Efficacy of the Treatment of Developmental Language Disorder: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Developmental Language Disorder

Interventions for the Developmental Language Disorder

2. Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

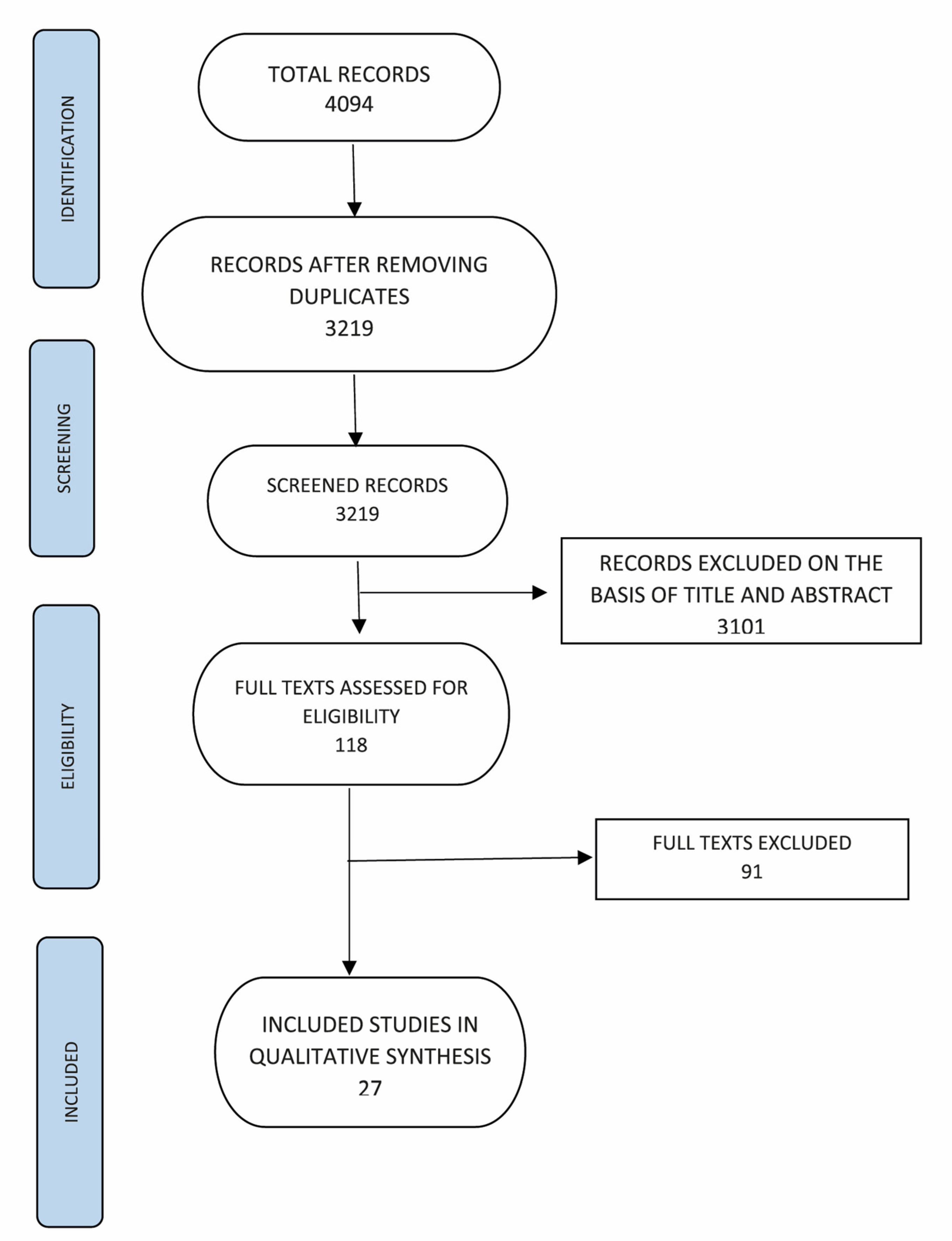

2.2. Source of Data and Screening

2.3. Data Selection, Extraction and Quality Assessment

- from 8 to 12 criteria with the a “yes” assessment: high quality;

- from 4 to 7 criteria with the “yes” assessment: medium quality; and,

- 3 or less criteria with the “yes” assessment: low quality.

- -

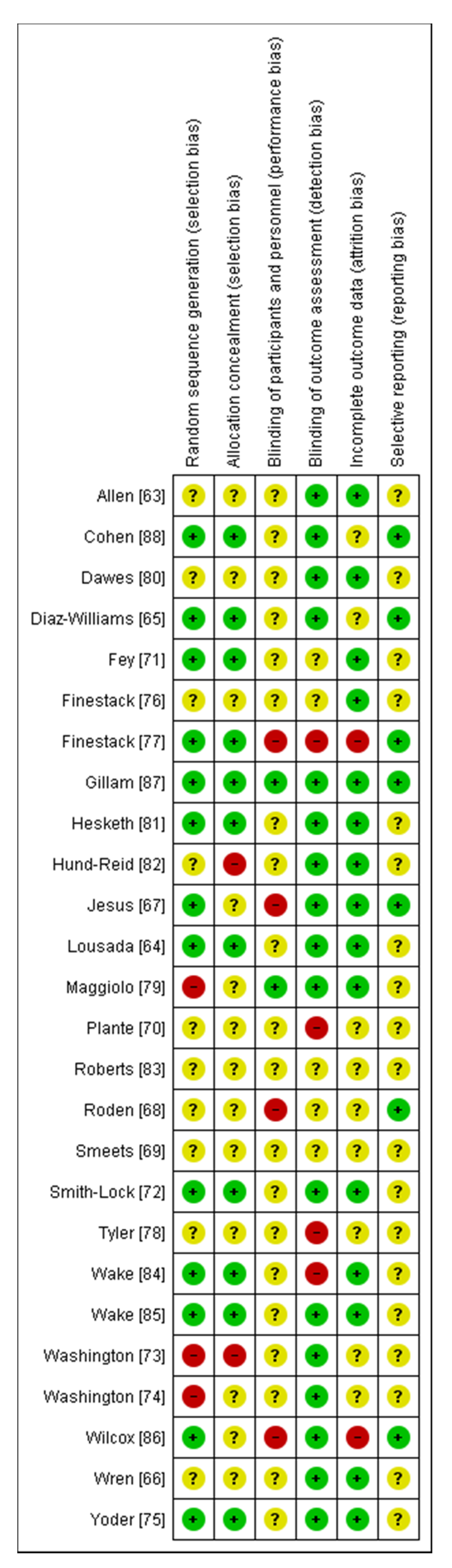

- random sequence generation (selection bias), which considers the risk that the allocation of subjects in the experimental and control groups may have occurred in a non-random way, indicating a possible problem in the selection of groups;

- -

- allocation concealment (selection bias), which evaluates the degree of protection against the risk that the trial operators are aware of the mechanism of random allocation of subjects;

- -

- the blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), which considers the risk that the lack of blindness of trial objectives in participants and staff might alter performance (e.g., favoring a lack of expectations for the control group), thus affecting the trial outcome;

- -

- blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), which indicates the risk that persons evaluating the study’s outcome are aware of the group assignment to different forms of intervention, thus influencing the probability of capturing the effects of the intervention;

- -

- incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), which evaluates the possibility that the presence of missing data modifies the estimation of the effects of interventions. The reasons for attrition or exclusion were reported as well as whether missing data were balanced across groups or related to outcomes; and,

- -

- selective reporting (reporting bias), which indicates the possible risk that only a selection of variables is presented in the report, e.g., the tendency not presenting measures for which the results were not significant (e.g., not presenting measures for insignificant results).

2.4. Data Synthesis

Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies

- interventions compared to no treatment or later treatments;

- specific interventions with respect to general stimulation conditions (e.g., studies in which children in the control group were assigned to conditions that were designed to simulate interaction in therapy without promoting the language area of interest. These are cognitive therapy, general play sessions or speech therapy that did not focus on the area of the specific linguistic deficit considered); and,

- interventions compared to other language therapy approaches (e.g., studies comparing what they considered a “traditional treatment” with what they considered to be an experimental treatment. The latter could be a different approach performed by the same person, such as “targeting early” against “late developing sounds”, or the same approach performed by different people, as in the case of “focused stimulation” provided by clinicians against that implemented by parents).

3.1.1. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

3.1.2. External Validity

3.2. Effect of Intervention

3.2.1. Expressive Phonological Skills

3.2.2. Receptive Phonological Skills

3.2.3. Expressive Vocabulary

3.2.4. Receptive Vocabulary

3.2.5. Morphological and Syntactic Expressive Skills

3.2.6. Morphological and Syntactic Receptive Skills

3.2.7. Narrative Skills

3.2.8. Meta-Phonological Skills

3.2.9. General Language Skills

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Clinical Practice and Research

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy for PubMed

| #18 | #15 OR #17 |

| #17 | #13 AND #16 |

| #16 | randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OT randomized [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR clinical trials as topic [mesh: noexp] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [ti] OR groups [tiab] |

| #15 | #13 AND #14 |

| #14 | systematic[sb] OR meta-analysis[pt] OR meta-analysis as topic[mh] OR meta-analysis[mh] OR meta analy*[tw] OR metanaly*[tw] OR metaanaly*[tw] OR met analy*[tw] OR integrative research[tiab] OR integrative review*[tiab] OR integrative overview*[tiab] OR research integration*[tiab] OR research overview*[tiab] OR collaborative review*[tiab] OR collaborative overview*[tiab] OR systematic review*[tiab] OR technology assessment*[tiab] OR technology overview*[tiab] OR “Technology Assessment, Biomedical”[mh] OR HTA[tiab] OR HTAs[tiab] OR comparative efficacy[tiab] OR comparative effectiveness[tiab] OR outcomes research[tiab] OR indirect comparison*[tiab] OR ((indirect treatment[tiab] OR mixed-treatment[tiab]) AND comparison*[tiab]) OR Embase*[tiab] OR Cinahl*[tiab] OR systematic overview*[tiab] OR methodological overview*[tiab] OR methodologic overview*[tiab] OR methodological review*[tiab] OR methodologic review*[tiab] OR quantitative review*[tiab] OR quantitative overview*[tiab] OR quantitative synthes*[tiab] OR pooled analy*[tiab] OR Cochrane[tiab] OR Medline[tiab] OR Pubmed[tiab] OR Medlars[tiab] OR handsearch*[tiab] OR hand search*[tiab] OR meta-regression*[tiab] OR metaregression*[tiab] OR data synthes*[tiab] OR data extraction[tiab] OR data abstraction*[tiab] OR mantel haenszel[tiab] OR peto[tiab] OR der-simonian[tiab] OR dersimonian[tiab] OR fixed effect*[tiab] OR “Cochrane Database Syst Rev”[Journal:__jrid21711] OR “health technology assessment winchester, england”[Journal] OR “Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep)”[Journal] OR “Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ)”[Journal] OR “Int J Technol Assess Health Care”[Journal] OR “GMS Health Technol Assess”[Journal] OR “Health Technol Assess (Rockv)”[Journal] OR “Health Technol Assess Rep”[Journal] |

| #13 | #1 AND #10 AND #11 AND #12 |

| #12 | Child[Mesh] OR Infant[Mesh] OR child*[tiab] OR infant*[tiab] OR baby[tiab] OR babies[tiab] OR toddler*[tiab] OR boy*[tiab] OR girl*[tiab] OR pre-school*[tiab] OR preschool*[tiab] OR kindergarten*[tiab] OR kinder-garten[tiab] OR nursery[tiab] |

| #11 | test*[tiab] OR instrument[tiab] OR judgments[tiab] OR scale[tiab] OR tool*[tiab] OR procedure*[tiab] OR assessment [tiab] OR assessing[tiab] OR vignette*[tiab] OR scenario*[tiab] OR “rating scale”[tiab] OR “rating scales”[tiab] OR “coding manuals”[tiab] OR “coding schemes”[tiab] OR checklist*[tiab] OR interview*[tiab] OR questionnaire*[tiab] |

| #10 | #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 |

| #9 | reliability[tiab] |

| #8 | early identification [tiab] |

| #7 | accuracy[tiab] |

| #6 | “Sensitivity and Specificity” [Mesh] |

| #5 | “Predictive Value of Tests” [Mesh] |

| #4 | “reproducibility of Results” [MESH] |

| #3 | Diagnosis” [Mesh] OR “diagnosis” [Subheading] |

| #2 | diagnosis” [tiab] OR “diagnostic” [tiab] |

| #1 | “Language Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Speech Sound Disorder”[Mesh] OR speech disorder*[tiab] OR speech delay*[tiab] OR speech impair*[tiab] OR language disorder*[tiab] OR language delay*[tiab] OR language impair*[tiab] OR language difficulties[tiab] OR phonological disorder* [tiab] |

Appendix B. Characteristics of the RCT Studies Included in the Systematic Review

| Authors, Year, Country, Reference | Language | Setting, Provider | Sample Characteristics | Interventions | Length of Intervention | Outcomes |

| Allen, 2013, USA [63] | English/American | Setting: developmental preschool, “Head Start”, preschool, “Childcare, home Provider: Speech therapists and researcher-trained assistants | Population N = 54 with SSD (M = 39, F = 15); Age range = 3–5.5 years; Mean age = 4.4 years | Three arms: P1 = one-time-per-week phonological intervention P3 = three-times-per-week phonological intervention; C = active control | Intervention: P1 24 weeks P3 8 weeks C 8 weeks Follow-up: P1 and P3 were re-examined after a six-weeks maintenance period | Phonological skills (PCC primary measure) |

| Lousada et al., 2013, Portugal [64] | Portuguese | Setting: University of Aveiro Provider: Speech therapist | Population N = 14 with phonologically based SSD; M = 10, F = 4; Age range = 4–6.7 years; Mean age = 5.2 years | Two arms:

| Intervention: 25 (45 min) individual sessions (one per week) with the same therapist (blind to the objectives of the study) | Phonological skills (PCC primary measure) |

| Diaz-Williams, 2013, USA [65] | English/American | Setting: structured environment in school Provider: School intervention: speech therapist Home intervention: parents | Population N = 30 speech impaired (in expressive but not receptive language skills) based on the school district identification process; M = 26, F = 4; age range = 3.6–5.3 years; Mean age = 4.5 years | School-based traditional phonological intervention associated with three different types of homework intervention procedures:

| Intervention: 12 weeks School intervention: 1hr twice a week Home intervention: five times a week (60 sessions) | Phonological competence measured with the HAPP-3 test [90] |

| Wren and Roulstone, 2008, UK [66] | English | Setting: school Provider: speech therapist | Population A total of 33 children participated to the study (N = 33; M = 25, F = 8; Age range = 4.2–7.8 years; Mean age = 5.6 years). | Three arms:

| Intervention: One 30 min session per week for eight weeks Follow-up: three weeks after the end of training | Phonological competence measured with GFTA Sounds in Words subtest [91]; PCC |

| Jesus et al. 2019, Portugal [67] | Portoguese | Setting: School Provider: speech-language pathologist | Population = 22 with SSD (M = 18, F = 4); Mean age = 57 months | Two arms Table top group: Phonologically based intervention: combination of phonological awareness activities, phonological awareness program, auditory bombardment, and discrimination and listening tasks. Tabletop materials consisted of printed cards, board games, stuffed animals, cardboard boxes, a large dice, fishing rods, and other similar materials used in traditional therapy. Tablet group: Phonologically based intervention (as above). The method of presenting the materials is by tablet. All the activities were run on an 8-in screen ASUS MeMO Pad 8 | Intervention: 3 months. 12 weekly 45 min. individual sessions. Intervention was divided into two 6-session blocks: T0 = baseline T1 = first assessment at baseline T2 = 3-month waiting period T3 = post intervention | Phonological skills measured by University of Aveiro’s Case History Form for Child Language [101], the TFF-ALPE phonetic–phonological test [102], the TL-ALPE language test [103], and the PAOF oromotor abilities test [104]. PCC, percentage of vowels correct, and percentage of phonemes correct |

| Roden et al. 2019, Germany [68] | German | Setting: School Provider: Preschool teachers | Population: ASTM group: N = 40 (M = 24, F = 16); mean age = 4.52 years; PA group: N = 24, (M = 16, F = 8); mean age = 4.54 years; Control group: N = 37 (M = 22, F = 15); mean age = 4.51 years | Experimental group: “Auditory Stimulation Training with Technically Manipulated Musical Material”: listening, over earphones, to music acoustically modified, particularly (1) only high frequency, (2) electronic filters removing low frequency (<1000 Hz) and boosted medium and high frequency (>2000 Hz), (3) medium and high frequency were lateralized. Pedagogical activity program: preparation of primary school skills Control group: no treatment | Intervention: 3 30-min weekly session for 12 weeks | Digit span, non-word recall and recall of sentence (HASE) [105], Phoneme discrimination test with and without background noise, speech perception at high frequency |

| Smeets et al., 2012, Netherlands [69] | Dutch | Setting: structured environment in kindergarden (both) | Population Exp. 1: N = 29 children with DLD; M = 24, F = 5; Age range = 60–80 months; Exp. 2: N = 23) children with DLD (who did not participate in exp. 1); M = 13, F = 12; Age range = 60–90 months) | Exp. 1: Three conditions (randomized within subjects): 1. Two electronic storybooks in a static format; 2. Two electronic storybooks in a video format; 3. Control: no presentation Exp. 2: Four conditions (randomized within subjects): static books without background music or sounds (1) or with background music or sounds (2), video books without background music or sounds (3), or with background music or sounds (4). | Intervention Exp. 1: Eight sessions (two per week) —four weeks Exp. 2: Two periods of four weeks with eight sessions each (two per week) were used to counterbalance presentation of intervention materials | Exp. 1: Target vocabulary test designed for the study, and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test Exp. 2: Target vocabulary test (as in Exp 1), Phonological NWR Working Memory, Digit span, CELF-4-NL [106] |

| Plante et al., 2014, USA [70] | English/American | Setting: University clinic Provider: trained clinicians | Population Experimental group: N = 9; M = 6, F = 3; Age range = 4.3–5.7 years; Mean age = 5.2 years; Control group: N = 9 children (M = 5, F = 4; Age range = 4.0–5.9 years; Mean age = 4.9 years) | Two arms:

| 25 min. individual daily sessions for six weeks (for a maximum of 25 sessions) | Percentage-of-correct-use data from materials and verbs not used during treatment; number of correct spontaneous uses of treated and control morphemes |

| Fey et al., 2016, USA [71] | English/American | Setting: University Provider: Study staff | Population: N = 20 with DLD; M = 14, F = 6 monolingual; Mean age = 3.8 years; Experimental group: N = 9, M = 6, F = 3; Mean age = 3.8 years; Control group: N = 11 children; M = 8, F = 3; Mean age = 3.7 years | Group 1: Competing sources of input;Three treatment sections for each target morpheme (the auxiliary “is” and the suffix of the third person singular/3S); past tense “-ed” was monitored as a control:

| Intervention: 12 weeks Frequency: 2 sessions per week (30–40′) | Morphological and syntactic expressive skills |

| Smith-Lock et al., 2015, Australia [72] | English/Australian | Setting: schools for children with language difficulties Provider: Speech-language pathologist, classroom teachers, and education assistants | Population Children with a DLD—diagnosis made by a speech-language pathologist; Experimental group: N = 17; M = 13, F = 4; Mean age = 5.1 years), Control group: N = 14; M = 12, F = 2; Mean age = 5.1 years) | Two conditions:

| Intervention: weekly 1-hr sessions for 8 weeks; both whole-class (approximately 12 children) and small-group activities Follow up: 8 weeks after the end of therapy | Grammatical tests (Grammar Screening Test, the Articulation Screening Test, and the Gram- mar Elicitation Test) [93] |

| Washington et al., 2011, Canada [73] | English | Setting: Not specified Provider: speech therapist | Population Group 1 (C-AT): N = 11; M = 8, F = 3; Mean age = 4.4 years) Group 2 (nC-AT): N = 11; M = 8, F = 3; Mean age = 4.5 years; control group (NT): N = 12; M = 11, F = 1; Mean age = 4.1 years | Experimental Group 1 (C-AI): Computer-Assisted program, “My Sentence Builder”, includes social content embedded in a series of activities useful for sentence production. Experimental Group 2 (nC-AT): Table-top procedures for sentence elicitation with predominant use of verbal instructions; use of objects/toys Control group: no treatment | Intervention: 10 individual weekly sessions of 20′ Follow up: Three months after the end of therapy | Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test-Preschool (SPELT-P; [94]; Developmental Sentence Scoring (DSS; [95]) |

| Washington et al., 2013, Canada [74] | English | Setting: Not specified Provider: speech therapist | Population Groups 1 and 2 as in [73] | Same as Groups 1 and 2 as in [73] | Same as in [73] | session-to-session progress in terms of efficiency and syntactic growth |

| Yoder et al., 2011, USA [75] | English/American | Setting: university clinic Provider: speech therapists trained in the treatments | BTR group: N = 34; Mean age = 3.6 years; MLT group: N = 28; Mean age = 3.6 years | Milieu language teaching (MLT; [107]) focuses on child-lefted play to elicit the child’s use of utterances containing preselected grammatical targets. Broad Target Recasts (BTR [108]) is an intervention which follows child’s play with the aim of grammatically recasting the child’s utterances | Individual 30-min sessions three times a week for a period of 6 months. | Progressive grammar as assessed by the Index of Productive Syntax (IPSyn) from 2 conversational language samples |

| Finestack and Fey, 2009, USA [76] | English/American | Setting: at home or at school Provider: Not specified | Deductive group: N = 16; M = 9, F = 7; Mean age = 7.3 years; Inductive group: N = 16; M = 10, F = 6; Mean age = 7.4 years | Explicit instruction: Sessions 1 and 2: the researcher teaches a new grammatical morpheme (-pa or -po that do not exist in English associated with masculine or feminine) with the modeling technique associated with an explicit auditory prompt; Sessions 3 and 4: the researcher requires the production of the new grammatical morpheme with pictures and explicit auditory prompt Implicit instructions: Same intervention as above but auditory prompt in task with modeling and with recast is implicit | Four individual teaching sessions within a 2-week period | Learning the new grammar rule measured as the percentage of correct answers and classifying children into: pattern, undifferentiated, and bare stem users |

| Finestack, 2018, USA [77] | English/American | Setting: at home or at school Provider: Not specified | 25 children Explicit-implicit group (E-I): N = 12; M = 10, F = 2; Mean age = 6.77 years; Implicit-only group (I-O): N = 7; M = 6, F = 6; Mean age = 7.35 years | Training of three novel grammatical forms (gender, aspect and first person). Each session included a learning check, followed by a teaching task and an acquisition probe (presented via computer to ensure consistency of delivery). For the E-I group the computer presented participants the rule guiding use of the novel target form. The I-O group received a filler instruction. Prompts (and feedback) was provided in the second part of the teaching session An acquisition probe (with no feedback) was given at the end of each teaching session | Five computer-based teaching 20 min. sessions for each of the three novel grammatical targets. 1 week of waiting period after completion of each target | Learning of the novel grammatical rule. Children were classified as pattern user (PU: at least 80% performance) or non-pattern user (non-PU) for each of the three grammatical targets separately for the acquisition, maintenance and generalization probe |

| Tyler et al., 2002, USA [78] | English/American | Setting: school context Provider: speech therapy student under the supervision of a speech therapist | - Group with morpho-syntactic intervention first: N = 10; Mean age = 4.3 years - Group with phonological intervention first: N = 10; Mean age = 4.1 years - Control group with no treatment: N = 7 | Combined morpho-syntactic and phonological interventions carried out in sequence

| Intervention: individual session of 30 min and group session of 45 min–2 times a week Follow-up: 12 weeks and 24 weeks; for the control group: 12–15 weeks post-treatment | Morpho-syntactic test based on free speech Phonological evidence measured with the standardized test BBTOP |

| Maggiolo et al., 2003 Chile [79] | Spanish | Setting: schools Provider: teachers | Population 14 children (M = 4, F = 10; Mean age = 4.6 years) Intervention group: N = 7 Control group: N = 7 | Intervention group: interaction activities with the child; development of the experimental program (structured into five mini-programs: temporal relationships; causal and purpose relationships; story presentation; storytelling; and storytelling structure); and interactive storytelling. Control group: no treatment. | Intervention: Sixteen session (2 sessions per week-45′) | Narrative skills (clinical test of the authors) |

| Dawes et al., 2019 Australia [80] | English | Setting: school Provider: Researcher | Experimental group (ICI): N = 19 Control group (PA) N = 18 Total: N = 37 (27 males) Mean Age 5.5 | Experimental group (ICI): Inferential comprehension intervention (ICI) focused on book sharing, shared creation of a story map, retelling part of the story using the story map, discussion about character emotions and linking emotions to personal experiences, prediction (after the end of the story) Control group (PA): Gillon Phonological Awareness Training Program [109] | Intervention: 16 sessions (2 sessions a week over 8 weeks) Follow up: 8–9 weeks post-intervention | Inferential comprehension of narratives: questions requiring causal reasoning (including inferring emotions), prediction, and evaluative reasoning. Squiller Story Narrative Comprehension Assessment and Peter and the Cat Narrative Comprehension Assessment (NCA [110,111] |

| Hesketh et al., 2007 UK, [81] | English | Setting: home or school context (depending on parents’ preference) Provider: Speech therapists | Population Intervention group: 22 children (M = 17, F = 5; Mean age = 4.2 years). Control group (N = 20; M = 17, F = 3; Mean age = 4.3 years) | Intervention group: specific training on meta-phonological skills. The tasks focused first on syllables and rhymes, then on the recognition of the first and last phoneme of the word, and, finally, on the phonological manipulation of adding or deleting phonemes in the word. Control group: language stimulation (LS) program with activities of linguistic comprehension, knowledge of writing, verbalization of emotions and development of vocabulary and semantics. | Intervention: 20 individual sessions (20′-30′), two or three session per week | Meta-phonological skills (Syllable and phoneme) Phoneme Addition and Deletion task Primary and Pre-school Inventory of Phonological Awareness (PIPA) [112] Metaphon Screening Assessment [113] |

| Hund-Reid and Schneider, 2013, Canada, [82] | English | Setting: home or school context (depending on parents’ preference) Provider: Speech therapists | Population Experimental group: N = 22; M = 17, F = 5; Mean age = 5.6 years Control group: N = 15; M = 10, F = 5; Mean age = 5.3 years | Experimental group: the phonological awareness program: “Road to the Code” [85], based on principles that include, in each session, explicit teaching of one or two types of phoneme manipulations (e.g., initial sound isolation and/or initial sound identification) and fusion and segmentation, as well as sound-symbol awareness activities (manipulation of phonemes with letters). Control group: no treatment | Intervention: In groups of two, 20-minutes sessions with penta-weekly frequency, for 14 weeks | Phonological awareness (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Skills, DIBELS) [114] |

| Roberts et al. 2012, USA, [83] | English | Setting: Clinic and home Provider: Parents (specifically trained by therapists and educators) | Experimental group: N = 16; M = 14, F = 2; Mean age = 2.6 years Control group of children with DLD: N = 18; M = 13, F = 5; Mean age = 2.6 years Control group of children with typical language development: N = 28; M = 26, F = 2; Mean age = 2.5 years | Experimental group: “Enhanced Milieu Teaching” (EMT) in 4 phases: setting the basics for communication; shaping and broadening communication; time delay strategies; and, finally, prompt strategies. Control groups: no treatment | Intervention: Bi-weekly 1-hr sessions (one in the clinic and one at home) for a total of 24 sessions over 3 months. | Receptive and expressive skills (Preschool Language Scale-fourth edition, PLS-4) [115] |

| Wake et al. 2013, 2015 Australia, [84,85] | English | Setting: Home Provider: Parents | Experimental group (N = 99, 24% F, Mean age = 4.2 years) Control group: N = 101, 36% F, mean age = 4.1 years | Experimental group: “Let’s Read” and “Let’s Learn Language” programs promoting narrative skills, vocabulary, grammar, phonological awareness and pre-reading skills; each session consists on: a) a short review of the previous week; b) activities introduced by the researcher directed to the child; c) activities for parents and children to be carried out together with the support of the researcher; and d) activities for home practice Control group: no treatment | Intervention: 18 sessions distributed in 3 blocks of 6 weeks Follow up: Wake [76] at 6 years | Receptive and expressive language (CELF-P2 [88]), phonological processing (Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing), Letter knowledge task |

| Wilcox et al. 2019, USA, [86] | English/American | Setting: School Provider: Preschool teachers | Population: 289 children (202 M, 87 F, mean age 53.09 months) TELL curriculum N = 142 BAU N = 147 | Experimental group: TELL (Teaching Early Literacy and Language): a whole-class curriculum that embeds incidental and explicit oral language and early teaching practices within typical preschool activities; it includes materials and structured activities in two weeks’ 14 thematic units. Control group: Business as Usual (BAU) | Intervention: 34 weeks of instruction during a school year | Receptive and expressive language (CELF-P2 [116]), vocabulary and phonological processing (TOPEL [117]), phonological awareness and letter knowledge (PALS-PreK [118]), receptive and expressive vocabulary (TELL vocabulary) |

| Gillam et al. 2008 [87] | English/American | Setting: school Provider: Speech-language pathologist | Population: 216 with language impairment (136 M, 80 F); mean age 7 years 6 months FFW-L N = 54 CALI N = 54 ILI N = 54 AE N = 54 | Four arms Fast For Word-Language (FFW-L): children played computer games that targeted discrimination of tones, detection of individual phoneme changes, matching phonemes to a target, identifying matched syllable pairs, discriminating between minimal pair words, recalling commands, comprehending grammatical morphemes and complex sentence structures; speech and nonspeech stimuli were acoustically modified. Computer assisted Language Intervention (CALI): children played the same computer games of FFW-L without any acoustically modification. Individual Language Intervention (ILI): individual activities developed around 13 picture books, designed to target semantics, morphosyntax, narration and phonological awareness. Academic Enrichment (AE): computer games designed to teach mathematics, science and geography. | FFW-L: 1h and 40′ per day, five day per week, for six weeks; five of the seven plays each day CALI: 1h and 40′ per day, five day per week, for six weeks ILI: 1h and 40′ per day, five day per week, for six weeks AE: not specified T0 = before treatment T1 = immediately after treatment (6 weeks after T0) T2 = 3 months after treatment T3 = 6 months after treatment | Primary outcomes: Expressive and receptive language (CASL [119]); backward masking Secondary outcomes: sentence comprehension (Token Test for Children, [120]); phonological awareness (Blending Words subtest od the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing [121]) |

| Cohen et al., 2005, UK, [88] | English | Setting: home Provider: Parental supervision, parents were trained by speech-language pathologist | Population: 77 children (M = 55, F = 22); mean age = 88.92 months Group A: N = 23 Group B: N = 27 Group C: N = 27 | Group A—Fast ForWord Language: children played computer games designed to develop oral language comprehension and listening skills, with acoustically modified speech Group B—Computer software: children played with age appropriate educational software packages designed to encourage aspects of language development Group C—Control: no intervention | Group A: 90 minutes, 5 days a week for 6 weeks Group B: 90 minutes, 5 days a week for 6 weeks T0 = pretreatment T1 = 9-week T2 = 6 months follow up | Receptive and expressive language (CELF-3 [116], TOLD-P:3 [122]) Phonological awareness (PhAB [123]) Narrative production (Bus Story Test, [124])) |

| Legenda: SSD: speech-sound disorder PA: phonological awareness; PCC: percentage of correct consonants. | ||||||

References

- Rapin, I. Language heterogeneity and regression in the autism spectrum disorders—Overlaps with other childhood language regression syndromes. Clin. Neurosci. Res. 2006, 6, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.M.V. Pre- and perinatal hazards and family background in children with specific language impairments: A study of twins. Brain Lang. 1997, 56, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, G.; Bishop, D.V.M. A comparison of language abilities in adolescents with Down Syndrome and children with specific language impairment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2003, 46, 1324–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Boyle, J.; Harris, F.; Harkness, A.; Nye, C. Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: Findings from a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2000, 35, 165–188. [Google Scholar]

- Roch, M.; Florit, E.; Levorato, M.C. La produzione di narrative in bambini con disturbo di linguaggio di età prescolare [Narrative production in preschool children with language impairment]. G. Neuropsichiatr. Dell’Età Evol. 2017, 37, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, I.F.; Berkman, N.D.; Watson, L.R.; Coyne-Beasley, T.; Wood, C.T.; Cullen, K.; Lohr, K.N. Screening for speech and language delay in children 5 years old and younger: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collisson, B.A.; Graham, S.A.; Preston, J.L.; Rose, M.S.; McDonald, S.; Tough, S. Risk and protective factors for late talking: An epidemiologic investigation. J. Ped. 2016, 172, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawa, V.V.; Spanoudis, G. Toddlers with delayed expressive language: An overview of the characteristics, risk factors and language outcomes. Res. Dev. Dis. 2014, 35, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescorla, L. Late talkers: Do good predictors of outcome exist? Dev. Dis. Res. Rev. 2011, 17, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, A.; Jooss, B.; Rupp, A.; Dockter, S.; Blaschtikowitz, H.; Heggen, I.; Pietz, J. Children with developmental language delay at 24 months of age: Results of a diagnostic workup. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2008, 50, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarais, C.; Sylvestre, A.; Meyer, F.; Bairati, I.; Rouleau, N. Systematic review of the literature on characteristics of late-talking toddlers. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2008, 43, 361–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.B. Is expressive language disorder an accurate diagnostic category? Am. J. Lang. Path. 2009, 18, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chilosi, A.M.; Pfanner, L.; Pecini, C.; Salvadorini, R.; Casalini, C.; Brizzolara, D.; Cipriani, P. Which linguistic measures distinguish transient from persistent language problems in Late Talkers from 2 to 4 years? A study on Italian speaking children. Res. Dev. Dis. 2019, 89, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescorla, L.; Alley, A. Validation of the language development survey (LDS): A parent report tool for identifying language delay in toddlers. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2001, 44, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.; Onofrio, D.; Remi, L.; Caselli, M.C. Prediction and persistence of late talking: A study of Italian toddlers at 29 and 34 months. Res. Dev. Dis. 2018, 75, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsch, C.; Richels, C.; Saldana, M.; Coleman, C.; Wimberly, C.; Maxwell, L. Narrative skill and syntactic complexity in school-age children with and without late language emergence. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2012, 47, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.; Taylor, C.; Zubrick, S. Language outcomes of 7-year-old children with or without a history of late language emergence at 24 months. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Robinson, M.; Zubrick, S.R. Late talking and the risk for psychosocial problems during childhood and adolescence. Pediatrics 2011, 128, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rescorla, L. Language and reading outcomes to age 9 in late-talking toddlers. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2002, 45, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescorla, L. Age 17 language and reading outcomes in late-talking toddlers: Support for a dimensional perspective on language delay. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2009, 52, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowling, M.J.; Duff, F.J.; Nash, H.M.; Hulme, C. Language profiles and literacy outcomes of children with resolving, emerging, or persisting language impairments. J. Child Psychol. Psychiat. 2016, 57, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana, I.M.; Pons, F.; Eadie, P.; Ystrom, E. Trajectories of language delay from age 3 to 5: Persistence, recovery and late onset. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2014, 49, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA, American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, S.; Tomblin, B.; Law, J.; Mc Kean, C.; Mensah, F.K.; Morgan, A.; Goldfeld, S.; Nicholson, J.M.; Wake, M. Specific language impairment: A convenient label for whom? Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2014, 49, 416–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bishop, D.M.V.; Edmunson, A. Specific Language Impairment as a maturational lag: Evidence from longitudinal data on language and motor development. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1987, 29, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, L.B.; Schwartz, R.G.; Chapman, K.; Rowan, L.E.; Prelock, P.A.; Terrell, B.; Weiss, A.L.; Messick, C. Early lexical acquisition in children with specific language impairment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1982, 25, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, L.B.; Sabbadini, L.; Volterra, V. Specific language impairment in children: A cross-linguistic study. Brain Lang. 1987, 32, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.M. Case history risk factors for specific language impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Lang. Path. 2017, 26, 991–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, M.; Pierpont, E. Specific language impairment is not specific to language: The procedural deficit hypothesis. Cortex 2005, 41, 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, J.A.; Conti-Ramsden, G.; Page, G.; Ullman, D.M.T. Working, declarative and procedural memory in specific language impairment. Cortex 2012, 48, 1138–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.C.S.; McPhillips, M. Comorbid motor deficits in a clinical sample of children with specific language impairment. Res. Dev. Dis. 2013, 34, 2533–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duinmeijer, I.; de Jong, J.; Scheper, A. Narrative abilities, memory and attention in children with a specific language impairment. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2012, 47, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, A. Introduzione: Le funzioni esecutive nei Disturbi (Primari) del Linguaggio. In Funzioni Esecutive nei Disturbi di Linguaggio; Marotta, L., Mariani, E., Pieretti, M., Eds.; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2017; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D.M.V.; Snowling, M.G.; Thompson, P.A.; Greenhalgh, T.; The Catalise-2 Consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiat. All. Discip. 2017, 58, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomblin, J.B.; Zhang, X.; Buckwalter, P.; O’Brien, M. The stability of primary language disorder: Four years after kindergarten diagnosis. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2003, 46, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communication & Language Acquisition Studies in Typical & Atypical Populations (CLASTA); Federazione Logopedisti Italiani (FLI) (Eds.) Consensus Conference sul Disturbo Primario del Linguaggio; CLASTA: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 1–58. Available online: https://www.disturboprimariolinguaggio.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Documento-Finale-Consensus-Conference-2.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Chilosi, A.M.; Brizzolara, D.; Lami, L.; Pizzoli, C.; Gasperini, F.; Pecini, C.; Cipriani, P.; Zoccolotti, P. Reading and spelling disabilities in children with and without a history of early language delay: A neuropsychological and linguistic study. Child Neuropsychol. 2009, 15, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantiani, C.; Lorusso, M.L.; Perego, P.; Molteni, M.; Guasti, M.T. Developmental dyslexia with and without language impairment: ERPs reveal qualitative differences in morphosyntactic processing. J. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2015, 40, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti-Ramsden, G.; St Clair, M.C.; Pickles, A.; Durkin, K. Developmental trajectories of verbal and nonverbal skills in individuals with a history of specific language impairment: From childhood to adolescence. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2012, 55, 1716–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, K.; Mok, P.L.H.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Severity of specific language impairment predicts delayed development in number skills. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Catts, H.W.; Fey, M.E.; Tomblin, J.B.; Zhang, X. A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2002, 45, 1142–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomblin, J.B.; Zhang, X.; Buckwalter, P.; Catts, H. The association of reading disability, behavioral disorders, and language impairment among second-grade children. J Child Psychol. Psychiat. 2000, 41, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti-Ramsden, G.; Mok, P.L.; Pickles, A.; Durkin, K. Adolescents with a history of specific language impairment (SLI): Strengths and difficulties in social, emotional and behavioral functioning. Res. Dev. Dis. 2013, 34, 4161–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowling, M.J.; Bishop, D.V.M.; Stothard, S.E.; Chipchase, B.; Kaplan, C. Psychosocial outcomes at 15 years of children with a preschool history of speech-language impairment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiat. 2006, 47, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, J.; Hollis, C.; Mawhood, L.; Rutter, M. Developmental language disorders—A follow-up in later adult life. Cognitive, language and psychosocial outcomes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiat. 2005, 46, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Clair, M.; Pickles, A.; Durkin, K.; Conti-Ramsden, G. A longitudinal study of behavioral, emotional and social difficulties in individuals with a history of specific language impairment (SLI). J. Comm. Dis. 2011, 44, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Law, J.; Rush, R.; Schoon, I.; Parsons, S. Modeling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood: Literacy, mental health, and employment outcomes. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2009, 52, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stothard, S.E.; Snowling, M.J.; Bishop, D.V.M.; Chipchase, B.B.; Kaplan, C.A. Language-impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1998, 41, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomblin, J.B. Validating diagnostic standards for specific language impairment using adolescent outcomes. In Understanding Developmental Language Disorders: From Theory to Practice; Norbury, C.F., Tomblin, J.B., Bishop, D.V.M., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- CADTH. Screening Tools Compared to Parental Concern for Identifying Speech and Language Delays in Preschool Children: A Review of the Diagnostic Accuracy; Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding, T.J.; Plante, E.; Farinella, K.A. Eligibility criteria for language impairment: Is the low end of normal always appropriate? Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2006, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.; Garrett, Z.; Nye, C. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and language delay or disorder. Cochr. Datab. System. Rev. 2003, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, D.B. A systematic review of narrative-based language intervention with children who have language impairment. Comm. Dis. Quart. 2011, 32, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favot, K.; Carter, M.; Stephenson, J. The effects of oral narrative intervention on the narratives of children with language disorder: A systematic literature review. J. Dev. Phys. Dis. 2020, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.R. Phonological treatment options for children with expressive language impairment. Sem. Speech Lang. 2019, 40, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.W.; Magimairaj, B.M.; Finney, M.C. Working memory and specific language impairment: An update on the relation and perspectives on assessment and treatment. Am. J. Lang. Path. 2010, 19, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellon-Harn, M.L.; Morris, L.R.; Manchaiah, V.; Harn, W.E. Use of videos and digital media in parent-implemented interventions for parents of children with primary speech sound and/or language disorders: A scoping review. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirrin, F.M.; Schooling, T.L.; Nelson, N.W.; Diehl, S.F.; Flynn, P.F.; Staskowski, M.; Torrey, T.Z.; Adamczyk, D.F. Evidence-based systematic review: Effects of different service delivery models on communication outcomes for elementary school–age children. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2010, 41, 233–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Candiani, G.; Colombo, C.; Daghini, R. Manuale Metodologico: Come Organizzare una Conferenza di Consenso (Engl. Transl: Methodological Manual: How to Organize a Consensus Conference). Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Sistema Nazionale Linee Guida (SNLG), Roma. 2013. Available online: https://www.socialesalute.it/res/download/maggio2012/consensus_conference.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shea, B.J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Wells, G.A.; Boers, M.; Andersson, N.; Hamel, C.; Bouter, L.M. Development of AMSTAR: A measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Method. 2007, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, M.M. Intervention efficacy and intensity for children with speech sound disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013, 56, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lousada, M.; Jesus, L.M.; Capelas, S.; Margaca, C.; Simoes, D.; Valente, A.; Hall, A.; Joffe, V.L. Phonological and articulation treatment approaches in Portuguese children with speech and language impairments: A randomized controlled intervention study. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2013, 48, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diaz-Williams, P. Using Movement Homework Activities to Enhance the Phonological Skills of Children Whose Primary Communication Difficulty is a Phonological Disorder. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wren, Y.; Roulstone, S. A comparison between computer and tabletop delivery of phonology therapy. Int. J. Speech Lang. Path. 2008, 10, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, L.M.; Martinez, J.; Santos, J.; Hall, A.; Joffe, V. Comparing traditional and tablet-based intervention for children with speech sound disorders: A randomized controlled trial. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2019, 62, 4045–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roden, I.; Früchtenicht, K.; Kreutz, G.; Linderkamp, F.; Grube, D. Auditory stimulation training with technically manipulated musical material in preschool children with specific language impairments: An explorative study. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, D.J.H.; van Dijken, M.J.; Bus, A.G. Using electronic storybooks to support word learning in children with severe language impairments. J. Learn. Dis. 2014, 47, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plante, E.; Ogilive, T.; Vance, R.; Aguilar, J.M.; Dailey, N.S.; Meyers, C.; Lieser, A.M.; Burton, R. Variability in the language input to children enhances learning in a treatment context. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Path 2013, 23, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, M.E.; Leonard, L.B.; Bredin-Oja, S.L.; Deevy, P. A Clinical evaluation of the competing sources of input hypothesis. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2017, 60, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith-Lock, K.M.; Leitao, S.; Prior, P.; Nickels, L. The effectiveness of two grammar treatment procedures for children with SLI: A randomized clinical trial. Lang Speech Hear Ser. Sch. 2015, 46, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Washington, K.N.; Warr-Leeper, G.; Thomas-Stonell, N. Exploring the outcomes of a novel computer-assisted treatment program targeting expressive- grammar deficits in preschoolers with SLI. J. Comm. Dis. 2011, 44, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, K.N.; Warr-Leeper, G. Visual support in intervention for preschoolers with specific language impairment. Top. Lang. Dis. 2013, 33, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoder, P.J.; Molfese, D.; Gardner, E. Initial mean length of utterance predicts the relative efficacy of two grammatical treatments in preschoolers with specific language impairment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2012, 54, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finestack, L.H.; Fey, M.E. Evaluation of a deductive procedure to teach grammatical inflections to children with language impairment. Am. J. Speech Lang. Path. 2009, 18, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finestack, L.H. Evaluation of an Explicit Intervention to Teach Novel Grammatical Forms to Children with Developmental Language Disorder. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2018, 61, 2062–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.A.; Lewis, K.E.; Haskill, A.; Tolbert, L.C. Efficacy and cross-domain effects of a morphosyntax and a phonology intervention. Lang Speech Hear Ser. Sch. 2002, 33, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiolo, M.; Pavez, M.M.; Coloma, C.J. Terapia para eldesarrollo narrativo en niños con trastornoespecífico del lenguaje (Eng. Transl: Narrative intervention for children with specific language impairment). Rev. Logop. Foniatr. Audiol. 2003, 23, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, E.; Leitão, S.; Claessen, M.; Kane, R. A randomized controlled trial of an oral inferential comprehension intervention for young children with developmental language disorder. Child Lang. Teach. Ther. 2019, 35, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, A.; Dima, E.; Nelson, V. Teaching phoneme awareness to pre-literate children with speech disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2007, 42, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund-Reid, C.; Schneider, P. Effectiveness of phonological awareness intervention for kindergarten children with language impairment. Can. J. Speech Lang. Path. Aud. 2013, 37, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M.Y.; Kaiser, A.P. Assessing the effects of a parent-implemented language intervention for children with language impairments using empirical benchmarks: A pilot study. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2012, 55, 1655–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, M.; Tobin, S.; Levickis, P.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Zens, N.; Goldfeld, S.; Le, H.; Law, J.; Reilly, S. Randomized trial of a population-based, home delivered intervention for preschool language delay. Pediatrics 2013, 132, e895–e904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wake, M.; Tobin, S.; Levickis, P.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Zens, N.; Goldfeld, S.; Le, H.; Law, J.; Reilly, S. Two-year outcomes of a population-based intervention for preschool language delay: An RCT. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e838–e847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilcox, M.J.; Gray, S.; Reiser, M. Preschoolers with developmental speech and/or language impairment: Efficacy of the Teaching Early Literacy and Language (TELL) curriculum. Early Child. Res. Quart. 2020, 51, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, R.B.; Loeb, D.F.; Hoffman, L.M.; Bohman, T.; Champlin, C.A.; Thibodeau, L.; Friel-Patti, S. The efficacy of Fast ForWord language intervention in school-age children with language impairment: A randomized controlled trial. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, W.; Hodson, A.; O’Hare, A.; Boyle, J.; Durrani, T.; McCartney, E.; Watson, J. Effects of computer-based intervention through acoustically modified speech (Fast ForWord) in severe mixed receptive-expressive language impairment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2005, 48, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, J.H.Y.; Bamiou, D.E.; Campbell, N.; Luxon, L.M. Computer-based auditory training (CBAT): Benefits for children with language-and reading-related learning difficulties. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodson, D.W. Hodson Assessment of Phonological Patterns, 3rd ed.; PRO-ED: Austin, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, R.; Fristoe, M. Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation 2; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fox-Boyer, A.V. TROG-D: Test zur Überprüfung des Grammatikverständnisses; Schulz-Kirchner Verlag GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Lock, K.M.; Leitão, S.; Lambert, L.; Nickels, L. Effective intervention for expressive grammar in children with specific language impairment. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Dis. 2013, 48, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, O.E.; Kresheck, J.D. The Structured Photographic Expressive Language Test-Preschool (SPELT-P); Janelle Publications Inc.: Dekalb, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.L. Developmental Sentence Analysis: A Grammatical Assessment Procedure for Speech and Language Clinicians; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Blachman, B.A.; Ball, E.W.; Black, R.; Tangel, D.M. Road to the Code: A phonological Awareness Program for Young Children, 5th ed.; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wake, M.; Tobin, S.; Girolametto, L.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Gold, L.; Levickis, P.; Sheehan, J.; Goldfeld, S.; Reilly, S. Outcomes of population based language promotion for slow to talk toddlers at ages 2 and 3 years: Let’s Learn Language cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011, 343, d4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goldfeld, S.; Quach, J.; Nicholls, R.; Reilly, S.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; Wake, M. Four-year-old outcomes of a universal infant-toddler shared reading intervention: The let’s read trial. Arch Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilcox, M.J.; Gray, S.; Guimond, A.B.; Lafferty, A.E. Efficacy of the TELL language and literacy curriculum for preschoolers with developmental speech and/or language impairment. Early Chil. Res. Quart. 2011, 26, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Learning Corporation. Fast ForWord-Language [Computer Software]; Scientific Learning Corporation: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, L.M.T.; Lousada, M. Protocolo de Anamnese de Linguagem na Criança da Universidade de Aveiro [University of Aveiro’s Case History Form for Child Language]. In INPI Registration Number 465220 and IGAC Registration 2 June 2010; University of Aveiro: Aveiro, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, A.; Afonso, E.; Lousada, M.; Andrade, F. Teste Fonético-Fonologico ALPE [Phonetic-Phonological Test]; Edubox: Aveiro, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, A.; Afonso, E.; Lousada, M.; Andrade, F. Teste de Linguagem ALPE [Language Test]; Edubox: Aveiro, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, I. Protocolo de Avaliação Orofacial [Oro-Motor Structure and Function Test]; Fisiopraxis: Lisbon, Portugal, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schöler, H.; Brunner, M. Heidelberger Auditives Screening in Der Einschulungsuntersuchung; Westra: Franeker, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kort, W.; Schittekatte, M.; Compaan, E. CELF-4-NL: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—Vierde-Editie; Pearson: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, S.F. Enhancing communication and language development with milieu teaching procedures. In A Guide for Developing Language Competence in Pre-School Children with Severe and Moderate Handicaps; Cipani, E., Ed.; Charles C Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 1991; pp. 68–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, P.; Camarata, S.; Gardner, E. Treatment effects on speech intelligibility and length of utterance in children with specific language and intelligibility impairments. J. Early Interv. 2005, 28, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon, G. The Gillon Phonological Awareness Training Programme: An Intervention for Children at Risk of Reading Disorder. Programme Handbook; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, E.C. The Hidden Language Skill: Oral Inferential Comprehension in Children with Developmental Language Disorder. School of Psychology and Speech Pathology; Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University: Perth, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://espace.curtin.edu.au/handle/20.500.11937/56528 (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Dawes, E.; Leitão, S.; Claessen, M.; Kane, R. Peter and the Cat Narrative Comprehension Assessment (NCA); Black Sheep Press: Keighley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, B.; Crosbie, S.; Macintosh, B.; Teitzel, T.; Ozanne, A. Pre-School and Primary Inventory of Phonological Awareness; Psychological Corporation: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, E.; Howell, J.; Hill, A.; Waters, D. Metaphon Resource Pack; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, L.; Hancock, C.; Smartt, S. DIBELS the Practical Manual; Sopris West Educational Services: Longmont, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, I.; Steiner, V.; Pond, R. Preschool Language Scale, 4th ed.; Harcourt Assessment: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Semel, E.; Wiig, E.H.; Secord, W.A. Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals, 3rd ed.; Psychological Corporation: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan, C.J.; Wagner, R.; Torgesen, J.; Rashette, C. Test of Preschool Literacy; Pro-Ed, Inc.: Austin, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Invernizzi, M.; Sullivan, A.; Meier, J.; Swank, L.; Jones, B. Teacher’s Manual PreK: Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening. 2004. Available online: https://pals.virginia.edu/pdfs/rd/tech/PreK_technical_chapter.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Carrow-Woolfolk, E. Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DiSimoni, F. The Token Test for Children; Riverside: Rolling Meadows, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, R.K.; Torgesen, J.K.; Rashotte, C.A. Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing; Pro-Ed.: Austin, TX, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer, P.L.; Hammill, D.D. Test of Language Development—Primary, 3rd ed.; Pro-Ed.: Austin, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson, N.; Frith, U.; Reason, R. Phonological Assessment Battery; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, C. Bus Story Test, 4th ed.; Winslow Press: Bicester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| INCLUSION CRITERIA | |

|---|---|

| POPULATION | Preschool and primary school children (up to 8 years of age) diagnosed with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) |

| INTERVENTION | Any type of intervention that aims to improve the child’s skills in the phono-articulatory, phonological, semantic-lexical and morpho-syntactic fields. The intervention can be administered at the individual or group level, by different types of professional figures (teacher, health care personnel, parents, speech therapists, other health care professionals), with different durations and frequencies, in different settings (home, clinics, community, school). |

| COMPARISONS | Other types of experimental interventions, waiting list, no intervention, other interventions that are considered “usual care”. |

| OUTCOMES |

|

| SETTING | Any setting |

| STUDY DESIGN | Systematic reviews (SR) or meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), RCTs. If no RCTs are available: cohort studies. We considered only SR that (1) searched at least one database; (2) reported its selection criteria; (3) conducted quality or risk of bias assessment on included studies; and (4) provided a list and synthesis of included studies. SRs that identified observational studies were included if results from RCTs were provided separately. |

| LIMITS |

|

| EXCLUSION CRITERIA | Children with cognitive delay, deafness, autism spectrum disorders, genetic syndromes (Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome), neurological deficits, pervasive developmental disorders, traumatic brain injuries, primary disorders (sensory, neurological, psychiatric), children with dysphonia, dysarthria, dysrhythmias or stuttering, dyslalias or specific speech articulation disorder, bilingualism. Commentaries, opinions, editorials and studies that do not report a quantitative synthesis of the association between intervention and outcome measures. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rinaldi, S.; Caselli, M.C.; Cofelice, V.; D’Amico, S.; De Cagno, A.G.; Della Corte, G.; Di Martino, M.V.; Di Costanzo, B.; Levorato, M.C.; Penge, R.; et al. Efficacy of the Treatment of Developmental Language Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11030407

Rinaldi S, Caselli MC, Cofelice V, D’Amico S, De Cagno AG, Della Corte G, Di Martino MV, Di Costanzo B, Levorato MC, Penge R, et al. Efficacy of the Treatment of Developmental Language Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(3):407. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11030407

Chicago/Turabian StyleRinaldi, Sara, Maria Cristina Caselli, Valentina Cofelice, Simonetta D’Amico, Anna Giulia De Cagno, Giuseppina Della Corte, Maria Valeria Di Martino, Brigida Di Costanzo, Maria Chiara Levorato, Roberta Penge, and et al. 2021. "Efficacy of the Treatment of Developmental Language Disorder: A Systematic Review" Brain Sciences 11, no. 3: 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11030407

APA StyleRinaldi, S., Caselli, M. C., Cofelice, V., D’Amico, S., De Cagno, A. G., Della Corte, G., Di Martino, M. V., Di Costanzo, B., Levorato, M. C., Penge, R., Rossetto, T., Sansavini, A., Vecchi, S., & Zoccolotti, P. (2021). Efficacy of the Treatment of Developmental Language Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sciences, 11(3), 407. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11030407