Effects of Some Olive Fruits-Derived Products on Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Biomarkers on Experimental Diabetes Mellitus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytical Reagents

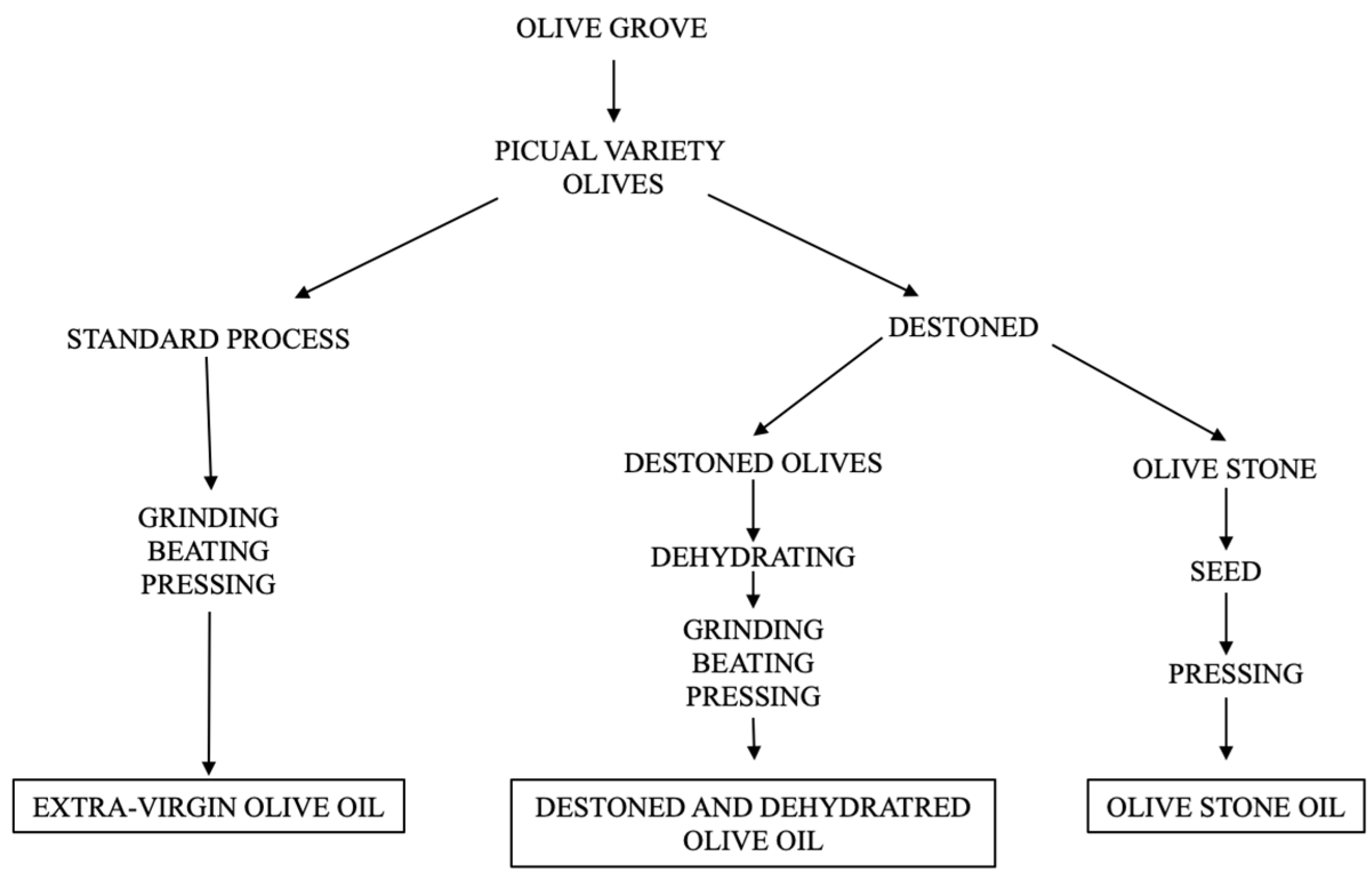

2.2. Olive Fruit Derived Products

- Extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO)

- Olive seed oil (OSO)

- Destoned and dehydrated olive oil (DDOO)

2.3. Experimental Animals

2.4. Experimental Groups

- Healthy non-diabetic rats (NDRs) (10 male rats). They served as controls for the variables determined under normoglycemic conditions. The procedures for administering any types of substances differed from the other groups only in that in this case, physiological saline was administered as a placebo.

- Diabetic control rats (DRs) (10 male rats). These animals were induced with experimental diabetes (see below), none of the study oils were administered, only insulin, with the aim of reducing mortality due to excessively high hyperglycemia.

- Treated diabetic rats. Once the presence of diabetes had been verified in each animal, they were given the oils under study:

- Extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO), at a dose of 0.5 mL/kg/day, by orogastric cannulation, for two months.

- Olive seed oil (OSO), at a dose of 0.5 mL/kg/day, by orogastric cannulation, for two months (10 male rats).

- Destoned and dehydrated olive oil (DDOO) at a dose of 0.5 mL/kg/day by orogastric cannulation for two months (10 male rats).

- Presence of dyspnea, hemorrhage, stupor or cachexia (endpoint criteria).

- Presence of abnormal or increased secretions (no = 0 points; yes = 1 point); isolation or aggressive attitude towards conspecifics and/or investigator (no = 0 points; yes = 1 point); diarrhea (no = 0 points; yes = 1 point). In case of reaching 2 points, the end point criterion would have been applied.

2.5. Induction of Experimental Diabetes Mellitus

2.6. Samples Collection

- Urine, as described in the previous paragraph.

- Blood. Part of the blood was collected in tubes with anticoagulant (sodium citrate 3.8%, ratio 1:10). Part of the blood sample was poured into tubes with resin, without anticoagulation, to form serum; the blood samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and the resulting serum was separated, aliquoted and frozen at −80 °C until the time of analytical determinations.

- A segment of the aorta was obtained 0.5 cm anterior to the bifurcation of the renal arteries.

2.7. Analytical Techniques

2.7.1. Biochemical Profile

2.7.2. Early Variables of Vasculopathy

- Serum-oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), a molecule that is oxidized by free radicals in the early stages of diabetic vasculopathy. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Myeloperoxidase (MPOx), as a leukocyte activation index. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- The vascular adhesion molecule VCAM-1 as a biomarker of endothelial activation in the initial situation of vascular inflammation. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7.3. Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress Variables

- Lipid peroxidation was measured through the determination of reaction products with thiobarbituric acid (TBARS), whose main representative is malondialdehyde (MDA). A commercial colorimetric kit with detection at 532 nm was used, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Global production of oxidative compounds, quantified through the determination of urinary 8-isoprostanes, compounds derived from the interaction of free radicals with arachidonic acid, producing a peroxidation of this fatty acid, which forms 8-epi-PGF2α (8-isoprostanes) without any enzymatic intervention. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- DNA damage caused by free radicals, measured through the determination of 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine. Determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Peroxynitrite production, to assess nitrosative stress, i.e., the formation of free radicals derived from nitric oxide (NO). These radicals nitrate the amino acid tyrosine in a 1:1 ratio, forming 3-nitrotyrosine. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) as an index of the capacity of a sample to exert an antioxidant defense using all its free radical inhibition mechanisms. The TAC assay is based on the reduction of Cu++ to Cu+ by antioxidants such as uric acid and the reaction with a chromogen, determining the absorbance at 490 nm, using a commercial colorimetric kit.

- Concentration of reduced glutathione (GSH), the main tripeptide used by the body as a storehouse of a quantitatively important antioxidant system. A commercial colorimetric test was used, whose instructions were followed to obtain GSH concentrations.

- Glutathione peroxidase activity (GSHpx), an enzyme that oxidizes GSH to GSSG, consuming NADPH, which interacts with free radicals and decreases their oxidative capacity. A commercial colorimetric test based on a spectrophotometric kinetic method was used.

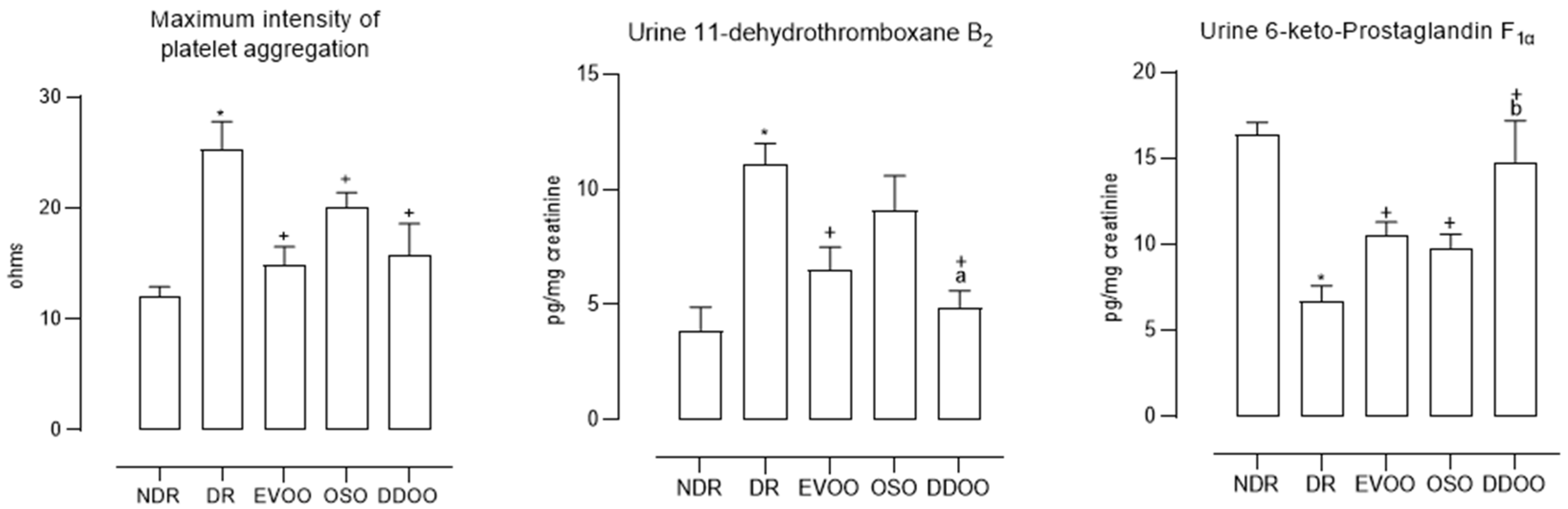

2.7.4. Thrombogenic Related Variables

- Platelet aggregometry. The ability of platelets to aggregate was quantified using a whole-blood electrical impedance aggregometer (Chrono-Log 590, Chrono-Log Corp., Haverton, PA, USA), using collagen (10 µg/mL) as an inducer of platelet aggregation. Maximum platelet aggregation intensity (Imax, ohms) was quantified 10 min after addition of collagen.

- Thromboxane production. The presence of a stable metabolite of thromboxane A2, 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2, a product of the overall formation of this prostanoid in the whole organism, was detected in urine. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Prostacyclin production. The presence of a stable metabolite of prostacyclin, 6-keto-prostaglandin F1α, a product of the overall formation of this prostanoid in the whole organism, was detected in urine. It was determined by commercial ELISA, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

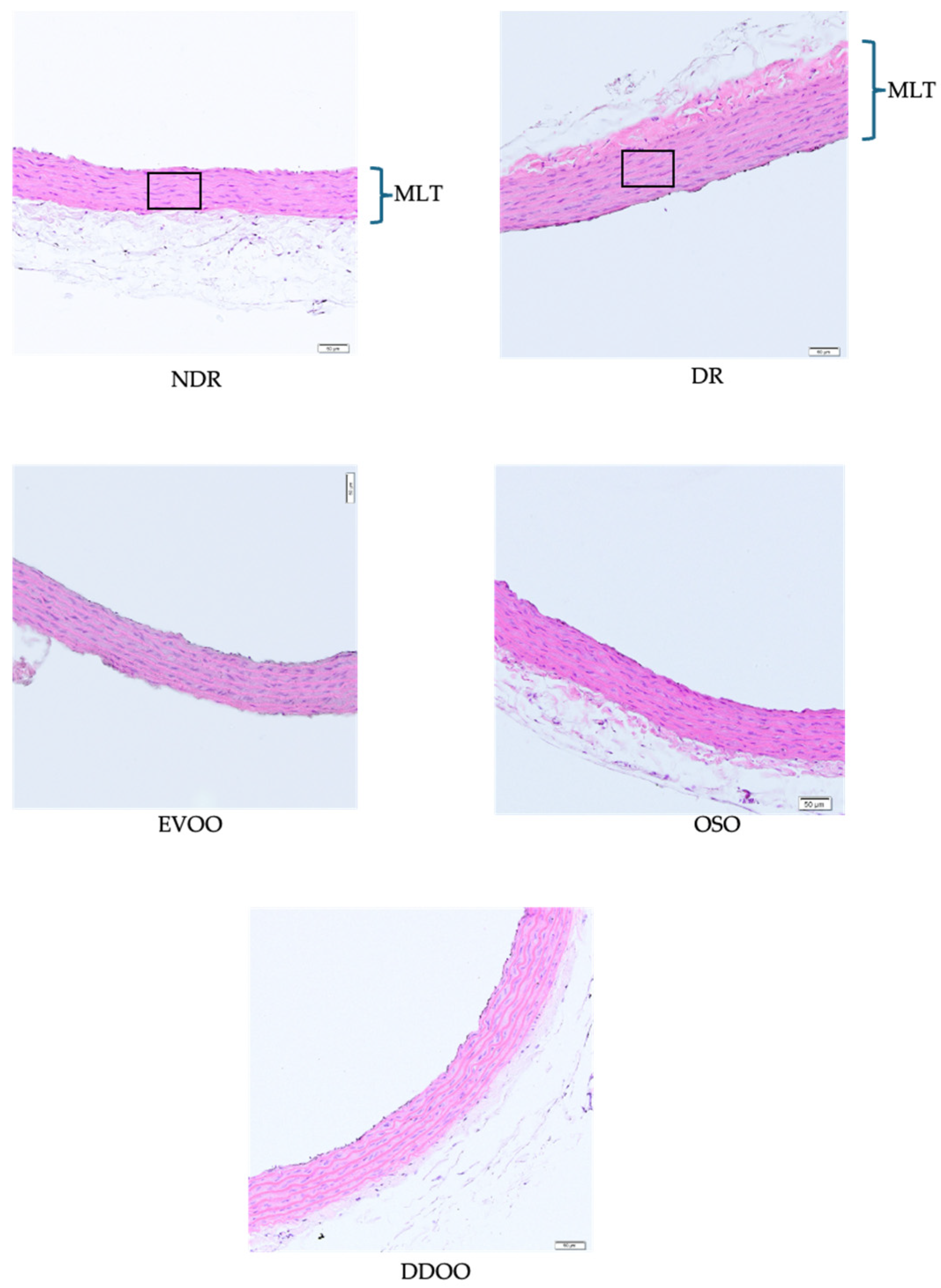

2.7.5. Vascular Morphometric Evaluation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boskou, D.; Clodoveo, M.L. Olive Oil: Processing Characterization, and Health Benefits. Foods 2020, 9, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahdouh, A.; Khay, I.; Le Brech, Y.; El Maakoul, A.; Bakhouya, M. Olive oil industry: A review of waste stream composition, environmental impacts, and energy valorization paths. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 45473–45497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Covas, M.I.; Fiol, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; López-Sabater, M.C.; Vinyoles, E.; et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Ros, E.; PREDIMED INVESTIGATORS. Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Insights from the PREDIMED Study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, L.; Cicerale, L. The Health Benefiting Mechanisms of Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds. Molecules. 2016, 21, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 2020, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, J.P.; Pérez de Algaba, I.; Martín-Aurioles, E.; Arrebola, M.M.; Ortega-Hombrados, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.D.; Fernández-Prior, M.A.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Verdugo, C.; González-Correa, J.A. Extra Virgin Oil Polyphenols Improve the Protective Effects of Hydroxytyrosol in an In Vitro Model of Hypoxia-Reoxygenation of Rat Brain. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Cruz Cortés, J.P.; Vallejo-Carmona, L.; Arrebola, M.M.; Martín-Aurioles, E.; Rodriguez-Pérez, M.D.; Ortega-Hombrados, L.; Verdugo, C.; Fernández-Prior, M.A.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; González-Correa, J.A. Synergistic Effect of 3′,4′-Dihidroxifenilglicol and Hydroxytyrosol on Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress and Some Cardiovascular Biomarkers in an Experimental Model of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Senent, F.; de Roos, B.; Duthie, G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G. Inhibitory and synergistic effects of natural olive phenols on human platelet aggregation and lipid peroxidation of microsomes from vitamin E-deficient rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Villodres, J.A.; Abdel-Karim, M.; De La Cruz, J.P.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.D.; Reyes, J.J.; Guzmán-Moscoso, R.; Rodriguez-Gutierrez, G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; González-Correa, J.A. Effects of hydroxytyrosol on cardiovascular biomarkers in experimental diabetes mellitus. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 37, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, B.; Villanueva, J.J.; López-Villodres, J.A.; De La Cruz, J.P.; Romero, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.D.; Rodriguez-Gutierrez, G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.; González-Correa, J.A. Neuroprotective Effect of Hydroxytyrosol in Experimental Diabetes Mellitus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4378–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, M.D.; López-Villodres, J.A.; Arrebola, M.M.; Martín-Aurioles, E.; Fernández-Prior, A.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Ríos, M.C.; De La Cruz, J.P.; González-Correa, J.A. Nephroprotective Effect of the Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenol Hydroxytyrosol in Type 1-like Experimental Diabetes Mellitus: Relationships with Its Antioxidant Effect. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, M.D.; Pérez de Algaba, I.; Martín-Aurioles, E.; Arrebola, M.M.; Ortega-Hombrados, L.; Verdugo, C.; Fernández-Prior, M.A.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; De La Cruz, J.P.; González-Correa, J.A. Neuroprotective Effect of 3′,4′-Dihydroxyphenylglycol in Type-1-like Diabetic Rats-Influence of the Hydroxytyrosol/3′,4′-dihydroxyphenylglycol Ratio. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pérez, M.D.; Santiago-Corral, L.; Ortega-Hombrados, L.; Verdugo, C.; Arrebola, M.M.; Martín-Aurioles, E.; Fernández-Prior, M.A.; Bermúdez-Oria, A.; De La Cruz, J.P.; González-Correa, J.A. The Effect of the Extra Virgin Olive Oil Minor Phenolic Compound 3′,4′-Dihydroxyphenylglycol in Experimental Diabetic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmo-García, L.; Olmo-Peinado, J.M.; Ruiz-Rueda, J. Olive Subproduct and Procedure for Obtaining the Olive. ES2389816A1, 7 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olmo-García, L.; Monasterio, C.M.; Sánchez-Arévalo, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, R.P.; Olmo-Peinado, J.M.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A. Characterization of New Olive Fruit Derived Products Obtained by Means of a Novel Processing Method Involving Stone Removal and Dehydration with Zero Waste Generation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9295–9306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.; Nascetti, S.; López-Sabater, M.C.; Elosua, R.; Salonen, J.T.; Nyyssönen, K.; Poulsen, H.E.; Zunft, H.-J.F.; Kiesewetter, H.; de la Torre, K.; et al. Changes in LDL fatty acid composition as a response to olive oil treatment are inversely related to lipid oxidative damage: The EUROLIVE study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveras-López, M.J.; Molina, J.J.; Mir, M.V.; Rey, E.F.; Martín, F.; de la Serrana, H.L. Extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) con-sumption and antioxidant status in healthy institutionalized elderly humans. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013, 57, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.L. Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Models in Mice and Rats. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carro, B.; Donate-Correa, J.; Fernández-Villabrille, S.; Martín-Vírgala, J.; Panizo, S.; Carrillo-López, N.; Martínez-Arias, L.; Navarro-González, J.F.; Naves-Díaz, M.; Fernández-Martín, J.L.; et al. Experimental Models to Study Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: Limitations and New Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Chmelir, T.; Chottova Dvorakova, M. Animal Models in Diabetic Research-History, Presence, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, J.P.; Del Río, S.; Arrebola, M.M.; López-Villodres, J.A.; Jebrouni, N.; González-Correa, J.A. Effect of virgin olive oil plus acetylsalicylic acid on brain slices damage after hypoxia-reoxygenation in rats with type 1-like diabetes mellitus. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 471, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Correa, J.A.; Muñoz-Marín, J.; Arrebola, M.M.; Guerrero, A.; Narbona, F.; López-Villodres, J.A.; De La Cruz, J.P. Dietary virgin olive oil reduces oxidative stress and cellular damage in rat brain slices subjected to hypoxia-reoxygenation. Lipids 2007, 42, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Babio, N.; Sorlí, J.V.; Fito, M.; Ros, E.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Effects of a Mediterranean eating plan on the need for glucose-lowering medications in participants with type 2 diabetes: A subgroup analysis of the PREDIMED trial. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, D.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Corbo, F.; Loizzo, M.R. De-stoning technology for improving olive oil nutritional and sensory features: The right idea at the wrong time. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangipane, M.T.; Cecchini, M.; Massantini, R.; Monarca, D. Extra virgin olive oil from destoned fruits to improve the quality of the oil and environmental sustainability. Foods 2022, 11, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandouzi, N.; Zahedmehr, A.; Nasrollahzadeh, J. Effect of polyphenol-rich extra-virgin olive oil on lipid profile and inflammatory biomarkers in patients undergoing coronary angiography: A randomised, controlled, clinical trial. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutruzzolà, A.; Parise, M.; Vallelunga, R.; Lamanna, F.; Gnasso, A.; Irace, C. Effect of Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Butter on Endothelial Function in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Blanch, G.; Sala-Vila, A.; Crespo, J.; Ros, E.; Estruch, R.; Badimon, L. The Mediterranean diet decreases prothrombotic microvesicle release in asymptomatic individuals at high cardiovascular risk. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3377–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Biel-Glesson, S.; Fernandez-Navarro, J.R.; Calleja, M.A.; Espejo-Calvo, J.A.; Gil-Extremera, B.; de la Torre, R.; Fito, M.; Covas, M.I.; Vilchez, P.; et al. Effects of virgin olive oils differing in their bioactive compound contents on biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in healthy adults: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeleso, T.B.; Matumba, M.G.; Mukwevho, E. Oleanolic acid and its derivatives: Biological activities and therapeutic potential in chronic diseases. Molecules 2017, 22, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Prophylactic and therapeutic roles of oleanolic acid and its derivatives in several diseases. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 1767–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Qiu, C.; Zhao, L. Maslinic acid protects vascular smooth muscle cells from oxidative stress through Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2014, 390, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez Martín, A.; de la Puerta Vázquez, R.; Fernández-Arche, A.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V. Supressive effect of maslinic acid from pomace olive oil on oxidative stress and cytokine production in stimulated murine macrophages. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzan, M.; Farzan, M.; Shahrani, M.; Navabi, S.P.; Vardanjani, H.R.; Amini-Khoei, H.; Shabani, S. Neuroprotective properties of Betulin, Betulinic acid, and Ursolic acid as triterpenoids derivatives: A comprehensive review of mechanistic studies. Nutr. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R.; González-Díez, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Herrera, M.D.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Badimon, L. Oleanolic acid induces prostacyclin release in human vascular smooth muscle cells through a cyclooxygenase-2-dependent mechanis. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.M.; Kim, J.; Baek, M.C.; Bae, J.S. Novel factor Xa inhibitor, maslinic acid, with antiplatelet aggregation activity. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 9445–9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkić, T.; Bekvalac, K.; Beara, I.; Plantago, L. Species as modulators of prostaglandin E2 and thromboxane A2 production in inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 262, 113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernáez, Á.; Remaley, A.T.; Farràs, M.; Fernández-Castillejo, S.; Subirana, I.; Schröder, H.; Fernández-Mampel, M.; Muñoz-Aguayo, D.; Sampson, M.; Solà, R.; et al. Olive Oil Polyphenols Decrease LDL Concentrations and LDL Atherogenicity in Men in a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidity (%) | 0.12 | 37.26 | 0.12 |

| Peroxide value (mEqO2/kg) | 8.2 | 3.1 | 12.9 |

| K270 | 0.16 | 1.39 | 0.19 |

| K232 | 1.88 | 3.23 | 1.47 |

| Delta K | <0.01 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| Ethyl oleate (mg/kg) | 7 | 4506 | 5 |

| Waxes (mg/kg) | 34 | 335 | 59 |

| Fatty acid composition | |||

| Myristic acid (%) | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Palmitic acid (%) | 12.24 | 9.86 | 13.62 |

| Palmitoleic acid (%) | 1.10 | 0.26 | 1.22 |

| Margaric acid (%) | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Margaroleic acid (%) | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Stearic Acid (%) | 3.47 | 2.87 | 2.62 |

| Oleic Acid (%) | 76.60 | 68.52 | 77.47 |

| Linoleic Acid (%) | 4.95 | 16.34 | 3.29 |

| Linolenic Acid (%) | 0.71 | 0.29 | 0.82 |

| Arachidic Acid (%) | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.40 |

| Eicosanoic Acid (%) | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.22 |

| Bhenenic Acid (%) | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.11 |

| Lignoceric acid (%) | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.07 |

| Total sterols (mg/kg) | 1367 | 2653 | 1528 |

| Brassicasterol (%) | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Cholesterol (%) | 3.1 | 5.0 | 2.9 |

| Stigmasterol (%) | 0.6 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

| B-Sitosterol (%) | 94.6 | 90.1 | 94.9 |

| D7-Stigmastenol (%) | 0.3 | 1.6 | 0.3 |

| Erythrodiol + Uvaol (%) | 1.0 | 1.1 | 3.6 |

| Total triterpenic acids (mg/kg) | 75.40 | 113.64 | 913.74 |

| Oleanolic acid (mg/kg) | 22.26 | 41.02 | 402.35 |

| Maslinic acid (mg/kg) | 53.14 | 72.62 | 498.14 |

| Ursolic acid (mg/kg) | <5.00 | <5.00 | 13.25 |

| Chlorophyll pigments (mg/kg) | 23.63 | 8.16 | 26.25 |

| Carotenoid pigments (mg/kg) | 7.69 | 9.33 | 8.12 |

| Squalane (mg/100 g) | 440 | 9 | 664 |

| Tocoferoles (mg/kg) | 342 | 11 | 394 |

| Total phenols (mg/kg) | 703.48 ± 11.42 | 530.04 ± 5.63 | 689.39 ± 39.43 |

| 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol | 1.07 | 0.215 | - |

| Hydroxytyrosol | 5.825 | 29.8 | 8.88 |

| Tyrosol | 1.9 | 22.755 | 14.04 |

| Vanillin | - | - | - |

| Vanillic acid | - | 3.13 | - |

| Hydroxytyrosol acetate | - | - | 26.24 |

| Nuzhenide | - | 14.26 | 4.46 |

| Oleuropein derivative 1 | - | 26.76 | - |

| Oleuropein derivative 2 | 36.52 | 23.82 | 22.66 |

| Ligustroside derivative | 49.46 | - | 49.42 |

| Sum | 94.775 | 120.74 | 125.7 |

| Hydroxytyrosol (HT) potential (ppm) | 25 | 45 | 30 |

| % of potential HT approx. | 0.0025 | 0.0045 | 0.0030 |

| NDR | DR | EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Body weight (g) | |||||

| Day 1 | 239 ± 5.1 | 235 ± 4.7 | 233 ± 5.5 | 235 ± 5.3 | 238 ± 6.0 |

| Day 60 | 380 ± 6.1 | 343 ± 16.0 * | 336 ± 30.1 | 317 ± 7.9 | 335 ± 30.0 |

| % increase | 59.2 ± 10.1 | 39.0 ± 15.4 * | 43.3 ± 19.2 | 38.1 ± 16.4 | 47.5 ± 17.0 |

| Food ingested (g/day) | 20.7 ± 2.1 | 28.3 ± 4.4 * | 21.3 ± 2.9 | 22.4 ± 0.8 | 24.3 ± 4.6 |

| Drink ingested (mL/day) | 37.9 ± 14.4 | 105 ± 45.0 * | 80.8 ± 22.8 | 75.5 ± 19.5 | 80.8 ± 15.2 |

| Diuresis (mL/day) | 15.6 ± 1.3 | 34.3 ± 3.2 * | 17.1 ± 1.9 + | 15.9 ± 2.6 + | 17.9 ± 11.7 + |

| NDR | DR | EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 86.4 ± 5.2 | 452 ± 9.4 * | 538 ± 103 | 499 ± 99.0 | 481 ± 104 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 0.7 ± 0.03 * | 0.6 ± 0.06 + | 0.6 ± 0.07 + | 0.5 ± 0.04 + |

| Total proteins (g/dL) | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.5 ± 0.06 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.08 | 1.3 ± 0.06 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 55.5 ± 8.9 | 75.6 ± 3.6 * | 63.0 ± 1.9 + | 73.3 ± 2.6 | 60.9 ± 5.7 + |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 18.7 ± 1.2 | 37.1 ± 4.8 * | 21.6 ± 2.1 + | 24.3 ± 2.3 + | 22.7 ± 1.3 + |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 18.9 ± 3.9 | 17.7 ± 1.6 | 24.9 ± 2.0 + | 25.9 ± 1.7 + | 24.3 ± 3.3 + |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 53.9 ± 11.5 | 130 ± 6.9 * | 95.5 ± 3.1 + | 103 ± 5.7 + | 80.8 ± 5.3 +,a |

| NDR | DR | EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| MPOx (ng/mL) | 0.7 ± 0.07 | 2.7 ± 0.2 * | 1.6 ± 0.5 + | 1.9 ± 0.1 + | 1.8 ± 0.1 + |

| VCAM-1 (ng/mL) | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.7 * | 4.7 ± 1.3 +,a | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 1.1 +,a |

| oxLDL (ng/mL) | 140 ± 20.2 | 257 ± 10.5 * | 214 ± 11.9 + | 227 ± 10.7 + | 202 ± 18.3 + |

| NDR | DR | EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| TBARS (nmol/mg prot) | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 8.6 ± 0.7 * | 3.7 ± 0.9 + | 4.9 ± 0.5 + | 1.7 ± 0.3 +,b |

| 8-OH-dG (ng/mL) | 15.5 ± 0.4 | 25.3 ± 1.6 * | 3.6 ± 0.8 +,a | 6.3 ± 0.9 + | 1.3 ± 0.2 +,a |

| F2-isoprostanes (ng/mg creatinine) | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 47.1 ± 0.6 * | 14.0 ± 0.8 + | 13.4 ± 0.5 + | 14.8 ± 0.8 + |

| 3-nitrotirosine (pg/mL) | 14.2 ± 0.9 | 61.9 ± 3.4 * | 43.8 ± 1.2 + | 44.2 ± 0.8 + | 39.8 ± 2.2 + |

| TAC (U/mL) | 17.1 ± 0.5 | 12.7 ± 0.7 * | 14.9 ± 1.6 + | 15.7 ± 1.5 + | 15.6 ± 0.5 + |

| GSH (nmol/mL) | 121 ± 7.5 | 87.7 ± 6.7 * | 94.8 ± 3.1 | 92.1 ± 3.1 | 123 ± 2.0 +,b |

| GSHpx (nmol/min/mL) | 26.8 ± 1.0 | 7.5 ± 1.2 * | 17.0 ± 3.0 + | 15.9 ± 2.6 + | 24.7 ± 2.2 +,b |

| NDR | DR | EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Arterial wall area (µm2) | 104 ± 5.6 | 144 ± 3.0 * | 114 ± 4.1 + | 115 ± 5.5 + | 117 ± 10.1 + |

| Number of muscular cells (n × 105/µm2) | 40.3 ± 2.1 | 52.9 ± 2.7 * | 38.7 ± 0.9 + | 40.7 ± 1.3 + | 38.7 ± 1.6 + |

| EVOO | OSO | DDOO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid profile (a) | 31.8 | 29.6 | 24.7 |

| Early vascular inflammation biomarkers (b) | 33.0 | 17.1 | 30.2 |

| Oxidative stress (c) | 44.3 | 41.1 | 64.7 |

| Prostanoids (d) | 45.7 | 29.0 | 70.7 |

| Morphology (e) | 25.2 | 23.2 | 24.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De La Cruz, J.P.; Iserte-Terrer, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.D.; Ortega-Hombrados, L.; Sánchez-Tévar, A.M.; Arrebola-Ramírez, M.M.; Fernández-Prior, M.Á.; Verdugo-Cabello, C.; Espejo-Calvo, J.A.; González-Correa, J.A. Effects of Some Olive Fruits-Derived Products on Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Biomarkers on Experimental Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091127

De La Cruz JP, Iserte-Terrer L, Rodríguez-Pérez MD, Ortega-Hombrados L, Sánchez-Tévar AM, Arrebola-Ramírez MM, Fernández-Prior MÁ, Verdugo-Cabello C, Espejo-Calvo JA, González-Correa JA. Effects of Some Olive Fruits-Derived Products on Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Biomarkers on Experimental Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants. 2024; 13(9):1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091127

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe La Cruz, José Pedro, Laura Iserte-Terrer, María Dolores Rodríguez-Pérez, Laura Ortega-Hombrados, Ana María Sánchez-Tévar, María Monsalud Arrebola-Ramírez, María África Fernández-Prior, Cristina Verdugo-Cabello, Juan Antonio Espejo-Calvo, and José Antonio González-Correa. 2024. "Effects of Some Olive Fruits-Derived Products on Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Biomarkers on Experimental Diabetes Mellitus" Antioxidants 13, no. 9: 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091127

APA StyleDe La Cruz, J. P., Iserte-Terrer, L., Rodríguez-Pérez, M. D., Ortega-Hombrados, L., Sánchez-Tévar, A. M., Arrebola-Ramírez, M. M., Fernández-Prior, M. Á., Verdugo-Cabello, C., Espejo-Calvo, J. A., & González-Correa, J. A. (2024). Effects of Some Olive Fruits-Derived Products on Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Biomarkers on Experimental Diabetes Mellitus. Antioxidants, 13(9), 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox13091127