Neurocognitive Psychiatric and Neuropsychological Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic and Clinical Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Motor parkinsonian symptoms begin to appear when striatal dopamine levels are reduced between 70% and 80% of normal levels, which approximately corresponds to a loss of 50% of the total synapses of the substantia nigra towards the striatum, which is the central nucleus of input of motor information from the cortex towards the basal nuclei, fed back by nigrostriatal pathways to modulate movement through motor anagrams (chunks of motion information) stored in the basal ganglia.

- This threshold is directly related to the appearance of symptoms: there is a correlation between the extent of damage to the dopaminergic system and the severity of the symptoms because neuronal destruction gradually produces a progressive deficit of dopamine in the striatum, which induces a significant loss of voluntary or involuntary spontaneous movement.

- Destruction of the striatal dopaminergic pathway and blocking of striatal dopamine receptors cause motor deficits similar to those observed in PD, both in humans and experimental animals induced with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OH-DA), reserpine, or methamphetamine.

- Drug therapies that cause an increase in dopamine availability or stimulate dopamine receptors at the level of the striatum reduce the symptoms associated with this deficit, mainly motor ones [4].

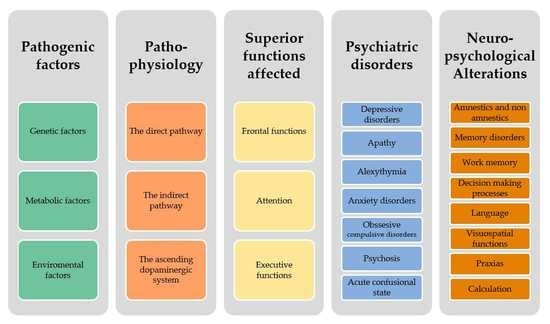

2. Pathogenic Factors

- Genetic factors: The onset of disease before age 40 indicates a parkinsonian syndrome of genetic origin, the most typical representative of which is the autosomal recessive mutation of Parkin (PARK2). Monogenic families represent less than 5%. More than 15 genetic mutations have been reported with autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance. However, family history comes into play, even in monogenic cases, as the risk of PD is 6.7 times higher for siblings and 3.2 times for children of patients with PD [22].

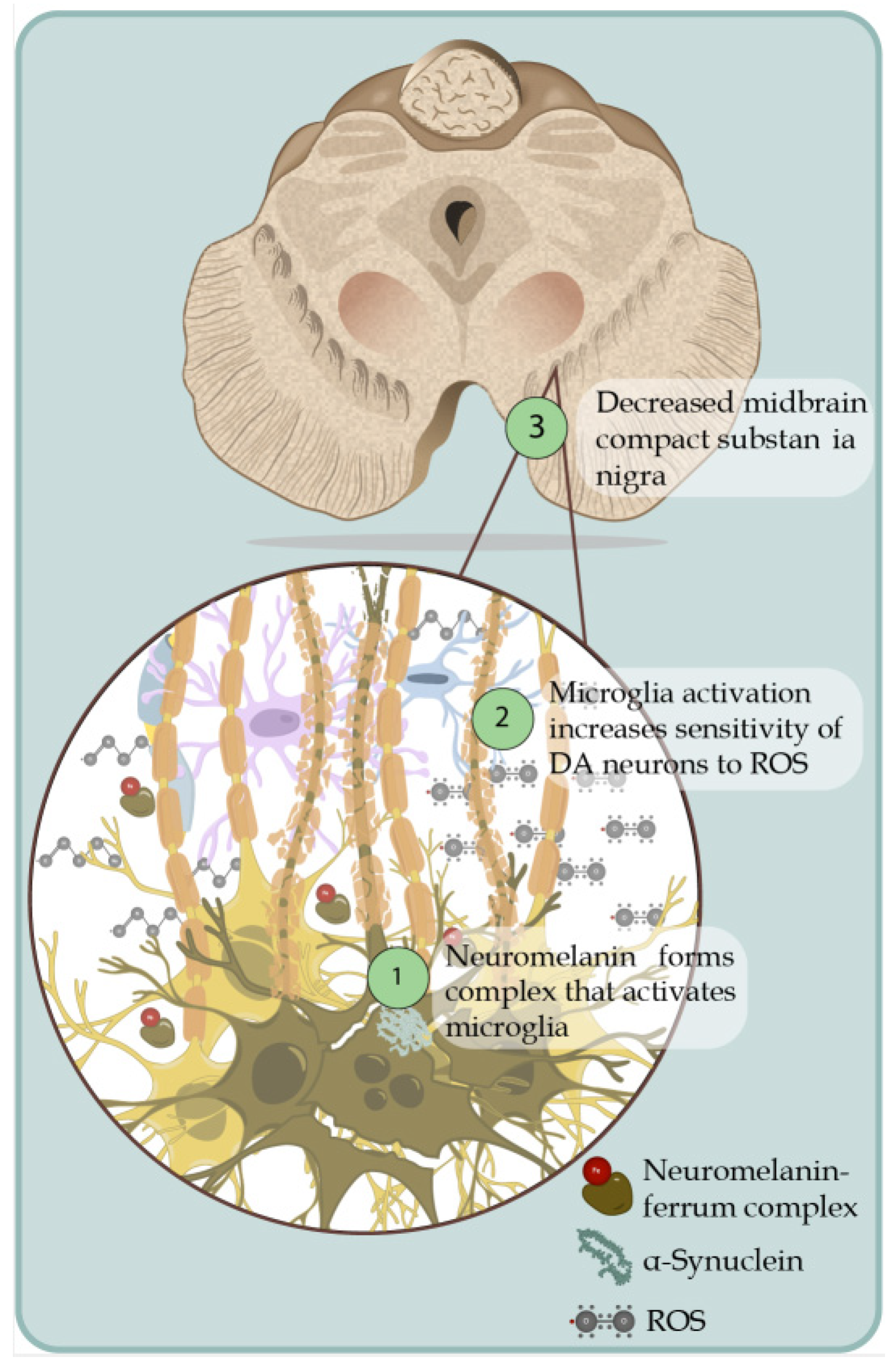

- Metabolic factors: Metabolic alterations leading to chronic oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and abnormal endo- and exotoxin elimination mechanisms are postulated.

- Environmental factors: Exposure to certain environmental toxins such as heavy metals (mainly manganese but also copper, lead, or iron), welding (or work with the use of welding material), insecticides, herbicides, and others represent epidemiologically proven risk factors.

3. Pathophysiology of Neuropsychiatric Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease

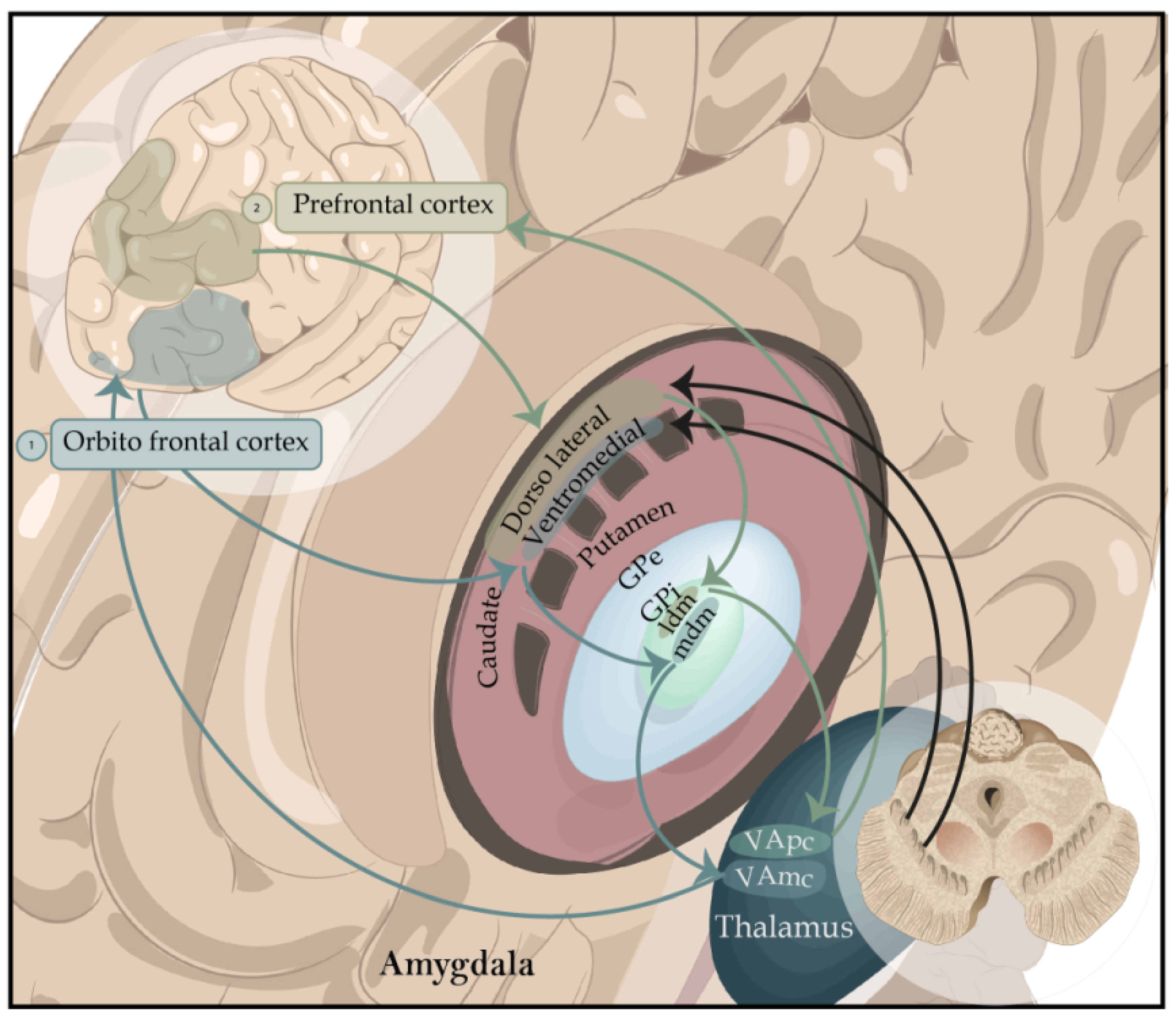

- The direct pathway (dorsal striatum/internal segment of the globus pallidus/pars reticulata of the substantia nigra/thalamus/premotor cortex/orbitofrontal cortex) exerts a facilitating action of movement.

- The activity of the indirect pathway (dorsal striatum/external segment of the globus pallidus/internal segment of the globus pallidus/pars reticulata of the substantia nigra/thalamus/premotor cortex/orbitofrontal cortex) has a modulatory inhibition of the action of rival movements to the specific tasks the basal ganglia have chosen to do [28]. Therefore, the deficit of cognitive functions based on the prefrontal cortex, defined globally as an executive deficit (attention, executive roles, working memory), which characterizes many patients with PD from the early stages of the disease, does not derive so much from a direct pathology of the prefrontal cortex as from the reduction in dopaminergic stimulation at the striatal level, which prevents the normal functioning of the frontostriatal circuits. Recent neuroanatomical studies suggest that the evolutionary profile of executive deficit in PD follows the spatiotemporal progression of dopamine reduction at the striatal level concerning the different frontostriatal connections [29]. In the early stages of the disease, dopamine depletion occurs mainly in the dorsolateral portion of the caudate nucleus, an area connected to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [30], and, thus, affects the dorsolateral frontostriatal circuit [26]. Therefore, in the initial stages of the disease, the executive functions based on this dorsolateral circuit will be deficient, while the executive functions based on the orbital circuit, not yet affected by the dopaminergic reduction, will be mostly intact. The different levels of dopaminergic reduction between the dorsolateral and the orbital circuits and the distinction between direct and indirect pathways within each frontostriatal circuit are of particular importance.

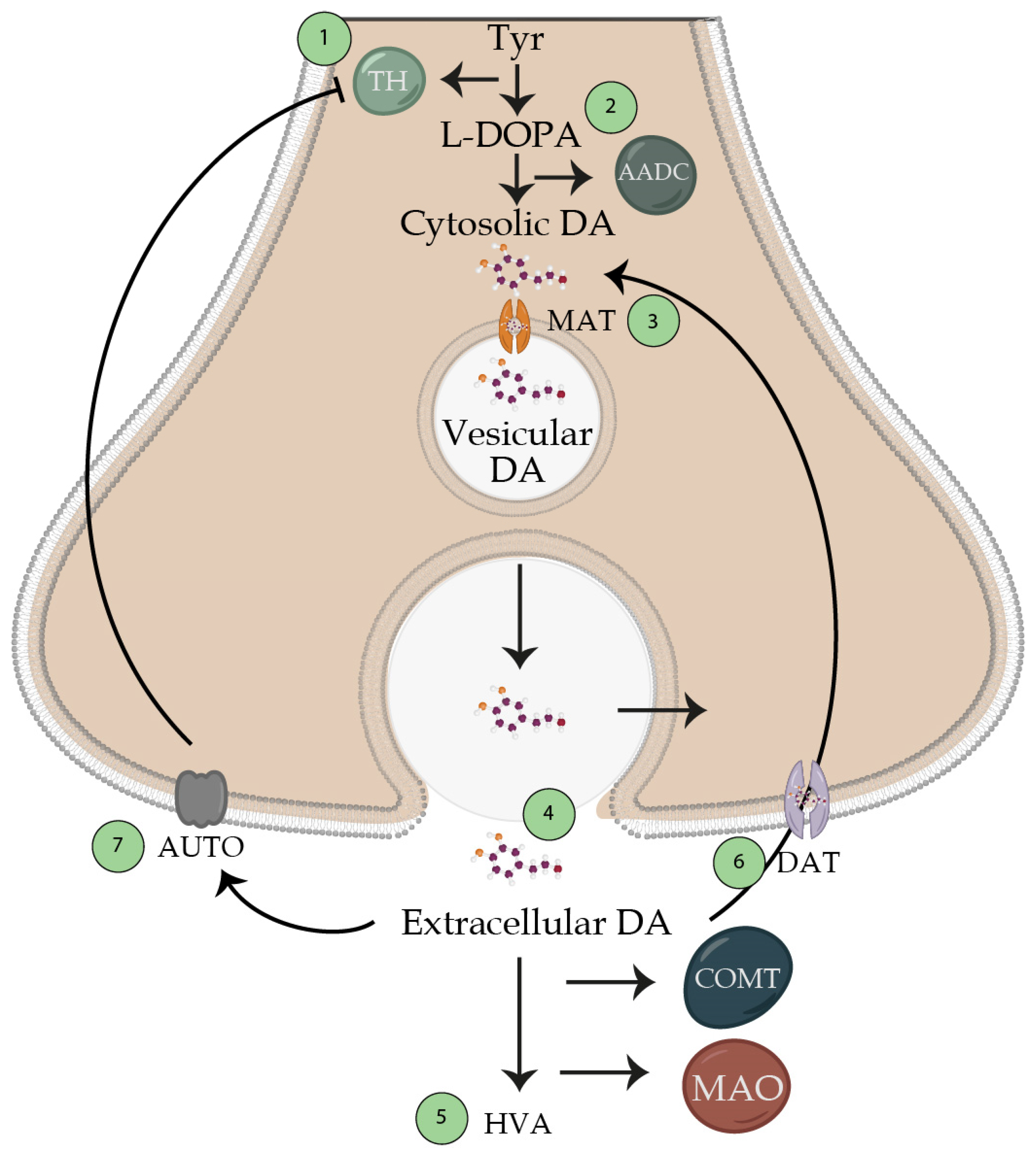

- (a)

- synthesis of dopamine from tyrosine;

- (b)

- accumulation of dopamine by the reserve granules;

- (c)

- dopamine release;

- (d)

- interaction with its receptor;

- (e)

- synaptic reactivation (reuptake) for the subsequent metabolization inactivation (Figure 4).

- The nigrostriatal pathway, which originates in the substantia nigra (group of cells A9) and innervates the caudate putamen (striatum).

- The mesolimbic pathway, which originates in the VTA (A10 cell group) and innervates various limbic system structures such as the nucleus accumbens, the hippocampus, the lateral septum, and the amygdala.

- The mesocortical pathway, which originates in the VTA and innervates the cerebral cortex.

- Somatic (paralysis, balance deficit, etc.);

- Cognitive (aphasia, apraxia, amnesia);

- Emotional and behavioral (psychosis, depression).

4. Superior Functions Affected

4.1. Frontal Functions

4.2. Attention

4.3. Executive Functions

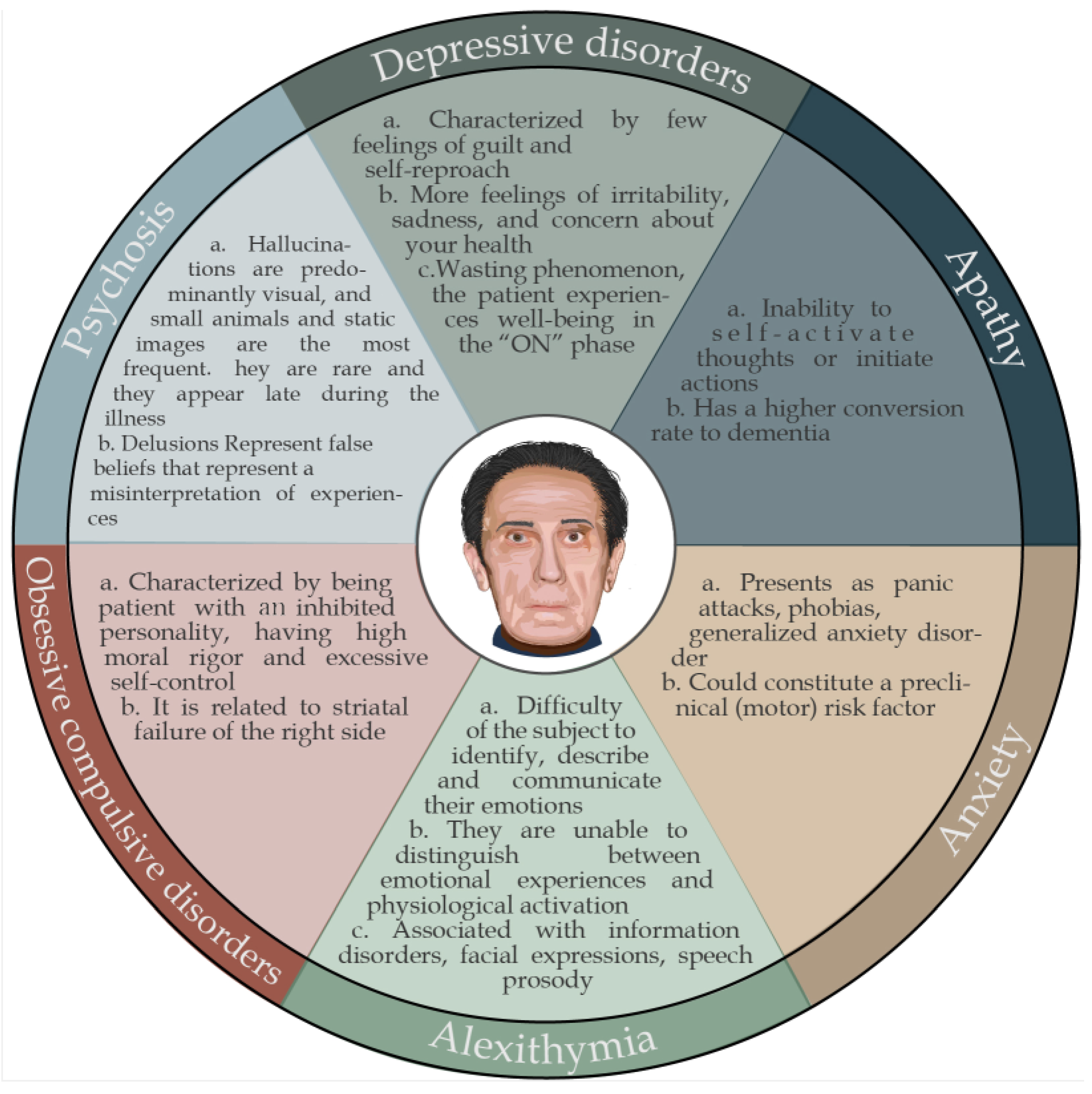

5. Psychiatric Disorders

5.1. Depressive Disorders

5.2. Apathy

5.3. Alexithymia

5.4. Anxiety Disorders

5.5. Obsessive Compulsive Disorders

5.6. Psychosis

5.7. Acute Confusional State

6. Neuropsychological Alterations

6.1. Amnestics and Non-Amnestics

6.2. Memory Disorders

6.3. Working Memory

6.4. Decision-Making Processes

6.5. Language

6.6. Visuospatial Functions

6.7. Praxias

6.8. Calculation

7. Cognitive Disorder–Dementia

8. Neuropsychological–Psychiatric Evaluation

- Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), Wisconsin Card Classification Test (WCST), Figure Classification and Recreation Test, Tower of London Test, Dysexecutive Syndrome Behavioral Assessment (BADS).

- For assessing long-term declarative memory for verbal material, the tests consist of remembering and recognizing passages in prose and word lists: Babcock’s Tale, wordlist learning, and Rey’s 15 Word Test.

- Long-term visuospatial memory is assessed using the Corsi Test. The Corsi Test is also used for long-term declarative memory.

- Short-term memory is evaluated through the Digit Span Test.

- We can use the attentional matrices and the Trail Making Test regarding attention.

- Frontal functions are assessed through the Phonemic and Semantic Fluency Tests and the FAB.

9. Treatment

10. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parkinson, J. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy; Whittingham and Rowland Sherwood: London, UK, 1817. [Google Scholar]

- de Lau, L.M.L.; Breteler, M.M.B. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffard, S.; Verny, M.; Bonnet, A.M.; Beinis, J.Y.; Gallinari, C.; Meaume, S.; Piette, F.; Hauw, J.J.; Duyckaerts, C. Motor score of the unified Parkinson disease rating scale as a good predictor of lewy body-associated neuronal loss in the substantia nigra. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Obeso, J.A.; Stamelou, M.; Goetz, C.G.; Poewe, W.; Lang, A.E.; Weintraub, D.; Burn, D.; Halliday, G.M.; Bezard, E.; Przedborski, S.; et al. Past, present, and future of Parkinson’s disease: A special essay on the 200th Anniversary of the Shaking Palsy. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1264–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, R.F. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016, 22, S119–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, L. Depression and Parkinson’s disease: Current knowledge. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2013, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weintraub, D. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: What geriatric psychiatry can learn. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaudhuri, K.R.; Healy, D.G.; Schapira, A.H.; National Institute for Clinical, E. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapira, A.H.V.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Jenner, P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrag, A.; Taddei, R.N. Depression and Anxiety in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2017, 133, 623–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, L.; McDonald, W.M.; Cummings, J.; Ravina, B.; NINDS/NIMH Work Group on Depression and Parkinson’s Disease. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression in Parkinson’s disease: Report of an NINDS/NIMH Work Group. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, M.H.M.; van Beek, M.; Bloem, B.R.; Esselink, R.A.J. What a neurologist should know about depression in Parkinson’s disease. Pract. Neurol. 2017, 17, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleeng, B.; Dietrichs, E. Unmasking psychiatric symptoms after STN deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 2008, 188, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, V.; Saint-Cyr, J.; Lozano, A.M.; Moro, E.; Poon, Y.Y.; Lang, A.E. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson disease presenting for deep brain stimulation surgery. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 103, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissanayaka, N.N.W.; White, E.; O’Sullivan, J.D.; Marsh, R.; Silburn, P.A.; Copland, D.A.; Mellick, G.D.; Byrne, G.J. Characteristics and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2015, 2, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samudra, N.; Patel, N.; Womack, K.B.; Khemani, P.; Chitnis, S. Psychosis in Parkinson Disease: A Review of Etiology, Phenomenology, and Management. Drugs Aging 2016, 33, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, R.B.; Iourinets, J.; Richard, I.H. Parkinson’s disease psychosis: Presentation, diagnosis and management. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2017, 7, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, G.G.; Pacheco Moisés, F.P.; Mireles-Ramírez, M.; Flores-Alvarado, L.J.; González-Usigli, H.; Sánchez-González, V.J.; Sánchez-López, A.L.; Sánchez-Romero, L.; Díaz-Barba, E.I.; Santoscoy-Gutiérrez, J.F.; et al. Oxidative Stress: Love and Hate History in Central Nervous System. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2017, 108, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspita, L.; Chung, S.Y.; Shim, J.W. Oxidative stress and cellular pathologies in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Brain 2017, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortiz, G.G.; Pacheco-Moisés, F.P.; Mireles-Ramírez, M.A.; Flores-Alvarado, L.J.; González-Usigli, H.; Sánchez-López, A.L.; Sánchez-Romero, L.; Velázquez-Brizuela, I.E.; González-Renovato, E.D.; Torres-Sánchez, E.D. Oxidative Stress and Parkinson’s Disease: Effects on Environmental Toxicology. In Free Radicals and Diseases; InTech: Istambul, Turkey, 2016; pp. 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blauwendraat, C.; Nalls, M.A.; Singleton, A.B. The genetic architecture of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, G.G.; Bitzer-Quintero, O.K.; Charles-Niño, C.L.; Ramírez-Jirano, L.J.; González-Usigli, H.; Pacheco-Moisés, F.P.; Torres-Mendoza, B.M.; Mireles-Ramírez, M.A.; Hernández-Cruz, J.J.; Delgado-Lara, D.L. Microbiome Management of Neurological Disorders. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, R.P.; Chapman, M.R. The role of microbial amyloid in neurodegeneration. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, G.G.; de, L.H.; Cruz-Serrano, J.A.; Torres-Sánchez, E.D.; Mora-Navarro, M.A.; Delgado-Lara, D.L.C.; Gabriela Ortiz-Velázquez, I.; González-Usigli, H.; Bitzer-Quintero, O.K.; Mireles Ramírez, M. Gut-Brain Axis: Role of Microbiota in Parkinson’s Disease and Multiple Sclerosis. In Eat, Learn, Remember; Artis, A.S., Ed.; InTech: Istambul, Turkey, 2019; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McNamara, P.; Durso, R. Neuropharmacological treatment of mental dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Neurol. 2006, 17, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernheimer, H.; Birkmayer, W.; Hornykiewicz, O.; Jellinger, K.; Seitelberger, F. Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington Clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J. Neurol. Sci. 1973, 20, 415–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.J.; Claus, E.D. Anatomy of a decision: Striato-orbitofrontal interactions in reinforcement learning, decision making, and reversal. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 113, 300–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Owen, A.M. Cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: The role of frontostriatal circuitry. Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeterian, E.H.; Pandya, D.N. Prefrontostriatal connections in relation to cortical architectonic organization in rhesus monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991, 312, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, P.D. The Triune Brain in Evolution: Role in Paleocerebral Functions; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, N.; Adolphs, R. Emotion and consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, T.M.; Scarnati, E.; Rosa, I.; Di Censo, D.; Ranieri, B.; Cimini, A.; Galante, A.; Alecci, M. The Basal Ganglia: More than just a switching device. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2018, 24, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Gainetdinov, R.R. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 182–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Best, J.A.; Nijhout, H.F.; Reed, M.C. Homeostatic mechanisms in dopamine synthesis and release: A mathematical model. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2009, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuxe, K. Evidence for the existence of monoamine neurons in the central nervous system—III. The monoamine nerve terminal. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 1965, 65, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednark, J.G.; Campbell, M.E.J.; Cunnington, R. Basal ganglia and cortical networks for sequential ordering and rhythm of complex movements. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aarsland, D.; Brønnick, K.; Larsen, J.P.; Tysnes, O.B.; Alves, G. Cognitive impairment in incident, untreated parkinson disease: The norwegian parkwest study. Neurology 2009, 72, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimović, D.; Post, B.; Speelman, J.D.; Schmand, B. Cognitive profile of patients with newly diagnosed Parkinson disease. Neurology 2005, 65, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Frias, C.M.; Dixon, R.A.; Fisher, N.; Camicioli, R. Intraindividual variability in neurocognitive speed: A comparison of Parkinson’s disease and normal older adults. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 2499–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauntlett-Gilbert, J.; Brown, V.J. Reaction time deficits and Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1998, 22, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarsland, D.; Ballard, C.G.; Halliday, G. Are Parkinson’s disease with dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies the same entity? J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2004, 17, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeith, I.G. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): Report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2006, 47, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, H. The Croonian lectures. Br. Med. J. 1884, 1, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, N.; Brown, P. New insights into the relationship between dopamine, beta oscillations and motor function. Trends Neurosci. 2011, 34, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zald, D.H.; Andreotti, C. Neuropsychological assessment of the orbital and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychologia 2010, 48, 3377–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.L.; Col, N.L.; Doolittle, V.; Martinez, R.R.; Uraga, J.; Whitney, O. Context-dependent activation of a social behavior brain network associates with learned vocal production. Res. Sq. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molas, S.; Zhao-Shea, R.; Freels, T.G.; Tapper, A.R. Viral Tracing Confirms Paranigral Ventral Tegmental Area Dopaminergic Inputs to the Interpeduncular Nucleus Where Dopamine Release Encodes Motivated Exploration. eNeuro 2023, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polito, C.; Berti, V.; Ramat, S.; Vanzi, E.; De Cristofaro, M.T.; Pellicanò, G.; Mungai, F.; Marini, P.; Formiconi, A.R.; Sorbi, S.; et al. Interaction of caudate dopamine depletion and brain metabolic changes with cognitive dysfunction in early Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 206.e29-39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zgaljardic, D.J.; Borod, J.C.; Foldi, N.S.; Mattis, P. A Review of the Cognitive and Behavioral Sequelae of Parkinson’s Disease: Relationship to Frontostriatal Circuitry. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2003, 16, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J.R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 1935, 18, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an Indicator of Organic Brain Damage. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, D.; Moberg, P.J.; Culbertson, W.C.; Duda, J.E.; Katz, I.R.; Stern, M.B. Dimensions of executive function in Parkinson’s disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2005, 20, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuss, D.T.; Levine, B. Adult clinical neuropsychology: Lessons from studies of the frontal lobes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Emory, E. Executive function and the frontal lobes: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2006, 16, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romine, C.B.; Reynolds, C.R. A model of the development of frontal lobe functioning: Findings from a meta-analysis. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2005, 12, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.A.; Berg, E. A behavioral analysis of degree of reinforcement and ease of shifting to new responses in a Weigl-type card-sorting problem. J. Exp. Psychol. 1948, 38, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, S.P.; Tröster, A.I. Prodromal frontal/executive dysfunction predicts incident dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2003, 9, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, B.; Pillon, B. Cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 1996, 244, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. Verbal fluency deficits in Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004, 10, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levy, G.; Jacobs, D.M.; Tang, M.X.; Côté, L.J.; Louis, E.D.; Alfaro, B.; Mejia, H.; Stern, Y.; Marder, K. Memory and executive function impairment predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2002, 17, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, R.; Martinez-Martin, P. Neuropsychiatric symptoms, behavioural disorders, and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 373, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menza, M.A.; Sage, J.; Marshall, E.; Cody, R.; Duvoisin, R. Mood changes and “on-off” phenomena in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 1990, 5, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerts, J.; Leenders, K.L.; Koning, M.; Portman, A.T.; Van Beilen, M. Striatal dopaminergic activity (FDOPA-PET) associated with cognitive items of a depression scale (MADRS) in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 3132–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.J.; Hershey, T.; Hartlein, J.M.; Carl, J.L.; Perlmutter, J.S. Levodopa challenge neuroimaging of levodopa-related mood fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le Heron, C.; Apps, M.A.J.; Husain, M. The anatomy of apathy: A neurocognitive framework for amotivated behaviour. Neuropsychologia 2018, 118, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, R.; Růžička, F.; Bezdicek, O.; Roth, J.; Růžička, E.; Vymazal, J.; Goelman, G.; Jech, R. Impact of dopamine and cognitive impairment on neural reactivity to facial emotion in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 1258–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontone, G.M.; Williams, J.R.; Anderson, K.E.; Chase, G.; Goldstein, S.A.; Grill, S.; Hirsch, E.S.; Lehmann, S.; Little, J.T.; Margolis, R.L.; et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders and anxiety subtypes in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2009, 24, 1333–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicoletti, A.; Luca, A.; Raciti, L.; Contrafatto, D.; Bruno, E.; Dibilio, V.; Sciacca, G.; Mostile, G.; Petralia, A.; Zappia, M. Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder and Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlskog, J.E. Pathological behaviors provoked by dopamine agonist therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 104, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeon, A.; Josephs, K.A.; Klos, K.J.; Hecksel, K.; Bower, J.H.; Michael Bostwick, J.; Eric Ahlskog, J. Unusual compulsive behaviors primarily related to dopamine agonist therapy in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Park. Relat. Disord. 2007, 13, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osa, A.A.; Bowen, T.J.; Whitson, J.T. Charles bonnet syndrome in a patient with Parkinson’s disease and bilateral posterior capsule opacification. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2020, 13, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lizarraga, K.J.; Fox, S.H.; Strafella, A.P.; Lang, A.E. Hallucinations, Delusions and Impulse Control Disorders in Parkinson Disease. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 36, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehagia, A.A.; Barker, R.A.; Robbins, T.W. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: The dual syndrome hypothesis. Neurodegener. Dis. 2012, 11, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnish, M.S.; Horton, S.M.C.; Butterfint, Z.R.; Clark, A.B.; Atkinson, R.A.; Deane, K.H.O. Speech and communication in Parkinson’s disease: A cross-sectional exploratory study in the UK. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bosboom, J.L.W.; Stoffers, D.; Wolters, E.C. Cognitive dysfunction and dementia in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2004, 111, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizak, V.S.; Filoteo, J.V.; Possin, K.L.; Lucas, J.A.; Rilling, L.M.; Davis, J.D.; Peavy, G.; Wong, A.; Salmon, D.P. The ubiquity of memory retrieval deficits in patients with frontal-striatal dysfunction. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2005, 18, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittington, C.; Podd, J.; Stewart-Williams, S. Memory deficits in Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2006, 28, 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, R.; Nyberg, L.; Tulving, E. Hemispheric asymmetries of memory: The HERA model revisited. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittington, C.J.; Podd, J.; Kan, M.M. Recognition memory impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Power and meta-analyses. Neuropsychology 2000, 14, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, A.M.; Brown, R.G.; Marsden, C.D. Levodopa Treatment May Benefit or Impair “Frontal” Function in Parkinson’S Disease. Lancet 1986, 328, 970–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, A.M.; Brown, R.G.; Marsden, C.D. ‘Frontal’ Cognitive Function in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease ‘On’ and ‘Off’ Levodopa. Brain 1988, 111, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzen, H.L.; Levin, B.E.; Weiner, W. Side and type of motor symptom influence cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomer, R.; Aharon-Peretz, J.; Tsitrinbaum, Z. Dopamine asymmetry interacts with medication to affect cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.; Brusa, L.; Oliveri, M.; Stanzione, P.; Caltagirone, C. Memory for time intervals is impaired in left hemi-Parkinson patients. Neuropsychologia 2005, 43, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurvich, C.; Georgiou-Karistianis, N.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Millist, L.; White, O.B. Inhibitory control and spatial working memory in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2007, 22, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, V.A.; Welch, J.L.; Dick, D.J. Visuospatial working memory in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1989, 52, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allamanno, N.; Della Sala, S.; Laiacona, M.; Pasetti, C.; Spinnler, H. Problem solving ability in aging and dementia: Normative data on a non-verbal test. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1987, 8, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechara, A.; Damasio, A.R.; Damasio, H.; Anderson, S.W. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition 1994, 50, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emre, M. What causes mental dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease? Mov. Disord. 2003, 18 (Suppl. S6), S63–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janvin, C.C.; Aarsland, D.; Larsen, J.P. Cognitive predictors of dementia in Parkinson’s disease: A community-based, 4-year longitudinal study. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2005, 18, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monetta, L.; Pell, M.D. Effects of verbal working memory deficits on metaphor comprehension in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Lang. 2007, 101, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.; Durso, R. Pragmatic communication skills in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Lang. 2003, 84, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uc, E.Y.; Rizzo, M.; Anderson, S.W.; Qian, S.; Rodnitzky, R.L.; Dawson, J.D. Visual dysfunction in Parkinson disease without dementia. Neurology 2005, 65, 1907–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosimann, U.P.; Mather, G.; Wesnes, K.A.; O’Brien, J.T.; Burn, D.J.; McKeith, I.G. Visual perception in Parkinson disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2004, 63, 2091–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parnetti, L.; Calabresi, P. Spatial cognition in Parkinson’s disease and neurodegenerative dementias. Cogn. Process. 2006, 7, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, D.; Trojano, L.; Pellecchia, M.T.; Amboni, M.; Fragassi, N.A.; Barone, P. Frontal dysfunction contributes to the genesis of hallucination in non-demented Parkinsonian patients. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiguarda, R.C.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Merello, M.; Starkstein, S.; Lees, A.J.; Marsden, C.D. Apraxia in Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy and neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism. Brain 1997, 120, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahn, S.; Elton, R.L.; UPDRS Development Committee. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Recent Dev. Park. Dis. 2001, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Zadikoff, C.; Lang, A.E. Apraxia in movement disorders. Brain 2005, 128, 1480–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Quencer, K.; Okun, M.S.; Crucian, G.; Fernandez, H.H.; Skidmore, F.; Heilman, K.M. Limb-kinetic apraxia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2007, 68, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, I.; Kikuchi, S.; Otsuki, M.; Kitagawa, M.; Tashiro, K. Deficits of working memory during mental calculation in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2003, 209, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hely, M.A.; Reid, W.G.J.; Adena, M.A.; Halliday, G.M.; Morris, J.G.L. The Sydney Multicenter Study of Parkinson’s disease: The inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Zaccai, J.; Brayne, C. A systematic review of prevalence studies of dementia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2005, 20, 1255–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janvin, C.C.; Larsen, J.P.; Aarsland, D.; Hugdahl, K. Subtypes of mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Progression to dementia. Mov. Disord. 2006, 21, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jin, M.; Wang, L.; Qin, B.; Wang, K. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease in China. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R. Early Diagnosis of Alzheimers Disease: Is MCI Too Late? Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2009, 6, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quelhas, R.; Costa, M. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 21, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaagd, G.; Philip, A. Parkinson’s disease and its management: Part 3: Nondopaminergic and nonpharmacological treatment options. P T 2015, 40, 668–679. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, S.S.; Evans, A.H.; Lees, A.J. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: An overview of its epidemiology, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs 2009, 23, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, N.; O’Gorman, C.; Lehn, A.; Siskind, D. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of published cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Belvisi, D.; Pasquini, M.; Fabbrini, A.; Petrini, F.; Fabbrini, G. Treatment of psychiatric disturbances in hypokinetic movement disorders. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 965–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardelli, I.; Pasquini, M.; Roselli, V.; Biondi, M.; Berardelli, A.; Fabbrini, G. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Movement Disorders: A Review. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2015, 2, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirsch-Darrow, L.; Zahodne, L.B.; Marsiske, M.; Okun, M.S.; Foote, K.D.; Bowers, D. The trajectory of apathy after deep brain stimulation: From pre-surgery to 6 months post-surgery in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2011, 17, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shulman, L.M.; Taback, R.L.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Weiner, W.J. Non-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2002, 8, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weintraub, D.; Moberg, P.J.; Duda, J.E.; Katz, I.R.; Stern, M.B. Effect of psychiatric and other nonmotor symptoms on disability in Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvin, J.E. Cognitive change in Parkinson disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Usigli, H.A.; Ortiz, G.G.; Charles-Niño, C.; Mireles-Ramírez, M.A.; Pacheco-Moisés, F.P.; Torres-Mendoza, B.M.d.G.; Hernández-Cruz, J.d.J.; Delgado-Lara, D.L.d.C.; Ramírez-Jirano, L.J. Neurocognitive Psychiatric and Neuropsychological Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic and Clinical Approach. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030508

González-Usigli HA, Ortiz GG, Charles-Niño C, Mireles-Ramírez MA, Pacheco-Moisés FP, Torres-Mendoza BMdG, Hernández-Cruz JdJ, Delgado-Lara DLdC, Ramírez-Jirano LJ. Neurocognitive Psychiatric and Neuropsychological Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic and Clinical Approach. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(3):508. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030508

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Usigli, Héctor Alberto, Genaro Gabriel Ortiz, Claudia Charles-Niño, Mario Alberto Mireles-Ramírez, Fermín Paul Pacheco-Moisés, Blanca Miriam de Guadalupe Torres-Mendoza, José de Jesús Hernández-Cruz, Daniela Lucero del Carmen Delgado-Lara, and Luis Javier Ramírez-Jirano. 2023. "Neurocognitive Psychiatric and Neuropsychological Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic and Clinical Approach" Brain Sciences 13, no. 3: 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030508

APA StyleGonzález-Usigli, H. A., Ortiz, G. G., Charles-Niño, C., Mireles-Ramírez, M. A., Pacheco-Moisés, F. P., Torres-Mendoza, B. M. d. G., Hernández-Cruz, J. d. J., Delgado-Lara, D. L. d. C., & Ramírez-Jirano, L. J. (2023). Neurocognitive Psychiatric and Neuropsychological Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease: A Basic and Clinical Approach. Brain Sciences, 13(3), 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13030508