Vaccine Uptake and COVID-19 Frequency in Pregnant Syrian Immigrant Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Evaluation and Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Vaccines and Immunization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/vaccines-and-immunization#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccines and Immunizations. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/index.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pregnancy and Vaccination. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pregnancy/vacc-during-after.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- CDC Statement on Pregnancy Health Advisory. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0929-pregnancy-health-advisory.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine Safety. Questions and Concerns. Vaccines During Pregnancy FAQs. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/vaccines-during-pregnancy.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- T.C. Ministry of Health, General Directorate of Public Health, Department of Women’s and Reproductive Health. Antenatal Care Management Guidelines (2018). (Publication No: 925). Available online: https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/depo/birimler/Kadin_ve_Ureme_Sagligi_Db/dokumanlar/rehbler/dogum_oncesi_bakim_2020.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- T.C. Ministry of Health, General Directorate of Public Health. Adult Vaccination: Adult Vaccination Practices in Turkey. Available online: https://asi.saglik.gov.tr/asi-kimlere-yapilir/liste/30-yeti%C5%9Fkina%C5%9F%C4%B1lama.html (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). COVID-19 during Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/special-populations/pregnancy-data-on-covid-19/what-cdc-is-doing.html (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 Vaccination Considerations for Obstetric-Gynecologic Care. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/vaccinating-pregnant-and-lactating-patients-against-covid-19 (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Guidance Coronavirus (COVID-19), Pregnancy and Women’s Health. Vaccination. COVID-19 Vaccines, Pregnancy and Breastfeeding FAQs. Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-pregnancy-and-women-s-health/vaccination/covid-19-vaccines-pregnancy-and-breastfeeding-faqs/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Elgendy, M.O.; El-Gendy, A.O.; Mahmoud, S.; Mohammed, T.Y.; Abdelrahim, M.E.A.; Sayed, A.M. Side effects and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines among the Egyptian population. Vaccines 2022, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Xu, P.; Ye, Q. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccines: Types, thoughts, and application. J Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e23937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Sivajohan, B.; McClymont, E.; Albert, A.; Elwood, C.; Ogilvie, G.; Money, D. Systematic review of the safety, immunogenicity, and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant and lactating individuals and their infants. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 156, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahara, A.; Biggio, J.R.; Elmayan, A.; Williams, F.B. Safety-related outcomes of novel mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 39, 1484–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SeyedAlinaghi, S.A.; MohsseniPour, M.; Saeidi, S.; Habibi, P.; Dashti, M.; Nazarian, N.; Noori, T.; Pashaei, Z.; Bagheri, A.; Ghasemzadeh, A.; et al. Complications of COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy; a systematic review. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2022, 10, e76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, A.; Alamer, E.; Daws, D.; Hakami, M.; Darraj, M.; Abdelwahab, S.; Maghfuri, A.; Algaissi, A. Evaluation of side effects associated with COVID-19 vaccines in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2021, 9, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasa, J.; Holmberg, V.; Sainio, S.; Kankkunen, P.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. Maternal health care utilization and the obstetric outcomes of undocumented women in Finland—A retrospective register-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V. Intercultural communication in foreign subsidiaries: The influence of expatriates’ language and cultural competencies. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushulak, B.D.; Weekers, J.; MacPherson, D.W. Migrants and emerging public health issues in a globalized world: Threats, risks and challenges, an evidence-based framework. Emerg. Health Threats J. 2009, 2, 7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Ensuring the Integration of Refugees and Migrants in Immunization Policies, Planning and Service Delivery Globally; Global Evidence Reviewon Health and Migration (GEHM) Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Führer, A.; Pacolli, L.; Yilmaz-Aslan, Y.; Brzoska, P. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Its Determinants among Migrants in Germany—Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Kaitelidou, D. Uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descamps, A.; Launay, O.; Bonnet, C.; Blondel, B. Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake and vaccine refusal among pregnant women in France: Results from a national survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mipatrini, D.; Balcılar, M.; Dembech, M.; Ergüder, T.; Ursu, P. Survey on the Health Status, Services Utilization and Determinants of Health: Syrian Refugee Population in Turkey; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matlin, S.A.; Smith, A.C.; Merone, J.; LeVoy, M.; Shah, J.; Vanbiervliet, F.; Vandentorren, S.; Vearey, J.; Saso, L. The challenge of reaching undocumented migrants with COVID-19 vaccination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, M.B.; Wood, R.A.; Cooke, S.K.; Sampson, H.A. Egg hypersensitivity and adverse reactions to measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. J. Pediatr. 1992, 120, 878–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caubet, J.-C.; Wang, J. Current understanding of egg allergy. Pediatr. Clin. 2011, 58, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Socio-Economic Development Ranking Research of Districts. SEGE-2022, Ankara. Available online: https://www.sanayi.gov.tr/merkez-birimi/b94224510b7b/sege/ilce-sege-raporlari (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- World Health Organization. Protecting All against Tetanus: Guide to Sustaining Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination (MNTE) and Broadening Tetanus Protection for All Populations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe, H.; Lawn, J.; Vandelaer, J.; Roper, M.; Cousens, S. Tetanus toxoid immunization to reduce mortality from neonatal tetanus. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 39, i102–i109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- T.C. Ministry of Health COVID-19 Vaccine Information Platform. Available online: https://covid19asi.saglik.gov.tr/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Vaccination Status of Immigrants in Turkey: III Survey Results Community-Based Migration Programs Health and Psychosocial Support Program Turkey, November 2021. Available online: https://toplummerkezi.kizilay.org.tr/kutuphane/raporlar (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Ransing, R.; Raghuvee, P.; Mhamunkar, A.; Kukreti, P.; Puri, M.; Patil, S.; Pavithra, H.; Padma, K.; Kumar, P.; Ananthathirtha, K.; et al. The COVID-19 vaccine confidence project for perinatal women (CCPP)—Development of a stepped-care model to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in low and middle-income countries. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransing, R.; Kukreti, P.; Raghuveer, P.; Puri, M.; Paranjape, A.D.; Patil, S.; Hegade, P.; Padma, K.; Kumar, P.; Kishore, J.; et al. A brief psycho-social intervention for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among perinatal women in low-and middle-income countries: Need of the hour. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2022, 67, 102929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İkiışık, H.; Sezerol, M.A.; Taşçı, Y.; Maral, I. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A community-based research in Turkey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Perera, S.M.; Garbern, S.C.; Diwan, E.A.; Othman, A.; Ali, J.; Awada, N. Variations in COVID-19 vaccine attitudes and acceptance among refugees and Lebanese nationals pre-and post-vaccine rollout in Lebanon. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirrow, H.; Barnett, S.; Bell, S.; Riaposova, L.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Kampmann, B.; Holder, B. Women’s views on accepting COVID-19 vaccination during and after pregnancy, and for their babies: A multi-methods study in the UK. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeway, H.; Prasad, S.; Kalafat, E.; Heath, P.T.; Ladhani, S.N.; Le Doare, K.; Magee, L.A.; O’brien, P.; Rezvani, A.; von Dadelszen, P.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: Coverage and safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 236.e1–236.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lier, A.; Steens, A.; Ferreira, J.A.; van der Maas, N.A.; de Melker, H.E. Acceptance of vaccination during pregnancy: Experience with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) in the Netherlands. Vaccine 2012, 30, 2892–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezerol, M.A.; Davun, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Related Factors among Unvaccinated Pregnant Women during the Pandemic Period in Turkey. Vaccines 2023, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Santos, N.A.; Hamer, G.L.; Garrido-Lozada, E.G.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.A. SARS-CoV-2 Infections in a High-Risk Migratory Population Arriving to a Migrant House along the US-Mexico Border. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassa, M.; Yirmibes, C.; Cavusoglu, G.; Eksi, H.; Dogu, C.; Usta, C.; Mutlu, M.; Birol, P.; Gulumser, C.; Tug, N. Outcomes of universal SARS-CoV-2 testing program in pregnant women admitted to hospital and the adjuvant role of lung ultrasound in screening: A prospective cohort study. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 3820–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gea-Sánchez, M.; Alconada-Romero, Á.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Pastells, R.; Gastaldo, D.; Molina, F. Undocumented immi grant women in Spain: A scoping review on access to and utilization of health and social services. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T.P.; Pallerla, S.R.; Rüter, J.; Augustin, Y.; Kremsner, P.G.; Krishna, S.; Meyer, C.G. Host genetic factors determining COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. EBioMedicine 2021, 72, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, A.; Mehendale, M.; AlRawashdeh, M.M.; Sestacovschi, C.; Sharath, M.; Pandav, K.; Marzban, S. The association of COVID-19 severity and susceptibility and genetic risk factors: A systematic review of the literature. Gene 2022, 20, 146674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, S.J.; Carruthers, J.; Calvert, C.; Denny, C.; Donaghy, J.; Goulding, A.; Hopcroft, L.E.; Hopkins, L.; McLaughlin, T.; Pan, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, C.Y.S.; Tarrant, M. Determinants of uptake of influenza vaccination among pregnant women—A systematic review. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4602–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sel, G.; Balcı, S.; Aynalı, B.; Navruzova, K.; Akdemir, A.Y.; Harma, M.; Harma, M. Gebelerin grip aşısı yaptırmama nedenleri üzerine kesitsel çalışma. STED 2020, 29, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, G.; Erdoğan, N. Gebelerin mevsimsel influenza aşısı ile ilgili bilgi, tutum ve davranışları. Anatol. Clin. 2020, 25, 258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Balcilar, M.; Gulcan, C. Determinants of Protective Healthcare Services Awareness among Female Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Zuanna, T.; Del Manso, M.; Giambi, C.; Riccardo, F.; Bella, A.; Caporali, M.G.; Dente, M.G.; Declich, S. Immunization offer targeting migrants: Policies and practices in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ekezie, W.; Awwad, S.; Krauchenberg, A.; Karara, N.; Dembiński, Ł.; Grossman, Z.; del Torso, S.; Dornbusch, H.J.; Neves, A.; Copley, S.; et al. Access to Vaccination among Disadvantaged, Isolated and Difficult-to-Reach Communities in the WHO European Region: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (min-max) | 25.0 (18.0–46.0) |

| Trimester, n (%) | |

| First | 171 (41.9) |

| Second | 194 (47.6) |

| Third | 43 (10.5) |

| Number of pregnancies, median (min-max) | 3.0 (1–10) |

| High-risk pregnancy, n (%) | 36 (8.8) |

| Influenza vaccination | n (%) |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| No | 408 (100.0) |

| Tetanus vaccination (at least 2 doses) | n (%) |

| Yes | 77 (29.7) |

| No | 182 (70.3) |

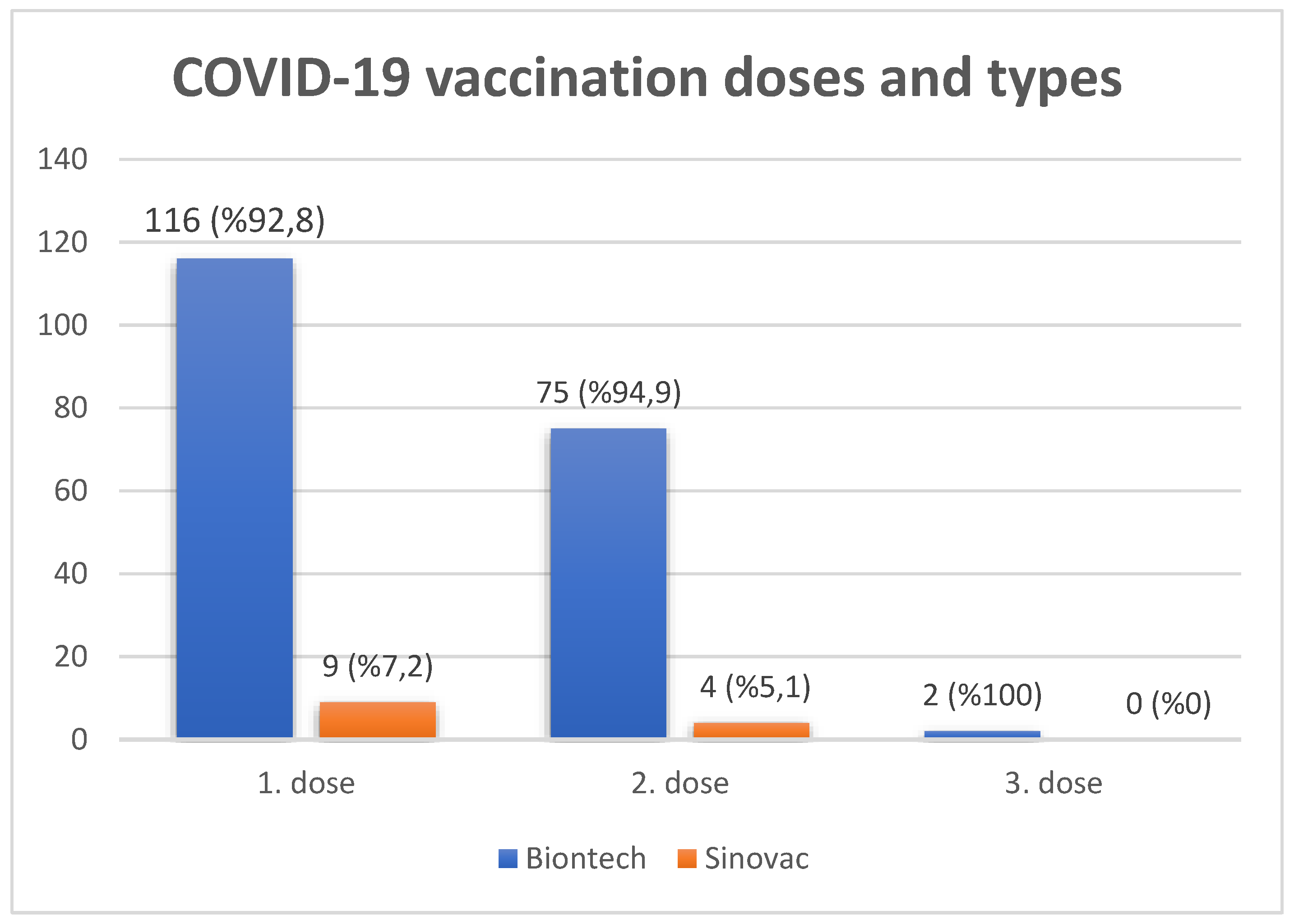

| COVID-19 vaccination (at least 2 doses) | n (%) |

| Yes | 79 (19.4) |

| Two doses | 77 (18.9) |

| Three doses | 2 (0.5) |

| No | 329 (80.6) |

| No vaccine | 283 (69.3) |

| Single dose | 46 (11.3) |

| History of COVID-19 infection | n (%) |

| Yes | 17 (4.2) |

| No | 391 (95.8) |

| COVID-19 PCR-positive pregnant women | n (%) |

| Trimester | |

| First | 2 (11.8) |

| Second | 4 (23.5) |

| Third | 11 (64.7) |

| COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake | |||

| No | Yes | p Value | |

| Median (Min-Max) | Median (Min-Max) | ||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Age | 25.0 (18.0–46.0) | 27.0 (18.0–41.0) | 0.097 * |

| 26.08 ± 5.96 | 27.09 ± 5.60 | ||

| Number of pregnancies | 3.0 (1.0–9.0) | 3.0 (1.0–10.0) | 0.007 * |

| 2.99 ± 1.55 | 3.73 ± 2.10 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | p value | |

| Trimester | 0.013 ** | ||

| First | 127 (74.3) | 44 (25.7) | |

| Second | 163 (84.0) | 31 (16.0) | |

| Third | 39 (90.7) | 4 (9.3) | |

| High-risk pregnancy | 0.634 ** | ||

| Yes | 8 (77.8) | 8 (22.2) | |

| No | 274 (81.1) | 64 (18.9) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sezerol, M.A.; Altaş, Z.M. Vaccine Uptake and COVID-19 Frequency in Pregnant Syrian Immigrant Women. Vaccines 2023, 11, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020257

Sezerol MA, Altaş ZM. Vaccine Uptake and COVID-19 Frequency in Pregnant Syrian Immigrant Women. Vaccines. 2023; 11(2):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020257

Chicago/Turabian StyleSezerol, Mehmet Akif, and Zeynep Meva Altaş. 2023. "Vaccine Uptake and COVID-19 Frequency in Pregnant Syrian Immigrant Women" Vaccines 11, no. 2: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020257

APA StyleSezerol, M. A., & Altaş, Z. M. (2023). Vaccine Uptake and COVID-19 Frequency in Pregnant Syrian Immigrant Women. Vaccines, 11(2), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020257