Secondary Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Fatigue, Self-Compassion, Physical and Mental Health of People with Multiple Sclerosis and Caregivers: The Teruel Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Experimental Design

2.2. Procedures and Variables of Study

2.3. Evaluation Instruments

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Descriptives of People with MS and Caregivers

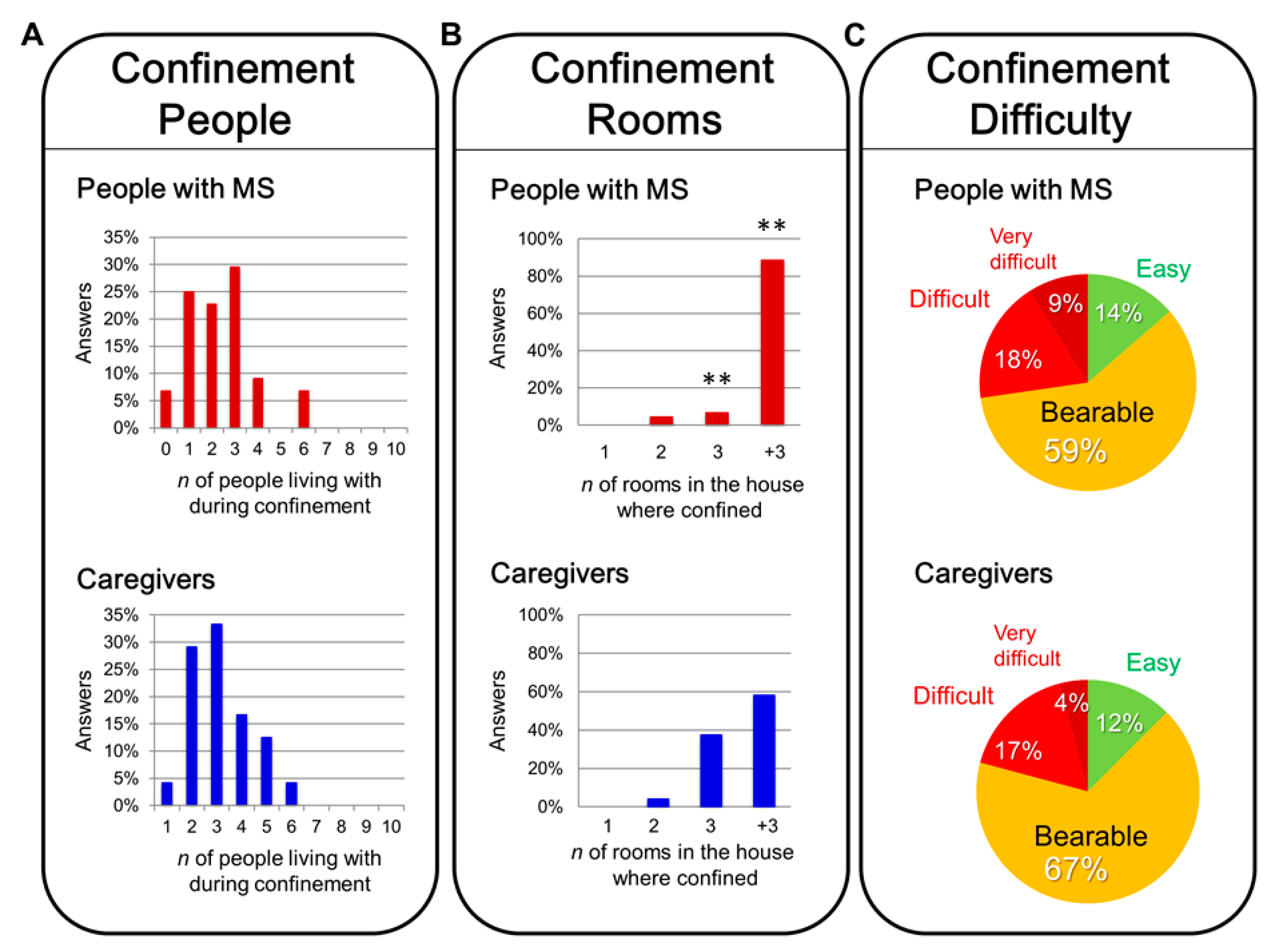

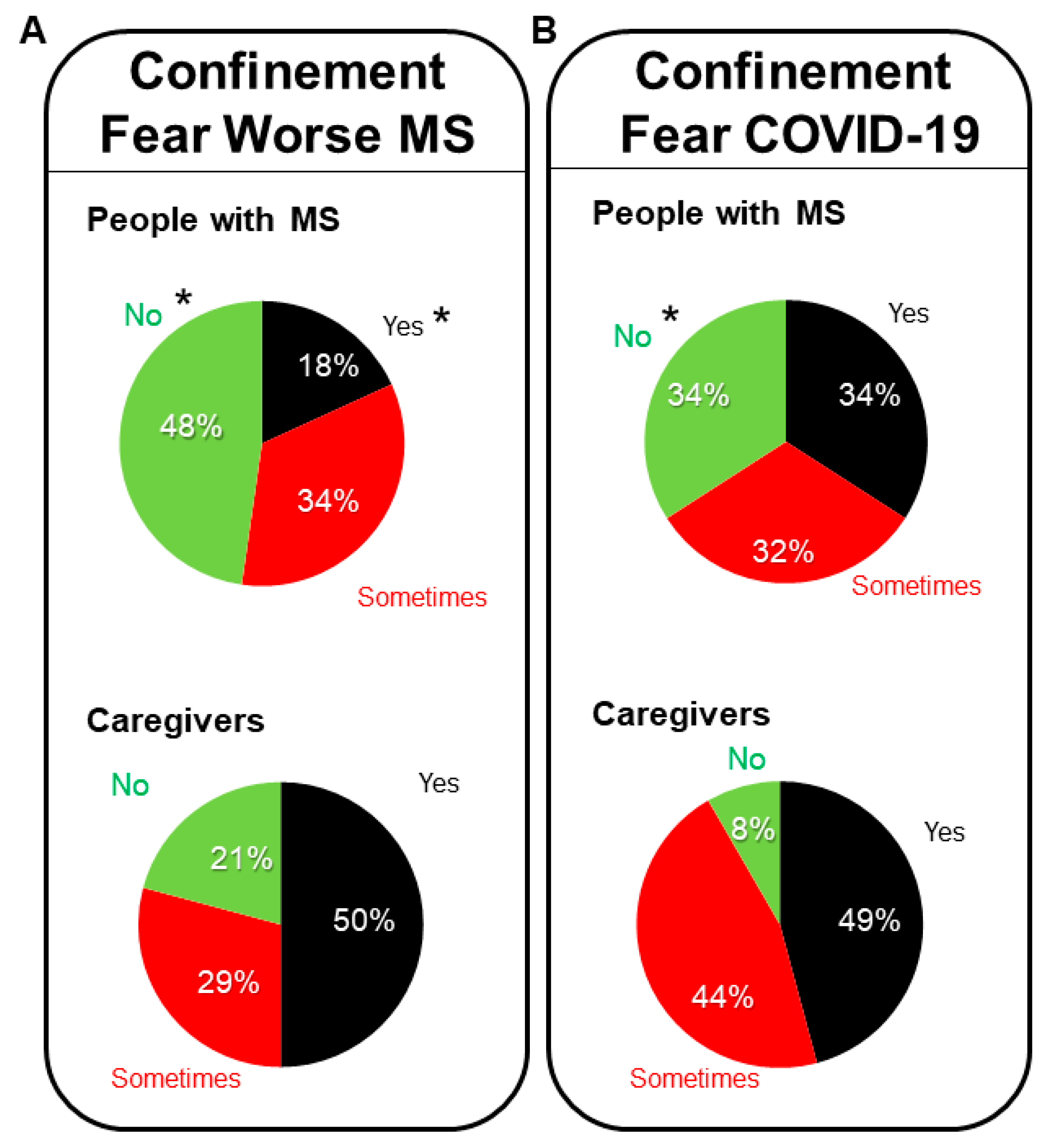

3.2. COVID-19, Confinement and Fears

3.3. Fatigue, Self-Compassion, and Compassion in People with MS and Caregivers

3.4. Correlations between Self-Compassion in People with MS and Compassion in Caregivers with Physical and Mental Health, including Fatigue

3.5. Regression Analysis of Self-Compassion in People with MS, and Compassion in Caregivers

4. Discussion and Implications

4.1. Sociodemography, COVID-19 Confinement and Fears

4.2. Fatigue, Self-Compassion, and Compassion in People with MS and Caregivers

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Self-compassion evaluated after the post-confinement in the months of June–July 2020 of the MS patients remained at a moderate–high level.

- (2)

- MS patients perceived their physical and emotional health during June–July 2020 as at medium and moderate levels.

- (3)

- The fatigue of MS patients during June–July 2020 presented high scores, mainly in physical and cognitive fatigue.

- (4)

- The self-compassion of the group of MS patients significantly correlated with fatigue and global health (physical and emotional) and presented explanatory validity with a 19% variance of global health.

- (5)

- The high compassion of the caregivers of MS patients did not show relationships with any physical or emotional health variable, nor with fatigue scales.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Monitoring and Mitigating the Secondary Impacts of The Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic on WASH Services Availability and Access. UNICEF Technical Note. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/monitoring-and-mitigating-secondary-impacts-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-pandemic-wash (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health & COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/covid-19 (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Giménez-Llort, L. The key role of chronosystem in the socio-ecological analysis of COVID. In Proceedings of the Actas del VII Congreso Internacional de Investigación en Salud, Madrid, Spain, 24–25 September 2020; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Montemurro, N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: From medical staff to common people. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.Y.; Kok, A.; Eikelenboom, M.; Horsfall, M.; Jörg, F.; Luteijn, R.A.; Rhebergen, D.; Oppen, P.V.; Giltay, E.J.; Penninx, B. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: A longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, T.V.; Bu, F.; Dissing, A.S.; Elsenburg, L.K.; Bustamante, J.; Matta, J.; van Zon, S.; Brouwer, S.; Bültmann, U.; Fancourt, D.; et al. Loneliness, worries, anxiety, and precautionary behaviours in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal analysis of 200,000 Western and Northern Europeans. Lancet Reg. Health. Eur. 2021, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invitto, S.; Romano, D.; Garbarini, F.; Bruno, V.; Urgesi, C.; Curcio, G.; Grasso, A.; Pellicciari, M.C.; Kock, G.; Betti, V.; et al. Major stress-related symptoms during the lockdown: A study by the Italian Society of Psychophysiology and Cognitive Neuroscience. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 636089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoszek, A.; Walkowiak, D.; Bartoszek, A.; Kardas, G. Mental well-being (depression, loneliness, insomnia, daily life fatigue) during COVID-19 related home-confinement—A study from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Confinement and the hatred of sound in times of COVID-19: A Molotov cocktail for people with misophonia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 627044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Sound of silence in times of COVID-19: Distress and loss of cardiac coherence in people with Misophonia by real, imagined or evoked trigger sounds. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 638949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montemurro, N. Intracranial hemorrhage and COVID-19, but please do not forget “old diseases” and elective surgery. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 92, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustin, L.; Wagner, L. The butterfly effect of caring—Clinical nursing teachers understanding of self-compassion as a source to compassionate care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2013, 27, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, L.; Curry, J. Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2011, 15, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neff, K. The science of self-compassion. In Compassion and Wisdom in Psychotherapy; En, C., Siegel, G.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bluth, K.; Roberson, P.; Gaylord, S. A pilot study of a mindfulness intervention for adolescents and the potential role of self-compassion in reducing stress. Explore 2015, 11, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, D.S.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Calabresi, P.A. Multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Baranzini, S.E.; Geurts, J.; Hemmer, B.; Ciccarelli, O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2018, 391, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.L. Cognitive deficits in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2010, 68, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- González-Siles, P. Bases Cerebrales de la Fatiga en Pacientes de Esclerosis Múltiple. Una Revisión Bibliográfica; TFM Universitat Jaume I: Valencia, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa-Frossard, L.; Moreno-Torres, I.; Meca-Lallana, V.; García-Domínguez, J.M. Documento EMCAM (Esclerosis Múltiple Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid) para el manejo de pacientes con esclerosis múltiple durante la pandemia de SARS-CoV-2. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 70, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghmousavi, S.; Rezaei, N. COVID-19 and multiple sclerosis: Predisposition and precautions in treatment. SN Compr. Clin. Medicine 2020, 2, 1802–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.A. Looking ahead: The risk of neurologic complications due to COVID-19. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2020, 10, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Louapre, C.; Collongues, N.; Stankoff, B.; Giannesini, C.; Papeix, C.; Bensa, C.; Deschamps, R.; Créange, A.; Wahab, A.; Pelletier, J.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed, M.; Sahraian, M.A.; Rezaeimanesh, N.; Naser, A. psychiatric advice during COVID-19 pandemic for patients with multiple sclerosis. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2020, 14, e103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moss, B.P.; Mahajan, K.R.; Bermel, R.A.; Hellisz, K.; Hua, L.H.; Hudec, T.; Husak, S.; McGinley, M.P.; Ontaneda, D.; Wang, Z.; et al. Multiple sclerosis management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, W.I.; Compston, A.; Edan, G.; Goodkin, D.; Hartung, H.P.; Lublin, F.; McFarland, H.; Paty, D.; Polman, C.; Reingold, S.; et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple Sclerosis: Guidelines from the international panel on the diagnosis of multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2001, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, C.; Reingold, S.; Edan, G.; Filippi, M.; Hartung, H.P.; Kappos, L.; Lublin, F.; Metz, L.; McFarland, H.; O’Connor, P.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alonso, J.; Prieto, L.; Anto, J.M. La versión española del SF-36 Health Survey (Cuestionario de Salud SF-36): In instrumento para la medida de los resultados clínicos. Med. Clin. 1995, 104, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neff, K. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2003, 3, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Campayo, J.; Navarro-Gill, M.; Andrés, E.; Montero-Marin, J.; López-Artal, L.; Demarzo, M. Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychothe. 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommier, E.A. The Compassion Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, G. Cultivating Healthy Minds and Open Hearts: A Mixed-Method Controlled Study on the Psychological and Relational Effects of Compassion Cultivation Training in Chile. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kos, D.; Kerckhofs, E.; Carrea, I.; Verza, R.; Ramos, M.; Jansa, J. Evaluation of the modified fatigue impact scale in four different European countries. Mult. Scler. J. 2005, 11, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.D. Psychometric properties of the modified fatigue impact scale. Int. J. MS Care 2013, 15, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fisk, J.D.; Doble, S.E. Construction and validation of fatigue impact scale for daily administration (D-FIS). Qual. Life Res. 2002, 11, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, K.; Schmidt, K.; Marangoni, B.; Mendes, M.F.; Tilbery, C.P.; Lianza, S. Multiple sclerosis: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the modified fatigue impact scale. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2007, 65, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldenberg, M. Multiple sclerosis review. Pharm. Ther. 2012, 37, 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Borghi, M.; Cavallo, M.; Carletto, S.; Ostacoli, L.; Zuffranieri, M.; Picci, R.L.; Scavelli, F.; Johnston, H.; Furlan, P.M.; Bertolotto, A.; et al. Presence and significant determinants of cognitive impairment in a large sample of patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, G.X.; Sanabria, C.; Martínez, D.; Zhang, W.T.; Gao, S.S.; Alemán, A.; Granja, A.; Páramo, C.; Borges, M.; Izquierdo, G. Social and professional consequences of COVID-19 lockdown in patients with multiple sclerosis from two very different populations. Consecuencias sociolaborales del confinamiento por la COVID-19 en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple en dos poblaciones muy diferentes. Neurologia 2021, 36, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, G.; Lamura, G.; Principi, A. Valuing and integrating informal care as a core component of long-term care for older people: A comparison of recent developments in Italy and Spain. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2017, 29, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Parente, A.F. Subjectivity around grandparents and other elderly people determines divergence of opinion as to the importance of older people living in family or in nursing homes. EC Neurol. 2019, 11.10, 968–976. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmazane, M.; Gallou-Guyot, M.; Compagnat, M.; Magy, L.; Montcuquet, A.; Billot, M.; Daviet, J.C.; Perrochon, A. Effects on gait and balance of home-based active video game interventions in persons with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 51, 102928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limbers, C.A.; McCollum, C.; Greenwood, E. Physical activity moderates the association between parenting stress and quality of life in working mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 19, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguera-García, M.M.; Liébana-Presa, C.; Álvarez-Barrio, L.; Alves Gomes, L.; Fernández-Martínez, E. Physical activity, resilience, sense of coherence and coping in people with multiple sclerosis in the situation derived from COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, N.; Río, J.; Tintoré, M.; Nos, C.; Galán, I.; Montalban, X. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis persists overtime: A longitudinal study. J. Neurol. 2006, 253, 1466–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerdal, A.; Gullowsen, E.; Krupp, L.; Dahl, A.A. A prospective study of patterns of fatigue in multiple Sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreu-Caravaca, L.; Ramos-Campo, D.; Manonelles, P.; Abellán-Aynés, O.; Chung, L.H.; Rubio-Arias, J.Á. Effect of COVID-19 home confinement on sleep monitorization and cardiac autonomic function in people with multiple sclerosis: A prospective cohort study. Physiol. Beh. 2021, 237, 113392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, G. Mindfulness y Auto-Compasión: Un Estudio Correlacional en Estudiantes Universitarios. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Chile, Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Sanderman, R.; Smink, A.; Zhang, Y.; Van Sonderen, E.; Ranchor, A.; Schoevers, M. A reconsideration of the self-compassion scale’s total score: Self-Compassion versus self-criticism. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reyes, M. Self-compassion: A concept analysis. J. Holist. Nurs. 2012, 30, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, L.; Kyeong, L. Self-compassion as a moderator of the relationship between academic burn-out and psychological health in Korean cyber university students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 54, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertson, E.; Neff, K.; Dill-Shackleford, K. Self-compassion and body dissatisfaction in women: A randomized controlled trial of a brief meditation intervention. Mindfulness 2014, 6, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnell, L.; Stafford, R.; Neff, K.; Reilly, E.; Knox, M.; Mullarkey, M. Metaanalysis of gender differences in self-compassion. Self Identity 2015, 14, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; McEwan, K.; Irons, C.; Bhundia, R.; Christie, R.; Broomhead, C.; Rockliff, H. Self-harm in a mixed clinical population: The roles of self-criticism, shame, and social rank. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 49, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longe, O.; Maratos, F.; Gilbert, P.; Eans, G.; Volker, F.; Rockliff, H.; Rippon, G. Having a word with yourself: Neural correlates of selfcriticism and self-reassurance. Neuroimage 2010, 49, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, C. On Becoming a Person: A therapist’s View of Psychotherapy; Boston Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, P.; McEwan, K.; Gibbons, L.; Chotai, S.; Duarte, J.; Matos, M. Fears of compassion and happiness in relation to alexithymia, mindfulness, and self-criticism. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 85, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poch, C.; Vicente, A. La acogida y la compasión: Acompañar al otro. In Los Márgenes de la Moral: Una Mirada Etica a la Educación; Mèlich, J.C., Boixader, A., Eds.; Editorial Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Lazarus, B.N. Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions; Oxford University: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Regner, E. Compasión y gratitud, emociones empáticas que elicitan las conductas prosociales. In Investigación en Ciencias del Comportamiento. Avances Iberoamericanos; Richaud, M.C., Moreno, J.E., Eds.; CIIPME—CONICET: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadillo, R.E.; Díaz, J.L.; Barrios, F.A. Neurobiología de las emociones morales. Salud Ment. 2007, 30, 1–11. Available online: http://www.revistasaludmental.mx (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Ostrosky-Solís, F.; Vélez-García, A.E. Neurobiología de la sensibilidad moral. Rev. Neuropsicol. Neuropsiquiatría Neurocienc. 2008, 8, 115–126. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Kirby, J.N. Compassion interventions: The programmes, the evidence and implications for research and practice. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 90, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Procter, S. Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germer, C.K.; Neff, K.D. Self-compassion in clinical practice. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, C.; Taylor, B.L.; Gu, J.; Kuyken, W.; Baer, R.; Jones, F.; Cavanagh, K. What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 47, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| People with MS | Caregivers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 44 | N = 24 | ||||

| Frequencies | % | Frequencies | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 31 | 70.45 | 16 | 66.67 |

| Male | 13 | 29.55 | 8 | 33.34 | |

| Age | <36 years | 2 | 4.55 | 7 | 29.16 |

| de 36 a 45 | 10 | 22.73 | 2 | 8.34 | |

| de 46 a 55 | 21 | 47.73 | 9 | 37.5 | |

| >55 years | 11 | 25.00 | 6 | 25 | |

| Marital status | Married/living with partner | 35 | 79.55 | 17 | 70.83 |

| Single | 6 | 13.64 | 7 | 29.17 | |

| Separated/divorced | 3 | 6.82 | - | - | |

| Living arrangements | Lives alone | 4 | 9.09 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Lives with partner/spouse | 15 | 34.09 | 11 | 45.84 | |

| Lives with partner/spouse and children | 19 | 43.18 | 8 | 33.34 | |

| Lives with other family | 6 | 13.64 | 1 | 4.16 | |

| Other | - | - | 1 | 4.16 | |

| Education | No qualifications | 1 | 2.27 | ||

| Primary school | 8 | 18.18 | 5 | 20.83 | |

| Secundary school | 13 | 29.55 | 9 | 37.5 | |

| University | 22 | 50.00 | 10 | 41.67 | |

| Employment situation | Student | 4 | 16.67 | ||

| Homemaker | 2 | 4.55 | 1 | 4.17 | |

| Unemployed | 1 | 2.27 | - | - | |

| Employed | 10 | 22.73 | 11 | 45.83 | |

| Temporary unemployed | 1 | 2.27 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Retired | 13 | 29.55 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Permanent disability | 12 | 27.27 | 1 | 4.17 | |

| Other | 5 | 11.36 | 1 | 4.17 | |

| People with MS (N = 44) | Mean | Median | SD | Range | Min | Max | 95% (IC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Compassion | 3.22 | 3.16 | 0.565 | 2.08 | 2.25 | 4.33 | 3.05–3.39 |

| Physical function | 20.9 | 22 | 5.838 | 20 | 10 | 30 | 19.13–22.68 |

| Physical role | 5.79 | 5.5 | 1.636 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5.29–6.29 |

| Emotional role | 5.36 | 6 | 1.122 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5.02–5.70 |

| Social function | 7.97 | 8 | 2.085 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 7.34–8.61 |

| Body pain | 7.72 | 8 | 2.433 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 6.98–8.46 |

| Vitality | 13.9 | 15 | 4.917 | 17 | 5 | 22 | 12.41–15.40 |

| General health (PCS) | 17.18 | 17 | 3.642 | 14 | 10 | 24 | 16.07–18.28 |

| Mental health (MCS) | 23.2 | 23 | 3.825 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 22.04–24.36 |

| Global health (HRQoL) | 102.1 | 103 | 17.775 | 63 | 68 | 131 | 96.66–107.47 |

| Physical fatigue | 20.18 | 23 | 8.994 | 34 | 0 | 34 | 17.44–22.91 |

| Cognitive fatigue | 15.06 | 18.5 | 9.604 | 33 | 0 | 33 | 12.14–17.98 |

| Psychosocial fatigue | 3.56 | 4 | 1.921 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 2.98–4.15 |

| Global fatigue | 38.81 | 43.5 | 17.838 | 61 | 0 | 61 | 33.39–44.24 |

| MS Caregivers (N = 24) | Mean | Median | SD | Range | Min | Max | 95% (IC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compassion | 3.84 | 3.9 | 0.442 | 1.5 | 2.96 | 4.54 | 3.65–4.03 |

| Physical function | 26.13 | 28 | 4.902 | 16 | 14 | 30 | 24.01–28.25 |

| Physical role | 6.78 | 8 | 1.565 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6.10–7.45 |

| Emotional role | 4.83 | 5 | 1.267 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4.27–5.37 |

| Social function | 7.13 | 7 | 2.262 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 6.15–8.10 |

| Body pain | 8.48 | 9 | 2.644 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 7.33–9.62 |

| Vitality | 14.65 | 15 | 3.961 | 14 | 7 | 21 | 12.93–16.36 |

| General health (PCS) | 20.35 | 21 | 4.323 | 17 | 10 | 27 | 18.47–22.21 |

| Mental health (MCS) | 20.52 | 22 | 5.265 | 22 | 7 | 29 | 18.24–22.79 |

| Global health (HRQoL) | 108.87 | 117 | 21.808 | 86 | 52 | 138 | 99.43–118.29 |

| Physical fatigue | 11.82 | 9 | 8.680 | 32 | 1 | 33 | 8.06–15.58 |

| Cognitive fatigue | 11.91 | 10 | 8.789 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 8.11–15.71 |

| Psychosocial fatigue | 2.86 | 2 | 2.399 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1.83–3.90 |

| Global fatigue | 26.60 | 23 | 18.376 | 64 | 5 | 69 | 18.66–34.55 |

| rho Self-Compassion | rho Compassion | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 0.155 | 0.247 |

| Physical role | 0.330 * | −0.011 |

| Emotional role | 0.191 | −0.054 |

| Social function | 0.387 ** | −0.052 |

| Body pain | 0.269 | −0.089 |

| Vitality | 0.456 ** | 0.084 |

| General health (PCS) | 0.296 | 0.328 |

| Mental health (MCS) | 0.278 | 0.134 |

| Global health (HRQoL) | 0.436 ** | 0.170 |

| Physical fatigue | −0.285 | 0.023 |

| Cognitive fatigue | −0.380 * | 0.132 |

| Psychosocial fatigue | −0.262 | −0.036 |

| Global fatigue | −0.455 ** | 0.040 |

| Model | R | R2 | R2 Adjusted | ESE | Chance R2 | F-Chance | gl1 | gl2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.441 | 0.194 | 0.175 | 16.144 | 0.194 | 10.129 | 1 | 42 | 0.003 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giménez-Llort, L.; Martín-González, J.J.; Maurel, S. Secondary Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Fatigue, Self-Compassion, Physical and Mental Health of People with Multiple Sclerosis and Caregivers: The Teruel Study. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091233

Giménez-Llort L, Martín-González JJ, Maurel S. Secondary Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Fatigue, Self-Compassion, Physical and Mental Health of People with Multiple Sclerosis and Caregivers: The Teruel Study. Brain Sciences. 2021; 11(9):1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091233

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiménez-Llort, Lydia, Juan José Martín-González, and Sara Maurel. 2021. "Secondary Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Fatigue, Self-Compassion, Physical and Mental Health of People with Multiple Sclerosis and Caregivers: The Teruel Study" Brain Sciences 11, no. 9: 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091233

APA StyleGiménez-Llort, L., Martín-González, J. J., & Maurel, S. (2021). Secondary Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Fatigue, Self-Compassion, Physical and Mental Health of People with Multiple Sclerosis and Caregivers: The Teruel Study. Brain Sciences, 11(9), 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11091233