The Effect of Menstrual Cycle Phases on Approach–Avoidance Behaviors in Women: Evidence from Conscious and Unconscious Processes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aims

1.2. Plan and Hypothesis

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessment Scales

2.3. Experiments

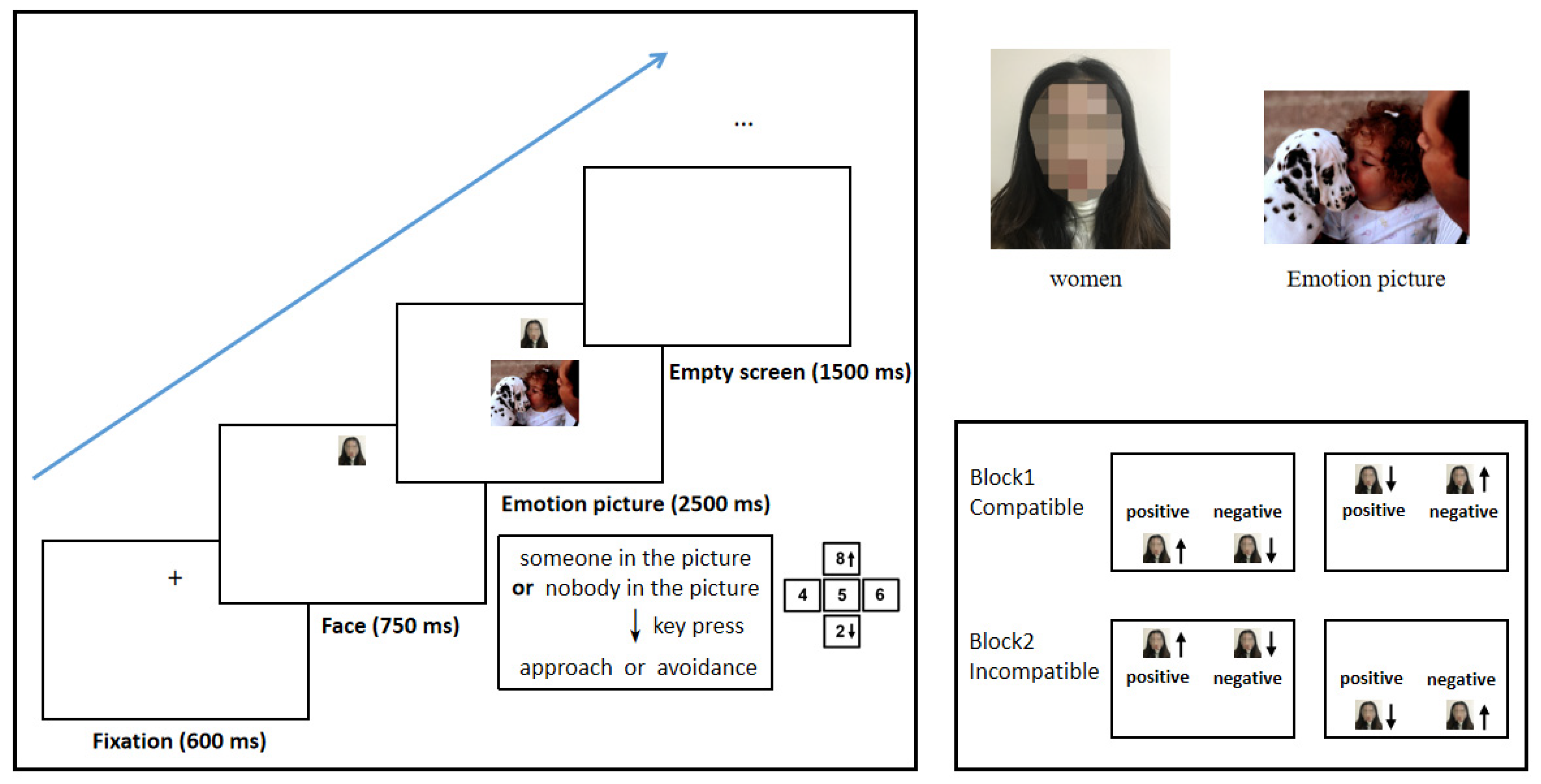

2.3.1. Experiment 1: Performance of the Compatible Effect of Approach–Avoidance in Women at Different Menstrual Cycle Phases during Conscious Processing

Materials

Procedure

2.3.2. Experiment 2: Performance of the Compatible Effect of Approach–Avoidance in Women at Different Menstrual Cycle Phases during Unconscious Processing

Materials

Procedure

2.4. Study Process

2.5. Hormonal Analyses of Saliva Samples

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subjective Measures

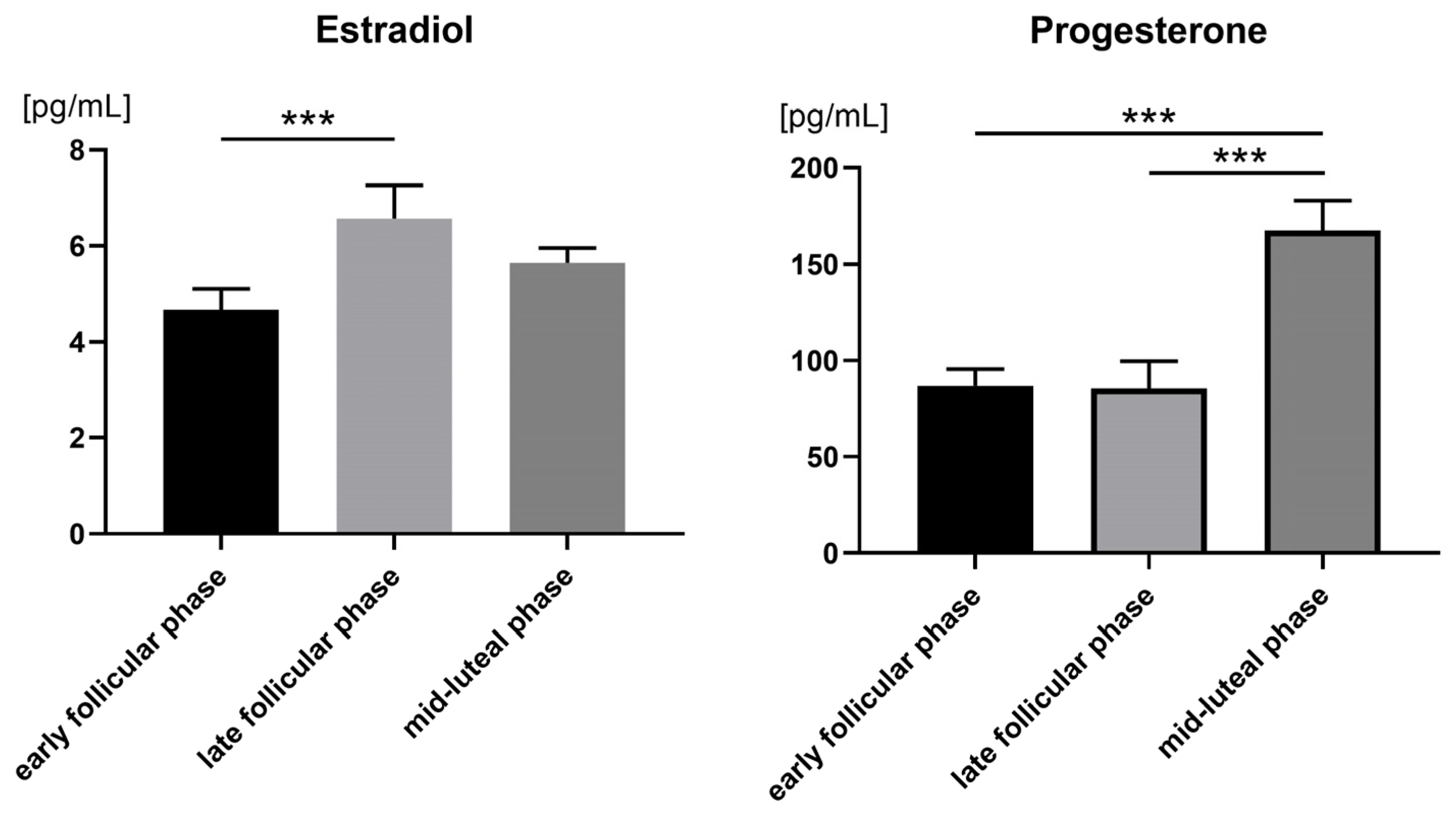

3.2. Hormone Levels

3.3. Performance

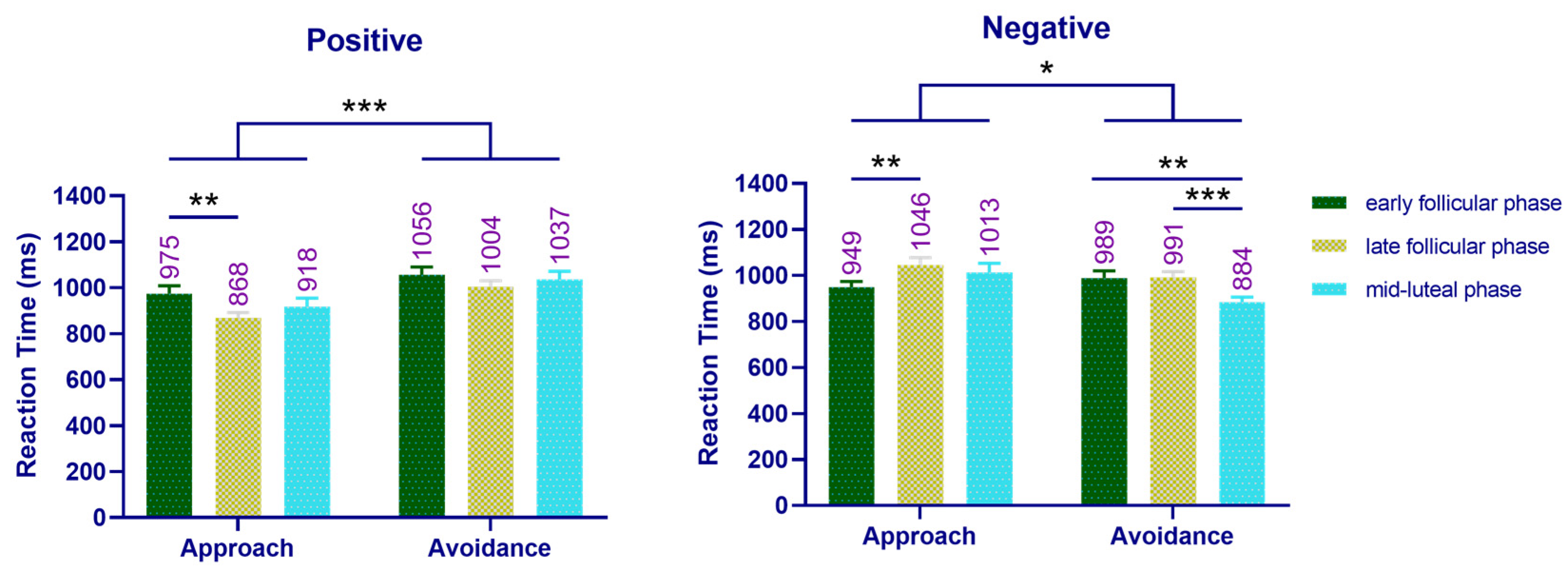

3.3.1. Reaction Times in Experiment 1

3.3.2. Correlation between Reaction Time and Sex Hormone Levels in Experiment 1

3.3.3. Response Times in Experiment 2

3.3.4. Correlation between Response Times and Sex Hormone Levels in Experiment 2

4. Discussion

4.1. The Approach–Avoidance Performance of Females in a Conscious/Unconscious State

4.2. Influence of the Menstrual Cycle on Approach–Avoidance Behavior of Women

4.2.1. Analysis of the Characteristics of Approach–Avoidance Behavior in Women in Late Follicular Phase

4.2.2. Relationship between Estradiol Levels and Benefit–Avoidance Behavior in Women in Late Follicular Phase

4.2.3. Analysis of Approach–Avoidance Behavior Characteristics in Women in Mid-Luteal Phase

4.2.4. Relationship between Progesterone Level and Approach–Avoidance Behavior in Women in Mid-Luteal Phase

4.3. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gray, J.A. Brain Systems that Mediate both Emotion and Cognition. Cogn. Emot. 1990, 4, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bargh, J.A. Consequences of Automatic Evaluation: Immediate Behavioral Predispositions to Approach or Avoid the Stimulus. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 25, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krieglmeyer, R.; Deutsch, R. Comparing measures of approach–avoidance behaviour: The manikin task vs. two versions of the joystick task. Cogn. Emot. 2010, 24, 810–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotteveel, M.; Phaf, R.H. Automatic affective evaluation does not automatically predispose for arm flexion and extension. Emotion 2004, 4, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelofs, K.; Minelli, A.; Mars, R.B.; van Peer, J.; Toni, I. On the neural control of social emotional behavior. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2009, 4, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eder, A.B.; Rothermund, K. When do motor behaviors (mis)match affective stimuli? An evaluative coding view of approach and avoidance reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2008, 137, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strack, F.; Deutsch, R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 8, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Xuan, Y.; Fu, X. The Effect of Emotional Valences on Approach and Avoidance Responses. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 20, 1023–1030. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, T.; Ric, F. The evaluation-behavior link: Direct and beyond valence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieglmeyer, R.; Deutsch, R.; De Houwer, J.; De Raedt, R. Being moved: Valence activates approach-avoidance behavior independently of evaluation and approach-avoidance intentions. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieglmeyer, R.; De Houwer, J.; Deutsch, R. How farsighted are behavioral tendencies of approach and avoidance? The effect of stimulus valence on immediate vs. ultimate distance change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xia, X.; Wang, D.; Song, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J. Involvement of the primary motor cortex in the early processing stage of the affective stimulus-response compatibility effect in a manikin task. Neuroimage 2021, 225, 117485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farage, M.A.; Osborn, T.W.; MacLean, A.B. Cognitive, sensory, and emotional changes associated with the menstrual cycle: A review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2008, 278, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.S.; Soares, C.N.; Poitras, J.R.; Prouty, J.; Alexander, A.B.; Shifren, J.L. Short-term use of estradiol for depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: A preliminary report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1519–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatzkin, R.R.; Morrow, A.L.; Light, K.C.; Pedersen, C.A.; Girdler, S.S. Associations of histories of depression and PMDD diagnosis with allopregnanolone concentrations following the oral administration of micronized progesterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 1208–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, T.; Rubenstein, B. The correlations between ovarian activity and psychodynamic processes. Psychosom. Med. 1939, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, J.C.; Schmidt, P.J.; Kohn, P.; Furman, D.; Rubinow, D.; Berman, K.F. Menstrual cycle phase modulates reward-related neural function in women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2465–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.; Chen, C.; Cheng, D.; Yang, S.; Huang, R.; Cacioppo, S.; Luo, Y.J. The mediation effect of menstrual phase on negative emotion processing: Evidence from N2. Soc. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, B.R.; Carr, A.R.; Ranson, V.A.; Felmingham, K.L. Women in the midluteal phase of the menstrual cycle have difficulty suppressing the processing of negative emotional stimuli: An event-related potential study. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 17, 886–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, C.A.; Jones, B.C.; DeBruine, L.M.; Welling, L.L.; Law Smith, M.J.; Perrett, D.I.; Sharp, M.A.; Al-Dujaili, E.A. Salience of emotional displays of danger and contagion in faces is enhanced when progesterone levels are raised. Horm. Behav. 2007, 51, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masataka, N.; Shibasaki, M. Premenstrual enhancement of snake detection in visual search in healthy women. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fessler, D.M. Luteal phase immunosuppression and meat eating. Riv. Biol. 2001, 94, 403–426. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R. Premenstrual Syndrome; Year Book Medical Publishers: Chicago, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine, L.M.; Jones, B.C.; Perrett, D.I. Women’s attractiveness judgments of self-resembling faces change across the menstrual cycle. Horm. Behav. 2005, 47, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangestad, S.W.; Thornhill, R. Menstrual cycle variation in women’s preferences for the scent of symmetrical men. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1998, 265, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haselton, M.G.; Gangestad, S.W. Conditional expression of women’s desires and men’s mate guarding across the ovulatory cycle. Horm. Behav. 2006, 49, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.C.; Little, A.C.; Boothroyd, L.; Debruine, L.M.; Feinberg, D.R.; Smith, M.J.; Cornwell, R.E.; Moore, F.R.; Perrett, D.I. Commitment to relationships and preferences for femininity and apparent health in faces are strongest on days of the menstrual cycle when progesterone level is high. Horm. Behav. 2005, 48, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.Y.; Wang, J.X. Women ornament themselves for intrasexual competition near ovulation, but for intersexual attraction in luteal phase. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarczyk, J.; Schwertner, E.; Wołoszyn, K.; Kuniecki, M. Phase of the menstrual cycle affects engagement of attention with emotional images. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 104, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Vagg, P.R. Psychometric properties of the STAI: A reply to Ramanaiah, Franzen, and Schill. J. Pers. Assess. 1984, 48, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, P.J.; Bradley, M.M.; Cuthbert, B.N. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Technical Manual and Affective Ratings. NIMH Cent. Study Emot. Atten. 1997, 1, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff, E.A.; Granger, D.A.; Schwartz, E.; Curran, M.J. Use of salivary biomarkers in biobehavioral research: Cotton-based sample collection methods can interfere with salivary immunoassay results. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001, 26, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.B. Direct effect of 17 beta-estradiol on striatum: Sex differences in dopamine release. Synapse 1990, 5, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Becker, J.B. Effects of estrogen agonists on amphetamine-stimulated striatal dopamine release. Synapse 1998, 29, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualini, C.; Olivier, V.; Guibert, B.; Frain, O.; Leviel, V. Acute stimulatory effect of estradiol on striatal dopamine synthesis. J. Neurochem. 1995, 65, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Sutton, S.K.; Scheier, M.F. Action, Emotion, and Personality: Emerging Conceptual Integration. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guapo, V.G.; Graeff, F.G.; Zani, A.C.; Labate, C.M.; dos Reis, R.M.; Del-Ben, C.M. Effects of sex hormonal levels and phases of the menstrual cycle in the processing of emotional faces. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.C.; Havlicek, J.; Flegr, J.; Hruskova, M.; Little, A.C.; Jones, B.C.; Perrett, D.I.; Petrie, M. Female facial attractiveness increases during the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2004, 271 (Suppl. S5), S270–S272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pipitone, R.N.; Gallup, G.G. Women’s voice attractiveness varies across the menstrual cycle. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2008, 29, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derntl, B.; Kryspin-Exner, I.; Fernbach, E.; Moser, E.; Habel, U. Emotion recognition accuracy in healthy young females is associated with cycle phase. Horm. Behav. 2008, 53, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, J.K.; Miller, S.L. Hormones and social monitoring: Menstrual cycle shifts in progesterone underlie women’s sensitivity to social information. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, D.S.; Fessler, D.M. Progesterone’s effects on the psychology of disease avoidance: Support for the compensatory behavioral prophylaxis hypothesis. Horm. Behav. 2011, 59, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.P.; Klein, S.L. Pregnancy and pregnancy-associated hormones alter immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Horm. Behav. 2012, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fessler, D.M.T.; Navarrete, C.D. Domain-specific variation in disgust sensitivity across the menstrual cycle. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2003, 24, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, S.M.; Sherman, P.W. Morning sickness: A mechanism for protecting mother and embryo. Q. Rev. Biol. 2000, 75, 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonia, A.; Nappi, R.E.; Pontillo, M.; Daverio, R.; Smeraldi, A.; Briganti, A.; Fabbri, F.; Zanni, G.; Rigatti, P.; Montorsi, F. Menstrual cycle-related changes in plasma oxytocin are relevant to normal sexual function in healthy women. Horm. Behav. 2005, 47, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X. The Effect of Menstrual Cycle Phases on Approach–Avoidance Behaviors in Women: Evidence from Conscious and Unconscious Processes. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101417

Li D, Zhang L, Wang X. The Effect of Menstrual Cycle Phases on Approach–Avoidance Behaviors in Women: Evidence from Conscious and Unconscious Processes. Brain Sciences. 2022; 12(10):1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101417

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Danyang, Lepu Zhang, and Xiaochun Wang. 2022. "The Effect of Menstrual Cycle Phases on Approach–Avoidance Behaviors in Women: Evidence from Conscious and Unconscious Processes" Brain Sciences 12, no. 10: 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101417

APA StyleLi, D., Zhang, L., & Wang, X. (2022). The Effect of Menstrual Cycle Phases on Approach–Avoidance Behaviors in Women: Evidence from Conscious and Unconscious Processes. Brain Sciences, 12(10), 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12101417