Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Intention: Evidence from Chile, Mexico, and Colombia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

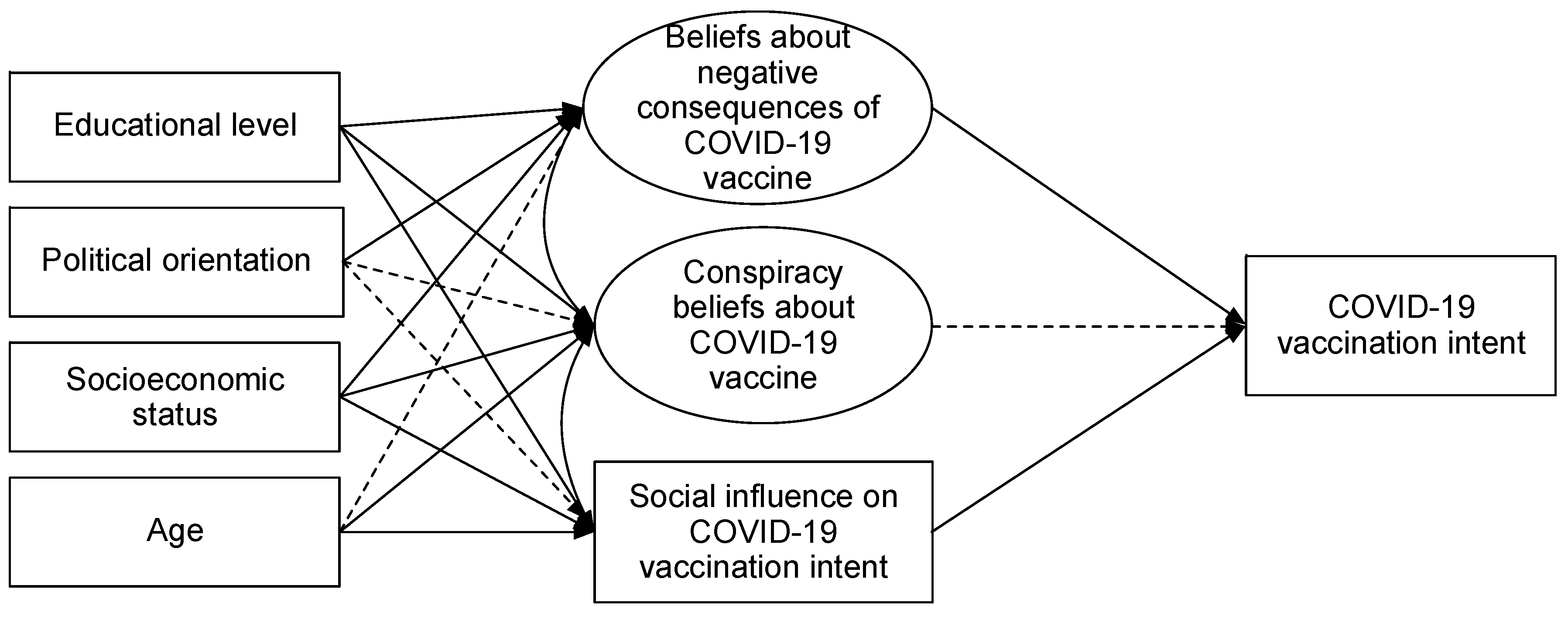

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Beliefs about Negative Consequences of COVID-19 Vaccine

2.2.2. Conspiracy Beliefs about COVID-19 Vaccine

2.2.3. Social Influence on COVID-19 Vaccination Intent

2.2.4. Vaccination Intent against COVID-19

2.2.5. Control Variables

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Invariance Analysis

3.2. Model Predicting COVID-19 Vaccination Intent

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- HM Government. Our Plan to Rebuild: The UK Government’s COVID-19 Recovery Strategy. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-covid-19-recovery-strategy (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M.; Hasell, J.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Rodés-Guirao, L. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.M.; Heesterbeek, H.; Klinkenberg, D.; Hollingsworth, T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Hollingsworth, T.D.; Baggaley, R.F.; Maddren, R.; Vegvari, C. COVID-19 spread in the UK: The end of the beginning? Lancet 2020, 396, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos-Arroyo, J.; de Celis-Herrero, C.P. Severidad, susceptibilidad y normas sociales percibidas como antecedentes de la intención de vacunarse contra COVID-19. Rev. De Salud Pública 2020, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterlini, M. On the front lines of coronavirus: The Italian response to covid-19. BMJ 2020, 368, m1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sabat, I.; Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; van Exel, J.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. United but divided: Policy responses and people’s perceptions in the EU during the COVID-19 outbreak. Health Policy 2020, 124, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackman, A.; Ibañez, A.M.; Izquierdo, A.; Keefer, P.; Moreira, M.M.; Schady, N.; Serebrisky, T. La política pública frente al COVID-19: Recomendaciones para América Latina y el Caribe. Inter-Am. Dev. Bank 2020, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.A.; Franzel, L.; Atwell, J.; Datta, S.D.; Friberg, I.K.; Goldie, S.J.; Reef, S.E.; Schwalbe, N.; Simons, E.; Strebel, P.M.; et al. The estimated mortality impact of vaccinations forecast to be administered during 2011–2020 in 73 countries supported by the GAVI Alliance. Vaccine 2013, 31, B61–B72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Hoq, M.; Measey, M.-A.; Danchin, M. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 21, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/vietnam/news/feature-stories/detail/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Wiysonge, C.S.; Ndwandwe, D.; Ryan, J.; Jaca, A.; Batouré, O.; Anya, B.P.; Cooper, S. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: Could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Hussain, I.; Mahmood, T.; Hayat, K.; Majeed, A.; Imran, I.; Saeed, H.; Iqbal, M.; Uzair, M.; Rehman, A.; et al. A National Survey to Assess the COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Conspiracy Beliefs, Acceptability, Preference, and Willingness to Pay among the General Population of Pakistan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, J.; Vargas, N.; de la Torre, C.; Alvarez, M.M.; Clark, J.L. Engaging Latino Families About COVID-19 Vaccines: A Qualitative Study Conducted in Oregon, USA. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Petit, A.; Causier, C.; East, A.; Jenner, L.; Teale, A.-L.; Carr, L.; Mulhall, S.; et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol. Med. 2020, 52, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, J.-W.; Douglas, K.M. Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Mem. Stud. 2017, 10, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fritsche, I.; Moya, M.; Bukowski, M.; Jugert, P.; de Lemus, S.; Decker, O.; Valor-Segura, I.; Navarro-Carrillo, G. The Great Recession and Group-Based Control: Converting Personal Helplessness into Social Class In-Group Trust and Collective Action. J. Soc. Issues 2017, 73, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pipes, D. Conspiracy: How the paranoid style flourishes and where it comes from. Foreign Aff. 1999, 77, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P.; Maxmen, A. The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories. Nature 2020, 581, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanega, S.; Lynas, M.; Adams, J.; Smolenyak, K.; Insights, C.G. Coronavirus misinformation: Quantifying sources and themes in the COVID-19 ‘infodemic’. JMIR Prepr. 2020, 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baeza-Rivera, M.J.; Salazar-Fernández, C.; Araneda-Leal, L.; Manríquez-Robles, D. To get vaccinated or not? Social psychological factors associated with vaccination intent for COVID-19. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2021, 15, 18344909211051799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, P.; Nera, K.; Delouvée, S. Conspiracy Beliefs, Rejection of Vaccination, and Support for hydroxychloroquine: A Conceptual Replication-Extension in the COVID-19 Pandemic Context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getman, R.; Helmi, M.; Roberts, H.; Yansane, A.; Cutler, D.; Seymour, B. Vaccine Hesitancy and Online Information: The Influence of Digital Networks. Health Educ. Behav. 2017, 45, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čavojová, V.; Šrol, J.; Ballová Mikušková, E. How scientific reasoning correlates with health-related beliefs and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Health Psychol. 2020, 27, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Chapman, C.M.; Alvarez, B.; Bentley, S.; Casara, B.G.S.; Crimston, C.R.; Ionescu, O.; Krug, H.; Selvanathan, H.P.; Steffens, N.K.; et al. To what extent are conspiracy theorists concerned for self versus others? A COVID-19 test case. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolley, D.; Douglas, K.M. The Effects of Anti-Vaccine Conspiracy Theories on Vaccination Intentions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pummerer, L.; Böhm, R.; Lilleholt, L.; Winter, K.; Zettler, I.; Sassenberg, K. Conspiracy Theories and Their Societal Effects During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2021, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soveri, A.; Karlsson, L.C.; Antfolk, J.; Lindfelt, M.; Lewandowsky, S. Unwillingness to engage in behaviors that protect against COVID-19: The role of conspiracy beliefs, trust, and endorsement of complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teovanović, P.; Lukić, P.; Zupan, Z.; Lazić, A.; Ninković, M.; Žeželj, I. Irrational beliefs differentially predict adherence to guidelines and pseudoscientific practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2021, 35, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edberg, M.; Krieger, L. Recontextualizing the social norms construct as applied to health promotion. SSM-Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, D.; Parilli, C.; Scartascini, C.; Simpser, A. Let’s (not) get together! The role of social norms on social distancing during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.D.; Goldstein, N.J. Applying social norms interventions to increase adherence to COVID-19 prevention and control guidelines. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R.I.; Crandall, C.S. Social norms and social influence. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2015, 3, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperson, R.E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H.S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J.X.; Ratick, S. The Social Amplification of Risk: A Conceptual Framework. Risk Anal. 1988, 8, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renn, O.; Burns, W.J.; Kasperson, J.X.; Kasperson, R.E.; Slovic, P. The Social Amplification of Risk: Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Applications. J. Soc. Issues 1992, 48, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Sparks, P. Theory of Planned Behaviour and Health Behaviour. In Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models, 2nd ed.; Conner, P., Norman, P., Eds.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2005; pp. 170–222. [Google Scholar]

- Cookson, D.; Jolley, D.; Dempsey, R.C.; Povey, R. A social norms approach intervention to address misperceptions of anti-vaccine conspiracy beliefs amongst UK parents. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; Agerström, J. Do social norms influence young people’s willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine? Health Commun. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maiman, L.A.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: Origins and Correlates in Psychological Theory. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, H.; Flynn, P.M. The psychology of health: Physical health and the role of culture and behavior. In Handbook of US Latino Psychology: Developmental and Community-Based Perspectives; Villarruel, F.A., Carlo, G., Grau, M., Azmitia, M., Cabrera, N.J., Chahin, T.J., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, P.M.; Betancourt, H.; Ormseth, S.R. Culture, Emotion, and Cancer Screening: An Integrative Framework for Investigating Health Behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 42, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Betancourt, H.; De La Frontera, U. Loma Linda University Investigación Sobre Cultura y Diversidad en Psicología: Una Mirada Desde el Modelo Integrador. Psykhe 2015, 24, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes. México Invierte 2.5% del PIB en Salud, Cuando lo Ideal Sería 6% (o más): OPS. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com.mx/revista-impresa-mexico-invierte-2-5-del-pib-en-salud-cuando-lo-ideal-seria-6-o-mas-ops/ (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Das, K.; Imon, R. A brief review of tests for normality. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, J.B.; Bentler, P.M. Structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed.; Weiner, I., Schinka, J.A., Velicer, W.F., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 607–634. [Google Scholar]

- Milfont, T.L.; Fischer, R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, D.A.; Schmitt, T.A. Testing measurement and structural invariance: Implications for practice. In Handbook of Quantitative Methods for Educational Research; Brill Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 315–345. [Google Scholar]

- Sass, D.A.; Schmitt, T.A.; Marsh, H. Evaluating Model Fit With Ordered Categorical Data Within a Measurement Invariance Framework: A Comparison of Estimators. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, L.; Svetina, D. Measurement Invariance in International Surveys: Categorical Indicators and Fit Measure Performance. Appl. Meas. Educ. 2016, 30, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D.H.; Bucala, R.; Kaplan, M.J.; Nigrovic, P.A. The “Infodemic” of COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 1806–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Dienstmaier, J.M. Teorías de conspiración y desinformación entorno a la epidemia de la COVID-19. Rev. Neuropsiquiatr. 2020, 83, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Mistrust in Governments, the Pre-Existing Condition of Latin America in the COVID-19 Crisis. 2020. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2020/11/1484242 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Biddlestone, M.; Green, R.; Douglas, K.M. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Mercade, P.; Meier, A.N.; Schneider, F.H.; Wengström, E. Prosociality predicts health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2021, 195, 104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, M.M.; Cuadrado, C.; Figueiredo, A.; Crispi, F.; Jiménez-Moya, G.; Andrade, V. Taking Care of Each Other: How Can We Increase Compliance with Personal Protective Measures During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chile? Political Psychol. 2021, 42, 863–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Weisskirch, R.S.; Hurley, E.A.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Park, I.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Umaña-Taylor, A.; Castillo, L.G.; Brown, E.; Greene, A.D. Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2010, 16, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Böhm, R.; Betsch, C. Prosocial vaccination. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 43, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, B.R. How do social norms influence prosocial development? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-A. The Relationship Between Familism and Social Distancing Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic; University of Central Florida: Orlando, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, D.M.; Dorrough, A.R.; Glöckner, A. Prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. The role of responsibility and vulnerability. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, C.; Dryjanska, L.; Suckerman, S. Factors linked to accessing COVID-19 recommendations among working migrants. Public Health Nurs. 2021, 39, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, S.; Bayrak, F.; Yilmaz, O. Psychological correlates of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and preventive measures: Evidence from Turkey. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 40, 5708–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, J.; Pilati, R. COVID-19 as an undesirable political issue: Conspiracy beliefs and intolerance of uncertainty predict adhesion to prevention measures. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.B.; Bell, R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Sharun, K.; Tiwari, R.; Dhawan, M.; Bin Emran, T.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alhumaid, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy—Reasons and solutions to achieve a successful global vaccination campaign to tackle the ongoing pandemic. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3495–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chile | Mexico | Colombia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population (2021) | 19,107,000 | 128,970,000 | 51,450,738 |

| Date of data collection | December 2020 to January 2021 | January to April 2021 | February to April 2021 |

| COVID-19 cases (Accumulated to the time of data collection) | 727,109 | 2,344,755 | 2.859,724 |

| COVID-19 deaths (Accumulated to the time of data collection) | 18,452 | 216,907 | 73,720 |

| Start of mass vaccination process for COVID-19 | 3 February 2021 | 16 February 2021 | 17 February 2021 |

| Vaccinated for COVID-19 to November 2021 | 83.8% | 50.1% | 47.3% |

| Ranking in the comparison of the performance of 102 countries in managing the COVID-19 pandemic according to the Lowy Institute (13 March 2021) | 92 | 101 | 100 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Beliefs about negative consequences of COVID-19 vaccine | - | |||

| 2. Conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19 vaccine | 0.601 ** 0.593 ** 0.551 ** | - | ||

| 3. Social influence on COVID-19 vaccination intent | −0.418 ** −0.231 ** −0.187 ** | −0.581 ** −0.318 ** −0.281 ** | - | |

| 4. COVID-19 vaccination intent | −0.534 ** −0.508 ** −0.439 ** | −0.753 ** −0.652 ** −0.599 ** | 0.742 ** 0.437 ** 0.440 ** | - |

| Mean (SD) | 1.875 (0.924) 1.761 (0.804) 2.156 (0.868) | 2.289 (0.866) 2.308 (0.745) 2.454 (0.783) | 3.853 (1.330) 3.920 (1.205) 3.861 (1.228) | 3.963 (1.234) 4.167 (1.084) 3.912 (1.177) |

| Model | 2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA(90% CI) | SRMR | Model Comparison | ∆CFI | ∆RMSEA | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Full configural invariance | 316.226 ** | 216 | 0.995 | 0.993 | 0.026 (0.019, 0.032) | 0.036 | - | - | - | Accept |

| Model 2: Full metric invariance | 364.137 ** | 230 | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.029 (0.023, 0.035) | 0.038 | Model 2 vs. Model 1 | −0.002 | −0.003 | Accept |

| Model 3: Full scalar invariance | 472.256 ** | 249 | 0.988 | 0.986 | 0.036 (0.031, 0.041) | 0.043 | Model 3 vs. Model 2 | −0.005 | −0.007 | Accept |

| Model 4: Full strict invariance | 553.248 ** | 270 | 0.985 | 0.984 | 0.039 (0.034, 0.044) | 0.049 | Model 4 vs. Model 3 | −0.003 | 0.003 | Accept |

| Model 5: Full structural invariance | 633.440 ** | 300 | 0.982 | 0.983 | 0.040 (0.036, 0.045) | 0.052 | Model 5 vs. Model 4 | −0.003 | 0.001 | Accept |

| Measurement Models Factor Loadings (Standard Error) | Structural Model: COVID-19 Vaccination Intent Standardized Coefficient (Standard Error) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chile | Mexico | Colombia | Chile | Mexico | Colombia | |

| Conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19 vaccine | −0.053 (0.050) | −0.052 (0.050) | −0.054 (0.050) | |||

| 1. The COVID-19 vaccine will contain a microchip to monitor people | 0.796 ** (-) | 0.749 ** (-) | 0.764 ** (-) | |||

| 2. The vaccine against COVID-19 has already been created, but they are withholding it to maintain control of the population | 0.790 ** (0.049) | 0.742 ** (0.049) | 0.758 ** (0.049) | |||

| 3. Big Pharma created COVID-19 to benefit from vaccines | 0.792 ** (0.053) | 0.743 ** (0.053) | 0.759 ** (0.053) | |||

| Beliefs about negative consequences of COVID-19 vaccine | −0.591 ** (0.066) | −0.568 ** (0.066) | −0.589 ** (0.066) | |||

| 1. The COVID-19 vaccine may increase the spread of the virus | 0.680 ** (-) | 0.616 ** (-) | 0.634 ** (-) | |||

| 2. I distrust the long-term effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine | 0.659 ** (0.051) | 0.594 ** (0.051) | 0.613 ** (0.051) | |||

| 3. If I get vaccinated against COVID-19, my chances of contracting the virus increase | 0.719 ** (0.038) | 0.657 ** (0.038) | 0.675 ** (0.038) | |||

| 4. The COVID-19 vaccine will cause more complex effects than the virus can have | 0.847 ** (0.046) | 0.802 ** (0.046) | 0.816 ** (0.046) | |||

| 5. I think the COVID-19 vaccine has more risks than other vaccines | 0.772 ** (0.051) | 0.715 ** (0.051) | 0.732 ** (0.051) | |||

| 6. I am afraid of the possible adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccine | 0.694 ** (0.058) | 0.630 ** (0.058) | 0.649 ** (0.058) | |||

| Social influence on COVID-19 vaccination intent | 0.252 ** (0.023) | 0.248 ** (0.023) | 0.283 ** (0.023) | |||

| R2 | 0.665 | 0.564 | 0.575 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salazar-Fernández, C.; Baeza-Rivera, M.J.; Villanueva, M.; Bautista, J.A.P.; Navarro, R.M.; Pino, M. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Intention: Evidence from Chile, Mexico, and Colombia. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10071129

Salazar-Fernández C, Baeza-Rivera MJ, Villanueva M, Bautista JAP, Navarro RM, Pino M. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Intention: Evidence from Chile, Mexico, and Colombia. Vaccines. 2022; 10(7):1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10071129

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalazar-Fernández, Camila, María José Baeza-Rivera, Marcoantonio Villanueva, Joaquín Alberto Padilla Bautista, Regina M. Navarro, and Mariana Pino. 2022. "Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Intention: Evidence from Chile, Mexico, and Colombia" Vaccines 10, no. 7: 1129. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10071129