Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Psychological Measures

3.2. Biomarker Data from Hair Samples

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Marx, C.E.; Pineles, S.L.; Locci, A.; Scioli-Salter, E.R.; Nillni, Y.I.; Liang, J.J.; Pinna, G. Neuroactive steroids and PTSD treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 649, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bellis, M.D.; Zisk, A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 23, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Alexander, N.; Stalder, T. An integrative model linking traumatization, cortisol dysregulation and posttraumatic stress disorder: Insight from recent hair cortisol findings. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 69, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.; Schindler, L.; Saar-Ashkenazy, R.; Bani Odeh, K.; Soreq, H.; Friedman, A.; Kirschbaum, C. Victims of war-Psychoendocrine evidence for the impact of traumatic stress on psychological well-being of adolescents growing up during the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Psychophysiology 2018, e13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudte, S.; Kolassa, I.-T.; Stalder, T.; Pfeiffer, A.; Kirschbaum, C.; Elbert, T. Increased cortisol concentrations in hair of severely traumatized Ugandan individuals with PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dajani, R.; Hadfield, K.; van Uum, S.; Greff, M.; Panter-Brick, C. Hair cortisol concentrations in war-affected adolescents: A prospective intervention trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 89, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewes, R.; Reich, H.; Skoluda, N.; Seele, F.; Nater, U.M. Elevated hair cortisol concentrations in recently fled asylum seekers in comparison to permanently settled immigrants and non-immigrants. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steudte, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Gao, W.; Alexander, N.; Schonfeld, S.; Hoyer, J.; Stalder, T. Hair cortisol as a biomarker of traumatization in healthy individuals and posttraumatic stress disorder patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, W.; Qiu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; et al. Hair cortisol level as a biomarker for altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in female adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maninger, N.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Reus, V.I.; Epel, E.S.; Mellon, S.H. Neurobiological and neuropsychiatric effects of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS). Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Zuiden, M.; Haverkort, S.Q.; Tan, Z.; Daams, J.; Lok, A.; Olff, M. DHEA and DHEA-S levels in posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analytic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 84, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hucklebridge, F.; Hussain, T.; Evans, P.; Clow, A. The diurnal patterns of the adrenal steroids cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in relation to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamin, H.S.; Kertes, D.A. Cortisol and DHEA in development and psychopathology. Horm. Behav. 2017, 89, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, F.R.; Pfingst, K.; Carnevali, L.; Sgoifo, A.; Nalivaiko, E. In the search for integrative biomarker of resilience to psychological stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Brand, S.R.; Golier, J.A.; Yang, R.-K. Clinical correlates of DHEA associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; Vythilingam, M.; Page, G.G. Low cortisol, high DHEA, and high levels of stimulated TNF-alpha, and IL-6 in women with PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 2008, 21, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, B.; Maayan, R.; Kotler, M.; Mester, R.; Gil-Ad, I.; Shtaif, B.; Weizman, A. Elevated circulatory level of GABA(A)—Antagonistic neurosteroids in patients with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. 2000, 30, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Vasek, J.; Lipschitz, D.S.; Vojvoda, D.; Mustone, M.E.; Shi, Q.; Gudmundsen, G.; Morgan, C.A.; Wolfe, J.; Charney, D.S. An increased capacity for adrenal DHEA release is associated with decreased avoidance and negative mood symptoms in women with PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oe, M.; Schnyder, U.; Schumacher, S.; Mueller-Pfeiffer, C.; Wilhelm, F.H.; Kalebasi, N.; Roos, D.; Hersberger, M.; Martin-Soelch, C. Lower plasma dehydroepiandrosterone concentration in the long term after severe accidental injury. Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, E.D.; Wilkinson, C.W.; Radant, A.D.; Petrie, E.C.; Dobie, D.J.; McFall, M.E.; Peskind, E.R.; Raskind, M.A. Glucocorticoid feedback sensitivity and adrenocortical responsiveness in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 50, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scioli-Salter, E.; Forman, D.E.; Otis, J.D.; Tun, C.; Allsup, K.; Marx, C.E.; Hauger, R.L.; Shipherd, J.C.; Higgins, D.; Tyzik, A.; et al. Potential neurobiological benefits of exercise in chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: Pilot study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2016, 53, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Ros, C.; Herbert, J.; Martinez, M. Different profiles of mental and physical health and stress hormone response in women victims of intimate partner violence. J. Acute Dis. 2014, 3, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Voorhees, E.E.; Dennis, M.F.; Calhoun, P.S.; Beckham, J.C. Association of DHEA, DHEAS, and cortisol with childhood trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 29, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Voorhees, E.E.; Dennis, M.F.; McClernon, F.J.; Calhoun, P.S.; Buse, N.A.; Beckham, J.C. The association of dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate with anxiety sensitivity and electronic diary negative affect among smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtz, C.; Godemann, K.; von Alm, C.; Wittekind, C.; Goemann, C.; Wiedemann, K.; Yassouridis, A.; Kellner, M. Effects of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder on metabolic risk, quality of life, and stress hormones in aging former refugee children. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011, 199, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radant, A.D.; Dobie, D.J.; Peskind, E.R.; Murburg, M.M.; Petrie, E.C.; Kanter, E.D.; Raskind, M.A.; Wilkinson, C.W. Adrenocortical responsiveness to infusions of physiological doses of ACTH is not altered in posttraumatic stress disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, D.; Vermetten, E.; Kelley, M.E. Cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone, and estradiol measured over 24 hours in women with childhood sexual abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olff, M.; Güzelcan, Y.; de Vries, G.-J.; Assies, J.; Gersons, B.P.R. HPA- and HPT-axis alterations in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmusson, A.M.; Pinna, G.; Paliwal, P.; Weisman, D.; Gottschalk, C.; Charney, D.; Krystal, J.; Guidotti, A. Decreased cerebrospinal fluid allopregnanolone levels in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, M.; Muhtz, C.; Peter, F.; Dunker, S.; Wiedemann, K.; Yassouridis, A. Increased DHEA and DHEA-S plasma levels in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and a history of childhood abuse. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 44, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olff, M.; de Vries, G.-J.; Guzelcan, Y.; Assies, J.; Gersons, B.P.R. Changes in cortisol and DHEA plasma levels after psychotherapy for PTSD. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007, 32, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D.; Rogosch, F.A. Personality, adrenal steroid hormones, and resilience in maltreated children: A multilevel perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kellner, M.; Muhtz, C.; Weinås, Å.; Ćurić, S.; Yassouridis, A.; Wiedemann, K. Impact of physical or sexual childhood abuse on plasma DHEA, DHEA-S and cortisol in a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test and on cardiovascular risk parameters in adult patients with major depression or anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R.; Pratchett, L.C.; Elmes, M.W.; Lehrner, A.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Koch, E.; Makotkine, I.; Flory, J.D.; Bierer, L.M. Glucocorticoid-related predictors and correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder treatment response in combat veterans. Interface Focus 2014, 4, 20140048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stalder, T.; Kirschbaum, C. Analysis of cortisol in hair—State of the art and future directions. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Stalder, T.; Foley, P.; Rauh, M.; Deng, H.; Kirschbaum, C. Quantitative analysis of steroid hormones in human hair using a column-switching LC-APCI-MS/MS assay. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 928, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennig, R. Potential problems with the interpretation of hair analysis results. Forensic Sci. Int. 2000, 107, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnar, M.; Quevedo, K. The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sagy, S.; Braun-Lewensohn, O. Adolescents under rocket fire: When are coping resources significant in reducing emotional distress? Glob. Health Promot. 2009, 16, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O.; Sagy, S. Community resilience and sense of coherence as protective factors in explaining stress reactions: Comparing cities and rural communities during missiles attacks. Community Ment. Health J. 2014, 50, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, G.; Fiore, F.; Castiglioni, M.; el Kawaja, H.; Said, M. Can Sense of Coherence Moderate Traumatic Reactions?: A Cross-Sectional Study of Palestinian Helpers Operating in War Contexts. Br. J. Soc. Work 2013, 43, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S.; Eshel, Y.; Zysberg, L.; Hantman, S.; Enosh, G. Sense of coherence and socio-demographic characteristics predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms and recovery in the aftermath of the Second Lebanon War. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, P.E.; Nelson, N.; Gustafsson, P.A. Diurnal cortisol levels, psychiatric symptoms and sense of coherence in abused adolescents. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2010, 64, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almedom, A.M.; Teclemichael, T.; Romero, L.M.; Alemu, Z. Postnatal salivary cortisol and sense of coherence (SOC) in Eritrean mothers. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2005, 17, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pynoos, R.; Rodrigues, N.; Steinberg, A.; Stuber, M.; Frederick, C. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (Child Version, Revision 1); UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Program: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, A.M.; Brymer, M.J.; Decker, K.B.; Pynoos, R.S. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2004, 6, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman, M.M.; Orvaschel, H.; Padian, N.M.S. Children’s Symptom and Social Functioning Self-Report Scales: Comparison of Mothers’ and Children’s Reports. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1980, 168, 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagy, S. Effects of Personal, Family, and Community Characteristics on Emotional Reactions in a Stress Situation. Youth Soc. 1998, 29, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomer, J.; Peder, R.; Rubin, A.H.; Lavie, P. Mini Sleep Questionnaire for screening large populations for EDS complaints. In Sleep ’84; Koella, W.P., Ruther, E., Schulz, H., Eds.; Gustav Fisher: Stuttgart, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pragst, F.; Balikova, M.A. State of the art in hair analysis for detection of drug and alcohol abuse. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 370, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 25.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Data Quality Assessment. Statistical Methods for Practitioners; Scholar’s Choice: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- van Voorhees, E.; Scarpa, A. The effects of child maltreatment on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2004, 5, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schury, K.; Koenig, A.M.; Isele, D.; Hulbert, A.L.; Krause, S.; Umlauft, M.; Kolassa, S.; Ziegenhain, U.; Karabatsiakis, A.; Reister, F.; et al. Alterations of hair cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone in mother-infant-dyads with maternal childhood maltreatment. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalder, T.; Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Alexander, N.; Klucken, T.; Vater, A.; Wichmann, S.; Kirschbaum, C.; Miller, R. Stress-related and basic determinants of hair cortisol in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 77, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, H.; Maeshima, H.; Kida, S.; Matsuzaka, H.; Shimano, T.; Nakano, Y.; Baba, H.; Suzuki, T.; Arai, H. Serum dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (S) levels in medicated patients with major depressive disorder compared with controls. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 146, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The HPA axis in major depression: Classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grass, J.; Miller, R.; Carlitz, E.H.D.; Patrovsky, F.; Gao, W.; Kirschbaum, C.; Stalder, T. In vitro influence of light radiation on hair steroid concentrations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 73, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wester, V.L.; van der Wulp, N.R.P.; Koper, J.W.; de Rijke, Y.B.; van Rossum, E.F.C. Hair cortisol and cortisone are decreased by natural sunlight. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 72, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Trauma Group (n = 36) | Trauma-Exposed Subgroup (n =17) | PTSD Subgroup (n = 39) | Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD) | 13.36 (1.29) | 13.41 (1.28) | 13.64 (1.33) | F2, 89 = 0.47 | 0.628 |

| Siblings (mean, SD) | 5.42 (2.17) | 4.18 (1.24) | 5.15 (1.76) | F2, 89 = 2.64 | 0.077 |

| Physical disease (%) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (5.1) | χ²2 = 1.83 | 0.401 |

| Medication (%) | 1 (4.3) a | 1 (7.7) b | 3 (13) c | χ²2 = 1.13 | 0.567 |

| Smoking (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Alcohol (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) d | 0 (0) | χ²2 = 4.74 | 0.094 |

| Drugs (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Physical development category | - | - | - | χ²8 = 4.16 | 0.842 |

| Academic level category | - | - | - | χ²8 = 5.04 | 0.753 |

| Family income category | - | - | - | χ²8 = 5.16 | 0.74 |

| Months of hair sample storage (mean, SD) | 25.54 (0.88) | 25.34 (0.79) | 25.56 (0.82) | F2, 89 = 0.46 | 0.634 |

| Non-Trauma Group (n = 36) | Trauma-Exposed Subgroup (n = 17) | PTSD Subgroup (n = 39) | Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA PTSD Reaction Index | |||||

| Number of potentially traumatic events (mean, SD) | 1.25 (1.4) | 4.35 (2.78) | 4.21 (2.52) | F2, 89 = 20.3 | < 0.001I |

| Time since the worst event | - | - | - | χ²12 = 5.23 | 0.95 |

| Dissociation during the event (%) | 4 (11.1) | 7 (41.2) | 22 (56.4) | χ²2 = 16.96 | < 0.001 |

| Intrusion Severity (mean, SD) | 5.81 (5.08) | 4.88 (4.23) | 7.67 (4.07) | F2, 89 = 2.8 | 0.066 |

| Avoidance Severity (mean, SD) | 6.97 (7.44) | 2.82 (2.67) | 8.92 (3.65) | F2, 89 = 7.67 | 0.001 II |

| Arousal Severity (mean, SD) | 7.03 (5.94) | 6.12 (4.69) | 10.59 (3.47) | F2, 89 = 7.47 | 0.001 III |

| PTSD Severity (mean, SD) | 18.08 (16.85) | 12.94 (6.96) | 24.44 (8.37) | F2, 89 = 5.8 | 0.004 IV |

| STAI-Y-Trait (mean, SD) | 45.19 (6.57) | 41.47 (6.71) | 44.52 (7.21) a | F2, 89 = 1.76 | 0.178 |

| CES-DC | |||||

| Depression Severity (mean, SD) | 18.69 (11.02) | 16.24 (8.3) | 22.64 (6.62) | F2, 89 = 3.64 | 0.03 V |

| Depression Diagnosis (%) | 18 (50) | 6 (35.3) | 34 (87.2) | χ²2 = 17.99 | < 0.001 |

| MSQ (mean, SD) | 24.36 (13.68) | 27.59 (12.7) | 32.74 (11.97) | F2, 89 = 4.07 | 0.02 VI |

| SoC | |||||

| SOC-13 (mean, SD) | 55.56 (10.17) | 58.53 (11.77) | 54.77 (8.47) | F2, 89 = 0.88 | 0.417 |

| SOFC (mean, SD) | 52.66 (6.86) | 53.65 (9.13) | 50.69 (6.95) | F2, 89 = 1.19 | 0.31 |

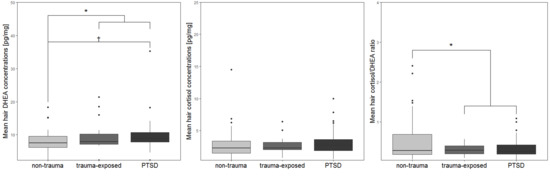

| Biomarker | |||||

| Hair DHEA (mean, SD) | 7.77 (3.73) | 9.74 (4.77) | 9.89 (5.17) a | F2, 88 = 3.2 | 0.046 c,VII |

| Hair cortisol (mean, SD) | 2.92 (2.56) b | 2.71 (1.39) | 3.24 (2.02) | F2, 88 = 0.74 | 0.48 c |

| Hair cortisol/DHEA ratio (mean, SD) | 0.55 (0.59) | 0.31 (0.13) | 0.36 (0.25) | F2, 89 = 2.35 | 0.101 c |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schindler, L.; Shaheen, M.; Saar-Ashkenazy, R.; Bani Odeh, K.; Sass, S.-H.; Friedman, A.; Kirschbaum, C. Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020

Schindler L, Shaheen M, Saar-Ashkenazy R, Bani Odeh K, Sass S-H, Friedman A, Kirschbaum C. Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank. Brain Sciences. 2019; 9(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchindler, Lena, Mohammed Shaheen, Rotem Saar-Ashkenazy, Kifah Bani Odeh, Sophia-Helen Sass, Alon Friedman, and Clemens Kirschbaum. 2019. "Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank" Brain Sciences 9, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020

APA StyleSchindler, L., Shaheen, M., Saar-Ashkenazy, R., Bani Odeh, K., Sass, S.-H., Friedman, A., & Kirschbaum, C. (2019). Victims of War: Dehydroepiandrosterone Concentrations in Hair and Their Associations with Trauma Sequelae in Palestinian Adolescents Living in the West Bank. Brain Sciences, 9(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9020020