Associations Between DCD Traits, Perceived Difficulties Related to ADHD, ASD, and Reading and Writing Support Needs Among Students in Higher Education: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

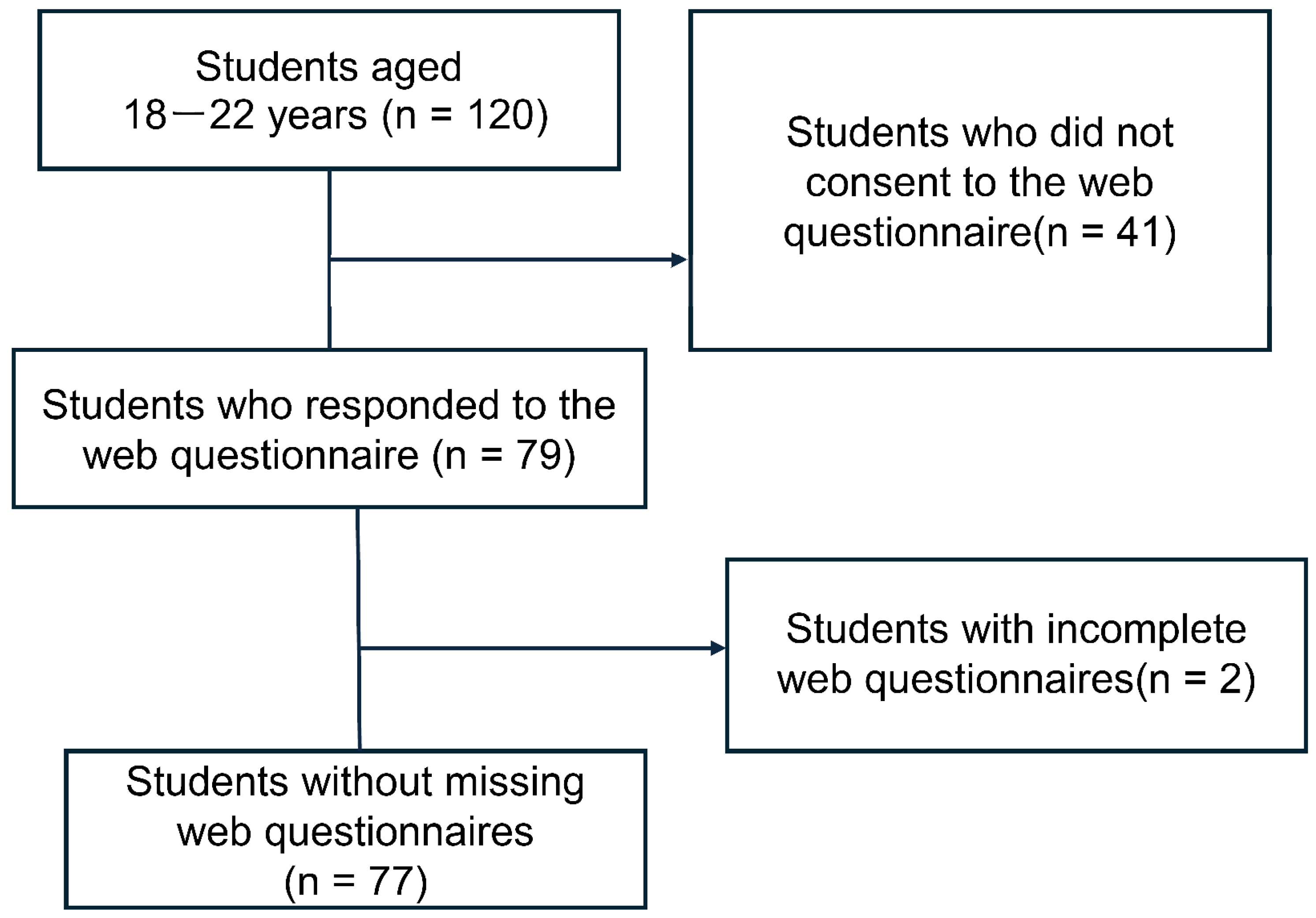

2.1. Participants

2.2. Survey Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. The Adolescents and Adults Coordination Questionnaire

2.3.2. Developmental Disorders Difficulty Scales (Survey on Difficulties in University Life)

ADHD Difficulty Scale

ASD Difficulty Scale

2.3.3. Reading and Writing Support Needs Scale

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Overall Results

3.2. Correlation Among AAC-Q, ADHD Difficulty Scale, ASD Difficulty Scale, LDSP7, and SCLD10

3.3. Correlation Between AAC-Q, ADHD Difficulty Scale, ASD Difficulty Scale, LDSP7, and SCLD10 in Groups with and Without DCD Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of DCD Traits and Difficulties with ADHD, ASD, and SLD in Higher Education Institutions

4.2. Association Between DCD Traits and ADHD, ASD, and SLD Difficulties in 77 Participants

4.3. Association Between AAC-Q and Developmental Disability Difficulty Scales in Groups with and Without DCD Traits

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 2019–2020 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:20). 2022. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_311.10.asp (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Hubble, S.; Bolton, P. Support for Disabled Students in Higher Education in England (Commons Library Briefing: CBP-8716); House of Commons Library: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://parliament.uk/CBP-8716.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Cabinet Office. Act for Eliminating Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities, Act No. 65. 2013. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/shougai/suishin/law_h25-65.html (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Japan Student Services Organization. Report on the Actual Condition of Learning Support for Students with Disabilities in Universities, Junior Colleges, and Technical Colleges for the Fiscal Year. 2023. Available online: https://x.gd/s2h3z (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Takahashi, C.; Sasaki, G.; Nakano, Y. Assessment of University Students with Developmental Disabilities: A Guide to Understanding and Support, 1st ed.; Kaneko: Shobo, Tokyo, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Harada, S. The relationship between difficulties related to neurodevelopmental disorders, motivation decline, and stress responses among university students. High. Educ. Disabil. 2019, 1, 45–51. Available online: https://ahead-japan.org/journal/01-01/vol01-no01-05.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Shinoda, H.; Nakazue, S.; Shinoda, N.; Takahashi, C. Support Needs Related to Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Support for Academic Transition Skills among University Students. Rissho Univ Bull. Inst. Psychol. 2017, 15, 7–17. Available online: https://rissho.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/5642 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Blank, R.; Barnett, A.L.; Cairney, J.; Green, D.; Kirby, A.; Polatajko, H.; Rosenblum, S.; Smits-Engelsman, B.; Sugden, D.; Wilson, P.; et al. International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 242–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linde, B.W.; van Netten, J.J.; Otten, B.; Postema, K.; Geuze, R.H.; Schoemaker, M.M. Activities of Daily Living in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder: Performance, Learning, and Participation. Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingam, R.; Jongmans, M.J.; Ellis, M.; Hunt, L.P.; Golding, J.; Emond, A. Mental Health Difficulties in Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e882–e891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal-Saban, M.; Zarka, S.; Grotto, I.; Ornoy, A.; Parush, S. The functional profile of young adults with suspected developmental coordination disorder (DCD). Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 2193–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal-Saban, M.; Ornoy, A.; Parush, S. Young adults with developmental coordination disorder: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 68, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, M.; Leonard, H.C.; Hill, E.L.; Henry, L.A. Brief report: Response inhibition and processing speed in children with motor difficulties and developmental coordination disorder. Child Neuropsychol. 2016, 22, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, A. Commonly used assessment tools in the field of developmental disorders: Assessment of coordination movement–DCDQR, MABC2. In Guidelines for Support and Assessment of Children and Adults with Developmental Disabilities; Tsujii, M., Akatani, M., Eds.; Kaneko: Shobo, Tokyo, 2014; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, A.; Sugden, D.; Beveridge, S.; Edwards, L. Developmental coordination disorders (DCD) in adolescents and adults in higher education. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2008, 8, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon-Roy, M.; Jasmin, E.; Camden, C. Social participation of teenagers and young adults with developmental co-ordination disorder and strategies that could help them: Results from a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2016, 42, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Iwataki, D.; Tajima, Y. Self-perception of clumsiness in adolescence–its relationship with communi-cation skills and sense of adaptation. Bull. Res. Inst. Life Psychol. Showa Women’s Univ. 2017, 19, 71–82. Available online: https://swu.repo.nii.ac.jp/?action=repository_uri&item_id=6215&file_id=22&file_no=1 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Takahashi, C.; Iwabuchi, M.; Suda, N.; Oda, K.; Yamasaki, I.; Hariba, S.; Morimitsu, A.; Kaneko, M.; Washizuka, S.; Kamimura, E.; et al. Manual for the Implementation of the Developmental Disorder Difficulties Questionnaire, 1st ed.; Sankei-sha: Kyoto, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, C.; Iwabuchi, M.; Suda, N.; Oda, K.; Yamasaki, I.; Hariba, S.; Morimitsu, A.; Kaneko, M.; Washizuka, S.; Kamimura, E.; et al. Manual for the Implementation of the Developmental Disorder Difficulties Questionnaire, 2nd ed.; Sankei-sha: Kyoto, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, C.; Mitani, E. Connecting Support for Reading and Writing Difficulties: Reading and Writing Assessment for University Students–Reading and Writing Tasks (RaWF) and the Reading and Writing Support Needs Scale (RaWSN); Kaneko: Shobo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tal-Saban, M.T.; Ornoy, A.; Grotto, I.; Parush, S. Adolescent and adult coordination questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2012, 66, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biotteau, M.; Danna, J.; Baudou, É.; Puyjarinet, F.; Velay, J.L.; Albaret, J.M.; Chaix, Y. Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: Signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramus, F.; Pidgeon, E.; Frith, U. The relationship between motor control and phonology in dyslexic children. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Student Services Organization. Report on the Actual Condition of Learning Support for Students with Disabilities in Universities, Junior Colleges, and Technical Colleges for the Fiscal Year. 2013. Available online: https://x.gd/7ezap (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Fliers, E.; Rommelse, N.; Vermeulen, S.H.H.M.; Altink, M.; Buschgens, C.J.M.; Faraone, S.V.; Sergeant, J.A.; Franke, B.; Buitelaar, J.K. Motor coordination problems in children and adolescents with ADHD rated by parents and teachers: Effects of age and gender. J. Neural Transm. 2008, 115, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilroy, E.; Ring, P.; Hossain, A.; Nalbach, A.; Butera, C.; Harrison, L.; Jayashankar, A.; Vigen, C.; Aziz-Zadeh, L.; Cermak, S.A. Motor performance, praxis, and social skills in autism spectrum disorder and developmental coordination disorder. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 1649–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Charman, T.; Pickles, A.; Chandler, S.; Loucas, T.; Simonoff, E.; Baird, G. Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingam, R.; Golding, J.; Jongmans, M.J.; Hunt, L.P.; Ellis, M.; Emond, A. The association between developmental coordination disorder and other developmental traits. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e1109–e1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.N.; Neil, K.; Kamps, P.H.; Babcock, S. Awareness and knowledge of developmental coordination disorders among physicians, teachers and parents. Health Dev. 2013, 39, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, E.; Crane, L.; Hill, E.L. Examining academic confidence and study support needs for university students with dyslexia and/or developmental coordination disorder. Dyslexia 2021, 27, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, A.; Tamamura, K. Support for Students with Developmental Disabilities in Higher Education—Focusing on the “Survey on Support for Students with Developmental Disabilities” in Five Prefectures in the Kansai Region. Bull. Nara Univ. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2009, 58, 69–78. Available online: https://nara-edu.repo.nii.ac.jp/records/12493 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Yamamoto, Y.; Tanaka, R. Fukuoka University Research Promotion Division. Fukuoka Univ. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 54, 1–17. Available online: https://fukuoka-u.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/2000085/files/G5401_allpages.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Uchino, T. Research on Support and Reasonable Accommodation for Students with Developmental Disabilities. Comprehensive Health Science. Hiroshima Univ. Health Serv. Cent. Res. Bull. 2017, 33, 39–50. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/222961243.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Forde, J.J.; Smyth, S. Avoidance behavior in adults with developmental coordination disorder is related to quality of life. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 34, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.R.; Shaw, S.C.K.; Anderson, J.L. Dyspraxia in Medical Education: Collaborative Autoethnography. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 4072–4093. Available online: https://ur0.jp/IXnI1 (accessed on 20 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Verlinden, S.; De Wijngaert, P.; Van den Eynde, J. Developmental coordination disorder in adults: A case series of conditions underdiagnosed by an adult psychiatrist. Psychiatry Res. Case Rep. 2023, 2, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, C.; Scott-Roberts, S.; Kirby, A. Implications of the DSM-5 in recognizing adults and developmental coordination disorder (DCD). Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 78, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.; Jijon, A.M.; Leonard, H.C. Research review: Internalizing symptoms in developmental coordination disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairney, J.; Veldhuizen, S.; Szatmari, P. Motor coordination and emotional–behavioral problems in children. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 23, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcome Measure | Group with DCD Traits | Group Without DCD Traits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 10) | (n = 67) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | p-Value | Effect Size | |

| (25th–75th Percentile) | (25th–75th Percentile) | |||||

| Sex | 1 male, 9 females | 14 males, 52 females, 1 other | 0.001 † | 0.14 | ||

| Age | 19.2 (0.79) | 19 (18.75–20) | 19.16 (0.67) | 19 (19–19) | 0.894 ‡ | 0.02 |

| AAC-Q | ||||||

| Total score | 37.1 (7.14) | 35 (31.25–43.25) | 17.75 (4.49) | 18 (14–22) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.93 |

| ADHD | ||||||

| Total score | 15.2 (6.60) | 14.5 (9.50–18.75) | 5.24 (4.74) | 4 (1–8) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.56 |

| Concentration | 2.2 (0.92) | 2 (1.75–3.00) | 0.78 (0.78) | 1 (0–1) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.52 |

| Inattention | 4.0 (1.56) | 4 (2.75–6.00) | 1.12 (1.67) | 0 (0–2) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.51 |

| Impulsivity | 2.1 (1.60) | 1.5 (1.0–3.0) | 0.61 (1.01) | 0 (0–1) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.42 |

| Sleep | 1.4 (1.26) | 1 (0–3.0) | 0.79 (0.93) | 0 (0–1) | 0.070 ‡ | 0.21 |

| Planning | 1.7 (1.42) | 1.5 (0.75–2.50) | 0.60 (0.89) | 0 (0–1) | 0.001 ‡ | 0.36 |

| Clumsiness | 3.8 (1.75) | 4 (2.0–4.25) | 1.34 (1.40) | 0 (0–2) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.5 |

| ASD | ||||||

| Total score | 16.3 (7.33) | 16.5 (10–21.25) | 5.78 (5.29) | 4 (2–8) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.54 |

| Autism | 10.6 (4.17) | 11 (6.0-14.25) | 3.33 (3.19) | 3 (1–5) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.6 |

| Interpersonal | 5.7 (3.47) | 6 (3.25–7.75) | 2.45 (2.76) | 1 (0–4) | 0.001 ‡ | 0.36 |

| SLD | ||||||

| LDSPt7 total score | 12.1 (3.51) | 13 (8.75–14) | 7.96 (1.55) | 7 (7–9) | 0.005 ‡ | 0.6 |

| SCLD10 total score | 15 (2.98) | 15 (11.75–18) | 11.21 (2.54) | 10 (10–11) | 0.000 ‡ | 0.45 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AAC-Q-TS | ― | ||||||||||||

| 2. ADHD-TS | 0.650 ** | ― | |||||||||||

| [0.49,0.77] | |||||||||||||

| 3. ADHD-CO | 0.515 ** | 0.781 ** | ― | ||||||||||

| [0.33,0.67] | [0.67,0.86] | ||||||||||||

| 4. ADHD-INA | 0.588 ** | 0.773 ** | 0.593 ** | ― | |||||||||

| [0.41,0.72] | [0.66,0.85] | [0.42,0.72] | |||||||||||

| 5. ADHD-IM | 0.462 ** | 0.704 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.514 ** | ― | ||||||||

| [0.26,63] | [0.57,0.80] | [0.44,0.73] | [0.32,0.67] | ||||||||||

| 6. ADHD-SL | 0.318 ** | 0.609 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.263 * | 0.299 ** | ― | |||||||

| [0.09,0.51] | [0.44,0.74] | [13,0.54] | [0.04,0.47] | [0.07,0.50] | |||||||||

| 7. ADHD-PL | 0.446 ** | 0.739 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.597 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.437 ** | ― | ||||||

| [0.24,0.61] | [0.61,0.83] | [0.27,0.63] | [0.43,0.73] | [0.25,0.62] | [0.23,0.61] | ||||||||

| 8. ADHD-CL | 0.572 ** | 0.812 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.537 ** | 0.499 ** | 0.409 ** | 0.595 ** | ― | |||||

| [0.39,0.71] | [0.72,0.88] | [0.41,0.72] | [0.35,0.68] | [0.30,0.65] | [0.20,0.58] | [0.42,0.73] | |||||||

| 9. ASD-TS | 0.443 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.408 ** | 0.279 * | 0.556 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.195 | 0.545 ** | ― | ||||

| [0.24,0.61] | [0.31,0.66] | [0.20,0.58] | [0.05,0.48] | [0.37,0.70] | [0.09,0.51] | [−0.04,0.41] | [0.36,0.69] | ||||||

| 10. ASD-AU | 0.481 ** | 0.625 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.379 ** | 0.610 ** | 0.411 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.588 ** | 0.903 ** | ― | |||

| [0.28,0.64] | [0.46,0.75] | [0.27,0.63] | [0.16,0.56] | [0.44,0.74] | [0.20,0.59] | [0.12,0.53] | [0.41,0.72] | [0.85,0.94] | |||||

| 11. ASD-INT | 0.283 * | 0.286 * | 0.298 ** | 0.126 | 0.416 ** | 0.154 | 0.045 | 0.395 ** | 0.876 ** | 0.614 ** | ― | ||

| [0.06,0.48] | [0.06,0.48] | [0.07,0.49] | [−0.11,0.35] | [0.20,0.59] | [−0.08,0.37] | [−0.19,0.27] | [0.18,0.57] | [0.81,0.92] | [0.45,0.74] | ||||

| 12. LDSPt7-TS | 0.508 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.308 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.054 | 0.141 | 0.527 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.434 ** | 0.331 ** | ― | |

| [0.31,0.66] | [0.18,0.57] | [0.11,0.53] | [0.08,0.50] | [0.19,0.58] | [−0.18,0.28] | [−0.09,0.36] | [0.34,0.68] | [0.21,0.60] | [0.23,0.60] | [0.11,0.52] | |||

| 13. SCLD10-TS | 0.514 ** | 0.392 ** | 0.312 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.035 | 0.240 * | 0.494 ** | 0.364 ** | 0.341 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.659 ** | ― |

| [0.32,0.67] | [0.18,0.57] | [0.09,0.51] | [0.20,0.59] | [0.10,0.51] | [−0.20,0.26] | [0.01,0.45] | [0.30,0.65] | [0.15,0.55] | [0.12,0.53] | [0.13,0.53] | [0.51,0.77] |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AAC-Q-TS | ― | ||||||||||||

| 2. ADHD-TS | 0.857 ** | ― | |||||||||||

| [0.48,0.97] | |||||||||||||

| 3. ADHD-CO | 0.784 * | 0.888 ** | ― | ||||||||||

| [0.28,0.95] | [0.57,0.97] | ||||||||||||

| 4. ADHD-INA | 0.505 | 0.728 * | 0.470 | ― | |||||||||

| [−0.20,0.87] | [0.16,0.93] | [−0.25,0.85] | |||||||||||

| 5. ADHD-IM | 0.728 * | 0.744 * | 0.755 * | 0.416 | ― | ||||||||

| [0.16,0.93] | [0.20,0.94] | [0.22,0.94] | [−0.31,0.84] | ||||||||||

| 6. ADHD-SL | 0.208 | 0.499 | 0.615 | 0.195 | 0.081 | ― | |||||||

| [−0.50,0.75] | [−0.21,0.86] | [−0.05,0.90] | [−0.51,0.74] | [−0.59,0.69] | |||||||||

| 7. ADHD-PL | 0.643 * | 0.768 ** | 0.668 * | 0.268 | 0.598 | 0.532 | ― | ||||||

| [0.00,0.91] | [0.25,0.94] | [0.04,0.92] | [−0.45,0.78] | [−0.07,0.90] | [−0.17,0.88] | ||||||||

| 8. ADHD-CL | 0.838 ** | 0.902 ** | 0.823 ** | 0.695 * | 0.655 * | 0.310 | 0.577 | ― | |||||

| [0.42,0.96] | [0.62,0.98] | [0.38,0.96] | [0.09,0.92] | [0.02,0.91] | [−0.42,0.79] | [−0.10,0.89] | |||||||

| 9. ASD-TS | 0.723 * | 0.710 * | 0.660 * | 0.527 | 0.712 * | 0.006 | 0.332 | 0.717 * | ― | ||||

| [0.15,0.93] | [0.12,0.93] | [0.03,0.91] | [−0.18,0.87] | [0.13,0.93] | [−0.64,0.65] | [−0.39,0.80] | [0.14,0.93] | ||||||

| 10. ASD-AU | 0.717 * | 0.704 * | 0.641 * | 0.577 | 0.681 * | 0.032 | 0.288 | 0.658 * | 0.978 ** | ― | |||

| [0.14,0.93] | [0.11,0.93] | [0.00,0.91] | [−0.10,0.89] | [0.07,0.92] | [−0.62,0.66] | [−0.43,0.79] | [0.03,0.91] | [0.90,10.0] | |||||

| 11. ASD-INT | 0.606 | 0.572 | 0.567 | 0.330 | 0.760 * | −0.146 | 0.277 | 0.643 * | 0.905 ** | 0.831 ** | ― | ||

| [0.06,0.90] | [−0.11,0.89] | [−0.12,0.89] | [−0.40,0.80] | [0.23,0.94] | [−0.72,0.55] | [−0.45,0.78] | [0.00,0.91] | [0.63,0.98] | [0.41,0.96] | ||||

| 12. LDSPt7-TS | 0.148 | 0.265 | 0.208 | −0.378 | 0.251 | −0.729 * | −0.279 | −0.155 | 0.222 | 0.189 | 0.433 | ― | |

| [−0.55,0.72] | [−0.78,0.45] | [−0.75,0.50] | [−0.82,0.35] | [−0.47,0.77] | [−0.93,0.16] | [−0.78,0.44] | [−0.73,0.54] | [−0.49,0.76] | [−0.52,0.74] | [−0.29,0.84] | |||

| 13. SCLD10-TS | 0.270 | 0.298 | 0.233 | 0.003 | −0.200 | −0.140 | −0.363 | −0.401 | −0.138 | −0.025 | −0.403 | −0.127 | ― |

| [−0.78,0.45] | [−0.79,0.43] | [−0.76,0.48] | [−0.64,0.64] | [−0.75,0.51] | [−0.72,0.55] | [−0.82,0.36] | [−0.83,0.33] | [−0.72,0.55] | [−0.66,0.63] | [−0.83,0.32] | [−0.71,0.56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yasunaga, M.; Higuchi, R.; Kusunoki, K.; Mori, C.; Mochizuki, N. Associations Between DCD Traits, Perceived Difficulties Related to ADHD, ASD, and Reading and Writing Support Needs Among Students in Higher Education: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14111083

Yasunaga M, Higuchi R, Kusunoki K, Mori C, Mochizuki N. Associations Between DCD Traits, Perceived Difficulties Related to ADHD, ASD, and Reading and Writing Support Needs Among Students in Higher Education: A Pilot Study. Brain Sciences. 2024; 14(11):1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14111083

Chicago/Turabian StyleYasunaga, Masanori, Ryutaro Higuchi, Keita Kusunoki, Chinatsu Mori, and Naoto Mochizuki. 2024. "Associations Between DCD Traits, Perceived Difficulties Related to ADHD, ASD, and Reading and Writing Support Needs Among Students in Higher Education: A Pilot Study" Brain Sciences 14, no. 11: 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14111083

APA StyleYasunaga, M., Higuchi, R., Kusunoki, K., Mori, C., & Mochizuki, N. (2024). Associations Between DCD Traits, Perceived Difficulties Related to ADHD, ASD, and Reading and Writing Support Needs Among Students in Higher Education: A Pilot Study. Brain Sciences, 14(11), 1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci14111083