, F. J. (1991). Self-regulatory mechanisms governing the impact of social comparison on complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Showers, C. J. (1986). A review of paradoxical performance effects: Choking under pressure in sports and mental tests. European Journal of Social Psychology, 16(4), 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M., & Rumble, M. (2012). Defining twenty-first century skills. In Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 17–66). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (pp. 389–444). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A., Collins, W. C., & Salgado, J. F. (2006). Determinants of individual engagement in knowledge sharing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2), 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S. (2001). Affect and the functional bases of behavior: On the dimensional structure of affective experience. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, J. L., Morrison, D., Wright, B. M., & Wall, T. D. (2010). The impact of autonomy and task uncertainty on team performance: A longitudinal field study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Connell, J. P., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Self-determination in a work organization. Journal of applied psychology, 74(4), 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Spiegelaere, S., Van Gyes, G., De Witte, H., Niesen, W., & Van Hootegem, G. (2014). On the relation of job insecurity, job autonomy, innovative work behaviour and the mediating effect of work engagement. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(3), 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierdorff, E. C., & Morgeson, F. P. (2013). Getting what the occupation gives: Exploring multilevel links between work design and occupational values. Personnel Psychology, 66(3), 687–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, N. G., & Ganster, D. C. (1996). The interactive effects of variety, autonomy, and feedback on attitudes and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17(4), 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D. J., Schwartz, R. H., & Fox, M. L. (1992). Decision-making autonomy in nursing. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 22(2), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., & Aselage, J. (2009). Incremental effects of reward on experienced performance pressure: Positive outcomes for intrinsic interest and creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30(1), 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J. L., & Scott, W., Jr. (1983). The experimental effects of “autonomy” on performance and self-reports of satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 31(2), 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. K. (2012). Performance pressure as a double-edged sword: Enhancing team motivation but undermining the use of team knowledge. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(1), 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., & Roodt, G. (2010). Using the job demands-resources model to predict engagement: Analysing a conceptual model. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, 2(1), 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, M. M., Neff, N. L., Farr, J. L., Schwall, A. R., & Zhao, X. (2011). Predictors of individual-level innovation at work: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 5(1), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, D. E., Koonce, L., & Venkataraman, S. (2008). Management earnings forecasts: A review and framework. Accounting Horizons, 22(3), 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R. M. (1988). Three tiers for innovation research. Communication Research, 15(5), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. A., Jr. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivrak, F. H., Arslan, M., & Yorno, I. A. (2025). The impact of job autonomy on employee creativity: Examining perceived supervisor support as a mediator and job difficulty as a moderator. Global Business Review, 1, 09721509251313909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, T. J. (2005). Psychological testing: A practical approach to design and evaluation. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, S. W., & Bell, B. S. (2012). Work groups and teams in organizations. In Handbook of psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 12). Kozlowski & Bell. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D. E. (2004). Influence-based leadership as a determinant of the inclination to innovate and of innovation-related behaviors: An empirical investigation. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFollette, W. R., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1975). Is satisfaction redundant with organizational climate? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13(2), 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfred, C. W. (2000). The paradox of self-management: Individual and group autonomy in work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(5), 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfred, C. W. (2004). Too much of a good thing? Negative effects of high trust and individual autonomy in self-managing teams. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfred, C. W. (2005). Autonomy and performance in teams: The multilevel moderating effect of task interdependence. Journal of Management, 31(4), 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, G. E., Jr., Lawler, E. E., III, & Mohrman, S. A. (1995). Reward innovations in fortune 1000 companies. Compensation & Benefits Review, 27(4), 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Q., Zhang, J., Li, F., Yang, S., Li, Z., Yue, L., & Dou, C. (2025). “Rat race” or “lying flat”? The influence of performance pressure on employees’ work behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1466463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Chen, X.-P., & Yao, X. (2011). From autonomy to creativity: A multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loher, B. T., Noe, R. A., Moeller, N. L., & Fitzgerald, M. P. (1985). A meta-analysis of the relation of job characteristics to job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(2), 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D. C., & Lam, S. S. (2003). The effects of job complexity and autonomy on cohesiveness in collectivistic and individualistic work groups: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 24(8), 979–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(1), 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. S., Baer, M. D., Ambrose, M. L., Folger, R., & Palmer, N. F. (2018). Cheating under pressure: A self-protection model of workplace cheating behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(1), 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J. A., & Feldman, D. C. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academy of Management Review, 21(4), 986–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., & Pluntke, F. (2006). Routinization, work characteristics and their relationships with creative and proactive behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 27(3), 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G. R., Hackman, J. R., & Pearce, J. L. (1976). Conditions under which employees respond positively to enriched work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(4), 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A. E. (2002). Tough-minded ways to get innovative. Harvard Business Review, 80(8), 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, M. P., Mackenzie, B. S., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, P. N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamoorthy, N., Flood, P. C., Slattery, T., & Sardessai, R. (2005). Determinants of innovative work behaviour: Development and test of an integrated model. Creativity and Innovation Management, 14(2), 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Work engagement: What do we know and where do we go? Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, 14(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., Hakanen, J., Salanova, M., & Witte, H. (2019). An ultra-short measure for work engagement: The UWES-3 validation across five countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A., Nirel, N., & Vinokur, A. D. (2006). Overload, autonomy, and burnout as predictors of physicians’ quality of care. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(4), 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemp, G. R., Kern, M. L., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2015). Workplace well-being: The role of job crafting and autonomy support. Psychology of Well-Being, 5(1), 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (1986). Perceived control by employees: A meta-analysis of studies concerning autonomy and participation at work. Human Relations, 39(11), 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H. (1985). Motivation and productivity. In L. Thurow (Ed.), The management challenge. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, K. L., Wall, T. D., & Carter, A. (2005). Creative requirement: A neglected construct in the study of employee creativity? Group & Organization Management, 30(5), 541–560. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven, A. H. (1986). Central problems in the management of innovation. Management Science, 32(5), 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroom, V. H., & Jago, A. G. (1988). The new leadership: Managing participation in organizations. Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. P., Rausch, J., Rohan, J. M., Hood, K. K., Pendley, J. S., Delamater, A., & Drotar, D. (2014). Autonomy support and responsibility-sharing predict blood glucose monitoring frequency among youth with diabetes. Health Psychology, 33(10), 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.-C., Mai, Q., Tsai, S.-B., & Dai, Y. (2018). An empirical study on the organizational trust, employee-organization relationship and innovative behavior from the integrated perspective of social exchange and organizational sustainability. Sustainability, 10(3), 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Jex, S. M., Peng, Y., & Wang, D. (2017). Exploring the effects of job autonomy on engagement and creativity: The moderating role of performance pressure and learning goal orientation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32(3), 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).