The Impact of Health and Social Services on the Quality of Life in Families of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Focus Group Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Focus Group

3.1.1. Well-Being

- Emotional Well-being

[…] We need to be considered as an endangered species, like pandas. We need to be protected. We need protection. When you start a new path, no one has to question it, it has to be supported, it cannot be uncertain so that I don’t know what happens tomorrow […] Because we families have invested in it, not only in economic terms, but also in terms of my own and my son’s life project.

[…] how many neuropsychiatrists have we changed in the last few years? Maybe three? […] and we are dealing with a service that should care for adults with disabilities. It is not possible to have to bear this discontinuity.

[Talking about school] […] we have changed two hundred million assistants, for one reason or another they disappeared.

- 2.

- Physical and Material Well-being

[Talking about behavioral educational interventions] For these things, we spend a lot of money, a lot of time, a lot of energy.

3.1.2. Independence

- Self-determination and Personal Development

[Talking about the parent’s self-organization in the Cooperative] There are so many who are looking at us with interest, hoping that we succeed because if it turns out that parents are able to self-organize, they can rely on us and help us in this empowerment process.

[Speaking about the Cooperative] What if this becomes a model that works. Small cafés can be installed in hotels, in small restaurants, in technical schools so that there can be people [with autism] who can be employed. They have fun with the carpentry workshops. Can you imagine how many situations you could create inside the neighbourhoods? However, this stuff works if it’s a widespread phenomenon.

3.1.3. Social Participation

- Interpersonal Relations

[…] We are demonstrating that when we act as a group, we are a cheerful company, we enjoy working together and we manage to build around us some consensus.

- 2.

- Social Inclusion

3.1.4. Rights

[Related to a sports program] He had to change his clothes between the bushes. Don’t make me say more….

[…] Do I have a right to ride the bus or not?

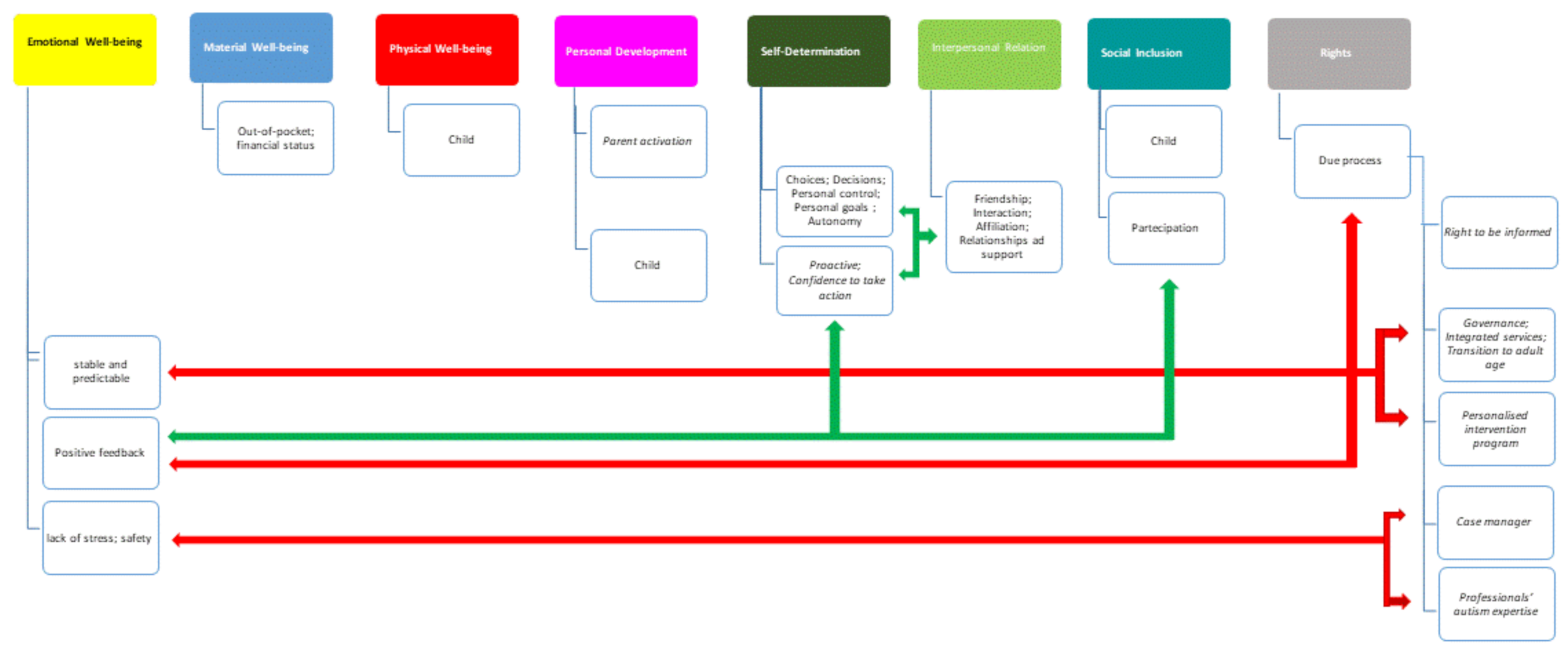

3.1.5. Linkages among QoL Domains

[…]We are here suffering, when no one is providing for our children, we try to fill the gap and create a stable care path for them.

[…]What is the result? That you as a family are alone in front of the institutions and therefore you succumb.

[Talking about the need of support by institution for parents’ self-initiatives]So I hope and dream of a time when the local health authorities present a call for children with autism to self-organize through cooperation.”

3.2. Service Survey Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scotish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 145 • Assessment, Diagnosis and Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders Key to Evidence Statements and Recommendations; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2016; pp. 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S. Achieving universal health coverage for mental disorders. BMJ 2019, 366, l4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hsiao, Y.J. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Family Demographics, Parental Stress, and Family Quality of Life. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 15, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, A.; Gigantesco, A.; Tarolla, E.; Stoppioni, V.; Cerbo, R.; Cremonte, M.; Alessandri, G.; Lega, I.; Nardocci, F. Parental Burden and its Correlates in Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Multicentre Study with Two Comparison Groups. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.; Lupfer, A.; Shattuck, P.T. Barriers to receipt of services for young adults with autism. Pediatrics 2018, 141, S300–S305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Anderson, C.; Butt, C. Young Adults on the Autism Spectrum: The Struggle for Appropriate Services. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3912–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik-Soni, N.; Shaker, A.; Luck, H.; Mullin, A.E.; Wiley, R.E.; Lewis, M.E.S.; Fuentes, J.; Frazier, T.W. Tackling healthcare access barriers for individuals with autism from diagnosis to adulthood. Pediatr. Res. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgi, M.; Ambrosio, V.; Cordella, D.; Chiarotti, F.; Venerosi, A. Nationwide Survey of Healthcare Services for Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Italy. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2019, 3, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cummins, R.A. Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, R.E.; Brown, I.E.; Nagler, M.E. Quality of Life in Health Promotion and Rehabilitation: Conceptual Approaches, Issues, and Applications; Sage Publications, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schalock, R.L.; Brown, I.; Brown, R.; Cummins, R.A.; Felce, D.; Matikka, L.; Keith, K.D.; Parmenter, T. Conceptualization, Measurement, and Application of Quality of Life for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities: Report of an International Panel of Experts. Ment. Retard. 2002, 40, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schalock, R.L.; Keith, K.D.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Gómez, L.E. Quality of Life Model Development and Use in the Field of Intellectual Disability; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N. The use of focus group methodology—With selected examples from sexual health research. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 29, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A.; Jenaro, C. Examining the factor structure and hierarchical nature of the quality of life construct. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 115, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, B.; Piller, A.; Giazzoni-Fialko, T.; Chainani, A. Meaningful outcomes for enhancing quality of life for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 42, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoresen, S.H.; Thomson, A.; Jackson, R.; Cocks, E. Meaningful social and economic inclusion through small business enterprise models of employment for adults with intellectual disability. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2018, 49, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, E.; Zonouzi, M. Re-Imagining Social Care Services in Co-Production with Disabled Parents 2018, University of Bedfordshire. Available online: https://www.drilluk.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Research-Findings-Munro-et-al.-2018 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Ferraro, M.; Trimarco, B.; Morganti, M.C.; Marino, G.; Pace, P.; Marino, L. Life-long individual planning in children with developmental disability: The active role of parents in the Italian experience. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Sanita 2020, 56, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A. A Conceptual and Measurement Framework to Guide Policy Development and Systems Change. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 9, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Brown, I. Quality of Life and Disability: An Approach for Community Practitioners; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Borgi, M.; Collacchi, B.; Correale, C.; Marcolin, M.; Tomasin, P.; Grizzo, A.; Orlich, R.; Cirulli, F. Social farming as an innovative approach to promote mental health, social inclusion and community engagement. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 2020, 56, 206–214. [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck, P.T.; Narendorf, S.C.; Cooper, B.; Sterzing, P.R.; Wagner, M.; Taylor, J.L. Postsecondary education and employment among youth with an autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laghi, F.; Trimarco, B. Individual planning starts at school. Tools and practices promoting autonomy and supporting transition to work for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 2020, 56, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Schall, C.M.; Wehman, P.; Brooke, V.; Graham, C.; McDonough, J.; Brooke, A.; Ham, W.; Rounds, R.; Lau, S.; Allen, J. Employment Interventions for Individuals with ASD: The Relative Efficacy of Supported Employment with or Without Prior Project SEARCH Training. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 3990–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruble, L.; McGrew, J.H.; Snell-Rood, C.; Adams, M.; Kleinert, H. Adapting COMPASS for Youth with ASD to Improve Transition Outcomes Using Implementation Science. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2018, 34, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.M.; Ellie Wilson, C.; Robertson, D.M.; Ecker, C.; Daly, E.M.; Hammond, N.; Galanopoulos, A.; Dud, L.; Murphy, D.G.; McAlonan, G.M. Autism spectrum disorder in adults: Diagnosis, management, and health services development. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burke, M.M.; Waitz-Kudla, S.N.; Rabideau, C.; Taylor, J.L.; Hodapp, R.M. Pulling back the curtain: Issues in conducting an intervention study with transition-aged youth with autism spectrum disorder and their families. Autism 2019, 23, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosnowy, C.; Silverman, C.; Shattuck, P. Parents’ and young adults’ perspectives on transition outcomes for young adults with autism. Autism 2018, 22, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, F.; Venerosi, A. A focus on the rights to self-determination and quality of life in people with mental disabilities. Editorial. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 2020, 56, 133–134. [Google Scholar]

- NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guidelines 4-Year Surveillance (2016). Autism in Adults (2012). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142/evidence/appendix-a-decision-matrix-pdf-2600145326 (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Simplican, S.C.; Leader, G.; Kosciulek, J.; Leahy, M. Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 38, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brix, J.; Krogstrup, H.K.; Mortensen, N.M. Evaluating the outcomes of co-production in local government. Local Gov. Stud. 2020, 46, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connolly, J.; Munro, A.; Mulherin, T.; MacGillivray, S.; Toma, M.; Gray, N.; Anderson, J. The leadership of co-production in health and social care integration in Scotland: A qualitative study. J. Soc. Policy 2021, in press. Available online: https://myresearchspace.uws.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/29239098/2021_09_27_Connolly_et_al_Leadership_accepted.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2021).

| Factor | Domain a | Indicators b |

|---|---|---|

| Well-being | Emotional well-being | Contentment, self-concept, lack of stress, safety, stable and predictable environments, positive feedback |

| Physical well-being | Health and health care, mobility, wellness, nutrition, activities of daily living, leisure | |

| Material well-being | Financial status/possessions, employment, ownership, housing | |

| Independence | Personal development | Education and habilitation, personal competence, performance, purposive activities, assistive technology |

| Self-determination | Autonomy/personal control, decisions, personal goals and values, choices | |

| Social participation | Interpersonal relations | Interactions, relationships and supports; affiliations, affection, intimacy, friendships |

| Social inclusion | Community integration and participation, community roles, social/natural supports, integrated environments | |

| Rights | Human (respect, dignity, equality) and legal (citizenship, access/barrier-free environments, due process, privacy, ownership) |

| Questions | % of Parents Agreeing with a Specific Option |

|---|---|

| What are the positive aspects of your Local Healthcare Authority? | 100% Few or none |

| What are the negative aspects of your Local Healthcare Authority? | 62.5% Extended waiting times; 75% Unclear communication; 87.5% Poor service offer; 75.0% Disorganization of the service; 62.5% Difficulty in accessing services; 75.0% Poor involvement and participation in decisions related to your child |

| What are the reasons for approaching your Local Healthcare Authority services? | 87.5% Certifications/bureaucratic issues |

| Which of your Local Healthcare Authority services would you like to see implemented/improved? | 62.5% Projects for independent living/cohousing/protected apartments; 75% Family support; 87.5% Job placement paths |

| Overall satisfaction for your experience with healthcare authority in the last 12 months (Likert 1–10 from ‘bad experience” to “great experience”) | 73% Low satisfaction |

| What are the reasons for approaching your Town Hall services? | 62.5% Recreational and sports projects and workshops |

| Overall satisfaction of your Town Hall authority (Likert 1–10 from “bad experience” to “great experience”) | 75% Low satisfaction |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correale, C.; Borgi, M.; Cirulli, F.; Laghi, F.; Trimarco, B.; Ferraro, M.; Venerosi, A. The Impact of Health and Social Services on the Quality of Life in Families of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Focus Group Study. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020177

Correale C, Borgi M, Cirulli F, Laghi F, Trimarco B, Ferraro M, Venerosi A. The Impact of Health and Social Services on the Quality of Life in Families of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Focus Group Study. Brain Sciences. 2022; 12(2):177. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020177

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorreale, Cinzia, Marta Borgi, Francesca Cirulli, Fiorenzo Laghi, Barbara Trimarco, Maurizio Ferraro, and Aldina Venerosi. 2022. "The Impact of Health and Social Services on the Quality of Life in Families of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Focus Group Study" Brain Sciences 12, no. 2: 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020177

APA StyleCorreale, C., Borgi, M., Cirulli, F., Laghi, F., Trimarco, B., Ferraro, M., & Venerosi, A. (2022). The Impact of Health and Social Services on the Quality of Life in Families of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Focus Group Study. Brain Sciences, 12(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020177