A Framework for Inspiring COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in African American and Latino Communities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Where to Start: Start with Community-Based Organizations

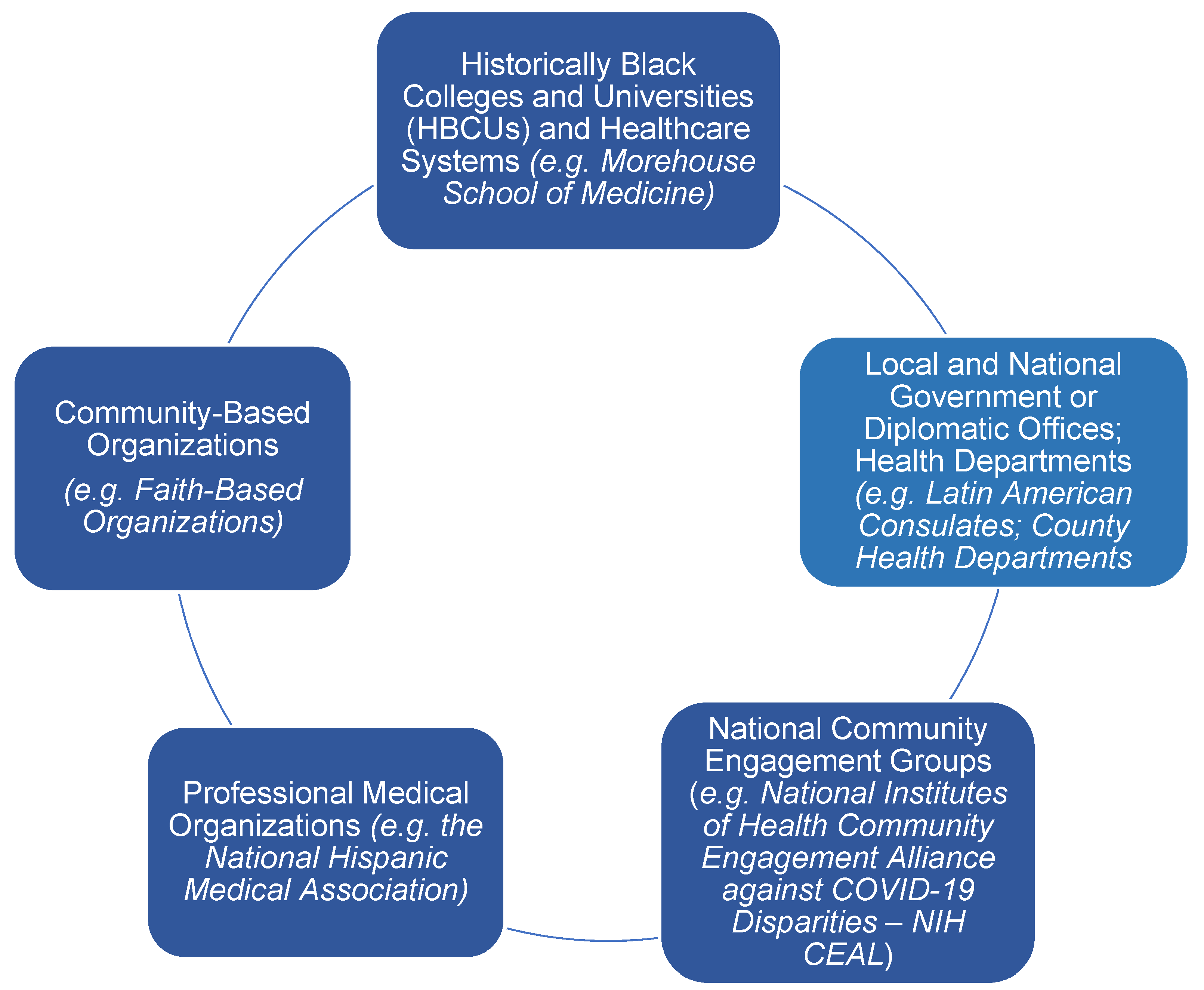

3. Key Community Partnerships

4. Other Key Partners

4.1. Local Health Departments

4.2. Local and National Governments or Diplomatic Offices

4.3. National Community Engagement Groups

4.4. Professional Medical Organizations

4.5. Historically Black Colleges, Universities, and Academic Health Systems

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: COVID-19 COVID-19 Weekly Cases and Deaths per 100,000 Population by Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Sex. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographicsovertime (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Magesh, S.; John, D.; Li, W.T.; Li, Y.; Mattingly-App, A.; Jain, S.; Chang, E.Y.; Ongkeko, W.M. Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes by Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status: A Systematic-Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, K.; Ayers, C.K.; Kondo, K.K.; Saha, S.; Advani, S.M.; Young, S.; Spencer, H.; Rusek, M.; Anderson, J.; Veazie, S.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in COVID-19-Related Infections, Hospitalizations, and Deaths: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, Z.; Ross-Driscoll, K.; Wang, Z.; Smothers, L.; Mehta, A.K.; Patzer, R.E. Racial and Ethnic Differences and Clinical Outcomes of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Presenting to the Emergency Department. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullar, R.; Marcelin, J.R.; Swartz, T.H.; Piggott, D.A.; Macias Gil, R.; Mathew, T.A.; Tan, T. Racial Disparity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in African American Communities. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 890–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias Gil, R.; Marcelin, J.R.; Zuniga-Blanco, B.; Marquez, C.; Mathew, T.; Piggott, D.A. COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparate Health Impact on the Hispanic/Latinx Population in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 1592–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price-Haywood, E.G.; Burton, J.; Fort, D.; Seoane, L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Demographic Trends of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US Reported to CDC. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographics (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Thompson, H.S.; Manning, M.; Mitchell, J.; Kim, S.; Harper, F.W.K.; Cresswell, S.; Johns, K.; Pal, S.; Dowe, B.; Tariq, M.; et al. Factors Associated With Racial/Ethnic Group-Based Medical Mistrust and Perspectives on COVID-19 Vaccine Trial Participation and Vaccine Uptake in the U.S. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricorian, K.; Turner, K. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wailoo, K. Historical Aspects of Race and Medicine: The Case of J. Marion Sims. JAMA 2018, 320, 1529–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J. Historical Origins of the Tuskegee Experiment: The Dilemma of Public Health in the United States. Uisahak 2017, 26, 545–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, D. Differential occupational risk for COVID-19 and other infection exposure according to race and ethnicity. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2020, 63, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, C.J.; Aristega Almeida, B.; Corpuz, G.S.; Mora, H.A.; Aladesuru, O.; Shapiro, M.F.; Sterling, M.R. Challenges with social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic among Hispanics in New York City: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Diaz, C.E.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Mena, L.; Hall, E.; Honermann, B.; Crowley, J.S.; Baral, S.; Prado, G.J.; Marzan-Rodriguez, M.; Beyrer, C.; et al. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: Examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 52, 46–53.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abba-Aji, M.; Stuckler, D.; Galea, S.; McKee, M. Ethnic/racial minorities’ and migrants’ access to COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators. J. Migr. Health 2022, 5, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletly, C.L.; Lechuga, J.; Dickson-Gomez, J.B.; Glasman, L.R.; McAuliffe, T.L.; Espinoza-Madrigal, I. Assessment of COVID-19-Related Immigration Concerns Among Latinx Immigrants in the U.S. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2117049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugenyi, L.; Mijumbi, A.; Nanfuka, M.; Agaba, C.; Kaliba, F.; Semakula, I.S.; Nazziwa, W.B.; Ochieng, J. Capacity of community advisory boards for effective engagement in clinical research: A mixed methods study. BMC Med. Ethics 2021, 22, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, P.; McNabb, P.; Maddali, S.R.; Heath, J.; Santibañez, S. Engaging Communities to Reach Immigrant and Minority Populations: The Minnesota Immunization Networking Initiative (MINI), 2006–2017. Public Health Rep. 2019, 134, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richman, A.R.; Torres, E.; Wu, Q.; Kampschroeder, A.P. Evaluating a Community-Based Breast Cancer Prevention Program for Rural Underserved Latina and Black Women. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Latino Community Fund Georgia. Available online: https://lcfgeorgia.org (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Unidos Georgia. Available online: https://www.unidosgeorgia.com (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Derose, K.P.; Williams, M.V.; Branch, C.A.; Flórez, K.R.; Hawes-Dawson, J.; Mata, M.A.; Oden, C.W.; Wong, E.C. A Community-Partnered Approach to Developing Church-Based Interventions to Reduce Health Disparities Among African-Americans and Latinos. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibañez, S.; Ottewell, A.; Harper-Hardy, P.; Ryan, E.; Christensen, H.; Smith, N. A Rapid Survey of State and Territorial Public Health Partnerships With Faith-Based Organizations to Promote COVID-19 Vaccination. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, C. Fostering Healthy Communities @ Hair Care Centers. ABNF J. 2000, 11, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.; Porter, A., 3rd; Biddle, J.; Balamurugan, A.; Smith, M.R. The Arkansas Minority Barber and Beauty Shop Health Initiative: Meeting People Where They Are. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, R.G.; Ravenell, J.E.; Freeman, A.; Leonard, D.; Bhat, D.G.; Shafiq, M.; Knowles, P.; Storm, J.S.; Adhikari, E.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; et al. Effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men: The BARBER-1 study: A cluster randomized trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momplaisir, F.; Haynes, N.; Nkwihoreze, H.; Nelson, M.; Werner, R.M.; Jemmott, J. Understanding Drivers of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Blacks. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1784–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.; Haynes, N.; Momplaisir, F. Partnering With Barbershops and Salons to Engage Vulnerable Communities During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlanta Science Festival Begins Saturday with Talk on COVID Vaccines in Black Communities (SaportaReport). Available online: https://saportareport.com/atlanta-science-festival-begins-saturday-with-talk-on-covid-vaccine-in-black-communities/sections/reports/david/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Saint Louis Story Stitchers. Available online: https://storystitchers.org/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Story Stitchers Use Art to Address COVID. Vaccine Hesitancy: Using Lyrics and Famous Quotes, a St. Louis Program Is Urging Young Black People to Get Vaccinated against COVID-19. Available online: https://sacobserver.com/2022/03/story-stitchers-use-art-to-address-covid-vaccine-hesitancy/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- NCDHHS to Promote COVID-19 Vaccination at Mexico vs. Ecuador Soccer Match NCDHHS Promoverá la Vacunación Contra el COVID-19 en el Partido de Fútbol Amistoso entre México y Ecuador. Available online: https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2021/10/22/ncdhhs-promote-covid-19-vaccination-mexico-vs-ecuador-soccer-match (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Demeke, J.; McFadden, S.M.; Dada, D.; Djiometio, J.N.; Vlahov, D.; Wilton, L.; Wang, M.; Nelson, L.E. Strategies that Promote Equity in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake for Undocumented Immigrants: A Review. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deal, A.; Hayward, S.E.; Huda, M.; Knights, F.; Crawshaw, A.F.; Carter, J.; Hassan, O.B.; Farah, Y.; Ciftci, Y.; Rowland-Pomp, M.; et al. Strategies and action points to ensure equitable uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations: A national qualitative interview study to explore the views of undocumented migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. J. Migr. Health 2021, 4, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- City of St. Louis Department of Health to Host Pediatric Vaccine Virtual Town Hall. Available online: https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/health/news/pediatric-vaccine-town-hall-discussion.cfm (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Ventanilla de Salud. Available online: https://ventanilladesalud.org/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- National Institutes of Health Community Engagement Alliance against COVID-19 Disparities. Available online: https://covid19community.nih.gov/ (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- National Institutes of Health Community Engagement Alliance-Vaccines. Available online: https://covid19community.nih.gov/resources/learning-about-vaccines (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- National Medical Association—About Us. Available online: https://www.nmanet.org/page/About_Us (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- National Medical Association National Program Overview. Available online: https://www.nmanet.org/page/NatProgOverview (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- National Medical Association COVID-19 Task Force on Vaccines and Therapeutics. Available online: https://www.nmanet.org/news/544970/NMA-COVID-19-Task-Force-on-Vaccines-and-Therapeutics.htm (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- Atlanta Medical Association Ask a Black Doctor. Available online: https://atlmed.org/askablackdoctor/ (accessed on 11 June 2022).

- National Hispanic Medical Association. Available online: https://www.nhmamd.org/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Vaccinate for All 2022 Action Plan. Available online: https://www.vaccinateforall.org/resources (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- National Pan-Hellenic Council. Available online: https://nphchq.com/millennium1/about/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- CDC Foundation—Mobilizing Sisterhood to Fight COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cdcfoundation.org/stories/mobilizing-sisterhood-fight-covid-19-divine-nine-sororities (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- AKAs Observe National HBCU Week with Free COVID Vaccines, Tests, Mammograms. Available online: https://afro.com/akas-observe-national-hbcu-week-with-free-covid-vaccines-test-mammograms/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Morehouse School of Medicine Mobile Vaccination Unit. Available online: https://www.msm.edu/news-center/coronavirusadvisory/msmmobilevaccinations.php (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Alcendor, D.J.; Juarez, P.D.; Matthews-Juarez, P.; Simon, S.; Nash, C.; Lewis, K.; Smoot, D. Meharry Medical College Mobile Vaccination Program: Implications for Increasing COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among Minority Communities in Middle Tennessee. Vaccines 2022, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marco, M.; Kearney, W.; Smith, T.; Jones, C.; Kearney-Powell, A.; Ammerman, A. Growing partners: Building a community-academic partnership to address health disparities in rural North Carolina. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2014, 8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, S.M.; Demeke, J.; Dada, D.; Wilton, L.; Wang, M.; Vlahov, D.; Nelson, L.E. Confidence and Hesitancy During the Early Roll-out of COVID-19 Vaccines among Black, Hispanic, and Undocumented Immigrant Communities: A Review. J. Urban Health 2022, 99, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M.; Rainie, L.; Budiman, A. Financial and Health Impacts of COVID-19 Vary Widely by Race and Ethnicity. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/05/financial-and-health-impacts-of-covid-19-vary-widely-by-race-and-ethnicity/ (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Marcelin, J.R.; Swartz, T.H.; Bernice, F.; Berthaud, V.; Christian, R.; Da Costa, C.; Fadul, N.; Floris-Moore, M.; Hlatshwayo, M.; Johansson, P.; et al. Addressing and Inspiring Vaccine Confidence in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wiley, Z.; Khalil, L.; Lewis, K.; Lee, M.; Leary, M.; Cantos, V.D.; Ofotokun, I.; Rouphael, N.; Rebolledo, P.A. A Framework for Inspiring COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in African American and Latino Communities. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081319

Wiley Z, Khalil L, Lewis K, Lee M, Leary M, Cantos VD, Ofotokun I, Rouphael N, Rebolledo PA. A Framework for Inspiring COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in African American and Latino Communities. Vaccines. 2022; 10(8):1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081319

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiley, Zanthia, Lana Khalil, Kennedy Lewis, Matthew Lee, Maranda Leary, Valeria D. Cantos, Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Nadine Rouphael, and Paulina A. Rebolledo. 2022. "A Framework for Inspiring COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in African American and Latino Communities" Vaccines 10, no. 8: 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081319

APA StyleWiley, Z., Khalil, L., Lewis, K., Lee, M., Leary, M., Cantos, V. D., Ofotokun, I., Rouphael, N., & Rebolledo, P. A. (2022). A Framework for Inspiring COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence in African American and Latino Communities. Vaccines, 10(8), 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081319