Palliative Care in High-Grade Glioma: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Approach

2.1. Supportive Care Needs of HGG Patients: Symptoms, Functional Impairments, and Distress

2.2. Caregiver Needs

2.3. Advance Care Planning

2.4. End of Life

2.5. Primary and Specialty Palliative Care for High-Grade Glioma

2.6. Specialty Palliative Care

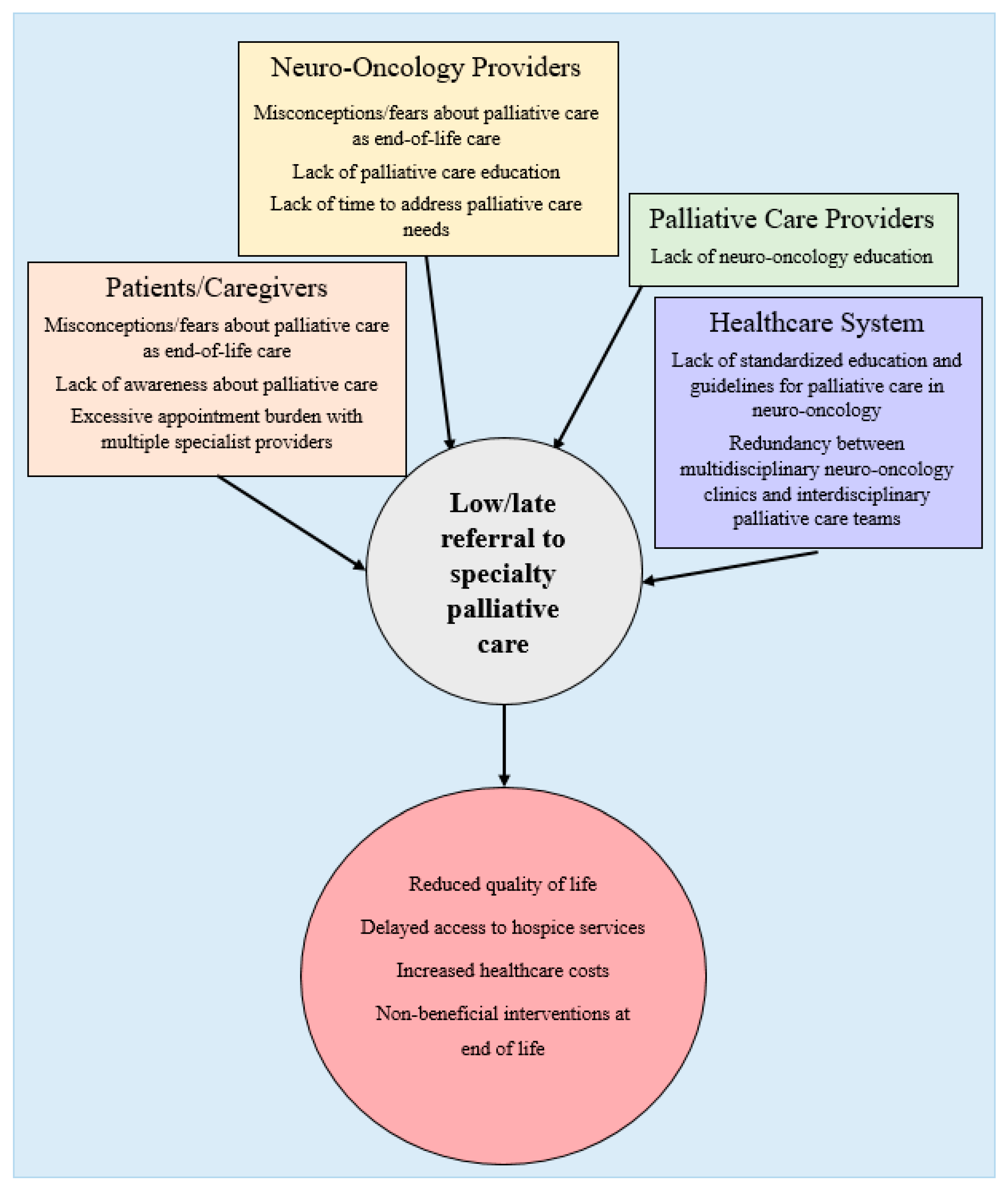

2.7. Challenges in Integrating Palliative Care for Neuro-Oncology

2.8. Future Directions

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Stetson, L.; Virk, S.M.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Epidemiology of Gliomas. Cancer Treat. Res. 2014, 163, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society. 2019. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Liu, Y.; Tyler, E.; Lustick, M.; Klein, D.; Walter, K.A. Healthcare Costs for High-grade Glioma. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, L.M.; Cui, Z.; Wu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Gaynor, P.J.; Oton, A.B. Current and projected patient and insurer costs for the care of patients with non-small cell lung cancer in the United States through 2040. J. Med. Econ. 2017, 20, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.; Catt, S.; Chalmers, A.; Fallowfield, L. Systematic review of supportive care needs in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro-Oncology 2012, 14, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. Definition of Palliative Care. 2019. Updated 29 January 2019. Available online: https://www.capc.org/about/palliative-care/ (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakitas, M.; Lyons, K.D.; Hegel, M.T.; Balan, S.; Brokaw, F.C.; Seville, J.; Hull, J.G.; Li, Z.; Tosteson, T.D.; Byock, I.R.; et al. Effects of a Palliative Care Intervention on Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Advanced Cancer. JAMA 2009, 302, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.S.; Penrod, J.D.; Cassel, J.B.; Caust-Ellenbogen, M.; Litke, A.; Spragens, L.; Meier, D.E. Cost Savings Associated With US Hospital Palliative Care Consultation Programs. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1783–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, D.P.; LeBrett, W.G.; Bryant, A.K.; Bruggeman, A.R.; Matsuno, R.K.; Hwang, L.; Boero, I.J.; Roeland, E.J.; Yeung, H.N.; Murphy, J.D. Effect of Palliative Care on Aggressiveness of End-of-Life Care Among Patients With Advanced Cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 13, e760–e769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Temel, J.S.; Temin, S.; Alesi, E.R.; Balboni, T.A.; Basch, E.M.; Firn, J.I.; Paice, J.A.; Peppercorn, J.M.; Phillips, T.; et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pace, A.; Dirven, L.; Koekkoek, J.A.F.; Golla, H.; Fleming, J.; Rudà, R.; Marosi, C.; Le Rhun, E.; Grant, R.; Oliver, K.; et al. European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guidelines for palliative care in adults with glioma. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e330–e340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piil, K.; Jakobsen, J.; Christensen, K.B.; Juhler, M.; Jarden, M. Health-related quality of life in patients with high-grade gliomas: A quantitative longitudinal study. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2015, 124, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijzerman-Korevaar, M.; Snijders, T.J.; De Graeff, A.; Teunissen, S.C.C.M.; De Vos, F.Y.F. Prevalence of symptoms in glioma patients throughout the disease trajectory: A systematic review. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 140, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thier, K.; Calabek, B.; Tinchon, A.; Grisold, W.; Oberndorfer, S. The Last 10 Days of Patients With Glioblastoma: Assessment of Clinical Signs and Symptoms as well as Treatment. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2016, 33, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizoo, E.M.; Braam, L.; Postma, T.J.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Heimans, J.J.; Klein, M.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Taphoorn, M.J.B. Symptoms and problems in the end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients. Neuro-Oncology 2010, 12, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, A.G.; Carson, A.; Grant, R. Depression in Cerebral Glioma Patients: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 103, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterckx, W.; Coolbrandt, A.; De Casterlé, B.D.; Heede, K.V.D.; Decruyenaere, M.; Borgenon, S.; Mees, A.; Clement, P. The impact of a high-grade glioma on everyday life: A systematic review from the patient’s and caregiver’s perspective. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 17, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edelstein, K.; Coate, L.; Massey, C.; Jewitt, N.C.; Mason, W.P.; Devins, G.M. Illness intrusiveness and subjective well-being in patients with glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2016, 126, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, N.; Altshuler, D.B.; Brezzell, A.; Briceño, E.M.; Boileau, N.R.; Miklja, Z.; Kluin, K.; Ferguson, T.; McMurray, K.; Wang, L.; et al. Health Related Quality of Life in Adult Low and High-Grade Glioma Patients Using the National Institutes of Health Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) and Neuro-QOL Assessments. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaichana, K.L.; Halthore, A.N.; Parker, S.L.; Olivi, A.; Weingart, J.D.; Brem, H.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A. Factors involved in maintaining prolonged functional independence following supratentorial glioblastoma resection. J. Neurosurg. 2011, 114, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oberndorfer, S.; Lindeck-Pozza, E.; Lahrmann, H.; Struhal, W.; Hitzenberger, P.; Grisold, W. The End-of-Life Hospital Setting in Patients with Glioblastoma. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, E.L.; Panageas, K.S.; Dallara, A.; Pollock, A.; Applebaum, A.J.; Carver, A.C.; Pentsova, E.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Prigerson, H.G. Frequency and Predictors of Acute Hospitalization Before Death in Patients With Glioblastoma. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halkett, G.; Lobb, E.A.; Rogers, M.M.; Shaw, T.; Long, A.P.; Wheeler, H.R.; Nowak, A.K. Predictors of distress and poorer quality of life in High Grade Glioma patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergo, E.; Lombardi, G.; Guglieri, I.; Capovilla, E.; Pambuku, A.; Zagonel, V.; Zagone, V. Neurocognitive functions and health-related quality of life in glioblastoma patients: A concise review of the literature. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 28, e12410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizoo, E.M.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Buttolo, J.; Heimans, J.J.; Klein, M.; Deliens, L.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Taphoorn, M.J.B. Decision-making in the end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacher, M.; Meixensberger, J.; Krupp, W. Interaction of quality of life, mood and depression of patients and their informal caregivers after surgical treatment of high-grade glioma: A prospective study. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 140, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, A.J.; Kryza-Lacombe, M.; Buthorn, J.; DeRosa, A.; Corner, G.; Diamond, E.L. Existential distress among caregivers of patients with brain tumors: A review of the literature. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2015, 3, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumstarck, K.; Chinot, O.L.; Tabouret, E.; Farina, P.; Barrié, M.; Campello, C.; Petrirena, G.; Hamidou, Z.; Auquier, P. Coping strategies and quality of life: A longitudinal study of high-grade glioma patient-caregiver dyads. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McConigley, R.; Halkett, G.; Lobb, E.; Nowak, A. Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: A time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, B.; Collins, A.; Dally, M.; Dowling, A.J.; Gold, M.; Murphy, M.; Philip, J.A. Living longer with adult high-grade glioma:setting a research agenda for patients and their caregivers. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 120, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubart, J.R.; Kinzie, M.B.; Farace, E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: Family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro-Oncology 2008, 10, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halkett, G.; Lobb, E.A.; Shaw, T.; Sinclair, M.M.; Miller, L.; Hovey, E.; Nowak, A.K. Distress and psychological morbidity do not reduce over time in carers of patients with high-grade glioma. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 25, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, B.; Collins, A.; Dowling, A.J.; Dally, M.; Gold, M.; Murphy, M.; Burchell, J.; Philip, J.A. Predicting distress among people who care for patients living longer with high-grade malignant glioma. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 24, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkett, G.; Lobb, E.A.; Shaw, T.; Sinclair, M.M.; Miller, L.; Hovey, E.; Nowak, A.K. Do carer’s levels of unmet needs change over time when caring for patients diagnosed with high-grade glioma and how are these needs correlated with distress? Support. Care Cancer 2017, 26, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piil, K.; Jarden, M. Bereaved Caregivers to Patients With High-Grade Glioma. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2018, 50, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boele, F.W.; Hoeben, W.; Hilverda, K.; Lenting, J.; Calis, A.-L.; Sizoo, E.M.; Collette, E.H.; Heimans, J.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Reijneveld, J.C.; et al. Enhancing quality of life and mastery of informal caregivers of high-grade glioma patients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 111, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Amatya, B.; Voutier, C.; Khan, F. Advance Care Planning in Patients with Primary Malignant Brain Tumors: A Systematic Review. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gofton, T.E.; Graber, J.; Carver, A. Identifying the palliative care needs of patients living with cerebral tumors and metastases: A retrospective analysis. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2012, 108, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Podgurski, L.M.; Eichler, A.F.; Plotkin, S.R.; Temel, J.S.; Mitchell, S.L.; Chang, Y.; Barry, M.J.; Volandes, A.E. Use of Video to Facilitate End-of-Life Discussions With Patients With Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pace, A.; Villani, V.; Di Pasquale, A.; Benincasa, D.; Guariglia, L.; Ieraci, S.; Focarelli, S.; Carapella, C.M.; Pompili, A. Home care for brain tumor patients. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2014, 1, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hemminger, L.E.; Pittman, C.A.; Korones, D.N.; Serventi, J.N.; Ladwig, S.; Holloway, R.G.; Mohile, N. Palliative and end-of-life care in glioblastoma: Defining and measuring opportunities to improve care. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2016, 4, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Llewellyn, H.; Neerkin, J.; Thorne, L.; Wilson, E.; Jones, L.; Sampson, E.L.; Townsley, E.; Low, J.T.S. Social and structural conditions for the avoidance of advance care planning in neuro-oncology: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Philip, J.A.; Collins, A.; Brand, C.A.; Gold, M.; Moore, G.; Sundararajan, V.; Murphy, M.A.; Lethborg, C. Health care professionals’ perspectives of living and dying with primary malignant glioma: Implications for a unique cancer trajectory. Palliat. Support. Care 2013, 13, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, E.L.; Prigerson, H.G.; Correa, D.C.; Reiner, A.; Panageas, K.; Kryza-Lacombe, M.; Buthorn, J.; Neil, E.C.; Miller, A.M.; DeAngelis, L.M.; et al. Prognostic awareness, prognostic communication, and cognitive function in patients with malignant glioma. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lobb, E.A.; Halkett, G.K.B.; Nowak, A.K. Patient and caregiver perceptions of communication of prognosis in high grade glioma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2010, 104, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, J.A.; Collins, A.; Staker, J.; Murphy, M. I-CoPE: A pilot study of structured supportive care delivery to people with newly diagnosed high-grade glioma and their carers. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2018, 6, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizoo, E.M.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Dirven, L.; Marosi, C.; Grisold, W.; Stockhammer, G.; Egeter, J.; Grant, R.; Chang, S.M.; Heimans, J.J.; et al. The end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 22, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koekkoek, J.A.; Chang, S.; Taphoorn, M.J. Palliative care at the end-of-life in glioma patients. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2016, 134, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizoo, E.M.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Uitdehaag, B.; Heimans, J.J.; Deliens, L.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Pasman, H.R.W. The End-of-Life Phase of High-Grade Glioma Patients: Dying With Dignity? Oncologist 2013, 18, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koekkoek, J.A.F.; Dirven, L.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Sizoo, E.M.; Pasman, H.R.W.; Postma, T.J.; Deliens, L.; Grant, R.; McNamara, S.; Grisold, W.; et al. End of life care in high-grade glioma patients in three European countries: A comparative study. J. Neurooncol. 2014, 120, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, V.; Bohensky, M.A.; Moore, G.; Brand, C.A.; Lethborg, C.; Gold, M.; Murphy, M.A.; Collins, A.; Philip, J.A. Mapping the patterns of care, the receipt of palliative care and the site of death for patients with malignant glioma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2013, 116, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alturki, A.; Gagnon, B.; Petrecca, K.; Scott, S.C.; Nadeau, L.; Mayo, N. Patterns of care at end of life for people with primary intracranial tumors: Lessons learned. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 117, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collins, A.; Sundararajan, V.; Brand, C.A.; Moore, G.; Lethborg, C.; Gold, M.; Murphy, M.A.; Bohensky, M.A.; Philip, J.A. Clinical presentation and patterns of care for short-term survivors of malignant glioma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 119, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forst, D.; Adams, E.; Nipp, R.; Martin, A.; El-Jawahri, A.; Aizer, A.; Jordan, J.T. Hospice utilization in patients with malignant gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diamond, E.L.; Russell, D.; Kryza-Lacombe, M.; Bowles, K.H.; Applebaum, A.J.; Dennis, J.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Prigerson, H.G. Rates and risks for late referral to hospice in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro-Oncology 2015, 18, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dover, L.L.; Dulaney, C.R.; Williams, C.P.; Fiveash, J.B.; Jackson, B.E.; Warren, P.P.; Kvale, E.A.; Boggs, D.H.; Rocque, G.B. Hospice care, cancer-directed therapy, and Medicare expenditures among older patients dying with malignant brain tumors. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 20, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pompili, A.; Telera, S.; Villani, V.; Pace, A. Home palliative care and end of life issues in glioblastoma multiforme: Results and comments from a homogeneous cohort of patients. Neurosurg. Focus 2014, 37, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekatz, B.; Lukasczik, M.; Löhr, M.; Ehrmann, K.; Schuler, M.; Keßler, A.F.; Neuderth, S.; Ernestus, R.-I.; Van Oorschot, B. Screening for symptom burden and supportive needs of patients with glioblastoma and brain metastases and their caregivers in relation to their use of specialized palliative care. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2761–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.K.; May, N.; Verga, S.; Fadul, C.E. Palliative care education in U.S. adult neuro-oncology fellowship programs. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 140, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, J.; Collins, A.; Brand, C.A.; Moore, G.; Lethborg, C.; Sundararajan, V.; Murphy, M.A.; Gold, M. “I’m just waiting.”: An exploration of the experience of living and dying with primary malignant glioma. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quill, T.E.; Abernethy, A.P. Generalist plus Specialist Palliative Care—Creating a More Sustainable Model. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1173–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bickel, K.E.; McNiff, K.; Buss, M.K.; Kamal, A.; Lupu, D.; Abernethy, A.P.; Broder, M.S.; Shapiro, C.L.; Acheson, A.K.; Malin, J.; et al. Defining High-Quality Palliative Care in Oncology Practice: An American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Guidance Statement. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, e828–e838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.A.; Carver, A. Essential competencies in palliative medicine for neuro-oncologists. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2015, 2, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharma, A.; Taylor, L. Malignant Brain Tumors. In Neuropalliative Care: A Guide to Improving the Lives of Patients and Families Affected by Neurologic Disease; Creutzfeldt, C., Kluger, B., Holloway, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Communication Skills Pathfinder. 2019. Available online: https://communication-skills-pathfinder.org/ (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th ed.; National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care: Henrico, VA, USA, 2018.

- Kelley, A.S.; Morrison, R.S. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farabelli, J.P.; Kimberly, S.M.; Altilio, T.; Otis-Green, S.; Dale, H.; Dombrowski, D.; Kieffer, J.R.; Leff, V.; Schott, J.L.; Strouth, A.; et al. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Psychosocial and Family Support. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 23, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.-W.; Chow, A.Y.; Chan, C.L. The effects of life review interventions on spiritual well-being, psychological distress, and quality of life in patients with terminal or advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, E.; Rosenthal, M.A.; Eastman, P.; Le, B.H. Inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with glioblastoma in a tertiary hospital. Intern. Med. J. 2013, 43, 942–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Wolfe, E.; Barrera, C.; Williamson, S.; Farfour, H.; Mrugala, M.; Edwin, M.; Sloan, J.; Porter, A. QOLP-07. A pilot study to assess the integration of a unique proqol tool and early palliative care intervention in the care of high grade glioma patients and their caregivers. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21, vi198–vi199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Ramirez, L.; Herndon, J.; Massey, W.; Lipp, E.; Affronti, M.; Kim, J.-Y.; Friedman, H.; Desjardins, A.; Randazzo, D.; et al. QOLP-18. A time-based model of early palliative care intervention in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma, a single institution feasibility study. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21, vi201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbert, T. Integration of palliative care into the neuro-oncology practice: Patterns in the United States. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2014, 1, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hui, D. Palliative Cancer Care in the Outpatient Setting: Which Model Works Best? Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, M.D.; Hasselaar, J.; Garralda, E.; Van Der Eerden, M.; Stevenson, D.; McKendrick, K.; Centeno, C.; Meier, D.E. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat. Med. 2015, 30, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vierhout, M.; Daniels, M.; Mazzotta, P.; Vlahos, J.; Mason, W.; Bernstein, M. The views of patients with brain cancer about palliative care: A qualitative study. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walbert, T.; Glantz, M.; Schultz, L.; Puduvalli, V.K. Impact of provider level, training and gender on the utilization of palliative care and hospice in neuro-oncology: A North-American survey. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2015, 126, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Tucker, R.; Billings, J.A.; Tulsky, J.; Block, S.D.; von Gunten, C.; Goldstein, N.; Weissman, D.; Morrison, L.J.; Lupu, D.; et al. Hospice and Palliative Medicine Core Competencies. 2009. Available online: http://aahpm.org/fellowships/competencies (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Salsberg, E.; Mehfoud, N.; Quigley, L.; Lupu, D. A Profile of Active Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physicians. 2016. Available online: http://aahpm.org/uploads/Profile_of_Active_HPM_Physicians_September_2017.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Heese, O.; Vogeler, E.; Martens, T.; Schnell, O.; Tonn, J.-C.; Simon, M.; Schramm, J.; Krex, D.; Schackert, G.; Reithmeier, T.; et al. End-of-life caregivers’ perception of medical and psychological support during the final weeks of glioma patients: A questionnaire-based survey. Neuro-Oncology 2013, 15, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philip, J.; Collins, A.; Brand, C.; Sundararajan, V.; Lethborg, C.; Gold, M.; Lau, R.; Moore, G.; Murphy, M. A proposed framework of supportive and palliative care for people with high-grade glioma. Neuro-Oncology 2018, 20, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Country | Number of Centers | Study Type | Number of Participants | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical and Emotional Symptoms | |||||

| Ijzerman-Korevaar (2018) [15] | N/A | N/A | Systematic review | 32 studies addressing symptoms, side effects, and adverse events in glioma patients | • Identifies 10 most common symptoms in different phases of glioma trajectory |

| Psychological Distress | |||||

| Rooney (2013) [18] | Scotland | 2 | Prospective cohort | 154 patients with glioma (low or high grade) |

|

| Sterckx (2013) [19] | N/A | N/A | Systematic review | 16 qualitative studies of impact of HGG on everyday life | • Sources of distress include death anxiety, loss of autonomy, and behavior/personality changes |

| Edelstein (2015) [20] | Canada | 1 | Cross-sectional survey focusing on psychiatric components of care | 73 patients with GBM |

|

| Functional Status | |||||

| Gabel (2019) [21] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 58 patients with HGG and 21 with LGG |

|

| Chaichana (2011) [22] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 544 patients with KPS ≥ 80 a who underwent first-time resection of primary or secondary GBM |

|

| Cognitive Dysfunction | |||||

| Bergo (2019) [26] | N/A | N/A | Narrative review | Studies addressing cognition and HRQOL in HGG |

|

| Sizoo (2012) [27] | Netherlands | 3 | Cross-sectional survey | Physicians and relatives of 155 deceased HGG patients |

|

| Health-Related Quality of Life | |||||

| Gabel (2019) [21] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 58 patients with HGG and 21 with LGG | • Majority of patients in both groups prioritized HRQOL over survival |

| Halkett (2015) [25] | Australia | 4 | Prospective cohort | 116 HGG patients |

|

| Author (Year) | Country | Number of Centers | Study Type | Number of Participants | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thier (2016) [16] | Austria | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 57 patients with GBM | • Identifies most common symptoms and medications in last 10 days of life |

| Sizoo (2010) [17] | Netherlands | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 55 patients with HGG | • Depressed mental status, dysphagia were most common symptoms in final week of life |

| Oberndorfer (2008) [23] | Austria | 1 | Retrospective chart review | 29 patients with GBM |

|

| Diamond (2017) [24] | USA | 1 | Retrospective data analysis | 385 GBM patients |

|

| Sizoo (2014) [27] | N/A | N/A | Systematic Review | 17 studies addressing the end-of-life phase for HGG patients |

|

| Koekkoek (2016) [50] | N/A | N/A | Narrative Review | N/A |

|

| Sizoo (2012) [51] | Netherlands | 3 | Cross-sectional survey | 101 providers 50 relatives |

|

| Koekkoek (2014) [52] | Netherlands Austria Scotland | 7 | Cross-sectional survey | 207 caregivers of HGG decedents | • Predictors caregiver satisfaction with end-of-life care include dying in preferred location; symptom control; meeting of informational needs |

| Sundararajan (2014) [53] | Australia | Many | Retrospective cohort | 678 malignant glioma patients |

|

| Alturki (2014) [54] | Canada | Many | Retrospective analysis | 1623 decedents with primary intracranial tumors |

|

| Collins (2014) [55] | Australia | Many | Retrospective cohort | 482 malignant glioma patients who died within 120 days of diagnosis |

|

| Author | Country | Number of Centers | Study Type | Number of Participants | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Palliative Care | |||||

| Sizoo (2012) [27] | Netherlands | 3 | Cross-sectional survey | Physicians and relatives of 155 deceased HGG patients | • 40% of physicians did not discuss end-of-life preferences with patients |

| Gofton (2012) [40] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 168 patients with any CNS tumor (101 with HGG) |

|

| El-Jawahri (2010) [41] | USA | 1 | Randomized controlled trial of a verbal narrative of end-of-life treatment options vs verbal narrative plus a video depicting the treatments | 50 patients with HGG (23 in intervention arm, 27 controls) |

|

| Pace (2014) [42] | Italy | 1 | Pilot intervention of in-home neurology visits, neuro-rehabilitation, psychological support, nursing assistance | 848 patients with any brain tumor |

|

| Hemminger (2017) [43] | USA | 1 | Retrospective cohort | 117 decedents with GBM |

|

| Pompili (2014) [59] | Italy | 1 | Pilot intervention of in-home neurology visits, neuro-rehabilitation, psychological support, nursing assistance | 122 patients with GBM |

|

| Specialty Palliative Care | |||||

| Sundararajan (2014) [53] | Australia | Many | Retrospective cohort | 678 malignant glioma patients |

|

| Collins (2014) [55] | Australia | 4 | Retrospective cohort | 1160 decedents with PMBT |

|

| Seekatz (2017) [60] | Germany | 1 | Serial cross-sectional survey | 54 patients with GBM |

|

| Hospice | |||||

| Forst (2017) [56] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 12437 decedents with malignant glioma |

|

| Diamond (2016) [57] | USA | 1 | Retrospective cohort | 160 decedents with PMBT who enrolled in hospice prior to death |

|

| Dover (2018) [58] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 1323 deceased Medicare beneficiaries with a malignant brain tumor (383 with PMBT, 940 with SMBT) |

|

| Author | Country | Number of Centers | Study Type | #Of Participants | Gaps Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pace (2017) [13] | N/A | N/A | Systematic Review and Expert Opinion | 223 articles on palliative care needs and management of glioma |

|

| Halkett (2018) [36] | Australia | 4 | Prospective cohort | 118 caregivers of HGG patients |

|

| Sizoo (2012) [27] | Netherlands | 3 | Cross-sectional survey | 101 providers 50 relatives of decedents with HGG | • Physicians are often unaware of patients’ end-of-life preferences |

| Gofton (2012)40 | USA | 1 | Retrospective data analysis | 101 deceased HGG patients |

|

| Hemminger (2017) [43] | USA | 1 | Retrospective cohort | 117 decedents with GBM | • Patients received late ACP documentation and minimal early palliative care |

| Diamond (2017) [46] | USA | 1 | Mixed methods (prognostic awareness assessment tool and semi-structured interviews) | 50 patients with HGG with 32 matched caregivers |

|

| Sizoo (2014) [49] | N/A | N/A | Systematic Review | 17 studies addressing the end-of-life phase for HGG patients | • Limited research and no adequate guidelines on end of life care for HGG patients, including symptom management, ACP, and organization of care |

| Collins (2014) [55] | Australia | 4 | Retrospective cohort | 1160 decedents with PMBT | • Under-utilization of palliative care in patients who survived a first hospital admission but died within 120 days |

| Forst (2017) [56] | USA | 1 | Retrospective analysis | 12,437 decedents with malignant glioma | • Patients often referred late (<7 days before death) to hospice |

| Mehta (2018) [61] | USA | 17 | Cross-sectional survey | 17 neuro-oncology fellowship program directors | • No consistent palliative care education for neuro-oncology fellows |

| Philip (2014) [62] | Australia | 2 | Qualitative interviews | 10 patients with HGG | • Patients perceived providers as focused on “here and now,” lacking openness about the future, reluctant to discuss palliative care |

| Author | Country | Number of Centers | Study Type | #Of Participants | Key Figurendings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||||

| Seekatz (2017) [60] | Germany | 1 | Serial cross-sectional survey | 54 patients with GBM |

|

| Vierhout (2017) [78] | Canada | 1 | Qualitative interviews | 39 patients with malignant brain tumor | Patients want palliative care at home; open to palliative care if it does not decrease optimism; prefer to receive palliative care early |

| Philip (2014) [62] | Australia | 2 | Qualitative interviews | 10 patients with HGG |

|

| Neuro-oncologists | |||||

| Llewellyn (2017) [44] | UK | 1 | Qualitative interviews | 15 interdisciplinary health care providers |

|

| Philip (2015) [45] | Australia | 3 | Qualitative interviews | 35 interdisciplinary health care providers |

|

| Walbert (2016) [79] | USA | Many | Cross-sectional survey | 239 interdisciplinary neuro-oncology providers |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crooms, R.C.; Goldstein, N.E.; Diamond, E.L.; Vickrey, B.G. Palliative Care in High-Grade Glioma: A Review. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100723

Crooms RC, Goldstein NE, Diamond EL, Vickrey BG. Palliative Care in High-Grade Glioma: A Review. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(10):723. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100723

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrooms, Rita C., Nathan E. Goldstein, Eli L. Diamond, and Barbara G. Vickrey. 2020. "Palliative Care in High-Grade Glioma: A Review" Brain Sciences 10, no. 10: 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100723

APA StyleCrooms, R. C., Goldstein, N. E., Diamond, E. L., & Vickrey, B. G. (2020). Palliative Care in High-Grade Glioma: A Review. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100723