Abstract

Background/Objectives: Pain memory refers to the ability to encode, store, and recall information related to a specific pain event. Reviewing its common features is crucial, as it provides researchers with a foundational guide for designing studies that assess pain memory in individuals with chronic pain. The primary objective of this study was to examine the common characteristics—particularly the methodological approaches—of existing research on pain memory in adults with chronic pain. Methods: A scoping review was conducted using PubMed and Embase as search databases. Studies were included if they met the following criteria. (a) It involved only adults with chronic pain and (b) assessed at least one of the following parameters: pain intensity or pain unpleasantness. The exclusion criteria were the following: (a) not having pain memory assessment as a primary objective, (b) including participants under 18 years of age, (c) involving individuals without chronic pain (e.g., those with acute pain or healthy participants), (d) lacking essential information, or (e) unavailability of the full text. Results: From an initial pool of 4585 papers, 11 studies met the inclusion criteria. All studies exclusively involved adults with chronic pain, and all reported pain intensity, while only 27% assessed pain unpleasantness. Additionally, psychosocial variables were the most frequently reported non-pain-related outcomes. Regarding study protocols, most relied on daily data collection, with the most common recall period being within the first 48 h. Conclusions: The methodological characteristics identified in this review—particularly those with a high frequency of occurrence—should serve as fundamental guidelines for future research on pain memory in adults with chronic pain, and should be carefully considered by investigators in this field.

1. Introduction

Pain memory refers to the ability to encode, store, and retrieve information related to a specific painful experience [1,2]. In terms of its processing, research has shown that working memory plays a key role in the short-term storage of pain-related information [3]. The recall of this short-term memory is influenced by the primary somatosensory cortex and the anterior insula [4]. Over time, this memory undergoes consolidation, transitioning from short-term to long-term storage, a process typically completed within 24 h and influenced by various factors [5]. Pain memory is known to contribute to the chronic progression of pain [6]. In particular, the interplay between the prefrontal cortex and limbic circuits plays a crucial role in pain chronicity [7]. Some researchers have even suggested that chronic pain may, in part, result from the inability to erase the memory trace of an initial injury [8]. Additionally, pain memory can shape future pain experiences and influence a patient’s decisions regarding potentially painful situations, including certain medical procedures, making it a critical consideration in chronic pain management [9]. Chronic pain has also been found to impair cognitive functions such as memory and attention [10,11]. One of the main challenges in this field is the inconsistency in findings regarding the accuracy and reliability of pain memory in chronic pain patients. While some studies indicate that pain memory is accurate [12,13], others suggest that patients tend to remember pain as more intense than it was originally experienced [14,15]. This discrepancy may stem from several factors known to influence pain memory [16], including age [17], average pain intensity [18], the time elapsed between the pain experience and its recall [13,19], expected pain [20,21], and psychological factors such as affect [22] and catastrophizing [23]. However, another critical issue is the considerable methodological heterogeneity in how pain memory is assessed. Given that pain memory assessment is conceptually simple, requiring only the experience of pain followed by a recall period, researchers have significant flexibility in designing their protocols. As a result, there is substantial variability in assessment procedures, further contributing to inconsistencies in the literature. Despite this, there has been little systematic analysis of the methods used to assess pain memory in chronic pain patients.

Objective and Research Question

To address this gap, the primary aim of this scoping review is to identify common methodological characteristics, particularly in the procedures used, across studies assessing pain memory in adults with chronic pain.

The research question guiding this review is as follows:

Despite the considerable methodological heterogeneity and the influence of various factors on pain memory, are there common characteristics—particularly in terms of procedures—across studies assessing pain memory in adults with chronic pain? If so, what are these characteristics?

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This study is a scoping review, conducted following PRISMA-ScR (Annex S1), which was carried out between September and November 2024.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search was conducted on 15 October 2024, and both a database search (using PubMed and Embase) and a manual search (through reference checking) were performed. No restrictions were applied regarding the year of publication. The terms, Boolean operators, and filters used are listed in Table 1. In addition, Annex S2 shows the search operations used in each of the databases.

Table 1.

Terms, Booleans operators, and filters used.

2.3. Study Selection

The inclusion criteria for the studies were as follows. (a) To include only adults with at least a diagnosis of chronic pain disorder or a history of pain for more than 3 months, and (b) to include the assessment and recall of at least one of the following parameters: pain intensity and pain unpleasantness. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were (a) not having the assessment of pain memory as a main objective, (b) including participants that do not have chronic pain (e.g., acute pain patients or healthy patients), (c) lacking key information, and (d) an inability to obtain the full text.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction was completed by one of the authors and verified by the second author. Previously, both authors discussed what information was relevant to be extracted from the studies. This key information was called “data items”. The “data items” selected after discussion between the two authors were the following: sample, association between studies, outcomes, characteristics of the intervention, and characteristics of the pain recall.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

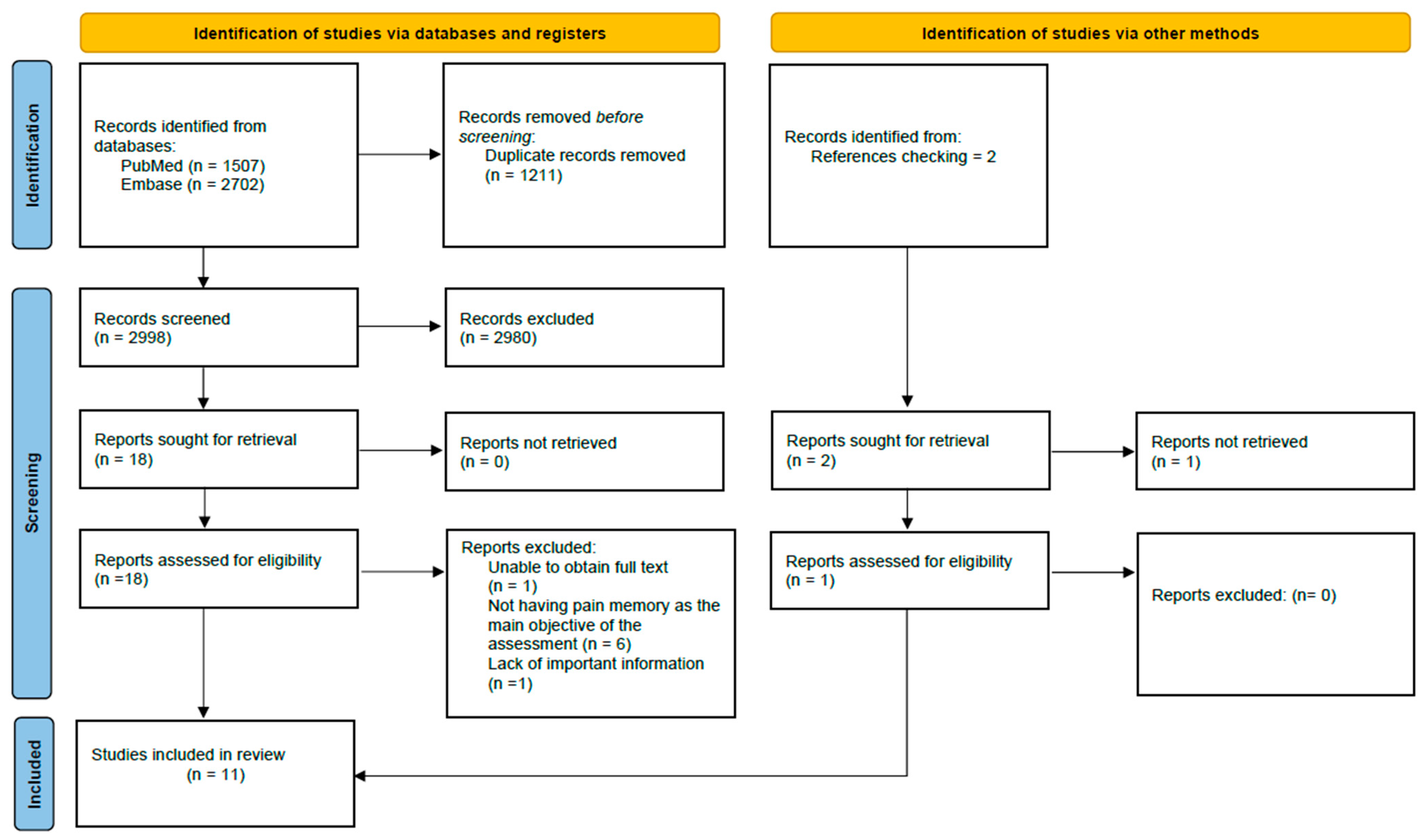

As for the results of the search, we first obtained 4209 articles, which after removing the duplicates, decreased to 2998. Once the studies were screened, the number of potential articles was 19. Finally, after a final review of potential articles, 11 studies were selected and included in the review. Details of the selection process for the included studies can be found in Figure 1. Furthermore, Table 2 details the characteristics of the 11 studies included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the selection of studies according to the PRISMA declaration.

Table 2.

The characteristics of the 11 studies.

3.2. Data Items Results

3.2.1. Sample

As for the sample included in this review, it is worth noting that the average number of participants is 55, with Jamison et al., 1989 [25], standing out as the study with the most participants (n = 93), and Linton and Melin 1982 [28] as the study with the fewest participants (n = 12). Due to the inclusion criteria established by this review, all studies included only adults with chronic pain, with a diverse range of diagnoses such as chronic musculoskeletal pain, headache, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis. Finally, regarding the gender of participants, in most studies the number of women was higher, with Linton 1991 [29] standing out as the only study that only included women.

3.2.2. Association Between Studies

It is important to mention the existence of an association between some of the included studies. Stone et al., 2004 [32], Stone et al., 2005 [33], and Raselli and Broderick, 2007 [31], are studies that share the same recruitment period and most of the procedures used as they come from the same basic research (Stone et al., 2003 [35]).

3.2.3. Outcomes

Regarding the outcomes used by the studies, a distinction must be made between two types of outcomes: those that serve to directly assess pain memory (pain memory outcomes) and those that do not (other outcomes). The current literature classifies both the unpleasantness of pain and the intensity of pain as pain memory outcomes [36,37]. Of the two outcomes, the one most used by the studies included in this review was pain intensity. In addition, it should be noted that the visual analog scale was the pain scale most used by the studies included to assess the pain memory outcomes (72%).

As for the other outcomes (non-pain memory outcomes) included in the studies, we mainly highlight those that have been found to affect pain memory, such as the current pain during the recall [38], anxiety [39], depressive symptoms [27], and catastrophism [23]. Furthermore, we have divided these results into three subgroups. The first group includes pain-related variables, such as current pain or qualitative dimensions of pain. The second group contains psychosocial variables, e.g., depression, anxiety, or catastrophizing. Finally, the last group includes all other variables.

3.2.4. Characteristics of the Interventions

In terms of the interventions, it is worth noting firstly that all the articles included had within their primary objective the aim to assess pain memory. Within the procedures found, there are two main trends. On the one hand, there are several articles that focus the assessment of pain memory on the application of a specific treatment. In most of these articles, the outcomes related to pain memory included (either pain intensity and/or pain unpleasantness) only had a single baseline measure, except for Smith and Safer, 1993 [34], which used the different pain intensities of the week prior to treatment collected daily using a pain diary as a baseline measure. In addition, the investigations that included specific treatment tended to take baseline measures of pain intensity prior to treatment, except for Porzelius et al., 1995 [30], which obtained the pain intensity score, which was later to be recalled, just after the treatment took effect. On the other hand, a significant number of studies focused on measuring outcomes related to pain memory daily during a specific period to recall them later. Most of these articles base their procedure on the use of what is known as a ‘pain diary’, which can be paper-based or electronic. Use of the pain diary varied according to the study, ranging from 7 to 30 days of use. Finally, there are studies that combine both approaches, as is the case of Smith and Safer, 1993 [34], which uses daily data collection using an electronic diary as a pre-treatment measure.

3.2.5. Characteristics of the Pain Recall

Finally, regarding pain recall, it should be noted that only the recall of pain intensity or unpleasantness of pain was counted, as it is only these parameters that are considered within pain memory [36,37]. Normally, pain recall was carried out with the same scale used in the baseline, although there are exceptions, among which we highlight the use of the original pain recall assessment (OPRA) form [26,27]. As to the timing of the recall, all the studies performed at least a single recall at the end of the treatment or the intervention. In addition, there are studies that also had an extra recall period in the middle of the assessment process (27%). As far as the recall time is concerned, it should be mentioned that it was the time since the last measure included in the recall, which in many cases coincided with the end of the intervention. The longest recall time was achieved by Linton, 1991 [29], in which pain recall took place 18 months after the noted painful experience. It is worth mentioning that the most common recall time was between just after evaluating the latest measurement included in the recall and two days after (first 48 h), with seven studies included in this period.

3.2.6. Summary of Findings

Firstly, due to the criteria of the study selection process, all papers included only adults with chronic pain. As for the variables used to assess pain memory, pain intensity was reported in all papers, while pain unpleasantness was reported in only 27%. On the other hand, psychosocial variables were the variables not related to pain memory that were most present (82%). Regarding the interventions, more interventions focused on daily collection data than on a specific treatment. Finally, in terms of recall, the most common recall time was during the first 2 days. Table 3 shows a representation of the number of studies in which each key characteristic appears.

Table 3.

Key features of each study presentation.

4. Discussion

The primary aim of this scoping review was to identify the common features, particularly in terms of methodological procedures, among studies assessing pain memory in adults with chronic pain. Based on our findings, the research question can be answered as follows: there are indeed common characteristics among the studies included. These key features are the following:

- The sample consists exclusively of adults with chronic pain.

- Pain memory assessment is a primary objective of the study.

- The evaluation and recall of pain intensity and/or pain unpleasantness are pain memory outcomes.

- The studies follow one of two methodological approaches: assessing pain memory in the context of a specific treatment, or assessing pain memory using daily measures.

Among these, the first characteristic—the exclusive focus on adults with chronic pain—is a direct consequence of the inclusion criteria applied in this review. While this was methodologically influenced by our selection process, it remains a crucial aspect, as it defines the population under study. However, it is worth noting that the broader literature on pain memory is not limited to adults with chronic pain; studies have also explored pain memory in children with chronic pain, patients with acute pain, and even healthy individuals [12,40,41].

The second characteristic, related to the primary objective of the studies, was also influenced by our scoping methodology. While our review included only studies where pain memory was a primary research focus, there are numerous studies where pain memory is assessed as a secondary or indirect outcome. The major limitation of such indirect assessments is that they often fail to evaluate both the pain experienced and its recall. This omission makes it impossible to determine the accuracy and consistency of pain memory. For instance, Jensen et al. [42] indirectly assessed pain memory by measuring recalled pain over the previous seven days, but did not include a corresponding measure of actual pain during that period. This type of methodological limitation is common in the literature and highlights the need for careful study design when investigating pain memory.

Regarding the third characteristic, although pain intensity and unpleasantness are the primary pain memory outcomes [36,37], some studies also assess additional recall measures, such as perceived changes in pain [31], or even non-pain-related outcomes, such as fatigue [43]. This variability underscores the importance of clearly distinguishing which parameters genuinely reflect pain memory.

The fourth characteristic, related to methodological approaches, highlights two dominant frameworks in the literature. The first approach assesses pain memory within the context of a specific treatment, typically using pre- and post-treatment measurements. This method is commonly employed in clinical trials evaluating treatment efficacy. The second approach focuses on continuous pain monitoring, often through daily pain diaries, which track fluctuations in pain over time [44]. One advantage of pain diaries is their sensitivity to day-to-day variations in pain intensity, which may reduce memory-related distortions compared to retrospective patient interviews [45].

4.1. Recall Characteristics and Methodological Challenges

One notable finding of this review is the lack of consistency in recall-related methodological aspects across studies. Consequently, it was not possible to identify a common recall feature. However, the existing literature provides valuable insights into factors influencing recall. One key aspect is the time interval between pain experience and recall. While some studies indicate that longer recall periods influence pain memory [13,19], others report no significant effect [46,47]. Additionally, Logan and Gedney’s model [48] suggests that certain psychological factors may exert a greater influence on pain memory depending on the recall time. Although this model primarily focuses on acute pain memory, it may also have implications for chronic pain research.

The considerable methodological heterogeneity observed in this review may impact on the validity of findings in pain memory research. Standardizing methodological approaches could improve study comparability and the overall reliability of the results. Future studies should strive to implement more homogeneous procedures, using insights from this review as a reference.

4.2. Research Implications

The main implication of this review stems from the identification of common methodological features in pain memory studies involving adults with chronic pain. These findings can serve as a framework for researchers designing studies in this field, helping to establish structured and replicable research protocols.

Additionally, one of the most significant observations is the disparity in the use of pain intensity and pain unpleasantness as pain memory outcomes. Pain intensity is far more frequently assessed than pain unpleasantness, yet it remains unclear which of these variables provides a more accurate representation of pain memory. Until further research clarifies this issue, it is advisable to include both measures rather than focusing predominantly on pain intensity, as seen in most studies included in this review.

4.3. Limitations

This scoping review includes several limitations which may contribute to the existence of error bias. Firstly, there is a lack of inclusion of data that may be key to discussing the characteristics of the studies included, such as the type of study or the percentage of dropouts. Secondly, this scoping review includes only studies in which all participants have chronic pain, which may be considered a limitation, as there are studies on pain memory that include both chronic pain patients and other types of patients (acute pain patients or healthy patients). Furthermore, it would be valuable to extend the research to the pediatric population in future studies. Thirdly, most of the articles included have a small sample size, which may be considered a limitation. Additionally, there are various methods of pain assessment beyond pain intensity and pain unpleasantness. It is important to note that this review was limited to evaluating these aspects using less objective criteria, such as the VAS and NRS, which may be considered a limitation. Consequently, future research should focus on exploring more objective methods of pain assessment. Finally, this study limits the analysis of pain memory to only adults, so it is recommended that future research uses an approach that also includes children, as similar studies exist in this population.

5. Conclusions

The studies included in this scoping review reveal a high degree of heterogeneity in the assessment of pain memory. However, some consistent characteristics have been identified. Given these findings, we suggest that the most frequently occurring characteristics identified in this review should serve as fundamental components of future pain memory protocols in adults with chronic pain. Standardizing these elements could enhance methodological consistency and improve the comparability of results in this field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci15030308/s1, Annex S1: PRISMA-ScR; Annex S2: Detailed search operations. Reference [49] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology and data curation, all authors; formal analysis, all authors; interpretation of results, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, F.C.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Squire, L.R. Memory and brain systems: 1969–2009. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 12711–12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merskey, H. Pain, learning and memory. J. Psychosom. Res. 1975, 19, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. Working memory. Science 1992, 255, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, M.C.; Duerden, E.G.; Rainville, P.; Duncan, G.H. Memory traces of pain in human cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 4612–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantsch, H.H.F.; Gawlitza, M.; Geber, C.; Baumgärtner, U.; Krämer, H.H.; Magerl, W.; Treede, R.D.; Birklein, F. Explicit episodic memory for sensory-discriminative components of capsaicin-induced pain: Immediate and delayed ratings. Pain 2009, 143, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasmuth, T.; Von Smitten, K.; Hietanen, P.; Kataja, M.; Kalso, E. Pain and other symptoms after different treatment modalities of breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 1995, 6, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.R.; Farmer, M.A.; Baliki, M.N.; Apkarian, A.V. Chronic pain: The role of learning and brain plasticity. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2014, 32, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apkarian, A.V. Pain perception in relation to emotional learning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2008, 18, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Schreiber, C.A.; Redelmeier, D.A. When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 4, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, B.D.; Rashiq, S. Disruption of attention and working memory traces in individuals with chronic pain. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 104, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderfjell, S. Musculoskeletal Pain, Memory, and Aging: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Findings. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- La Touche, R.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Suso-Martí, L.; Martín-Alcocer, N.; Mercado, F.; Cuenca-Martínez, F. Pain memory in patients with chronic pain versus asymptomatic individuals: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1741–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcgorry, R.W.; Webster, B.S.; Snook, S.H.; Hsiang1, S.M. Accuracy of Pain Recall in Chronic and Recurrent Low Back Pain. J. Occup. Rehabil. 1999, 9, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, S.; Salkovskis, P.M.; Jack, T. An experimental study of attention, labelling and memory in people suffering from chronic pain. Pain 2001, 94, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoth, D.E.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Liossi, C. A systematic review with subset meta-analysis of studies exploring memory recall biases for pain-related information in adults with chronic pain. Pain Rep. 2020, 5, e816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, M.; Ceci, S.J.; Francoeur, E.; Barr, R. “I Hardly Cried When I Got My Shot!” Influencing Children’s Reports about a Visit to. Child Dev. 1995, 66, 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brink, M.; Bandell-Hoekstra, E.N.; Abu-Saad, H.H. The occurrence of recall bias in pediatric headache: A comparison of questionnaire and diary data. Headache 2001, 41, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, Y.; Koyama, T.; Kroncke, A.P.; Coghill, R.C. Effects of stimulus duration on heat induced pain: The relationship between real-time and post-stimulus pain ratings. Pain 2004, 107, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feine, J.S.; Lavigne, G.J.; Dao, T.T.T.; Morin, C.; Lund, J.P. Memories of chronic pain and perceptions of relief. Pain 1998, 77, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavaruzzi, T.; Carnaghi, A.; Lotto, L.; Rumiati, R.; Meggiato, T.; Polato, F.; De Lazzari, F. Recalling pain experienced during a colonoscopy: Pain expectation and variability. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, L.Y.; Wager, T.D. How expectations shape pain. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 520, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anunciação, L.; Portugal, A.C.; Landeira-Fernandez, J.; Bajcar, E.A.; Bąbel, P. The Lighter Side of Pain: Do Positive Affective States Predict Memory of Pain Induced by Running a Marathon? J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peerdeman, K.J.; van Laarhoven, A.I.M.; Peters, M.L.; Evers, A.W.M. An integrative review of the influence of expectancies on pain. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, R.A. Memory for pain and affect in chronic pain patients. Pain 1993, 54, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, R.N.; Sbrocco, T.; Parris, W.C.V. The influence of physical and psychosocial factors on accuracy of memory for pain in chronic pain patients. Pain 1989, 37, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, J.C.; Keefe, F.J. Memory for pain: The relationship of pain catastrophizing to the recall of daily rheumatoid arthritis pain. Clin. J. Pain 2002, 18, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, J.C.; Keefe, F.J. The effect of neuroticism on the recall of persistent low-back pain and perceived activity interference. J. Pain 2013, 14, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J.; Melin, L. The accuracy of remembering chronic pain. Pain 1982, 13, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J. Memory for chronic pain intensity: Correlates of accuracy. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1991, 72 Pt 2, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porzelius, J. Memory for pain after nerve-block injections. Clin. J. Pain 1995, 11, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raselli, C.; Broderick, J.E. The association of depression and neuroticism with pain reports: A comparison of momentary and recalled pain assessment. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 62, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.A.; Broderick, J.E.; Shiffman, S.S.; Schwartz, J.E. Understanding recall of weekly pain from a momentary assessment perspective: Absolute agreement, between- and within-person consistency, and judged change in weekly pain. Pain 2004, 107, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.A.; Schwartz, J.E.; Broderick, J.E.; Shiffman, S.S. Variability of momentary pain predicts recall of weekly pain: A consequence of the peak (or salience) memory heuristic. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, W.B.; Safer, M.A. Effects of present pain level on recall of chronic pain and medication use. Pain 1993, 55, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.A.; Broderick, J.E.; Schwartz, J.E.; Shiffman, S.; Litcher-Kelly, L.; Calvanese, P. Intensive momentary reporting of pain with an electronic diary: Reactivity, compliance, and patient satisfaction. Pain 2003, 104, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajcar, E.A.; Swędzioł, W.; Wrześniewski, K.; Blecharz, J.; Bąbel, P. The Effects of Pain Expectancy and Desire for Pain Relief on the Memory of Pain in Half Trail Marathon Runners. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedney, J.J.; Logan, H.; Baron, R.S. Predictors of short-term and long-term memory of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. J. Pain 2003, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąbel, P.; Bajcar, E.A.; Śmieja, M.; Adamczyk, W.; Świder, K.; Kicman, P.; Lisińska, N. Pain begets pain. When marathon runners are not in pain anymore, they underestimate their memory of marathon pain––A mediation analysis. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G. Memory of dental pain. Pain 1985, 21, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, A.; Noel, M.; Van Ryckeghem, D.M.L.; Soltani, S.; Vervoort, T. The Moderating Role of Attention Control in the Relationship Between Pain Catastrophizing and Negatively-Biased Pain Memories in Youth with Chronic Pain. J. Pain 2021, 22, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M.; Nyiendo, J.; Aickin, M. One-year trend in pain and disability relief recall in acute and chronic ambulatory low back pain patients. Pain 2002, 95, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Tomé-Pires, C.; Solé, E.; Racine, M.; Castarlenas, E.; de la Vega, R.; Miró, J. Assessment of pain intensity in clinical trials: Individual ratings vs composite scores. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderick, J.E.; Schwartz, J.E.; Vikingstad, G.; Pribbernow, M.; Grossman, S.; Stone, A.A. The accuracy of pain and fatigue items across different reporting periods. Pain 2008, 139, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, O.B. Was leisten Schmerztagebücher? Vorzüge und Grenzen ihrer Anwendung unter besonderer Berücksichtigung einzelfallbezogener Auswertung. Schmerz 1995, 9, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wit, R.; van Dam, F.; Hanneman, M.; Zandbelt, L.; van Buuren, A.; van der Heijden, K.; Leenhouts, G.; Loonstra, S.; Abu-Saad, H.H. Evaluation of the use of a pain diary in chronic cancer pain patients at home. Pain 1999, 79, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąbel, P. Memory of pain and affect associated with migraine and non-migraine headaches. Memory 2015, 23, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąbel, P.; Krzemień, M. Memory of dental pain induced by tooth restoration. Stud Psychol. 2015, 53, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gedney, J.J.; Logan, H. Memory for stress-associated acute pain. J. Pain 2004, 5, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).