Sweet Potato Is Not Simply an Abundant Food Crop: A Comprehensive Review of Its Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and the Effects of Processing †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Bioactive Compounds in Sweet Potato Tubers

2.1. (Poly)phenols

2.1.1. Total (Poly)phenol Content

| Origin | Sample Extraction | Analytical Method | Phytochemical | Amount of Phytochemical | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | Methanol (80%) | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | ~1.4 mg CA/g FW | [9] |

| Methanol (80%) | pH-differential | TAC | <0.1 mg anthocyanins/g FW | ||

| USA | Ethanol (80%) | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | ~0.1 mg CA/g FW | [20] |

| Bangladesh | Acetone:water (7:3, v/v) | Folin-Ciocalteu | TPC | 94.3 to 136.1 mg GA/100 g FW | [13] |

| Kenya | Methanol (80%) | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | TPC mg GA/100 g DW:

| [18,25] |

| Aluminum chloride | TPC | TPC mg catechin/100 g DW:

| |||

| USA | Ethanol (80%) | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | 57.1 to 78.6 mg CA/100 g FW | [20] |

| HPLC-DAD and LC-MS/MS | Phenolic acids: chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, di-O-caffeoylquinic acids | Phenolic acids mg/100 g FW:

| |||

| Pakistan | Ethyl acetate | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | 319.8 μg GA/mg DE | [26] |

| Methanol | 262.6 μg GA/mg DE | ||||

| Ethyl acetate | Aluminum chloride | TFC | 208.8 μg quercetin/mg DE | ||

| Methanol | 177.8 μg quercetin/mg DE | ||||

| Korea | Methanol (50%) withn1.2 M HCl at 80 °C | HPLC system | Quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol, luteolin, ferulic, p-coumaric, p-hydroxybenzoic, sinapic, syringic, and vanillic acids. | Flavonoids: 127.1 µg/g DW (Quercetin: 59.9, myricetin: 39.8, kaempferol: 18.9, luteolin: 8.5) Phenolic acids: 71.1 µg/g DW (p-hydroxybenzoic acid:7.8, vanillic acid 7.9, syringic acid:3.8, p-coumaric:11.9, ferulic acid:24.6, sinapic acid:15.2) | [27] |

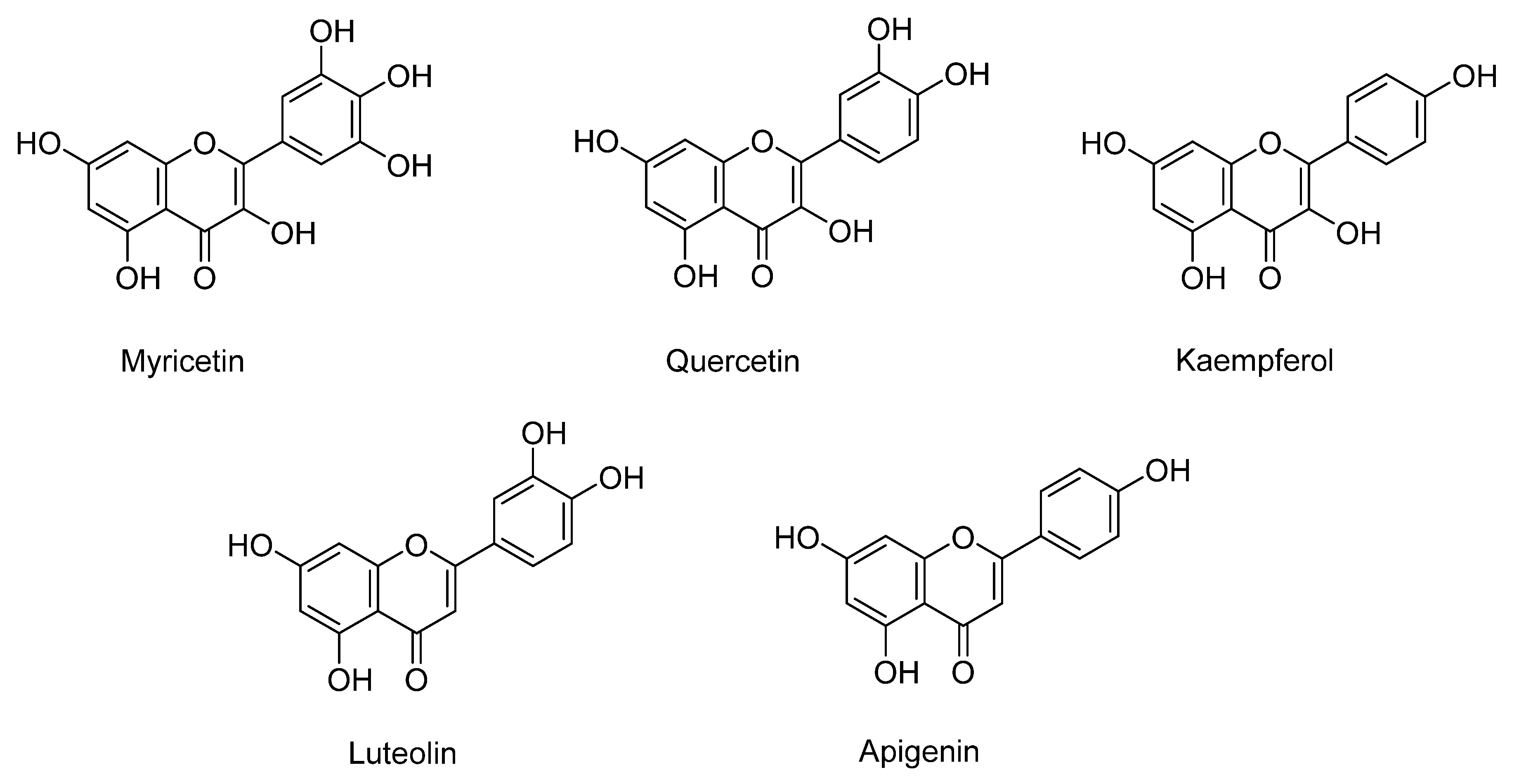

2.1.2. Flavonoids

2.1.3. Anthocyanins (In Purple Sweet Potato)

2.1.4. Phenolic Acids

2.1.5. Isolation, Identification, and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Sweet Potatoes

2.2. Carotenoids

2.3. Other Phytochemicals

| Origin | Sample Extraction | Analythical Method | Phytochemical | Amount of Phytochemical | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carotenoids | |||||

| USA | Hexane-acetone (1:1) | Reverse-phase HPLC | β-Carotene | ~122.0 µg/g FW, ~18.2 µg/g FW (light-orange) | [9] |

| Bangladesh | Hexane-acetone (1:1) | Spectrophotometry | TC | 0.38 to 7.24 µ * | [13] |

| Reverse-phase HPLC | TC | 19.3 to 61.9 µ * | |||

| trans-β-Carotene | 76.6 to 96.5 µ * | ||||

| cis-β-Carotene: | 3.5 to 23.4 µ * | [52] | |||

| Brazil | Acetone-petroleum ether. Petroleum ether: diethyl ether (1:1) | Reverse-phase HPLC | trans-β-Carotene | Raw: 79.1 to 128.5 mg *, boiled: 68.9 to 133.3 mg *, roasted: 64.6 to 127.0 mg *, steamed: 69.4 to 131.0 mg *, flour: 45.4 to 79.7 mg * | [19] |

| 13-cis-β-Carotene | Raw: 9.3 to 9.6 mg *, boiled: 4.3 to 8.6 mg *, roasted: 4.3 to 11.1 mg *, steamed: 7.1 to 8.5 mg *, flour: 2.7 to 4.7 mg * | ||||

| 9-cis-β-Carotene | Raw: 4.9 to 6.1 mg *, boiled: 3.9 to 6.0 mg *, roasted: 3.8 to 5.5 mg *, steamed: 5.2 to 7.4 mg *, flour: 1.5 to 2.1 mg * | ||||

| 5,6-Eepoxy-β-carotene | Raw: 7.0 to 11.3 mg *, boiled: 7.8 to 13.1 mg *, roasted: 7.0 to 9.6 mg *, steamed: 7.6 to 15.4 mg *, flour: 3.8 to 6.5 mg * | ||||

| Lutein | Raw: 0.1 to 0.4 mg *, boiled: 0.2 to 0.4 mg *, roasted: 0.1 to 0.6 mg *, steamed: 0.1 to 1.1 mg *, flour: 0.1 to 0.3 mg * | ||||

| Zeaxanthin | Raw: 0.1 to 0.2 mg *, boiled: 0.1 to 0.3 mg *, roasted: 0.1 to 0.2 mg *, steamed: 0.1 to 0.6 mg *, flour: 0.1 to 0.2 mg * | ||||

| Kenya | Methanol and tetrahydrofuran | Reverse-phase HPLC | Lutein | 0.01 to 0.1 mg * | [18,25] |

| Zeaxanthin | 0.02 to 0.5 mg * | ||||

| β-Xanthin | 0.1 to 0.5 mg * | ||||

| 13-cis-β-Carotene | 0.05 to 0.4 mg * | ||||

| All trans β-Carotene | 2.6 to 18.2 mg * | ||||

| β-9-cis-β-Carotene | 0.05 to 0.4 mg * | ||||

| Korea | Ethanol (0.1% ascorbic acid) | HPLC system | TC | 93.4 µg ** | |

| Lutein | 0.15 µg ** | [27] | |||

| α-Carotene | 0.44 µg ** | ||||

| (all E)-β-Carotene | 68.74 µg ** | ||||

| (9Z)-β-Carotene | 1.45 µg ** | ||||

| (13Z)-β-Carotene | 22.64 µg ** | ||||

| India | Hexane-acetone (6:4) | HPLC | TC | 7.47 to 15.47 mg/100 g FW | |

| β-Carotene | 5.85 to 13.63 mg/100 g FW | [46] | |||

| Phytosterols | |||||

| China | Ethanol (70%) | HPLC system | Daucosterol linolenate | 0.05 to 0.2 mg ** | [50] |

| Acetone-petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol (1:1) | Daucosterol linoleate | 0.2 to 0.5 mg ** | |||

| Daucosterol palmitate | 0.3 to 0.6 mg ** | ||||

| Other phytochemicals | |||||

| Kenya | Water | UV spectrophotometry | Tannic acid | 0.04 to 0.13 g * | [25] |

| Water | HPLC | Oxalic acid | 0.003 to 0.132 g * | ||

| NS | ELISA kit | Phytic acid | 0.05 to 0.42 g * | ||

| Color of Sweet Potato Flesh (Origin) | Sample Extraction | Analythical Method | Phytochemical | Amount of Phytochemical | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purple (USA) | Hexane–acetone (1:1) | Reverse-phase HPLC | β-Carotene | ~22.5 µg/g FW, ~50.6 µg/g FW (light purple) | [9] |

| Purple (Korea) | Ethanol (0.1% ascorbic acid) | HPLC system | TC | −2.22 µg ** | [27] |

| Lutein | −0.28 µg ** | ||||

| Zeaxanthin | −0.11 µg ** | ||||

| (all E)-β-Carotene | −1.53 µg ** | ||||

| (9Z)-β-Carotene | −0.02 µg ** | ||||

| (13Z)-β-Carotene | −0.28 µg ** | ||||

| Yellow (USA) | Hexane–acetone (1:1) | Reverse-phase HPLC | β-Carotene | ~−1.9 µg/g FW | [9] |

| Yellowish cream (Bangladesh) | Acetone:petroleum ether | Spectrophotometry Reverse pase HPLC | TC | −3.3 to 5.6 µ * | [52] |

| trans--β-Carotene | −83.6 to 84.3 µ * | ||||

| cis--β-Carotene: | −13.4 to 15.7 µ * | ||||

| White (USA) | Hexane–acetone (1:1) | Reverse-phase HPLC | β-Carotene | −0.2 µg/g FW | [9] |

| White (Bangladesh) | Acetone:petroleum ether | Spectrophotometry Reverse pase HPLC | TC | −1.0 µ * | [52] |

| White (Korea) | Ethanol (0.1% ascorbic acid) | HPLC system | TC | −1.37 µg ** | [27] |

| Lutein | −0.27 µg ** | ||||

| Zeaxanthin | −0.03 µg ** | ||||

| α-Carotene | −0.01 µg ** | ||||

| (all E)-β-Carotene | −0.83 µg ** | ||||

| (9Z)-β-Carotene | −0.09 µg ** | ||||

| (13Z)-β-Carotene | −0.14 µg ** |

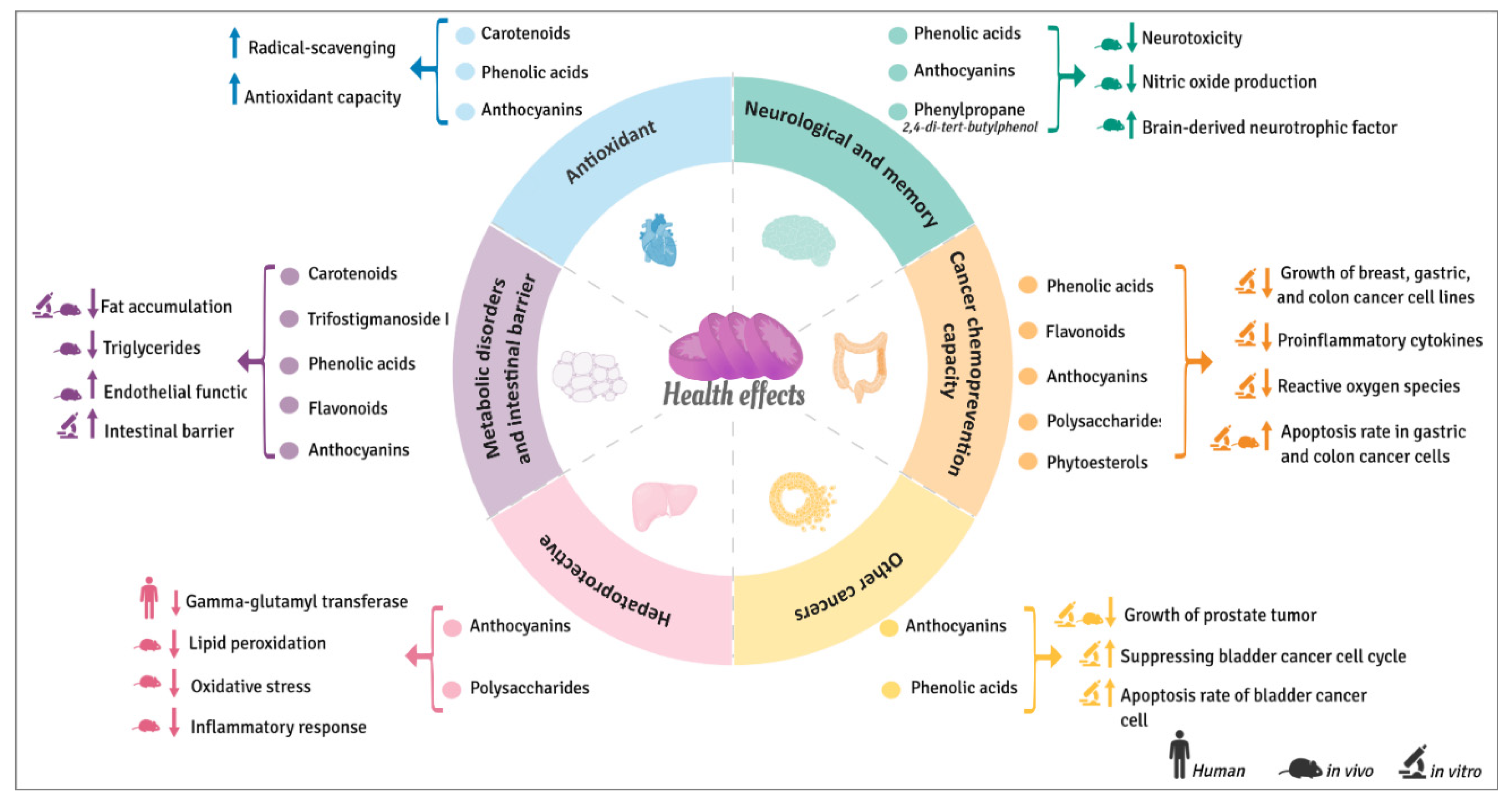

3. Beneficial Health Effects of Sweet Potatoes

3.1. Antioxidant Properties

3.2. Hepatoprotective Effects

3.3. Cognitive and Memory Improvement

3.4. In Vitro and In-Vivo Cancer Chemoprevention Capacity

3.4.1. Breast Cancer

3.4.2. Colon Cancer

3.4.3. Other Cancers

3.5. Metabolic Disorders and Intestinal Barrier Function

4. Effect of Sweet-Potato Processing on Phenolic Compounds

4.1. Drying Treatments

4.1.1. Hot-Air Drying, Microwave Drying, and Vacuum-Freeze Drying

4.1.2. Spray Drying

4.2. Pretreatments

4.2.1. Ultrasound

4.2.2. Vacuum Impregnation

4.3. Cooking Techniques

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jung, J.-K.; Lee, S.-U.; Kozukue, N.; Levin, C.E.; Friedman, M. Distribution of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidative Activities in Parts of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batata L.) Plants and in Home Processed Roots. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovell-Benjamin, A.C. Sweet Potato: A Review of Its Past, Present, and Future Role in Human Nutrition. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2007, 52, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, P.-H.; Yeh, C.-T.; Yen, G.-C. Anthocyanins Induce the Activation of Phase II Enzymes through the Antioxidant Response Element Pathway against Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 9427–9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cao, G.; Prior, R.L. Oxygen Radical Absorbing Capacity of Anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Choi, S.; Kang, J.-H.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Trifostigmanoside I, an Active Compound from Sweet Potato, Restores the Activity of MUC2 and Protects the Tight Junctions through PKCα/β to Maintain Intestinal Barrier Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanraj, R.; Sivasankar, S. Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam)-A Valuable Medicinal Food: A Review. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, U.K.; Sharma, A. Functional Foods and Their Benefits: An Overview. J. Nutr. Health Food Eng. 2017, 7, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Cai, W.; Xu, B. Profiles of Phenolics, Carotenoids and Antioxidative Capacities of Thermal Processed White, Yellow, Orange and Purple Sweet Potatoes Grown in Guilin, China. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2015, 4, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teow, C.C.; Truong, V.-D.; McFeeters, R.F.; Thompson, R.L.; Pecota, K.V.; Yencho, G.C. Antioxidant Activities, Phenolic and β-Carotene Contents of Sweet Potato Genotypes with Varying Flesh Colours. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Aldini, G.; Carini, M.; Chen, C.-Y.O.; Chun, H.-K.; Cho, S.-M.; Park, K.-M.; Correa, C.R.; Russell, R.M.; Blumberg, J.B. Characterisation, Extraction Efficiency, Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Phytonutrients in Angelica Keiskei. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, K.-H.; Chao, P.-Y.; Lin, H.-H.; Huang, M.-Y. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidants, and Health Benefits of Sweet Potato Leaves. Molecules 2021, 26, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, S.; Chauhan, V.B.S.; Pati, K.; Bansode, V.; Nedunchezhiyan, M.; Verma, A.K.; Monalisa, K.; Naik, P.K.; Naik, S.K. Biology and Biotechnological Aspect of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.): A Commercially Important Tuber Crop. Planta 2022, 256, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Rana, Z.; Islam, S. Comparison of the Proximate Composition, Total Carotenoids and Total Polyphenol Content of Nine Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato Varieties Grown in Bangladesh. Foods 2016, 5, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurata, R.; Sun, H.N.; Oki, T.; Okuno, S.; Ishiguro, K.; Sugawara, T. Sweet Potato Polyphenols. In Sweet Potato Chemistry, Processing and Nutrition; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 177–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Mu, T.; Sun, H. Profiling of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids in Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Leaves and Evaluation of Their Anti-Oxidant and Hypoglycemic Activities. Food Biosci. 2021, 39, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Mu, B.; Song, Z.; Ma, Z.; Mu, T. The In Vitro Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species of Sweet Potato Leaf Polyphenols. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 9017828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Nie, S.; Zhu, F. Chemical Constituents and Health Effects of Sweet Potato. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 90–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abong’, G.O.; Muzhingi, T.; Okoth, M.W.; Ng’ang’a, F.; Emelda Ochieng, P.; Mbogo, D.M.; Malavi, D.; Akhwale, M.; Ghimire, S. Processing Methods Affect Phytochemical Contents in Products Prepared from Orange-fleshed Sweetpotato Leaves and Roots. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donado-Pestana, C.M.; Salgado, J.M.; de Oliveira Rios, A.; dos Santos, P.R.; Jablonski, A. Stability of Carotenoids, Total Phenolics and In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity in the Thermal Processing of Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) Cultivars Grown in Brazil. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2012, 67, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; McFeeters, R.F.; Thompson, R.T.; Dean, L.L.; Shofran, B. Phenolic Acid Content and Composition in Leaves and Roots of Common Commercial Sweetpotato (Ipomea batatas L.) Cultivars in the United States. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, C343–C349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevallos-Casals, B.A.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. Stoichiometric and Kinetic Studies of Phenolic Antioxidants from Andean Purple Corn and Red-Fleshed Sweetpotato. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 3313–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Y.R.; Kim, I.; Lee, J. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.): Varietal Comparisons and Physical Distribution. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Oki, T.; Kai, Y.; Nishiba, Y.; Okuno, S. Effect of Repeated Harvesting on the Content of Caffeic Acid and Seven Species of Caffeoylquinic Acids in Sweet Potato Leaves. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 79, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletto, C.; Vianello, F.; Sambo, P. Effect of Different Home-Cooking Methods on Textural and Nutritional Properties of Sweet Potato Genotypes Grown in Temperate Climate Conditions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooko Abong’, G.; Muzhingi, T.; Wandayi Okoth, M.; Ng’ang’a, F.; Ochieng’, P.E.; Mahuga Mbogo, D.; Malavi, D.; Akhwale, M.; Ghimire, S. Phytochemicals in Leaves and Roots of Selected Kenyan Orange Fleshed Sweet Potato (OFSP) Varieties. Int. J. Food Sci. 2020, 3567972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majid, M.; Nasir, B.; Zahra, S.S.; Khan, M.R.; Mirza, B.; Haq, I.u. Ipomoeabatatas L. Lam. Ameliorates Acute and Chronic Inflammations by Suppressing Inflammatory Mediators, a Comprehensive Exploration Using In Vitro and In Vivo Models. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Yang, J.W.; Lee, J.S.; Oh, S.D.; Oh, S.; Lee, S.M.; Lim, M.H.; Park, S.K.; Jang, J.S.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Phytochemicals and Polar Metabolites from Colored Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Tubers. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, T.; Masuda, M.; Furuta, S.; Nishiba, Y.; Terahara, N.; Suda, I. Involvement of Anthocyanins and Other Phenolic Compounds in Radical-scavenging Activity of Purple-fleshed Sweet Potato Cultivars. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1752–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Lou, Q.; He, S. Antioxidant and Prebiotic Activity of Five Peonidin-Based Anthocyanins Extracted from Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steed, L.E.; Truong, V.D. Anthocyanin Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Selected Physical Properties of Flowable Purple-Fleshed Sweetpotato Purees. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, S215–S221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Cai, Y.Z.; Yang, X.; Ke, J.; Corke, H. Anthocyanins, Hydroxycinnamic Acid Derivatives, and Antioxidant Activity in Roots of Different Chinese Purple-Fleshed Sweetpotato Genotypes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 7588–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, V.R.; Renjith, R.S.; Mukherjee, A.; Anil, S.R.; Sreekumar, J.; Jyothi, A.N. Comparative Study on the Chemical Structure and in Vitro Antiproliferative Activity of Anthocyanins in Purple Root Tubers and Leaves of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2467–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montilla, E.C.; Hillebrand, S.; Butschbach, D.; Baldermann, S.; Watanabe, N.; Winterhalter, P. Preparative Isolation of Anthocyanins from Japanese Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Varieties by High-Speed Countercurrent Chromatography. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 9899–9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, J.B.; Cho, S.M.; Chung, M.N.; Lee, Y.M.; Chu, S.M.; Che, J.H.; Kim, S.N.; Kim, S.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; et al. Anthocyanin Changes in the Korean Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato, Shinzami, as Affected by Steaming and Baking. Food Chem. 2012, 130, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Su, X.; Lim, S.; Griffin, J.; Carey, E.; Katz, B.; Tomich, J.; Smith, J.S.; Wang, W. Characterisation and Stability of Anthocyanins in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato P40. Food Chem. 2015, 186, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Clifford, M.N. Profiling the Chlorogenic Acids of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) from China. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Saona, L.E.; Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Anthocyanin Pigment Composition of Red-Fleshed Potatoes. J. Food Sci. 1998, 63, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Ji, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Li, Y. Analysis on the Nutrition Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Different Types of Sweet Potato Cultivars. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Culley, D.; Yang, C.P.; Durst, R.; Wrolstad, R. Variation of Anthocyanin and Carotenoid Contents and Associated Antioxidant Values in Potato Breeding Lines. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2005, 130, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zeng, M.; Chen, J.; Jiao, Y.; Niu, F.; Tao, G.; Zhang, S.; Qin, F.; He, Z. Identification and Quantitation of Anthocyanins in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potatoes Cultivated in China by UPLC-PDA and UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Park, J.S.; Choi, D.S.; Jung, M.Y. Characterization and Quantitation of Anthocyanins in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potatoes Cultivated in Korea by HPLC-DAD and HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3148–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.D.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.D.; Qu, Z.Y.; Liu, M.; Zhu, S.H.; Liu, S.; Wang, M.; Qu, L. Identification and Thermal Stability of Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato Anthocyanins in Aqueous Solutions with Various PH Values and Fruit Juices. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossen, T.; Andersen, Ø.M. Anthocyanins from Tubers and Shoots of the Purple Potato, Solanum tuberosum. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2000, 75, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsufuji, H.; Kido, H.; Misawa, H.; Yaguchi, J.; Otsuki, T.; Chino, M.; Takeda, M.; Yamagata, K. Stability to Light, Heat, and Hydrogen Peroxide at Different PH Values and DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of Acylated Anthocyanins from Red Radish Extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3692–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.L.; Yu, Y.Q.; Chen, Z.J.; Wen, G.S.; Wei, F.G.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, C.; Xiao, X.L. Stability-Increasing Effects of Anthocyanin Glycosyl Acylation. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padda, M.S.; Picha, D.H. Quantification of Phenolic Acids and Antioxidant Activity in Sweetpotato Genotypes. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 119, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarpa, A.; González, M.C. Approach to the Content of Total Extractable Phenolic Compounds from Different Food Samples by Comparison of Chromatographic and Spectrophotometric Methods. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 427, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimala, B.; Nambisan, B.; Hariprakash, B. Retention of Carotenoids in Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato during Processing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Han, B.; Jiang, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhou, D.; Jia, X.; Li, X.; et al. Simultaneous Separation and Quantitation of Three Phytosterols from the Sweet Potato, and Determination of Their Anti-Breast Cancer Activity. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 174, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, N.; Freitas, N.; Faria, M.; Gouveia, M. Ipomoeabatatas (L.) Lam.: A Rich Source of Lipophilic Phytochemicals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12380–12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.N.; Nusrat, T.; Begum, P.; Ahsan, M. Carotenoids and β-Carotene in Orange Fleshed Sweet Potato: A Possible Solution to Vitamin A Deficiency. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.J.; Rickard, J.E.; Blanshard, J.M.V. Physicochemical Properties of Sweet Potato Starch. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1991, 57, 459–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, D.C.; Willcox, B.J.; Todoriki, H.; Suzuki, M. The Okinawan Diet: Health Implications of a Low-Calorie, Nutrient-Dense, Antioxidant-Rich Dietary Pattern Low in Glycemic Load. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2009, 28, 500S–516S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott, M.; Lim, C.C.; Ferguson, L.R. Dietary Protection against Free Radicals: A Case for Multiple Testing to Establish Structure-Activity Relationships for Antioxidant Potential of Anthocyanic Plant Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1081–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott, M.; Gould, K.S.; Lim, C.; Ferguson, L.R. In Situ and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Sweetpotato Anthocyanins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1511–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, M.; Takayanagi, T.; Harada, K.; Makino, K.; Ishikawa, F. Antioxidative Activity of Anthocyanins from Purple Sweet Potato, Ipomoera Batatas Cultivar Ayamurasaki. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Xie, B.; Ma, S.; Zhu, X.; Fan, G.; Pan, S. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activities of Principal Carotenoids Available in Water Spinach (Ipomoea aquatica). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, I.; Ishikawa, F.; Hatakeyama, M.; Miyawaki, M.; Kudo, T.; Hirano, K.; Ito, A.; Yamakawa, O.; Horiuchi, S. Intake of Purple Sweet Potato Beverage Affects on Serum Hepatic Biomarker Levels of Healthy Adult Men with Borderline Hepatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Gao, H.; Su, L.; Xie, J.; Chen, X.; Liang, H.; Wang, C.; Han, Y. Oral Hepatoprotective Ability Evaluation of Purple Sweet Potato Anthocyanins on Acute and Chronic Chemical Liver Injuries. Cell Biochem. Biophys 2014, 69, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, C.-L.; Deng, A.-P.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Zhang, J.-L. Characterization and Hepatoprotective Activity of Anthocyanins from Purple Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L. Cultivar Eshu No. 8). J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, B.; Tang, C.; Gou, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Liu, J.; Niu, F.; Kan, J. Characterization, Antioxidant Activity and Hepatoprotective Effect of Purple Sweetpotato Polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 115, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.-H.; Shimada, K.; Sekikawa, M.; Fukushima, M. Anthocyanin-Rich Red Potato Flakes Affect Serum Lipid Peroxidation and Hepatic SOD MRNA Level in Rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 1356–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Choi, C.Y.; Lee, K.J.; Hwang, Y.P.; Chung, Y.C.; Jeong, H.G. Hepatoprotective Effects of an Anthocyanin Fraction from Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato against Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Damage in Mice. J. Med. Food 2009, 12, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-F.; Fan, S.-H.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Lu, J.; Wu, D.-M.; Shan, Q.; Hu, B. Purple Sweet Potato Color Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response Induced by D-Galactose in Mouse Liver. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Shin, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, O. Shinzami Korean Purple-fleshed Sweet Potato Extract Prevents Ischaemia–Reperfusion-induced Liver Damage in Rats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2818–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Miyamae, Y.; Shigemori, H.; Isoda, H. Neuroprotective Effect of 3, 5-Di-O-Caffeoylquinic Acid on SH-SY5Y Cells and Senescence-Accelerated-Prone Mice 8 through the up-Regulation of Phosphoglycerate Kinase-1. Neuroscience 2010, 169, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Han, J.; Shimozono, H.; Villareal, M.O.; Isoda, H. Caffeoylquinic Acid-Rich Purple Sweet Potato Extract, with or without Anthocyanin, Imparts Neuroprotection and Contributes to the Improvement of Spatial Learning and Memory of SAMP8 Mouse. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 5037–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Shan, Q.; Ma, D. Purple Sweet Potato Color Repairs D-Galactose-Induced Spatial Learning and Memory Impairment by Regulating the Expression of Synaptic Proteins. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2008, 90, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.G.; Caruso, M.; Alcazar Magana, A.; Wright, K.M.; Maier, C.S.; Stevens, J.F.; Gray, N.E.; Quinn, J.F.; Soumyanath, A. Caffeoylquinic Acids in Centella Asiatica Reverse Cognitive Deficits in Male 5XFAD Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Suh, S.H.; Kim, C.R.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, C.-J.; Park, G.G.; Park, C.-S.; Shin, D.-H. Ligularia Fischeri Extract Protects against Oxidative-Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity in Mice and Pc12 Cells. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.-H.; Lee, H.-K.; Kim, J.-A.; Hong, S.-I.; Kim, H.-C.; Jo, T.-H.; Park, Y.-I.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, Y.-B.; Lee, S.-Y. Neuroprotective Effects of Chlorogenic Acid on Scopolamine-Induced Amnesia via Anti-Acetylcholinesterase and Anti-Oxidative Activities in Mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 649, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.J.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, H.K.; Harris, K.; Kim, C.-J.; Park, G.G.; Park, C.-S.; Shin, D.-H. 2, 4-Di-Tert-Butylphenol from Sweet Potato Protects against Oxidative Stress in PC12 Cells and in Mice. J. Med. Food 2013, 16, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnyana, I.M.O.; Sudewi, A.A.R.; Samatra, D.P.G.P.; Suprapta, D.N. Neuroprotective Effects of Purple Sweet Potato Balinese Cultivar in Wistar Rats with Ischemic Stroke. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnyana, I.M.O.; Sudewi, R.; Samatra, P.; Suprapta, S. Balinese Cultivar of Purple Sweet Potato Improved Neurological Score and BDNF and Reduced Caspase-Independent Apoptosis among Wistar Rats with Ischemic Stroke. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Lu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Hong, F.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, Y. Purple Sweet Potato Color Protects against High-Fat Diet-Induced Cognitive Deficits through AMPK-Mediated Autophagy in Mouse Hippocampus. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 65, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Mi, Y. Purple Sweet Potato Color Attenuates High Fat-Induced Neuroinflammation in Mouse Brain by Inhibiting MAPK and NF-ΚB Activation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 4823–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugata, M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Shih, Y.-C. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Activities of Taiwanese Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potatoes (Ipomoea batatas L. Lam) Extracts. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 768093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Nagane, M.; Aihara, N.; Kamiie, J.; Miyanabe, M.; Hiraki, S.; Luo, X.; Nakanishi, I.; Shoji, Y.; Matsumoto, K. Lipid-Soluble Polyphenols from Sweet Potato Exert Antitumor Activity and Enhance Chemosensitivity in Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 68, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Han, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, J.; Ma, W.; Zhou, D.; Li, X. Anti-Breast-Cancer Activity Exerted by β-Sitosterol-d-Glucoside from Sweet Potato via Upregulation of Microrna-10a and via the Pi3k–Akt Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 9704–9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, H.; Han, B.; Jiang, P.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Tian, C.; Zhou, D. Anti-Breast Cancer Activity of SPG-56 from Sweet Potato in MCF-7 Bearing Mice in Situ through Promoting Apoptosis and Inhibiting Metastasis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Ma, H.; He, K.; Zhou, D.; Li, Y.; Ye, X.; Li, X. A New Glycoprotein SPG-8700 Isolated from Sweet Potato with Potential Anti-Cancer Activity against Colon Cancer. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2322–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Chen, S.-J.; Chen, B.-W.; Zhang, K.-W.; Zhang, J.-J.; Xiao, R.; Li, P.-G. Gene Expression Profile of the Human Colorectal Carcinoma LoVo Cells Treated With Sporamin and Thapsigargin. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Xu, J.; Kim, J.; Chen, T.; Su, X.; Standard, J.; Carey, E.; Griffin, J.; Herndon, B.; Katz, B. Role of Anthocyanin-enriched Purple-fleshed Sweet Potato P40 in Colorectal Cancer Prevention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 1908–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-L.; Yu, H.-Y.; Zhang, X.-J.; Ke, M.; Hong, T. Purple Sweet Potato Anthocyanin Exerts Antitumor Effect in Bladder Cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundala, S.R.; Yang, C.; Lakshminarayana, N.; Asif, G.; Gupta, M.V.; Shamsi, S.; Aneja, R. Polar Biophenolics in Sweet Potato Greens Extract Synergize to Inhibit Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation and in Vivo Tumor Growth. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Koo, K.A.; Park, W.S.; Kang, D.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, B.Y.; Goo, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.K.; Woo, D.K. Anti-obesity Activity of Anthocyanin and Carotenoid Extracts from Color-fleshed Sweet Potatoes. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naomi, R.; Bahari, H.; Yazid, M.D.; Othman, F.; Zakaria, Z.A.; Hussain, M.K. Potential Effects of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) in Hyperglycemia and Dyslipidemia—A Systematic Review in Diabetic Retinopathy Context. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massi-Benedetti, M.; Federici, M.O. Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Type 2 Diabetes: The Role of Hyperglycaemia. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 1999, 107, S120–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, D.; Brillon, D.; Colombo, P.C.; Schmidt, A.M. Human Vascular Endothelial Cells: A Model System for Studying Vascular Inflammation in Diabetes and Atherosclerosis. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2011, 11, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loke, W.M.; Proudfoot, J.M.; Hodgson, J.M.; McKinley, A.J.; Hime, N.; Magat, M.; Stocker, R.; Croft, K.D. Specific Dietary Polyphenols Attenuate Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E–Knockout Mice by Alleviating Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Fan, S.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Shan, Q.; Zheng, Y. Purple Sweet Potato Color Inhibits Endothelial Premature Senescence by Blocking the NLRP3 Inflammasome. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selokela, L.M.; Laurie, S.M.; Sivakumar, D. Impact of Different Postharvest Thermal Processes on Changes in Antioxidant Constituents, Activity and Nutritional Compounds in Sweet Potato with Varying Flesh Colour. South Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 144, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Domínguez-López, I.; López-Yerena, A.; Vallverdú Queralt, A. Current Strategies to Guarantee the Authenticity of Coffee. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, M.; Lopez-Yerena, A.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A. Traceability, Authenticity and Sustainability of Cocoa and Chocolate Products: A Challenge for the Chocolate Industry. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, M.; Ye, Y.; Yu, D. Influence of Ultrasonic Pretreatments on Drying Kinetics and Quality Attributes of Sweet Potato Slices in Infrared Freeze Drying (IRFD). LWT 2020, 131, 109801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, J.A.; Norton, T.; Alagusundaram, K.; Tiwari, B.K. Novel Drying Techniques for the Food Industry. Food Eng. Rev. 2014, 6, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, J.F.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Mao, L.C. Effects of Drying Processes on the Antioxidant Properties in Sweet Potatoes. Agric. Sci. China 2010, 9, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savas, E. The Modelling of Convective Drying Variables’ Effects on the Functional Properties of Sliced Sweet Potatoes. Foods 2022, 11, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, J.A.; Truong, V.-D.; Daubert, C.R. Nutritional and Rheological Characterization of Spray Dried Sweetpotato Powder. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Singh, S.V. Spray Drying of Fruit and Vegetable Juices—A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, S.; Cueva-Mestanza, R.; de Pascual-Teresa, S. Effect of Spray Drying on the Polyphenolic Compounds Present in Purple Sweet Potato Roots: Identification of New Cinnamoylquinic Acids. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Li, J.; Guan, Y.; Zhao, G. Effect of Carriers on Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activities and Biological Components of Spray-Dried Purple Sweet Potato Flours. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagnika, C.; Riaz, A.; Jiang, N.; Song, J.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, M. Effects of Pretreatment and Drying Methods on the Quality and Stability of Dried Sweet Potato Slices during Storage. J. Food Processing Preserv. 2021, 45, e15807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalos, R.A.; Naef, E.F.; Aviles, M.V.; Gómez, M.B. Vacuum Impregnation: A Methodology for the Preparation of a Ready-to-Eat Sweet Potato Enriched in Polyphenols. LWT 2020, 131, 109773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kręcisz, M.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Stępień, B.; Łyczko, J.; Pasławska, M.; Musiałowska, J. Influence of Drying Methods and Vacuum Impregnation on Selected Quality Factors of Dried Sweet Potato. Agriculture 2021, 11, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; López-Yerena, A.; Lozano-Castellón, J.; Olmo-Cunillera, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Martin-Belloso, O.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A. Impact of Emerging Technologies on Virgin Olive Oil Processing, Consumer Acceptance, and the Valorization of Olive Mill Wastes. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Zhu, F. Effect of Ultrasound on Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Sweetpotato and Wheat Flours. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 66, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, M.; Sit, N. Application of Ultrasound in Combination with Other Technologies in Food Processing: A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 73, 105506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, R.A.; Azoubel, P.M.; de Lima, M.A.B.; Stamford, T.C.M.; Araújo, A.S.; de Mendonça, W.S.; da Silva Vasconcelos, M.A. Ultrasound Pretreatment Application in Dehydration: Its Influence on the Microstructure, Antioxidant Activity and Carotenoid Retention of Biofortified Beauregard Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 4542–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.T.; Ma, H.; Jatoi, M.A.; Hashim, M.M.; Wali, A.; Safdar, B. Influence of Ultrasonic Pretreatment with Hot Air Drying on Nutritional Quality and Structural Related Changes in Dried Sweet Potatoes. Int. J. Food Eng. 2019, 15, 20180409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derossi, A.; Husain, A.; Caporizzi, R.; Severini, C. Manufacturing Personalized Food for People Uniqueness. An Overview from Traditional to Emerging Technologies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1141–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betoret, E.; Betoret, N.; Rocculi, P.; Dalla Rosa, M. Strategies to Improve Food Functionality: Structure–Property Relationships on High Pressures Homogenization, Vacuum Impregnation and Drying Technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murador, D.C.; da Cunha, D.T.; de Rosso, V.V. Effects of Cooking Techniques on Vegetable Pigments: A Meta-Analytic Approach to Carotenoid and Anthocyanin Levels. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakrawati, D.; Srivichai, S.; Hongsprabhas, P. Effect of Steam-Cooking on (Poly) Phenolic Compounds in Purple Yam and Purple Sweet Potato Tubers. Food Res. 2021, 5, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, C.; Zelaya-Medina, C.F.; Chinchilla, N.; Ferreiro-González, M.; Barbero, G.F.; Palma, M. How Different Cooking Methods Affect the Phenolic Composition of Sweet Potato for Human Consumption (Ipomea batata (L.) Lam). Agronomy 2021, 11, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.H.; Koh, E. Effects of Cooking Methods on Anthocyanins and Total Phenolics in Purple-fleshed Sweet Potato. J. Food Processing Preserv. 2016, 40, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Mu, T.; Ma, M.; Blecker, C. Optimization of Processing Technology Using Response Surface Methodology and Physicochemical Properties of Roasted Sweet Potato. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musilova, J.; Lidikova, J.; Vollmannova, A.; Frankova, H.; Urminska, D.; Bojnanska, T.; Toth, T. Influence of Heat Treatments on the Content of Bioactive Substances and Antioxidant Properties of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Tubers. J. Food 2020, 2020, 8856260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franková, H.; Musilová, J.; Árvay, J.; Šnirc, M.; Jančo, I.; Lidiková, J.; Vollmannová, A. Changes in Antioxidant Properties and Phenolics in Sweet Potatoes (Ipomoea batatas L.) Due to Heat Treatments. Molecules 2022, 27, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, G.; Amoros, W.; Muñoa, L.; Sosa, P.; Cayhualla, E.; Sanchez, C.; Díaz, C.; Bonierbale, M. Total Phenolic, Total Anthocyanin and Phenolic Acid Concentrations and Antioxidant Activity of Purple-Fleshed Potatoes as Affected by Boiling. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 30, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, G.; Ye, F. Destabilisation and Stabilisation of Anthocyanins in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potatoes: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Origin | Sample Extraction | Analytical Method | Phytochemical | Amount of Phytochemical | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | Methanol (80%) | Folin-Ciocalteu | TPC | ~0.2 to 0.7 mg CA/g FW | [9] |

| pH-differential | TCA | ~0.1 to 0.4 mg TCA/g FW | |||

| Korea | 0.2% HCl in methanol | UHPLC-(ESI)-Qtof, UPLC-Ion trap, and HPLC -DAD | Peo-3-O-glc | 6544 to 26,483 mg/kg DW | [22] |

| Cya -3-O-glc | 943 to 3962 mg/kg DW | ||||

| Pg-3-O-glc | 1242 to 2181 mg/kg DW | ||||

| 0.2% HCl in methanol | UHPLC-(ESI)-QqQ | Phenolic acids: caffeic acid, ferulic acid, chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, cis-ferulic acid, trans-ferulic acid, caffeoylquinic acid, and dicaffeoylquinic acids. | Phenolic acids (mg/Kg DW): Caffeic acid: 44 to 70, cis-ferulic acid; 2 to 7, trans-ferulic acid: 1 to 7, chlorogenic acid: 6714 to 13268, p-coumaric acid: 1, caffeoylquinic acid: 5150 to 5862, dicaffeoylquinic acids 19 to 24. | [22] | |

| Flavonoids: quercetin 3-O-galactoside, and quercetin-3-O-glc, quercetin diglc. | Flavonoids (mg/kg DW): Quercetin 3-O-galactoside:1, quercetin-3-O-glc: 1 to 7, quercetin diglc: 6 to 30. | ||||

| 0.2% HCl in methanol | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | 1.80 to 7.37 mg GA/100 g DW | [22] | |

| Japan | Ethanol (80%) | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | 0.2 to 1.2 µmol CA/mL. | [28] |

| Reverse-phase HPLC | Peo and Cya | NS | |||

| China | Water, 3.5% citric acid, and 79 U/mL cellulose | HPLC- MS/MS | Cya-based anthocyanins and peo-based anthocyanins | 13.7 mg total anthocyanins /100 g | [29] |

| USA | 7% acetic acid in methanol (80%) | Folin–Ciocalteu | TPC | 408.1 mg CA/100 g FW (raw) | [30] |

| 401.6 mg CA/100 g FW (puree) | |||||

| 7% acetic acid in methanol (80%) | pH-differential | Total monomeric anthocyanin | 101.5 mg cya-3-glc/100 g FW (raw) 80.2 mg cya-3-glc/100 g FW (puree) | [30] | |

| China | Methanol (85%) with 0.5% formic acid | LC−PDA−APCI−MS | Total monomeric anthocyanins: cya 3-soph-5-glc, cya 3-(6′′-p-caffeoylsoph)-5-glc, peo 3-soph-5-glc, cya 3-(6′′-p-feruloylsoph)-5-glc, peo 3-(6′′-p-feruloylsoph)-5-glc | 305.0 mg anthocyanins/100 g DW | [31] |

| Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives: caffeoyl-hexoside, 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid, caffeic acid, feruloylquinic acid, 3,4-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid | 854.4 mg hydroxycinnamic acids/100 g DW | ||||

| Korea | Methanol (50%) with 1.2 M HCl at 80 °C | HPLC system | Flavonoids: quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol, luteolin. | Flavonoids: 579.5 µg/g DW (Quercetin: 388.9, myricetin: 152, kaempferol: 23.4, luteolin: 15.2) | [27] |

| Anthocyanins: Cya, Peo. | Anthocyanins: 727.4 µg/g DW (Cya: 408.4, and Peo: 319.1) | ||||

| Phenolic acids: ferulic, p-coumaric, p-hydroxybenzoic, sinapic, syringic, and vanillic acids. | Phenolic acids: 744.3 µg/g DW (p-hydroxybenzoic acid: 238.6, vanillic acid: 147.4, syringic acid: 3.9, p-coumaric: 18.1, ferulic acid: 322.3, sinapic acid: 14.1) | ||||

| India | Different extraction solvents: methanol/trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (99.5:0.5), ethanol/TFA (99.5:0.5), methanol/TFA/water (80:19.5:0.5), and ethanol/TFA/water (80:19.5:0.5) | HR-ESI–MS | TAC | 43.4 mg peonidin-3-O-glc equivalent /100 g of FW | [32] |

| Japan | Methanol/acetic acid (19:1, v/v), methanol/water (1:1, v/v), and tert-butyl methyl ether/methanol (7:2, v/v) | HPLC-DAD, HPLC-ESI-MSn | Cya 3-soph-5-glc (Cya-3-(6′′-caffeoylsoph)-5-glc, cya-3-(6′′-caffeoylsoph)-5-glc, cya-3-(6′′-caffeoyl-6′′′-feruloylsoph)-5-glc, cya-3-feruloylsoph-5-glc) | NS | [33] |

| Peo3-soph-5-glc (Peo-3-(6′′-caffeoylsoph)-5-glc, peo-3-feruloylsoph-5-glc, peo-3-(6′′,6′′′-dicaffeoylsoph)-5-glc, peo-3-(6′′-caffeoyl-6′′′-feruloylsoph)-5-glc, peo-3-(6′′-caffeoyl-6′′′-p-hydroxybenzoylsoph)-5-glc, peo-3-p-hydroxybenzoylsoph-5-glc) | |||||

| China | Ethanol with 1% formic acid | UPLC-PDA, UPLC-QTOF-MS, UPLC-MS/MS analyses | TAC | 90.5 to 1018 mg/100 g DW | [31] |

| Monoacylated anthocyanin | 0.0 to 44.8 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Diacylated anthocyanin | 79.9 to 982.9 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Acylated-based anthocyanin | 90.5 to 1018.7 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Cya-based anthocyanin | 25.7 to 326.6 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Peo-based anthocyanin | 0.0 to 761.7 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Korea | Methanol with 0.2% HCl | HPLC-TOF/MS, HPLC/MS/MS, and UV/vis spectroscopy | TAC | 383.2 to 1190.2 mg/100 gDW | [22] |

| Non-acylated anthocyanin | 17.5 to 35.8 mg/100 gDW | ||||

| Monoacylated anthocyanin | 158.2 to 323.4 mg/100 gDW | ||||

| Diacylated-based anthocyanin | 199.6 to 845.1 mg/100 gDW | ||||

| Cya-based anthocyanin | 98.2 to 815.1 mg/100 gDW | ||||

| Peo-based anthocyanin | 281.5 to 740.8 mg/100 gDW | ||||

| Pg-based anthocyanin | 1.2 to 217.0 mg/100 gDW | ||||

| Korea | 5% formic acid in water | LC-DAD-ESI/MS | TAC | Raw: 1342 mg/100 g DW | [34] |

| Steamed 751 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Roasted 1086 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| USA | 5% formic acid water | HPLC/MS-MS | TAC | Raw: 1390 mg/100 g DW | [35] |

| Baked: 1303 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Steamed: 1284 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Microwaved: 1275 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Pressured cook: 1165 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Fried: 1217 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Total Cya content (Cya 3-p-hydroxybenzoyl soph -5-glc, cya 3-(6″-caffeoyl soph)-5-glc, cya 3-(6″ -feruloyl soph)-5-glc, cya 3-(6″,6″′-dicaffeoyl soph)-5-glc, cya 3-caffeoyl-p-hydroxybenzoyl soph -5-glc, cya 3-(6″-caffeoyl-6″′-feruloyl soph)-5-glc) | Raw: 930 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Baked: 943 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Steamed: 1060 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Microwaved: 1038 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Pressured cook: 943 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Fried: 937 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Total peo content (Peo 3-p-hydroxybenzoyl soph-5-glc, peo 3-(6″-feruloyl soph)-5-glc, peo 3-caffeoyl soph -5-glc, peo 3-caffeoyl-p-hydroxybenzoyl soph -5-glc, peo 3-(6″-caffeoyl-6″′-feruloyl soph)-5-glc) | Raw: 460 mg/100 g DW | ||||

| Baked: 360 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Steamed: 224 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Microwaved: 237 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Pressured cook: 222 mg/100 g DW | |||||

| Fried: 280 mg /100 g DW | |||||

| China | Methanol:Water (7:3, v/v) | HPLC-MS | 5-caffeoylquinic acid, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid | NS | [36] |

| Sweet Potato Flesh Color (Origin) | Sample Extraction | Analytical Method | Phytochemical | Amount of Phytochemical | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (USA) | Methanol (80%) | Folin-Ciocalteu | TPC | <0.1 mg CA/g FW | [9] |

| White and orange (Italy) | Methanol | Folin-Ciocalteu | TPC | Raw: 794 mg GA/kg DW | [24] |

| Boiled: 1803 mg GA/kg DW | |||||

| Fried: 2605 mg GA/kg DW | |||||

| Microwaved: 1836 mg GA/kg DW | |||||

| Steamed: 1743 mg GA/kg DW | |||||

| White-fleshed (Korea) | 50% MeOH withn1.2 M HCl at 80 °C | HPLC system | Flavonoids: quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol. | Flavonoids: 45.4 µg/g DW (Quercetin: 19.8, myricetin: 23.4, kaempferol: 2.1) | [27] |

| Phenolic acids: ferulic, p-coumaric, p-hydroxybenzoic, sinapic, syringic, and vanillic acids. | Phenolic acids: 52.5 µg/g DW (p-hydroxybenzoic acid: 5.5, vanillic acid: 7.5, syringic acid: 3.7, p-coumaric: 7.5, ferulic acid: 15.1, sinapic acid: 13.3) | ||||

| Yellow (USA) | Methanol (80%) | Folin-Ciocalteu | TPC | <0.1 mg CA/g FW | [9] |

| Red (Peru) | Methanol | Folin-Ciocalteu | TPC | 945 mg CA/100 g FW 3220 mg CA/100 g DW | [21] |

| 0.225 N HCl in ethanol (95%) | pH-differential | Total monomeric anthocyanins (Cya 3-glc) | 182 mg total anthocyanins/g FW 618 mg total anthocyanins/g DW | ||

| Red | NS | pH-differential | TAC | 2.4 to 40.3 mg total anthocyanins/g FW | [37] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laveriano-Santos, E.P.; López-Yerena, A.; Jaime-Rodríguez, C.; González-Coria, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Romanyà, J.; Pérez, M. Sweet Potato Is Not Simply an Abundant Food Crop: A Comprehensive Review of Its Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and the Effects of Processing. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091648

Laveriano-Santos EP, López-Yerena A, Jaime-Rodríguez C, González-Coria J, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Vallverdú-Queralt A, Romanyà J, Pérez M. Sweet Potato Is Not Simply an Abundant Food Crop: A Comprehensive Review of Its Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and the Effects of Processing. Antioxidants. 2022; 11(9):1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091648

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaveriano-Santos, Emily P., Anallely López-Yerena, Carolina Jaime-Rodríguez, Johana González-Coria, Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, Anna Vallverdú-Queralt, Joan Romanyà, and Maria Pérez. 2022. "Sweet Potato Is Not Simply an Abundant Food Crop: A Comprehensive Review of Its Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and the Effects of Processing" Antioxidants 11, no. 9: 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091648

APA StyleLaveriano-Santos, E. P., López-Yerena, A., Jaime-Rodríguez, C., González-Coria, J., Lamuela-Raventós, R. M., Vallverdú-Queralt, A., Romanyà, J., & Pérez, M. (2022). Sweet Potato Is Not Simply an Abundant Food Crop: A Comprehensive Review of Its Phytochemical Constituents, Biological Activities, and the Effects of Processing. Antioxidants, 11(9), 1648. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11091648