Abstract

The science of early childhood development underscores that maltreatment and other adversities experienced during infancy heightens the risk for poor developmental and socio-emotional outcomes. Referrals to supportive services by the child welfare system are particularly critical during infancy given the rapidity of brain development and infants’ sensitivity to their environment. The main objectives of the current study are to: (1) examine age-specific differences in clinical and case characteristics; (2) determine the factors associated with the service referral decision involving infants; and (3) explore the types of services families have been referred to at the conclusion of a maltreatment-related investigation. Using data from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect for 2013, descriptive analyses were conducted, as was a logistic regression to identify factors associated with the decision to refer families of infants to supportive services. Overall, the findings reveal that the profile of infants and their families differs distinctly from those of older children with respect to risks, service needs, and service referrals, although this is rarely reflected in child welfare practice and policy. Investigations involving infants were most likely to have a referral made to supportive services, least likely to have an infant functioning concern identified; most likely to have a primary caregiver risk factor identified; and, the greatest likelihood of experiencing economic hardship. Multiple risks, identified for the primary caregiver of the infant are correlated to referral decisions for infants. However, the needs of the infant are likely under-identified and require cross-sectorial collaboration.

1. Introduction

Children and families investigated by the child welfare system often have complex needs that may require various types of supportive services that span across numerous sectors [1,2,3,4]. The decision to refer children and families to supportive services can signal the child welfare systems’ recognition of child and/or family need [5]. A child welfare worker’s decision to refer to services is predicated upon the assessment of need. Identifying child and family needs and aligning services with those needs may help to prevent deterioration in family functioning, decrease the risk of maltreatment and increase the likelihood of family reunification [4,6,7]. Service referrals are an important step in promoting both the safety and well-being of children and can be particularly consequential for infants and young children. Early identification, referral, and intervention may buffer or prevent the developmental consequences of maltreatment and other adversities. Without appropriate intervention, developmental difficulties that emerge in early childhood can become more challenging to address and ameliorate over time [8]. Early identification and intervention are critical as the brain is most receptive to the environment in the first years of life [9]. Yet, there is minimal literature focusing on service referrals within the context of child welfare service provision [10]. There is little understanding of the types of services that children and families are referred to, including referrals to concrete services that may assist families in meeting their basic needs (e.g., food, housing, utilities), educational services (e.g., parent support groups), and clinical services (e.g., mental health counseling) [1,10]. There is no study that has explored the factors associated with the decision to provide service referrals to families of infants; nor, is there a study that has explored the types of services that families of infants and older children are referred to within the context of maltreatment-related investigations in Canada.

1.1. Developmental Issues for Infants

A high rate of developmental concerns has been found in infants and toddlers regardless of whether allegations were substantiated or unsubstantiated [11,12]. Children who remain in the home have shown similar high rates of mental health issues as children placed into out-of-home care [13,14]. For infants and young children involved with the child welfare system, there is a significant gap between the identification of need for mental services and service receipt [14]. Child welfare-involved infants are unlikely to have their developmental and mental health needs met prior to school entry [15]. Infants reported to and investigated by the Ontario child welfare system have been noted to be the least likely group of children to be identified by child welfare workers as having a functioning concern [16]. The lack of identification of developmental issues by the child welfare system can translate into low referral rates to, and underuse of, early intervention services [17,18]. There have been concerns about the adequacy of the child welfare system’s response to the unique needs of infants and young children throughout the extant literature [11,18,19,20,21,22,23].

1.2. Caregiver Concerns

Using the 2008 cycle of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS-2008), Jud, Fallon, and Trocmé found that caregiver risk factors (e.g., few social supports), younger caregiver age, and socio-economic hardship were significantly associated with the likelihood of receiving ongoing child welfare services or a referral to services post-investigation [24]. Palusci explored post-investigation services and recurrence after confirmed psychological maltreatment for children and found that poverty, drug, or alcohol issues and other forms of violence increased the likelihood of a service referral [25]. Less than one quarter of families were referred to services following confirmed psychological maltreatment.

Caregivers of children involved with the child welfare system have also been noted to experience unmet service needs [26,27]. In Ontario, being a victim of intimate partner violence (IPV), having few social support (i.e., social isolation or lack of social supports), and mental health issues have consistently emerged as the most frequently identified caregiver risk factors in maltreatment-related investigations involving infants [16,28]. Access to social supports from the community can help to buffer stress and reduce social isolation, a risk factor for both infant maltreatment and poor infant psychosocial functioning [29,30]. The importance of social supports in child welfare decision-making is highlighted by research indicating that a caregiver with few social supports is an influential predictor for transferring a case to ongoing child welfare services in two studies exploring maltreatment-related investigations involving infants and their families in Ontario [16,28]. A caregiver’s social support network is particularly consequential for infants as it can impact the quality of infant-caregiver relationship [30].

1.3. Factors Associated with Service Referrals and Dispositions

Child welfare workers have been described as service brokers and gateway providers to services for children and youth (e.g., [15,31,32]). A referral made by a child welfare worker for support services is a critical step to match services to needs [33]. The importance of understanding and addressing the needs of infants and young children who come into contact with the child welfare system is underscored by the accumulating evidence of their developmental vulnerabilities, unmet needs, and the underutilization of services [14,15,20]. Research suggests that initial involvement with the child welfare system may increase access to mental health services [15].

Despite the consequential nature of the service referral decision to the provision of services, child welfare decision-making research has primarily focused on the provision of ongoing child welfare services [16,24,28,34] and the decision to place children out-of-home [24,35,36,37]. The applicability and generalizability of the available extant service referral research to the Ontario child welfare context is limited by the lack of uniformity in several aspects of studies, including methodology, sample, variable type, definition of referral to services, the types of services referred to, the country of origin, and the broader policy and practice contexts. For example, Villigrana examined the factors that influence a referral to mental health services for child welfare-involved children by both court social workers and child welfare social workers in California by using case abstraction of closed court cases [38]. There were no significant predictors found for the decision to refer children to mental health services by child welfare social workers; however, significant predictors for mental health service referrals for court social workers have included the child remaining in their home and multiple types of abuse. Factors associated with service referrals have been found to differ by ethnicity [5]. For instance, a substantiation decision was more likely to result in a service referral for white families than for black families [5]. When compared to African American families, Hispanic families have been found to be more likely to be referred to psychosocial services than services that relate to basic needs, such as housing [10]. Amongst children with a developmental disability, a report of emotional maltreatment and out-of-home placement were two factors that increased the likelihood of a service referral for a formal assessment [39]. The likelihood of a referral to developmental services was more likely for cases in which the child welfare system had determined a need for services and where children experienced sexual abuse [40].There is a dearth of research that explores service referrals for infants and young children.

1.4. International Comparisons and Context

The majority of research exploring service referrals and/or utilization for child welfare-involved families originates from the United States, which has disparate policy, legislative, and practice contexts than Ontario, Canada. For instance, there are differences between the U.S. and Canada in how the knowledge of early childhood development has informed child welfare legislation and policies. In the U.S., amendments were made in 2003 to the Child Abuse and Prevention Act (CAPTA) in recognition of the importance of early intervention for young child welfare-involved children [11,40]. Funded under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA), states were required to develop referral procedures to early intervention services for children aged 0 to 3 years who were involved in a substantiated case of child maltreatment [11,40]. In 2011, the Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovations Act was introduced and this legislation required state reporting of activities involving young children in the child welfare system [41]. Moreover, in contrast to the U.S., child welfare in Canada is not governed by federal legislation, but legislation that is specific to each province and territory [42,43]. Ontario’s child welfare legislative mandate gives central and equal consideration to the notions of both protection and well-being [44]; however, there are no policies that address early intervention for infants and young children who come into contact with the child welfare system, nor is there mandated referral legislation. Although there is an existing policy orientation in support of differential response models, wide-scale programs have yet to be implemented in Ontario [16,45]. In contrast, several states in the U.S. have undergone Differential Response reforms, which emphasize family assessment, parental involvement, and needs-driven service [46]. In comparison to families that undergo investigations, families that are offered services through an assessment approach have been found to be provided with a greater array of services [46]. Child welfare service models in Canada are not yet aligned with emerging investigative trends that suggest greater focus on the long-term impact of family dysfunction than immediate safety concerns [44].

Findings from the research on Canadian incidence studies at both the provincial and national levels suggest that infants are a unique subgroup of children involved with the child welfare system [16,28,34,37]. The age of children influences the risk of maltreatment and how the child welfare system subsequently responds to it [23,25,47]. Investigations involving infants are most likely to result in intensive service responses, including greater likelihood of receiving ongoing child welfare services and out-of-home placements [37]. Key drivers of service provision decisions differ by age. Caregiver risk factors have been found to drive the decision to provide ongoing child welfare services [16,28,34] and out-of-home placements for infants [48]. In contrast, child functioning concerns are key contributors for both decisions involving older children and adolescents [36,37]. These findings underscore the importance of exploring the unique mix of child, family, and broader environmental risks, protective factors, and needs that may emerge around specific ages and developmental stages [47]. The composition of services required to support families with infants should differ from those required to support families with older children [47]. Palusci found that infants and young children (0–5 years of age) involved with the child welfare system experienced different risk factors and services than those of older children [49]. There is a dearth of research exploring types of services offered to families who have had involvement with the child welfare system [10].

1.5. Research Questions

The state of the literature suggests that the child welfare decision to refer families to services warrants more focused attention, particularly given the salience of this decision to infants and their families within a Canadian child welfare context. There is no study that has specifically examined the service referral decision for infants and families who have been investigated by the child welfare system; nor, has there been an age-specific exploration of the patterns and types of services families have been referred to in a Canadian context. An understanding of the clinical profile infants and their families, their needs, and the child welfare system’s response is critical to developing targeted, appropriate, and effective interventions. As a result of the significant gaps in the knowledge base, this exploratory study uses the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2013 (OIS-2013) [50] to answer the following questions:

- What are the characteristics (child, caregiver, household, case, and short-term service outcomes) of maltreatment-related investigations of children that are infants (less than 1) and do these characteristics differ when compared to other age groups, including, preschool aged (1–3), early school-aged (4–7), pre-adolescent (8–11), and adolescent (12–15) children investigated by the child welfare system across Ontario?

- Which characteristics are associated with the decision to refer infants and families for supportive services following maltreatment-related investigations?

- What are the types of supportive services that families of infants and older children are referred to?

The OIS is currently the only source of provincially aggregated child welfare data in Ontario. The OIS is also the only source of data that includes whether a child welfare worker made a referral for supportive services during the investigative period. The central objective of this study is to better understand the unique characteristics of infants and their families by exploring differences between infants and other age groups, and to build on the evolving research on factors related to service provision with this particularly vulnerable subpopulation of children. Understanding factors associated with child welfare service referral decisions for infants, and age-specific trends for the broader population of children, is important to strategically addressing and targeting child and family needs. This research provides a snapshot of the risk factors, child and family needs, and the supportive services that families are referred to at the conclusion of an initial child welfare investigation. Given the dearth of research on infants and the decision to provide service referrals within a Canadian child welfare context, this exploratory analysis is warranted and an important step for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

A secondary analysis of the 2013 cycle of the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (OIS) was conducted. The OIS-2013 is the fifth provincial study to examine provincial estimates of the incidence of reported child maltreatment and characteristics of the children and families investigated by the child protection system in Ontario. The OIS is a serial survey conducted with child welfare workers regarding their investigations of child maltreatment. The study is cross-sectional. The OIS utilizes a three-stage sampling design to select a representative sample of 17 child welfare agencies from a provincial list of 46 child welfare agencies [51]. Cases opened between 1 October 2013 and 31 December 2013 of the study cycle were eligible for inclusion in the study. Children not reported to child welfare services, screened out reports, and new allegations on open cases at the time of selection were not included in the OIS-2013. The three-month study period is considered optimal for participation and compliance with study procedures [51].

Maltreatment-related investigations included in the OIS-2013 are comprised of two types: (1) where there is no specific concern about past maltreatment but future risk of maltreatment is being assessed (risk-only); and (2) where maltreatment may have occurred. Maltreatment-related investigations, regardless of their substantiation status were included in this analysis. Children over 15 years of age, siblings not investigated, and children who were investigated for non-maltreatment concerns were excluded from the sample.

Child welfare cases in Ontario are counted as families. There were 3118 cases opened at the family-level during the 3-month period. The final stage of the sampling consisted of identifying investigated children as a result of maltreatment concerns. There were a total of 5265 children investigated as a result of the identification of maltreatment concerns. Of those 5265 children investigated, 345 were infants. The University of Toronto provided ethics approval (protocol number 28580).

2.2. Study Weights

Provincial estimates were derived by applying full weights, which includes both annualization and regionalization weights. These procedures yielded a final weighted sample of 125,281 children investigated because of maltreatment-related concerns. This study focused specifically on maltreatment-related investigations involving infants (under the age of 1 year) and explored factors associated with the decision to provide a referral for supportive services at the conclusion of the investigation. The final provincial estimate was 7915 investigations involving infants. For a detailed description of the OIS-2013 methodology and weighting procedures, please see Fallon and colleagues [51].

2.3. Data Collection Instrument

Data for the OIS-2013 is collected directly from investigating child welfare workers using a three-page standardized data collection instrument, the Maltreatment Assessment Form. This form is completed at the conclusion of the initial investigation. The OIS-2013 had an item completion rate of over 99% for all items. The instrument collected clinical information that child welfare workers routinely gather as part of their initial investigation, such as: caregiver, infant, case characteristics, and short-term service dispositions, including whether a referral for supportive services had been made, and the types of services referred to. Child welfare workers were asked to indicate whether any referrals for services had been made for any family member at the end of the investigation. If so, workers were asked to indicate all referrals that applied. These referrals include internal referrals to a special program provided by the child welfare organization or to other agencies or services external to the child welfare organization.

2.4. Variable Selection

The decision to refer to services is a dichotomous variable. The variable definitions and codes used in this analysis are provided in Table 1. Clinical variables were chosen on their availability in the dataset and on the literature addressing factors related to the occurrence of child maltreatment and the child welfare system’s response to infants.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and codes.

2.5. Analyitic Approach

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted in order to explore and compare the profile of investigations involving infants (under the age of 1) to children in older age groups, including preschool (1–3), and early school-age (4–7), pre-adolescent (8–11), and adolescent (12–15) children in Ontario in 2013. Provincial incidence estimates were calculated by dividing the weighted estimates by the child population based upon 2011 Census data from Statistics Canada. Chi-square tests of significance were conducted using the normalized sample weight, which adjusts for the inflation of the chi-square statistic by the size of the estimate by weighing the estimate down to the original sample size. As Table 2 shows, infants were compared to four other age groups and the p-value was subsequently adjusted as a result (0.05/4 comparisons = 0.013). Thus, all significance tests for chi-square analyses conducted and shown in Table 2 were evaluated using the adjusted p-value (p < 0.013), resulting from the Bonferroni correction given the four multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Prevalence and bivariate analyses of investigation characteristics by child age for maltreatment-related investigations in Ontario in 2013.

Multivariate analysis was conducted in order to explore which variables were significant with the decision to provide a service referral at the conclusion of maltreatment-related investigations involving infants. Prior to the logistic regression, bivariate chi-square analyses were conducted to explore associations between clinical and case characteristics and service referrals. Only variables that were significant at the bivariate level (p < 0.05) were included in the logistic regression model. Logistic regression was deemed an appropriate analysis strategy as the outcome variable is dichotomous and it can estimate the relationship between predictor variables with the likelihood or probability of an event occurring [52]. The cutoff point for the decision to refer to services was 0.57, which reflects the proportion of investigations referred for services for the infant population. This analysis did not include missing data in the bivariate or multivariate analysis. Unweighted data were used in the multivariate model to ensure unbiased results due to the inflation of significance due to a large sample size. All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

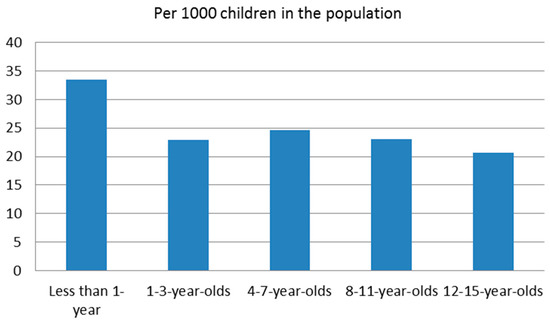

Numerous distinctions emerged in child, primary caregiver, household, maltreatment, case characteristics, and service outcomes between infants and older children investigated in Ontario in 2013 (Figure 1, Table 2). In comparison to all other age groups, maltreatment-related investigations involving infants had the highest incidence of a service referral at 33.50 per 1000; followed by early school-aged children at 24.69 per 1000; preadolescents at 23.07 per 1000 investigations; pre-schoolers at 22.93 per 1000; and adolescents at 20.66 per 1000 (Figure 1). Incidence rates suggest that investigations involving adolescents were the least likely to result in the decision to provide a service referral for any family member, with a rate of 20.66 per 1000.

Figure 1.

Incidence of a service referral for maltreatment-related investigations by child age.

3.1. Child Characteristics

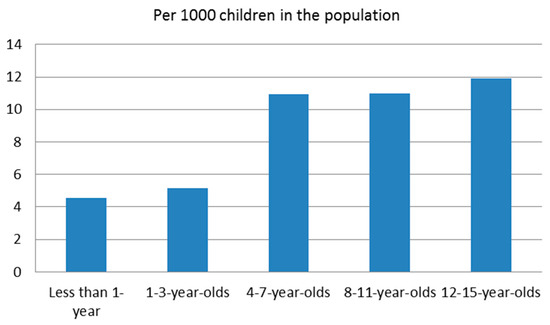

Descriptive and chi-square analyses revealed many differences between infants and the other four age groups (Table 2). The distribution of child characteristics, including sex and ethnicity are similar across the five different age groups (Table 2). The likelihood of a child welfare worker identifying a child functioning concern increased with age (Table 2 and Figure 2). Infants were significantly less likely to have a child functioning concern identified when compared to children who were early school-aged (4–7), pre-adolescent (8–11), and adolescent (12–15). Infants had the lowest incidence at a rate of 4.53 per 1000. In contrast, adolescents (12–15) had the highest incidence rate at 11.93 per 1000.

Figure 2.

Incidence of a child functioning concern in maltreatment-related investigations.

3.2. Primary Caregiver Characteristics and Risk Factors

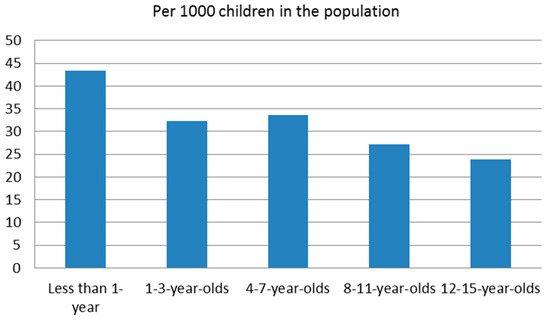

Infants had the highest incidence of caregivers identified as having at least one risk factor, with a rate of 43.44 per 1000 (Figure 3). Early school-aged children followed next with an incidence rate of 33.64 per 1000, preschoolers have an incidence rate of 32.33 per 1000, and preadolescents have an incident rate of 27.17 per 1000. Adolescents have the lowest incidence rate of caregivers identified with at least one caregiver risk factor at a rate of 23.78 per 1000.

Figure 3.

Incidence of a caregiver risk factor in maltreatment-related investigations in Ontario 2013.

Chi square tests (Table 2) revealed caregivers of infants were significantly more likely to be younger (21 years of age or under) than caregivers of children in each of the four older age groups. Caregivers of infants were also significantly more likely to be identified as having the following risk factors: drug solvent use, cognitive impairment, mental health issues, having a history of foster care, and having at least one caregiver risk factor identified. The three most common caregiver risk factors identified for caregivers of infants were being a victim of IPV, few social supports, and having a mental health issue (Table 2).

3.3. Household Characteristics

Infants were most frequently identified as living in households with at least one hazard, regularly running out of money, and moving two or more times. Chi-square analyses also indicated that infants were significantly more likely to be identified to be living in a household that regularly ran out of money for basic necessities than families of older children.

3.4. Maltreatment, Case Characteristics, and Short-Term Service Outcomes

When compared to all other age groups, infants were most likely to be involved in investigations where there was no specific incident of maltreatment alleged, but there was an allegation of future risk of maltreatment. Infants and pre-school aged children were most frequently investigated for exposure to IPV. Neglect was the most common type of investigated maltreatment, with minimal variation across age groups. Moreover, in comparison to each of the four older age groups, investigations involving infants were significantly more likely to result in court involvement and a transfer to ongoing child welfare services. With the exception of adolescents, investigations involving infants were significantly more likely to result in an out-of-home placement for all other age groups. Infants and adolescents were among the age groups with the highest prevalence of out-of-home placement post-investigation.

3.5. Characteristics Related with Service Referrals for Maltreatment-Related Investigations Involving Infants

Chi-square analyses were conducted in order to determine which child, caregiver, household, and case characteristics influenced the decision to provide a referral for maltreatment-related investigations involving infants. Table 3 shows the characteristics of maltreatment-related investigations involving infants and the eight variables that were significantly associated with the decision to provide referrals for supportive services: the identification of a child functioning issue, younger primary caregiver age, drug/solvent use; few social supports, at least one household hazard, regularly running out of money; and, greater number of moves. The eight variables found to be significant in relation to service referrals were then placed in the binary logistic regression model.

Table 3.

Referral-related characteristics in maltreatment-related investigations involving infants referred for services in Ontario in 2013.

3.6. Predictors of Service Referral for Maltreatment-Related Investigations Involving Infants: Logistic Regression Analysis

There were two primary caregiver characteristics that contributed to the prediction of a service referral for infants in the final model: being a victim of IPV and primary caregiver age. Thus, infants’ exposure to IPV and having a younger caregiver increased the likelihood of a service referral (Table 4). Having a caregiver who was a victim of IPV was the largest contributor to the decision to refer to specialized services. Having a primary caregiver aged 21 years or younger, in comparison to having a primary caregiver 22 years or older, more than doubled the odds of being referred for services (OR = 2.54, p < 0.01). The presence of IPV among primary caregivers increased the likelihood of a service referral being made by a factor of 2.81 (OR = 2.81, p < 0.01). The omnibus tests of model coefficients χ2 (8) = 39.24, p < 0.001 indicates that the model was significant. The model accounted for approximately 20.0% of the variance on the outcome (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.20).

Table 4.

Logistic regression model predicting service referrals for maltreatment-related investigations involving infants in Ontario in 2013.

3.7. Referral to Supportive Services

General areas for possible referrals to supportive services included: parenting and family support; addiction and mental health support; physical health; IPV, legal and victim support; income, food and housing support; cultural services; speech and language; and, recreational services. As Table 5 shows, interesting patterns emerged in the types of referrals provided by child welfare workers by age group. In comparison to all other age groups, families of infants were most commonly referred to a parent support group and in-home family or parenting counseling, and/or addiction counseling. Amongst families of infants, parenting and family support was the most common type of service referred to by child welfare workers.

Table 5.

Type of service referrals in maltreatment-related investigations by age group in Ontario in 2013.

Families with infants were most likely to receive a referral for drug or alcohol counseling; whereas families with adolescents were most likely to receive referrals for mental health. Overall, families of infants and preschool aged children were most likely to receive referrals for supports for meeting their basic needs, and included income, food, and housing supports. When compared to families of children in older age groups, families with younger children (i.e., infants and preschool aged children) were almost equally likely to be referred for IPV supports.

4. Discussion

Utilizing a Canadian provincial dataset, this study corroborates and extends the existing research. The findings highlight the distinct profile of infants and families investigated by the child welfare system. When comparing maltreatment-related investigations of infants to older children, numerous differences emerged with respect to risks, service needs, the child welfare system’s response, and the types of supportive services referred to by the child welfare system. The findings of this study also provide a broad understanding of the clinical factors that drive the decision to provide a referral to services for infants and their families. The majority of investigations involving infants received a service referral. When compared to older children, maltreatment-related investigations involving infants were significantly more likely to result in a referral for supportive services. These findings are indicative of the child welfare system’s recognition of the complex challenges families of infants are contending with and the importance and necessity of working with services in the community to address them. When comparing caregivers of infants to those of older children, caregivers of infants were significantly more likely to be identified as having at least one functioning issue. Maltreatment-related investigations involving infants were significantly more likely to have an investigating worker identify primary caregiver risk factors that include drug/solvent use, cognitive impairment, and a history of foster care. Alcohol abuse, drug/solvent use, cognitive impairments, mental health issues, few social supports, being a victim of IPV, and having a history of foster care were risk factors that were more common for caregivers of infants.

When compared to older children, infants were more likely to live in homes that regularly ran out of money for basic necessities, such as food, shelter, and utilities. These findings are consistent with research indicating that families with younger children tend to experience greater socio-economic hardships than older children [36,37]. This finding is concerning given that the literature suggests that low socio-economic status is linked to poor developmental outcomes for younger children as a result of its detrimental impact on the quality of the infant-caregiver relationship [53]. Poverty has also been identified as a risk factor for neglect [29]. This study found that neglect was the primary form of maltreatment alleged in approximately 1 in every 5 maltreatment-related investigations for each age group. The rapidity of brain development during infancy makes infants particularly susceptible to the profound and widespread developmental effects of neglect [29].

Infants were also significantly more likely to be investigated for reasons other than specific incidents of alleged maltreatment. Although the type of investigation (risk-only versus maltreatment) was not associated with the decision to provide a referral in this study, previous research suggests that risk-only investigations present with similar household and poverty-related concerns as maltreatment investigations [54]. This raises issues with respect to the operationalization of child welfare’s dual mandate of child safety and well-being for infants, particularly within the context of traditional service delivery models that emphasize protection. A child safety focus tends to prioritize the assessment of risk; whereas, a focus on well-being prioritizes the assessment of child and family needs [50]. Child welfare service decisions, including the decision to refer to services, should be based on a comprehensive assessment that includes consideration of both risk and needs [50]. This study corroborates previous research that suggests that infants and their families are the recipients of the child welfare system’s most intensive responses [37]. When compared to older children, infants were significantly more likely to be transferred to ongoing services and to be the subject of a court application. Both infants had the highest proportion of out-of-home placements, followed by adolescents. Previous research has found that infants are more likely than older children to be placed out-of-home [37]; however, it is important to note that the vast majority of infants in this study (over 90%) remained in the home following a maltreatment-related investigation. Commonly, infants who remain at home following alleged maltreatment experience high rates of re-reporting [55]. Research examining the re-reporting of infants and children following maltreatment-related investigations that considers the Ontario child welfare context is important to informing prevention and intervention efforts [56].

Two factors were significant in predicting the decision to refer to services and both were associated with the primary caregiver: being a victim of IPV and younger caregiver age. As in Jud, Fallon, and Trocmé’s study, the presence of IPV had a significant impact on the decision to refer to services [24]. Having a caregiver who was a victim of IPV was the most common caregiver risk factor identified by investigating child welfare workers for all age groups, with the exception of adolescents. In keeping with the findings of Fallon and colleagues, IPV exposure in this study was found to be the most commonly identified concern in maltreatment-related investigations involving infants in Ontario [16]. The finding that service referral decisions were also significantly associated with younger caregiver age is consistent with previous Canadian research [24] and the broader literature indicating that young caregiver age is a risk factor for maltreatment and is associated with the decision to provide ongoing services [16,28,34,57]. It is notable that many variables (e.g., child functioning concern, primary caregiver drug/solvent use, primary caregiver with few social supports) did not contribute to the decision to provide a service referral for infants. It appears that child welfare workers were most clinically concerned about the impact of IPV and younger caregiver age on caregiving skills and ability to meet infants’ needs. Previous research from Ontario conducted by Fallon and colleagues suggests that a differential systems response is required for IPV and this should depend on the type of exposure and the constellation of other risk factors at the child, family, and household levels [58]. Further research is required to better understand the child welfare response to IPV in a Canadian context [58].

The absence of association between caregiver mental health and service referral at the bivariate level is not in keeping with broader Canadian research on infants that has linked caregiver mental health to other service provision decisions, such as the decision to provide ongoing services [16,34], and the decision to place infants out-of-home [48]. Moreover, there is a well-established body of research that suggests that caregiver functioning issues, such as chronic depression, may act to compromise the quality of the infant-caregiver relationship and negatively impact short-term and long-term development [59]. Socio-economic hardship risk variables (e.g., running out of money for basic necessities, primary income, unsafe housing/household hazards) did not seemingly impact the likelihood of service referrals in this model. It may be that the measures informing socio-economic disadvantage are somewhat crude and socio-economic status is generally quite low for many families that come to the attention of the child welfare system in Ontario.

Disparities in the decision to provide and utilize services have been linked to child race and ethnicity [5,10,60]. In this study, child ethnicity was not significant at the bivariate level. This is in keeping with Jud, Fallon, and Trocmé’s study that found that ethnicity did not influence the decision to provide ongoing services or a referral for supportive services [24]. The role of child race in service referral decision-making is not well understood [5] Further research is needed to explore racial and ethnic disparities in service provision decisions, including the decision to refer to services regarding infants within a Canadian child welfare context.

In keeping with previous research [16], this study revealed that when compared to older children, infants in Ontario are less likely to be identified as having a child functioning issue. Although found to be significantly associated with service referrals at the bivariate level for infants, the identification of a child functioning concern did not predict a service referral in the multivariate model. The literature compellingly suggests that the mental health needs of infants and young children involved with the child welfare system are under-identified and untreated. Referral to appropriate services for families and children starts with the accurate identification of needs. There is no comprehensive or systematic developmental screening strategy in place in Ontario for infants involved with the child welfare system. Standardized, reliable, and valid measures may assist child welfare workers in the assessment and identification of need of early intervention services. There were age-specific differences in the types of services families were referred to by investigating child welfare workers. This study revealed that families of infants and young children (0–3 years old) were most commonly referred to services that relate to IPV and parenting/family support, such as support groups and/or counselling. Infants and younger children (ages 0–3 years) were also more commonly referred to income, food, and housing support services (e.g., social assistance, food bank, and shelter services) than older children. The importance of adopting a differential approach to child welfare policy, practice, and research that considers child age has been forwarded and is supported by the findings of this study [61]. Ontario has not yet implemented wide-scale programs with respect to differential response options [16,45]. Together with other studies, these findings lead to questioning whether an alternative or differential response approach with infants should be a consideration given their distinct clinical profile, risks, and need for supportive services.

In principle, service referrals should be primarily driven by case or clinical factors; however, child welfare service decisions are complex and can be influenced by factors at other levels, including worker, organizational, and the broader environment [62]. In addition, organization-level factors and regional variations have been found to influence the likelihood of service referrals [24]. The availability and accessibility of services may also be influencing child welfare workers’ decisions to refer to services to and the types of services are referred to. As such, both availability and accessibility may be influenced by geographic location, which may in turn influence the ability of families to utilize community services [63]. Location may be a proxy measure for several underlying organizational constructs, including differential access to resources and partnerships between social service agencies and child welfare organizations [64]. Differences in child welfare services and geographic location or jurisdiction have not been adequately addressed in the literature [64]. Thus, influences at the organizational and structural levels require further research, particularly with respect to maltreatment-related investigations involving infants [24].

In Ontario, infant and childhood mental health has been identified as, “… an issue that requires further policy development to ensure the availability and accessibility of optimal and consistent services across the province” (p. 5) [65]. To date, there is no provincial strategy that has focused on the mental health needs of infants and young children in Canada [65]. A key recommendation made for immediate policy development includes the provision of targeted supports to populations at-risk and working with an inter-generational intervention model [65]. Clinton and colleagues noted that infant-caregiver dyad is not the primary client focus in Ontario services, as infants and caregivers are treated as distinct entities [65].

Study Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that must be considered when interpreting the results. Data collected from the OIS is collected directly from the investigating child welfare worker and are not independently verified. The data is representative of an investigative period of thirty days after the case has opened. The study is cross-sectional and does not track longer-term service events that occurred beyond the initial investigation. The three-month sampling period is considered optimum to ensuring high participation rates and compliance with study procedures [51]. Consultations with service providers have indicated that case activity during the three-month period is reflective of the year; however, follow-up studies are needed to explore the extent of the possible impact of seasonal variation in types of cases reported on estimates [51]. The sample size of maltreatment-related investigations involving infants may have precluded some significant relationships from emerging. Types of services referred to were categorized broadly by family, not by child or caregiver, and provide a broad understanding of risk and needs. The OIS does not track specific referral actions or strategies used by child welfare workers (e.g., providing families with names and numbers, assisted caregiver with the referral). The OIS does not track whether services were received as a result of referral made by the worker during the investigative period. The OIS tracks whether a referral has been made and they type of services referred to. It is unknown whether families were engaged in other community services during this period. Moreover, the amount of variance explained by this model was small, with a large proportion of variance unaccounted for.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the minimal knowledge base relating to infants served by the child welfare system within a Canadian context. Despite the study limitations in tracking the progress of infants through the child welfare system, this study marks an important step to moving towards a better understanding of what investigations will effectively address the needs of vulnerable infants and their families. To date, the OIS is the only source of aggregated data in the province of Ontario and the findings are a reminder of the importance of provincial data in exploring and advocating for possible gaps in supports and resources for child-welfare involved children. Child welfare policy is set by the provincial government that also sets policies and funds for other allied sectors (e.g., children’s mental health) that are integral to effective service provision. Greater understanding of the factors associated with service referrals and the types of services referred to can assist in aligning, organizing, and targeting child welfare and community services to address the risks and needs of child-welfare involved children and families.

A referral for services can be viewed as a critical step to enhancing infants’ safety and well-being, and should be predicated upon the accurate identification of infant and family risks and needs. There are concerns that the child welfare system missing opportunities to identify, and thereby, ameliorate infants’ well-being given the extant literature and this study’s findings of low identification of infant functioning. Further research within a Canadian context is necessary in order to address these concerns. Moreover, adequately addressing infant well-being requires services that are accessible, available, and effective. As the findings suggest, infants are a distinctly vulnerable group of children involved with the child welfare system and require urgent and coherent attention at policy and practice levels within the field of child welfare and across multiple sectors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (#950-231186).

Author Contributions

B.F. is the Principal Investigator of the OIS-2013. J.F. synthesized the literature, conducted data analyses and interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and had input into the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Simon, J.D.; Brooks, D. Identifying families with complex needs after an initial child abuse investigation: A comparison of demographics and needs related to domestic violence, mental health, and substance use. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 67, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.D.; Brooks, D. Post-investigation service need and utilization among families at risk of maltreatment. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 69, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.E.K.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Heneghan, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Kerker, B.; Landsverk, J.; Horwitz, S.M. For Better or Worse? Change in Service Use by Children Investigated by Child Welfare Over a Decade. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, J.C.; Ryan, J.P.; Choi, S.; Testa, M.F. Integrated services for families with multiple problems: Obstacles to family reunification. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, S.A. Service referral patterns among black and white families involved with child protective services. J. Public Child Welf. 2013, 7, 370–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ryan, J.P. Co-occurring problems for substance abusing mothers in child welfare: Matching services to improve family reunification. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2007, 29, 1395–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.P.; Schuerman, J.R. Matching family problems with specific family preservation services: A study of service effectiveness. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2004, 26, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood; Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B.D. Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. J. Loss Trauma 2009, 14, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovato-Hermann, K.; Dellor, E.; Tam, C.C.; Curry, S.; Freisthler, B. Racial disparities in service referrals for families in the child welfare system. J. Public Child Welf. 2017, 11, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, J.S.; Cahalane, H.; Fusco, R.A. Directions for developmental screening in child welfare based on the ages and stages questionnaires. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1412–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanueva, C.E.; Cross, T.P.; Ringeisen, H. Developmental needs and individualized family service plans among infants and toddlers in the child welfare system. Child Maltreat. 2008, 13, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, B.J.; Phillips, S.D.; Wagner, H.R.; Barth, R.P.; Kolko, D.J.; Campbell, Y.; Landsverk, J. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCue Horwitz, S.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Heneghan, A.; Zhang, J.; Rolls-Reutz, J.; Fisher, E.; Landsverk, J.; Stein, R.E.K. Mental health problems in young children investigated by U.S. child welfare agencies. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 51, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringeisen, H.; Casanueva, C.; Cross, T.P.; Urato, M. Mental health and special education services at school entry for children who were involved with the child welfare system as infants. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2009, 17, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, B.; Ma, J.; Allan, K.; Trocmé, N.; Jud, A. Child maltreatment-related investigations involving infants: Opportunities for resilience? Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resielience 2013, 1, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Smith, R.; Schmitt, K. Implementing developmental screening programs for infants and toddlers in the child welfare system. J. Public Child Welf. 2014, 8, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.E.; Park, S.; Anaya, A.; Perugini, S.M.; Rao, S.; Neece, C.L.; Rafeedie, J. Linking infants and toddlers in foster care to early childhood mental health services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrick, J.D.; Needell, B.; Barth, R.P.; Jonson-Reid, M. Tender Years: Toward Developmentally Sensitive Child Welfare Services for very Young Children; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, S.M.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Heneghan, A.; Zhang, J.; Rolls-Reutz, J.; Landsverk, J.; Stein, R.E.K. Persistence of Mental Health Problems in Very Young Children Investigated by US Child Welfare Agencies. Acad. Pediatr. 2013, 13, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones Harden, B. Infants in the Child Welfare System: A Developmental Framework for Policy and Practice; Zero To Three: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-943657-97-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stahmer, A.C. Developmental and behavioral needs and service use for young children in child welfare. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulczyn, F.; Barth, R.P.; Ying-Ying, T.Y.; Jones Harden, B.; Landsverk, J. Beyond Common Sense : Child Welfare, Child Well-Being, and the Evidence for Policy Reform; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-202-30734-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jud, A.; Fallon, B.; Trocmé, N. Who gets services and who does not? Multi-level approach to the decision for ongoing child welfare or referral to specialized services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palusci, V.J.; Ondersma, S.J. Services and Recurrence After Psychological Maltreatment Confirmed by Child Protective Services. Child Maltreat. 2012, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, A.M.; Orton, H.D.; Barth, R.P.; Webb, M.B.; Burns, B.J.; Wood, P.; Spicer, P. Alcohol, drug, and mental health specialty treatment services and race/ethnicity: A national study of children and families involved with child welfare. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunger, A.C.; Chuang, E.; McBeath, B. Facilitating mental health service use for caregivers: Referral strategies among child welfare caseworkers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippelli, J.; Fallon, B.; Trocmé, N.; Fuller-Thomson, E.; Black, T. Infants and the decision to provide ongoing child welfare services. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2017, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell-Carrick, K. Child abuse and neglect. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development; Bremner, J.G., Wachs, T.D., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 819–845. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.R.; Appleyard, K. Infant pychological disorders. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development; Bremner, J.G., Wachs, T.D., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2014; Volume 1 and 2, pp. 934–961. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, S.; Kerns, S.E.U.; Trupin, E.W.; Conover, K.L.; Berliner, L. Child welfare caseworkers as service brokers for youth in foster care: Findings from Project Focus. Child Maltreat. 2012, 17, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, P.L.; Barth, R.P.; Hazen, A.L.; Landsverk, J.A. Child welfare as a gateway to domestic violence services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2005, 27, 1203–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.A.; Bunger, A.C.; Robertson, H.A.; Cao, Y.; West, K.Y. Child welfare caseworkers’ perspectives on the challenges of addressing mental health problems in early childhood. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, B.; Ma, J.; Allan, K.; Trocmé, N.; Jud, A. Opportunities for prevention and intervention with young children: Lessons from the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluke, J.D.; Chabot, M.; Fallon, B.; MacLaurin, B.; Blackstock, C. Placement decisions and disparities among aboriginal groups: An application of the decision making ecology through multi-level analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, T.; Trocmé, N.; Chabot, M.; Shlonsky, A.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Sinha, V. Placement of children in out-of-home care in Québec, Canada: When and for whom initial out-of-home placement is most likely to occur. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 2031–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, E.; Trocmé, N.; Fallon, B.; Ma, J. A troubled group? Adolescents in a Canadian child welfare sample. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 46, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrana, M. Pathways to Mental Health Services for Children and Youth in the Child Welfare System: A Focus on Social Workers’ Referral. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2010, 27, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, C.; Merritt, D.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.M.-S. Developmental Disabilities in Children Involved with Child Welfare: Correlates of Referrals for Service Provision. J. Public Child Welf. 2016, 10, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Motoyama, M. Development, CAPTA Part C referral and services among young children in the U.S. child welfare system. Child Maltreat. 2016, 21, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.D.; Hyde, J.; Leslie, L.K. “I Don’t Know What They Know”: Knowledge transfer in mandated referral from child welfare to early intervention. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, M.; Flynn, R.J.; Beaupré, J. Overview of out of home care in the USA and Canada. Psychosoc. Interv. 2013, 22, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, M.; Trocme, N. Children and Youth in Out-of-Home Care in Canada; McGill University, Centre for Research on Children and Families: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé, N.; Kyte, A.; Sinha, V.; Fallon, B. Urgent protection versus chronic need: Clarifying the dual mandate of child welfare services across Canada. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, K.; Baird, S.; Tarshis, S.; Black, T.; Fallon, B. Examining the response to different types of exposure to intimate partner violence. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resielience 2014, 2, 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, T. Beyond investigations: differential response in child protective services. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-94-007-7208-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn, F. Child Well-Being as Human Capital; Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tonmyr, L.; Williams, G.; Jack, S.M.; MacMillan, H.L. Infant placement in Canadian child maltreatment-related investigations. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palusci, V.J. Risk factors and services for child maltreatment among infants and young children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical issues in current practice. In Child Welfare: Connecting Research, Policy, and Practice; Kufeldt, K.; McKenzie, B. (Eds.) Wilfred Laurier University: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2011; pp. 553–568. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, B.; Van Wert, M.; Trocmé, N.; MacLaurin, B.; Sinha, V.; Lefebvre, R.; Allan, K.; Black, T. Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2013 (OIS-2013); Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.E. Reading and understanding multivariate statistics. In Reading and Understanding Multivariate Statistics; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-1-55798-273-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S. Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 458–482. [Google Scholar]

- Fallon, B.; Trocmé, N.; MacLaurin, B. Should child protection services respond differently to maltreatment, risk of maltreatment, and risk of harm? Child Abuse Negl. 2011, 35, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam-Hornstein, E.; Simon, J.; Eastman, A.; Magruder, J. Risk of re-reporting among infants who remain at home following alleged maltreatment. Child Maltreat. 2015, 20, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hélie, S.; Bouchard, C. Recurrent reporting of child maltreatment: State of knowledge and avenues for research. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, B.; Ma, J.; Black, T.; Wekerle, C. Characteristics of young parents investigated and opened for ongoing services in child welfare. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2011, 9, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, B.; Black, T.; Nikolova, K.; Tarshis, S.; Baird, S. Child welfare investigations involving exposure to intimate partner violence: Case and worker characteristics. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Resielience 2014, 2, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child & National Forum on Early Childhood Policy and Programs. Maternal Depression can Undermine the Development of Young Children; Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, A.F.; Landsverk, J.A.; Lau, A.S. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use among children in foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2003, 25, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hélie, S. A developmental approach to the risk of a first recurrence in child protective services. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, D.J.; Dalgleish, L.; Fluke, J.; Kern, H. The Decision-Making Ecology; American Human Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Freisthler, B. Need for and access to supportive services in the child welfare system. Geoj. Dordr. 2013, 78, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, B.; Trocmé, N. Factors associated with the decision to provide ongoing services: Are worker characteristics and organization geographic location important? In Child Welfare: Connecting Research, Policy, and Practice; Kufeldt, K., McKenzie, B., Eds.; Wilfred Laurier University: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2011; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton, J.; Kays-Burden, A.; Carter, C.; Bhasin, K.; Cairney, J.; Carrey, N.; Janus, M.; Kulkarni, C.; Williams, R. Supporting Ontario’s Youngest Minds: Investing in the Mental Health of Children under 6; Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).