Abstract

In this paper, we study how entrepreneurial and strategic processes develop in a public-sector organisation through a theoretical lens of Strategic Entrepreneurship (SE). Previous literature on SE practices identified a number of organisational aspects—such as organisational culture, structure, and entrepreneurial leadership—that are important to manage in order to benefit from new opportunities and strategic actions. So far, there is little knowledge about SE practices in the public sector and their possible consequences. There are also few qualitative studies in the field of SE, though arguments have been made for it. Our study is based on a longitudinal and qualitative process approach focusing on the work of the Swedish Public Employment Service’s (SPES) efforts to realise its new strategy through entrepreneurial and strategic processes. The results showed that there are several organisational tensions in relation to the processes of entrepreneurship. We have empirically contributed to previous literature by studying the SE practices of simultaneously balancing the processes of entrepreneurship and strategy. We have also contributed to a more nuanced discussion of the complexity of implementing SE practices and their relationship to organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership.

1. Introduction

Since the introduction of the concept of strategic entrepreneurship at the turn of the century, scholars have argued that it is important to understand strategic entrepreneurship (SE) practices, i.e., how organisations simultaneously balance entrepreneurial and strategic processes. Hence, it has been argued that SE practices have a direct effect on organisational performance (Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009). In line with this, scholars argue that SE practices are important for both the private (Ireland and Webb 2007; Kyrgidou and Hughes 2010; Luke et al. 2011) and public sectors (Höglund et al. 2018; Klein et al. 2013).

SE builds on previous research in entrepreneurship and strategic management, and is described as an interface between two key areas of research that offer new insights into public sector management (Kearney and Meynhardt 2016). If public organisations are to anticipate new problems and challenges, respond to them effectively and, at least to some degree, chart their own path towards the future, they need to think and act strategically and develop their ability to manage and control such outcomes (Poister 2010). Moreover, in this context, entrepreneurship can be of significant importance to public sector organisations as a means to enhance performance and add new aspects of value (Albury 2005; Moore 2005). Thus, public organisations are increasingly confronted with needs to innovate and to create different aspects of wealth, while still producing public value by delivering new or improved products and services (Boyne and Walker 2010; Lane 2008; Osborne 2010), and to become more effective (Albury 2005; Moore 2005).

Nevertheless, although entrepreneurship and strategic management over the last three decades are said to be of importance in the public sector (Kearney and Meynhardt 2016), there are few studies available that show how public organisations simultaneously balance strategic and entrepreneurial processes (Klein et al. 2013). Notable exceptions are Luke and Verreynne (2006), Klein et al. (2013) and Höglund et al. (2018), who clearly position their work within SE and explore the practices and possible challenges when introducing SE in the public sector. Most studies of the public sector tend to focus on either strategic management or entrepreneurship, not both, and how entrepreneurial and strategic processes are balanced. Consequently, there is little knowledge about SE practices in the public sector and its possible consequences (Klein et al. 2013; Höglund et al. 2018; Wright and Hitt 2017). SE as a research field also needs to incorporate alternative ways of understanding, i.e., instead of the traditional approach based on economic and positivist assumptions (Schindehutte and Morris 2009). In line with this, there are calls for more diversified views embracing, rather than excluding, different perspectives on SE (Kuratko and Audretsch 2009; Schindehutte and Morris 2009; Foss and Lyngsie 2012). However, until now few have responded to the calls, resulting in few qualitative studies.

It could be argued that key qualitative features of SE (e.g., newness, change, and renewal) are not subsidiary to quantities underlying financial performance (e.g., profit, revenues) or growth (e.g., new products). Rather, if qualitative features of SE are attained, the likelihood of a substantial payoff increases, even though this might not immediately be apparent (Schindehutte and Morris 2009). Therefore, there is a need to also focus on qualitative features of SE (Höglund 2015; Schindehutte and Morris 2009) insofar as such, an approach can provide a better understanding of the phenomenon of entrepreneurship in established organisations (Kuratko 2007).

To meet the call for more qualitative research within SE, we studied the Swedish Public Employment Services (SPES), a central agency in Sweden that in 2014 initiated a major reformation to improve daily operations, customer expectations and the transparency of the agency’s activities both internally and externally. Its overall strategic intention is stated in a new strategy, ‘The Renewal Journey’ (SPES 2015). An overarching goal of the strategy is to become a modern agency characterised by an entrepreneurial spirit that offers and delivers relevant service to its customers. The new strategy marks an attempt to turn away from what has been described as non-transparent, detailed, authoritarian and top-management-oriented governance. Now, the agency is facing new challenges, since its established administrative structures, routines and procedures, and not least cultural aspects have to be adjusted to the new features of the strategy, including an entrepreneurial spirit (Höglund et al. 2018).

The purpose of our study is to enhance our understanding of how strategic and entrepreneurial processes develop in a public sector organisation, as well as their possible challenges. To achieve this, we turned to the SE literature and developed the following research question: How are entrepreneurial and strategic processes balanced in a public sector organisation? In this way, we contribute to the strategic management literature on the public sector in general, and more specifically to the literature on SE.

The structure of the paper is six-fold. First, we discuss SE and its practices. Second, we describe a theoretical framework of organisational organisation, structure and entrepreneurial leadership in relation to SE practices. Third, we explain the method used in this paper. Fourth, we demonstrate and analyse the empirical context. Fifth, we discuss the results from the empirical analysis. Finally, we draw our conclusions and outline avenues for future research.

2. Strategic Entrepreneurship

Strategic Entrepreneurship (SE) can be viewed as a form of organisational entrepreneurship, taking place within existing organisations, that draws on the enterprising discourse and the ideas of the managerial entrepreneur (Höglund 2015). Thus, SE is strongly influenced by management through theories about entrepreneurship in established businesses, e.g., corporate entrepreneurship (Hjorth 2004). The umbrella term of corporate entrepreneurship is often comprised of two categories of phenomena: corporate venturing and SE. Kuratko and Covin (2015) argue that corporate venturing includes entrepreneurial processes in which new businesses are created, added to, or invested in by an established organisation, while SE focuses on a broader array of entrepreneurial processes that do not necessarily involve new businesses being added to the organisation. In line with this, Ireland and Webb (2009) state that SE is an important path through which corporate entrepreneurship manifests itself. Hjorth (2004) stresses that the attractiveness of this kind of managerial form of entrepreneurship lies in combining economics and behaviourism in the name of an enterprise, promising speed, flexibility and innovation. These are all aspects that are incorporated in the SE literature and are used as reoccurring arguments for engaging in SE practices (Ireland and Webb 2007; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009; Luke et al. 2011). It is a practice that several scholars have pointed out as a key differentiator regarding companies’ abilities to compete in markets characterised by uncertainties and rapid changes (Ireland and Webb 2007; Kyrgidou and Hughes 2010; Luke et al. 2011).

Moreover, SE can be seen as a practice that attempts to use entrepreneurship as a tool for management control by stimulating the employees to become self-leaders, i.e., individuals who are changeable, flexible, spontaneous, creative and passionate, while at the same time remaining in control (Höglund et al. 2018). Thus, SE is a practice that on the one hand attempts to use entrepreneurship as a tool for control by stimulating the individuals to follow their hearts and improvise, to be changeable, flexible, spontaneous, creative and passionate, i.e., to become an enterprising self; and on the other hand, use entrepreneurship as a way to vitalise and renew organisations (Hjorth et al. 2003). The aspects of management control are closely related to strategic activities of long-term planning, the preparation of decision-making, formal leadership, avoidance of risks and minimisation of mistakes (cf. Ireland and Webb 2007; Hjorth et al. 2003). The SE practices of letting entrepreneurial processes take place to bring about change and renewal, while at the same time managing administrative values of strategic management and control, is thus the primary focus. It is also this simultaneous balance of strategic and entrepreneurial processes, i.e., SE practices, that are described as challenging and need to be further addressed in the literature.

SE practices as a concept emerged at the turn of the 21st century as several researchers began noticing that organisations were trying to pursue strategic management processes while at the same time trying to embrace entrepreneurial processes. The ability to simultaneously balance strategic processes with entrepreneurial processes is what has been referred to as SE practices (Foss and Lyngsie 2012). Within this stream of literature, strategic processes are often described in terms of advantage-seeking or exploitation, while entrepreneurial processes are described in terms of opportunity-seeking or exploitation (Foss and Lyngsie 2012; Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009). Working with SE practices is considered challenging (Ireland and Webb 2007), as they are two quite different processes. Strategic processes focus on an organisation’s long-term development–deciding on the scope of operations, management and control of resources, and intended sources of competitive advantages (Ireland and Webb 2007). It is characterised by high levels of standardisation and fixed processes that reduce risk and enhance stability and economic efficiency (Ireland and Webb 2009). In contrast, entrepreneurial processes are all about finding new opportunities in the creation of change and newness within organisations, such as establishing new organisational units or organisations, or renewing existing ones (Kuratko and Audretsch 2009). Entrepreneurial processes focus on flexible structures, experimentation, innovation, and high risks of failure (Ireland and Webb 2009).

3. Theoretical Framework

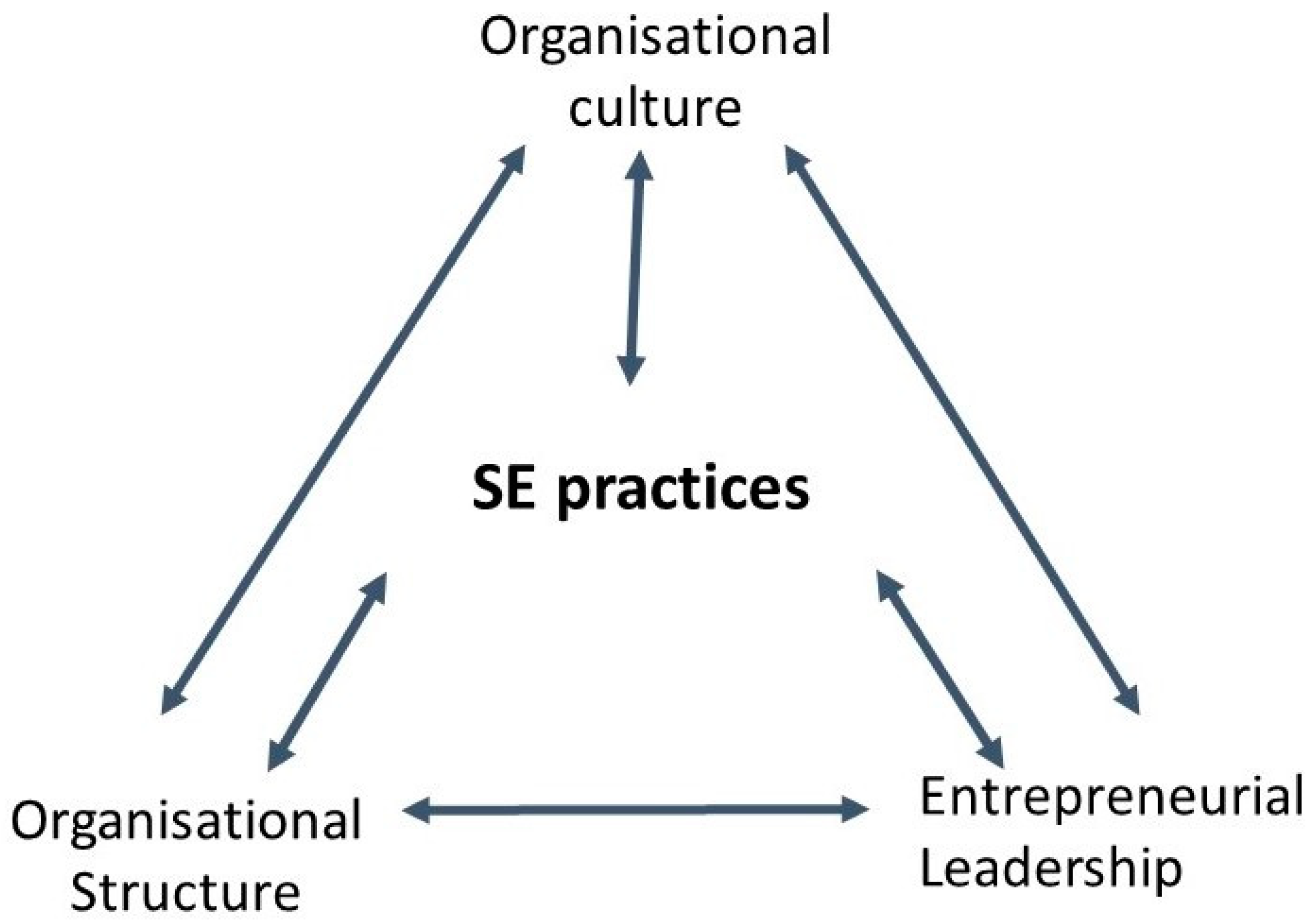

To meet the challenges of balancing strategic and entrepreneurial processes, previous research has shown that special consideration needs to be given to the relationships between structure, culture, and leadership. For example, Ireland and Webb (2007) were the first ones to explicitly talk about SE as a practice to balance strategic and entrepreneurial processes. They emphasised the importance of understanding SE practices in relation to operational, structural and cultural characteristics enabling efficient and effective SE. While organisational culture and structures are relevant to understand in regard to the boundaries of SE (Ireland and Webb 2009) in a public organisational context, the operational is of less interest as it focuses on mergers and acquisitions (cf. Ireland and Webb 2007). Rather, we would suggest, in line with Höglund et al. (2018), that we need to address the characteristics of entrepreneurial leadership in relation to SE practices. Also, Kuratko and Audretsch (2009) address the need to understand the boundaries of SE in relation to entrepreneurial leadership, as well as organisational culture and structure, as the structural and cultural mechanisms required to support entrepreneurship are different from the administrative structures, rules and procedures needed to support strategy, which can bring about several challenges (Ireland and Webb 2009). This will be elaborated on in more detail below.

3.1. Organisational Culture

There are many different definitions of culture with associated research fields where issues related to organisational culture are discussed. We will not delve further into these theories, as we will focus on how research within SE views organisational culture. Within SE, researchers point out (see, for example, Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007) that an organisational culture can be defined as a set of shared values (what is important) and beliefs (how things work) in the organisation that supports the organisation’s structural features and the organisational members’ actions to produce norms (how the work is carried out in the organisation).

When it comes to an entrepreneurial culture, it develops in an organisation whose leaders use entrepreneurial thinking, i.e., a growth-oriented perspective that advocates flexibility, creativity and continuous innovation in organisations (cf. Ireland et al. 2003, 2009; Ireland and Webb 2007; Morris et al. 2008). When it comes to culture, Ireland et al. (2003) argue, that an effective entrepreneurial culture is based on the commitment that is linked to creating new opportunities. This requires the organisation to stimulate and encourage behaviours that bring new ideas, creativity, learning and risk taking (Ireland and Webb 2009). However, failures must also be accepted. In this way, product and process development, as well as administrative innovations can be encouraged and continuous change is seen as a catalyst for new opportunities (Kuratko and Audretsch 2009).

3.2. Organisational Structure

Previous research on SE practices (see e.g., Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009) indicates the importance of the organisational culture being supported by structures. Researchers on SE often refer to structure not only as the formal organisational structure but also standardised procedures and formalised processes (see e.g., Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007; Morris et al. 2008). For example, Ireland and Webb (2007) emphasise that structure includes the degree of autonomy that managers and employees have (degree of decentralisation), how routinised the behaviours are (degree of standardisation) and how much written instruction there is regarding how the work should be accomplished (degree of formalisation). Decentralisation and a high degree of autonomy support entrepreneurial processes, while a centralised organisational structure with a high degree of standardisation and formalised ways of doing the work supports strategic processes (Höglund et al. 2018). From an SE perspective this becomes complex as you need to support both strategic and entrepreneurial processes.

In terms of structure and SE practices, Morris et al. (2008) state that, an organisational structure based on decentralisation of mandates, semi-standardised procedures and semi-formalised processes are needed. Entrepreneurial processes are supported by autonomy and facilitated with decentralised structures, while semi-standardised and semi-formalised routines and guidelines also will support management control and goal fulfilment (Ireland and Webb 2009). On the one hand, too much formalisation tends to stifle creativity among employees, but on the other hand some degree of formalisation of the decision rules used for guiding entrepreneurship is desirable, as it allows for the creation of knowledge-search routines that may potentially reduce the amount of financial and human capital inappropriately used or wasted (Ireland and Webb 2007). Put these aspects together and it becomes clear that this is a complicated balance, with the view of public organisations often being formalised, administrative and bureaucratic (cf. Osborne 2006).

3.3. Entrepreneurial Leadership

Similar to organisational culture, there are lots of different theories and views on organisational leadership. As before, we will not delve into these theories, but will turn directly to the SE literature to further understand the scholars’ take on leadership. Previously, research on SE practices tended to discuss entrepreneurial leadership, with the reasoning that most previous research tends to address leadership from a strategic management perspective. Entrepreneurial leadership brings together aspects of strategy, leadership, and entrepreneurship, and terms like ‘visionary’ and ‘strategic’ become important to study (Kuratko and Audretsch 2009). Being visionary falls into the realm of entrepreneurship, while strategic falls into strategic management. In other words, entrepreneurial leadership includes the ability to anticipate, envision, maintain flexibility, think strategically and work with others to initiate changes that will create a viable future for the organisation (see e.g., Kuratko 2007; Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009).

One problem, highlighted by Ireland and Webb (2007), is that employees and stakeholders prefer leaders who choose a consistent path, while entrepreneurship is based on change and innovation. Morris et al. (2008) address a similar problem as they emphasise that behaviours that stimulate new opportunities can be seen as unattractive to multiple stakeholders as they are experimental by nature and, therefore, include a great deal of uncertainty as to whether there will be any positive outcome. From a leadership perspective, such processes are very difficult to control. In order to create and adopt new opportunities, employees need to change and have the ability to adapt, and must cease using previous routines that they are likely to be more comfortable with (Ireland et al. 2003). This creates a situation where organisations prefer behaviours linked to strategic benefits and the use of existing procedures and routines.

4. Method

The study is based on a longitudinal and qualitative process approach focusing on the work of the Swedish Public Employment Service’s (SPES) efforts to realise its new strategy through entrepreneurial processes. The new strategy and its associated change programme is labelled, ‘The Renewal Journey’. The renewal journey at SPES is planned to take place between 2014 and 2021. So far, we have examined the period between 2014 and 2018, treating it as a case study. The case study approach is particularly suitable in a context of longitudinal research that tries to unravel the underlying dynamics of phenomena that play out over time (Siggelkow 2007).

The authors of this paper have been invited by the top management at SPES to follow and document the agencies’ work in the renewal journey. One hundred interviews have so far been held between the autumn of 2015 and 2018. Interviewees include the agency’s director general, top and middle management, first-line managers, officers, consultants and representatives from the ministry of employment and the board of directors. Table 1 presents a summary of the interviews. The interviews lasted between 30 and 120 min, with an average of 90 min, and were transcribed verbatim. To gain an understanding of values in an organisation, methods are required that allow research participants to talk about their experiences and what these experiences mean to them (Höglund et al. 2018). In 2017 we dedicated a significant amount of time to observing and participating in internal meetings, e.g., top management teams’ weekly meetings, seminars and training programmes. Detailed field notes were made at all the observations, and where possible we made recordings and verbatim transcriptions. To increase our understanding of contextual factors, we also collected and studied such documents as strategic plans, annual reports, press articles and government reports.

Table 1.

A summary of interviews.

The coding process can be described as the precursor to the analysis. While the coding is quite different from doing the analysis itself, as the goal is not to find results but to find a way to manage a large amount of text, it is quite common to work with different categories (Höglund et al. 2018; Phillips and Hardy 2002). The categories used during the coding process are based on the theoretical framework of SE and the categories of organisational culture, organisational structure, and entrepreneurial leadership. In the first step, every instance of the transcribed text and field notes that could be categorised into one of the three categories were copied into a document. At this stage, it was important to be as inclusive as possible. In the second step we started to construct a narrative in relation to the three categories by iteratively analysing the empirical material, using the SE literature as a means to understand it.

5. Case Study: The Swedish Public Employment Service

The Swedish Public Employment Service (SPES) is a national public agency in Sweden with 320 local employment offices across the country and is led by a director general. It has approximately 14,500 employees. The Swedish parliament and the government provide its mission, long-term objectives and tasks. The overall goal is to facilitate matching between jobseekers and employers, with special priority given to jobseekers who, for a variety of reasons, have particular difficulties in finding employment. SPES is responsible for ensuring that unemployment insurance schemes are effectively used as transition insurances between jobs. Moreover, it is responsible for coordinating efforts to integrate newly arriving immigrants into the labour market. Finally, the agency’s tasks also include vocational rehabilitation, in collaboration with other agencies, to help individuals with limited work capacity due to disability or illness to be reintegrated into the labour market.

SPES has been heavily criticised during the past few decades, a fact that has increased pressure to change. Externally they have been criticised by the media and the government for their inadequate management and control, and for the lack of trust among both citizens and customers (SAPM 2015). Former management and control are described to have been authoritative, detail-driven, top-down, and non-transparent (SPES 2015). Consequently, politicians have demanded a change (Appropriation Letter 2013, 2014). In the next part of the paper we address issues of culture, structure and leadership at SPES from an SE perspective.

5.1. Organisational Culture

It has been documented both internally (SPES 2014, 2015) and externally (cf. SAPM 2016) that the culture within the agency was not well functioning. In short, the previous culture was described in terms of a management and control structure based on micromanagement, non-transparent, authoritarian, top management-oriented management style that resulted in a punitive work culture. As a result, when a new director general was appointed in 2014, its first mission was to set a new strategy that could steer the agency towards a new culture based on entrepreneurial processes of proactivity, creativity and flexibility. After several months of intense work, a new strategy, ‘The Renewal Journey’, was set by the top management team and it was approved by the board.

During the first phase of the renewal journey a lot of work was devoted to cultural aspects. The goal was to change the culture to become more entrepreneurial. One way of doing this is through the implementation of new core values, which will guide the employees in how they relate to each other and to the outside world. Employees at SPES are to be guided by the three following values: professional, inspirational and trustworthy.

The empirical material shows that there were high expectations at all management levels that the renewal journey would solve previous shortcomings related to the previous culture of management and control. By introducing the new strategy, the agency is supposed to succeed in becoming a modern central agency that encourages self-leadership, develop better qualified managers, makes employees more proactive and engaged, decreases regulatory structures and thus enhances room for employee action, customer-specific and digitalised services. However, as the pressure for results and tangible output solidified, the management felt there were challenges to fully embracing the entrepreneurial culture.

For example, external factors such as the Ministry of Employment and the board expect SPES to embrace the entrepreneurial aspects of the new strategy, but at the same time deliver tangible results. For instance, the Ministry of Employment expects the agency to be more proactive, flexible and take more matters into their own hands, as SPES has been given an enhanced scope for action as stated in the appropriation letter from the government. In the same vein, the Minister for Employment states in several of her speeches to managers and employees at SPES that the agency should be entrepreneurial by ‘pushing the limits’ and that the agency should ‘dare to renew’.

However, neither representatives from the Ministry nor the board are pleased with the agency and its management team regarding their ability to deliver tangible output and detailed strategies for its operation. For example, representatives from the board state that SPES must show a better administrative culture of ‘order and clarity’ and more detailed and informative reports regarding output. A manager at the ministry of employment said:

I think a cultural change in a central agency cannot be a goal in itself, it must be linked to output improvement. […] The metaphor of the renewal journey is tricky in a way. I think there are grounds for renewal and change of culture, but a journey? A development of an authority and its work cannot have a clear end. It must be continuing and you cannot wait until the end of the journey for the output. […] The output must be delivered at the same time [as working with the renewal journey]. I have a problem in separating the culture from output as they go together.

One aspect that several mangers, at all levels, expressed is their concern that the time for working with the cultural aspects of the renewal journey has decreased at the expense of reporting output. For example, one of the first-line managers expressed a concern that the quest for output will steer the agency in the wrong direction and that SPES need to redefine what output is in relation to the new strategy:

I think that the cultural change means that you need to require output in a different way than you have done before. But you do not! It is the same as before we began to speak about the cultural change. This is not in line with the renewal journey.

One part of the entrepreneurial culture is to give managers and officers at regional and local levels an enhanced scope for action to decide what needs to be done and how, based on overall objectives, regulations and local conditions. This means, among other things, that operational planning now has a more central role. One dilemma though, expressed by several of the first-line managers, is that the middle managers tend to stop any proactive and creative suggestion or action that will ‘push the limit’, i.e., in total opposition to the new strategy. Most of the middle managers state that they are positive towards the new entrepreneurial culture that includes an enhanced scope for action for the first-line managers and themselves. Despite this, when it comes to applying the strategy in practice there is still a (strong) tendency to go back to previous habits and behaviours of management and control through e.g., micromanagement. One of the top managers expressed a concern that several of the managers, at all levels, are still concerned and afraid that if they do something wrong, they will be punished. Similarly, one of the middle managers expressed that:

As a manager, it is important to show that making a mistake is not the end of the world. Instead, one can learn from it and move on and become confident and strengthened by it. If there is too much micromanagement, you will stop using your brain.

The same conclusion is made by representatives from the Ministry of Employment, i.e., that managers and employees for the last decade have been driven by a fear of making mistakes. One of the interviewed representatives explained that this is due to the ‘old’ culture, however; the interviewee argued that there is sufficient competence among the employees at SPES and they do know where the limits are and what can be done within the boundaries and hence, there is room for some experimenting of new ideas and doing of tasks.

5.2. Organisational Structure

To support the cultural aspects of the renewal journey, the top management team has developed and implemented a number of structural changes. During 2014 and 2015 the focus of the renewal journey was mainly on changing the behaviours of the employees towards a more entrepreneurial culture. The structural changes during this time were mainly related to changes within the top management team, e.g., from a reduction of the number of the members within the top management team, to the introduction of two new hierarchal levels, to a reconstruction of the market areas into three regions and to a cut of the number of local offices. At interviews and observation, it is mostly these structural changes that employees refer to, not the cultural changes.

The agency also mass-recruited new first-line managers, as an attempt to delimit the number of employees they are responsible for at operational level. This structural change in particular has been described as a way to reduce the distance between management and employees. However, most of the interviews show that, on the contrary, the new levels of management teams and the recruitment of more managers rather created ‘non-present managers’ and, therefore, it did not have the desired effect. One example our informants gave of ‘non-present managers’ is that first-line and middle managers are present at the office only a couple of days a week, as they are mostly in meetings with other managers or with outside actors in different collaboration projects. A middle manager said:

A manager attends meetings, that’s what he does. In order to better support the renewal journey and the quest for a more entrepreneurial culture, the top management team decided in the autumn of 2016 to introduce structural changes to support and to accelerate the cultural changes.

One of the top managers said:

We started the renewal journey as a ‘cultural journey’, but now I think we are in the process that we need to push the cultural journey forward by introducing structural changes. (Observation field notes)

After several months of work in smaller groups of top managers, new structural changes were launched as ‘the organisational rejuvenation’ in spring 2017, including a new business logic and a new organisation structure based on three business areas: specialisation, resource allocation, and structures, aiming support digitalisation and seamless customer flows, etc. The suggested organisational changes are described as radical and referred to the fact that the SPES needed to take a ‘quantum leap’ from one dimension to another (SPES 2017, p. 6). Moreover, that the opportunities that come with the ‘digital revolution’ are what make it possible to make these structural changes.

When the top management presented the structural changes to the Ministry of Employment and the board, they did not get the approval needed to carry out their plans for making the agency more modern and more digitalised to support the entrepreneurial culture. For example, the Ministry of Employment and the board addressed a concern regarding the need for a better risk analysis, as the ‘organisational rejuvenation’ is quite extensive and includes a lot of risk-taking in terms of being able to deliver output. A board member expressed it in the following way:

We do not believe that SPES can afford to lose delivery capacity at the present time; they do not have that position. It’s quite taxing to make an organisational change and it takes quite a lot of strength, with major risks associated with it.

Another concern was raised by both the Ministry of Employment and the board in regard to an impression that the organisational rejuvenation was not very well defined and developed in terms of how the changes are to be implemented. They also raised concerns as they interpreted the suggested changes as being too radical to implement all at once; rather, they suggested that the changes should be implemented more incrementally. In relation to this, some of the members of the top management team felt their scope for action was reduced and they were being micromanaged. In other words, the top management team could not act themselves in line with the entrepreneurial spirit of the renewal journey.

So far, the organisational rejuvenation has focused mainly on the structural changes and the processes of digitalisation as a way to support the renewal journey by creating structures for ‘the digital personal meeting’, which means going from a previous local autonomy to a national centralised function with only a few national offices. This change is described as fundamental and radical, and therefore, it needs to be incrementally implemented to enhance its possible success (SPES 2017). A top manager argued that:

We will have a national function for the digital personal meeting. We will have a customer perspective. We will develop our channels so the customer can contact us in a much more qualified way than through the personal, physical meeting. [...] An important channel for our customers to come in contact with us in the future will be the personal physical meeting at the employment office and on the web where we have our self-service, and a third channel is the personal digital meeting. They [the customer] will be able to meet us by phone, chat, via digital and get a personal meeting there.

During interviews, some managers raised a concern that the change towards ‘the digital personal meeting’ might create challenges as the officers usually handle their own cases and the digitalisation of the personal meeting will change this. Interviewees stressed that this change will force the officer to give up the right to ‘owning’ a customer. Thus, the officers might lose some scope for action as they will no longer be the main source of information and the main channel for the customer to receive support at the agency.

Previously, the officers could, more or less in collaboration with the customer, design necessary actions that were needed for the customer. With the suggested new structure, depending on the channel the customer chose, i.e., self-service, the digital channel, or the local office, the customer will meet different officers. In practice, this means that potentially several officers will help a customer to design and support required actions. This in turn will put a lot of pressure on the information systems, as the same information about the customer has to be available for the operational officers despite what channel the customer decided to use.

5.3. Entrepreneurial Leadership

At the yearly event for all managers, ‘Manager Days’, in 2017 the Minister for Employment stated the following in her speech:

Leadership means so incredibly much now. It is like a balance. One can say the glass is half-full or half-empty. But it is also about hope and despair. Should we dare to take on the difficult challenges? Is it worth rolling up our sleeves, or should we lean back and say that it may not go our way and continue as we always have? […] How to get the best out of the staff, of their organisation, is so incredibly important. I trust you. That’s how it is.

In documents as well as in interviews, SPES staff state that new insights and past experiences have led SPES to develop a new leadership philosophy that was launched in 2014. The official webpage states that:

SPES acts in a world that is becoming increasingly complex and is changing rapidly. Therefore, it is important that each one of us can lead her/himself towards the agency’s overall goal. This will make SPES as a whole more successful.

An important part of the new leadership philosophy is the idea of self-leadership. Self-leadership should be a cornerstone of the leadership on all levels of the agency. To fulfil the new philosophy, managers on all levels, as well as all employees, should exhibit five dimensions of leadership in the performance of his or her tasks. The five dimensions are: (1) to be a role model representing the agency’s values, (2) to describe the overall purpose of the organisation, (3) to challenge and question established routines, (4) to facilitate extended scope for action, and (5) to encourage and make people visible. Self-leadership means that everybody at SPES should take a responsibility for their actions, whether they are managers or employees. This is based on an idea that each and every individual can link their own inner motivation to an understanding of common organisational values and goals.

The managers and the leadership philosophy are put forward as the most important aspects of continuing the renewal journey and the organisational rejuvenation. A document (SPES 2017, p. 45) explaining the agency’s new organisation says:

An implemented leadership philosophy is the basis for successful organisational change if the new organisation is to function optimally. The five dimensions of leadership create both the security and power that will bring SPES into the new business logic. The importance of taking responsibility for the whole and creating internal partnerships is crucial for the balance between autonomous organisational components and the agency’s overall strategic management.

Therefore, far major efforts have been made to implement the leadership philosophy, e.g., through the training of almost 900 managers. The aim is to change behaviours related to the former, no-longer-desired, leadership culture. The first phase of the leadership training programme was provided by external management consultants through a so-called waterfall method, meaning that the management consultants started to work with top management, moving along to middle management and then to first-line operative managers. This means that the training programme took a top-down perspective where most of the training hours were dedicated to top and middle management. Other employees, such as the local officers who help employment seekers find new jobs, were not offered the formal training programme; instead they were trained by their manager. One of the top managers reflected on this as follows:

An important effort was made to work with leadership, i.e., self-leadership, and we have also worked with our management teams throughout the entire organisation. It is clear that this work continues, albeit with reduced efforts by external consultants. It’s our ambition, hope and belief that this work of renewal is going on continuously in the organisation, with the support of our managers, but the goal of the whole renewal journey has not yet been reached.

So far there are many different interpretations of the leadership philosophy and the term self-leadership. In the beginning of 2015 and 2016, there were several interpretations among managers and employees, according to our interviews and observations. One such interpretation is that self-leadership might imply that one can do as one pleases and hence can experiment in an entrepreneurial spirit that sometimes goes beyond the boundaries of the vision, goals and strategic directions of SPES. An employment service officer stated the following about self-leadership:

What does it mean? That we lead ourselves? We already do this in our daily work, but is this self-leadership? So far, I have no idea.

In late 2016 and early 2017, the picture seems to have changed and a more common view about what self-leadership is and how it can be used emerged. One explanation for this is that several management and control tools have been linked to the five dimensions of the leadership philosophy, e.g., appraisal talks and the evaluation of performance tools.

6. Result Discussion

In the literature on SE practices, researchers (see e.g., Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009) tend to define an organisational culture as a set of shared values (what is important) and beliefs (how things work) in the organisation that supports the organisation’s structural features (e.g., centralisation or decentralisation) and the organisational members’ actions to produce norms (how the work is carried out in the organisation). If we put this in relation to SPES and their renewal journey, our results show that all managers and employees agree on the need to leave the past and the previous punitive work culture based on the ideas of micromanagement with extensive performance reporting and monitoring. It has been documented both internally (SPES 2014, 2015) and externally (cf. SAPM 2016) that the culture within SPES was not well functioning. One way to make up with the past culture was to abandon the required performance reporting and implement new core values built on the keywords: professional, inspirational and trustworthy. These values are to guide the work of SPES employees and are expected to help the agency transform its culture to embrace more entrepreneurial processes. Top management has also initiated extensive training programmes to change the culture and to implement the new philosophy of self-leadership with the hope of moving the agency towards becoming more entrepreneurial. Processes of entrepreneurship require a high degree of autonomy, and this has created some tension in the organisation. For example, when the board and government started questioning the performance at SPES and the lack of tangible results, this led to the agency once again starting to work with performance measurements, a practice that SPES had tried to eliminate by implementing the Renewal Journey. This change in work practice will have a direct effect on organisational structure as the organisational culture and structure need to be congruent (see e.g., Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009).

Hence, organisational structure is about the degree of autonomy that managers and employees have (degree of decentralisation), how routinised the behaviours are (degree of standardisation) and how much written instruction there was regarding how the work should be accomplished (degree of formalisation) (Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009). The previous punitive culture is described as being a result of micromanagement, where a centralised organisational structure emphasised top management, hierarchy, and management control by formalised performance monitoring and reporting. These structures were not aligned with the new organisational culture or the ideas of self-leadership. As a result, it created a lot of tension in the organisation and obstructed many of the entrepreneurial initiatives of being creative, proactive and flexible. As such, entrepreneurial processes need structures of decentralisation and a high degree of autonomy (c.f. Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009). In the later phase of the Renewal Journey, top management realised they had to start working to also change the organisational structures if they wanted to go forward with the implementation of the Renewal Journey. In spring of 2017 a programme called ‘the organisational rejuvenation’ was launched, including a new business logic, a new organisation structure based on three business areas—specialisation, resource allocation and structures—that aimed to support digitalisation and seamless customer flows. It is too early to say if the new organisational structure will better support an entrepreneurial culture and the strategy of the renewal journey, but the empirical material shows some potential challenges. For example, the officers’ scope for action was reduced by the new customer channel of ‘the digital personal meeting’ and the idea of a national centralised function. The new structure does not seem to address the issue of non-present managers. Since the managers are to serve as cultural-change agents, this could be a significant challenge.

Our results show not only how organisational culture and structure need to support each other in order to succeed with the strategic work and the implementation of the Renewal Journey, they also show the importance of addressing the question of leadership. This paper shows that the entrepreneurial leadership needs support to succeed with strategy work. Entrepreneurial leadership in the SE perspective includes the ability to anticipate, envision, maintain flexibility, think strategically and work with others to initiate changes that will create a viable future for the organisation (Kuratko 2007). In order to lead and act in this way, there has to be a culture that understands the value of entrepreneurial processes, not only strategic processes; there must also be supportive structures that allow autonomy. Before the renewal journey at SPES, management control was based on micromanagement, where the managers and employees had a low degree of autonomy as they were controlled and monitored by performance measurements. SPES tried to replace that leadership style with the new philosophy of self-leadership, which can be understood as entrepreneurial leadership (Höglund et al. 2018). Everybody, managers as well as employees, must be self-leaders and exhibit five dimensions of leadership in the performance of their tasks: (1) to be a role model representing the agency’s values, (2) to describe the overall purpose of the organisation, (3) to challenge and question established routines, (4) to facilitate extended space for action, and (5) to encourage and make people visible. These five dimensions of leadership become important not only for changing cultural behaviours, but also in the making of semi-structures that support SE practices (cf. Ireland and Webb 2007). Moreover, these dimensions of leadership have the potential to link both entrepreneurial and strategic activities. As Ireland et al. (2003) argue, effective entrepreneurial leaders create value for the organisation by being strategically entrepreneurial through leaders who embrace an entrepreneurial mind-set that helps them to develop a culture in which resources are managed and controlled strategically, yet entrepreneurially.

In summary, the SE literature shows that if an organisation wants to implement a strategy that includes the SE practices of simultaneously balanced entrepreneurial and strategic processes, it must understand SE practices in relation to the organisation’s culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership (Ireland et al. 2003; Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009; Höglund et al. 2018). Our case study supports these observations. We could see that SPES struggled to align its organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership with SE practices. In the beginning of the Renewal Journey at the agency, the strategy was to focus on changing the behaviours of the managers and employees by changing the previous punitive culture built on micromanagement. A lot of effort was put into introducing new core values and a new leadership philosophy of self-leadership. However, a couple of years into the Renewal Journey, the top management realised that the process of changing the culture and people’s behaviours was taking too long if they wanted to achieve their goal by 2021. One of the problems they saw was that the organisational structures did not support the new strategy, and as a result they introduced the organisational rejuvenation programme. This is how SPES tried to work towards aligning its organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership. Thus, our case indicates the importance of organisations not only understanding organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership in relation to SE practices, but also understanding that each part must be aligned and mutually supportive. This suggests that there is a complex interaction that needs to be addressed to succeed with the implementation of a new strategy that includes SE practices of simultaneously balanced entrepreneurial and strategic processes. One must understand SE practices in relation to the alignment of organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership to be mutually supportive; see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Strategic Entrepreneurship (SE) practices and their relationship to organisational culture, structure, and entrepreneurial leadership.

7. Conclusions

Although entrepreneurship and strategic management are said to be of importance for the public sector, there are hardly any studies that consider studying both processes (Wright and Hitt 2017). Instead, most studies of the public sector tend to focus on either strategy or entrepreneurship, not both (Höglund 2015). Even fewer study the practice of simultaneously balancing entrepreneurial and strategic processes in the public sector (Klein et al. 2013). Consequently, there is little knowledge about SE practices in the public sector and their possible consequences (Höglund et al. 2018). There are also few qualitative studies within SE, despite observations that key features of SE, such as newness, change and renewal, are better understood qualitatively than through quantities of financial performance or growth (Schindehutte and Morris 2009). As argued in the introduction, there is a clear need to focus on the qualitative features regarding the generation of empirical material (Höglund 2015) insofar as such an approach can provide a better understanding of the phenomenon of entrepreneurship in established organisations (Kuratko 2007) and SE (Schindehutte and Morris 2009). This paper was an attempt to address this, and we would like to suggest that future research look into this as well, as the need to further understand the qualitative aspects of SE practices is growing, especially in a public-sector context (Höglund et al. 2018). There is a need for more empirical studies on how entrepreneurial and strategic processes are balanced in public organisations, as both entrepreneurship and strategy have become such a vital part of reforming public organisations.

By contributing with a longitudinal and qualitative process approach, focusing on the work of the SPES’s efforts to realise its new strategy through strategic and entrepreneurial processes, we have not only contributed empirical descriptions, but also enhanced our understanding of the complexity of working with SE practices in public organisations that tend to be quite administrative, bureaucratic and hierarchical; all these aspects create tensions with entrepreneurial processes. Our results show how a public organisation tries to reposition itself and gain the citizens’ and society’s trust by using entrepreneurship as a strategic management tool for renewal. This renewal effort brings on challenges related to the SE practices of simultaneous balancing processes of entrepreneurship and strategy.

Previous literature (Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Kuratko and Audretsch 2009; Höglund et al. 2018) on SE, as well as our results, show that organisations that implement SE practices need to do so in relation to their organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership. However, our results show that the complexity is much greater than previously explained or accounted for in the SE literature. They suggest that one not only needs to understand organisational culture, structure and entrepreneurial leadership in relation to SE practices, but that they must also be aligned and mutually supportive, see Figure 1. If we take this complexity a step further, this means that you can’t choose to work with either the organisational culture or structure or entrepreneurial leadership individually, or start with one and move along to the next one, as they are all dependent upon one another to succeed with the implementation of SE practices. This issue has not been explicitly addressed in previous literature to our knowledge, but could be of significant importance to managers and employees working in public organisations to implement entrepreneurial and strategic processes.

Lastly, we would like to address a concern regarding the implementation of entrepreneurial processes in the public sector and the possible consequences of an enterprising approach that accompanies SE practices. Using entrepreneurship as a strategic management tool for renewal, and stimulating the managers and employees to become self-leaders, i.e., individuals/leaders who are changeable, flexible, spontaneous, creative and passionate, as a way to revitalise ageing structures and renew the organisation (cf. Hjorth et al. 2003; Höglund et al. 2018), challenges values of the public sector, such as democracy, accountability, and equal treatment. For example, the ideas of entrepreneurial leadership can be described in terms of neo-liberalistic ideas of the human being as an enterprise, i.e., the enterprising self, which builds on the idea of individuals acquiring and exhibiting more ‘market-oriented’, ‘proactive’, ‘empowered’ and ‘entrepreneurial’ attitudes, behaviours and capabilities (du Gay et al. [1996] 2005; Höglund 2015). Hjorth et al. (2003) state that the ideas of enterprising selves and the pressure of being proactive, responsible and initiative-takers have become widespread in society, in everyday life as well as in the public sector. As a result, there has been an enhanced focus on the self-manager, the opportunity seeker, and the innovative risk manager who is a driver of customer focus. This means that, for example, public values of equal treatment are being challenged as the entrepreneurial leadership stimulates proactivity—taking things into your own hands—and being creative in meeting customer demands, all of which results in different work practices towards the customer, ending up with the customers getting different services that in turn will affect their opportunities for equal treatment. We could, in other words, discuss the appropriateness of such ‘enterprising’ behaviour in a context of the public sector, and a small, but growing, number of researchers are questioning how entrepreneurship can be used in the public sector without hampering basic ideals such as accountability, equal treatment and democratic values (Axelsson et al. 2018; Höglund et al. 2018). We would like to encourage further research within this vein.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Swedish Employment Service.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Albury, David. 2005. Fostering Innovation in Public Services. Public Money and Management 25: 51–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appropriation Letter. 2013, Regleringsbrev för Budgetåret 2013 Avseende Arbetsförmedlingen [The Swedish Employment Service Appropriation Letter for the Budget Year of 2013].

- Appropriation Letter. 2014, Regleringsbrev för Budgetåret 2014 Avseende Arbetsförmedlingen [The Swedish Employment Service Appropriation Letter for the Budget Year of 2014].

- Axelsson, Karin, Linda Höglund, and Maria Mårtensson. 2018. Is what’s Good for Business Good for Society? Entrepreneurship in a School Setting. In The Dynamics of Entrepreneurial Contexts: Frontiers in European Entrepreneurship Research. Edited by Ulla Hytti, Robert Blackburn and Silke Tegtmeier. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Boyne, George A., and Richard M. Walker. 2010. Strategic Management and Public Service Performance: The Way Ahead. Public Administration Review 70: S185–S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Gay, Paul, Graeme Salaman, and Bronwen Rees. 2005. The Conduct of Management and the Management of Conduct: Contemporary Managerial Discourse and the Constitution of the “Competent” Manager’. Journal of Management Studies 33: 263–82. Edited version, 2005, 40–57. First published 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, Nicolai, and Jacob Lyngsie. 2012. Strategic Entrepreneurship: An Emergent Approach to Firm-Level Entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Organizational Entrepreneurship. Edited by Daniel Hjorth. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., pp. 208–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth, Daniel. 2004. Creating Space for Play/Invention–Concepts of Space and Organizational Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development: An International Journal 16: 413–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, Daniel, Bengt Johannisson, and Chris Steyaert. 2003. Entrepreneurship as Discourse and Life Style. In The Northern Lights–Organization Theory in Scandinavia. Edited by Barbara Czarniawska and Guje Sévon. Malmö: Liber Ekonomi. [Google Scholar]

- Höglund, Linda. 2015. Strategic Entrepreneurship–Organizing Entrepreneurship in Established Organizations. Lund: Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Höglund, Linda, Mikael Holmgren Caicedo, and Maria Mårtensson. 2018. A Balance of Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship Practices–the Renewal Journey of the Swedish Public Employment Service. Financial Accountability and Management 34: 354–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R. Duane, and Justin W. Webb. 2007. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating Competitive Advantage through Streams of Innovation. Business Horizons 50: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R. Duane, and Justin W. Webb. 2009. Crossing the Great Divide of Strategic Entrepreneurship: Transitioning between Exploration and Exploitation. Business Horizons 52: 469–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R. Duane, Michael A. Hitt, and David G. Sirmon. 2003. A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and its Dimensions. Journal of Management 29: 963–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R. Duane, Jeffery G. Covin, and Donald F. Kuratko. 2009. Conceptualizing Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33: 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, Claudine, and Timo Meynhardt. 2016. Directing Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy in the Public Sector to Public Value: Antecedents, Components, and Outcomes. International Public Management Journal 19: 543–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Peter G., Joseph T. Mahoney, Anita M. McGahan, and Christos N. Pitelis. 2013. Capabilities and Strategic Entrepreneurship in Public Organizations. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 7: 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, Donald F. 2007. Corporate Entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship 3: 151–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuratko, Donald F., and David B. Audretsch. 2009. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Exploring Different Perspectives of an Emerging Concept. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 33: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, Donald F., and Jeffery G. Covin. 2015. Forms of Corporate Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgidou, Lida P., and Mathew Hughes. 2010. Strategic Entrepreneurship: Origins, Core Elements and Research Directions. European Business Review 22: 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Jan-Erik. 2008. Strategic Management for Public Services Delivery. The International Journal of Leadership in Public Services 4: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, Belinda, and Martie-Louise Verreynne. 2006. Exploring Strategic Entrepreneurship in the Public Sector. Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management 3: 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, Belinda, Kate Kearins, and Martie-Louise Verreynne. 2011. Developing a Conceptual Framework of Strategic Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 17: 314–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Mark H. 2005. Break-Through Innovations and Continuous Improvement: Two Different Models of Innovative Processes in the Public Sector. Public Money & Management 25: 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Michael H., Donald F. Kuratko, and Jeffrey G. Covin. 2008. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Mason: South Western. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, Stephen P. 2006. The New Public Governance? Public Management Review 8: 377–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, Stephen P. 2010. Delivering Public Services: Time for a New Theory? Public Management Review 12: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Nelson, and Cynthia Hardy. 2002. Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction. Qualitative Research Methods Series 50; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Poister, Theodore H. 2010. The Future of Strategic Planning in the Public Sector: Linking Strategic Management and Performance. Public Administration Review 70 Suppl. 1: 246–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAPM. 2015. Att Styra mot ökat Förtroende–är det Rätt väg? [Governance towards Improved Trust–Is It the Right Way?]. Stockholm: Statskontoret [The Swedish Agency for Public Management]. [Google Scholar]

- SAPM. 2016. Tillitsbaserad Styrning i Statsförvaltningen. Kan Regeringskansliet visa Vägen? [Trust-Based Management Control in State Administration. Can the Government Office Show the Way?]. Stockholm: Statskontoret [The Swedish Agency for Public Management]. [Google Scholar]

- Schindehutte, Minet, and Michael H. Morris. 2009. Advancing Strategic Entrepreneurship Research: The Role of Complexity Science in Shifting the Paradigm. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33: 241–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj. 2007. Persuasion with Case Studies. Academy of Management Journal 50: 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPES. 2014. Arbetsförmedlingens Årsredovisning [Annual Report–The Swedish Public Employment Service]. Stockholm: Arbetsförmedlingen [The Swedish Public Employment Service]. [Google Scholar]

- SPES. 2015. Arbetsförmedlingen 2021–Inriktning och Innehåll i Myndighetens Förnyelseresa [The Swedish Public Employment Service 2021–Direction and Content of the Agency’s Renewal Journey]. Stockholm: Arbetsförmedlingen [The Swedish Public Employment Service]. [Google Scholar]

- SPES. 2017. Arbetsförmedlingens Organisation–Verksamhetslogik, Organisation och Resursfördelning–Riktlinjer och Utgångspunkter till tre Delutredningar [The Organisation of the Swedish Public Employment Service–Business Logic, Organisation and Resource Allocation–Direction and Starting Points for Three Sub-Studies]. Stockholm: Arbetsförmedlingen [The Swedish Public Employment Service]. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Mike, and Michael A. Hitt. 2017. Strategic Entrepreneurship and the SEJ: Development and Current Progress. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 11: 200–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).