Green Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Biomass and Their Application in Meat as Natural Antioxidant

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Plant Extracts as Natural Antioxidants

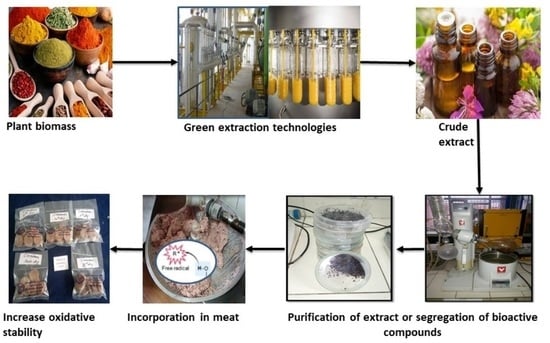

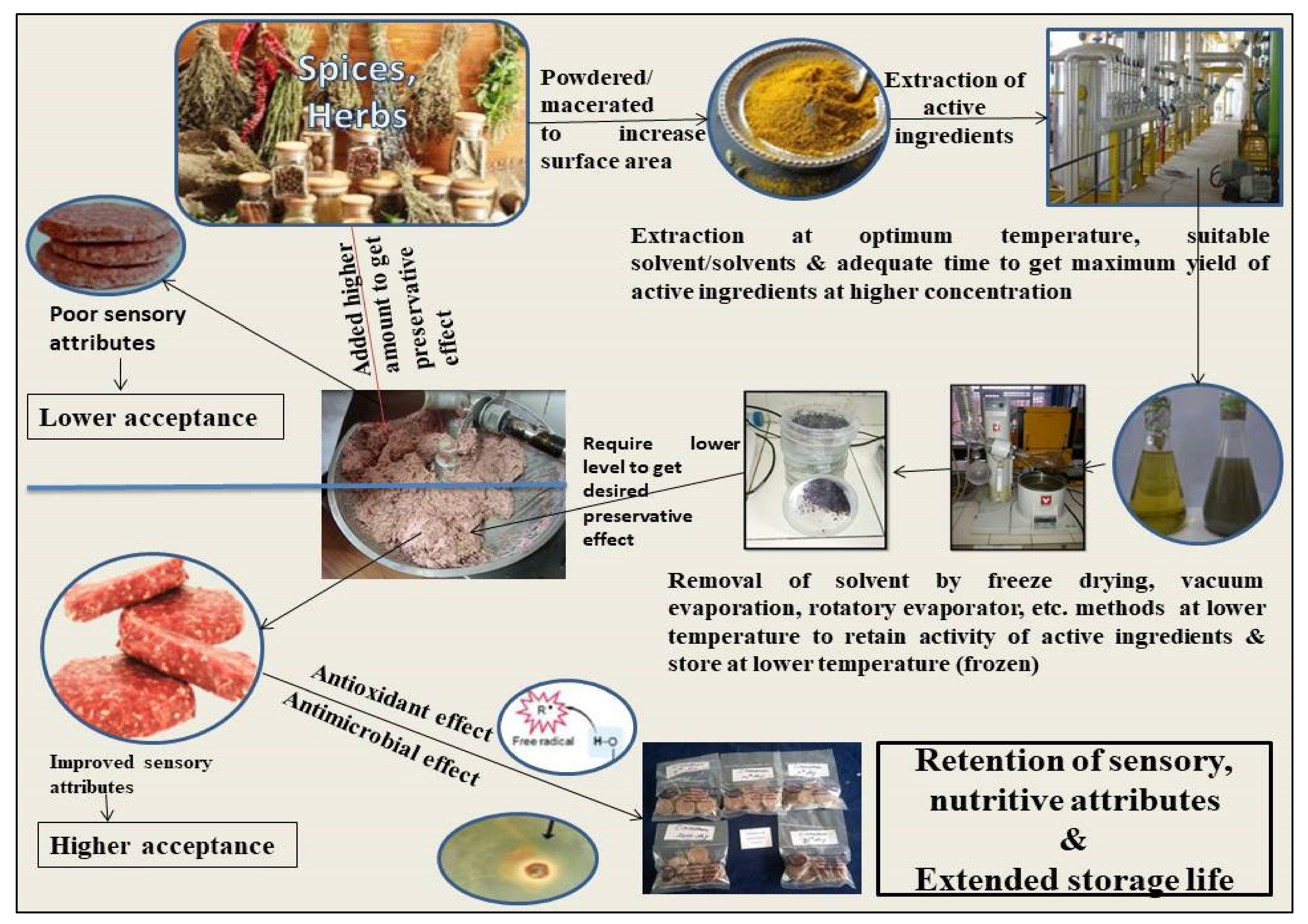

3. Extraction Protocols

Green Solvents for Extraction

4. Extraction Methodology

4.1. Traditional Extraction Methods

4.2. Greener/Advanced Extraction Methods

5. Supercritical Fluid Extraction

5.1. Selection of SCF

5.1.1. Carbon Dioxide as a Supercritical Fluid (SC CO2)

- (a)

- (b)

- Low critical temperature, suitable for the extraction of heat-labile compounds;

- (c)

- © High density (467.6 kg/m3), at a critical point, leading to higher dissolving power;

- (d)

- Easily adjustable/tunable density, such as, at 42 °C, 766.5 kg/m3 density at 150 bar, 950 kg/m3 at 400 bar and 1075 kg/m3 (near to liquid CO2 i.e., 1256.7 kg/m3) at 750 bar. It allows the collecting of every compound present in the plant biomass by suitable processing conditions, such as [33]:

- (e)

- Readily available in the environment and economy;

- (f)

- Non-toxic, colorless, odorless, and non-inflammable gas;

- (g)

- Purity and recyclability;

- (h)

- Wide versatility during fractionalization and extraction.

5.1.2. Propane as a Supercritical Fluid

5.2. SCF Extraction Process

- (a)

- Penetration of the matrix;

- (b)

- Supercritical solvent solubilizes the solutes/plant compounds inside the pores;

- (c)

- Internal diffusion of the solute until it has reached the external surface;

- (d)

- External diffusion of solutes from the solid–fluid interface of the supercritical fluid;

- (e)

5.3. Other Extraction Methods as SFE-Adjunct

5.3.1. Enzyme-Assisted SFE

5.3.2. Ultrasound-Assisted SFE

5.4. SFE of Bioactive Compounds

6. Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE)

7. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

8. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE)

9. Pulsed Electric Field Assisted Extraction

10. Miscellaneous

11. Plant Extracts as Natural Antioxidants in Meat

12. Current Scenario

13. Prospects and Challenges

14. Conclusions

Authors Contribution

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Mehta, N.; Malav, O.P.; Verma, A.K.; Kumar, D.; Rathour, M. Antioxidant and antimicrobial efficacy of sapota powder in pork patties stored under different packaging conditions. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2018, 38, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Xiong, Y.L. Natural antioxidants as food and feed additives to promote health benefits and quality of meat products: A review. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, S.-C.; Chen, C. Effects of origins and fermentation time on the antioxidant activities of kombucha. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Verma, A.K.; Umaraw, P.; Mehta, N.; Rajeev, R. Natural extracts are very promising: They are a novel green alternative to synthetic preservatives for the meat industry. Fleischwirtsch. Int. J. Meat Prod. Meat Process. 2020, 3, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Efenberger-Szmechtyk, M.; Nowak, A.; Czyzowska, A. Plant extracts rich in polyphenols: Antibacterial agents and natural preservatives for meat and meat products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Chen, W.-F.; Zhou, B. Antioxidant synergism of green tea polyphenols with alpha-tocopherol and L-ascorbic acid in SDS micelles. Biochimie 2008, 90, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-K.; Shibamoto, T. Antioxidant assays for plant and food components. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1655–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Verma, A.K.; Umaraw, P.; Mehta, N.; Malav, O.P. Plant phenolics as natural preservatives in food system. In Plant Phenolics in Sustainable Agriculture; Lone, R., Shuab, R., Kamili, A.N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 367–406. ISBN 978-981-15-4890-1. [Google Scholar]

- Vuong, Q.V.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Nguyen, M.H.; Golding, J.B.; Roach, P.D. Isolation of green tea catechins and their utilization in the food industry. Food Rev. Int. 2011, 27, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrava, D.G.; Moldovan, C.; Raba, D.-N.; Popa, M.-V. Vitamin C, chlorophylls, carotenoids and xanthophylls content in some basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) leaves extracts. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2012, 18, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Negi, P.S. Plant extracts for the control of bacterial growth: Efficacy, stability and safety issues for food application. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 156, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, L.; Chograni, H.; Elferchichi, M.; Zaouali, Y.; Zoghlami, N.; Mliki, A. Variations in Tunisian wormwood essential oil profiles and phenolic contents between leaves and flowers and their effects on antioxidant activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 46, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathour, M.; Malav, O.P.; Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Mehta, N. Storage stability of chevon rolls incorporated with ethanolic extracts of aloe vera and cinnamon bark at refrigeration temperature (4 ± 1 °C). J. Anim. Res. 2017, 7, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathour, M.; Malav, O.P.; Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Mehta, N. Standardization of protocols for extraction of aloe vera and cinnamon bark extracts. J. Anim. Res. 2017, 7, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casazza, A.A.; Aliakbarian, B.; Perego, P. Recovery of phenolic compounds from grape seeds: Effect of extraction time and solid–liquid ratio. Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 25, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.-y.; Chuang, C.-h.; Chen, H.-c.; Wan, C.-j.; Chen, T.-l.; Lin, L. Bioactive components analysis of two various gingers (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and antioxidant effect of ginger extracts. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Datta, N.; Singanusong, R.; Liu, X.; Duan, J.; Raymont, K.; Lisle, A.; Xu, Y. HPLC analyses of flavanols and phenolic acids in the fresh young shoots of tea (Camellia sinensis) grown in Australia. Food Chem. 2004, 84, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokhar, S.; Magnusdottir, S.G.M. Total phenol, catechin, and caffeine contents of teas commonly consumed in the United Kingdom. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.D.; Angkawijaya, A.E.; Tran-Nguyen, P.L.; Huynh, L.H.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Ismadji, S.; Ju, Y.H. Effect of extraction solvent on total phenol content, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant activity of Limnophila aromatica. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, M.A.; Bosco, S.J.D.; Mir, S.A. Plant extracts as natural antioxidants in meat and meat products. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmen, N.; Sari, F.; Velioglu, Y.S. Effects of extraction solvents on concentration and antioxidant activity of black and black mate tea polyphenols determined by ferrous tartrate and Folin-Ciocalteu methods. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Gómez-Salazar, J.A.; Jaime-Patlán, M.; Sosa-Morales, M.E.; Lorenzo, J.M. Plant extracts obtained with green solvents as natural antioxidants in fresh meat products. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Abert Vian, M.; Ravi, H.K.; Khadhraoui, B.; Hilali, S.; Perino, S.; Fabiano Tixier, A.-S. Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of food and natural products: Panorama, principles, applications and prospects. Molecules 2019, 24, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.H.; Verpoorte, R. Green solvents for the extraction of bioactive compounds from natural products using ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 26, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekariya, R.L. A review of ionic liquids: Applications towards catalytic organic transformations. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 227, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.P.F.F.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; Duarte, A.C. Supercritical fluid extraction of bioactive compounds. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 76, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harbourne, N.; Marete, E.; Jacquier, J.; O’Riordan, D. Conventional extraction techniques for phytochemicals. In Handbook of Plant Food Phytochemicals; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Heleno, S.A.; Diz, P.; Prieto, M.A.; Barros, L.; Rodrigues, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction to obtain mycosterols from Agaricus bisporus L. by response surface methodology and comparison with conventional Soxhlet extraction. Food Chem. 2016, 197 Pt B, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Zou, Y.; Chen, X. A comparison of volatile fractions obtained from Lonicera macranthoides via different extraction processes: Ultrasound, microwave, Soxhlet extraction, hydrodistillation, and cold maceration. Integr. Med. Res. 2015, 4, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aminzare, M.; Hashemi, M.; Ansarian, E.; Bimkar, M.; Azar, H.H.; Mehrasbi, M.R.; Daneshamooz, S.; Raeisi, M.; Jannat, B.; Afshari, A. Using natural antioxidants in meat and meat products as preservatives: A review. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2019, 7, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rombaut, N.; Tixier, A.-S.; Bily, A.; Chemat, F. Green extraction processes of natural products as tools for biorefinery. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2014, 8, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, K.Y.; Parat, M.O.; Shaw, P.N.; Falconer, J.R. Solvent supercritical fluid technologies to extract bioactive compounds from natural sources: A review. Molecules 2017, 22, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capuzzo, A.; Maffei, M.E.; Occhipinti, A. Supercritical fluid extraction of plant flavors and fragrances. Molecules 2013, 18, 7194–7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pourmortazavi, S.M.; Hajimirsadeghi, S.S. Supercritical fluid extraction in plant essential and volatile oil analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1163, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, M.; Baumann, D.; Adler, S. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of selected medicinal plants-effects of high pressure and added ethanol on yield of extracted substances. Phytochem. Anal. 2004, 15, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, S.; Daood, H.G.; Toth-Markus, M.; Illés, V. Extraction of cardamom oil by supercritical carbon dioxide and sub-critical propane. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2008, 44, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Castro-Puyana, M.; Mendiola, J.; Ibáñez, E. Compressed fluids for the extraction of bioactive compounds. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 43, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibañez, E. Sub- and supercritical fluid extraction of functional ingredients from different natural sources: Plants, food-by-products, algae and microalgae: A review. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, C.G.; Meireles, M.A.A. Supercritical fluid extraction of bioactive compounds: Fundamentals, applications and economic perspectives. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010, 3, 340–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, E.S.; Cheong, J.S.H.; Goh, D. Pressurized hot water extraction of bioactive or marker compounds in botanicals and medicinal plant materials. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1112, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, P.F.; Maia, N.B.; Carmello, Q.A.C.; Catharino, R.R.; Eberlin, M.N.; Meireles, M.A.A. Sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) extracts obtained by supercritical fluid extraction (SFE): Global yields, chemical composition, antioxidant activity, and estimation of the cost of manufacturing. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2008, 1, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámiz-Gracia, L.; Luque de Castro, M.D. Continuous subcritical water extraction of medicinal plant essential oil: Comparison with conventional techniques. Talanta 2000, 51, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchpole, O.J.; Grey, J.B.; Perry, N.B.; Burgess, E.J.; Redmond, W.A.; Porter, N.G. Extraction of chili, black pepper, and ginger with near-critical CO2, propane, and dimethyl ether: Analysis of the extracts by quantitative nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 4853–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.; Mesomo, M.C.; Pianoski, K.E.; Torres, Y.R.; Corazza, M.L. Extraction of inflorescences of Musa paradisiaca L. using supercritical CO2 and compressed propane. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 113, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.R.F.; Cantelli, K.C.; Soares, M.B.A.; Tres, M.V.; Oliveira, D.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Oliveira, J.V.; Treichel, H.; Mazutti, M.A. Enzymatic hydrolysis of non-treated sugarcane bagasse using pressurized liquefied petroleum gas with and without ultrasound assistance. Renew. Energy 2015, 83, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanqui, A.B.; De Morais, D.R.; Da Silva, C.M.; Santos, J.M.; Gomes, S.T.M.; Visentainer, J.V.; Eberlin, M.N.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Matsushita, M. Subcritical extraction of flaxseed oil with n-propane: Composition and purity. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Da Silva, C.M.; Zanqui, A.B.; Gohara, A.K.; De Souza, A.H.P.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Visentainer, J.V.; Rovigatti Chiavelli, L.U.; Bittencourt, P.R.S.; Da Silva, E.A.; Matsushita, M. Compressed n-propane extraction of lipids and bioactive compounds from Perilla (Perilla frutescens). J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 102, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.A.; Bariccatti, R.A.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Schneider, R.; Palú, F.; Da Silva, C.; Da Silva, E.A. Extraction of crambe seed oil using subcritical propane: Kinetics, characterization and modeling. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 104, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, A.S.; Podestá, R.; Block, J.M.; Franceschi, E.; Dariva, C.; Lanza, M. Extraction of pequi (Caryocar coriaceum) pulp oil using subcritical propane: Determination of process yield and fatty acid profile. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 101, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederssetti, M.M.; Palú, F.; Da Silva, E.A.; Rohling, J.H.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Dariva, C. Extraction of canola seed (Brassica napus) oil using compressed propane and supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Food Eng. 2011, 102, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.P.; Fagundes-Klen, M.R.; Silva, E.A.; Cardozo Filho, L.; Santos, J.N.; Freitas, L.S.; Dariva, C. Extraction of sesame seed (Sesamun indicum L.) oil using compressed propane and supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2010, 52, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimet, G.; da Silva, E.A.; Palú, F.; Dariva, C.; dos Santos Freitas, L.; Neto, A.M.; Filho, L.C. Extraction of sunflower (Heliantus annuus L.) oil with supercritical CO2 and subcritical propane: Experimental and modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 168, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.F.; Dal Prá, V.; de Souza, M.; Lunelli, F.C.; Abaide, E.; da Silva, J.R.F.; Kuhn, R.C.; Martinez, J.; Mazutti, M.A. Extraction of rice bran oil using supercritical CO2 and compressed liquefied petroleum gas. J. Food Eng. 2016, 170, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dal Prá, V.; Soares, J.F.; Monego, D.L.; Vendruscolo, R.G.; Freire, D.M.G.; Alexandri, M.; Koutinas, A.; Wagner, R.; Mazutti, M.A.; Da Rosa, M.B. Extraction of bioactive compounds from palm (Elaeis guineensis) pressed fiber using different compressed fluids. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 112, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, E.; De Marco, I. Supercritical fluid extraction and fractionation of natural matter. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2006, 38, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duba, K.S.; Fiori, L. Supercritical CO2 extraction of grape seed oil: Effect of process parameters on the extraction kinetics. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 98, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Dhyani, P.; Bhatt, I.D.; Rawal, R.S.; Pande, V. Optimization extraction conditions for improving phenolic content and antioxidant activity in Berberis asiatica fruits using response surface methodology (RSM). Food Chem. 2016, 207, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bimakr, M.; Rahman, R.A.; Ganjloo, A.; Taip, F.S.; Salleh, L.M.; Sarker, M.Z.I. Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of bioactive flavonoid compounds from spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) leaves by using response surface methodology. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad-Sadeghi, M.; Taji, S.; Goodarznia, I. Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of essential oil from Dracocephalum kotschyi Boiss: An endangered medicinal plant in Iran. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1422, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, B.; Simándi, B. Effects of particle size distribution, moisture content, and initial oil content on the supercritical fluid extraction of paprika. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2008, 46, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crampon, C.; Mouahid, A.; Toudji, S.A.A.; Leṕine, O.; Badens, E. Influence of pretreatment on supercritical CO2 extraction from Nannochloropsis oculata. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 79, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovic, J.; Ristic, M.; Skala, D. Supercritical CO2 extraction of Helichrysum italicum: Influence of CO2 density and moisture content of plant material. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2011, 57, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, C.; Decorti, D.; Natolino, A. Microwave pretreatment of Moringa oleifera seed: Effect on oil obtained by pilot-scale supercritical carbon dioxide extraction and Soxhlet apparatus. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 107, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Bhattacharjee, P. Enzyme-assisted supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of black pepper oleoresin for enhanced yield of piperine-rich extract. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2015, 120, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Sultana, B.; Anwar, F.; Adnan, A.; SSH, R. Enzyme-assisted supercritical fluid extraction of phenolic antioxidants from pomegranate peel. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 104, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Sultana, B.; Akram, S.; Anwar, F.; Adnan, A.; Rizvi, S.S.H. Enzyme-assisted supercritical fluid extraction: An alternative and green technology for non-extractable polyphenols. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 3645–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenucci, M.S.; De Caroli, M.; Marrese, P.P.; Iurlaro, A.; Rescio, L.; Böhm, V.; Dalessandro, G.; Piro, G. Enzyme-aided extraction of lycopene from high-pigment tomato cultivars by supercritical carbon dioxide. Food Chem. 2015, 170, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Porto, C.; Natolino, A.; Decorti, D. Effect of ultrasound pre-treatment of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed on supercritical CO2 extraction of oil. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1748–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Said, P.P.; Arya, O.P.; Pradhan, R.C.; Singh, R.S.; Rai, B.N. Separation of oleoresin from ginger rhizome powder using green processing technologies. J. Food Process Eng. 2015, 38, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, S.; Kentish, S.E.; Mawson, R.; Ashokkumar, M. Ultrasonic enhancement of the supercritical extraction from ginger. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2006, 13, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.-C.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Y.-C. Extraction of α-humulene-enriched oil from clove using ultrasound-assisted supercritical carbon dioxide extraction and studies of its fictitious solubility. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H.; Mishima, K.; Sharmin, T.; Ito, S.; Kawakami, R.; Kato, T.; Misumi, M.; Suetsugu, T.; Orii, H.; Kawano, H.; et al. Ultrasonically enhanced extraction of luteolin and apigenin from the leaves of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. using liquid carbon dioxide and ethanol. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 29, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.L.B.; Arroio Sergio, C.S.; Santos, P.; Barbero, G.F.; Rezende, C.A.; Martínez, J. Effect of ultrasound on the supercritical CO2 extraction of bioactive compounds from dedo de moça pepper (Capsicum baccatum L. var. pendulum). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 31, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.; Aguiar, A.C.; Barbero, G.F.; Rezende, C.A.; Martínez, J. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of capsaicinoids from malagueta pepper (Capsicum frutescens L.) assisted by ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 22, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.-C.; Yang, Y.-C. Kinetic studies for ultrasound-assisted supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of triterpenic acids from healthy tea ingredient Hedyotis diffusa and Hedyotis corymbosa. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 142, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, E.; Golás, Y.; Blanco, A.; Gallego, J.A.; Blasco, M.; Mulet, A. Mass transfer enhancement in supercritical fluids extraction by means of power ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2004, 11, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaman, F.S.; Moraes, L.A.B.; West, C.; Ferreira, N.J.; Oliveira, A.L. Supercritical fluid extracts from the Brazilian cherry (Eugenia uniflora L.): Relationship between the extracted compounds and the characteristic flavour intensity of the fruit. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotra, P.; Singh, S.K.; Nagpal, K. Supercritical fluid technology: A promising approach in pharmaceutical research. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2013, 18, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Reinoso, B.; Moure, A.; Domínguez, H.; Parajó, J.C. Supercritical CO2 extraction and purification of compounds with antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2441–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guelph, L.; Davidson, V.J.; Kakuda, Y. Analysis of volatile flavor components in roasted peanuts using supercritical fluid extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. food Chem. 1996, 44, 2694–2699. [Google Scholar]

- Banchero, M.; Pellegrino, G.; Manna, L. Supercritical fluid extraction as a potential mitigation strategy for the reduction of acrylamide level in coffee. J. Food Eng. 2013, 115, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikes, D.L.; Scott, B.; Gorzovalitis, N.A. Quantitation of volatile oils in ground cumin by supercritical fluid extraction and gas chromatography with flame ionization detection. J. AOAC Int. 2001, 84, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Braga, M.E.M.; Meireles, M.A.A. Accelerated solvent extraction and fractioned extraction to obtain the curcuma longa volatile oil and oleoresin. J. Food Process Eng. 2007, 30, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazazi, H.; Rezaei, K.; Ghotb-Sharif, S.J.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Yamini, Y. Analytical, nutritional and clinical methods. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumoro, A.; Singh, H. Extraction of Sarawak black pepper essential oil using supercritical carbon dioxide. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2010, 35, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, F.A.; das Cardoso, M.G.; Guimarães, L.G.L.; Queiroz, F.; Barbosa, L.C.A.; Morais, A.R.; Nelson, D.L.; Andrade, M.A.; Zacaroni, L.M.; Pimentel, S.M.N.P. Extracts from the leaves of Piper piscatorum (Trel. Yunc.) obtained by supercritical extraction of with CO2, employing ethanol and methanol as co-solvents. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Mishra, V.; Imison, B.; Palmer, M.; Fairclough, R. Use of adsorbent and supercritical carbon dioxide to concentrate flavor compounds from orange oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Opstaele, F.; Goiris, K.; De Rouck, G.; Aerts, G.; De Cooman, L. Production of novel varietal hop aromas by supercritical fluid extraction of hop pellets. Part 1: Preparation of single variety total hop essential oils and polar hop essences. Cerevisia 2013, 37, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.M.A.; Oliveira, E.L.G.; Freire, C.S.R.; Couto, R.M.; Simões, P.C.; Neto, C.P.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Silva, C.M. Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Eucalyptus globulus Bark—A Promising Approach for Triterpenoid Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 7648–7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Chang, L.; Zhao, X.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis on compounds in volatile oils extracted from yuan zhi (Radix polygalae) and shi chang pu (Acorus tatarinowii) by supercritical CO2. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2012, 32, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opstaele, F.; Goiris, K.; De Rouck, G.; Aerts, G.; Cooman, L. Production of novel varietal hop aromas by supercritical fluid extraction of hop pellets—Part 2: Preparation of single variety floral, citrus, and spicy hop oil essences by density programmed supercritical fluid extraction. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 71, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Ma, X.; Qiu, B.-H.; Chen, J.; Bian, L.; Pan, L. Parameters optimization of supercritical fluid-CO2 extracts of Frankincense using response surface methodology and its pharmacodynamics effects. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, J.; Olivares, M.; Alzaga, M.; Etxebarria, N. Optimisation and characterisation of marihuana extracts obtained by supercritical fluid extraction and focused ultrasound extraction and retention time locking GC-MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, M.K.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, Y.-S. Effect of supercritical carbon dioxide decaffeination on volatile components of green teas. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, S497–S502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, E.M.B.D.; Martínez, J.; Chiavone-Filho, O.; Rosa, P.T.V.; Domingos, T.; Meireles, M.A.A. Extraction of volatile oil from Croton zehntneri Pax et Hoff with pressurized CO2: Solubility, composition and kinetics. J. Food Eng. 2005, 69, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouki, H.; Piras, A.; Marongiu, B.; Rosa, A.; Dessì, M.A. Extraction and separation of volatile and fixed oils from berries of Laurus nobilis L. by Supercritical CO2. Molecules 2008, 13, 1702–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Almeida, P.; Mezzomo, N.; Ferreira, S. Extraction of Mentha spicata L. volatile compounds: Evaluation of process parameters and extract composition. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, K.; Goodarznia, I. Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of essential oil from spearmint (Mentha spicata L.) leaves by using Taguchi methodology. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 67, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ahmady, S.H.; Ashour, M.L.; Wink, M. Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of the essential oils of Psidium guajava fruits and leaves. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2013, 25, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, P.F.; Chaves, F.C.M.; Ming, L.I.N.C.; Petenate, A.J.; Meireles, M.A.A. Global yields, chemical compositions and antioxidant activities of clove basil (Ocimum gratissimum L.) extracts obtained by supercritical fluid extraction. J. Food Process Eng. 2006, 29, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, B.P.; Gouveia, L.; Matos, P.G.S.; Cristino, A.F.; Palavra, A.F.; Mendes, R.L. Supercritical extraction of lycopene from tomato industrial wastes with ethane. Molecules 2012, 17, 8397–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigano, J.; Coutinho, J.P.; Souza, D.N.; Baroni, N.A.F.; Godoy, H.T.; Macedo, J.A.; Martinez, J. Exploring the selectivity of supercritical CO2 to obtain nonpolar fractions of passion fruit bagasse extracts. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 110, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimakr, M.; Rahman, R.A.; Taip, F.S.; Adzahan, N.M.; Sarker, M.Z.I.; Ganjloo, A. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of seed oil from winter melon (Benincasa hispida) and its antioxidant activity and fatty acid composition. Molecules 2013, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladić, K.; Jarni, K.; Barbir, T.; Vidović, S.; Vladić, J.; Bilić, M.; Jokić, S. Supercritical CO2 extraction of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 76, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, P.T.W.; de Carvalho, P.P.; Rocha, T.B.; Pessoa, F.L.P.; Azevedo, D.A.; Mendes, M.F. Evaluation of the composition of Carica papaya L. seed oil extracted with supercritical CO2. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 11, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Belayneh, H.D.; Wehling, R.; Cahoon, E.; Ciftci, N.O. Extraction of omega-3-rich oil from Camelina sativa seed using supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 104, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygoda, K.; Wejnerowska, G. Extraction of tocopherol-enriched oils from Quinoa seeds by supercritical fluid extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 63, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Guo, H.; Zhang, A.; Wang, Y. Application of response surface methodology to optimise supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of volatile compounds from Crocus sativus. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmus, T.T.; Kopf, S.F.M.; Paula, J.T.; Aguiar, A.C.; Duarte, G.H.B.; Eberlin, M.N.; Cabral, F.A. Ethanolic and hydroalcoholic extracts of pitanga leaves (Eugenia uniflora L.) and their fractionation by supercritical technology. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 36, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, D. A parametric study of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of oil from Moringa oleifera seeds using a response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 113, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttarattanamongkol, K.; Siebenhandl-Ehn, S.; Schreiner, M.; Petrasch, A. Pilot-scale supercritical carbon dioxide extraction, physico-chemical properties and profile characterization of Moringa oleifera seed oil in comparison with conventional extraction methods. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 58, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Srivastav, P.; Mishra, H.N. Optimization of process variables for supercritical fluid extraction of ergothioneine and polyphenols from Pleurotus ostreatus and correlation to free-radical scavenging activity. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, B.A.; Hamerski, F.; Clausen, M.P.; Errico, M.; de Paula Scheer, A.; Corazza, M.L. Compressed fluids extraction methods, yields, antioxidant activities, total phenolics and flavonoids content for Brazilian Mantiqueira hops. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2021, 170, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Raofie, F. Micronization of vincristine extracted from Catharanthus roseus by expansion of supercritical fluid solution. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 146, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Carmona, L.; Ortiz-Moreno, A.; Ceballos-Reyes, G.; Mendiola, J.A.; Ibáñez, E. Valorization of cacao pod husk through supercritical fluid extraction of phenolic compounds. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 131, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, P.N.; Fetzer, D.L.; do Amaral, W.; de Andrade, E.F.; Corazza, M.L.; Masson, M.L. Antioxidant activity and fatty acid profile of yacon leaves extracts obtained by supercritical CO2 + ethanol solvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 146, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczykolan, A.; Pietrzak, W.; Rój, E.; Nowak, R. Effects of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction (SC-CO2) on the content of tiliroside in the extracts from Tilia L. flowers. Open Chem. 2019, 17, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, J.C.W.; Dicko, C.; Kini, F.B.; Bonzi-Coulibaly, Y.L.; Dey, E.S. Enhanced extraction of flavonoids from Odontonema strictum leaves with antioxidant activity using supercritical carbon dioxide fluid combined with ethanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 131, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokić, S.; Molnar, M.; Jakovljević, M.; Aladić, K.; Jerković, I. Optimization of supercritical CO2 extraction of Salvia officinalis L. leaves targeted on Oxygenated monoterpenes, α-humulene, viridiflorol and manool. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 133, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.N.; Ribeiro, A.S.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Vedoy, D.; Alves, P.B. Extraction from leaves of Piper klotzschianum using supercritical carbon dioxide and co-solvents. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 147, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Lima, M.; Kestekoglou, I.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Supercritical fluid extraction of carotenoids from vegetable waste matrices. Molecules 2019, 24, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Andrade Lima, M.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Chatzifragkou, A. Optimisation and modelling of supercritical CO2 extraction process of carotenoids from carrot peels. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 133, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Hernández, L.A.; Espinosa-Victoria, J.R.; Trejo, A.; Guerrero-Beltrán, J. CO2-supercritical extraction, hydrodistillation and steam distillation of essential oil of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis). J. Food Eng. 2017, 200, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, P.C.; Santos, K.A.; Palú, F.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; da Silva, C.; da Silva, E.A. Evaluation of the effects of temperature and pressure on the extraction of eugenol from clove (Syzygium aromaticum) leaves using supercritical CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 143, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyeneche, R.; Fanovich, A.; Rodriguez Rodrigues, C.; Nicolao, M.C.; Di Scala, K. Supercritical CO2 extraction of bioactive compounds from radish leaves: Yield, antioxidant capacity and cytotoxicity. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 135, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia-Mendoza, M.P.; Paula, J.T.; Paviani, L.C.; Cabral, F.A.; Martinez-Correa, H.A. Extracts from mango peel by-product obtained by supercritical CO2 and pressurized solvent processes. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.T.; Veggi, P.C.; Meireles, M.A.A. Optimization and economic evaluation of pressurized liquid extraction of phenolic compounds from jabuticaba skins. J. Food Eng. 2012, 108, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machado, A.P.D.F.; Pasquel-Reátegui, J.L.; Barbero, G.F.; Martínez, J. Pressurized liquid extraction of bioactive compounds from blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L.) residues: A comparison with conventional methods. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cai, F.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G. Optimisation of pressurised water extraction of polysaccharides from blackcurrant and its antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, T.; Bajerová, P.; Kremr, D.; Eisner, A.; Ventura, K. Central composite design of pressurised hot water extraction process for extracting capsaicinoids from chili peppers. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 40, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoddami, A.; Wilkes, M.A.; Roberts, T.H. Techniques for Analysis of Plant Phenolic Compounds. Molecules 2013, 18, 2328–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajha, H.N.; Boussetta, N.; Louka, N.; Maroun, R.G.; Vorobiev, E. Effect of alternative physical pretreatments (pulsed electric field, high voltage electrical discharges and ultrasound) on the dead-end ultrafiltration of vine-shoot extracts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 146, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kek, S.P.; Chin, N.L.; Yusof, Y.A. Direct and indirect power ultrasound assisted pre-osmotic treatments in convective drying of guava slices. Food Bioprod. Process. 2013, 91, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.K.; Li, M.F.; Sun, R.C. Identifying the impact of ultrasound-assisted extraction on polysaccharides and natural antioxidants from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, G.L.; Dimitrov, K.; Vauchel, P.; Nikov, I. Kinetics of ultrasound assisted extraction of anthocyanins from Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry) wastes. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2014, 92, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, V.; Ilanhtiraiyan, S.; Ilayaraja, K.; Ashly, A.; Hariharan, S. Influence of ultrasound on Avaram bark (Cassia auriculata) tannin extraction and tanning. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2014, 92, 1827–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Abert-Vian, M.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Dangles, O.; Chemat, F. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols (flavanone glycosides) from orange (Citrus sinensis L.) peel. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Segura-Carretero, A. Optimization of extraction method to obtain a phenolic compounds-rich extract from Moringa oleifera Lam leaves. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 66, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, R.S.; MacHado, M.T.C.; Martínez, J.; Hubinger, M.D. Ultrasound assisted extraction and nanofiltration of phenolic compounds from artichoke solid wastes. J. Food Eng. 2016, 178, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meullemiestre, A.; Petitcolas, E.; Maache-Rezzoug, Z.; Chemat, F.; Rezzoug, S.A. Impact of ultrasound on solid–liquid extraction of phenolic compounds from maritime pine sawdust waste. Kinetics, optimization and large scale experiments. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 28, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, C.; Fidel, T.; Leclerc, E.A.; Barakzoy, E.; Sagot, N.; Falguiéres, A.; Renouard, S.; Blondeau, J.P.; Ferroud, C.; Doussot, J.; et al. Development and validation of an efficient ultrasound assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) seeds. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 26, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, J.A.M.; Brito, L.F.; Caetano, K.L.F.N.; De Morais Rodrigues, M.C.; Borges, L.L.; Da Conceição, E.C. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of azadirachtin from dried entire fruits of Azadirachta indica A. Juss. (Meliaceae) and its determination by a validated HPLC-PDA method. Talanta 2016, 149, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Ma, X.; Sun, S.; Leng, F.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X. Extraction, purification, characterization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Piteguo fruit. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammi, K.M.; Jdey, A.; Abdelly, C.; Majdoub, H.; Ksouri, R. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of antioxidant compounds from Tunisian Zizyphus lotus fruits using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2015, 184, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Resurreccion, F.P. Electromagnetic basis of microwave heating. Dev. Packag. Prod. Use Microw. Ovens 2009, 3, 38e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delazar, A.; Nahar, L.; Hamedeyazdan, S.; Sarker, S.D. Microwave-assisted extraction in natural products isolation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 864, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina-Gabriela, G.; Emilie, D.; Gabriel, L.; Claire, E. Bioactive compounds extraction from pomace of four apple varieties. J. Eng. Stud. Res. 2012, 18, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Yedhu Krishnan, R.; Rajan, K.S. Microwave assisted extraction of flavonoids from Terminalia bellerica: Study of kinetics and thermodynamics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 157, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Tsubaki, S.; Ogawa, K.; Onishi, K.; Azuma, J. ichi Isolation of hesperidin from peels of thinned Citrus unshiu fruits by microwave-assisted extraction. Food Chem. 2010, 123, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirugnanasambandham, K.; Sivakumar, V. Microwave assisted extraction process of betalain from dragon fruit and its antioxidant activities. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2017, 16, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simić, V.M.; Rajković, K.M.; Stojičević, S.S.; Veličković, D.T.; Nikolić, N.; Lazić, M.L.; Karabegović, I.T. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of total polyphenolic compounds from chokeberries by response surface methodology and artificial neural network. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 160, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, F.L.; Fukuda, D.L.; Turbiani, F.R.B.; Garcia, P.S.; Petkowicz, C.L.D.O.; Jagadevan, S.; Gimenes, M.L. Extraction of pectin from passion fruit peel (Passiflora edulis F. Flavicarpa) by microwave-induced heating. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 38, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash Maran, J.; Sivakumar, V.; Thirugnanasambandham, K.; Sridhar, R. Microwave assisted extraction of pectin from waste Citrullus lanatus fruit rinds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petigny, L.; Périno, S.; Minuti, M.; Visinoni, F.; Wajsman, J.; Chemat, F. Simultaneous microwave extraction and separation of volatile and non-volatile organic compounds of boldo leaves. From lab to industrial scale. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 7183–7198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, P.; Verma, A.K.; Umaraw, P.; Mehta, N. Prospects in the meat industry: The new technology could be used for accelerated drying, curing, and other production steps. Fleischwirtschaft Int. J. Meat Prod. Meat Process. 2020, 1, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yogesh, K. Pulsed electric field processing of egg products: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Bhat, Z.F. Pulsed light and pulsed electric field-emerging non thermal decontamination of meat. Am. J. Food Technol. 2012, 7, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roselló-Soto, E.; Koubaa, M.; Moubarik, A.; Lopes, R.P.; Saraiva, J.A.; Boussetta, N.; Grimi, N.; Barba, F.J. Emerging opportunities for the effective valorization of wastes and by-products generated during olive oil production process: Non-conventional methods for the recovery of high-added value compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parniakov, O.; Lebovka, N.I.; Van Hecke, E.; Vorobiev, E. Pulsed electric field assisted pressure extraction and solvent extraction from mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussetta, N.; Vorobiev, E. Extraction of valuable biocompounds assisted by high voltage electrical discharges: A review. Comptes Rendus Chim. 2014, 17, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, E.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving the pressing extraction of polyphenols of orange peel by pulsed electric fields. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 17, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Farid, M.M. Pulsed electric field extraction of valuable compounds from white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 29, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, J.Y.; Lam, W.H.; Ho, K.W.; Voo, W.P.; Lee, M.F.X.; Lim, H.P.; Lim, S.L.; Tey, B.T.; Poncelet, D.; Chan, E.S. Advances in fabricating spherical alginate hydrogels with controlled particle designs by ionotropic gelation as encapsulation systems. Particuology 2016, 24, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, F.J.; Luengo, E.; Corral-Pérez, J.J.; Raso, J.; Almajano, M.P. Improvements in the aqueous extraction of polyphenols from borage (Borago officinalis L.) leaves by pulsed electric fields: Pulsed electric fields (PEF) applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 65, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, H.; Schulz, M.; Lu, P.; Knorr, D. Adjustment of milling, mash electroporation and pressing for the development of a PEF assisted juice production in industrial scale. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012, 14, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroian, M.; Escriche, I. Antioxidants: Characterization, natural sources, extraction and analysis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Labarca, V.; Plaza-Morales, M.; Giovagnoli-Vicuña, C.; Jamett, F. High hydrostatic pressure and ultrasound extractions of antioxidant compounds, sulforaphane and fatty acids from Chilean papaya (Vasconcellea pubescens) seeds: Effects of extraction conditions and methods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, O.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, H.S.; Hur, S.J. Overview of studies on the use of natural antioxidative materials in meat products. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2020, 40, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.P.; Singh, P.; Kumar, P. Drumstick (Moringa oleifera) as a food additive in livestock products. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, E.; Mes, J.; Wichers, H.J.; Jaime, L.; Mendiola, J.A.; Reglero, G.; Santoyo, S. Anti-inflammatory activity of the basolateral fraction of Caco-2 cells exposed to a rosemary supercritical extract. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, B.; Marques, A.; Ramos, C.; Neng, N.R.; Nogueira, J.M.F.; Saraiva, J.A.; Nunes, M.L. Chemical composition and antibacterial and antioxidant properties of commercial essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-H.; Su, J.-D.; Chyau, C.-C.; Sung, T.-Y.; Ho, S.-S.; Peng, C.-C.; Peng, R.Y. Supercritical fluid extracts of rosemary leaves exhibit potent anti-inflammation and anti-tumor effects. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellumori, M.; Michelozzi, M.; Innocenti, M.; Congiu, F.; Cencetti, G.; Mulinacci, N. An innovative approach to the recovery of phenolic compounds and volatile terpenes from the same fresh foliar sample of Rosmarinus officinalis L. Talanta 2015, 131, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulinacci, N.; Innocenti, M.; Bellumori, M.; Giaccherini, C.; Martini, V.; Michelozzi, M. Storage method, drying processes and extraction procedures strongly affect the phenolic fraction of rosemary leaves: An HPLC/DAD/MS study. Talanta 2011, 85, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Pradhan, S.R.; Das, A.; Nanda, P.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Das, A.K. Inhibition of lipid and protein oxidation in raw ground pork by Terminalia arjuna fruit extract during refrigerated storage. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Abraham, T.E. Studies on the antioxidant activities of cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) bark extracts, through various in vitro models. Food Chem. 2006, 94, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.R.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Tang, D.B.; Wang, J.Y. Protective effects of Momordica grosvenori extract against lipid and protein oxidation-induced damage in dried minced pork slices. Meat Sci. 2017, 133, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Khong, N.M.H.; Iqbal, S.; Ch’ng, S.E.; Younas, U.; Babji, A.S. Cinnamon bark deodorised aqueous extract as potential natural antioxidant in meat emulsion system: A comparative study with synthetic and natural food antioxidants. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 3269–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shan, B.; Cai, Y.Z.; Sun, M.; Corke, H. Antioxidant capacity of 26 spice extracts and characterization of their phenolic constituents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 7749–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Hobiger, S.; Jungbauer, A. Anti-inflammatory activity of extracts from fruits, herbs and spices. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, M. Anti-inflammatory phytochemicals: In vitro and ex vivo evaluation. Phytochemicals 2006, 1, 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino, K.; Higashi, N.; Koga, K. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities of oregano extract. J. Health Sci. 2006, 52, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, N.; Biswas, S.; Al-Dayan, N.; Alhegaili, A.S.; Sarwat, M. Antioxidant role of kaempferol in prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, D.; Tan, J.; Kuang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, G.; Xu, K.; Zou, Z.; Tan, G. Biflavonoids from Selaginella doederleinii as potential antitumor agents for intervention of non-small cell lung cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, A.; Legault, J.; Pichette, A.; Jean, L.; Bélanger, A.; Pouliot, R. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging potential of a Kalmia angustifolia extract and identification of some major compounds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavsan, Z.; Kayali, H.A. Flavonoids showed anticancer effects on the ovarian cancer cells: Involvement of reactive oxygen species, apoptosis, cell cycle and invasion. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chia, Y.-C.; Huang, B.-M. Phytochemicals from Polyalthia species: Potential and implication on anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and chemoprevention activities. Molecules 2021, 26, 5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Maati, M.F.A.; Mahgoub, S.A.; Labib, S.M.; Al-Gaby, A.M.A.; Ramadan, M.F. Phenolic extracts of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) with novel antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, A.; Syed, Q.A.; Khan, M.I.; Zia, M.A. Characterising and optimising antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of clove extracts against food-borne pathogenic bacteria. Int. Food Res. J. 2019, 26, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Multari, S.; Licciardello, C.; Caruso, M.; Martens, S. Monitoring the changes in phenolic compounds and carotenoids occurring during fruit development in the tissues of four citrus fruits. Food Res. Int. 2020, 134, 109228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic composition, antioxidant potential and health benefits of citrus peel. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E.; Madrid, Y. Citrus peels waste as a source of value-added compounds: Extraction and quantification of bioactive polyphenols. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, A.; Zarycka, E.; Yanovych, D.; Zasadna, Z.; Grzegorczyk, I.; Kłys, S. Mineral content of the pulp and peel of various citrus fruit cultivars. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 193, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieto, G.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Peñalver, R.; Ros-Berruezo, G.; Viuda-Martos, M. Valorization of citrus co-products: Recovery of bioactive compounds and application in meat and meat products. Plants 2021, 10, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, M.; Milatović, D.; Tešić, Ž.; Tosti, T.; Gašić, U.; Dojčinović, B.; Dabić Zagorac, D. Influence of rootstocks on the chemical composition of the fruits of plum cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 92, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysinghe, D.C.; Li, X.; Sun, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, C.; Chen, K. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities in different edible tissues of citrus fruit of four species. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, B.; Dahmoune, F.; Moussi, K.; Remini, H.; Dairi, S.; Aoun, O.; Khodir, M. Comparison of microwave, ultrasound and accelerated-assisted solvent extraction for recovery of polyphenols from Citrus sinensis peels. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, K.; Pristijono, P.; Golding, J.B.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Bowyer, M.C.; Scarlett, C.J.; Vuong, Q.V. Optimisation of aqueous extraction conditions for the recovery of phenolic compounds and antioxidants from lemon pomace. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 2009–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, C.Y.; Zhong, R.Z.; Tan, Z.L.; Han, X.F.; Tang, S.X.; Xiao, W.J.; Sun, Z.H.; Wang, M. Dietary inclusion of tea catechins changes fatty acid composition of muscle in goats. Lipids 2011, 46, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, I.; O’Grady, M.N.; Ansorena, D.; Astiasarán, I.; Kerry, J.P. Enhancement of the nutritional status and quality of fresh pork sausages following the addition of linseed oil, fish oil and natural antioxidants. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Cui, J.; Yin, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Z. Grape seed and clove bud extracts as natural antioxidants in silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) fillets during chilled storage: Effect on lipid and protein oxidation. Food Control 2014, 40, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, J.; Pohorly, J.E.; Kakuda, Y. Polyphenolics in grape seeds—biochemistry and functionality. J. Med. Food 2003, 6, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hygreeva, D.; Pandey, M.C.; Chauhan, O.P. Effect of high-pressure processing on quality characteristics of precooked chicken patties containing wheat germ oil wheat bran and grape seed extract. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silván, J.M.; Mingo, E.; Hidalgo, M.; de Pascual-Teresa, S.; Carrascosa, A.V.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J. Antibacterial activity of a grape seed extract and its fractions against Campylobacter spp. Food Control 2013, 29, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libera, J.; Latoch, A.; Wójciak, K.M. Utilization of grape seed extract as a natural antioxidant in the technology of meat products inoculated with a probiotic strain of LAB. Foods 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimitrijevic, M.; Jovanovic, V.S.; Cvetkovic, J.; Mihajilov-Krstev, T.; Stojanovic, G.; Mitic, V. Screening of antioxidant, antimicrobial and antiradical activities of twelve selected Serbian wild mushrooms. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 4181–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, S.; Djekic, I.; Klaus, A.; Vunduk, J.; Djordjevic, V.; Tomović, V.; Šojić, B.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; et al. The Effect of Cantharellus cibarius addition on quality characteristics of frankfurter during refrigerated storage. Foods 2019, 8, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramírez-Rojo, M.I.; Vargas-Sánchez, R.D.; Torres-Martínez, B.; Torres-Martínez, B.D.M.; Torrescano-Urrutia, G.R.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Sánchez-Escalante, A. Inclusion of ethanol extract of mesquite leaves to enhance the oxidative stability of pork patties. Foods 2019, 8, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goulas, V.; Georgiou, E. Utilization of carob fruit as sources of phenolic compounds with antioxidant potential: Extraction optimization and application in food models. Foods 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rathour, M.; Malav, O.P.; Kumar, P.; Chatli, M.K.; Mehta, N. Functional chevon rolls fortified with cinnamon bark and Aloe-vera powder extracts. Haryana Vet. 2019, 58, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jagtap, N.S.; Wagh, R.V.; Chatli, M.K.; Malav, O.P.; Kumar, P.; Mehta, N. Chevon meat storage stability infused with response surface methodology optimized Origanum vulgare leaf extracts. Agric. Res. 2020, 9, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, N.S.; Wagh, R.V.; Chatli, M.K.; Kumar, P.; Malav, O.P.; Mehta, N. Optimisation of extraction protocol for Carica papaya L. to obtain phenolic rich phyto-extract with prospective application in chevon emulsion system. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birla, R.; Malav, O.; Wagh, R.; Mehta, N.; Kumar, P.; Chatli, M. Storage stability of pork emulsion incorporated with Arjuna (Terminalia arjuna) tree bark extract. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2019, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, S.; Ahlawat, S.S. Development of buffalo meat rolls incorporated with aloe vera gel and arjun tree bark extract. Haryana Vet. 2015, 54, 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Guo, X. The application of clove extract protects chinesestyle sausages against oxidation and quality deterioration. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2017, 37, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, P.; Mehta, N.; Malav, O.P.; Kumar Chatli, M.; Rathour, M.; Kumar Verma, A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial efficacy of watermelon rind extract (WMRE) in aerobically packaged pork patties stored under refrigeration temperature (4 ± 1 °C). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2018, 42, e13757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, R.V.; Chatli, M.K. Response surface optimization of extraction protocols to obtain phenolic rich antioxidant from sea buckthorn and their potential application into model meat system. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, A.K.; Rajkumar, V.; Verma, A.K.; Swarup, D. Moringa oleiferia leaves extract: A natural antioxidant for retarding lipid peroxidation in cooked goat meat patties. Int. J. food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, M.; Naveena, B.M.; Vaithiyanathan, S.; Sen, A.R.; Sureshkumar, K. Effect of incorporation of Moringa oleifera leaves extract on quality of ground pork patties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 3172–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansour, E.H.; Khalil, A.H. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of some plant extracts and their application to ground beef patties. Food Chem. 2000, 69, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Gu, W.; Zhang, J.; Chu, Y.; Ye, X.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J. Effects of chitosan, aqueous extract of ginger, onion and garlic on quality and shelf life of stewed-pork during refrigerated storage. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-López, J.; Sevilla, L.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Navarro, C.; Marín, F.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A. Evaluation of the antioxidant potential of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis L.) and Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extracts in cooked pork meat. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarpat, A.; Turhan, S.; Ustun, N.S. Effects of hot-water extracts from myrtle, rosemary, nettle and lemon balm leaves on lipid oxidation and colour of beef patties during frozen storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2008, 32, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rababah, T.M.; Ereifej, K.I.; Alhamad, M.N.; Al-Qudah, K.M.; Rousan, L.M.; Al-Mahasneh, M.A.; Al-u’datt, M.H.; Yang, W. Effects of green tea and grape seed and TBHQ on physicochemical properties of baladi goat meats. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, M.D.; Auqui, M.; Martí, N.; Linares, M.B. Effect of two different red grape pomace extracts obtained under different extraction systems on meat quality of pork burgers. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 2238–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-A.; Choi, J.-H.; Choi, Y.-S.; Han, D.-J.; Kim, H.-Y.; Shim, S.-Y.; Chung, H.-K.; Kim, C.-J. The antioxidative properties of mustard leaf (Brassica juncea) kimchi extracts on refrigerated raw ground pork meat against lipid oxidation. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; He, J.; Ban, X.; Zeng, H.; Yao, X.; Wang, Y. Antioxidant activity of bovine and porcine meat treated with extracts from edible lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) rhizome knot and leaf. Meat Sci. 2011, 87, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogesh, K.; Jha, S.N.; Yadav, D.N. Antioxidant Activities of Murraya koenigii (L.) spreng berry extract: Application in refrigerated (4 ± 1 °C) stored meat homogenates. Agric. Res. 2012, 1, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, A.K.; Rajkumar, V.; Nanda, P.K.; Chauhan, P.; Pradhan, S.R.; Biswas, S. Antioxidant efficacy of litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) pericarp extract in sheep meat nuggets. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, A.I.; Petrón, M.J.; Adámez, J.D.; López, M.; Timón, M.L. Food by-products as potential antioxidant and antimicrobial additives in chill stored raw lamb patties. Meat Sci. 2017, 129, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Jebin, N.; Saha, R.; Sarma, D.K. Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of kordoi (Averrhoa carambola) fruit juice and bamboo (Bambusa polymorpha) shoot extract in pork nuggets. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ramella, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Zamuz, S.; Valdés, M.E.; Moreno, D.; Balcázar, M.C.G.; Fernández-Arias, J.M.; Reyes, J.F.; Franco, D. The Antioxidant effect of Colombian berry (Vaccinium meridionale Sw.) extracts to prevent lipid oxidation during pork patties shelf-life. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasukamonset, P.; Kwon, O.; Adisakwattana, S. Oxidative stability of cooked pork patties incorporated with clitoria ternatea extract (blue pea flower petal) during refrigerated storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Florio Almeida, J.; dos Reis, A.S.; Heldt, L.F.S.; Pereira, D.; Bianchin, M.; de Moura, C.; Plata-Oviedo, M.V.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Ribeiro, I.S.; da Luz, C.F.P.; et al. Lyophilized bee pollen extract: A natural antioxidant source to prevent lipid oxidation in refrigerated sausages. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 76, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldin, J.C.; Michelin, E.C.; Polizer, Y.J.; Rodrigues, I.; de Godoy, S.H.S.; Fregonesi, R.P.; Pires, M.A.; Carvalho, L.T.; Fávaro-Trindade, C.S.; de Lima, C.G.; et al. Microencapsulated jabuticaba (Myrciaria cauliflora) extract added to fresh sausage as natural dye with antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Meat Sci. 2016, 118, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munekata, P.E.S.; Calomeni, A.V.; Rodrigues, C.E.C.; Fávaro-Trindade, C.S.; Alencar, S.M.; Trindade, M.A. Peanut skin extract reduces lipid oxidation in cooked chicken patties. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeletti, M.; Sparapani, L. Process for Producing a Grape Seed Extract Having a Low Content of Monomeric Polyphenols. U.S. Patent 20,070,134,354, A1 12 July 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Plant Extracts Market Size and Forecast. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/global-plant-extracts-market-size-and-forecast-to-2025/ (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Beya, M.M.; Netzel, M.E.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Smyth, H.; Hoffman, L.C. Plant-based phenolic molecules as natural preservatives in comminuted meats: A review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Graciá, C.; González-Bermúdez, C.A.; Cabellero-Valcárcel, A.M.; Santaella-Pascual, M.; Frontela-Saseta, C. Use of herbs and spices for food preservation: Advantages and limitations. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 6, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, C.J.; Orabueze, I.; Okorie, N.H. Antioxidants properties of natural and synthetic chemical compounds: Therapeutic effects on biological system. Acta Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 3, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorný, J. Are natural antioxidants better—And safer—Than synthetic antioxidants? Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2007, 109, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | MAE | SFE | UAE | DIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Used along with traditional extraction methods to improve the extraction process | Very fast process | Used along with traditional extraction methods to improve extraction process | Rapid extraction |

| Solvent consumption | A small amount of solvent required | Very little amount of organic solvent or no solvent due to re-use | A small amount of solvent | Steam-driven progress with rapid depressurization |

| Solvent residue | Less solvent residue | No solvent residue due to phase separation on depressurization | Less solvent residue | Very low |

| Suitability/Applicability | Applicable for limited samples | Minimal application for a selected compound | High versatility and suitability | Used for sample pre-treatment process |

| Selectivity | Non-selectivity, extraction of a range of compounds | High selective for extraction of a small number of compounds | Non-selective extracts a range of compound | Non-selective extracts a range of compound |

| Processing conditions | High temperature and pressure | Not harsh conditions for SC CO2 | Not harsh conditions | High temperature |

| Suitability for heat-labile compounds | Not suitable | Suitable to preserve the activity of heat-labile compounds | Suitable | Not suitable for heat-labile compounds |

| Energy consumption | High | Low due to re-use of solvent | Relatively low | High |

| Capital cost | Low initial capital cost | Very high | Lower capital cost | Very high |

| Technical workforce | Simple process | Needs very high technical workforce | Simple and easier operations | Needs high technical workforce |

| Plant Material | Processing Protocol (Temp, Pressure, Flow Rate) | Remark | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propane as supercritical fluid | |||

| Flaxseed | 30–45 °C, 80–120 bar | 28% higher yield of flaxseed oil with better composition, purity, and oxidative stability as compared with convention chloroform-methanol-water Soxhlet extraction | [47] |

| Perilla | 40–80 °C, 80–160 bar, 1.0 cm3/min flow rate | Higher extraction yield of perilla oil with oxidative stability | [48] |

| Crambe seed | 79.85 °C, 160 bar | The temperature has a vital role in affecting yield, less than 2% free fatty acids in the extract | [49] |

| Pequi pulp | 30–40 °C, 50–150 | 43% higher yield of oil at 15 MPa | [50] |

| Canola seed | 30–60 °C, 80–120 bar along with SC CO2 (40–60 °C and 200–250 bar) | Propane SFE faster than CO2 SFE | [51] |

| Sesame seed | 30–40 °C, 20–120 bar along with SC CO2 (30–40 °C, 190–250 bar) | Extract quality same with both solvents, and temperature and pressure have an important role. | [52] |

| Sunflower seed | Propane and CO2 | High concentration of tocopherol in the oil | [53] |

| LPG as supercritical fluid | |||

| Rice bran | Compressed LPG and SC CO2 | LPG decreased extraction time and save energy of re-compression | [54] |

| Elaeis guineensis | Compressed LPG | Advantages in terpene extraction with improve speed and reducing cost | [55] |

| Plant Source | Pre-Treatment | SC CO2 Protocols | Extract Yield | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microwave-assisted SFE (MASFE) | ||||

| Moringa oleifera seeds | 100 W for 30 s | 40 °C, 300 bar | 11% higher yield | [64] |

| Enzymatic-assisted SFE (EASFE) | ||||

| Black pepper | amylase | 60 °C, 300 bar, 2 L/min flow | 53% increase yield with 46% higher piperine-enriched extract | [65] |

| Pomegranate peel | cellulase, pectinase and protease (2:1:1) | 55 °C, 33 bar, 30–120 min, 2 g/min flow rate | vanillic acid (108.36 mu g/g), ferulic acid (75.19 mu g/g), and syringic acid (88.24 mu g/g) content in the extract | [66] |

| Black tea leftover | kemzyme (2.8% w/w at 45 °C, pH 5.4 for 98 min) | 55 °C, 300 bar, 0.2–2 g/min flow rate, 30–120 min, ethanol as co-solvent | five-fold increase in extract yield | [67] |

| Tomato peel | glycosidase | 500 bar, 86 °C, 4 mL/min | three-fold increase in lycopene yield | [68] |

| Ultrasound-assisted SFE (UASFE) | ||||

| Zinger | 300 W, 20 kHz | 40 °C, 160 bar, 4–8 mm particle size, | 30% higher yield | [71] |

| Clove | 185 W | 32 °C, 95 bar, 0.233 × 10−4 flow rate, 115 min | 11% higher clove oil with 1.2 times higher α-humelene | [72] |

| Korean perilla | 750 W, 25 kHz for 125 s | 25 °C, 100 bar, 1 h; ethanol as co-solvent | 53% increase of luteolin and 144% increase of apigenin | [73] |

| Capsicumbaccatum | 600 W | 40 °C, 250 bar 1.7569 × 10−4 kg/s flow rate, 80 s | 45% higher yield with 12% increase in capsaicinoid | [74] |

| Capsicumfrutescens | 360 W | 40 °C, 150 bar, 1.673 × 10−4 flow rate, 1 h | 77% higher yield | [75] |

| Hedyotis diffusa | 185 W | 55 °C, 245 bar, 95 s | 11–14% higher yield | [76] |

| Almond oil | 20 kHz | 55 °C, 280 bar, 55.6 × 10−4 flow rate, 510 s | 24% higher yield | [77] |

| Plant Source | Extraction Medium | Extraction Protocols | Bioactive Compounds in the Extract | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roasted peanuts | SC CO2 | 96 bar, 50 °C, fluid density-0.35 g/mL | 74 flavor compounds (8–86 µg/kg) as hexanol, benzene acetaldehyde, methyl and ethyl pyrazines, methyl pyrrole, ethyl pyrazine, methyl pyrazines identified in the extract | Increasing roasting temperature and time significantly improved flavor compounds, with carboxylic acid becoming the most prominent | [38,39,79,80,81] |

| Coffee beans | SC CO2, 9.5% ethanol | 200 bar, 100 °C | 79% efficiency for acrylamide without affecting caffeine content in coffee | Temperature variation affected the extraction efficiency | [82] |

| Cumin | SC CO2, toluene as static modifier | 550 bar, 100 °C | Cumin essential oil concentration ranging from 1.74 to 3.51% (v/w) | Significantly decreased the extraction time from 8 h to 2 h | [83] |

| Turmeric | SC CO2, ethanol, isopropyl alcohol | In a fixed-bed extractor 300 bar, 30 °C | Increased curcuminoid content to 0.72% at 50% co-solvent without compromising extract yield percent (10%) | The best solvent mixture was 50% with 1.8 bed height/diameter ratio | [84] |

| Hyssop | Methanol (1.5% v/v) | 101.3 bar, 55 °C, 30 min dynamic and 35 static time for sabinene | Sabinene (4.2–17.1%, w/w), iso-pinocamphone (0.9–16.5%), and pinocamphone (0.7–13.6%) | Composition of essential oil varies with extraction protocols | [85] |

| Black pepper | SC CO2 | 75–150 bar, 30–50 °C, particle size (0.5, 0.75 mm and whole berries) | Smaller particle size increase yield, Higher sesquiterpene concentration in SFE | Increase pressure and decrease temperature increase extract yield | [86] |

| Long pepper | SC CO2 with 10% ethanol, 10% methanol | 400 bar, 40–70 °C | Piperovatine (0.93%) > palmitic acid > pentadecane > pipercallosidine | Drying leaves reduced amide concentration, the highest yield of piperovaltine by taking fresh leaves | [87] |

| Orange oil | SC CO2 | 131 bar, 35 °C, 2 kg/h flow rate | Increase concentration of oxygenated flavoring compounds (20 times more decanal) | Low temperature and flow rate improve fractionalization | [88] |

| Hop | CO2, ethanol, and water | 111. 4 bar, 50 °C, 0.5 g/mL density | Highly concentrated oxygenated sesquiterpenoids | Reducing bitterness by decreasing lupulone and humulone | [89] |

| Eucalyptus globus | SC CO2, ethanol (0–0.5%) | 200 bar, 40 °C | 1.2% extraction yield, 50% concentration of triterpenic acid (5.1 g/kg of bark) with methyl 3-hydroxyolean-18-en-28-oate most abundant | About 80% more yield than conventional Soxhlet extraction method | [90] |

| Polygala senega and Acorus tatarinowii | SC CO2 | 450 bar, 35 °C, 2 h | 24 compounds with 6 compounds (eugenol, beta-asarone, ethyl oleate, 1,2,3-trimethoxy-5(2-propenyl)-benzene, 6-octadecenoic acid, and 9–12-octadecadienoic acid) had more than 1.0% | Herb combinations increase the bioactive compounds with less compounds with one benzene ring compounds | [91,92] |

| Frankincense (Boswellia carterii) | SC CO2 | 200 bar, 55 °C, 94 min | The volatile oil contains 80% octyl acetate | SC CO2 extraction as the optimum extraction method | [93] |

| Cannabis sativa var. indica | Ultrasound extraction with cyclohexane and isopropanol solvent | 100 bar, 35 °C, 1 mL/min | Isopropanol/cyclohexane 1:1 mixture, cycles 3 s, amplitude (80%) and sonication time (5 min) at 100 bar, 35 °C, 1 mL/min, no co-solvent for the terpenes and 20% of ethanol for the cannabinoids | Three monoterpenes and three cannabinoids were quantified in the ranges of 0.006–6.2 μg/g and 0.96–324 mg/g | [94] |

| Croton zehntneri | SFE CO2 | 66.7 bar, 15 °C | €-anethole α-muurolene, methyl chavicol or estragole, germacrene | Maximum solubility and yield at 20 °C | [95,96] |

| Bay laurel Laurus nobilis berries | SC CO2 | 90–250 bar 40 °C | €-β-ocimene (20.9%), α-pinene (4.2%),1,8-cineole (8.8%), β-longipinene (7.1%), α-bulnesene (3.5%) | 15% yield, extraction at 250 bar produced an odorless liquid fraction with dominant triacylglycerols | [97] |

| Spearmint (Mentha spicata) | SC CO2, ethanol and ethyl acetate | 50 °C and 300 bar | Carvone, 1,8-cineole, pulegone | Ethanol co-solvent has a maximum yield | [98] |

| SC CO2 | 90 bar, 45 °C, 5 mL/s flow rate, 120 min dynamic time; 90 bar, 35 °C, 250 μm, 1 mL s−1, and 30 min | 500 μm particle size has highest yield | 2.03% extract yield and CO2 concentration 0.033 mg/mL | [99] | |

| Ocimum basilicum (sweet basil) | Hydrodistillation and SC CO2 | 100–120 bar, 40–50 °C | Four times higher percentage of 1,8-cineole, 5–8 times, linalool, 1-2-fold eugenol, 28-fold germacrene | Higher t-cadinol and sesquiterpenes in essential oil | [100] |

| Clove basil (O. gratissimum | SC CO2 | 90–128 bar, 25–50 °C; 0.05–0.35 g/min flow rate | Eugenol (35–60%) and β-selinene (11.5–14.1%) | Solvent-to-feed ratio, 16:21; finely ground particle improves yield | [101] |

| Tomato skin and seed | SC CO2 | 300 bar, 60 °C, 0.16, 0.27, 3–8 h, 0.41 g/min flow rate | 86% recovery of E-lycopen | Solvent to solid ratio 220 g CO2/g | [102] |

| Passion fruit bagasse | SC CO2 | 50–60 °C, 170–260 bar, 20.64 g/min flow rate | 1.5- and 5.8-times higher tocopherols and carotenoids | SFE applied in the second stage improved the efficiency | [103] |

| Winter melon | SC CO2, ethanol | 244 bar, 46 °C, 10 g/min flow rate, 97 min, 0.5 L extractor dimension | 176 mg extract/g dried sample | Antioxidant activity of extract higher than obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction or Soxhlet extraction | [104] |

| Cannabis sativa | SC CO2 | 300–400 bar, 40–60 °C, 1.94 kg/h flow rate | 125.37 µg/g tocopherol in extract | 2–3 times higher gamma-tocopherol content and higher alpha-tocopherol | [105] |

| Carica papaya fruit | SC CO2 | 200 bar, 80 °C, 16.45 mL/min flow rate, 3 h | Benzyl isothiocyanate (anthelmetic), carpaine and pseudocarpaine | Solvent/solid ratio 1180.4 g CO2/g | [106] |

| Camelina sativa | SC CO2 | 450 bar, 70 °C, 1 L/m flow rate, 510 min | Alpha-linoleic, oleic, eicosaenoic and erusic acids, higher phytosterol content | Solvent/Solid Ratio (gCO2/g)-16.14 | [107] |

| Quinoa seed | SC CO2 | 185 bar, 130 °C, 0.175–0.45 g/min flow rate, 3 h, 1.2 mL extractor size | Four-fold increase in tocopherol content (336 mg/100 g oil) with SFE as compared with extraction with hexane | Solvent/Solid Ratio (gCO2/g)-8.02 to 67.5 | [108] |

| Crocus sativus | SC CO2 | 349 bar, 44.9 °C, 10.1 L/h flow rate, 150.2 min | Extraction yield-10.94 g/kg with large amount of unsaturated fatty acid | Solvent/solid Ratio (gCO2/g) 1377.27 | [109] |

| Eugenia uniflora | SC CO2 ethanol (polarity 5.2) and water (polarity-9.0) | 400 bar, 60 °C, 2.4 g/min flow rate, 6 h | Trans-caryophyllene (14.18%), germacrenos bicyclogermacrene (40.75%), Selina epoxide (27.7%) | Solvent/solid Ratio (gCO2/g) 20.09 sequential extraction process most effective | [110] |

| Moringa oleifera | SC CO2 | 500 bar, 60 °C, 2 mL/min flow rate, 2 h | Selective extraction of 12 bioactive compounds in SFE | Solvent/Solid Ratio (gCO2/g) 37.85 | [111] |

| 350 bar, 30 °C, 20 kg/h flow rate, 5 h, 2 L extractor diameter | Oleic acid (72.26–74.72%), sterol and tocopherol rich extract | Solvent/solid Ratio (gCO2/g) 1329.77 | [112] | ||

| Microwave pre-treatment (100 W, 30 s) followed by SC CO2 | 300 bar, 40 °C, 166.7 flow rate, 210 min, extractor dimensional 1 L | Microwave pre-treatment improves the extraction yield, polyunsaturated fatty acids, oil yield-35.28% w/w | Solvent/Solid Ratio (gCO2/g) 921.23–1000.2 | [64] | |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | SC CO2 | 210 bar, 48 °C, 333.33 g/min flow rate, 1.5 h, extractor dimension-100 mL | Phenol content: 5.48 mg GAE/g (dry weight) with 0.135 g dry weight content | Solvent/Solid Ratio (gCO2/g) 222,220 | [113] |

| Vine/Humulus lupulus | SC CO2, ethanol, ethyl acetate and compressed propane | 250 bar, 80 °C, compressed propane at 100 bar, 20 °C | Yield increases to 2.7% in compressed propane and 10.1% in SC CO2-ethyl acetate | Ethyl acetate as a co-solvent improve extraction yield and increases the concentration of bioactive compounds | [114] |

| Catharanthus roseus | SC CO2, ethanol | 159 bar, Flow rate-0.3 mL/min, 8 min | Vincristine (size 5–200 nm) rich extract | Improve bioavailability | [115] |

| Cacao pod husk | SC CO2, ethanol (13.7%) | 299 bar, 60 °C | 0.52% extract yield having 12.97 mg GAE/g extract phenolic contents | Extract enriched in phenolic compounds, green technology | [116] |

| Yacon leaves | SC CO2, ethanol | 250 bar, 70 °C, ethanol to solid ratio-3:1 | High amount of total phenolic compounds and highest ω-6/ω-3 fatty acids ratios | Major unsaturated fatty acid in extract-gamma-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid and linoleic acid | [117] |

| Tilia flower | SC CO2, ethanol (5–10%) | 220 bar, 65 °C, 15 min | Tiliroside as main flavonoids in the extract | Increase in temperature and pressure increase deficiency | [118] |

| Odontonema strictum leaves | SC CO2, ethanol | 200 bar, 270 min | Three-fold increase in total flavonoid recovery containing 5 major flavonoids | The temperature does not affect extraction | [119] |

| Sage leaves | SC CO2 | 150–200 bar, 25 °C, 90 min | High content of α-humulene, viridiflorol, and manool at low pressure (0.24–0.73%) | Pressure as the most critical parameter | [120] |