Abstract

This study reframes closure intention in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as an ex ante diagnostic signal rather than a post-mortem symptom of failure. The survey evidence from 385 Ecuadorian SMEs was analyzed in two stages; confirmatory factor analysis validated the scales capturing environmental pessimism and personal pressures, and a structural equation model confirmed that both latent constructs directly heighten exit propensity. A binomial logistic regression model correctly classified 71% of the cases and explained 30% of variance. Five variables proved decisive: low-level liquidity (OR = 0.84), a high debt-to-equity ratio (1.41), weak profitability (0.14), negative environmental perceptions (1.72), and a shorter operating tenure (0.91); the sector and the firm size were non-significant. The combined CFA-SEM-logit sequence yields practical early warning thresholds—debt-to-equity ratio > 1.4, current ratio < 1.0, and ROA < 0.15—that lenders, advisers, and entrepreneurs can embed in dashboards or credit screens. Recognizing closure intention as a rational, strategic step challenges the stigma surrounding exit and links financial distress and the strategic exit theory. Policymakers can use the findings to pair debt relief and liquidity programs with cognitive bias training that helps owners interpret risk signals realistically. For scholars, the results highlight closure intention as a dynamic learning process, especially pertinent in emerging economies characterized by informality and institutional fragility.

1. Introduction

Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) underpin employment, innovation, and regional output around the world (Nguyen et al., 2023; Santana, 2022). When an SME closes, the repercussions cascade across owners, workers, creditors, and local communities, curbing development and amplifying unemployment (Tao & Zhou, 2023). Anticipating closure therefore matters for both entrepreneurs and policymakers because early detection enables support measures that can avert—or at least reduce—those losses (Pretorius, 2009; Costa et al., 2023).

Most empirical work approaches exit ex post, modelling bankruptcy or liquidation once this event has occurred. We adopt a different angle and examine closure intention as a pre-emptive diagnostic signal that entrepreneurs emit when they judge continued operation to be untenable (Cucchi et al., 2022). This forward-looking lens recasts exit as a strategic option rather than a stigma-laden failure and allows us to scrutinize the information set that guides the decision.

Because publicly available micro-data on bureaucracy, corruption, and tax opacity are scarce for Ecuadorian SMEs, the present study focuses on variables that entrepreneurs can report reliably in real time. Four blocks are considered: (i) firm-level finances (liquidity, leverage, profitability, and interest coverage); (ii) operating tenure; (iii) personal or family circumstances; and (iv) a perceptual index that summarizes credit availability, administrative burden, macro-economic volatility, and competitive pressure. In this way, the institutional climate is incorporated through how it is experienced rather than through unavailable administrative scores, ensuring consistency between the research questions and the empirical design.

By positioning closure intention at the intersection of financial distress, institutional constraints, and entrepreneurial cognition, this study advances the strategic exit theory and delivers an early warning tool that policymakers in emerging economies can employ to identify at-risk firms before irreversible decline sets in.

Closure intention surfaces at pivotal moments in the firm life-cycle, and when detected early, becomes a practical diagnostic tool for entrepreneurs and policymakers alike (Costa et al., 2023; Harel et al., 2022). Analyzing its drivers sheds light on the concrete hurdles owners face—liquidity shortfalls, debt pressure, and hostile market signals—and clarifies which interventions can minimize the economic and social fallouts (Tao & Zhou, 2023). It also exposes the cognitive shortcuts that guide entrepreneurial judgement, revealing how risk is framed and options are weighed (Coad, 2013). By making those heuristics visible, entrepreneurs can fine-tune their decision rules, strengthen resilience, and plan smoother transitions when exit is unavoidable (Politis & Gabrielsson, 2009; Pretorius, 2009).

Beyond finance and strategy, closure carries a human dimension. Recognizing the possibility of exit in advance helps founders manage the stigma often attached to business failure, protects their psychological well-being, and turns personal experience into shared learning that enriches local entrepreneurial networks (Metzger, 2008; Kibler et al., 2020).

The stakes are particularly high in Ecuador, where SMEs generate roughly 24% of jobs and 15.9% of national sales (Rodríguez-Mendoza & Aviles-Sotomayor, 2020), yet operate under persistent credit constraints, low-level productivity, and uneven competitiveness (Yance Carvajal et al., 2017). Recent survey evidence shows that a lack of profitability (37%), limited financing (21%), and personal issues (19%) top the list of closure motives, followed by fiscal or bureaucratic burdens and COVID-19 after-effects (Lasio et al., 2024). Although our dataset does not include direct administrative or corruption scores, these structural pressures are captured indirectly through owners’ perceptions of credit access, bureaucratic load, macro-volatility, and competitive intensity, the very signals that shape closure intention in the Ecuadorian SME landscape.

Despite the growing body of exit research, most studies still focus on post-mortem accounts of failure, dissecting firms only after operations have stopped. Far fewer examine closure intention as a forward-looking, preventive signal (Stokes & Blackburn, 2002; Tao & Zhou, 2023). As a result, the early warning signs and the decision rules entrepreneurs apply before discontinuation remain poorly understood. Conceptual fuzziness—especially the routine conflation of “closure” with “failure”—further complicates cross-study comparisons and perpetuates the stigma attached to strategic exit (Coad, 2013; Costa et al., 2023; Headd, 2003).

The cross-country evidence shows both universal and context-specific drivers. In Germany, for instance, excessive debt and weak interest coverage ratios predict closure (Metzger, 2010), while studies in Southeast Asia highlight board heterogeneity and informality (Nguyen et al., 2023). Latin American work places more weight on family obligations and human capital gaps (Carranza et al., 2018). These differences underscore the need to factor in entrepreneurs’ perceived environmental constraints, especially in emerging markets where formal institutional data are scarce.

Against this backdrop, this study (i) clarifies the construct of business closure intention; (ii) pinpoints the financial, firm-level, personal, and perceptual factors that shape that intention in SMEs; (iii) develops a binary logistic regression model capable of predicting closure intention; and (iv) converts the resulting evidence into actionable recommendations for policymakers and SME support programs.

Departing from the traditional ex post designs (Ghosh & Yayi, 2025; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., 2023), we offer a prospective model that blends hard financial indicators with owners’ real-time perceptions of credit access, bureaucracy, macro-volatility, and competition. Framing closure intention as an intermediate diagnostic stage supplies an early-detection tool that can trigger targeted interventions before bankruptcy or liquidation ensues. In doing so, this study advances the exit theory; enriches the dynamic capabilities lens (Teece et al., 1997); and equips policymakers, development agencies, and labor market institutions with evidence they can deploy in time to preserve economic and social values (Dvouletý, 2022; Marshall et al., 2015).

2. Theoretical Framework

Business closure is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon that has received increasing attention in the entrepreneurship and small business literature. Some scholars emphasize that closure is not a uniform or monolithic event, but rather a multifaceted process influenced by a variety of motivations—economic, personal, and strategic—which cannot be attributed to a single cause (Bates, 2005; Havila & Medlin, 2012; Headd, 2003; Liedholm, 2002; Nucci, 1999). Terminology such as “liquidation” (Nguyen et al., 2023), “business death” (Coad, 2013), “dissolution” (Nucci, 1999), and “discontinuance” (Everett & Watson, 1998) reflects the diversity of perspectives in the field, ranging from negative to neutral or even positive interpretations of business exit.

Traditionally, many studies have conflated business closure with failure, assuming that all closures are inherently negative outcomes (Liedholm, 2002; Teh et al., 2023). Within this framework, closure is typically associated with financial distress, insolvency, or a poor performance (Costa et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2023). However, this interpretation overlooks that closure can also stem from voluntary, deliberate, and rational decisions that are not necessarily linked to underperformance. Personal motivations, life goal reorientations, and strategic pivots may prompt entrepreneurs to close a still-profitable venture (Politis & Gabrielsson, 2009). Closure may also occur through mechanisms such as voluntary liquidation, a merger, and business acquisition (Carranza et al., 2018; Costa et al., 2023; Dvouletý, 2022).

Recently, the literature has increasingly adopted more nuanced views. Studies by Headd (2003), Dvouletý (2022), Tao and Zhou (2023), and Bates (2005) reveal that many entrepreneurs consider their businesses successful at the time of closure. These cases challenge the assumption that exit is inherently negative, suggesting instead that closure may represent a strategic decision, a form of entrepreneurial maturation, or a stepping-stone to new ventures. Politis and Gabrielsson (2009) argue that even closures triggered by performance issues can foster deep entrepreneurial learning. Simultaneously, an intermediate position acknowledges that while failure and closure may overlap, they are not conceptually interchangeable; not all business failures lead to closure, and not all closures result from failure (Fritsch et al., 2006; Kibler et al., 2020; Ucbasaran et al., 2010). Additionally, some authors differentiate between successful and unsuccessful closures, depending on whether the exit was voluntary and strategically driven, or imposed by adverse circumstances (Bates, 2005; Costa et al., 2023; Stokes & Blackburn, 2002). The concept of closure may even extend to the shutdown of a business unit or division rather than the termination of the entire enterprise (Pretorius, 2009).

Building on this body of literature, the present study adopts a forward-looking perspective on business closure intention. Rather than treating closure solely as a reactive consequence of failure, we conceptualize it as a cognitive and strategic phase in which entrepreneurs actively consider ending operations, whether voluntarily or under external pressure. Closure intention thus represents a pre-decisional stage that may not culminate in actual discontinuation, but already involves psychological commitment and preliminary planning. This framing enables a deeper understanding of how financial conditions, contextual dynamics, and personal motivations interact to shape entrepreneurial decision making before closure becomes an irreversible outcome.

The impact of SME closure, regardless of its cause, is both broad and multifaceted. It can lead to significant job losses, negatively affecting household incomes and slowing down the recovery of local economies (Costa et al., 2023; Ingirige & Wedawatta, 2018). Given that SMEs often serve as foundational pillars of community resilience, their disruption or disappearance can produce far-reaching economic and social consequences that extend well beyond monetary losses (Ingirige & Wedawatta, 2018). Financial damage is not limited to business owners; creditors, suppliers, and other stakeholders are also affected (Costa et al., 2023; Metzger, 2010). In some sectors, a reduced number of providers can diminish competition, raise prices, and ultimately harm consumers (Costa et al., 2023; Liedholm, 2002). At a personal level, business closure may be a deeply distressing experience for entrepreneurs, frequently accompanied by emotional strain and cognitive distortions, such as the need to protect self-esteem or rationalize decisions (Coad, 2013; Metzger, 2008).

Variables Influencing Business Closure Intention

The decision to close an SME is shaped by a complex interplay of financial, managerial, contextual, and personal factors. Table 1 summarizes the key empirical findings from previous studies, illustrating the multidimensional nature of the determinants that influence closure intention.

Table 1.

Authors and studied variables.

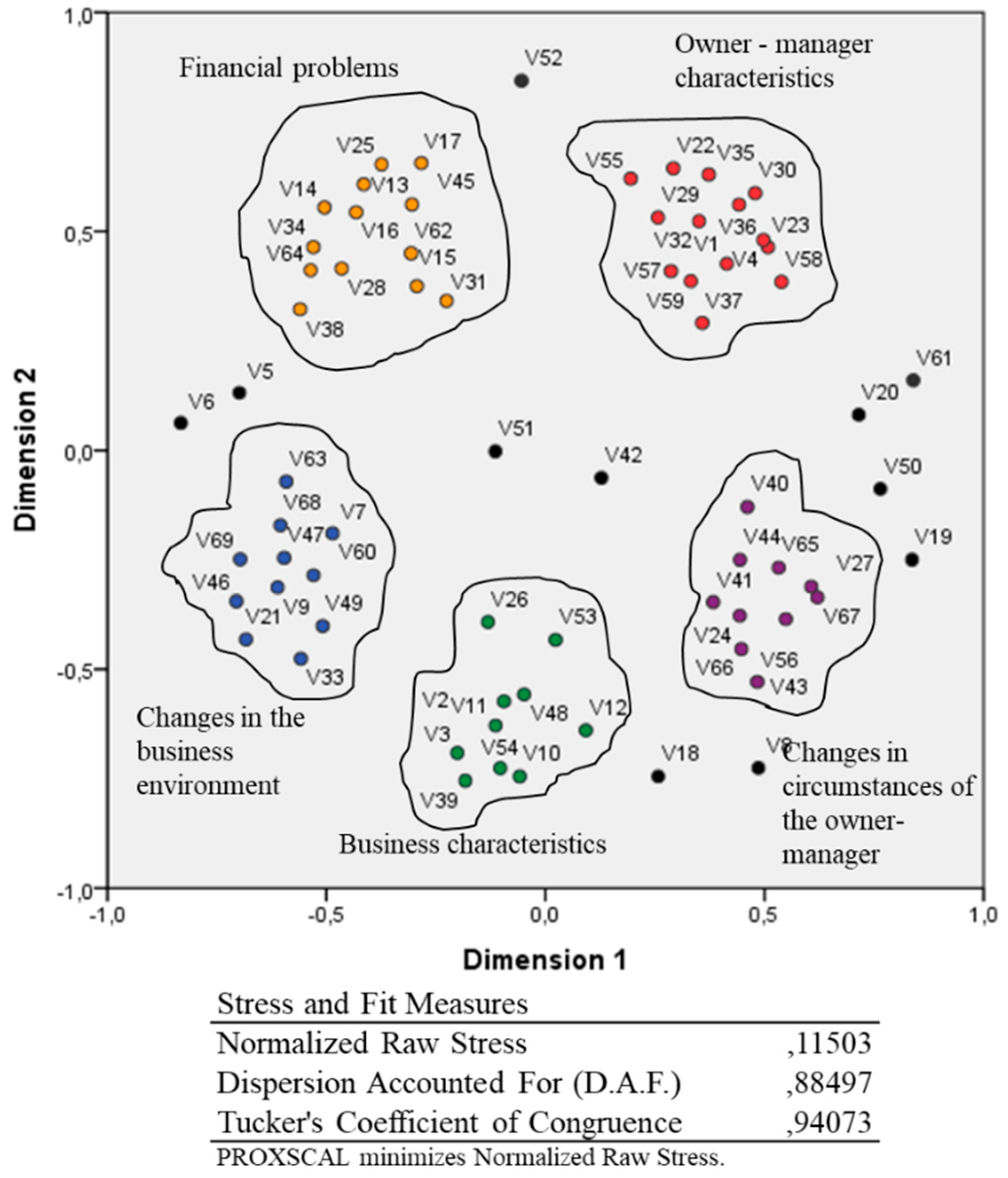

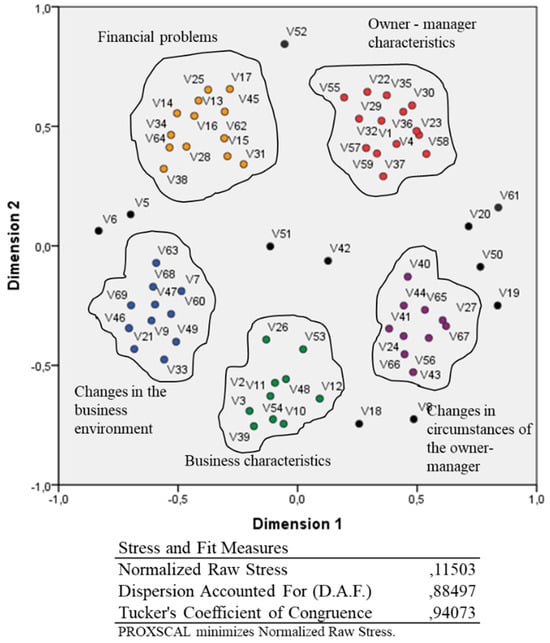

To enhance conceptual clarity and minimize redundancy, we organized the variables into five thematic clusters using Multidimensional Scaling (MDS), a statistical technique that groups conceptually related constructs into interpretable dimensions, while preserving their semantic proximity (Carroll et al., 2005). These clusters, visualized in Figure 1, serve as the foundation for the analytical framework discussed in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Results of Multidimensional Scaling.

Cluster 1: Financial Distress. Financial distress stems from a range of challenges, including liquidity shortages, excessive debt burdens, declining sales, and the failure to meet profitability targets (Carranza et al., 2018; Everett & Watson, 1998; Pretorius, 2009). These factors often interact in a mutually reinforcing cycle; limited access to capital intensifies liquidity constraints, which, in turn, increases the risk of insolvency. SMEs with a history of underperformance typically face greater difficulty in securing external financing, further compounding their financial vulnerability and raising the likelihood of closure (Costa et al., 2023).

Cluster 2: Owner–Manager Characteristics. This cluster encompasses attributes related to the owner–manager’s profile, including age, education level, professional experience, risk tolerance, adaptability, and history of prior business failures (Aghaei & Sokhanvar, 2020; Coad, 2013; Cultrera, 2016). While older entrepreneurs may possess greater experience, they may also be less inclined to embrace innovation or adapt to rapid market changes. Conversely, more educated managers are often more likely to implement data-driven strategies and structured decision-making processes (Liedholm, 2002; Ucbasaran et al., 2010; Khademi, 2023). Previous entrepreneurial setbacks or unmet business expectations can increase risk aversion, ultimately influencing future decisions regarding exit or continuity (Marshall et al., 2015).

Cluster 3: Changes in the Business Environment. This cluster reflects the influence of external pressures on closure intention, including adverse macro-economic conditions, intensifying market competition, rising labor costs, industry overcapacity, evolving consumer preferences, and shifting regulatory frameworks (Costa et al., 2023; Tao & Zhou, 2023; Yeboah-Assiamah et al., 2023). For instance, economic recessions often erode the profit margins, while digital disruption may drastically alter the demand structures and customer expectations (Stokes & Blackburn, 2002). SMEs operating in sectors characterized by high volatility—such as Manufacturing and retail—are particularly susceptible to environmental shocks and may be forced to consider exit as a survival strategy.

Cluster 4: Business Characteristics. Structural vulnerabilities—such as a small firm size, rural location, informality, sectoral limitations, and short operational history—also contribute significantly to closure risk (Dvouletý, 2022; Nucci, 1999; Pretorius, 2009; Khademi, 2023). Smaller enterprises often lack the economies of scale needed to absorb economic shocks, while informal businesses face systemic barriers to accessing formal credit markets (Aghaei & Sokhanvar, 2020; Lasio et al., 2024). Rural SMEs are frequently disadvantaged by poor infrastructure and limited market access, and firms operating in sectors with low entry barriers are subject to intense competitive pressures that can accelerate discontinuation.

Cluster 5: Changes in Owner–Manager Circumstances. Personal life events and evolving circumstances—including family obligations, psychological burnout, health problems, retirement, and alternative career opportunities—can also influence closure decisions (Bates, 2005; Carranza et al., 2018; Politis & Gabrielsson, 2009). For example, female entrepreneurs may prioritize caregiving responsibilities, while burnouts or attractive job offers can prompt voluntary exit from otherwise viable ventures (Metzger, 2008). Health-related crises may render the continued operation of the business infeasible.

MDS analysis confirms the interdependence among these five clusters, reinforcing a holistic view of closure intention as a dynamic and multidimensional process shaped by the interaction of diverse financial, contextual, and personal factors. This framework underpins our predictive model by integrating objective indicators (e.g., liquidity ratios and debt levels) with subjective and contextual dimensions (e.g., perceived environmental pressure and personal life events). By adopting this comprehensive approach, we move beyond the binary conceptions of business failure to capture the nuanced pathways that lead to closure intention.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the sampling strategy, data collection procedure, measurement instruments, validation steps, and analytical techniques used to model SME closure intention.

3.1. Research Design and Sampling

We employed a cross-sectional survey of Ecuadorian small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), an effectively infinite population for statistical purposes (National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, n.d.). Because no comprehensive registry exists, a non-probability convenience strategy was adopted. Owner–managers were recruited through regional business associations, entrepreneurship hubs, and professional networks; each received a brief study description that highlighted voluntary, anonymous participation and the right to withdraw at any time. The data were captured and analyzed with IBM SPSS 25. The final dataset contains 385 complete cases, a size sufficient for the logistic and latent variable models reported below.

To reduce social desirability bias, (i) all questionnaires were anonymous, (ii) item wording was neutral and descriptive, and (iii) the interviewers were trained to avoid evaluative cues. Although convenience sampling limits statistical generalizability, it fits this study’s exploratory, diagnostic purpose and provided direct access to the key decision-makers.

Sample profile. The owner–managers average 34.5 years of age (SD = 7.54); their firms have been operating for 8.4 years on average (SD = 6.31). Sector representation—after collapsing the original five-sector scheme into four dummies for parsimony—comprises Agriculture (11.7%), Manufacturing (5.5%), Trade (35.6%), and Construction (6.0%), with Services (41.3%) serving as the reference group. Table 2 details the sector, gender, and education distributions. To preserve model parsimony and avoid sparse cell issues, the initial five-sector scheme was collapsed into four dummy variables (Agriculture, Manufacturing, Trade, and Construction), using Services—the largest group—as the reference category.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of sample.

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

Fieldwork was carried out through structured, face-to-face interviews conducted on-site at each firm. Every session followed the same sequence:

- Focal question. The interviews opened with a single dichotomous item: “Have you had the intention to close your business in the past year?” (yes = 1, no = 0).

- Self-administered instruments. The respondents then completed two Likert-type questionnaires that captured (a) perceptions of the external environment and (b) personal or non-economic circumstances.

- Financial statements. Finally, the owner–managers provided the most recent income statement and balance sheet excerpt needed to compute the liquidity, leverage, profitability, and interest coverage ratios.

Each interview lasted 40–50 min and was conducted by a trained researcher who remained available for clarification, but refrained from giving evaluative feedback. The ethical safeguards—voluntary participation, anonymity, the right to withdraw, and post-study feedback—were communicated during recruitment (see Section 3.1) and reiterated before the questionnaire began.

Because closure intention is self-reported and susceptible to social desirability bias, three additional precautions were implemented: (i) no personally identifying information was recorded; (ii) all items used neutral, descriptive wording; and (iii) the interviewers were trained to avoid implying that any answer was preferred. This protocol proved effective in securing candid responses from the owner–managers directly involved in operational and strategic decision making. While the convenience sampling approach limits statistical generalizability, it aligns with the exploratory, diagnostic aims of this study and yielded context-rich data suitable for both logistic and latent variable analyses.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Closure Intention

Closure intention was measured with a single dichotomous item posed at the start of every interview: “Have you had the intention to close your business in the past year?” The responses were coded 1 = “Yes” or 0 = “No.”

Although the replies to follow-up probes were not entered into the statistical models, the qualitative insights they generated were critical for instrument development. Early pilot interviews helped determine vocabulary, refine the wording of Likert items, and confirm that the constructs resonated with the owner–managers’ lived experience. Integrating these qualitative checks with the final survey reduced socially desirable responding and ensured that the quantitative phase was firmly grounded in real-world decision-making dynamics.

3.3.2. Perceived Business Environment

The Assessment of Owner-Managers’ Perception of the Business Environment is a 24-item, self-administered questionnaire developed from prior exit research (Costa et al., 2023; Everett & Watson, 1998; Mao et al., 2020; Marshall et al., 2015; Stokes & Blackburn, 2002; Tao & Zhou, 2023). The items cover macro-economic conditions, credit access, bureaucracy, market competition, labor costs, shifts in consumer preference, sectoral overcapacity, demand fluctuations, and interest rate variability. Respondents rate each statement on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly disagree;” 7 = “Strongly agree”). Internal consistency is acceptable (Cronbach’s α = 0.79). Detailed exploratory and confirmatory factor results—KMO = 0.942; six factors explaining 54.4% of variance; CFI = 0.966; RMSEA = 0.030; and SRMR = 0.040—are reported in Section 3.4.

3.3.3. Personal and Non-Economic Circumstances

To capture the owner-specific motives for exit, we developed the Evaluation of Owner-Manager Personal and Non-Economic Circumstances Impacting Business Closure Intentions, a 27-item scale adapted from Bates (2005), Carranza et al. (2018), Metzger (2008, 2010), and Politis and Gabrielsson (2009). This instrument evaluates opportunity cost, burnout, health problems, family responsibilities, the appeal of salaried employment, plans to start a new venture, retirement, and alternative career options. The items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly disagree;” 7 = “Strongly agree”).

The psychometric quality is strong: Cronbach’s α = 0.928. EFA (KMO = 0.941; Bartlett p < 0.001) extracted three factors that explain 67.5% of variance; the CFA indicators (CFI = 0.892, RMSEA = 0.054, and SRMR = 0.047) indicate an acceptable overall fit, supporting the scale’s factorial validity.

3.3.4. Financial and Firm-Level Indicators

Objective firm characteristics were drawn from the most recent financial statements supplied by each owner–manager:

- Annual revenue (USD 000s)—proxy for firm size.

- Current ratio—liquidity measure (current assets ÷ current liabilities).

- Debt-to-equity ratio—leverage indicator (total liabilities ÷ shareholders’ equity).

- Interest coverage ratio—ability to service debt (EBIT ÷ interest expense).

- Return on assets (ROA)—profitability metric (net income ÷ total assets).

- Years in operation—operating tenure since founding.

- Sector dummies—Agriculture, Manufacturing, Trade, and Construction, with Services as the reference category.

These variables complement the perceptual and personal constructs by capturing the firm’s financial health and structural contexts.

3.4. Measurement Validation

Construct validity was assessed in two sequential steps—exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)—for each perception scale following best-practice guidelines (Hair et al., 2019).

3.4.1. Perceived Business Environment (24 Items)

Exploratory phase. Principal component extraction with Varimax rotation produced a KMO of 0.942 and a significant Bartlett test result (χ2 = 2775.08, df = 276, p < 0.001), confirming sampling adequacy. Six components with eigenvalues > 1 explained 54.4% of the total variance (factor-specific shares are reported in Table 3). All the factor loadings exceeded 0.50, and communalities ranged between 0.38 and 0.76, demonstrating convergent validity.

Table 3.

Psychometric summary of latent constructs.

Confirmatory phase. Six-factor CFA estimated using the full sample (N = 385) showed an excellent fit: CFI = 0.966, RMSEA = 0.030 (90% CI 0.025–0.035), and SRMR = 0.040. Although χ2 was significant (χ2 = 338.70, df = 252, p < 0.001)—a common outcome with moderately large samples—the residual-based indices meet Hu and Bentler’s (1999) cut-offs (CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, SRMR ≤ 0.08).

3.4.2. Personal and Non-Economic Circumstances (27 Items)

Exploratory phase. EFA yielded a KMO of 0.941 (Bartlett χ2 = 3645.91, df = 351, p < 0.001) and revealed three components with eigenvalues > 1, jointly accounting for 67.5% of variance. The loadings ranged from 0.23 to 0.95; cross-loadings were minimal (<0.20).

Confirmatory phase. Three-factor CFA produced CFI = 0.892, RMSEA = 0.054 (90% CI 0.046–0.061), and SRMR = 0.047, a moderate, yet acceptable fit given the scale length and model complexity. RMSEA and SRMR fall within the recommended bounds, lending support to the theoretical structure despite the slightly sub-optimal CFI.

3.4.3. Summary and Further Evidence

Both the scales therefore meet—or closely approach—the Hu and Bentler (1999) benchmarks, confirming factorial validity. Table 3 lists the standardized loading ranges, the average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s α, and the factor-level variance explained, thereby documenting the convergent and discriminant validities in detail.

3.5. Analytical Strategy

3.5.1. Binary Logistic Regression (BLRM)

We employed binary logistic regression—a generalized linear model using a logit link function—to estimate the probability of a dichotomous outcome based on one or more independent variables (Osborne, 2015; Pituch & Stevens, 2016). The model produces regression coefficients, odds ratios, and p-values. Negative coefficients indicate a decreased likelihood of the event occurring, while odds ratios greater than one signify increased likelihood. In contrast to linear regression, which may yield probability estimates outside the [0, 1] interval, logistic regression constrains predictions within this valid range (Rana et al., 2010; Field, 2018).

To evaluate the quality and robustness of BLRM, comprehensive diagnostic analysis was conducted following the methodological guidelines proposed by Hosmer et al. (2013) and Hair et al. (2019). The model’s overall significance was assessed using the Chi-square statistic, with a p-value less than 0.05 indicating that the model provides a significantly better fit than a null model. Nagelkerke-adjusted R2 was used to evaluate the model’s explanatory power, with values between 0.2 and 0.4 generally considered acceptable for behavioral and social science research, though higher values are preferable (Hair et al., 2019). The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was applied to assess how well the model fits the observed data; a p-value greater than 0.05 suggests a good fit, indicating that the predicted probabilities are not significantly different from the observed outcomes (Hosmer et al., 2013). Additionally, a classification matrix was used to calculate the percentage of correctly classified cases, providing a practical measure of the model’s predictive accuracy. To detect potential multicollinearity, variance inflation factors (VIFs) and tolerance values were computed for all the independent variables, as high-level multicollinearity can inflate standard errors and complicate the interpretation of individual predictors. VIF values below 5.0 and tolerance values above 0.2 were considered indicative of an acceptable level of multicollinearity (O’Brien, 2007; James et al., 2021; Kutner et al., 2005). These diagnostic procedures ensured the rigorous validation of the model, enhancing both the reliability and the interpretability of the findings. Further sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the stability and robustness of the estimated parameters.

3.5.2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

Given the nature of the latent constructs involved—Assessment of the Owner–Manager’s Perception of the Business Environment and Owner–Manager Personal and Non-Economic Circumstances Impacting Business Closure Intentions—a second round of analysis was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). SEM is particularly well-suited for this study as it facilitates the modeling of complex latent variables by accounting for measurement error and shared variance among multiple observed indicators, thereby offering a more accurate representation of the underlying theoretical constructs. Moreover, SEM allows for the simultaneous estimation of multiple relationships within the hypothesized model, capturing nuanced structural influences that analyses based solely on observed variables might overlook.

Model fit was evaluated using well-established indices, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Values of CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and SRMR ≤ 0.08 were considered indicative of a good model fit in line with the conventional criteria (Byrne, 2016; Hair et al., 2019).

Thus, the application of SEM provided a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of how subjective assessments of the business environment and personal circumstances jointly influence closure intentions, insights that would be less discernible through models relying solely on observed variables.

4. Results

We predicted the intention to close a business among SME owner–managers based on several independent variables: the owner–managers’ age, years in the current business, income, the debt-to-equity ratio, current liquidity, interest coverage, the return on assets (ROA), environmental perception, the economic sector, and potential personal circumstances.

As a critical step in model preparation and validation, comprehensive multicollinearity analysis was performed prior to logistic regression. Multicollinearity was negligible (see Table 4); consequently, all the coefficients can be interpreted without adjustment.

Table 4.

Multicollinearity diagnostics.

The variance inflation factors (VIFs < 3) and the tolerance values (>0.34) confirmed the independence of predictors, remaining well within commonly accepted thresholds for socioeconomic modeling. This methodological soundness supported the development of a robust analytical framework, as reflected in the model’s overall significance (F = 21.215, p < 0.001) and an adjusted R2 of 0.321. Unlike models where VIFs above five may compromise coefficient stability, our specification showed no such risks, even among the non-significant predictors (p > 0.05), whose inclusion reflects analytical transparency rather than structural bias. These findings validate the reliability of the model and offer a replicable standard for future empirical research in similar contexts.

The output referred to as Block 1 is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Omnibus tests of model coefficients.

This section of the output is central to interpreting the results, as it reflects the performance of the regression model incorporating the full set of predictors. The Omnibus tests of model coefficients provide the results of likelihood ratio chi-square tests, which evaluate whether a model with predictors offers a significantly better fit than the null model (intercept only). Effectively, this serves as an omnibus test of the null hypothesis that all the regression coefficients in the model are equal to zero (Pituch & Stevens, 2016). The results indicate that the full model fits the data significantly better than the null model: χ2(13) = 105,551, p < 0.0001.

Additionally, Table 6 presents the results of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, which further assesses the global fit of the model by comparing the observed and expected frequencies across deciles of predicted probabilities. This test provides a complementary measure of model adequacy in capturing the observed data structure.

Table 6.

Hosmer and Lemeshow test.

The Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic serves as a goodness-of-fit test that compares observed and predicted values across subgroups of data. A significance value below 0.05 typically indicates a poor model fit (Field, 2018; Pituch & Stevens, 2016). In contrast, our non-significant result (p = 0.568) suggests that the model adequately fits the observed data, reinforcing its validity. The model summary presented in Table 7 includes the −2 Log Likelihood value along with two pseudo-R-square indices: Cox and Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2. These metrics offer an approximation of the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model, providing an additional measure of explanatory power in the absence of true R2 in logistic regression.

Table 7.

Model summary.

Nagelkerke’s R2 is commonly used because it adjusts Cox and Snell R2 to allow the statistic to range from 0 to 1, making it more interpretable (Field, 2018). In this study, the Nagelkerke R2 value indicates that approximately 32.1% of the variance in the criterion variable—closure intention—can be explained by the set of predictor variables included in the model.

The classification table (see Table 8) presents the frequencies and percentages reflecting the extent to which the model correctly or incorrectly predicts the categorical membership of the dependent variable. This table provides a practical measure of the model’s classification accuracy, helping to assess its predictive performance in applied settings.

Table 8.

Classification table a.

The model correctly predicted 74.2% of the cases in which the owner–managers reported no intention to close their business. Among the 172 cases where the owner–managers did express the intention to close, the model accurately classified 65.1%. The overall classification accuracy across all the cases was 70.1%, indicating a reasonably good predictive performance.

Table 9 presents the relationship between each predictor and the dependent variable. Coefficient B (Beta) reflects the predicted change in the log odds of the outcome for a one-unit increase in the corresponding predictor. The exponential of B, Exp(B), represents the odds ratio and indicates a multiplicative change in the likelihood of closure intention associated with a one-unit increase in the predictor variable.

Table 9.

Variables in equation.

Although none of the individual sector dummies reached conventional significance levels, a joint Wald test showed that the block of sector variables did not significantly improve the overall model fit (Wald χ2 (4) = 7.31, p = 0.121).

Interest coverage is a financial ratio that assesses a company’s capacity to meet its interest obligations using its operating earnings. It serves as a critical indicator of financial health, especially for debt-laden SMEs, reflecting their ability to avoid defaulting. In the current model, interest coverage emerged as a statistically significant and positive predictor of reduced closure intention (b = 0.111, s.e. = 0.028, p = 0.000). The odds ratio (Exp(B) = 1.118) indicates that for every one-unit increase in this variable, the odds of closure intention decrease, suggesting enhanced financial stability.

In practical terms, a higher interest coverage ratio implies that the enterprise is better positioned to generate sufficient earnings to cover its interest payments, thereby signaling less financial vulnerability. A stronger capacity to service debt obligations typically reflects healthier financial management, which can reduce the perceived need for strategic exit options. From a managerial standpoint, improved interest coverage strengthens confidence in long-term viability and reduces the likelihood of closure as a pre-emptive risk management strategy. For policy design, this finding supports interventions that enhance SMEs’ earnings capacity and debt-servicing ability as mechanisms to prevent business closure.

The debt-to-equity ratio measures a company’s leverage by comparing its total liabilities to its shareholders’ equity, serving as a direct indicator of financial structure and risk exposure. In our model, this variable is a statistically significant and positive predictor of closure intention (b = 0.337, s.e. = 0.096, p = 0.000), with an odds ratio of 1.401. This implies that for every one-unit increase in the debt-to-equity ratio, the odds of expressing closure intention rise by approximately 40.1%. High leverage can intensify financial fragility, particularly under volatile market conditions, or in response to unexpected income shocks. When debt levels exceed a firm’s capacity to generate matching revenues, the ability to absorb external stressors diminishes, restricting flexibility in strategic decision making. For many entrepreneurs, persistent debt pressure may frame business closure not as a failure, but as a rational decision to limit further losses and safeguard personal and stakeholder interests. Maintaining a balanced capital structure is therefore critical to ensuring long-term business viability and reducing the likelihood of closure as a perceived necessity.

Current liquidity refers to a business’s capacity to meet its short-term liabilities using its most liquid assets. In this study, current liquidity emerges as a statistically significant and negative predictor of business closure intention (b = −0.186, s.e. = 0.068, p = 0.006). The odds ratio of 0.830 indicates that for each one-unit increase in liquidity, the odds of expressing an intention to close the business decrease by a factor of 0.830. This inverse relationship is critical to interpret; while an odds ratio greater than one suggests a positive association with closure intention, a value below one—when statistically significant—implies a protective effect. In this case, improved liquidity reduces the likelihood of closure intentions. Sufficient liquidity enables firms to address unexpected short-term obligations, whether temporary financial instability, and pursue strategic opportunities without compromising operations. Furthermore, it bolsters stakeholder confidence, including that of owners, investors, and financial institutions. As such, current liquidity functions not only as an operational safeguard, but also as a cornerstone of sustainable financial management and long-term business viability.

Similar analysis was applied to return on assets (ROA), a key indicator of a firm’s ability to convert its total assets into net earnings. ROA serves as a proxy for operational efficiency and profitability. In the model, ROA was found to be a statistically significant and negative predictor of business closure intention (b = −2.186, s.e. = 0.586, p = 0.000). The associated odds ratio of 0.112 indicates that with every one-unit increase in ROA, the odds of expressing closure intention decrease by approximately 88.8%. This finding underscores the centrality of profitability in sustaining business operations. A higher ROA reflects better asset utilization, a stronger financial performance, and greater capacity to generate surplus value, factors that enhance internal confidence and improve external perceptions of stability. Conversely, a declining ROA signals inefficiencies that may compromise strategic decision making and lead entrepreneurs to consider closure as a rational exit route. Maintaining a healthy ROA is therefore critical to SME resilience, especially in resource-constrained or volatile environments.

A low or declining ROA can adversely affect a business through multiple interpretation channels. It may indicate deteriorating profitability and poor asset utilization, which, in turn, can trigger financial distress, reduce access to external financing, erode investor and creditor confidence, and weaken the firm’s competitive position. Together, these effects increase the perceived risk of business failure and may prompt closure as a strategic, pre-emptive decision to limit further losses. In contrast, a high and improving ROA signals sound financial management and operational effectiveness. It enhances financial stability, supports stakeholder trust, facilitates obtaining access to financing, and strengthens market positioning. These advantages promote sustained growth and adaptability, enabling the business to manage adversity, while safeguarding the interests of its owners and broader stakeholder groups. As such, ROA functions as both a financial performance metric and a strategic signal influencing closure-related decision.

The perception of the external environment plays a crucial role in shaping closure intentions. The findings of this study reveal that environmental perception is a statistically significant and positive predictor of business closure intention (b = 0.576, s.e. = 0.100, p = 0.000). The odds ratio of 1.778 indicates that for every one-unit increase in negative environmental perception, the odds of expressing closure intention increase by approximately 77.8%. This result underscores the psychological and strategic implications of how the SME owner–managers interpret external conditions. When decision-makers perceive the environment as unstable, hostile, or unfavorable—due to factors such as economic uncertainty, regulatory pressure, and market saturation—they may experience heightened anxiety about the long-term viability of their businesses. Such perceptions can disrupt planning, deter investment, and ultimately catalyze closure considerations, even in the absence of immediate financial distress. In this sense, negative environmental perceptions may act as a self-reinforcing driver of closure intention, highlighting the need to cultivate adaptive capabilities and forward-looking management practices in uncertain or challenging business contexts.

The variable years of actual activity present meaningful interpretive nuances and are addressed at the end of this analysis not due to them being less importance, but rather because of their conceptual richness. This variable emerged as a statistically significant and negative predictor of business closure intention (b = −0.098, s.e. = 0.029, p = 0.001). The odds ratio of 0.907 indicates that for each additional year a firm has been in operation, the likelihood of expressing an intention to close decreases by approximately 9.3%. In other words, businesses with longer operational histories tend to not exhibit closure intention, suggesting the presence of accumulated experience, operational stability, and entrenched resource networks.

Interestingly, however, entrepreneurs with fewer years in business do not necessarily exhibit stronger closure intentions. On the contrary, early-stage entrepreneurs may demonstrate weak intention to close their firms due to heightened initial optimism, emotional and financial investment, adaptability, and a longer planning horizon focused on future growth. This resilience may also stem from the “honeymoon period” of entrepreneurship, during which owners remain committed to overcoming challenges and are reluctant to abandon their ventures prematurely.

Nonetheless, it is essential to contextualize these findings within broader business realities. The intention to close a firm is influenced not only by business tenure, but also by dynamic market conditions, sector-specific risks, and personal or contextual hardships. Therefore, while the number of years in operation is a relevant indicator, it should be interpreted as part of a more complex matrix of variables influencing strategic exit decisions. Its significance lies in capturing experience-based learning and commitment, which can act as buffers against closure under pressure.

Non-significant Variables. Several variables in the model, including age, sector classification, income level, and personal and non-economic circumstances, did not emerge as statistically significant predictors of business closure intention. Specifically, the age of the business owner showed no meaningful association with closure intentions, suggesting that entrepreneurial decisions to exit are not strongly influenced by the owner’s age in this sample. Similarly, sector classification did not significantly affect closure likelihood, indicating that the risk of closure may be more dependent on firm-specific financial and contextual factors than on the industry sector itself. Income level and personal and non-economic circumstances also failed to predict closure intentions, highlighting the complex interplay of factors beyond straightforward financial metrics. While these variables were not significant individually, their inclusion contributes to a comprehensive understanding of closure dynamics and underscores the importance of focusing on the most impactful predictors. Future research could explore potential moderating or interaction effects to uncover subtler influences these factors might have in different contexts or subpopulations.

The binomial logistic regression model reveals clear directional associations between the key predictors and SME closure intention. Among the most salient findings, the debt-to-equity ratio shows a significant positive effect; each one-unit increase raises the odds of closure intention by 40.1% (OR = 1.401), indicating that high financial leverage intensifies vulnerability and perceived business risk. In contrast, current liquidity exhibits a buffering effect; each additional unit reduces the likelihood of closure by 17.0% (OR = 0.830), emphasizing its critical role in alleviating short-term financial pressures and preserving operational continuity.

Return on assets (ROA) emerges as a decisive variable, with a one-unit increase decreasing the probability of closure intention by 88.8% (OR = 0.112). This finding reinforces the notion that profitability not only reflects financial health, but also strengthens commitment to continuity, reducing the motivation for strategic exit. Additionally, environmental perception stands out as a significant contextual determinant; for every unit increase in negative perception, closure intention odds increase by 77.8% (OR = 1.778), reflecting the demotivating influence of unstable market conditions and perceived external threats.

Finally, business tenure acts as a stabilizing factor. Each additional year in operation reduces the likelihood of closure by 9.3% (OR = 0.907), suggesting that accumulated experience, institutional learning, and strategic resilience contribute meaningfully to sustaining entrepreneurial engagement and resisting premature exit. Collectively, these findings (see Table 10) highlight the multifactorial structure of closure intention, shaped by a confluence of financial capacity, external pressures, and temporal maturity.

Table 10.

Summary of key predictors of SME closure intention.

These findings not only quantify the magnitude and directionality of the predictors, but also offer practical implications for policymakers and SME practitioners. Strengthening financial health—through prudent debt management, improved access to financing, and the establishment of liquidity buffers—emerges as a critical lever to reduce closure intentions. Moreover, promoting strategic adaptability to environmental turbulence, including support for scenario planning, innovation, and responsiveness to market signals, enhances resilience. Institutional interventions aimed at supporting younger SMEs—such as targeted mentorship, reduced regulatory burdens, and access to training—may further mitigate vulnerability during the early operational stages. Together, these strategies can help curb premature closures and foster long-term SME sustainability in increasingly volatile and uncertain economic environments.

Recognizing the complex, latent, and interrelated nature of these personal factors and environmental perceptions, SEM was used to model these constructs as latent variables, accounting for measurement error and capturing their underlying structure (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Summary of key results.

The SEM results demonstrated that both negative environmental perception (β = 0.31, p < 0.01) and personal/non-economic factors (β = 0.28, p < 0.01) significantly and positively influence closure intention, revealing important structural relationships masked in logistic regression. The good fit indices of the SEM model (CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.050, and SRMR = 0.045) support the validity of this latent variable approach.

This dual methodological strategy highlights the distinct nature of the variables; environmental perception reflects an external, cognitive evaluation of business context risks, while personal factors represent internal psychological and emotional states. Together, these dimensions jointly contribute to the strategic decision-making process regarding business closure intentions in SMEs, emphasizing the importance of integrating both external and internal perspectives in closure research.

5. Discussion

This study positions closure intention as a forward-looking diagnostic signal rather than a retrospective symptom of business failure. By integrating the financial ratios, the owner–managers’ environmental assessments, and their personal circumstances in a single model, we show that the decision to contemplate exit emerges from the joint influence of objective strain and subjective threat appraisal.

5.1. Financial and Perceptual Dynamics

Leverage, liquidity, and profitability remain central to SME survival. A one-unit rise in the debt-to-equity ratio increases the predicted probability of contemplating closure by roughly 41 percentage points, confirming the vulnerability that accompanies over-borrowing. Conversely, stronger liquidity cushions reduce that probability by about 16 points, and higher return on assets (ROA) lowers it dramatically—by more than 80 points—underscoring profitability’s protective role.

Financial pressure alone is not decisive however. When entrepreneurs judge the external environment to be highly adverse—captured here by our six-factor perception scale—the likelihood of closure intention climbs by 17 percentage points (OR = 1.724). SEM analysis corroborates this finding, showing that latent environmental pessimism exerts a direct, positive effect (β = 0.31) even after controlling for all the financial indicators. Thus, financially similar firms can diverge sharply in exit propensity, depending on how their leaders construe the environmental signals.

5.2. Personal Considerations and Temporal Effects

Personal and non-economic pressures also matter. The latent construct that groups burnout, health issues, family responsibilities, and opportunity cost exhibits a significant positive path to closure intention (β = 0.28). The effect is large enough to rival that of leverage, indicating that internal well-being can tip the balance, especially when the financial margins are thin.

Time in operation tempers these risks. Each additional year of business experience cuts the likelihood of closure intention by about nine percent, suggesting that learning, network consolidation, and legitimacy gradually offset early-stage fragility, echoing the liability-of-newness theory.

5.3. Implications for Theory and Policy

The findings build upon exit research in three ways. First, they confirm that subjective threat perception amplifies or dampens the influence of hard financial variables, bridging the cognitive behavioral and financial distress perspectives. Second, they locate closure intention on a continuum of stages—between routine strain and actual dissolution—inviting longitudinal work on how intentions crystallize into action. Third, the results demonstrate the value of modeling personal stressors as latent constructs; treating them as isolated items, as many prior studies do, masks their aggregate impact.

For policymakers, the model offers early warning thresholds; a debt-to-equity above about 1.4, liquidity below 1.0, and ROA under 0.14 should trigger proactive counseling or credit relief programs. Because perceptions independently raise the exit risk, these financial tools must be coupled with initiatives that address cognitive bias and entrepreneurial anxiety—online modules on stress management, peer-mentoring circles, and facilitated scenario planning—especially for firms in their first five years of operation.

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Several caveats merit attention. The convenience sample, though rich in contextual detail, limits statistical generalizability. Stratified probabilistic sampling would strengthen external validity. The cross-sectional design also precludes causal sequencing; panel data could reveal how initial intentions evolve into actual exits. Moreover, while our perception scale captures environmental pessimism, we lacked direct measures of entrepreneurial anxiety, resilience, and stigma, a gap future work should fill with validated psychometric instruments. Finally, the Ecuadorian setting—characterized by informality and post-COVID credit constraints—may magnify the leverage risk and the bureaucratic burden relative to more formal economies. Replications across Latin America and other emerging regions will clarify the boundary conditions.

By recasting closure intention as a proactive, multidimensional decision node, this study invites scholars to move beyond the binary failure-versus-success narratives and encourages practitioners to integrate financial governance with cognitive and emotional support when designing SME assistance programs.

6. Conclusions

This study reframes closure intention as an early diagnostic phase shaped by the interplay of financial strain, environmental pessimism, and personal pressures. High leverage and weak liquidity markedly heighten the likelihood of contemplating exit, whereas stronger profitability and longer operating tenure buffer that risk. By combining a binary logistic regression model with latent variable SEM, we translate these insights into actionable early warning thresholds, demonstrating that closure intention is a strategic precursor to discontinuation rather than a post-mortem symptom of failure.

From a practical standpoint, the findings inform the design of entrepreneurship programs that not only teach financial ratio literacy, but also strengthen entrepreneurs’ capacity to interpret psychological warning signs. SME support organizations can use these results to integrate financial and perceptual indicators into decision-making dashboards or early-alert mechanisms that trigger personalized assistance. Public agencies and trade associations can also develop programs that combine credit relief counseling with mental health resources to help entrepreneurs navigate both the economic and cognitive stressors simultaneously.

In the context of emerging economies, these interventions contribute directly to the foundations of sustainable economic growth. Reducing the likelihood of premature closures helps preserve employment, sustain productivity, and retain entrepreneurial capital within the economy. Moreover, when closure is treated not as a failure, but as a rational and informed decision, it fosters a culture of resilience and adaptive learning that encourages re-entrepreneurship and continuous innovation. The prevention of unnecessary business exits supports capital formation, reduces losses of firm-specific knowledge, and stabilizes the small business sector, which in many emerging countries represents a substantial share of national output and employment. In turn, this stabilization contributes to greater economic dynamism, improved competitiveness, and stronger institutional ecosystems capable of supporting long-term development.

The model proposed here also empowers policymakers and SME support institutions by providing evidence-based thresholds, such as a debt-to-equity ratio greater than 1.4, current liquidity below 1.0, and ROA under 0.15, that can be used to identify the firms at risk and intervene proactively. These thresholds, grounded in statistically validated indicators, offer a replicable and low-cost mechanism for guiding financial decision making in environments characterized by data scarcity and institutional fragility. By recognizing the role of cognitive distortions and subjective risk perception in shaping closure intention, this study also highlights the importance of complementing financial support with training in stress management and risk framing, particularly in volatile and highly informal economies like Ecuador.

The model further integrates financial, contextual, and cognitive variables into a coherent explanatory structure, enabling the early detection of vulnerability and timely policy responses. Its methodological design, based on observable financial data and validated perceptual scales, makes it adaptable to other national contexts and applicable to a wide range of SME types. As such, it lays the groundwork for comparative studies that examine how closure intention operates across different regulatory and institutional environments.

The limitations include the use of a non-probabilistic sample and a cross-sectional design, which constrain generalizability and causal inference. Nonetheless, the conceptual clarity and empirical robustness of the model provide a solid foundation for future research. Longitudinal studies could track how closure intentions evolve over time and how early warning thresholds relate to actual business outcomes. Multi-country replications would allow for cross-contextual comparison, and mixed-method designs could enrich interpretation by integrating registry data, financial performance records, and qualitative interviews.

Ultimately, this study contributes to strengthening the link between entrepreneurship and economic growth in emerging economies by identifying concrete barriers to SME sustainability; offering scalable and evidence-based solutions; and proposing a holistic approach that incorporates the financial, perceptual, and temporal dimensions of decision making. Recognizing closure intention as a rational, anticipatory act rather than a retrospective failure can help policymakers build more resilient, dynamic, and inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystems that promote long-term development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.-V.; methodology, G.G.-V., L.G.-V. and R.P.-C.; software, R.P.-C.; validation, A.S.-R. and L.G.-V.; formal analysis, A.S.-R. and G.G.-V.; investigation, G.G.-V., A.S.-R., R.P.-C., L.G.-V. and R.M.-V.; resources, R.M.-V.; data curation, R.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.-V.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-R.; visualization, L.G.-V. and R.P.-C.; supervision, R.M.-V.; project administration, R.M.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve any clinical procedures, biomedical experimentation, or the collection of sensitive personal data. Instead, the data were collected through anonymous surveys and interviews voluntarily completed by adult SME owner–managers, addressing only their business perceptions and general demographic characteristics. In Ecuador, according to Acuerdo Ministerial 4883 del Ministerio de Salud Pública (Registro Oficial Suplemento 173, del 12 de diciembre de 2013), ethical review by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Comité de Ética de Investigación en Seres Humanos (CEISH) is required only for biomedical or clinical research that may pose physical or psychological risks to the participants. Our study, being observational, non-interventional, and of minimal risk, is exempt under this regulation. Nevertheless, we affirm that all the procedures complied with the ethical standards of the 2013 revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, including respect for informed consent, privacy, and voluntary participation. The participants were informed of the purpose of this study and their right to withdraw at any point without consequence. No personal or identifiable information was recorded. The above is assumed to be an exemption from the ethical compliance requirement.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in this study. Prior to participation, the respondents were informed about the purpose of this research, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the confidentiality of their responses. This study involved no sensitive personal data and was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers of the journal for their extremely helpful suggestions to improve the quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aghaei, I., & Sokhanvar, A. (2020). Factors influencing SME owners’ continuance intention in Bangladesh: A logistic regression model. Eurasian Business Review, 10(3), 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, T. (2005). Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: Delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(3), 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza, Y. G., Cercado, M. J., & Solano, S. E. (2018). Feminine entrepreneurship in Ecuador. Revista Publicando, 5(14), 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J. D., Arabie, P., & Hubert, L. J. (2005). Multidimensional scaling (MDS). In K. Kempf-Leonard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social measurement (pp. 779–784). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Coad, A. (2013). Death is not a success: Reflections on business exit. International Small Business Journal, 32(7), 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. L., Ferreira, J. J., & Torres de Oliveira, R. (2023). From entrepreneurial failure to re-entry. Journal of Business Research, 158, 113699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchi, A., Gherardi, S. A., & Picon, A. (2022). Entrepreneurial exit as a strategic option: Reframing business closure as a forward-looking decision. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 17, e00313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultrera, L. (2016). Manager characteristics as predictors of failure in belgian SMEs. Reflets et Perspectives de la Vie Economique, 55(2), 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvouletý, O. (2022). Starting business out of unemployment: How do supported self-employed individuals perform? Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 12(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J., & Watson, J. (1998). Small business failure and external risk factors. Small Business Economics, 11(4), 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, M., Brixy, U., & Falck, O. (2006). The effect of industry, region, and time on new business survival—A multi-dimensional analysis. Review of Industrial Organization, 28(3), 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A., & Yayi, C. L. (2025). Business closures in uncertain times: Theory and evidence. Finance Research Letters, 81, 107514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Harel, S., Solodoha, E., & Rosenzweig, S. (2022). Can entrepreneurs who experienced business closure bring their new start-up to a successful M&A? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(9), 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havila, V., & Medlin, C. J. (2012). Ending-competence in business closure. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(3), 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headd, B. (2003). Redefining business success: Distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D. W., Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. X. (2013). Applied logistic regression (3rd ed.). Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingirige, B., & Wedawatta, G. (2018). SMEs defending their businesses from flood risk: Contributing to the theoretical discourse on resilience. In K. Engemann (Ed.), The Routledge companion to risk, crisis and security in business (pp. 224–236). Routledge Companions. [Google Scholar]

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2021). An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, A. (2023). Investigating test content structure using multidimensional scaling. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 2(2), 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, E., Mandl, C., Farny, S., & Salmivaara, V. (2020). Post-failure impression management: A typology of entrepreneurs’ public narratives after business closure. Human Relations, 74(2), 286–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C. J., & Neter, J. (2005). Applied linear regression models (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Lasio, V., Amaya, A., Espinosa, M. P., Mahauad, M. D., & Sarango, P. (2024). Global entrepreneurship monitor Ecuador 2023–2024. ESPAE, Escuela de Negocios de la ESPOL; UTPL. [Google Scholar]

- Liedholm, C. (2002). Small firm dynamics: Evidence from Africa and Latin America. Small Business Economics, 18(1), 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q., Li, N., & Fang, D. (2020). Framework for modeling multi-sector business closure length in earthquake-struck regions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M. I., Niehm, L. S., Sydnor, S. B., & Schrank, H. L. (2015). Predicting small business demise after a natural disaster: An analysis of pre-existing conditions. Natural Hazards, 79(1), 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, G. (2008). Firm closure, financial losses and the consequences for an entrepreneurial restart (Discussion Paper No. 08-094). ZEW—Centre for European Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, G. (2010). Business closure and financial loss: Who foots the bill? Evidence from German small business closure. ZEW—Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses. (n.d.). Business statistics. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/encuesta-a-empresas/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Nguyen, B. H., Pham, N. B. Q., & Do, T. H. H. (2023). Determinants of SMEs liquidation: Board heterogeneity and applicability of survival models. Studies in Economics and Finance, 40(1), 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, A. R. (1999). The demography of business closings. Small Business Economics, 12(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J. W. (2015). Best practices in logistic regression. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. A. (2016). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (6th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, D., & Gabrielsson, J. (2009). Entrepreneurs’ attitudes towards failure. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 15(4), 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, M. (2009). Defining business decline, failure and turnaround: A content analysis. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 2(1), a15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S., Midi, H. B., & Sarkar, S. K. (2010, March 23–25). Validation and performance analysis of binary logistic regression model. WSEAS International Conference on Environment, Medicine and Health Sciences, Penang, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Mendoza, R. L., & Aviles-Sotomayor, V. M. (2020). Las pymes en Ecuador. Un análisis necesario. 593 Digital Publisher CEIT, 5(5-1), 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, J. J. (2022). Positive business closure. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 3(2), 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, D., & Blackburn, R. (2002). Learning the hard way: The lessons of owner-managers who have closed their businesses. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 9(1), 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J., & Zhou, L. A. (2023). Can online consumer reviews signal restaurant closure: A deep learning-based time-series analysis. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 70(3), 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, H.-L., Ng, S.-S., Lim, Y.-H., Chong, T.-P., & Yip, Y.-S. (2023, October 12). Business closure and Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief: A conceptual framework. 10th International Conference on Business, Accounting, Finance and Economics (BAFE 2022), Kampar, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Flores, M. (2010). The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure and comparative optimism. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasileski, G., Rodríguez, H., & Diaz, W. (2011). Business closure and relocation: A comparative analysis of the Loma Prieta earthquake and Hurricane Andrew. Disasters, 35(1), 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yance Carvajal, C., Solís Granda, L., Burgos Villamar, I., & Hermida Hermida, L. (2017). La importancia de las Pymes en el Ecuador. Revista Observatorio de la Economía Latinoamericana. Available online: https://bit.ly/3Hp3hUB (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Yeboah-Assiamah, E., Hossain, F., Mamman, A., & Rees, C. J. (2023). On the question of entrepreneurial breakthrough or failure in Africa: A framework for analysis. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 14(2), 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).