Parents’Attitudes, Their Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and the Contributing Factors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Development of Study Tool and Validation

2.4. Contents of theStudy Tool

2.4.1. Demographic Details

2.4.2. Child Immunization History and Parents’ Source of Information Regarding COVID-19

2.4.3. Parents’ Vaccination, Infection Status and Precautionary Measures toward COVID-19

2.4.4. Parents’ Willingness to Vaccinate Children with COVID-19 Vaccine

2.4.5. Parental Attitude toward COVID-19 Vaccination in Children

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Details

3.2. Parents’Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19

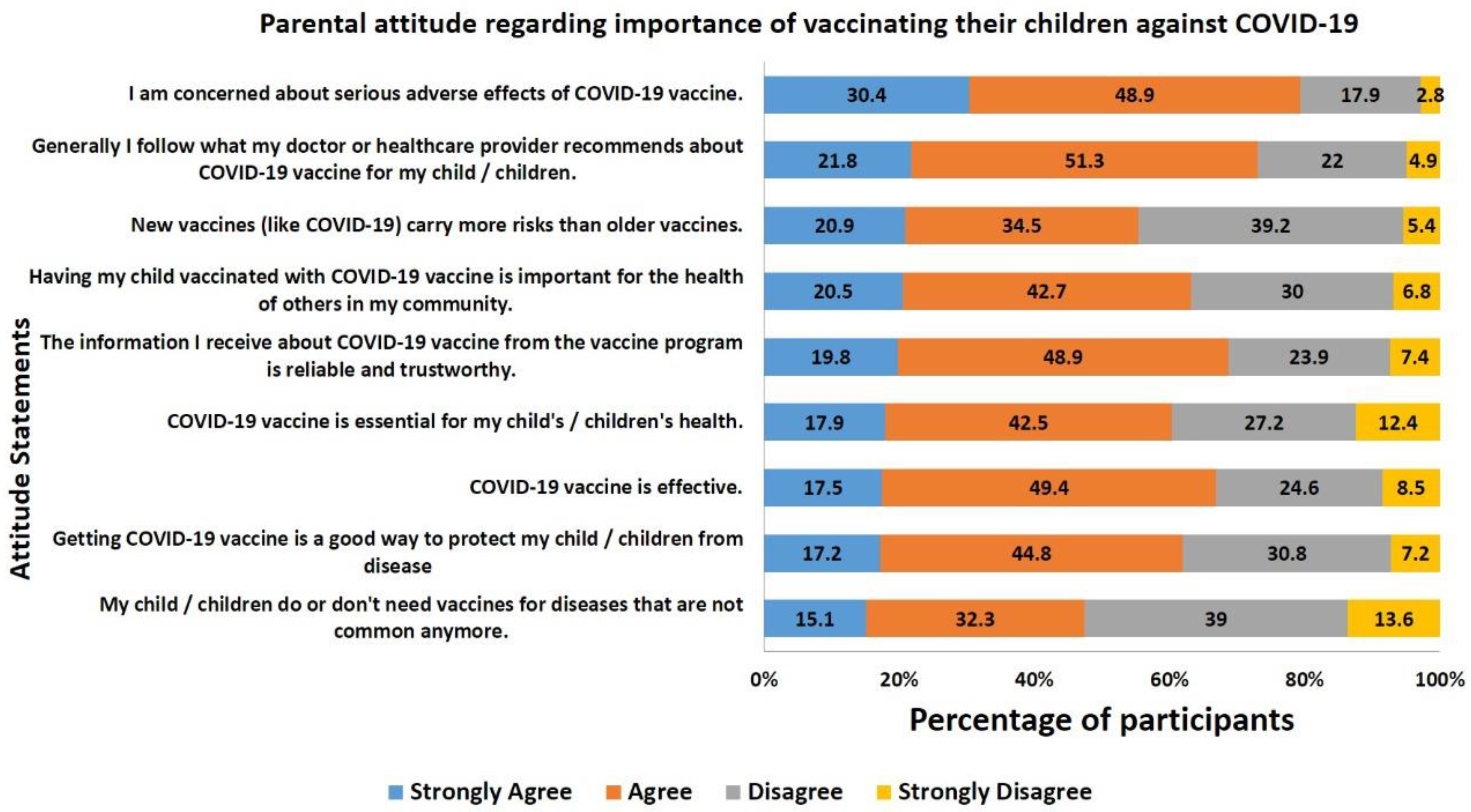

3.3. Vaccine Hesitancy Scale (VHS)—Attitude Regarding the Importance of Vaccinating Children against COVID-19

3.4. Parental Behavior toward COVID-19 Vaccination, Precautionary Measures, and Childhood Vaccination

3.5. Parents’Concerns and Misbelieves Regarding Vaccinating Their Children with COVID-19

3.6. Source of COVID-19 Information

3.7. Determining the Drivers of Parental Willingness to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19

3.8. Multivariate Analysis to Identify the Factors Associated with Parental COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy for Their Children

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Pak, A.; Adegboye, O.A.; Adekunle, A.I.; Rahman, K.M.; McBryde, E.S.; Eisen, D.P. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Whitaker, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Kambhampati, A.; Chai, S.J.; Reingold, A.; Armistead, I.; Kawasaki, B.; Meek, J.; Yousey-Hindes, K.; et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Children Aged <18 Years Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19-COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–July 25, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Mytton, O.T.; Bonell, C.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Ward, J.; Hudson, L.; Waddington, C.; Thomas, J.; Russell, S.; van der Klis, F.; et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection among Children and Adolescents Compared with Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsankov, B.K.; Allaire, J.M.; Irvine, M.A.; Lopez, A.A.; Sauvé, L.J.; Vallance, B.A.; Jacobson, K. Severe COVID-19 Infection and Pediatric Comorbidities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 103, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.A.; Preston-Hurlburt, P.; Dai, Y.; Aschner, C.B.; Cheshenko, N.; Galen, B.; Garforth, S.J.; Herrera, N.G.; Jangra, R.K.; Morano, N.C.; et al. Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Hospitalized Pediatric and Adult Patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eabd5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R.; Kaswandani, N.; Karyanti, M.R.; Setyanto, D.B.; Pudjiadi, A.H.; Hendarto, A.; Djer, M.M.; Prayitno, A.; Yuniar, I.; Indawati, W.; et al. Mortality in Children with Positive SARS-CoV-2 Polymerase Chain Reaction Test: Lessons Learned from a Tertiary Referral Hospital in Indonesia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 107, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, F.S.; Porucznik, C.A.; Veguilla, V.; Stanford, J.B.; Duque, J.; Rolfes, M.A.; Dixon, A.; Thind, P.; Hacker, E.; Castro, M.J.E.; et al. Incidence Rates, Household Infection Risk, and Clinical Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Infection among Children and Adults in Utah and New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, L.A.; Daneman, N.; Schwartz, K.L.; Science, M.; Brown, K.A.; Whelan, M.; Chan, E.; Buchan, S.A. Association of Age and Pediatric Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, F.M. If Young Children’s Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Is Similar to That of Adults, Can Children Also Contribute to Household Transmission? JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farronato, M.; Tadakamadla, S.K.; Ali Quadri, M.F.; Acharya, S.; Tadakamadla, J.; Love, R.M.; Jamal, M.; Mulder, R.; Maspero, C.; Farronato, D.; et al. A Call for Action to Safely Deliver Oral Health Care during and Post COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, A.A. The Progressive Public Measures of Saudi Arabia to Tackle COVID-19 and Limit Its Spread. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Bhattacharya, M.; Agoramoorthy, G.; Lee, S.-S. The Drug Repurposing for COVID-19 Clinical Trials Provide Very Effective Therapeutic Combinations: Lessons Learned from Major Clinical Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 704205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assessment of the Further Spread and Potential Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant of Concern in the EU/EEA, 19th Update. Available online: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/covid-19-omicron-risk-assessment-further-emergence-and-potential-impact (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Harris, R.J.; Hall, J.A.; Zaidi, A.; Andrews, N.J.; Dunbar, J.K.; Dabrera, G. Effect of Vaccination on Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in England. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 759–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Vaccines. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- EMA COVID-19 Vaccines: Development, Evaluation, Approval and Monitoring. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-development-evaluation-approval-monitoring (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- COVID 19 Dashboard: Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://covid19.moh.gov.sa/ (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Joudah, G. Saudi Arabia Promotes Safety of COVID-19 Vaccine for Those Aged 5–11. Arab News, 22 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, N.E. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Health Issues WHO Will Tackle This Year. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Domek, G.J.; O’Leary, S.T.; Bull, S.; Bronsert, M.; Contreras-Roldan, I.L.; Bolaños Ventura, G.A.; Kempe, A.; Asturias, E.J. Measuring Vaccine Hesitancy: Field Testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Survey Tool in Guatemala. Vaccine 2018, 35, 5273–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; Nickels, E.; Jeram, S.; Schuster, M. Mapping Vaccine Hesitancy—Country-Specific Characteristics of a Global Phenomenon. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6649–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Temsah, M.-H.; Alhuzaimi, A.N.; Aljamaan, F.; Bahkali, F.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Alrabiaah, A.; Alhaboob, A.; Bashiri, F.A.; Alshaer, A.; Temsah, O.; et al. Parental Attitudes and Hesitancy about COVID-19 vs. Routine Childhood Vaccinations: A National Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 752323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babicki, M.; Pokorna-Kałwak, D.; Doniec, Z.; Mastalerz-Migas, A. Attitudes of Parents with Regard to Vaccination of Children against COVID-19 in Poland. A Nationwide Online Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Walker, J.L.; Paterson, P. Parents’ and Guardians’ Views on the Acceptability of a Future COVID-19 Vaccine: A Multi-Methods Study in England. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7789–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjefte, M.; Ngirbabul, M.; Akeju, O.; Escudero, D.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Wyszynski, D.F.; Wu, J.W. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Pregnant Women and Mothers of Young Children: Results of a Survey in 16 Countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaceur, S.; Al-Mohaithef, M. Parents’ Willingness to Vaccinate Children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altulahi, N.; AlNujaim, S.; Alabdulqader, A.; Alkharashi, A.; AlMalki, A.; AlSiari, F.; Bashawri, Y.; Alsubaie, S.; AlShahrani, D.; AlGoraini, Y. Willingness, Beliefs, and Barriers Regarding the COVID-19 Vaccine in Saudi Arabia: A Multiregional Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, N.L.; Kusma, J.D.; Heard-Garris, N.; Davis, M.M.; Golbeck, E.; Barrera, L.; Macy, M.L. Parental COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy for Children: Vulnerability in an Urban Hotspot. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Sahin, M.K. Parents’ Willingness and Attitudes Concerning the COVID-19 Vaccine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, P.G.; Shah, M.D.; Delgado, J.R.; Thomas, K.; Vizueta, N.; Cui, Y.; Vangala, S.; Shetgiri, R.; Kapteyn, A. Parents’ Intentions and Perceptions about COVID-19 Vaccination for Their Children: Results from a National Survey. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021052335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- azalghamdi 16-2017. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/915 (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Schulz, W.S.; Chaudhuri, M.; Zhou, Y.; Dube, E.; Schuster, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Wilson, R. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Measuring Vaccine Hesitancy: The Development of a Survey Tool. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kempe, A.; Saville, A.W.; Albertin, C.; Zimet, G.; Breck, A.; Helmkamp, L.; Vangala, S.; Dickinson, L.M.; Rand, C.; Humiston, S.; et al. Parental Hesitancy about Routine Childhood and Influenza Vaccinations: A National Survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, B. The Contribution of Vaccination to Global Health: Past, Present and Future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaffer DeRoo, S.; Pudalov, N.J.; Fu, L.Y. Planning for a COVID-19 Vaccination Program. JAMA 2020, 323, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, O.S.; Alfayez, O.M.; Al Yami, M.S.; Asiri, Y.A.; Almohammed, O.A. Parents’ Hesitancy to Vaccinate Their 5–11-Year-Old Children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: Predictors from the Health Belief Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 842862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsubaie, S.S.; Gosadi, I.M.; Alsaadi, B.M.; Albacker, N.B.; Bawazir, M.A.; Bin-Daud, N.; Almanie, W.B.; Alsaadi, M.M.; Alzamil, F.A. Vaccine Hesitancy among Saudi Parents and Its Determinants. Result from the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Survey Tool: Result from the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Survey Tool. Saudi Med. J. 2019, 40, 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldakhil, H.; Albedah, N.; Alturaiki, N.; Alajlan, R.; Abusalih, H. Vaccine Hesitancy towards Childhood Immunizations as a Predictor of Mothers’ Intention to Vaccinate Their Children against COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1497–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E. What Are the Factors That Contribute to Parental Vaccine-Hesitancy and What Can We Do about It? Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 2584–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olusanya, O.A.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Davis, R.L.; Shaban-Nejad, A. Addressing Parental Vaccine Hesitancy and Other Barriers to Childhood/Adolescent Vaccination Uptake during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 663074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, D.J.; Taylor, J.A.; Mangione-Smith, R.; Solomon, C.; Zhao, C.; Catz, S.; Martin, D. Validity and Reliability of a Survey to Identify Vaccine-Hesitant Parents. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6598–6605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Average Household Monthly Income Saudi Arabia 2018 by Administrative Region. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1124341/saudi-arabia-average-household-monthly-income-by-region/ (accessed on 24 July 2022).

- Zhang, K.C.; Fang, Y.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z. Parental Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination for Children under the Age of 18 Years: Cross-Sectional Online Survey. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2020, 3, e24827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, R.D.; Marneni, S.R.; Seiler, M.; Brown, J.C.; Klein, E.J.; Cotanda, C.P.; Gelernter, R.; Yan, T.D.; Hoeffe, J.; Davis, A.L.; et al. Caregivers’ Willingness to Accept Expedited Vaccine Research during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 2124–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giambi, C.; Fabiani, M.; D’Ancona, F.; Ferrara, L.; Fiacchini, D.; Gallo, T.; Martinelli, D.; Pascucci, M.G.; Prato, R.; Filia, A.; et al. Parental Vaccine Hesitancy in Italy–Results from a National Survey. Vaccine 2018, 36, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustmohammadi, S.; Cherry, J.D. The Sociology of the Antivaccine Movement. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2020, 4, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. The Online Anti-Vaccine Movement in the Age of COVID-19. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e504–e505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Roma, P.; De Giglio, O.; Caggiano, G.; Tafuri, S.; Da Molin, G.; Ferracuti, S.; Montagna, M.T.; Liguori, G.; et al. Knowledge and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination among Undergraduate Students from Central and Southern Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Roma, P.; Ferracuti, S.; Da Molin, G.; Diella, G.; Montagna, M.T.; Orsi, G.B.; Liguori, G.; Napoli, C. Knowledge and Lifestyle Behaviors Related to COVID-19 Pandemic in People over 65 Years Old from Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Roma, P.; Da Molin, G.; Diella, G.; Montagna, M.T.; Ferracuti, S.; Liguori, G.; Orsi, G.B.; Napoli, C. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Elderly: A Cross-Sectional Study in Southern Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Alshareef, N.; El-Sokkary, R.H. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination among Older Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Community-Based Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, Y.S. Acceptability of the COVID-19 Vaccine among Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study of the General Population in the Southern Region of Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2021, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Kaitelidou, D. Uptake of COVID-19 Vaccines among Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, V. COVID-19: Over 90% of Students Aged 12 and over in Saudi Arabia Are Vaccinated. Available online: https://gulfbusiness.com/covid-19-over-90-of-students-aged-12-and-over-in-saudi-arabia-are-vaccinated/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Saudi Arabia: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/emro/country/sa (accessed on 25 July 2022).

| Demographic Information n = 464 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Category | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Age | 25 years and below | 29 | 6.3 |

| 26 to 40 years | 263 | 56.7 | |

| 41 years and above | 172 | 37.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 264 | 56.9 |

| Female | 200 | 43.1 | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 363 | 78.2 |

| Non-Saudi | 101 | 21.8 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 416 | 89.7 |

| Divorced or separated | 48 | 10.3 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 461 | 99.4 |

| Non-Muslim | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Place of Residence | Urban | 419 | 90.3 |

| Rural | 45 | 9.7 | |

| Parents Education | High school or less | 188 | 40.5 |

| College Degree | 157 | 33.8 | |

| Postgraduate or higher | 119 | 25.6 | |

| Family’s Monthly Income | Less than 5000 SR | 92 | 19.8 |

| 5000 to 10,000 SR | 111 | 23.9 | |

| more than 10,000 SR | 123 | 26.5 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 138 | 29.7 | |

| Are you a Health-care professional? | Yes | 166 | 35.8 |

| No | 298 | 64.2 | |

| Job sector | Government | 221 | 47.6 |

| Private | 71 | 15.3 | |

| Self-Employed | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Unemployed | 16 | 3.4 | |

| Retired | 16 | 3.4 | |

| Housewife | 121 | 26.1 | |

| Student | 16 | 3.4 | |

| Number of Children | two or less | 165 | 35.6 |

| 3 to 5 | 224 | 48.3 | |

| 6 to 8 | 68 | 14.7 | |

| More than 8 | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Children of 5–11 years age | Yes | 341 | 73.5 |

| No | 123 | 26.5 | |

| Gender of children | All male | 150 | 32.3 |

| All female | 87 | 18.8 | |

| Both male and female | 227 | 48.9 | |

| Children with chronic diseases? | Yes | 30 | 6.5 |

| No | 434 | 93.5 | |

| Variables | Sub-Group | Willingness to Vaccinate Children against COVID-19 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, as Soon as Possible (%) | Delaying for Few Month (%) | Delaying for Year and Above (%) | Undecided (%) | No, I Might Consider in Future (%) | No, Never (%) | p Value | ||

| Age | 25 years and below | 10 (34.48) | 7 (24.14) | 3 (10.34) | 8 (27.59) | 1 (3.45) | Zero | <0.001 * |

| 26 to 40 years | 54 (20.53) | 33 (12.55) | 15 (5.70) | 93 (35.36) | 25 (9.51) | 43 (16.35) | ||

| 41 years and above | 65 (37.79) | 25 (14.53) | 12 (6.98) | 27 (15.70) | 14 (8.13) | 29 (16.86) | ||

| Gender | Male | 83 (31.44) | 37 (14.02) | 17 (6.44) | 65 (24.62) | 19 (7.20) | 43 (16.29) | 0.257 |

| Female | 46 (23) | 28 (14) | 13 (6.5) | 63 (31.5) | 21 (10.5) | 29 (14.5) | ||

| Nationality | Saudi | 88 (24.24) | 52 (14.33) | 24 (6.61) | 105 (28.93) | 30 (8.26) | 64 (17.63) | 0.016 * |

| Non-Saudi | 41 (40.59) | 13 (12.87) | 6 (5.94) | 23 (22.77) | 10 (9.9) | 8 (7.92) | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 112 (26.92) | 59 (14.08) | 27 (6.49) | 112 (26.92) | 37 (8.89) | 69 (16.59) | 0.397 |

| Divorced or separated | 17 (35.42) | 6 (12.5) | 3 (6.25) | 16 (33.33) | 3 (6.25) | 3 (6.25) | ||

| Religion | Muslim | 129 (27.98) | 64 (13.88) | 29 (6.29) | 127 (27.55) | 40 (8.68) | 72 (15.62) | 0.328 |

| Non-Muslim | Zero | 1 (33.33) | 1 (33.33) | 1 (33.33) | Zero | Zero | ||

| Place of Residence | Urban | 119 (28.4) | 60 (14.32) | 26 (6.21) | 117 (27.92) | 34 (8.11) | 63 (15.04) | 0.636 |

| Rural | 10 (22.22) | 5 (11.11) | 4 (8.89) | 11 (24.44) | 6 (13.33) | 9 (20) | ||

| Parents Education | High school or less | 52 (27.66) | 28 (14.89) | 16 (8.51) | 56 (29.79) | 12 (6.38) | 24 (12.77) | <0.001 * |

| College Degree | 30 (19.11) | 16 (10.19) | 9 (5.73) | 53 (33.76) | 21 (13.38) | 28 (17.83) | ||

| Postgraduate or higher | 47 (39.5) | 21 (17.65) | 5 (4.2) | 19 (15.97) | 7 (5.88) | 20 (16.81) | ||

| Family’s Monthly Income | Less than 5000 SR | 22 (23.91) | 12 (13.04) | 8 (8.7) | 33 (35.87) | 5 (5.43) | 12 (13.04) | <0.001 * |

| 5000 to 10,000 SR | 21 (18.92) | 5 (4.5) | 11 (9.91) | 30 (27.03) | 16 (14.41) | 28 (25.23) | ||

| more than 10,000 SR | 43 (34.96) | 23 (18.7) | 6 (4.88) | 26 (21.14) | 7 (5.69) | 18 (14.63) | ||

| Prefer not to answer | 43 (31.16) | 25 (18.12) | 5 (3.62) | 39 (28.26) | 12 (8.7) | 14 (10.14) | ||

| Are you a Health-care professional? | Yes | 67 (40.36) | 29 (17.47) | 9 (5.42) | 36 (21.69) | 10 (6.02) | 15 (9.04) | <0.001 * |

| No | 62 (20.81) | 36 (12.08) | 21 (7.05) | 92 (30.87) | 30 (10.07) | 57 (19.13) | ||

| Job sector | Government | 75 (33.93) | 28 (12.66) | 11 (4.97) | 53 (23.98) | 24 (10.85) | 30 (13.57) | 0.001 * |

| Private | 14 (19.71) | 10 (14.08) | 5 (7.04) | 20 (28.16) | 9 (12.67) | 13 (18.3) | ||

| Self-Employed | 1 (33.33) | 1 (33.33) | Zero | Zero | Zero | 1 (33.33) | ||

| Unemployed | 4 (25) | Zero | 5 (31.25) | 1 (6.25) | 1 (6.25) | 5 (31.25) | ||

| Retired | Zero | 4 (25) | Zero | 8 (50) | Zero | 4 (25) | ||

| Housewife | 31 (25.61) | 17 (14.04) | 8 (6.61) | 40 (33.05) | 6 (4.95) | 19 (15.7) | ||

| Student | 4 (25) | 5 (31.25) | 1 (6.25) | 6 (37.5) | Zero | Zero | ||

| Number of children | Two or less | 38 (23.03) | 23 (13.93) | 13 (7.87) | 46 (27.87) | 25 (15.15) | 20 (12.12) | <0.001 * |

| 3 to 5 | 79 (35.26) | 24 (10.71) | 13 (5.8) | 64 (28.57) | 11 (4.91) | 33 (14.73) | ||

| 6 to 8 | 11 (16.17) | 14 (20.58) | 4 (5.88) | 17 (25) | 4 (5.88) | 18 (26.47) | ||

| More than 8 | 1 (14.28) | 4 (57.14) | Zero | 1 (14.28) | Zero | 1 (14.28) | ||

| Children of 5–11 years age | Yes | 91 (26.68) | 49 (14.36) | 16 (4.69) | 100 (29.32) | 29 (8.5) | 56 (16.42) | 0.107 |

| No | 38 (30.89) | 16 (13) | 14 (11.38) | 28 (22.76) | 11 (8.94) | 16 (13) | ||

| Gender of children | All male | 47 (31.33) | 21 (14) | 12 (8) | 25 (16.66) | 13 (8.66) | 32 (21.33) | 0.003 * |

| All female | 16 (18.39) | 11 (12.64) | 7 (8.04) | 37 (42.52) | 4 (4.59) | 12 (13.79) | ||

| Both male and female | 66 (29.07) | 33 (14.53) | 11 (4.84) | 66 (29.07) | 23 (10.13) | 28 (12.33) | ||

| Children with chronic diseases? | Yes | 2 (6.66) | 6 (20) | 1 (3.33) | 13 (43.33) | 1 (3.33) | 7 (23.33) | 0.040 * |

| No | 127 (29.26) | 59 (13.59) | 29 (6.68) | 115 (26.49) | 39 (8.98) | 65 (14.97) | ||

| Parental Behavior, Immunization and Precautionary Measures Related to COVID-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant’s Response | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

| Have you ever heard about or seen the campaign against COVID-19 vaccination (anti-vaccination movements)? | Yes | 222 | 47.8 |

| No | 242 | 52.2 | |

| Describe your family’s commitment to the precautionary measures against the COVID-19? | No commitment | 10 | 2.2 |

| Little commitment | 47 | 10.1 | |

| Somewhat commitment | 180 | 38.8 | |

| Much committed | 128 | 27.6 | |

| Great deal of commitment | 99 | 21.3 | |

| Did anyone within your direct family get infected with COVID-19? | Yes | 284 | 61.2 |

| No | 180 | 38.8 | |

| How severe were the symptoms of the infected person(s)? | Very mild/asymptomatic | 15 | 3.2 |

| Mild | 46 | 9.9 | |

| Moderate | 159 | 34.3 | |

| Severe | 43 | 9.3 | |

| Very severe | 17 | 3.7 | |

| Death | 4 | 0.9 | |

| No COVID-19 infection | 180 | 38.8 | |

| As a parent did you take the COVID-19 vaccine? | Yes | 445 | 95.9 |

| No | 19 | 4.1 | |

| Did you have any adverse reactions after vaccination? | Mild | 145 | 31.3 |

| Moderate | 106 | 22.8 | |

| Severe | 55 | 11.9 | |

| No | 158 | 34.1 | |

| Child/Children’s immunization history | |||

| Have you vaccinated your child with mandatory childhood vaccines? | Yes | 374 | 80.6 |

| No | 90 | 19.4 | |

| Adverse reactions after vaccination in child? | Mild | 158 | 34.1 |

| Moderate | 95 | 20.5 | |

| Severe | 41 | 8.8 | |

| No | 170 | 36.6 | |

| Driver | Responses | Intention to Vaccinate Child against COVID-19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | Yes | Delay | Undecided | No | p Value | ||

| I am concerned about serious adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccine. | Strongly agree | 141 (30.38) | 23(16.31) | 10 (7.09) | 39 (27.65) | 69 (48.93) | <0.001 * |

| Agree | 227 (48.92) | 56 (24.66) | 61 (26.87) | 78 (34.36) | 32 (14.09) | ||

| Disagree | 83 (17.88) | 41 (49.39) | 23 (27.71) | 11 (13.25) | 8 (9.63) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 13 (2.8) | 9 (69.23) | 1 (7.69) | Zero | 3 (23.07) | ||

| My child/children do or don’t need vaccines for diseases that are not common anymore. | Strongly agree | 70 (15.08) | 11 (15.71) | 10 (14.28) | 14 (20) | 35 (50) | <0.001 * |

| Agree | 150 (32.32) | 28 (18.66) | 23 (15.33) | 49 (32.66) | 50 (33.33) | ||

| Disagree | 181 (39) | 57 (31.49) | 48 (26.51) | 57 (31.49) | 19 (10.49) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 63 (13.57) | 33 (52.38) | 14 (22.22) | 8 (12.69) | 8 (12.69) | ||

| New vaccines (like COVID-19) carry more risks than older vaccines. | Strongly agree | 97 (20.9) | 7 (7.21) | 10 (10.3) | 26 (26.8) | 54 (55.67) | <0.001 * |

| Agree | 160 (34.48) | 41 (25.62) | 30 (18.75) | 51 (31.87) | 38 (23.75) | ||

| Disagree | 182 (39.22) | 70 (38.46) | 53 (29.12) | 44 (24.17) | 15 (8.24) | ||

| Strongly disagree | 25 (5.38) | 11 (44) | 2 (8) | 7 (28) | 5 (20) | ||

| Describe your family’s commitment to the precautionary measures against the COVID-19? | No commitment | 10 (2.15) | 4 (40) | 2 (20) | Zero | 4 (40) | <0.001 * |

| little commitment | 47 (10.12) | 13 (27.65) | 3 (6.38) | 20 (42.55) | 11 (23.4) | ||

| Somewhat commitment | 180 (38.79) | 36 (20) | 51 (28.33) | 55 (30.55) | 38 (21.11) | ||

| Much committed | 128 (27.58) | 37 (28.9) | 29 (22.65) | 38 (29.68) | 24 (18.75) | ||

| Great deal of commitment | 99 (21.33) | 39 (39.39) | 10 (10.1) | 15 (15.15) | 35 (35.35) | ||

| Did anyone within your direct family get infected with COVID-19? | Yes | 284 (61.2) | 63 (22.18) | 61 (21.47) | 81 (28.52) | 79 (27.81) | 0.005 * |

| No | 180 (38.79) | 66 (36.66) | 34 (18.88) | 47 (26.11) | 33 (18.33) | ||

| How severe were the symptoms of the infected person(s)? | Very mild | 15 (3.23) | 3 (20) | 2 (13.33) | 4 (26.66) | 6 (40) | 0.032 * |

| Mild | 46 (9.91) | 12 (26.08) | 9 (19.56) | 11 (23.91) | 14 (30.43) | ||

| Moderate | 159 (34.26) | 39 (24.52) | 37 (23.27) | 44 (27.67) | 39 (24.52) | ||

| Severe | 43 (9.26) | 8 (18.6) | 8 (18.6) | 12 (27.9) | 15 (34.88) | ||

| Very severe | 17 (3.66) | 1 (5.88) | 5 (29.41) | 6 (35.29) | 5 (29.41) | ||

| Death | 4 (0.86) | Zero | Zero | 4 (100) | Zero | ||

| No COVID-19 infection | 180 (38.79) | 66 (36.66) | 34 (18.88) | 47 (26.11) | 33 (18.33) | ||

| As a parent did you take the COVID-19 vaccine? | Yes | 445 (95.9) | 129 (28.98) | 90 (20.22) | 125 (28.08) | 101 (22.69) | 0.001 * |

| No | 19 (4.09) | Zero | 5 (26.31) | 3 (15.78) | 11 (57.89) | ||

| Did you have any adverse reactions after vaccination? | Mild | 145 (31.25) | 41 (28.27) | 39 (26.89) | 42 (28.96) | 23 (15.86) | <0.001 * |

| Moderate | 106 (22.84) | 31 (29.24) | 21 (19.81) | 29 (27.35) | 25 (23.58) | ||

| Severe | 55 (11.85) | 7 (12.72) | 5 (9.09) | 15 (27.27) | 28 (50.9) | ||

| No | 158 (34.05) | 50 (31.64) | 30 (18.98) | 42 (26.58) | 36 (22.78) | ||

| Have you vaccinated your child with mandatory childhood vaccines? | Yes | 374 (80.6) | 111 (29.67) | 80 (21.39) | 100 (26.73) | 83 (22.19) | 0.080 |

| No | 90 (19.39) | 18 (20) | 15 (16.66) | 28 (31.11) | 29 (32.22) | ||

| Independent Variables | Variable Coefficient(B) | p-Value | OR (95% CI)Adjusted * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Vaccine Hesitancy against COVID-19 (YES) | |||

| Age | |||

| 25 years and below | −0.782 | 0.337 | 0.457 (0.092–2.262) |

| 26 to 40 years | 0.773 | 0.014 * | 2.165 (1.167–4.019) |

| 41 years and above | - | - | 1.00 |

| Parent Working as Healthcare Professional | |||

| Yes | −0.993 | 0.007 * | 0.370 (0.181–0.758) |

| No | - | - | 1.00 |

| Job sector | |||

| Government | −1.693 | 0.058 | 0.184 (0.032–1.059) |

| Private | −0.896 | 0.344 | 0.408 (0.064–2.606) |

| Self employed | −3.633 | 0.040 * | 0.026 (0.001–0.844) |

| Unemployed | −1.224 | 0.244 | 0.294 (0.038–2.303) |

| Retired | 17.565 | 0.998 | 0.354 (0.0562–2.135) |

| Housewife | −2.423 | 0.011 * | 0.089 (0.014–0.578) |

| Student | - | - | 1.00 |

| Children suffering from chronic disease | |||

| Yes | 2.295 | 0.007 * | 9.922 (1.895–51.939) |

| No | - | - | 1.00 |

| Family’s commitment to follow COVID-19 precautionary measure | |||

| No commitment | −0.577 | 0.525 | 0.562 (0.095–3.326) |

| Little commitment | 0.690 | 0.181 | 1.993 (0.726–5.470) |

| Somewhat commitment | 1.295 | <0.001 * | 3.653 (1.781–7.492) |

| Much committed | 0.970 | 0.008 * | 2.637 (1.284–5.417) |

| Great deal of commitment | - | - | 1.00 |

| COVID-19 infected person in family | |||

| Yes | 0.531 | 0.048 * | 1.701 (0.989–2.926) |

| No | - | - | 1.00 |

| Mandatory childhood Immunization | |||

| Yes | −0.899 | 0.011 * | 0.407 (0.204–0.813) |

| No | - | - | 1.00 |

| Vaccine Hesitancy score (VHS) | |||

| Hesitant VHS score < 3 points | 2.254 | <0.001 * | 9.529 (5.972–15.204) |

| Not Hesitant: VHS score ≥ 3 points | - | - | 1.00 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aedh, A.I. Parents’Attitudes, Their Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and the Contributing Factors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081264

Aedh AI. Parents’Attitudes, Their Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and the Contributing Factors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines. 2022; 10(8):1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081264

Chicago/Turabian StyleAedh, Abdullah Ibrahim. 2022. "Parents’Attitudes, Their Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and the Contributing Factors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey" Vaccines 10, no. 8: 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081264

APA StyleAedh, A. I. (2022). Parents’Attitudes, Their Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccines for Children and the Contributing Factors in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines, 10(8), 1264. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081264