Abstract

Bioactive compounds in berries may scavenge reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by donating electrons to free radicals, thereby protecting DNA, proteins, and lipids from oxidative damage. Evidence shows that berry consumption has beneficial health effects, though it remains unclear whether berries exert a significant impact on oxidative stress in humans. Thus, we performed a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) to examine the effects of non-acute (more than a single dose and ≥7 days) berry consumption on biomarkers of oxidative stress. Searches were conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Scopus; results were imported into Covidence for screening and data extraction. The literature search identified 622 studies that were screened, and 131 full-text studies assessed for eligibility. Ultimately, 28 RCTs met the eligibility criteria. Common biomarkers of oxidative stress (antioxidants, DNA damage, isoprostanes, malondialdehyde, and oxidized LDL) were systematically reviewed, and results were reported narratively. Of the approximate 56 oxidative stress biomarkers evaluated in the 28 RCTs, 32% of the biomarkers were reported to have statistically significant beneficial results and 68% of the biomarkers were reported as having no statistically significant differences. More well-designed and longer-term berry RCTs are needed to evaluate biomarkers of oxidative stress.

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress is implicated in the pathogenesis of age-related decline in diseases like Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular disease, and various cancers [1,2,3,4]. Interventions that emphasize healthful plant-based, polyphenol-rich diets are promoted for preventing and managing diseases related to oxidative stress [5,6,7]. Plant polyphenols are a varied grouping of complex structures. Polyphenols are phenolic compounds classified as flavonoids or non-flavonoids. Flavonoids are comprised of anthocyanins, flavan-3-ols, flavanones, flavones, flavonols and isoflavones. Non-flavonoids are stilbenoids, lignins and phenolic acids [8]. Berries are among the most potent sources of bioactive compounds such as vitamin C, carotenoids, and polyphenols, including anthocyanins [9,10]. Anthocyanins are polyphenolic pigments that are responsible for the red, blue, and purple colors present in berries [11]. Further, there are six common anthocyanins, which include cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and petunidin. Anthocyanins may consist of up to 60% of the total phenolic compounds in berries. However, the quantity and structure of anthocyanins vary greatly in plant foods due to agriculture and processing [9,12]. Increasing research interest has focused on the health benefits of anthocyanins and/or anthocyanin-rich foods, such as berries [13]. Currently, food-based guidelines for anthocyanin intake are not currently available in North America, South America, or Europe. However, China has previously defined a proposed level of 50 mg per day for anthocyanins [14]. Current public health recommendations to increase dietary intake of fruits including berries are determined by the need for sufficient nutrient intake from foods, though some dietary guidelines also consider the contribution of dietary bioactive compounds such as anthocyanins [15]. Global consumption of anthocyanins is dependent upon the region of the world; the mean intake of anthocyanins ranges from 15 mg per day to 50 mg per day [16]. Finland’s adult population has a higher dietary intake of berries, with a mean intake of anthocyanins of approximately 50 mg per day [17]. The adult population of the United States has a lower intake of berries, consuming about 15 mg per day of anthocyanins [18].

The bioactive compounds in berries scavenge reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by donating electrons to free radicals, thereby protecting DNA, proteins, and lipids from oxidative damage [19,20,21]. A number of systematic and narrative reviews have described the benefits of specific types of berries and polyphenols on health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders and cancer [10,13,22,23,24]. It remains unclear whether berries and their extracts, collectively, exert a significant impact on biomarkers of oxidative stress in humans. A body of evidence to support the effects of berries on oxidative stress in humans would inform our understanding of the mechanisms linking berry consumption and health outcomes. The objective of this research was to conduct a systematic review to examine the effects of berry consumption on biomarkers of oxidative stress in adults from randomized controlled trials (RCT) involving non-acute (more than a single dose and ≥7 days) berry/berry extract feeding in the last 10 years.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was registered on 1 February 2023 in the PROSPERO registry (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=393595, accessed on 1 February 2023). Additionally, the review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [25]. The search was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses literature search extension (PRISMA-S) guidelines [26]. Peer review of the search strategies was not completed.

2.1. Information Sources

The searches were conducted and exported on 24 February 2023 in the following electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library (via Cochranelibrary.org), and Scopus (Elsevier). Grey literature sources included a clinical trial registry (ClinicalTrials.gov).

2.2. Search Strategy

An initial list of search terms was developed by a health sciences librarian in collaboration with all authors. The three concepts explored in this review include (1) berries; (2) oxidative stress; and (3) anthocyanins. The berries concept was developed by brainstorming a list of common berries, and was then expanded through a review of biological species. The authors achieved consensus on including blackcurrant as a berry after some debate. Fruit was also included as a search term since PubMed does not have a subject heading for the term berry. Many relevant indexed articles included fruit as a MeSH term, so it was recommended to include that term in the search strategy. Search terms for the oxidative stress concept were developed through discussion of oxidative stress biomarkers. The anthocyanins concept was developed through discussion and controlled vocabulary exploration. The search strategy was finalized in PubMed and then translated to Cochrane Library and Scopus. The reproducible searches for all databases are available at https://doi.org/10.11571/upei-roblib-data/researchdata:790 (accessed on 23 May 2023). The search identified RCTs published from 1 January 2013 to 24 February 2023.

Search Filters

The publication type was limited to RCTs, using a modified version of Cochrane’s sensitivity and precision-maximizing filter for PubMed [27]. The search was limited to human studies by using a common search filter for excluding publications that include animals or animals and humans through the use of the NOT Boolean operator. An English language filter and a date range of 2013 to 2023 were also applied.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review included only RCTs examining the effect of chronic berry consumption on oxidative stress biomarkers. Eligible interventions were dietary sources of berries, including foods, extracts, and supplements. Eligible trial populations included participants of all ages, ethnicities, sexes, and health–disease statuses. Trials that evaluated the impact of acute berry consumption (with a single dose) were not considered. Animal studies, in vitro studies, and observational studies were also excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction

Literature search results were imported into Covidence, an online systematic review software for deduplication, screening, and data extraction. Abstract and title screening was completed by one reviewer. Full-text review, data extraction, and bias assessment were completed independently by two blinded reviewers. Extraction was completed using Covidence’s Extraction 2 tool, which was fully customizable to the needs of the project. Conflicts were resolved by review and discussion with all review authors.

For each included RCT, the risk of bias was judged as high, low, or unclear using Covidence’s Risk of Bias assessment version 1.0. This tool includes the Cochrane Risk of Bias domains of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and ‘other issues’ [28]. An overall risk-of-bias judgment (either high risk of bias, low risk of bias, or some concerns) was assigned to each study. Stata SE software (version 16.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all calculations.

3. Results

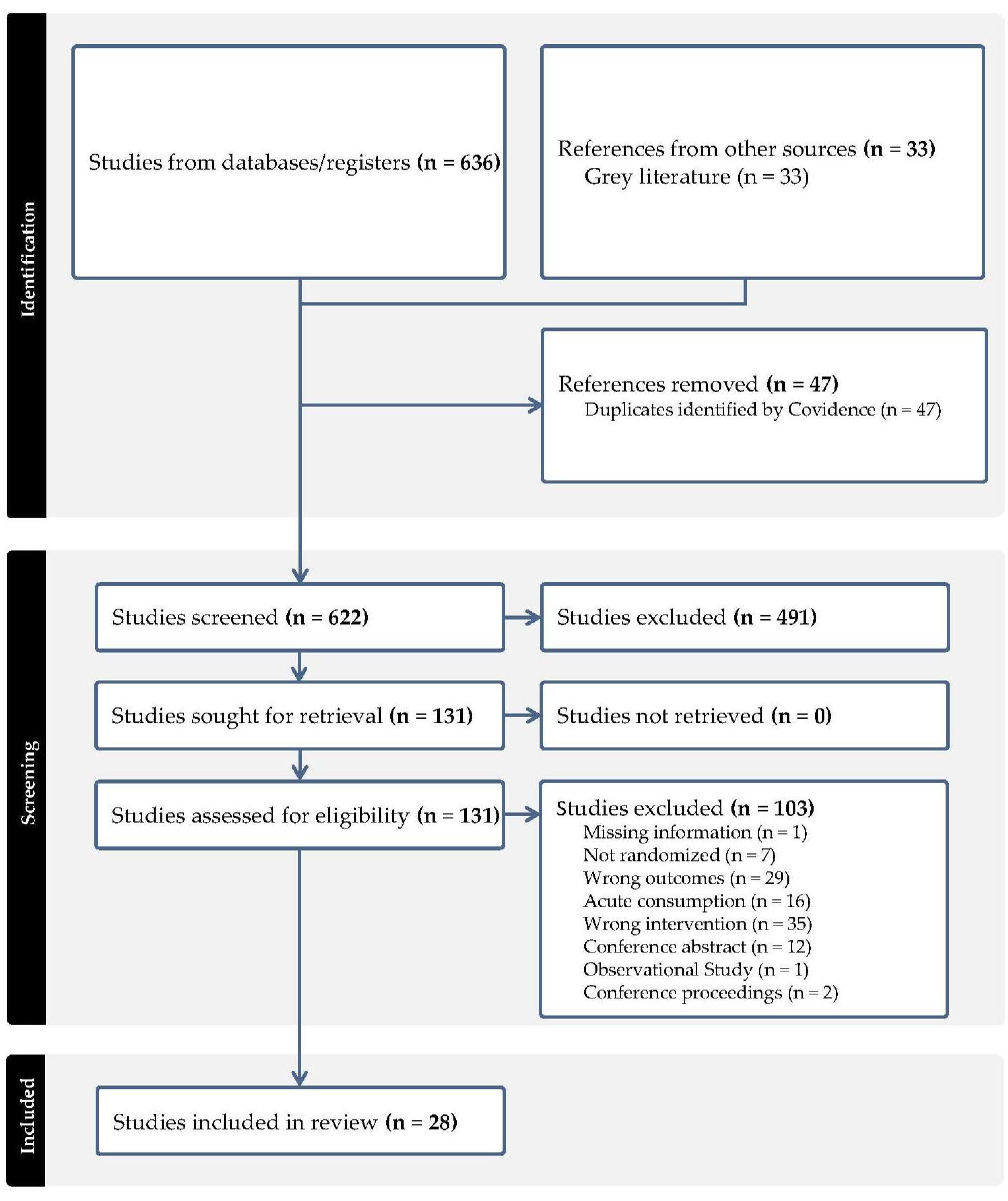

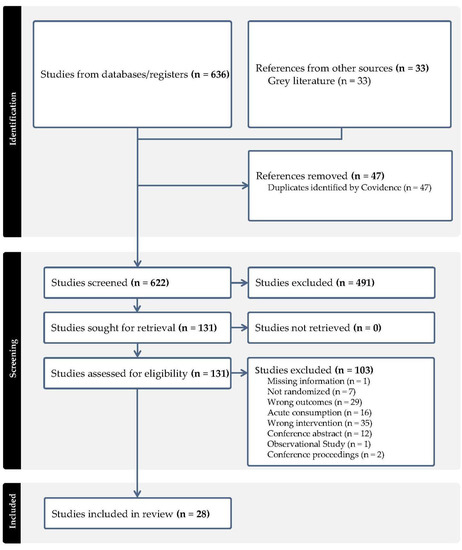

The literature search identified 636 studies that were imported from screening. Out of these, 47 study duplicates were removed and 622 studies were screened, with 491 studies determined to be irrelevant. Ultimately, 131 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility, with 103 out of the 131 studies excluded primarily due to the wrong intervention unrelated to berries. A total of 28 RCTs met the eligibility criteria [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1 (PRISMA).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of literature search and study selection.

3.1. Study and Subject Characteristics

A summary of the characteristics of the included RCTs is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics and most common biomarkers of oxidative stress reported by the 28 randomized controlled trials 1.

Individual study characteristics are shown in Table 2. The 28 studies included in the systematic review were all RCTs. The study designs used were 19 (68%) parallel RCTs [29,30,31,32,34,35,36,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,48,50,51,56] and 9 (32%) crossover RCTs [33,37,39,46,49,52,53,54,55]. Of the RCTs, 64% were double-blinded. Study sample sizes ranged from 10 to 138 subjects; the sample sizes in 43% of these RCTs ranged from 31 to 50 subjects. The intervention duration of the RCTs ranged from 7 days to 24 weeks. Some 71% of RCTs had an intervention duration of >4 weeks to 12 weeks.

Table 2.

Study and subject characteristics with results for biomarkers of oxidative stress reported by the 28 randomized controlled trials.

Subjects ranged in age from 18 years to 74 years, and 57% of these subjects had a mean age of <50 years. Three out of 28 RCTs did not include females as subjects. fivesome 25 of the 28 RCTs did not report the subjects’ race. The majority (64%) of the study populations were those at risk for diseases such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Several studies included subjects with active disease states such as bladder cancer [48], liver disease [38] and type 2 diabetes [33]. In addition, 46% of the subjects were considered overweight, 29% were considered obese, and 25% were normal weight.

For the berry interventions, six RCTs reported using blueberries [32,35,43,47,52,54]; three RCTs each reported using acai [37,45,55], aronia (chokeberry) [51,53,56], blackcurrant [41,42,44], and cranberry [34,40,48]; and two RCTs each reported using agraz [39,46], bilberry [29,33], and mixed berries [49,50]. There was only one RCT each using maqui berry [36], pomegranate [38], strawberry [31], and whortleberry [30]. RCTs reported using differing formulations of berries. Ten (36%) RCTs used freeze-dried berry powders [29,31,35,39,40,43,46,47,52,53], ten (36%) used berry extracts [30,32,33,34,36,41,42,48,50,56], seven (25%) used berry juice [37,38,44,45,49,51,54], and one (3%) used berry pulp [55]. Regarding the differing formulations, 71% of RCTs using juice, 60% of RCTs using freeze-dried berries, and 30% of RCTs using berry extracts reported a statistically significant effect on selected biomarkers of oxidative stress, respectively. Most RCTs (79%) reported the anthocyanin content of the berry interventions, which ranged from 6.22 mg to 2250 mg (Table 2).

3.2. Oxidative Stress Markers Assessed

Collectively, the included RCTs reported on >10 separate biomarkers of oxidative stress. More than 68% (n = 19) of the RCTs reported results for blood antioxidants such as ferric-reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP), glutathione, oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC), superoxide dismutase (SOD), total antioxidant capacity (TAC), and thiols [29,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,41,42,43,46,47,48,50,52,53,55,56]. Other commonly reported biomarkers were isoprostanes (n = 9) [34,36,39,40,44,45,53,54,56], malondialdehyde (n = 7) [30,31,32,38,41,49,55], and oxidized LDL (n = 7) [29,34,36,49,50,54,56]. Several RCTs reported on biomarkers for DNA damage such as % DNA in tail (n = 3) [33,52,55] and urine 8-oxoguanine (8-OHdG) (n = 3) [33,34,39]. Few RCTs reported using lipid peroxidation biomarkers such as thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) (n = 2) [39,51], protein oxidation using myeloperoxidase (n = 1) [46], and reactive oxygen species (n = 1) [41].

3.3. Risk of Bias

The Cochrane Risk-of-Bias assessment graded the strength of the body of evidence, which included RCTs with a parallel design (n = 19) or crossover design (n = 9). Of the 28 RCTs, 8 (29%) studies showed a low risk of bias, 17 (61%) showed some concerns for risk of bias, and 3 (10%) RCTs showed a high risk of bias. These results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cochrane assessment of risk of bias.

Of the 19 RCTs with a parallel design, only 2 (10%) warranted an overall high risk-of-bias judgement due to the blinding of participants, personnel, or outcome assessment, along with missing outcome data. Of the remaining studies with a parallel design, 10 (53%) RCTs had some concerns regarding risk of bias, due to several of the domains including sequence generation, allocation concealment, the blinding of participants, personnel, or the outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data. Lastly, 7 (37%) parallel-design RCTs showed a low risk of bias.

One (11%) out of nine crossover-design RCTs showed a high risk of bias due to the blinding of participants and or personnel, along with the blinding of the outcome assessment. The majority of the crossover-design RCTs, i.e., 7 (78%), had some concerns regarding risk of bias due to sequence generation, allocation concealment, the blinding of participants, personnel, or the outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data. One (11%) crossover design RCT showed a low risk of bias.

3.4. Synthesis of Results

Table 2 presents results from all included studies for changes in oxidative stress biomarkers related to berry consumption in RCTs. When berry interventions were compared with control groups, RCTs reported either statistically significant beneficial effects or no statistically significant differences in oxidative stress biomarkers. The results of biomarkers reported by three or more studies (antioxidants, DNA damage, isoprostanes, malondialdehyde and oxidized LDL) are reported below.

3.4.1. Antioxidants

In 19 RCTs evaluating antioxidant biomarkers, 6 (32%) studies using interventions with acai juice, acai pulp, agraz freeze-dried powder, aronia (chokeberry) freeze-dried powder, cranberry extract, and pomegranate juice reported statistically significant increases in antioxidant capacity. Thirteen (68%) RCTs using interventions with agraz freeze-dried powder, aronia (chokeberry) extract, bilberry freeze-dried powder, bilberry extract, blackcurrant extract, blackcurrant juice, blueberry freeze-dried powder, blueberry extract, cranberry extract and a mixed berry extract of cranberry/strawberry reported no differences in antioxidant biomarkers.

3.4.2. DNA Damage

In three RCTs evaluating % DNA in tail from comet assays, one (33%) study using blueberry freeze-dried powder reported statistically significant beneficial results. Two (67%) studies using acai pulp and bilberry extract reported no statistically significant differences.

In three RCTs reporting urinary 8-OHdG, one (33%) study using agraz freeze-dried powder reported statistically significant beneficial results. Two (67%) studies using bilberry extract and cranberry extract reported no statistically significant differences.

3.4.3. Isoprostanes

Of nine RCTs evaluating isoprostanes, four (44%) studies using acai juice, blackcurrant juice, cranberry freeze-dried powder, and maqui berry extract reported statistically significant beneficial results. Five (56%) studies using agraz freeze-dried powder, aronia berry freeze-dried powder, aronia berry extract, blueberry juice, and cranberry extract reported no statistically significant differences.

3.4.4. Malondialdehyde

In seven RCTs evaluating malondialdehyde, three (43%) studies using acai pulp, strawberry freeze-dried powder, and whortleberry extract reported statistically significant beneficial results. Four (57%) studies using blueberry extract, blackcurrant extract, a mixed berry (blueberries, blackcurrant, elderberry, lingonberries and strawberry) juice, and pomegranate juice reported no statistically significant differences.

3.4.5. Oxidized LDL

In seven RCTs evaluating oxidized LDL, two (29%) studies using bilberry freeze-dried powder and maqui berry extract reported statistically significant beneficial results. Five (71%) studies using aronia berry extract, blueberry juice, cranberry extract, cranberry/strawberry extract, and a mixed berry (blueberries, blackcurrant, elderberry, lingonberries and strawberry) juice reported no statistically significant differences.

Collectively, of the 56 oxidative stress biomarkers reported by the 28 RCTs, 18 (32%) oxidative stress biomarkers were reported to have statistically significant beneficial results, and 38 (68%) oxidative stress biomarkers were reported to have no statistically significant differences.

4. Discussion

In this study, we conducted a systematic review to determine gaps in the literature and summarize the available evidence on the effect of ≥7 days of berry consumption on biomarkers of oxidative stress in adults over the last 10 years. The 28 RCTs identified in this systematic review reported >10 different biomarkers of oxidative stress. Biomarkers reported by three or more RCTs, including antioxidants, DNA damage, isoprostanes, malondialdehyde and oxidized LDL, were systematically reviewed.

The reviewed literature revealed several gaps. For example, only 1 RCT out of the 28 RCTs used fresh fruit in the form of berry pulp [55]; most RCTs used freeze-dried berries [29,31,35,39,40,43,46,47,52,53], berry extract [30,32,33,34,36,41,42,48,50,56], or berry juice [37,38,44,45,49,51,54]. Regarding formulations, 71% of the RCTs using juice [37,38,44,45,51], 60% of the RCTs using freeze-dried berries [29,31,39,40,52,53], and 30% of the RCTs using berry extracts [30,36,48] reported a statistically significant effect on biomarkers of oxidative stress, respectively. The majority of the RCTs using freeze-dried berries advised study subjects to reconstitute with water and to consume as a beverage. Clarification is needed as to whether berries consumed as a reconstituted freeze-dried berry beverage versus 100% juice differentially affect biomarkers of oxidative stress. The freeze-dried berry beverages included fiber, which may affect several physiological systems. The latest sequencing techniques allow for the identification of microbiota present in the intestinal tract, which leads to greater awareness of the role of fiber through its effects on the microbiota. In addition, fiber’s metabolites are thought to play a major role in the health benefits derived from fiber intake [57]. Freeze-dried berries and berry juice may be more promising interventions versus berry extracts when evaluating biomarkers of oxidative stress. Research results are conflicting, as a recent meta-analysis of RCTs showed that both dietary polyphenols from whole foods and polyphenol extracts may be effective in lowering cardiometabolic risk factors such as blood pressure, flow-mediated dilation, and lipid concentrations, though the authors suggest that results must be interpreted with caution due to high heterogeneity and risk of bias among studies [10]. The most common berry used in RCTs was the blueberry, with six studies [32,35,43,47,52,54], then açaí [37,45,55], aronia (chokeberry) [51,53,56], blackcurrant [41,42,44], and cranberry [34,40,48] in three RCTs each. Only one RCT included strawberries alone [31], though two studies included strawberries in mixed berry studies [49,50]. In recent years, there has been much interest in E. oleracea Mart., also known as açaí, which are native to the Amazonia and Atlantic Forest Regions and are fruits of palm trees. An integrative review of human clinical trials has suggested that açaí may contribute to improved antioxidant capacity, metabolic stress, and inflammation [58], a conclusion similar to that of the three RCTs of açaí evaluated in the current systematic review. Additionally, the intervention duration of the RCTs ranged from 7 days to 24 weeks. Some 71% of RCTs had an intervention duration of >4 weeks to 12 weeks, with only one RCT including an intervention that lasted >3 months [35].

Interestingly, almost 60% of RCTs were conducted in adults aged <50 years, even though increased oxidative stress, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular diseases, and various cancers, occurs more frequently in adults aged 65 years and above. The majority (64%) of the subjects in the RCTs were those at risk for diseases such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes; 75% were either overweight or obese. Type 2 diabetes and obesity are known to alter absorption and metabolism, which may affect the bioavailability and effectiveness of polyphenols. The beneficial health effects of anthocyanins are dependent upon their bioavailability. Less than 2% of anthocyanins may be found in the blood or urine after dietary intake, which suggests low bioavailability. Anthocyanins go through several biotransformations in the small and large intestines; only a small percentage of the anthocyanins remain nonmetabolized. However, some research suggests that anthocyanin metabolites may contribute to beneficial health effects [59].

Many RCTs were conducted in North America and Europe, with few conducted in Asia, the Middle East, Oceana, and South America. No RCTs were conducted in Africa. Further, only four RCTs used a sample size calculation for biomarkers of oxidative stress [34,37,39,55].

Generally, the impact of berry consumption on oxidative stress biomarkers reported in the RCTs included here was either beneficial or null. Of the approximately 56 oxidative stress biomarkers reported by the 28 studies, 32% of the biomarkers were reported to have statistically significant beneficial results, and 68% of the biomarkers were reported as having no statistically significant differences. One out of six blueberry RCTs showed a statistically significant beneficial effect on a biomarker of oxidative stress, H2O2-induced DNA damage [52]. Three açaí RCTs reported beneficial effects on antioxidants (catalase, total antioxidant capacity and glutathione), isoprostanes and malondialdehyde [37,45,55]; two out of three aronia (chokeberry) RCTs reported favorable effects on TBARS [51] and glutathione [53]; one out of the three blackcurrant RCTs reported a significant decrease in isoprostanes [44]; and two out of three cranberry RCTs reported beneficial changes in isoprostanes [40] and antioxidants (SOD and TAC) [48].

The large number of biomarkers of oxidative stress reported in the RCTs reviewed render the identification of clear antioxidant effects of berries difficult. Further complicating this endeavor are the different methodologies used to measure biomarkers (e.g., mass spectroscopy vs. enzyme-linked immunoassay kits) and the fact that individual RCTs include multiple biomarkers. RCTs in this and another recent review predominantly reported on blood antioxidants, isoprostanes, malondialdehyde, and oxidized LDL [6]. Isoprostane analysis via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry is an established and accurate methodology [60,61,62,63]. Analysis of antioxidant capacity via electrochemical/chemical methods and oxidized LDL via isolation and fractionation are also well described [64,65,66]. Moving forward toward a more standardized reporting of oxidative stress biomarkers and perhaps consistency across RCTs would require investigators to select a small number of biomarkers linked with human health outcomes that may be measured using the most accurate methods. For example, F2-isoprostane levels have been shown to be associated with metabolic syndrome, and are optimally measured using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assays [61,63].

A factor contributing to null findings across RCTs may be inadequate power, as only 4 (14%) out of 28 studies determined a sample size calculation for biomarkers of oxidative stress. RCTs should have enough power to show the potential effect of the intervention. A recent statistical commentary provided guidance for efficient sample size determination for RCTs, focusing on parallel and crossover designs [67]. For the current systematic review, two out of four RCTs that reported a sample size calculation found statistically significant results. De Liz et al. reported that consuming 200 mL acai juice, containing 100 mg anthocyanins, for 12 weeks increased catalase, TAC, and glutathione in healthy subjects [37]. Espinosa-Moncada et al. found that after 4 weeks of consuming 200 g of agraz (Andean berry), containing 76 mg anthocyanins, TAC was significantly increased and 8-OHdG was significantly decreased in males with metabolic syndrome [39]. However, Chew et al. found no statistically significant results for 8-OHdG in obese subjects consuming a 450 mL cranberry extract beverage, containing 6.22 mg anthocyanins, daily for 8 weeks [34]. Interestingly, Terrazas et al. reported a sample size calculation for DNA damage with no statistically significant effects in healthy male cyclists consuming 400 g açai pulp, containing 71 mg anthocyanins, for 15 days [55]. However, the same study showed that açai pulp decreased lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde) and increased antioxidant capacity. This increased antioxidant capacity, which provides the first line of antioxidant defense mechanisms, may also mediate effects on lipid peroxidation [3].

Another factor contributing to the lack of consistent findings across RCTs may be related to differences in intestinal microbiota profiles. Microbial transformation of dietary polyphenols, including anthocyanins, into secondary metabolites is important to the bioavailability and bioactivity of polyphenols [68,69,70,71]. Evidence also shows that dietary polyphenols modify the intestinal microbiota population. Some studies have demonstrated a significant mediating effect of microbiota on outcomes such as blood pressure, inflammatory status, and intestinal integrity [72,73,74,75]. Despite the known association of microbiota characteristics with the health outcomes of polyphenol-rich diets, none of the studies we reviewed included intestinal microbiota as a measured outcome variable. In a previous systematic review, we presented the limited number of RCTs that included microbiota as a factor in the relationship between polyphenol intake and blood pressure [76]. We suggest that results of RCTs testing the effect of berries on oxidative stress biomarkers might be more consistent if the microbiota profiles of participants were assessed and included in the analysis. Another limitation is the lack of stratification by sex in the articles reviewed. Biomarkers of oxidative stress have been shown to be higher in females than males [77].

The strengths and limitations of this study design warrant consideration. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of RCTs in humans evaluating the effects of berry consumption on biomarkers of oxidative stress in the last 10 years. RCTs are considered the optimal study design to determine causality [78]. We carefully followed the rigorous methodology of the Cochrane collaboration for systematic reviews for interventions [79]. The search strategy applied was thorough, and involved computerized and manual searches. In addition, Covidence, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, available at www.covidence.org (an online systematic review software for deduplication, screening, data extraction, and quality assessment) was utilized, which assists with efficiency in conducting systematic reviews and may ultimately decrease researcher errors. The primary limitation of this study is the heterogeneity across RCTs, such as differing berry interventions and preparations, varying subject characteristics, and differing methodologies that measure oxidative stress biomarkers, and a lack of sample size determination for oxidative stress biomarkers; therefore, caution should be used when interpreting results and conclusions.

5. Conclusions

Overall, evidence reviewed in the study suggests that 32% of oxidative stress biomarkers reported by the 28 RCTs showed statistically significant beneficial results, and 68% oxidative stress biomarkers showed no statistically significant differences. More well-designed and longer-term berry RCTs are needed to evaluate biomarkers of oxidative stress, especially in females and older adults, utilizing a sample size calculation for determining study power.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.S., M.S. and C.B.; methodology, K.S.S., M.S., C.B. and K.M.; formal analysis, K.S.S., M.S., C.B., G.B. and K.M.; data curation, K.S.S., M.S., C.B., G.B. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S.S., M.S., C.B. and K.M.; writing—K.S.S., M.S., C.B., G.B. and K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was a secondary analysis of published studies that were all conducted with the approval of an ethics committee and in participants who provided informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available within the article and may be obtained from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bakhtina, A.A.; Pharaoh, G.A.; Campbell, M.D.; Keller, A.; Stuppard, R.S.; Marcinek, D.J.; Bruce, J.E. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial interactome remodeling is linked to functional decline in aged female mice. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajam, Y.A.; Rani, R.; Ganie, S.Y.; Sheikh, T.A.; Javaid, D.; Qadri, S.S.; Pramodh, S.; Alsulimani, A.; Alkhanani, M.F.; Harakeh, S.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatner, S.F.; Zhang, J.; Oydanich, M.; Berkman, T.; Naftalovich, R.; Vatner, D.E. Healthful aging mediated by inhibition of oxidative stress. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D. Plant Foods, Antioxidant Biomarkers, and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality: A Review of the Evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S404–S421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Escalante, M.L.; Coop-Gamas, F.; Cervantes-Rodriguez, M.; Mendez-Iturbide, D.; Aranda-González, I.I. The effect of diet on oxidative stress and metabolic diseases-Clinically controlled trials. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.; Rexrode, K.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B. Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS. FoodData Central. 2019. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kiyimba, T.; Yiga, P.; Bamuwamye, M.; Ogwok, P.; Van der Schueren, B.; Matthys, C. Efficacy of Dietary Polyphenols from Whole Foods and Purified Food Polyphenol Extracts in Optimizing Cardiometabolic Health: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins-Nature’s Bold, Beautiful, and Health-Promoting Colors. Foods 2019, 8, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Degeneve, A.; Mullen, W.; Crozier, A. Identification of flavonoid and phenolic antioxidants in black currants, blueberries, raspberries, red currants, and cranberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3901–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tian, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y. Anthocyanins, Anthocyanin-Rich Berries, and Cardiovascular Risks: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 44 Randomized Controlled Trials and 15 Prospective Cohort Studies. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 747884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, T.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Chen, C.O.; Crowe-White, K.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Johnson, E.; Lewis, R.; et al. Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2174–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogiatzoglou, A.; Mulligan, A.A.; Lentjes, M.A.; Luben, R.N.; Spencer, J.P.; Schroeter, H.; Khaw, K.T.; Kuhnle, G.G. Flavonoid intake in European adults (18 to 64 years). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovaskainen, M.L.; Torronen, R.; Koponen, J.M.; Sinkko, H.; Hellstrom, J.; Reinivuo, H.; Mattila, P. Dietary intake and major food sources of polyphenols in Finnish adults. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture ARS. Flavonoid Intakes from Food and Beverages: Mean Amounts Consumed per Individual, by Gender and Age, What We Eat in America, NHANES 2017–2018. 2022. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/fndds-flavonoid-database/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.K. Review of Functional and Pharmacological Activities of Berries. Molecules 2021, 26, 3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njus, D.; Kelley, P.M.; Tu, Y.J.; Schlegel, H.B. Ascorbic acid: The chemistry underlying its antioxidant properties. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 159, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Liu, D. Dietary antiaging phytochemicals and mechanisms associated with prolonged survival. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent Research on the Health Benefits of Blueberries and Their Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Marino, M.; Venturi, S.; Tucci, M.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Riso, P.; Porrini, M.; Del Bo, C. Blueberries and their bioactives in the modulation of oxidative stress, inflammation and cardio/vascular function markers: A systematic review of human intervention studies. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 111, 109154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onali, T.; Kivimaki, A.; Mauramo, M.; Salo, T.; Korpela, R. Anticancer Effects of Lingonberry and Bilberry on Digestive Tract Cancers. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; Group, P.-S. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Glanville, J.; Briscoe, S.; Featherstone, R.; Littlewood, A.; Marshall, C.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Noel-Storr, A.; Paynter, R.; Rader, T.; et al. Chapter 4: Searching for and Selecting Studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3 (updated February 2022); Higgins, J.P.T., Thomasm, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane, Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 21, pp. 1–148. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevstrom, L.; Bergh, C.; Landberg, R.; Wu, H.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Waldenborg, M.; Magnuson, A.; Blanc, S.; Frobert, O. Freeze-dried bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) dietary supplement improves walking distance and lipids after myocardial infarction: An open-label randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Res. 2019, 62, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, S.; Soltani, R.; Mirvakili, S.; Sarrafzadegan, N. Evaluation of the effect of Vaccinium arctostaphylos L. fruit extract on serum inflammatory biomarkers in adult hyperlipidemic patients: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Betts, N.M.; Nguyen, A.; Newman, E.D.; Fu, D.; Lyons, T.J. Freeze-dried strawberries lower serum cholesterol and lipid peroxidation in adults with abdominal adiposity and elevated serum lipids. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowtell, J.L.; Aboo-Bakkar, Z.; Conway, M.E.; Adlam, A.R.; Fulford, J. Enhanced task-related brain activation and resting perfusion in healthy older adults after chronic blueberry supplementation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.W.; Chu, T.T.W.; Choi, S.W.; Benzie, I.F.F.; Tomlinson, B. Impact of short-term bilberry supplementation on glycemic control, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and antioxidant status in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 3236–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, B.; Mathison, B.; Kimble, L.; McKay, D.; Kaspar, K.; Khoo, C.; Chen, C.O.; Blumberg, J. Chronic consumption of a low calorie, high polyphenol cranberry beverage attenuates inflammation and improves glucoregulation and HDL cholesterol in healthy overweight humans: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, P.J.; van der Velpen, V.; Berends, L.; Jennings, A.; Feelisch, M.; Umpleby, A.M.; Evans, M.; Fernandez, B.O.; Meiss, M.S.; Minnion, M.; et al. Blueberries improve biomarkers of cardiometabolic function in participants with metabolic syndrome-results from a 6-month, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1535–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davinelli, S.; Bertoglio, J.C.; Zarrelli, A.; Pina, R.; Scapagnini, G. A Randomized Clinical Trial Evaluating the Efficacy of an Anthocyanin-Maqui Berry Extract (Delphinol(R)) on Oxidative Stress Biomarkers. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34 (Suppl. S1), 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Liz, S.; Cardoso, A.L.; Copetti, C.L.K.; Hinnig, P.F.; Vieira, F.G.K.; da Silva, E.L.; Schulz, M.; Fett, R.; Micke, G.A.; Di Pietro, P.F. Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) and jucara (Euterpe edulis Mart.) juices improved HDL-c levels and antioxidant defense of healthy adults in a 4-week randomized cross-over study. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3629–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhlasi, G.; Shidfar, F.; Agah, S.; Merat, S.; Hosseini, A.F. Effects of Pomegranate and Orange Juice on Antioxidant Status in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2015, 85, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Moncada, J.; Marin-Echeverri, C.; Galvis-Perez, Y.; Ciro-Gomez, G.; Aristizabal, J.C.; Blesso, C.N.; Fernandez, M.L.; Barona-Acevedo, J. Evaluation of Agraz Consumption on Adipocytokines, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress Markers in Women with Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, D.S.; Zhang, D.J.; Beyl, R.S.; Greenway, F.L.; Khoo, C. Effect of daily consumption of cranberry beverage on insulin sensitivity and modification of cardiovascular risk factors in adults with obesity: A pilot, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, R.D.; Lyall, K.A.; Wells, R.W.; Sawyer, G.M.; Lomiwes, D.; Ngametua, N.; Hurst, S.M. Daily Consumption of an Anthocyanin-Rich Extract Made From New Zealand Blackcurrants for 5 Weeks Supports Exercise Recovery Through the Management of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: A Randomized Placebo Controlled Pilot Study. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.T.; Flieller, E.B.; Dillon, K.J.; Leverett, B.D. Black Currant Nectar Reduces Muscle Damage and Inflammation Following a Bout of High-Intensity Eccentric Contractions. J. Diet. Suppl. 2016, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.A.; Figueroa, A.; Navaei, N.; Wong, A.; Kalfon, R.; Ormsbee, L.T.; Feresin, R.G.; Elam, M.L.; Hooshmand, S.; Payton, M.E.; et al. Daily blueberry consumption improves blood pressure and arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with pre- and stage 1-hypertension: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ray, S.; Craigie, A.M.; Kennedy, G.; Hill, A.; Barton, K.L.; Broughton, J.; Belch, J.J. Lowering of oxidative stress improves endothelial function in healthy subjects with habitually low intake of fruit and vegetables: A randomized controlled trial of antioxidant- and polyphenol-rich blackcurrant juice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 72, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Simbo, S.Y.; Fang, C.; McAlister, L.; Roque, A.; Banerjee, N.; Talcott, S.T.; Zhao, H.; Kreider, R.B.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U. Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) beverage consumption improves biomarkers for inflammation but not glucose- or lipid-metabolism in individuals with metabolic syndrome in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3097–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin-Echeverri, C.; Blesso, C.N.; Fernandez, M.L.; Galvis-Perez, Y.; Ciro-Gomez, G.; Nunez-Rangel, V.; Aristizabal, J.C.; Barona-Acevedo, J. Effect of Agraz (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) on High-Density Lipoprotein Function and Inflammation in Women with Metabolic Syndrome. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnulty, L.S.; Collier, S.R.; Landram, M.J.; Whittaker, D.S.; Isaacs, S.E.; Klemka, J.M.; Cheek, S.L.; Arms, J.C.; McAnulty, S.R. Six weeks daily ingestion of whole blueberry powder increases natural killer cell counts and reduces arterial stiffness in sedentary males and females. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, M.B.R.; Razzaq, B.A.; Al-Naqqash, M.; Jasim, S.Y. Effects of Cranberry-PACs against Urinary Problems associated with Radiotherapy in Iraqi Patients with Bladder Carcinoma. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2016, 39, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, A.; Salo, I.; Plaza, M.; Bjorck, I. Effects of a mixed berry beverage on cognitive functions and cardiometabolic risk markers; A randomized cross-over study in healthy older adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paquette, M.; Medina Larque, A.S.; Weisnagel, S.J.; Desjardins, Y.; Marois, J.; Pilon, G.; Dudonne, S.; Marette, A.; Jacques, H. Strawberry and cranberry polyphenols improve insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant, non-diabetic adults: A parallel, double-blind, controlled and randomised clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, S.; Arsic, A.; Glibetic, M.; Cikiriz, N.; Jakovljevic, V.; Vucic, V. The effects of polyphenol-rich chokeberry juice on fatty acid profiles and lipid peroxidation of active handball players: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 94, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riso, P.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Del Bo, C.; Martini, D.; Campolo, J.; Vendrame, S.; Moller, P.; Loft, S.; De Maria, R.; Porrini, M. Effect of a wild blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) drink intervention on markers of oxidative stress, inflammation and endothelial function in humans with cardiovascular risk factors. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangild, J.; Faldborg, A.; Schousboe, C.; Fedder, M.D.K.; Christensen, L.P.; Lausdahl, A.K.; Arnspang, E.C.; Gregersen, S.; Jakobsen, H.B.; Knudsen, U.B.; et al. Effects of Chokeberries (Aronia spp.) on Cytoprotective and Cardiometabolic Markers and Semen Quality in 109 Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Danish Men: A Prospective, Double-Blinded, Randomized, Crossover Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stote, K.S.; Sweeney, M.I.; Kean, T.; Baer, D.J.; Novotny, J.A.; Shakerley, N.L.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Carrico, P.M.; Melendez, J.A.; Gottschall-Pass, K.T. The effects of 100% wild blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) juice consumption on cardiometablic biomarkers: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in adults with increased risk for type 2 diabetes. BMC Nutr. 2017, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrazas, S.; Galan, B.S.M.; De Carvalho, F.G.; Venancio, V.P.; Antunes, L.M.G.; Papoti, M.; Toro, M.J.U.; da Costa, I.F.; de Freitas, E.C. Acai pulp supplementation as a nutritional strategy to prevent oxidative damage, improve oxidative status, and modulate blood lactate of male cyclists. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 2985–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Vance, T.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.G.; Caceres, C.; Wang, Y.; Hubert, P.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Chun, O.K.; Bolling, B.W. Aronia berry polyphenol consumption reduces plasma total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in former smokers without lowering biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Res. 2017, 37, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.D.; Lupton, J.R. Dietary Fiber. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2553–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, S.L.; Copetti, C.L.K.; Cardoso, A.L.; Di Pietro, P.F. Biological activities of acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) and jucara (Euterpe edulis Mart.) intake in humans: An integrative review of clinical trials. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 1375–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redan, B.W.; Buhman, K.K.; Novotny, J.A.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Altered Transport and Metabolism of Phenolic Compounds in Obesity and Diabetes: Implications for Functional Food Development and Assessment. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, J.M.; Lee, Y.Y.; Durand, T.; Lee, J.C. Special Issue on “Analytical Methods for Oxidized Biomolecules and Antioxidants” The use of isoprostanoids as biomarkers of oxidative damage, and their role in human dietary intervention studies. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klawitter, J.; Haschke, M.; Shokati, T.; Klawitter, J.; Christians, U. Quantification of 15-F2t-isoprostane in human plasma and urine: Results from enzyme-linked immunoassay and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry cannot be compared. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 25, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.L. Classifying oxidative stress by F2-Isoprostane levels in human disease: The re-imagining of a biomarker. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 897–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van ’t Erve, T.J.; Kadiiska, M.B.; London, S.J.; Mason, R.P. Classifying oxidative stress by F2-isoprostane levels across human diseases: A meta-analysis. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluganti Narasimhulu, C.; Parthasarathy, S. Preparation of LDL, Oxidation, Methods of Detection, and Applications in Atherosclerosis Research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2419, 213–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadea, P.; Skipitari, M.; Kalaitzopoulou, E.; Varemmenou, A.; Spiliopoulou, M.; Papasotiriou, M.; Papachristou, E.; Goumenos, D.; Onoufriou, A.; Rosmaraki, E.; et al. Methods on LDL particle isolation, characterization, and component fractionation for the development of novel specific oxidized LDL status markers for atherosclerotic disease risk assessment. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1078492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candel, M.; van Breukelen, G.J.P. Best (but oft forgotten) practices: Efficient sample sizes for commonly used trial designs. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 1063–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, B.; Periago, P.; Espin, J.C.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A. Identification of urolithin a as a metabolite produced by human colon microflora from ellagic acid and related compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 5571–5576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espin, J.C.; Gonzalez-Sarrias, A.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A. The gut microbiota: A key factor in the therapeutic effects of (poly)phenols. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 139, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, S.V.; Macovei, I.; Bujor, A.; Miron, A.; Skalicka-Wozniak, K.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Trifan, A. Bioactivity of dietary polyphenols: The role of metabolites. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 626–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duynhoven, J.; Vaughan, E.E.; Jacobs, D.M.; Kemperman, R.A.; van Velzen, E.J.; Gross, G.; Roger, L.C.; Possemiers, S.; Smilde, A.K.; Dore, J.; et al. Metabolic fate of polyphenols in the human superorganism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108 (Suppl. S1), 4531–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto-Ordonez, M.; Urpi-Sarda, M.; Queipo-Ortuno, M.I.; Tulipani, S.; Tinahones, F.J.; Andres-Lacueva, C. High levels of Bifidobacteria are associated with increased levels of anthocyanin microbial metabolites: A randomized clinical trial. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espley, R.V.; Butts, C.A.; Laing, W.A.; Martell, S.; Smith, H.; McGhie, T.K.; Zhang, J.; Paturi, G.; Hedderley, D.; Bovy, A.; et al. Dietary flavonoids from modified apple reduce inflammation markers and modulate gut microbiota in mice. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, E.O.; Charlton, K.E.; Probst, Y.C.; Kent, K.; Netzel, M.E. A systematic literature review of the effect of anthocyanins on gut microbiota populations. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, A.; Koch, M.; Bang, C.; Franke, A.; Lieb, W.; Cassidy, A. Microbial Diversity and Abundance of Parabacteroides Mediate the Associations Between Higher Intake of Flavonoid-Rich Foods and Lower Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2021, 78, 1016–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.; Burns, G.; Sturgeon, N.; Mears, K.; Stote, K.; Blanton, C. The Effects of Berry Polyphenols on the Gut Microbiota and Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials in Humans. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunelli, E.; Domanico, F.; La Russa, D.; Pellegrino, D. Sex differences in oxidative stress biomarkers. Curr. Drug Targets 2014, 15, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, T.J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.2 (updated February 2021); Cochrane Wiley-Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).