Abstract

Faces play a crucial role in social interactions. Developmental prosopagnosia (DP) refers to the lifelong difficulty in recognizing faces despite the absence of obvious signs of brain lesions. In recent decades, the neural substrate of this condition has been extensively investigated. While early neuroimaging studies did not reveal significant functional and structural abnormalities in the brains of individuals with developmental prosopagnosia (DPs), recent evidence identifies abnormalities at multiple levels within DPs’ face-processing networks. The current work aims to provide an overview of the convergent and contrasting findings by examining twenty-five years of neuroimaging literature on the anatomo-functional correlates of DP. We included 55 original papers, including 63 studies that compared the brain structure (MRI) and activity (fMRI, EEG, MEG) of healthy control participants and DPs. Despite variations in methods, procedures, outcomes, sample selection, and study design, this scoping review suggests that morphological, functional, and electrophysiological features characterize DPs’ brains, primarily within the ventral visual stream. Particularly, the functional and anatomical connectivity between the Fusiform Face Area and the other face-sensitive regions seems strongly impaired. The cognitive and clinical implications as well as the limitations of these findings are discussed in light of the available knowledge and challenges in the context of DP.

1. Introduction

Faces represent the stimuli we rely on the most for social interactions. They provide cues on others’ identity, age, gender, attractiveness, race, approachability, and emotions. Based on the evolutionary relevance of faces, most individuals can recognize others’ identities effortlessly thanks to dedicated face-selective cognitive mechanisms and the respective neural substrates [1]. In fact, unlike most everyday items, human faces are perceived as a whole, rather than assortments of features. According to the “domain-specific hypothesis” faces are processed holistically either due to an innate facial template [2] or because human faces represent the sole uniform stimuli for individual-level discrimination during the sensitive developmental period [3]. Alternatively, according to the “expertise hypothesis”, holistic processing results from automatized attention to whole objects, which is developed with extensive experience in discriminating them [4]. Despite the pivotal role of holistic processing, to date, the more consistent hypothesis (i.e., the “featural/configural hypothesis”) postulates that faces are processed by using both holistic (configural) and featural (i.e., analytic) mechanisms, emphasizing global characteristics (i.e., spatial relations) and specific face components (i.e., eyes, nose, and mouth), respectively [5,6,7]. Holistic and featural analyses of face stimuli can be used alternatively or together based on the task requests, stimulus presentation, and contextual demands [8,9].

The impairment of either or both of these mechanisms plays a role in a specific condition known as prosopagnosia [10], characterized by serious and (often) specific face identification deficits [11,12,13]. Albeit early scientific reports refer to the acquired form of prosopagnosia, where people lost their previously intact face recognition ability after a brain injury, research over the last ~25 years has increasingly focused on the developmental (or congenital) form of prosopagnosia (DP), which refers to the lifelong difficulty in recognizing faces despite the absence of brain damages [7,14,15,16].

Along with studies assessing the cognitive phenotype and interindividual variability of developmental prosopagnosia [14], much research has focused on the neural underpinnings of this condition [17]. This corpus of research is based on evidence from neurotypical individuals, showing the existence of face-sensitive neuro-cognitive mechanisms. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and invasive neuronal recordings in humans (and non-human primates) reveal the existence of a network of face-sensitive regions in the ventral occipito-temporal cortex (VOTC) [18,19,20,21,22]. Face-sensitive regions are mostly (albeit not specifically) right-lateralized and identified in the lateral surface of the inferior occipital cortex (i.e., occipital face area—OFA) [23], the lateral side of the fusiform gyrus (i.e., fusiform face area—FFA) [19], and the posterior part of the superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) [24].

Further neuroimaging evidence has unveiled two main face-sensitive networks in the human brain: (i) the core face network and (ii) the extended face network [21,25]. Following the early-stage analysis of face and structural processing in the OFA [26], information on invariant facial features (i.e., crucial information for face identity) reaches the FFA [21,27], while dynamic (changeable) features such as movements in eye gaze or facial expressions are directed to the pSTS [28,29,30]. Additional face-sensitive regions have also been described in the so-called extended face network. Indeed, the FFA projects to the anterior part of the medial (aMTG) and inferior temporal gyrus (aITG), which process the biographical and semantic information of known faces [31,32] (i.e., as suggested by patients with aTC damage causing the inability to access person-specific information from faces and names [33,34,35]). Further engaged areas include the intraparietal sulcus, which directs attention based on gaze; the auditory cortex, involved with speech perception; and the amygdala and limbic system, which process emotional information [20,21].

As for the temporal dynamics of face-processing, event-related potentials (ERPs) show that faces elicit specific occipito-temporal components [36]. A well-established ERP marker of face-sensitive cortical processing is the N170 [37,38,39], which consists of a large and often right-lateralized electroencephalography (EEG) deflection peaking between 150 and 200 ms over the occipitotemporal cortex in response to faces compared to non-face stimuli [40]. In magnetoencephalography (MEG), a similar component (i.e., the M170) is also observed [41,42,43,44]. Other components involved in face processing include the P1 (indexing a very early stage of face processing [45,46]), the N250 (reflecting the activation of preexisting and acquired face representations [47,48]), and the P600f (indexing later post-perceptual stages of face recognition [38,49]).

Albeit early neuroimaging—mainly single case—studies failed to show functional and morphological abnormalities in individuals with developmental prosopagnosia’s brains [50,51], recent evidence has shown face-network abnormalities at multiple levels [52,53]. This scoping review aims to shed light on convergent and contrasting findings, reviewing twenty-five years of neuroimaging literature on the anatomo-functional correlates of developmental prosopagnosia. Our objective is to map the functional and anatomical differences between individuals with developmental prosopagnosia and healthy controls to provide a starting point for future studies in this field.

2. Literature Search

Two researchers (AP and VM) conducted a literature search using PubMed (URL: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 7 May 2023) and Web of Science (URL: https://www.webofscience.com/, accessed on 7 May 2023) for reports published in the English language without time limits (last updated on 1 May 2023). The search keywords included (“developmental prosopagnosia” OR “congenital prosopagnosia”) AND (“magnetic resonance imaging” OR “diffusion tensor imaging” OR “electroencephalography” OR “magnetoencephalography” OR “positron emission tomography”). During the screening of publications, we also searched within their reference lists to identify additional eligible studies. Only original research comparing the brain structure and activity of healthy control participants (HC) and individuals with developmental prosopagnosia (DPs) were included in this review. In Table 1, the total number of records and studies included in this review are summarized based on technique and DPs sample size. The overall sample of DPs was 818, but many of them were involved in multiple studies. Due to the high heterogeneity in the methods, procedures, outcomes, sample selections, and study designs, we deliberately opted for a scoping review [54,55]. The methodologies, sample characteristics, and main results of the included studies are summarized in Table 2 (MRI studies) and Table 3 (EEG and MEG studies).

Table 1.

Outline of DP’s sample sizes per technique in the reviewed literature. The number of papers included in the review was 55, with 6 of them including 2 techniques for a total of 63 studies. Abbreviation: sMRI = structural MRI; DTI = diffusion tensor imaging; fc-fMRI = functional connectivity fMRI.

Table 2.

Magnetic resonance image studies comparing brain morphology, connectivity, and activity in developmental prosopagnosia participants (DPs) and healthy controls (HCs). Task abbreviations: FFT = Famous Face Test; CFMT = Cambridge Face Memory Test; CFPT = Cambridge Face Perception Test; BFRT = Benton Facial Recognition Test; WFMT = Warrington Face Memory Test; RMT = Recognition Memory Test; IQ = intelligence quotient.

Table 3.

EEG and MEG studies comparing brain activity in DPs and HCs. Abbreviations: FFT = Famous Face Test; CFMT = Cambridge Face Memory Test; CFPT = Cambridge Face Perception Test; BFRT = Benton Facial Recognition Test; WFMT = Warrington Face Memory Test; RMT = Recognition Memory Test; IQ = intelligence quotient.

3. The (In)visible Brain Markers of Developmental Prosopagnosia

3.1. Gray and White Matter Alterations

Contrary to the acquired form, a DP diagnosis requires face-processing difficulties to be present (presumably) since birth, not caused by any sign of a brain lesion, together with normal sensory and intellectual functions [103]. Nevertheless, differences in the cerebral architecture and connectivity have been reported in DP. Using various MRI techniques such as structural MRI, diffusor tensor imaging (DTI), and functional connectivity fMRI, researchers have been able to investigate the differences between DPs and HCs. This has allowed for an analysis of the links between structural and behavioral data.

Most of the reviewed studies reported a reduced density or volume in DPs’ temporal lobes compared to HCs, specifically in the pSTS, MTG, and FG (e.g., [21,25]). Such evidence was more consistent within the right hemisphere. As for white matter integrity, lower fractional anisotropy and functional connectivity were found in the core face network, particularly near the r-FFA (e.g., [53,75]). These findings are consistent with studies on the neural basis of face processing [104] and with injuries reported in acquired prosopagnosia [105,106]. On the other hand, the MTG and ITG are not face-selective regions; despite this, they are implicated in identifying and naming famous faces and buildings (i.e., semantic memory) [107].

Albeit DPs’ FFA and OFA gray matter volumes do not seem to be reduced, there is converging evidence about disrupted white matter within DPs’ VOTCs. Particularly, the r-OFA and r-FFA have emerged as central nodes where the connectivity within the core face network is compromised in DPs. Specifically, the r-OFA shows impairment in both the short-range and long-range functional connectivity within the core face network, whereas the r-FFA shows impairment mainly in the long-range functional connectivity and within the extended face network [52,53,79]. Further analyses revealed multiple regions in DPs’ core- and extended-face networks, whose functional connectivity to the r-OFA and r-FFA is decreased; such findings suggest the central role of the interaction between the r-FFA and the other regions of the core face network and the extended face network to successfully recognize faces.

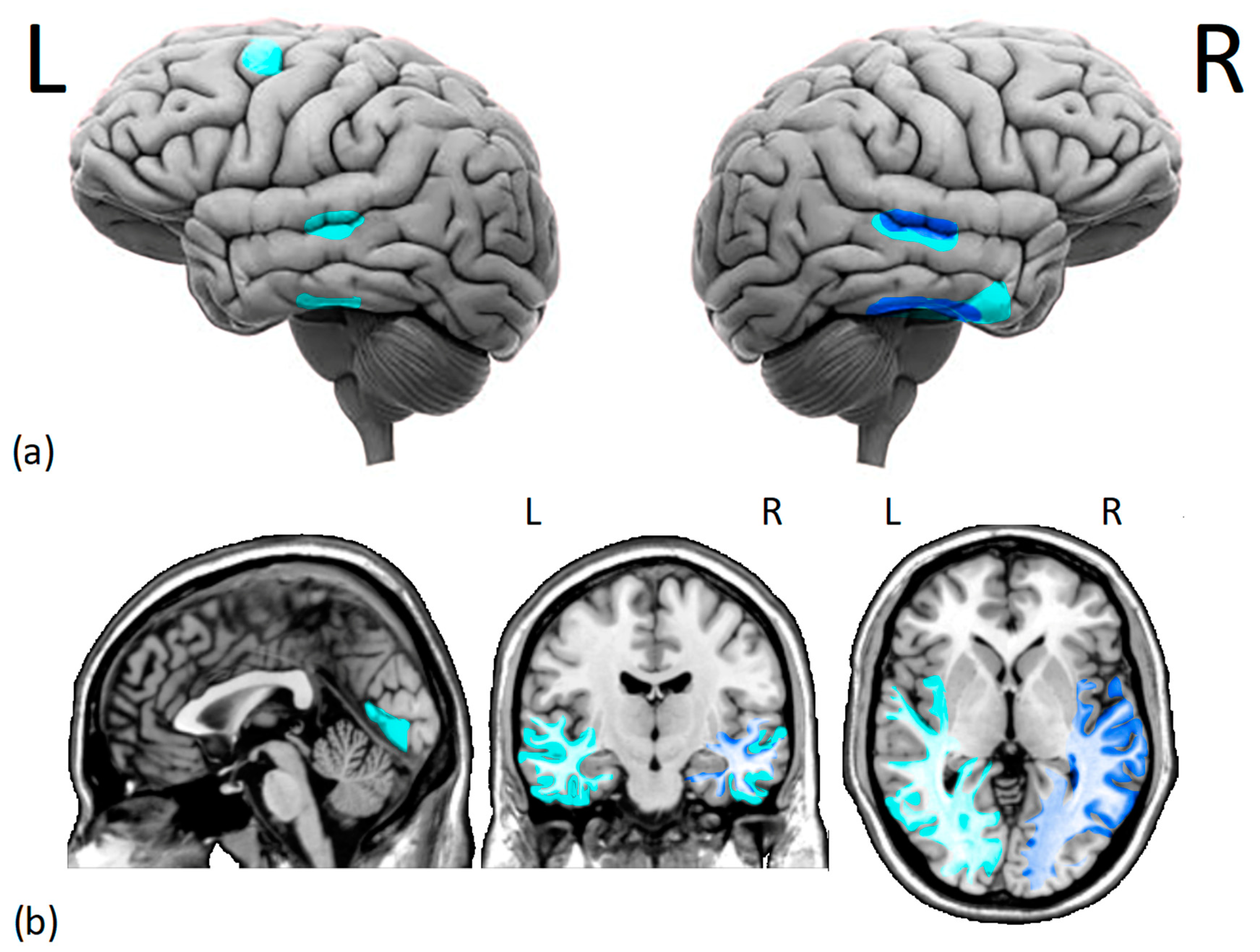

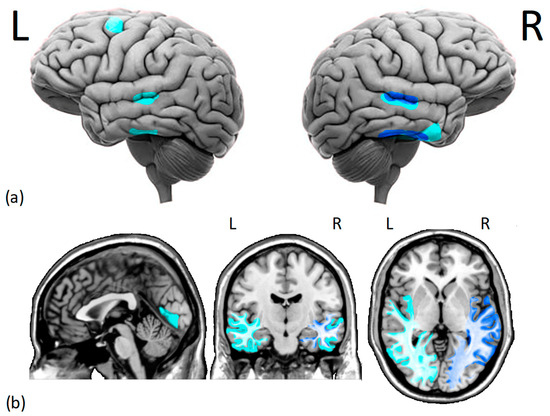

To summarize, despite the absence of a brain injury, gray matter alterations in the temporal lobe and white matter reductions involving the VOTC and aTC seem to characterize the DPs’ brains (see Figure 1). Reduced r-FFA’s white and gray matter volume and short-range functional connectivity would explain DPs’ face perception deficits, whereas disrupted functional connectivity between the r-FFA and r-pSTS and r-aTC seems to explain DPs’ deficits in face learning (i.e., memory) [53,73]. This hypothesis is in line with Garrido et al. [82] that the grey matter volume in the l-pSTS, aMTG, and r-FG (reduced in DPs compared with HCs) correlates with facial identity scores. Correlations between FFA structural deficits and behavioral measurements are observed mainly in the right hemisphere, where a dominance for face processing has been suggested by its larger size [19,108], higher probability of occurrence [109,110], and higher anatomical localization consistency of face-selective regions [111] compared to the left hemisphere.

Figure 1.

Cortical (a) and subcortical (b) issues in the gray and white matter of DPs brains. Several studies have found (i.e., dark blue) reduced morphometry measurements in the right fusiform face area and right superior temporal sulcus of DPs. Additionally, there is moderate evidence (i.e., light blue) of decreased gray matter density in the middle temporal gyrus, right anterior inferior temporal gyrus, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and lingual gyrus. Moreover, there is a reduction in white matter integrity and functional connectivity within the core face network and middle-anterior temporal cortex, especially on the right hemisphere. L = left hemisphere, R = right hemisphere.

Some results, however, do not support this conclusion. For instance, Haeger et al. and Gilaie-Dotan et al. [61,77] did not find any structural differences in DPs, while Behrmann et al. found larger MTGs in DPs [80]. Thomas et al. [52] reported a marked reduction in the structural integrity of two long white matter tracts in DPs, but subsequent studies have not confirmed or refined these results. Finally, a link between face memory impairments and decreased cortical density in the left lingual gyrus and l-DLPFC was found by Dinkelackler et al. [58]. Despite the role of these two regions in both visual cognition and memory processes, we point out that Dinkelackler’s DPs also showed mild impairments in non-face visual memory. Therefore, this finding cannot be attributed solely to deficits in facial memory but may reflect a more general visual impairment.

3.2. Face-Induced Brain Activity in Developmental Prosopagnosia

The studies investigating face-induced neural activity in DPs compared to HCs show different methodologies and findings (see fMRI studies in Table 2). The low temporal resolution of blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signals from fMRI, the advantage in terms on signal-to-noise ratio, and the technical limitations of performing tasks in the scanner determined a bias towards block designs compared to event-related designs. Indeed, most of the fMRI evidence for DP comes from block designs, particularly those adopting passive viewing and one-back tasks of faces vs. non-face stimuli. Although the former task is a perceptive task and the latter is a sequential face-discrimination task involving low memory load, they were both used to investigate the neural bases of face processing in DPs.

First, Jiahui et al. [63] investigated how selective attention to different aspects of faces affects brain activity in HCs and DPs; their results show that attention towards specific facial features (i.e., selective attention) modulates activity in both ventral areas (OFA and FFA) and dorsal areas (pSTS and inferior frontal gyrus): the modulation profiles in both pathways are similar between HCs and DPs, suggesting that DPs’ difficulties with recognizing faces are not due to attentional alterations, but rather due to face-specific perceptive or memory deficits. Accordingly, FFA activity when viewing faces correlates with individual differences in baseline face identification performances [59], and a lower FFA and OFA activity, mainly in the right hemisphere, was indeed observed in DPs during face viewing [66,67,69]. Moreover, DPs exhibited increased activity in the posterior visual regions and decreased connectivity between the occipital areas and the anterior temporal and frontal regions when viewing faces in comparison to HCs. These alterations correlate with face recognition scores and suggest the presence of peculiar network patterns in DPs [68].

To date, the model that best explains how face-relevant information flows through face-selective areas is based on the presence/absence of faces, which modulates the feed-forward effective connectivity from the primary and secondary visual cortices to the core face network. The connectivity within these networks during face viewing is significantly diminished in DPs relative to HCs, indicating that these connections may contribute to typical face-selective responses as well as accurate facial recognition [64]. Overall, these studies provide valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying face processing in DPs and highlight the prominent role of the FFA and its connections with other brain regions in face recognition.

Some researchers attempted to dissociate the neural activity related to face memory and perceptual processing; although DPs experience deficits in both face perception and face memory, there is a weak correlation between their performances in these tasks, indicating dissociable neural correlates. Compared to HCs, DPs show separate neural correlates for face memory and face perception within the core face network. Particularly, face memory is associated with activation in the bilateral FFA, while face perception is linked to face selectivity in the r-pSTS [72]. For instance, by adopting a modified Sternberg paradigm, Haeger et al. [77] investigated FFA activation patterns during face memory encoding and maintenance. An increased memory load entailed higher FFA activation and a higher degree of correlation between the activated voxels in HCs but not in DPs. Furthermore, the FFA activation patterns in the DPs were more unstable across the trials compared to the HCs. These findings suggest that DPs exhibit altered brain responses during the encoding and maintenance of face stimuli, which is linked to reduced performance in both long-term memory and mental imagery tasks with faces. Congruently, when learning of unfamiliar faces, DPs exhibit neural deficits characterized by diminished repetition suppression for faces in the FFA and decreased pattern stability for repeated faces in the bilateral MTG [71]. This indicates impairments in the perceptual analysis in the FFA and disrupted propagation from the FFA, which, along with deficits originating from the MTG itself, result in unstable mnemonic representations in the MTG. Notably, a significant correlation between memory task performance and pattern stability is found in the left MTG, but not the right MTG.

Other studies reported significant alterations beyond the VOTC. For instance, abnormalities in neural activity in response to familiar compared to unfamiliar faces in DPs exist in the left precuneus, anterior, and posterior cingulate cortex [76]. Furthermore, Rivolta et al. reported reduced face sensitivity in the aTC and reduced face–object discrimination in the right parahippocampal gyrus [69]. These regions are part of the extended face network and linked to post-perceptual face-processing stages, such as encoding or the retrieval of semantic and episodic memories about specific individuals [31]. Another study reported a reduced fMRI signal during face passive viewing in DPs’ LOCs, a region involved mainly in object visual processing [66], while Avidan et al. [51,56] failed to find any differences in brain activity between DPs and HCs during the passive viewing of faces and non-face stimuli.

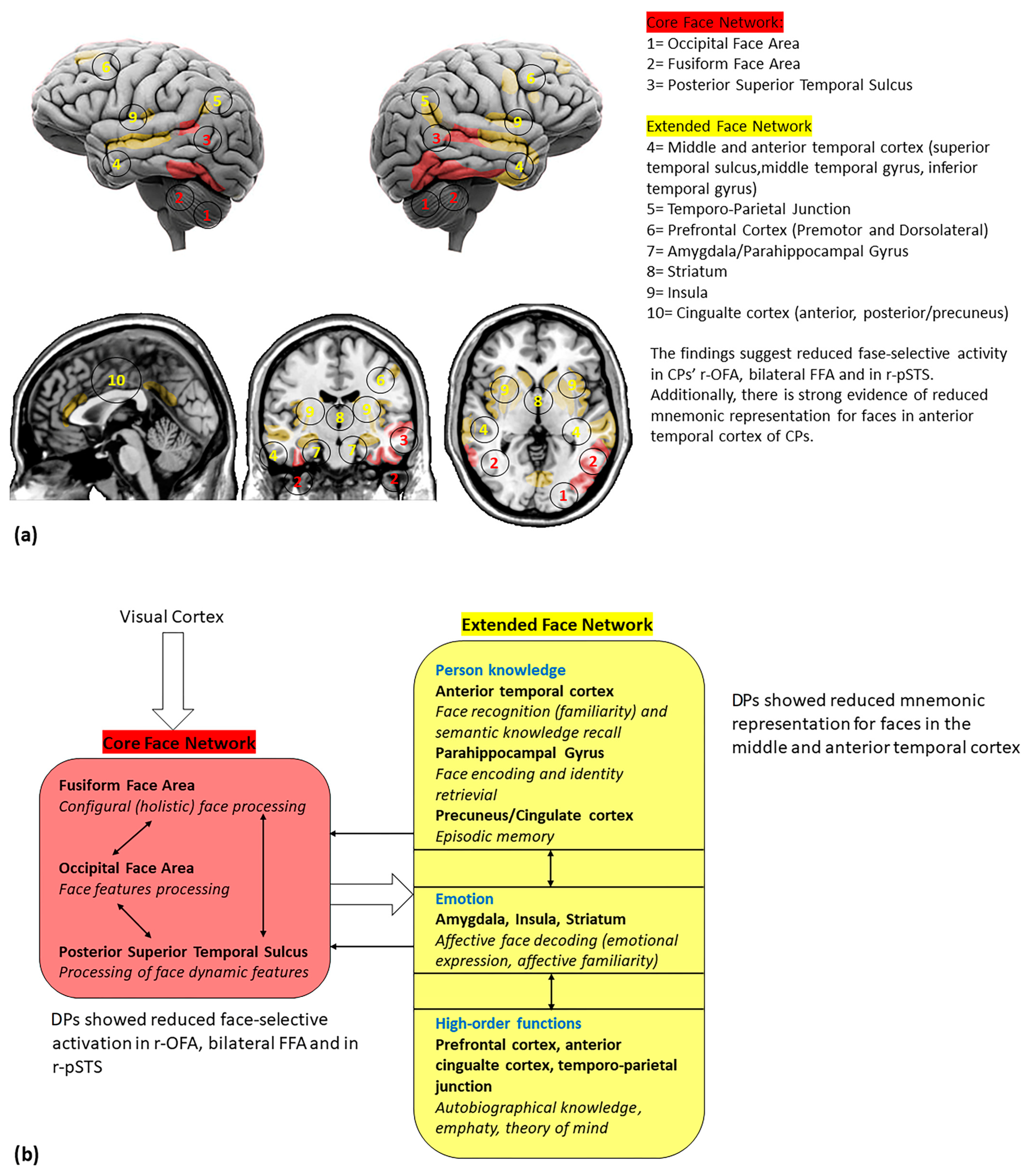

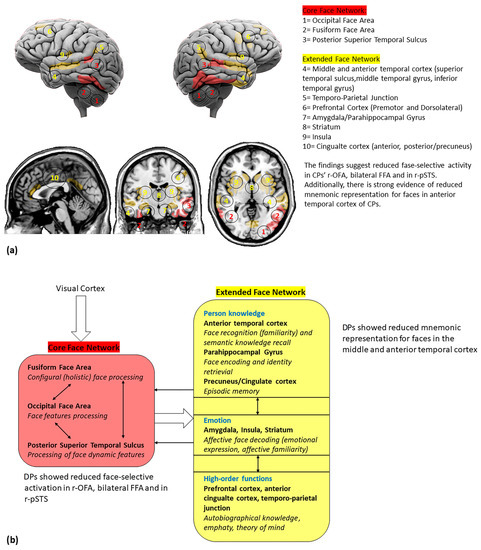

To sum up, the reviewed evidence suggests that DP is characterized by abnormal face representations that differ qualitatively from HCs. Indeed, DPs may rely on different aspects of facial features for successful face recognition (i.e., parts-based strategies) due to the FFA’s grey and white matter disruptions. Moreover, DPs who exhibit typical face perception performance show differential activation patterns compared to HCs, suggesting that some DPs develop compensation strategies. Overall, DPs exhibit abnormalities in neural face representation in both the FFA and r-OFA, indicating difficulties in both holistic and featural face processing (see Figure 2). The presence of both shared and specific neural correlates of face memory and face perception may help explain the heterogeneous nature of DPs and the related findings. However, several questions need to be addressed. First, while face perception is traditionally considered a preceding stage of face memory, the weak correlation between behavioral performances and the distinct core face network neural correlates of face perception and memory suggest that the former might be relatively independent of face memory. Secondly, deficit comorbidity in face memory and face perception in the extended face network is consistent with the hypothesis that the extended face network integrates information from the core face network. Future fMRI studies, using a simultaneous matching paradigm, should dissociate face perception and memory processes, investigating the role of these two cognitive domains in a developmental prosopagnosia deficit.

Figure 2.

(a) Cortical and subcortical brain regions involved in face perception; (b) a reviewed model of face networks, including the main findings from DPs studies. The white bold arrows indicate the links between different networks and the thin black arrows indicate the links between network hubs (adapted by Haxby et al. [21]).

4. EEG and MEG

The evidence from the EEG/MEG in DPs is summarized in Table 3. The functional impairment of the face-processing systems in DPs has been largely investigated via ERPs, which allow for examining real-time brain dynamics underlying face processing [36]. The N170—occurring around approximately 170 ms at the right lateral temporal electrode sites following the presentation of facial stimuli—represents a reliable marker of the early activation of facial representations [38,112], when features are perceptually “glued” into an indecomposable holistic whole [49,113].

Some ERP studies provide evidence for abnormal N170 responses in DPs. Since the first evidence from [81], the non-specificity of this component in DP has been reported in multiple studies showing that DPs exhibit same-amplitude N170 in response to faces and objects [50,61,84,87], as well as no typical N170 right laterality [86,98]. Larger-than-normal noise elicited from the N170 might account for the abovementioned non-selectivity of this component in DPs [90]. Indeed, early encoding processes reflected in the N170 might fail to discriminate between face and non-face stimuli in DPs [81,90]. As face identification relies on configural encoding, an impairment of this mechanism might be compensated by other general encoding strategies, resulting in poor face recognition and analogous electrophysiological responses to faces and non-face stimuli [84].

Evidence for reliable N170 amplitude differences between faces and nonface stimuli in DPs has also been reported [89]. It should be noted that neurophysiological discrepancies among studies might stem from differences in diagnostic criteria and participants’ characteristics (e.g., heterogeneous performances among DPs). This supports the idea that DP reflects a heterogonous impairment (i.e., with face-processing deficits being on a continuum) and that some behavioral deficits might not necessarily correlate with a lack of the face-selective N170 [114]. In addition to inter-individual differences, a compensatory mechanisms might be adopted by DPs to face perceptual processing deficits [89]. This implies the need for adopting multiple (e.g., both perceptual and mnemonic) and consistent measures of face processing across studies.

While face inversion in HCs leads to an enhanced and delayed N170 due to a loss of configural information [115,116], no such effect of upside-down faces is reported in DPs [91]. This could represent a functional deficit in configural face processing (i.e., less efficient use of prototypical spatial–configural information provided by upright faces). Indeed, DPs might prominently rely on feature-based strategies when processing faces [92]. In line with the idea of a reduced face-selectivity of visual areas in DPs, the paradoxical larger N170 for upright stimuli reported in some DPs might stem from the activation of object-sensitive areas in response to faces [91]. Interestingly, this abnormal inversion effect is reported with body stimuli, potentially due to the commonalities between face and body perception [65] and the almost equal relevance of configural mechanisms for body and face processing [117,118].

ERP evidence in DPs includes components such as the P1 (indexing a very early stage of face processing) [45,46], the N250 (reflecting the activation of preexisting and acquired face representations) [47,48], and the P600f (indexing later post-perceptual stages of face recognition) [38,49]. While evidence from the P1 component shows no inversion effect in DPs [92], N250 responses are reported for non-recognized faces in some DPs [95]. However, they seem to be attenuated, delayed, or qualitatively different in DPs compared to HCs [93,94,96]. These results suggest that stored visual representations of known faces might be available for DPs [119]. However, the activation of identity-specific visual memory traces could be inefficient in DPs and lead to covert face recognition. The absence of a P600f component for non-recognized famous faces coupled with reliable N250 indicates that some DPs might exhibit face recognition impairments at a later stage of face processing, potentially due to the disruption of links between stored visual representations of faces and semantic or episodic representations in long-term memory [95,120,121]. Furthermore, no P3 responses (i.e., reflecting advanced stages of face processing) are reported in DPs [98], suggesting that information for face representations could not be sufficiently attended to or deeply encoded. Despite the atypical patterns of visual scanning that cannot be excluded, these results provide support for the engagement of insufficient encoding resources and idiosyncratic cognitive strategies for face processing.

Further support for the abnormal electrophysiological responses in DP include the attenuated neural responses to unfamiliar faces in DPs compared to HCs (assessed via Fast Periodic Visual Stimulation EEG) [97], as well as abnormal and delayed EEG responses to faces (i.e., similar to those for processing non-face stimuli) [85]. This highlights the engagement of different cognitive processes during face recognition between DPs and HCs, with the former relying on a pathway more commonly associated with objects [85].

As compared to EEG, MEG provides good spatial resolution to investigate the neural sources of face-elicited responses [122]. Multiple studies have found a strong magnetic response (M170) to face stimuli compared with non-face stimuli over occipitotemporal brain regions in HCs [123]. The neural generators of the M170 are identified within the VOTC (e.g., [124]). Face-selective M170 patterns are reported in DPs, suggesting that impaired face recognition in developmental prosopagnosia is not necessarily characterized by an absence of face-specific responses [102]. Furthermore, in Rivolta et al. [100], DPs’ face-selective M170 in r-LOC correlates with configural face processing, whereas rFG-M170 correlates with featural processing. Importantly, M170 sensitivity correlates positively with face detection performances.

In addition to M170 abnormalities, some studies report alterations in brain activity in the ‘gamma’ frequency band (i.e., >30 Hz) in DPs [88,101,125]. This is in line with the literature highlighting the role of gamma-band oscillations at multiple stages of face perception [126,127,128] and the evidence for induced gamma-band responses as electrophysiological markers of face processing [99,129]. Again, the electrophysiological patterns of brain responses to faces in DPs, as well as the adopted cognitive strategies, might be qualitatively different across DPs and account for the literature inconsistencies. Indeed, genetically based prosopagnosia does not refer to a single trait, as it can encompass a cluster of subtypes (i.e., with patterns of impairments in specific components of the face-processing system) in individuals from the same family [130].

Despite DPs’ face perceptions being associated with both typical and atypical brain responses, the activity in face-sensitive areas seems to be altered in DPs compared to HCs, with (i) electrophysiological markers demonstrating the occurrence of overt face processing, (ii) differential activity patterns (e.g., laterality), and (iii) the activation of object-sensitive areas in response to faces, suggesting the adoption of insufficient or inadequate strategies. The main reliance on feature-based processing mechanisms and the lack of configural strategies seem to be consistent across studies. The literature inconsistencies might be related to differential participants’ selection procedures and adopted methods, which implies the need for defining more consistent diagnostic criteria for DP.

5. Literature Weakness

As reported in this review, different studies present sparse or contrasting findings. This divergence can be explained by several factors. First, the sample size in more than 35% of the reviewed literature accounts for five or fewer DPs (see Table 1), with most of them being single cases. Most DPs exhibit heterogeneity in their symptom manifestation and have been involved in multiple assessments using different techniques and procedures (e.g., [67,71] or [80,103]).

The selections of DPs represents a major issue in this field due to the lack of consensus on the exact diagnostic procedures and criteria [131]. Currently, researchers primarily rely on a limited set of neuropsychological tests investigating face processing. The most widely adopted are the Cambridge Face Memory Test [14], the famous faces test, and the Cambridge Face Perception Test [132]. However, arbitrary criteria are adopted to recruit DPs, and they vary among studies (e.g., in the adopted tests and versions and cut-off scores). In some studies, a diagnosis of DP is also provided to individuals exhibiting agnosia for objects other than faces, and comprehensive neuropsychological (e.g., including intelligence quotient) and vision disorder assessments are, in most cases, not provided [133]. We point out that standardizing the diagnostic criteria is crucial for the proper interpretation of the neuroimaging and neurophysiological findings.

Together with the intrinsic heterogeneity of DP, variations in the sample compositions and methods might have led to potential biases and could explain at least some of the inconsistencies. These methodological and procedural issues have been addressed in the recent literature with the adoption of larger samples and more rigorous protocols. For instance, most of the fMRI studies reviewed in this article used a block design instead of an event-related design, since the former provides a higher signal-to-noise ratio. Further, in recent years, fMRI protocols have embraced multivariate analyses (e.g., MVPA), which provide a more sensitive analytical approach than a traditional univariate analysis [134,135]. These studies have corroborated the involvement of the aTC in face processing and DP [69,70,71], a region known to be susceptible to fMRI signal distortion and drop-out [136,137].

6. Conclusions

DP is a neurodevelopmental disorder in which brain structural, functional, and electrophysiological alterations are observed. Consistent with the strong heritability of face recognition in the general population, DP has a genetic component (precisely, it may be a monogenic, autosomal dominant disorder) [132,138,139]. However, little is known about its onset, which is thought to be heterogeneous (i.e., of multiple etiologies). Similarly to other selective neurodevelopmental conditions, one hypothesis involves neural migration errors in the occipital and temporal regions during brain development [140,141]. This would also account for DP’s heterogeneity, based on how circumscribed these errors occur. However, given the lack of evidence, DP etiology represents a matter of debate [16].

The available MRI evidence highlights some recurring patterns in DP. Reduced gray matter volume is often observed in DPs’ temporal lobes, specifically in the pSTS, MTG, and FG. White matter alterations have been found in the core face network, particularly near the r-FFA. fMRI studies assessing brain activation in response to faces indicate that DPs exhibit lower activity in the right FFA and right OF, potentially due to disrupted feed-forward connectivity from the visual cortices to the core face network. The predominant right-lateralization of the impairments is in line with the evidence supporting the right hemisphere’s dominance in face processing [142]. Neural activation abnormalities in DP also extend beyond the VOTC to regions involved in post-perceptual face processing and object visual processing. Evidence from EEG/MEG studies reveal atypical N170 responses, with non-specificity and a lack of right laterality. Given the methodological and sample selection differences among the reviewed studies, the available findings are not fully consistent. Inter-individual variability among DP patients might also account for these inconsistencies and be linked to the DP heterogeneity.

Although most of the structural and functional impairments observed in DPs primarily involve the right hemisphere, the involvement of the left hemisphere regions is also common. Indeed, the neural face-processing network is distributed across both hemispheres, although a relative right-hemispheric dominance has been predominantly reported [143]. For example, Thome et al. [144] used fMRI to evaluate the cerebral face perception network in 108 healthy adults. While the average brain activity was higher in right-hemispheric areas than in left-hemispheric regions, this asymmetry was rather mild when compared to other lateralized brain functions such as language and spatial attention. This asymmetry differed greatly across individuals. The differences in lateralization between the core face network regions were not significant, and left-handed people did not display a general leftward shift in lateralization. However, when compared to right-handed men, left-handed men demonstrated a pronounced left-lateralization in the FFA. Another recent study [145], employing lateralized Rubin’s vase–faces figures, revealed that when the figure is presented in the left visual field (and processed by the right hemisphere), face perception (over vase) is more prevalent in males than in females. This difference is likely attributed to the stronger (right) hemispheric dominance observed in males compared with females when decoding face stimuli [146]. These findings highlight the heterogeneity in the individual patterns of hemisphere dominance for face perception and the importance of investigating the role of both hemispheres in DP.

These structural and functional alterations lead to face recognition and learning difficulties in DPs. To date, three main hypotheses have been proposed to explain the face-processing impairment in DPs: (i) the inefficient use of cognitive mechanisms devoted to face processing [147]; (ii) the impairment of within-class discrimination mechanisms that are not specific to faces [148,149]; and (iii) the reliance on different neurocognitive mechanisms to HCs, (i.e., with faces processed similarly to non-face stimuli) [150,151,152]. This latter hypothesis, which does not exclude an inefficient use of face-specific cognitive mechanisms, is extensively supported by the cognitive literature on DPs’ reliances on atypical aspects of facial features for successful face recognition [67]. This could reflect an adaptive mechanism in response to morphological and functional brain alterations.

The behavioral deficits in DPs have been strictly linked to the FFA white and grey matter abnormalities, as demonstrated by reduced face-selective activity in both the OFA and FFA. Indeed, although OFA gray matter seems not to be affected, the disrupted functional connectivity between the OFA and FFA could contribute to the normal reconstruction of individual facial features in a holistically integrated configuration, resulting in more feature-based processing [70,152,153]. Furthermore, the disrupted functional connectivity between the FFA and pSTS might contribute to the compromised static and dynamic integration of facial features.

At the behavioral level, not all DPs display reduced accuracy in face perception tasks, while face learning and memory are always impaired [154,155,156]. The use of inefficient face-processing strategies might interfere with the encoding of face identity as well as semantic and biographical information. EEG and MEG data provide support for this hypothesis.

Some relevant considerations can be drawn for future directions in this field. Future studies should select homogeneous samples of DPs based on an accurate assessment of their behavioral manifestations to account for disease heterogeneity. Different aspects of face processing (i.e., recognition, memory, discrimination) and face features (identity, expression, gaze) should be assessed simultaneously to uncover systematic associations and dissociations between different face deficits, which will unveil the varied behavioral profiles of face recognition deficits. In terms of interventional trajectories, the holistic face training developed by DeGutis et al. [157,158] was found to be effective in improving face identification, N170 face-selectivity, and functional connectivity between the r-FFA and r-OFA in DPs. These findings suggest that certain training regimes may improve face recognition ability in DPs. However, future studies should investigate therapeutic options in randomized controlled trials and assess the generalizability of training to daily life [16]. Indeed, the current literature lacks evidence on effective interventions to ameliorate DPs’ deficits. It would also be beneficial to develop a valid taxonomy of DP, which will help resolve inconsistent findings and facilitate research.

Author Contributions

V.M. and D.R. conceptualized the systematic revision; V.M. and A.P. performed the literature search; V.M., A.P. and M.V. wrote the draft; D.R. critically revised and supervised the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| DP | Developmental prosopagnosia |

| Sample | |

| HCs | Healthy control individuals |

| DPs | Individuals with developmental prosopagnosia |

| Neuroimage technique | |

| (f)MRI | (Functional) Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| MEG | Magnetoencephalography |

| ERP | Event-related potential |

| Brain region: | |

| VOTC | Ventral occipito-temporal cortex |

| FG | Fusiform gyrus |

| FFA | Fusiform face area |

| OFA | Occipital face area |

| ITG | Inferior temporal gyrus |

| MTG | Middle temporal gyrus |

| STS | Superior temporal sulcus |

| DLPFC | Dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex |

| LOC | Lateral occipital cortex |

| TC | Temporal cortex |

| p | posterior |

| a | anterior |

| r- | right |

| l- | left |

References

- Tsao, D.Y.; Livingstone, M.S. Mechanisms of Face Perception. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 31, 411–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J.; Johnson, M.H. CONSPEC and CONLERN: A Two-Process Theory of Infant Face Recognition. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKone, E.; Kanwisher, N.; Duchaine, B.C. Can Generic Expertise Explain Special Processing for Faces? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richler, J.J.; Wong, Y.K.; Gauthier, I. Perceptual Expertise as a Shift from Strategic Interference to Automatic Holistic Processing. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 20, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malatesta, G.; Manippa, V.; Tommasi, L. Crying the Blues: The Configural Processing of Infant Face Emotions and Its Association with Postural Biases. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2022, 84, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossion, B. Picture-Plane Inversion Leads to Qualitative Changes of Face Perception. Acta Psychol. 2008, 128, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, M.; Brkić, D.; Pizzamiglio, S.; Premoli, I.; Rivolta, D. Neurophysiological Correlates of Featural and Spacing Processing for Face and Non-Face Stimuli. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Palmisano, A.; Innamorato, F.; Tedesco, G.; Manippa, V.; Caffò, A.O.; Rivolta, D. Face Memory and Facial Expression Recognition Are Both Affected by Wearing Disposable Surgical Face Masks. Cogn. Process 2023, 24, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Innamorato, F.; Palmisano, A.; Cicinelli, G.; Nobile, E.; Manippa, V.; Keller, R.; Rivolta, D. Investigating the Impact of Disposable Surgical Face-Masks on Face Identity and Emotion Recognition in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodamer, J. Die Prosop-Agnosie: Die Agnosie Des Physiognomieerkennens. Arch. Für Psychiatr. Nervenkrankh. 1947, 179, 6–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A.R.; Damasio, H.; Van Hoesen, G.W. Prosopagnosia: Anatomic Basis and Behavioral Mechanisms. Neurology 1982, 32, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossion, B. Distinguishing the Cause and Consequence of Face Inversion: The Perceptual Field Hypothesis. Acta Psychol. 2009, 132, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivolta, D.; Lawson, R.P.; Palermo, R. More than Just a Problem with Faces: Altered Body Perception in a Group of Congenital Prosopagnosics. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2017, 70, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchaine, B.C.; Nakayama, K. Developmental Prosopagnosia: A Window to Content-Specific Face Processing. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006, 16, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, C.; Sozzi, M.; Bossi, F.; Corbo, M.; Rivolta, D. Atypical Holistic Processing of Facial Identity and Expression in a Case of Acquired Prosopagnosia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2019, 36, 358–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilo, T.; Duchaine, B. Advances in Developmental Prosopagnosia Research. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2013, 23, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, T.; Grüter, M.; Carbon, C.-C. Neural and Genetic Foundations of Face Recognition and Prosopagnosia. J. Neuropsychol. 2008, 2, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrett, D.I.; Rolls, E.T.; Caan, W. Visual Neurones Responsive to Faces in the Monkey Temporal Cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 1982, 47, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwisher, N.; McDermott, J.; Chun, M.M. The Fusiform Face Area: A Module in Human Extrastriate Cortex Specialized for Face Perception. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 4302–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxby, J.V.; Gobbini, M.I. Distributed Neural Systems for Face Perception. In The Oxford Handbook of Face Perception; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Haxby, J.V.; Hoffman, E.A.; Gobbini, M.I. The Distributed Human Neural System for Face Perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, E.M.; Borzello, M.; Freiwald, W.A.; Tsao, D. Intelligent Information Loss: The Coding of Facial Identity, Head Pose, and Non-Face Information in the Macaque Face Patch System. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 7069–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, D.; Walsh, V.; Duchaine, B. The Role of the Occipital Face Area in the Cortical Face Perception Network. Exp. Brain Res. 2011, 209, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, M.; Yovel, G. Two Neural Pathways of Face Processing: A Critical Evaluation of Current Models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 55, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haxby, J.V.; Hoffman, E.A.; Gobbini, M.I. Human Neural Systems for Face Recognition and Social Communication. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 51, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitcher, D.; Walsh, V.; Yovel, G.; Duchaine, B. TMS Evidence for the Involvement of the Right Occipital Face Area in Early Face Processing. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1568–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, T.J.; Ewbank, M.P. Distinct Representations for Facial Identity and Changeable Aspects of Faces in the Human Temporal Lobe. Neuroimage 2004, 23, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, C.P.; Moore, C.D.; Engell, A.D.; Todorov, A.; Haxby, J.V. Distributed Representations of Dynamic Facial Expressions in the Superior Temporal Sulcus. J. Vis. 2010, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovel, G.; O’Toole, A.J. Recognizing People in Motion. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazard, A.; Schiltz, C.; Rossion, B. Recovery from Adaptation to Facial Identity Is Larger for Upright than Inverted Faces in the Human Occipito-Temporal Cortex. Neuropsychologia 2006, 44, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbini, M.I.; Haxby, J.V. Neural Systems for Recognition of Familiar Faces. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveroni, C.L.; Seidenberg, M.; Mayer, A.R.; Mead, L.A.; Binder, J.R.; Rao, S.M. Neural Systems Underlying the Recognition of Familiar and Newly Learned Faces. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghesani, V.; Narvid, J.; Battistella, G.; Shwe, W.; Watson, C.; Binney, R.J.; Sturm, V.; Miller, Z.; Mandelli, M.L.; Miller, B. “Looks Familiar, but I Do Not Know Who She Is”: The Role of the Anterior Right Temporal Lobe in Famous Face Recognition. Cortex 2019, 115, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainotti, G. Face Familiarity Feelings, the Right Temporal Lobe and the Possible Underlying Neural Mechanisms. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 56, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainotti, G. Different Patterns of Famous People Recognition Disorders in Patients with Right and Left Anterior Temporal Lesions: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Russo, F.; Berchicci, M.; Bianco, V.; Perri, R.L.; Pitzalis, S.; Quinzi, F.; Spinelli, D. Normative Event-Related Potentials from Sensory and Cognitive Tasks Reveal Occipital and Frontal Activities Prior and Following Visual Events. Neuroimage 2019, 196, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentin, S.; Allison, T.; Puce, A.; Perez, E.; McCarthy, G. Electrophysiological Studies of Face Perception in Humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1996, 8, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, A.; Eimer, M. An Event-Related Brain Potential Study of Explicit Face Recognition. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 2736–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, M.; Negrini, M.; Nitsche, M.A.; Rivolta, D. Anodal-tDCS over the Human Right Occipital Cortex Enhances the Perception and Memory of Both Faces and Objects. Neuropsychologia 2016, 81, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towler, J.; Eimer, M. Electrophysiological Studies of Face Processing in Developmental Prosopagnosia: Neuropsychological and Neurodevelopmental Perspectives. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2012, 29, 503–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Cassidy, A.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Rimm, E.B.; Ascherio, A. Habitual Intake of Dietary Flavonoids and Risk of Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2012, 78, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Miki, K.; Kakigi, R. Mechanisms of Face Perception in Humans: A Magneto-and Electro-Encephalographic Study. Neuropathology 2005, 25, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borra, D.; Bossi, F.; Rivolta, D.; Magosso, E. Deep Learning Applied to EEG Source-Data Reveals Both Ventral and Dorsal Visual Stream Involvement in Holistic Processing of Social Stimuli. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivolta, D.; Castellanos, N.P.; Stawowsky, C.; Helbling, S.; Wibral, M.; Grützner, C.; Koethe, D.; Birkner, K.; Kranaster, L.; Enning, F. Source-Reconstruction of Event-Related Fields Reveals Hyperfunction and Hypofunction of Cortical Circuits in Antipsychotic-Naive, First-Episode Schizophrenia Patients during Mooney Face Processing. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 5909–5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.J. Non-Spatial Attentional Effects on P1. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 1903–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itier, R.J.; Taylor, M.J. Face Recognition Memory and Configural Processing: A Developmental ERP Study Using Upright, Inverted, and Contrast-Reversed Faces. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, J.M.; Schweinberger, S.R.; Burton, A.M. N250 ERP Correlates of the Acquisition of Face Representations across Different Images. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2009, 21, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, J.W.; Curran, T.; Porterfield, A.L.; Collins, D. Activation of Preexisting and Acquired Face Representations: The N250 Event-Related Potential as an Index of Face Familiarity. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2006, 18, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimer, M. Event-Related Brain Potentials Distinguish Processing Stages Involved in Face Perception and Recognition. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2000, 111, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, U.; Avidan, G.; Deouell, L.Y.; Bentin, S.; Malach, R. Face-Selective Activation in a Congenital Prosopagnosic Subject. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidan, G.; Hasson, U.; Malach, R.; Behrmann, M. Detailed Exploration of Face-Related Processing in Congenital Prosopagnosia: 2. Functional Neuroimaging Findings. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2005, 17, 1150–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Avidan, G.; Humphreys, K.; Jung, K.; Gao, F.; Behrmann, M. Reduced Structural Connectivity in Ventral Visual Cortex in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. The Neural Network for Face Recognition: Insights from an fMRI Study on Developmental Prosopagnosia. Neuroimage 2018, 169, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avidan, G.; Tanzer, M.; Hadj-Bouziane, F.; Liu, N.; Ungerleider, L.G.; Behrmann, M. Selective Dissociation between Core and Extended Regions of the Face Processing Network in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Cereb. Cortex 2014, 24, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGutis, J.M.; Bentin, S.; Robertson, L.C.; D’Esposito, M. Functional Plasticity in Ventral Temporal Cortex Following Cognitive Rehabilitation of a Congenital Prosopagnosic. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 1790–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkelacker, V.; Grüter, M.; Klaver, P.; Grüter, T.; Specht, K.; Weis, S.; Kennerknecht, I.; Elger, C.E.; Fernandez, G. Congenital Prosopagnosia: Multistage Anatomical and Functional Deficits in Face Processing Circuitry. J. Neurol. 2011, 258, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furl, N.; Garrido, L.; Dolan, R.J.; Driver, J.; Duchaine, B. Fusiform Gyrus Face Selectivity Relates to Individual Differences in Facial Recognition Ability. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 1723–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Klargaard, S.K.; Alnæs, D.; Kolskår, K.K.; Karstoft, J.; Westlye, L.T.; Starrfelt, R. Left Hemisphere Abnormalities in Developmental Prosopagnosia When Looking at Faces but Not Words. Brain Commun. 2019, 1, fcz034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilaie-Dotan, S.; Perry, A.; Bonneh, Y.; Malach, R.; Bentin, S. Seeing with Profoundly Deactivated Mid-Level Visual Areas: Non-Hierarchical Functioning in the Human Visual Cortex. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjikhani, N.; de Gelder, B. Neural Basis of Prosopagnosia: An fMRI Study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002, 16, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiahui, G.; Yang, H.; Duchaine, B. Attentional Modulation Differentially Affects Ventral and Dorsal Face Areas in Both Normal Participants and Developmental Prosopagnosics. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2020, 37, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, M.; Garrido, L.; Driver, J.; Dolan, R.J.; Duchaine, B.C.; Furl, N. Effective Connectivity from Early Visual Cortex to Posterior Occipitotemporal Face Areas Supports Face Selectivity and Predicts Developmental Prosopagnosia. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 3821–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnebusch, D.A.; Daum, I. Neuropsychological Mechanisms of Visual Face and Body Perception. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2009, 33, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, K.; Zimmer, M.; Nagy, K.; Bankó, É.M.; Vidnyanszky, Z.; Vakli, P.; Kovács, G. Altered Bold Response Within the Core Face-Processing Network in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Ideggyógyászati Szle. 2015, 68, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. Multi-Item Discriminability Pattern to Faces in Developmental Prosopagnosia Reveals Distinct Mechanisms of Face Processing. Cereb. Cortex 2020, 30, 2986–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, G.; Tanzer, M.; Simony, E.; Hasson, U.; Behrmann, M.; Avidan, G. Altered Topology of Neural Circuits in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Elife 2017, 6, e25069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, D.; Woolgar, A.; Palermo, R.; Butko, M.; Schmalzl, L.; Williams, M.A. Multi-Voxel Pattern Analysis (MVPA) Reveals Abnormal fMRI Activity in Both the “Core” and “Extended” Face Network in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y. Neural Decoding Reveals Impaired Face Configural Processing in the Right Fusiform Face Area of Individuals with Developmental Prosopagnosia. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tian, F.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. Multiple-Stage Impairments of Unfamiliar Face Learning in Developmental Prosopagnosia: Evidence from fMRI Repetition Suppression and Multi-Voxel Pattern Stability. Neuropsychologia 2022, 176, 108370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, J. Separate and Shared Neural Basis of Face Memory and Face Perception in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 668174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, J.; Pestilli, F.; Witthoft, N.; Golarai, G.; Liberman, A.; Poltoratski, S.; Yoon, J.; Grill-Spector, K. Functionally Defined White Matter Reveals Segregated Pathways in Human Ventral Temporal Cortex Associated with Category-Specific Processing. Neuron 2015, 85, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, D.; Soricelli, A.; Ponari, M.; Salvatore, E.; Quarantelli, M.; Prinster, A.; Trojano, L. Structural Connectivity in a Single Case of Progressive Prosopagnosia: The Role of the Right Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus. Cortex 2014, 56, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Garrido, L.; Nagy, Z.; Mohammadi, S.; Steel, A.; Driver, J.; Dolan, R.J.; Duchaine, B.; Furl, N. Local but Not Long-Range Microstructural Differences of the Ventral Temporal Cortex in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 2015, 78, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avidan, G.; Behrmann, M. Functional MRI Reveals Compromised Neural Integrity of the Face Processing Network in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1146–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeger, A.; Pouzat, C.; Luecken, V.; N’diaye, K.; Elger, C.; Kennerknecht, I.; Axmacher, N.; Dinkelacker, V. Face Processing in Developmental Prosopagnosia: Altered Neural Representations in the Fusiform Face Area. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 744466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Stock, J.; van de Riet, W.A.; Righart, R.; de Gelder, B. Neural Correlates of Perceiving Emotional Faces and Bodies in Developmental Prosopagnosia: An Event-Related fMRI-Study. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J. Altered Spontaneous Neural Activity in the Occipital Face Area Reflects Behavioral Deficits in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 2016, 89, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrmann, M.; Avidan, G.; Gao, F.; Black, S. Structural Imaging Reveals Anatomical Alterations in Inferotemporal Cortex in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 2354–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentin, S.; Deouell, L.Y.; Soroker, N. Selective Visual Streaming in Face Recognition: Evidence from Developmental Prosopagnosia. Neuroreport 1999, 10, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, L.; Furl, N.; Draganski, B.; Weiskopf, N.; Stevens, J.; Tan, G.C.-Y.; Driver, J.; Dolan, R.J.; Duchaine, B. Voxel-Based Morphometry Reveals Reduced Grey Matter Volume in the Temporal Cortex of Developmental Prosopagnosics. Brain 2009, 132, 3443–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Stock, J.; Vandenbulcke, M.; Zhu, Q.; Hadjikhani, N.; De Gelder, B. Developmental Prosopagnosia in a Patient with Hypoplasia of the Vermis Cerebelli. Neurology 2012, 78, 1700–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentin, S.; DeGutis, J.M.; D’Esposito, M.; Robertson, L.C. Too Many Trees to See the Forest: Performance, Event-Related Potential, and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Manifestations of Integrative Congenital Prosopagnosia. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.J.; Tree, J.J.; Weidemann, C.T. Recognition Memory in Developmental Prosopagnosia: Electrophysiological Evidence for Abnormal Routes to Face Recognition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E.; Dundas, E.; Gabay, Y.; Plaut, D.C.; Behrmann, M. Hemispheric Organization in Disorders of Development. Vis. Cogn. 2017, 25, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kress, T.; Daum, I. Event-Related Potentials Reflect Impaired Face Recognition in Patients with Congenital Prosopagnosia. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 352, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueschow, A.; Weber, J.E.; Carbon, C.-C.; Deffke, I.; Sander, T.; Grüter, T.; Grüter, M.; Trahms, L.; Curio, G. The 170ms Response to Faces as Measured by MEG (M170) Is Consistently Altered in Congenital Prosopagnosia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnebusch, D.A.; Suchan, B.; Ramon, M.; Daum, I. Event-Related Potentials Reflect Heterogeneity of Developmental Prosopagnosia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 2234–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, K.; Zimmer, M.; Schweinberger, S.R.; Vakli, P.; Kovács, G. The Background of Reduced Face Specificity of N170 in Congenital Prosopagnosia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towler, J.; Gosling, A.; Duchaine, B.; Eimer, M. The Face-Sensitive N170 Component in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 3588–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righart, R.; de Gelder, B. Impaired Face and Body Perception in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 17234–17238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K.; Towler, J.; Eimer, M. Face Identity Matching Is Selectively Impaired in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Cortex 2017, 89, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towler, J.; Fisher, K.; Eimer, M. Holistic Face Perception Is Impaired in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Cortex 2018, 108, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eimer, M.; Gosling, A.; Duchaine, B. Electrophysiological Markers of Covert Face Recognition in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Brain 2012, 135, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parketny, J.; Towler, J.; Eimer, M. The Activation of Visual Face Memory and Explicit Face Recognition Are Delayed in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Neuropsychologia 2015, 75, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.; Towler, J.; Rossion, B.; Eimer, M. Neural Responses in a Fast Periodic Visual Stimulation Paradigm Reveal Domain-General Visual Discrimination Deficits in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Cortex 2020, 133, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares, E.I.; Urraca, A.S.; Lage-Castellanos, A.; Iglesias, J. Different and Common Brain Signals of Altered Neurocognitive Mechanisms for Unfamiliar Face Processing in Acquired and Developmental Prosopagnosia. Cortex 2021, 134, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobel, C.; Junghöfer, M.; Gruber, T. The Role of Gamma-Band Activity in the Representation of Faces: Reduced Activity in the Fusiform Face Area in Congenital Prosopagnosia. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, D.; Palermo, R.; Schmalzl, L.; Williams, M.A. Investigating the Features of the M170 in Congenital Prosopagnosia. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobel, C.; Putsche, C.; Zwitserlood, P.; Junghöfer, M. Early Left-Hemispheric Dysfunction of Face Processing in Congenital Prosopagnosia: An MEG Study. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.M.; Duchaine, B.C.; Nakayama, K. Normal and Abnormal Face Selectivity of the M170 Response in Developmental Prosopagnosics. Neuropsychologia 2005, 43, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrmann, M.; Avidan, G. Congenital Prosopagnosia: Face-Blind from Birth. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, C.J.; Iaria, G.; Barton, J.J. Defining the Face Processing Network: Optimization of the Functional Localizer in fMRI. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009, 30, 1637–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.J. Structure and Function in Acquired Prosopagnosia: Lessons from a Series of 10 Patients with Brain Damage. J. Neuropsychol. 2008, 2, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorger, B.; Goebel, R.; Schiltz, C.; Rossion, B. Understanding the Functional Neuroanatomy of Acquired Prosopagnosia. Neuroimage 2007, 35, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Chao, L.L. Semantic Memory and the Brain: Structure and Processes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001, 11, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yovel, G.; Tambini, A.; Brandman, T. The Asymmetry of the Fusiform Face Area Is a Stable Individual Characteristic That Underlies the Left-Visual-Field Superiority for Faces. Neuropsychologia 2008, 46, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peelen, M.V.; Downing, P.E. Within-Subject Reproducibility of Category-Specific Visual Activation with Functional MRI. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2005, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, K.S.; Grill-Spector, K. Sparsely-Distributed Organization of Face and Limb Activations in Human Ventral Temporal Cortex. Neuroimage 2010, 52, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, K.S.; Golarai, G.; Caspers, J.; Chuapoco, M.R.; Mohlberg, H.; Zilles, K.; Amunts, K.; Grill-Spector, K. The Mid-Fusiform Sulcus: A Landmark Identifying Both Cytoarchitectonic and Functional Divisions of Human Ventral Temporal Cortex. Neuroimage 2014, 84, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossion, B.; Jacques, C. Does Physical Interstimulus Variance Account for Early Electrophysiological Face Sensitive Responses in the Human Brain? Ten Lessons on the N170. Neuroimage 2008, 39, 1959–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagiv, N.; Bentin, S. Structural Encoding of Human and Schematic Faces: Holistic and Part-Based Processes. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2001, 13, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Grand, R.; Cooper, P.A.; Mondloch, C.J.; Lewis, T.L.; Sagiv, N.; de Gelder, B.; Maurer, D. What Aspects of Face Processing Are Impaired in Developmental Prosopagnosia? Brain Cogn. 2006, 61, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossion, B.; Delvenne, J.-F.; Debatisse, D.; Goffaux, V.; Bruyer, R.; Crommelinck, M.; Guérit, J.-M. Spatio-Temporal Localization of the Face Inversion Effect: An Event-Related Potentials Study. Biol. Psychol. 1999, 50, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossion, B.; Gauthier, I.; Tarr, M.J.; Despland, P.; Bruyer, R.; Linotte, S.; Crommelinck, M. The N170 Occipito-Temporal Component Is Delayed and Enhanced to Inverted Faces but Not to Inverted Objects: An Electrophysiological Account of Face-Specific Processes in the Human Brain. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonemei, R.; Costantino, A.I.; Battistel, I.; Rivolta, D. The Perception of (Naked Only) Bodies and Faceless Heads Relies on Holistic Processing: Evidence from the Inversion Effect. Br. J. Psychol. 2018, 109, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviezer, H.; Trope, Y.; Todorov, A. Holistic Person Processing: Faces with Bodies Tell the Whole Story. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, D.; Palermo, R.; Schmalzl, L.; Coltheart, M. Covert Face Recognition in Congenital Prosopagnosia: A Group Study. Cortex 2012, 48, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, N.; Caine, D.; Coltheart, M.; Hendy, J.; Roberts, C. Towards an Understanding of Delusions of Misidentification: Four Case Studies. Mind Lang. 2000, 15, 74–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, V.; Young, A. Understanding Face Recognition. Br. J. Psychol. 1986, 77, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivolta, D.; Palermo, R.; Schmalzl, L.; Williams, M.A. An Early Category-Specific Neural Response for the Perception of Both Places and Faces. Cogn. Neurosci. 2012, 3, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Higuchi, M.; Marantz, A.; Kanwisher, N. The Selectivity of the Occipitotemporal M170 for Faces. Neuroreport 2000, 11, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deffke, I.; Sander, T.; Heidenreich, J.; Sommer, W.; Curio, G.; Trahms, L.; Lueschow, A. MEG/EEG Sources of the 170-Ms Response to Faces Are Co-Localized in the Fusiform Gyrus. Neuroimage 2007, 35, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.; Trujillo-Barreto, N.J.; Giabbiconi, C.-M.; Valdés-Sosa, P.A.; Müller, M.M. Brain Electrical Tomography (BET) Analysis of Induced Gamma Band Responses during a Simple Object Recognition Task. NeuroImage 2006, 29, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, M.; Wakui, E.; Thoma, V.; Nitsche, M.A.; Rivolta, D. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) at 40 Hz Enhances Face and Object Perception. Neuropsychologia 2019, 135, 107237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmisano, A.; Chiarantoni, G.; Bossi, F.; Conti, A.; D’Elia, V.; Tagliente, S.; Nitsche, M.A.; Rivolta, D. Face Pareidolia Is Enhanced by 40 Hz Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) of the Face Perception Network. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion-Golumbic, E.; Golan, T.; Anaki, D.; Bentin, S. Human Face Preference in Gamma-Frequency EEG Activity. Neuroimage 2008, 39, 1980–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon-Baudry, C.; Bertrand, O. Oscillatory Gamma Activity in Humans and Its Role in Object Representation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalzl, L.; Palermo, R.; Coltheart, M. Cognitive Heterogeneity in Genetically Based Prosopagnosia: A Family Study. J. Neuropsychol. 2008, 2, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.J.S.; Corrow, S.L. The Problem of Being Bad at Faces. Neuropsychologia 2016, 89, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchaine, B.; Germine, L.; Nakayama, K. Family Resemblance: Ten Family Members with Prosopagnosia and within-Class Object Agnosia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2007, 24, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geskin, J.; Behrmann, M. Congenital Prosopagnosia without Object Agnosia? A Literature Review. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2018, 35, 4–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, J.-D.; Rees, G. Decoding Mental States from Brain Activity in Humans. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.A.; Polyn, S.M.; Detre, G.J.; Haxby, J.V. Beyond Mind-Reading: Multi-Voxel Pattern Analysis of fMRI Data. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006, 10, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur, M.; Bandettini, P.A.; Kriegeskorte, N. Revealing Representational Content with Pattern-Information fMRI—An Introductory Guide. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2009, 4, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojemann, J.G.; Akbudak, E.; Snyder, A.Z.; McKinstry, R.C.; Raichle, M.E.; Conturo, T.E. Anatomic Localization and Quantitative Analysis of Gradient Refocused Echo-Planar fMRI Susceptibility Artifacts. NeuroImage 1997, 6, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennerknecht, I.; Ho, N.Y.; Wong, V.C.N. Prevalence of Hereditary Prosopagnosia (HPA) in Hong Kong Chinese Population. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2008, 146A, 2863–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennerknecht, I.; Grueter, T.; Welling, B.; Wentzek, S.; Horst, J.; Edwards, S.; Grueter, M. First Report of Prevalence of Non-Syndromic Hereditary Prosopagnosia (HPA). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2006, 140, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchaine, B.C.; Yovel, G.; Butterworth, E.J.; Nakayama, K. Prosopagnosia as an Impairment to Face-Specific Mechanisms: Elimination of the Alternative Hypotheses in a Developmental Case. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2006, 23, 714–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, F. Neurobiology of Dyslexia: A Reinterpretation of the Data. Trends Neurosci. 2004, 27, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossion, B.; Caldara, R.; Seghier, M.; Schuller, A.-M.; Lazeyras, F.; Mayer, E. A Network of Occipito-Temporal Face-Sensitive Areas besides the Right Middle Fusiform Gyrus Is Necessary for Normal Face Processing. Brain 2003, 126, 2381–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossion, B.; Lochy, A. Is Human Face Recognition Lateralized to the Right Hemisphere Due to Neural Competition with Left-Lateralized Visual Word Recognition? A Critical Review. Brain Struct. Funct. 2022, 227, 599–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, I.; García Alanis, J.C.; Volk, J.; Vogelbacher, C.; Steinsträter, O.; Jansen, A. Let’s Face It: The Lateralization of the Face Perception Network as Measured with fMRI Is Not Clearly Right Dominant. NeuroImage 2022, 263, 119587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brancucci, A.; Ferracci, S.; D’Anselmo, A.; Manippa, V. Hemispheric Functional Asymmetries and Sex Effects in Visual Bistable Perception. Conscious. Cogn. 2023, 113, 103551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proverbio, A.M.; Brignone, V.; Matarazzo, S.; Del Zotto, M.; Zani, A. Gender Differences in Hemispheric Asymmetry for Face Processing. BMC Neurosci. 2006, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.; Duchaine, B.; Nakayama, K. Super-Recognizers: People with Extraordinary Face Recognition Ability. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2009, 16, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.J.; Arnold, T.; Bukach, C.M. P-Curving the Fusiform Face Area: Meta-Analyses Support the Expertise Hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 104, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGugin, R.W.; Gauthier, I. Perceptual Expertise with Objects Predicts Another Hallmark of Face Perception. J. Vis. 2009, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bobak, A.K.; Bennetts, R.J.; Parris, B.A.; Jansari, A.; Bate, S. An In-Depth Cognitive Examination of Individuals with Superior Face Recognition Skills. Cortex 2016, 82, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobak, A.K.; Parris, B.A.; Gregory, N.J.; Bennetts, R.J.; Bate, S. Eye-Movement Strategies in Developmental Prosopagnosia and “Super” Face Recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2017, 70, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGutis, J.; Cohan, S.; Mercado, R.J.; Wilmer, J.; Nakayama, K. Holistic Processing of the Mouth but Not the Eyes in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2012, 29, 419–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGutis, J.; Chatterjee, G.; Mercado, R.J.; Nakayama, K. Face Gender Recognition in Developmental Prosopagnosia: Evidence for Holistic Processing and Use of Configural Information. Vis. Cogn. 2012, 20, 1242–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, K.A.; Garrido, L.; Duchaine, B. Dissociation between Face Perception and Face Memory in Adults, but Not Children, with Developmental Prosopagnosia. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2014, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, P.I.; Wilkinson, D.T.; Ferguson, H.J.; Smith, L.J.; Bindemann, M.; Johnston, R.A.; Schmalzl, L. Perceptual and Memorial Contributions to Developmental Prosopagnosia. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2017, 70, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKone, E.; Hall, A.; Pidcock, M.; Palermo, R.; Wilkinson, R.B.; Rivolta, D.; Yovel, G.; Davis, J.M.; O’Connor, K.B. Face Ethnicity and Measurement Reliability Affect Face Recognition Performance in Developmental Prosopagnosia: Evidence from the Cambridge Face Memory Test–Australian. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2011, 28, 109–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGutis, J.M.; Chiu, C.; Grosso, M.E.; Cohan, S. Face Processing Improvements in Prosopagnosia: Successes and Failures over the Last 50 Years. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGutis, J.; Cohan, S.; Nakayama, K. Holistic Face Training Enhances Face Processing in Developmental Prosopagnosia. Brain 2014, 137, 1781–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).