The Expression of Affective Temperaments in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Psychopathological Associations and Possible Neurobiological Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessment Scales

- The Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego Autoquestionnaire (TEMPS-A), Italian-validated version [31], including 110 items, to assess temperament characteristics (dysthymic, cyclothymic, hyperthymic, irritable and anxious). The chosen scoring system consisted of assigning 1 point for each positive answer and 0 points for negative answers within the sub-scales (dysthymic items 1–22, cyclothymic items 23–42, hyperthymic items 43–63, irritable items 64–84 and anxious items 85–110) and then calculating the dimensional sums. Item 84 asks specifically about temperament before menstrual cycles and was designated for women only. The Italian version of the TEMPS-A was validated based on a sample of 948 nonclinical subjects (27.39 years ± 8.22 S.D.), including 476 men (50.2%: 28.56 years ± 8.63 S.D.) and 472 women (49.8%: 26.21 years ± 7.61 S.D.). The findings were consistent with those of TEMPS-A studies from different countries. The reliability of the TEMPS-A was assessed using the Cronbach alpha coefficients for the components, and they were quite high; the alpha computed for the first subscale, with the largest number of items, was 0.89, while that for the irritable subscale was 0.77 and that for the hyperthymic subscale was 0.74.

- The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-II Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF), Italian-validated version [32], to evaluate personality characteristics. The MMPI-2-RF is a 338-item (true/false), multiscale, self-report inventory that measures a wide range of psychopathology symptoms and maladaptive personality traits. The 338 MMPI-2-RF items are aggregated onto fifty-one individual scales. Nine of these, the Validity Scales, measure various forms of response styles that, when excessive, could invalidate a test protocol. The remaining forty-two scales measure substantive clinical contents. The three Higher-Order Scales, including Emotional/Internalizing Dysfunction, Thought Dysfunction and Behavioral/Externalizing Dysfunction, index broadband psychopathology constructs of, respectively, internalizing, thought disorder and externalizing. The nine Restructured Clinical Scales reflect transdiagnostic dimensional psychological constructs rather than psychiatric syndromes. The twenty-three Specific Problems Scales, the most narrowband symptom and trait measures in the instrument, are organized into four thematic domains: Somatic/Cognitive, Internalizing, Externalizing and Interpersonal, which also reflect the general interpretive organization of the instrument. The two Interest Scales (Aesthetic–Literary and Mechanical–Physical) primarily measure personality and attitudinal constructs rather than clinical symptoms or traits. Finally, the five Personality Psychopathology Scales are revised versions of their MMPI-2 counterparts, representing dimensional personality traits with an abnormal range and presented as a dimensional alternative to the categorical personality disorder framework that dominates the DSM.

- The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Italian-validated version [33], to assess depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure for assessing and screening the severity of depressive symptoms. For each item, patients are asked to assess how much they have been bothered by symptoms over the last 2 weeks. There are 4 answer options: not at all (0), several days (1), more than half of the days (2) and nearly every day (3). The sum score (range 0–27) indicates the degree of depression, with scores of ≥5, ≥10 and ≥15 representing mild, moderate and severe levels of depression.

- The General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire to assess anxiety symptoms [34]. The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report measure for assessing and screening generalized anxiety disorder and its severity during the past 2 weeks. The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘Not at all’) to 3 (‘Nearly every day’), with a total score ranging from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate higher levels of generalized anxiety. Scores ranging from 10 to 14 indicate generalized anxiety of moderate severity, and scores ranging from 15 to 21 indicate severe generalized anxiety. For our study, we used the official Italian version, which is freely downloadable from the PHQ website (http://www.phqscreeners.com, accessed on 4 April 2023).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

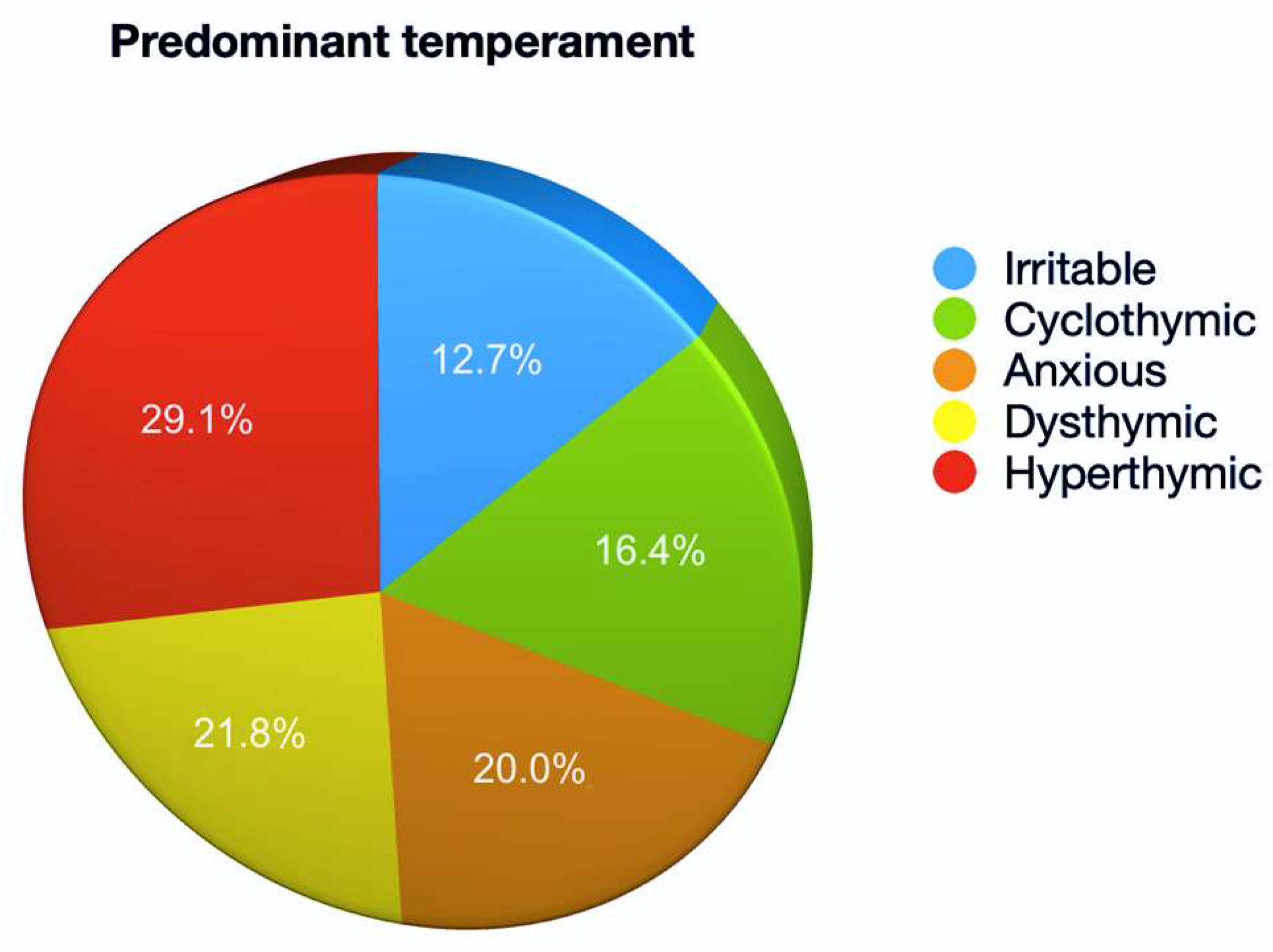

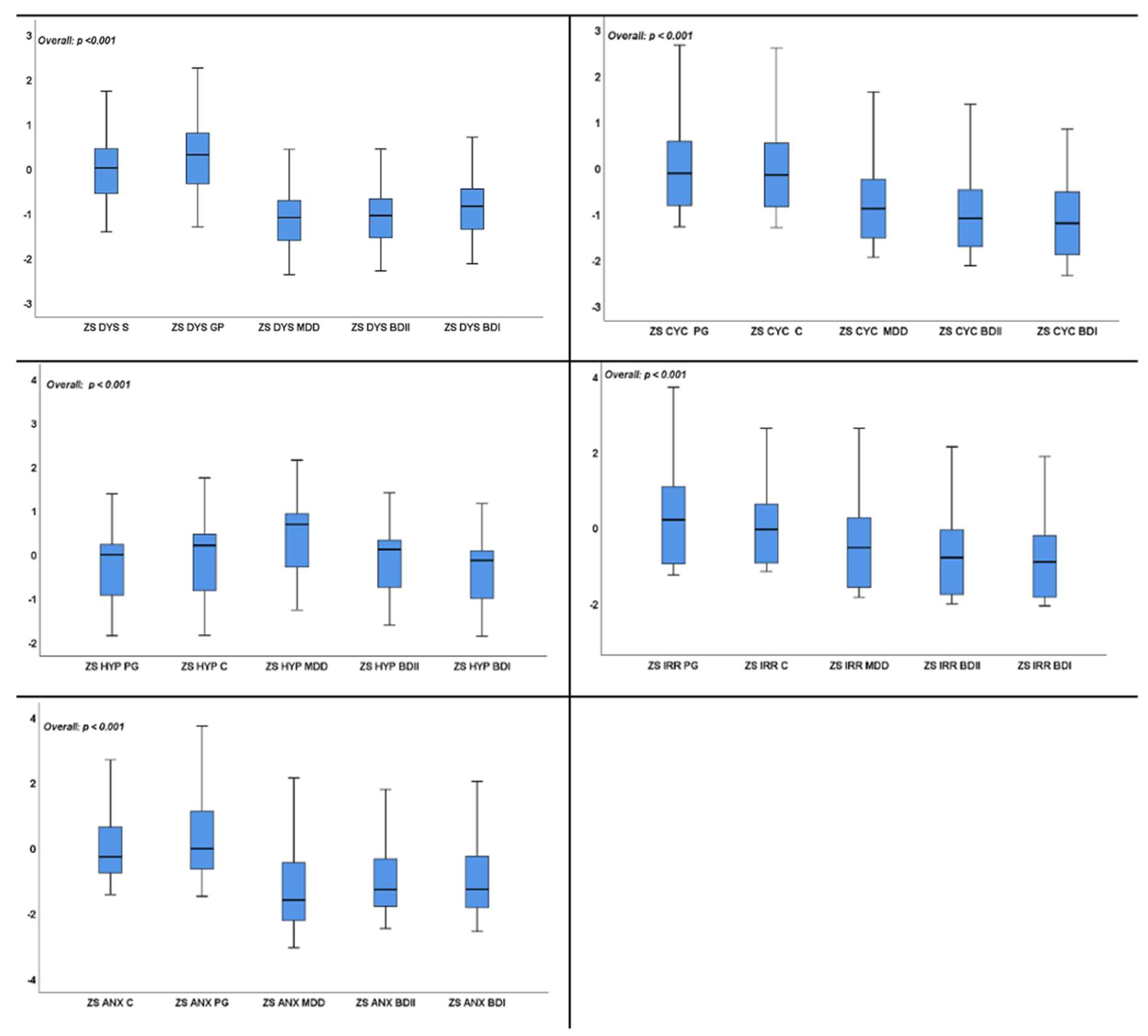

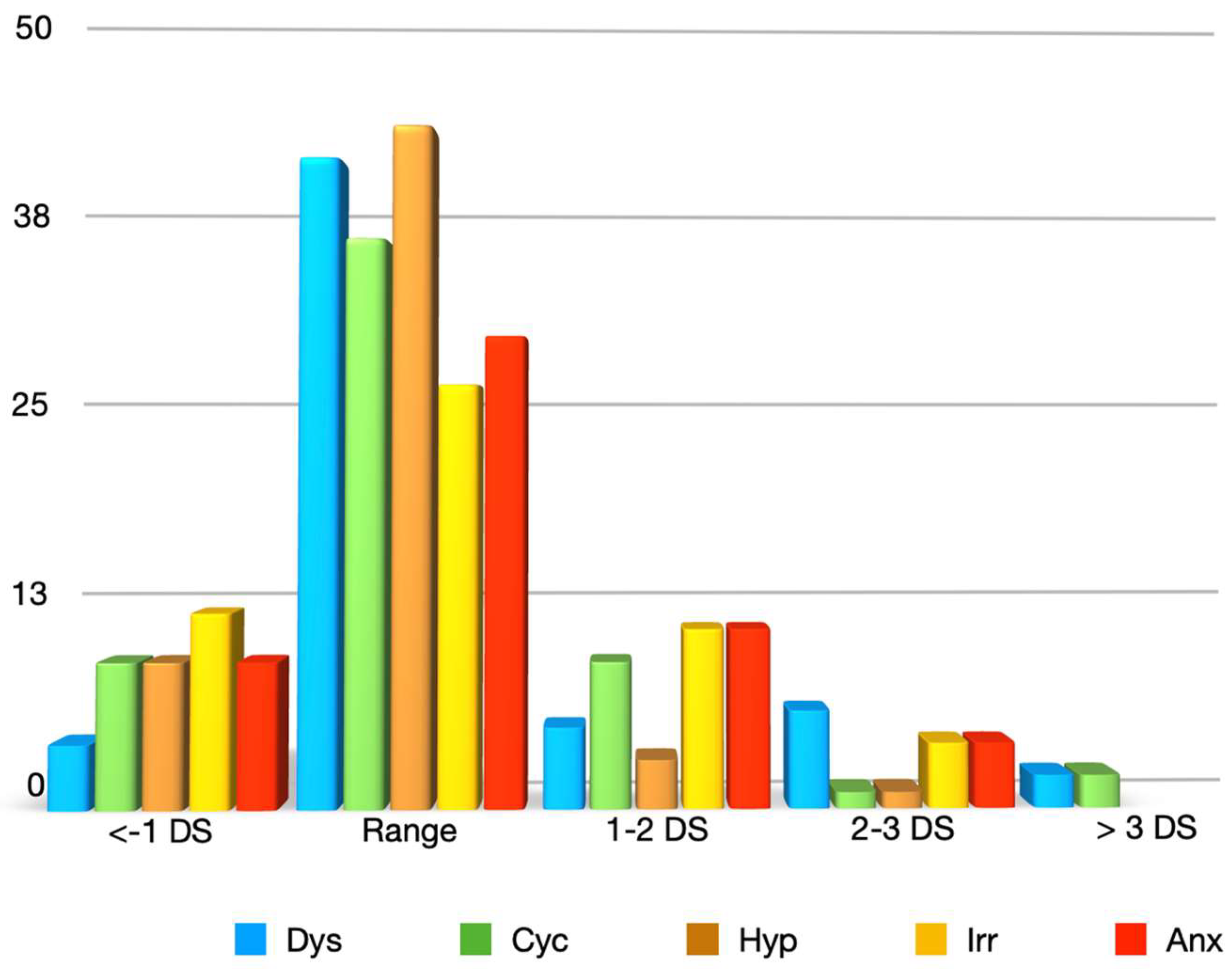

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eliade, M.; Jesi, F. Lo Yoga: Immortalità e Libertà; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhoff, K. Essays in the History of Medicine. In Translated by Various Hands and Edited, with Foreword and Biographical Sketch; Fielding, H., Garrison, M.L., Eds.; Books for Libraries Press: Freeport, NY, USA, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, J. Galen’s Prophecy: Temperament in Human Nature; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Derryberry, D. Development of individual difference in temperament. In Advances in Developmental Psychology; Lamb, M.E., Brown, A.L., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- Joncich, G.; Kessen, W. The Child; Kessen, W., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1966; Volume 6, pp. 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zentner, M.; Bates, J. Child temperament: An integrative review of concepts, research programs, and measures. Eur. J. Dev. Sci. 2008, 2, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K. Le Personalità Psicopatiche; Giovanni Fioriti Editore: Roma, Italy, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin, E. Manic-Depressive Insanity and Paranoia (Classics in Psychiatry); Emil Kraepelin, E., Livingstone, S., Eds.; Ayer Co Pub: Stratford, NH, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.S. The theoretical underpinnings of affective temperaments: Implications for evolutionary foundations of bipolar disorder and human nature. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, L.; Solmi, M.; Toffanin, T.; Veronese, N.; Cloninger, C.R.; Correll, C.U. A meta-analysis of temperament and character dimensions in patients with mood disorders: Comparison to healthy controls and unaffected siblings. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 194, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeorge, D.P.; Walsh, M.A.; Barrantes-Vidal, N.; Kwapil, T.R. A three-year longitudinal study of affective temperaments and risk for psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 164, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Akiskal, K.; Allilaire, J.F.; Azorin, J.M.; Bourgeois, M.L.; Sechter, D.; Fraud, J.P.; Chatenêt-Duchêne, L.; Lancrenon, S.; Perugi, G.; et al. Validating affective temperaments in their subaffective and socially positive attributes: Psychometric, clinical and familial data from a French national study. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihmer, Z.; Akiskal, K.K.; Rihmer, A.; Akiskal, H.S. Current research on affective temperaments. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Rihmer, Z.; Gonda, X.; Serafini, G.; Akiskal, H.; Amore, M.; Niolu, C.; Sher, L.; Tatarelli, R.; et al. Cyclothymic-depressive-anxious temperament pattern is related to suicide risk in 346 patients with major mood disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, G.H.; Gonda, X.; Zaratiegui, R.; Lorenzo, L.S.; Akiskal, K.; Akiskal, H.S. Hyperthymic temperament may protect against suicidal ideation. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 127, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, C.; Croft, J.; Zammit, S. Examining the relationship between early childhood temperament, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 144, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marder, E.; Bucher, D. Central pattern generators and the control of rhythmic movements. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, R986–R996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsop, T.A.; Lang, E.J. Block of Inferior Olive Gap Junctional Coupling Decreases Purkinje Cell Complex Spike Synchrony and Rhythmicity. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, Y.M.; Dragomir, A.; Song, C.; Wu, J.; Akay, M. Hippocampal gamma oscillations in rats. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2009, 28, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunze, H.C.R.; Langosch, J.; Normann, C.; Rujescu, D.; Amann, B.; Waiden, J. Dysregulation of ion fluxes in bipolar affective disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2000, 12, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Khani, M.K.; Scott-Strauss, A. Cyclothymic Temperamental Disorders. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1979, 2, 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybakowski, J.K.; Dembinska, D.; Kliwicki, S.; Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.H. TEMPS-A and long-term lithium response: Positive correlation with hyperthymic temperament. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 145, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Pacheco, M. CFTR Modulators: The Changing Face of Cystic Fibrosis in the Era of Precision Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shteinberg, M.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L. Impact of CFTR modulator use on outcomes in people with severe cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 190112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havermans, T.; Willem, L. Prevention of anxiety and depression in cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2019, 25, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quittner, A.L.; Goldbeck, L.; Abbott, J.; Duff, A.; Lambrecht, P.; Solé, A.; Tibosch, M.M.; Brucefors, A.B.; Yüksel, H.; Catastini, P.; et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: Results of The International Depression Epidemiological Study across nine countries. Thorax 2014, 69, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, M.E.; Eakin, M.N.; Borrelli, B.; Green, A.; Riekert, K.A. Medication beliefs mediate between depressive symptoms and medication adherence in cystic fibrosis. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, M.S.; Ostrenga, J.S.; Fink, A.K.; Barker, D.H.; Sawicki, G.S.; Quittner, A.L. Decreased survival in cystic fibrosis patients with a positive screen for depression. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerio, A.; Sibilla, F.; Pescini, R.; Ciprandi, R.; Casciaro, R.; Grimaldi Filioli, P.; Porcelli, C.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Aguglia, A.; et al. Mental health and cystic fibrosis: Time to move from secondary prevention to predictive medicine. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 2204–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pompili, M.; Girardi, P.; Tatarelli, R.; Iliceto, P.; De Pisa, E.; Tondo, L.; Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.S. TEMPS-A (Rome): Psychometric validation of affective temperaments in clinically well subjects in mid- and south Italy. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 107, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirigatti, S.; Faravelli, C. MMPI-2-RF: Adattamento Italiano. Taratura, Proprietà Psicometriche e Correlati Empirici; Giunti O.S. Organizzazioni Speciali: Florence, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotti, E.; Fassone, G.; Picardi, A.; Sagoni, I.; Ramieri, L.; Lega, D.; Camaioni, D.; Abeni, D.; Pasquini, P. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for the screening of psychiatric disorders: A validation study versus the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I (SCID-I). J. Psychopathol. 2003, 9, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, G.H.; Tondo, L.; Mazzarini, L.; Gonda, X. Affective temperaments in general population: A review and combined analysis from national studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Gonda, X.; Erbuto, D.; Forte, A.; Ricci, F.; Lester, D.; Akiskal, H.S.; Vázquez, G.H.; Rihmer, Z.; et al. Characterization of patients with mood disorders for their prevalent temperament and level of hopelessness. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 166, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.H.; Nasetta, S.; Mercado, B.; Romero, E.; Tifner, S.; Ramón, M.d.L.; Garelli, V.; Bonifacio, A.; Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.S. Validation of the TEMPS-A Buenos Aires: Spanish psychometric validation of affective temperaments in a population study of Argentina. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 100, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Toni, C.; Maremmani, I.; Tusini, G.; Ramacciotti, S.; Madia, A.; Fornaro, M.; Akiskal, H.S. The influence of affective temperaments and psychopathological traits on the definition of bipolar disorder subtypes: A study on bipolar I Italian national sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 136, e41–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, T.A.; Akiskal, H.S.; Akiskal, K.K.; Kelsoe, J.R. Genome-wide Association Study of Temperament in Bipolar Disorder Reveals Significant Associations to Three Novel Loci. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesebir, S.; Vahip, S.; Akdeniz, F.; Yüncü, Z.; Alkan, M.; Akiskal, H. Affective temperaments as measured by TEMPS-A in patients with bipolar I disorder and their first-degree relatives: A controlled study. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R. Mechanisms in manic-depressive disorder: An evolutionary model. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1982, 39, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Mendlowicz, M.V.; Jean-Louis, G.; Rapaport, M.H.; Kelsoe, J.R.; Gillin, J.C.; Smith, T.L. TEMPS-A: Validation of a short version of a self-rated instrument designed to measure variations in temperament. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 85, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karam, E.G.; Salamoun, M.M.; Yeretzian, J.S.; Mneimneh, Z.N.; Karam, A.N.; Fayyad, J.; Hantouche, E.; Akiskal, K.; Akiskal, H.S. The role of anxious and hyperthymic temperaments in mental disorders: A national epidemiologic study. World Psychiatry 2010, 9, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, P.; Hranov, L.G. EPA-0478—Hyperthymic temperament as a protective factor against suicidal risk. Eur. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, G.H.; Gonda, X.M.A.; Lolich, M.; Tondo, L.; Baldessarini, R.J. Suicidal Risk and Affective Temperaments, Evaluated with the TEMPS-A Scale: A Systematic Review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 26, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugi, G.; Cesari, D.; Vannucchi, G.; Maccariello, G.; Barbuti, M.; De Bartolomeis, A.; Fagiolini, A.; Maina, G. The impact of affective temperaments on clinical and functional outcome of Bipolar I patients that initiated or changed pharmacological treatment for mania. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, M.; Steardo, L.; Sampogna, G.; Caivano, V.; Ciampi, C.; Del Vecchio, V.; Di Cerbo, A.; Giallonardo, V.; Zinno, F.; De Fazio, P.; et al. Affective Temperaments and Illness Severity in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Medicina 2021, 57, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Innamorati, M.; Gonda, X.; Serafini, G.; Sarno, S.; Erbuto, D.; Palermo, M.; Elena Seretti, M.; Stefani, H.; Lester, D.; et al. Affective temperaments and hopelessness as predictors of health and social functioning in mood disorder patients: A prospective follow-up study. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iasevoli, F.; Valchera, A.; Di Giovambattista, E.; Marconi, M.; Rapagnani, M.P.; De Berardis, D.; Martinotti, G.; Fornaro, M.; Mazza, M.; Tomasetti, C.; et al. Affective temperaments are associated with specific clusters of symptoms and psychopathology: A cross-sectional study on bipolar disorder inpatients in acute manic, mixed, or depressive relapse. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiskal, H.S.; Pinto, O. The evolving bipolar spectrum. Prototypes I, II, III, and IV. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 122, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baertschi, M.; Costanza, A.; Canuto, A.; Weber, K. The Function of Personality in Suicidal Ideation from the Perspective of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murlanova, K.; Michaelevski, I.; Kreinin, A.; Terrillion, C.; Pletnikov, M.; Pinhasov, A. Link between temperament traits, brain neurochemistry and response to SSRI: Insights from animal model of social behavior. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoaki, N.; Terao, T.; Wang, Y.; Goto, S.; Tsuchiyama, K.; Iwata, N. Biological aspect of hyperthymic temperament: Light, sleep, and serotonin. Psychopharmacology 2011, 213, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faedda, G.L.; Marangoni, C.; Reginaldi, D. Depressive mixed states: A reappraisal of Koukopoulos’ criteria. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 176, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Angst, J.; Azorin, J.M.; Bowden, C.L.; Mosolov, S.; Reis, J.; Vieta, E.; Young, A.H. Mixed features in patients with a major depressive episode: The BRIDGE-II-MIX study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, e351–e358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, J.; Benazzi, F.; Rihmer, Z.; Rihmer, A.; Akiskal, K.K.; Akiskal, H.S. The close link between suicide attempts and mixed (bipolar) depression: Implications for suicide prevention. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 91, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, G.B.; Akiskal, H.S.; Musetti, L.; Pentgi, G.; Soriani, A.; Mignani, V. Psychopathology, temperament, and past course in primary major depressions. 2. Toward a redefinition of bipolarity with a new semistructured interview for depression. Psychopathology 1989, 22, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, L.L.; Schettler, P.J.; Akiskal, H.; Coryell, W.; Fawcett, J.; Fiedorowicz, J.G.; Solomon, D.A.; Keller, M.B. Prevalence and clinical significance of subsyndromal manic symptoms, including irritability and psychomotor agitation, during bipolar major depressive episodes. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, M.; Pirozzi, R.; Magliano, L.; Fiorillo, A.; Bartoli, L. Agitated “unipolar” major depression: Prevalence, phenomenology, and outcome. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006, 67, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, G.; Tondo, L.; Koukopoulos, A.; Reginaldi, D.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Koukopoulos, A.E.; Manfredi, G.; Mazzarini, L.; Pacchiarotti, I.; Simonetti, A.; et al. Suicide in a large population of former psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, H.M.; Suominen, K.; Haukka, J.; Mantere, O.; Leppämäki, S.; Arvilommi, P.; Isometsä, E.T. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts during phases of bipolar I and II disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008, 10, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinzie, C.J.; Goralski, J.L.; Noah, T.L.; Retsch-Bogart, G.Z.; Prieur, M.B. Worsening anxiety and depression after initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination therapy in adolescent females with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwalkar, J.S.; Koff, J.L.; Lee, H.B.; Britto, C.J.; Mulenos, A.M.; Georgiopoulos, A.M. Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator Modulators: Implications for the Management of Depression and Anxiety in Cystic Fibrosis. Psychosomatics 2017, 58, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Female | Male | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.3 ± 10.94 (19.0−60.0) | 34.9 ± 12.07 (19.0−60.0) | 32.9 ± 7.65 (22.0−48.0) | |

| Gender | Female | 39 (70.9%) | 39 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Male | 16 (29.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (100.0%) | |

| CFTR modulation therapy | 40 (72.7%) | 31 (79.5%) | 9 (56.3%) | |

| Prior psychopathologic episodes | 30 (54.5%) | 26 (66.7%) | 4 (25.0%) | |

| Number of prior psychopathologic episodes | 2.2 ± 0.92 (0.0−4.0) | 2.2 ± 0.98 (0.0−4.0) | 2.3 ± 0.50 (2.0−3.0) | |

| Presence of at least one psychiatric diagnosis | 34 (61.8%) | 27 (69.2%) | 7 (43.8%) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 27 (49.1%) | 21 (53.8%) | 6 (37.5%) | |

| Depressive disorder | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (5.1%) | 1 (6.3%) | |

| Cyclothymic mood disorder | 6 (10.9%) | 6 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Dissociative disorder | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Dysthymic disorder | 9 (16.4%) | 5 (12.8%) | 4 (25.0%) | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 1 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Eating disorder | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amerio, A.; Magnani, L.; Castellani, C.; Schiavetti, I.; Sapia, G.; Sibilla, F.; Pescini, R.; Casciaro, R.; Cresta, F.; Escelsior, A.; et al. The Expression of Affective Temperaments in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Psychopathological Associations and Possible Neurobiological Mechanisms. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040619

Amerio A, Magnani L, Castellani C, Schiavetti I, Sapia G, Sibilla F, Pescini R, Casciaro R, Cresta F, Escelsior A, et al. The Expression of Affective Temperaments in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Psychopathological Associations and Possible Neurobiological Mechanisms. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(4):619. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040619

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmerio, Andrea, Luca Magnani, Carlo Castellani, Irene Schiavetti, Gabriele Sapia, Francesca Sibilla, Rita Pescini, Rosaria Casciaro, Federico Cresta, Andrea Escelsior, and et al. 2023. "The Expression of Affective Temperaments in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Psychopathological Associations and Possible Neurobiological Mechanisms" Brain Sciences 13, no. 4: 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040619

APA StyleAmerio, A., Magnani, L., Castellani, C., Schiavetti, I., Sapia, G., Sibilla, F., Pescini, R., Casciaro, R., Cresta, F., Escelsior, A., Costanza, A., Aguglia, A., Serafini, G., Amore, M., & Ciprandi, R. (2023). The Expression of Affective Temperaments in Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Psychopathological Associations and Possible Neurobiological Mechanisms. Brain Sciences, 13(4), 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13040619