Prevalence and Motivators of Getting a COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Canada: Results from the iCARE Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants and Recruitment

2.3. iCARE Survey Questionnaire

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Sociodemographic Differences as a Function of Booster Vaccination Status

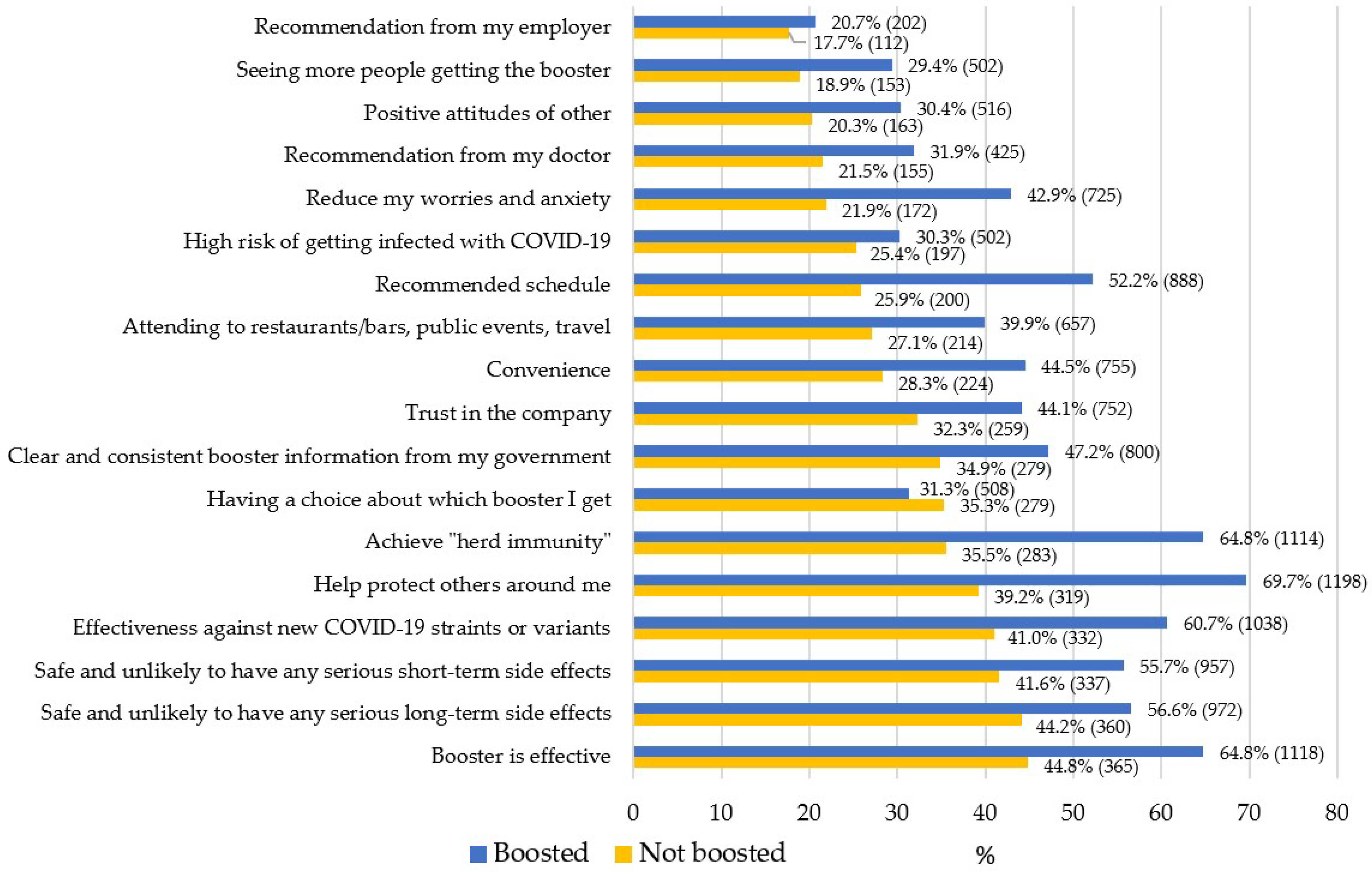

3.3. Motivators for Getting the COVID-19 Booster Vaccine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- West, R.; Michie, S.; Rubin, G.J.; Amlôt, R. Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. COVID-19: Effectiveness and Benefits of Vaccination. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/vaccines/effectiveness-benefits-vaccination.html (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- WHO. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization Updates Recommendations on Boosters, COVID-19 Vaccines for Children—PAHO/WHO | Pan American Health Organization (n.d.). Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/21-1-2022-who-strategic-advisory-group-experts-immunization-updates-recommendations-boosters (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Levine-Tiefenbrun, M.; Yelin, I.; Alapi, H.; Herzel, E.; Kuint, J.; Chodick, G.; Gazit, S.; Patalon, T.; Kishony, R. Waning of SARS-CoV-2 booster viral-load reduction effectiveness. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Coppeta, L.; Ferrari, C.; Somma, G.; Mazza, A.; D’Ancona, U.; Marcuccilli, F.; Grelli, S.; Aurilio, M.T.; Pietroiusti, A.; Magrini, A.; et al. Reduced Titers of Circulating Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies and Risk of COVID-19 Infection in Healthcare Workers during the Nine Months after Immunization with the BNT162b2 mRNA Vaccine. Vaccines 2022, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubet, P.; Laureillard, D.; Martin, A.; Larcher, R.; Sotto, A. Why promoting a COVID-19 vaccine booster dose? Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2021, 40, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 22 June 2022).

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, M.; Arghittu, A.; Castiglia, P. Knowledge and Behaviours towards Immunisation Programmes: Vaccine Hesitancy during the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Demographics: COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage in Canada-Canada.ca. Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/vaccination-coverage/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Al-Qerem, W.; Al Bawab, A.Q.; Hammad, A.; Ling, J.; Alasmari, F. Willingness of the Jordanian Population to Receive a COVID-19 Booster Dose: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2022, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. Predicting COVID-19 booster vaccine intentions. Appl. Psychology. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, B.M.; Keisari, S.; Palgi, Y. Vaccine and Psychological Booster: Factors Associated With Older Adults’ Compliance to the Booster COVID-19 Vaccine in Israel. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 1636–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, S.L.; Lavoie, K.L.; Boyle, J.; Stojanovic, J.; Joyal-Desmarais, K. International assessment of the link between COVID-19 related attitudes, concerns and behaviours in relation to public health policies: Optimising policy strategies to improve health, economic and quality of life outcomes (the iCARE Study). BMJ open 2021, 11, e046127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Groenewoud, R.; Rachor, G.S.; Asmundson, G.J. A Proactive Approach for Managing COVID-19: The Importance of Understanding the Motivational Roots of Vaccination Hesitancy for SARS-CoV2. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 575950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqub, O.; Castle-Clarke, S.; Sevdalis, N.; Chataway, J. Attitudes to vaccination: A critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 112, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehraeen, E.; Karimi, A.; Barzegary, A.; Vahedi, F.; Afsahi, A.M.; Dadras, O.; Moradmand-Badie, B.; Seyed Alinaghi, S.A.; Jahanfar, S. Predictors of mortality in patients with COVID-19-a systematic review. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 40, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajgain, K.T.; Badal, S.; Bajgain, B.B.; Santana, M.J. Prevalence of comorbidities among individuals with COVID-19: A rapid review of current literature. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2021, 49, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oglesby, M.E.; Schmidt, N.B. The role of threat level and intolerance of uncertainty (IU) in anxiety: An experimental test of IU theory. Behavior Therapy 2017, 48, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, F.; Lapp, L.K.; Peretti, C.S. Current research on cognitive aspects of anxiety disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2011, 24, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrell, J.; Meares, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Freeston, M. Toward a definition of intolerance of uncertainty: A review of factor analytical studies of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Clin. Psychol. Review 2011, 31, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavail, K.H.; Kennedy, A.M. The Role of Attitudes About Vaccine Safety, Efficacy, and Value in Explaining Parents’ Reported Vaccination Behavior. Health Educ. Behav. 2013, 40, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, P.G.; Shah, M.D.; Delgado, J.R.; Thomas, K.; Vizueta, N.; Cui, Y.; Vangala, S.; Shetgiri, R.; Kapteyn, A. Parents’ Intentions and Perceptions About COVID-19 Vaccination for Their Children: Results From a National Survey. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021052335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Vaccination Hesitancy among Canadian Parents. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-publique/services/publications/vie-saine/hesitation-vaccination-parents-canadiens.html (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kaur, M.; Kaur, R.; Grover, A.; Nash, D.; El-Mohandes, A. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance, Intention, and Hesitancy: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 698111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslauriers, F.; Léger, C.; Bacon, S.L.; Lavoie, K.L. International prevalence and motivators for getting COVID-19 booster vaccines: Results from the iCARE study in Australia Italy and Colombia. In Proceedings of the American Psychosomatic Society 80th Annual Scientific Meeting 2023, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 8–11 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. COVID-19 Vaccines: Everything You Need to Know. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/covid19-vaccines (accessed on 14 December 2022).

| Not Boosted | Boosted | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 859) | (N = 1744) | ||

| Descriptive characteristics variables | % (n) | % (n) | pa |

| Sex | |||

| Man | 48.9 (419) | 46.9 (813) | 0.323 |

| Woman | 51.1 (437) | 53.1 (921) | |

| Missing values | 410 | ||

| Age | |||

| Less than or equal to 25 years | 18.7 (159) | 9.5 (164) | <0.001 |

| 26–50 years | 53.4 (455) | 30.0 (522) | |

| 51 years or more | 27.9 (238) | 60.5 (1051) | |

| Missing values | 412 | ||

| Education level | |||

| High school diploma or less | 74.0 (633) | 71.1 (1231) | 0.132 |

| College or more | 26.0 (223) | 28.9 (500) | |

| Missing values | 415 | ||

| Income | |||

| Less than 60K/year | 47.6 (365) | 43.7 (682) | 0.075 |

| 60K/year or more | 52.4 (401) | 56.3 (877) | |

| Missing values | 676 | ||

| Chronic disease | |||

| No chronic disease | 63.5 (529) | 49.0 (836) | <0.001 |

| At least one chronic disease | 36.5 (304) | 51.0 (870) | |

| Missing values | 462 | ||

| Presence of any depressive disorder | |||

| Yes | 21.1 (175) | 15.9 (273) | 0.001 |

| No | 78.9 (651) | 84.1 (1448) | |

| Missing values | 454 | ||

| Presence of any anxiety disorder | |||

| Yes | 26.8 (223) | 20.3 (347) | 0.001 |

| No | 73.2 (610) | 79.7 (1363) | |

| Missing values | 458 | ||

| Parent | |||

| Not a parent | 71.7 (601) | 84.1 (1444) | <0.001 |

| Parent | 28.3 (238) | 15.9 (272) | |

| Missing values | 447 | ||

| Known or thought to have been infected with COVID-19 | |||

| Yes | 70.9 (227) | 84.8 (248) | <0.001 |

| No | 29.1 (552) | 15.2 (1383) | |

| Missing values | 591 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Léger, C.; Deslauriers, F.; Gosselin Boucher, V.; Phillips, M.; Bacon, S.L.; Lavoie, K.L. Prevalence and Motivators of Getting a COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Canada: Results from the iCARE Study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020291

Léger C, Deslauriers F, Gosselin Boucher V, Phillips M, Bacon SL, Lavoie KL. Prevalence and Motivators of Getting a COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Canada: Results from the iCARE Study. Vaccines. 2023; 11(2):291. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020291

Chicago/Turabian StyleLéger, Camille, Frédérique Deslauriers, Vincent Gosselin Boucher, Meghane Phillips, Simon L. Bacon, and Kim L. Lavoie. 2023. "Prevalence and Motivators of Getting a COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Canada: Results from the iCARE Study" Vaccines 11, no. 2: 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020291

APA StyleLéger, C., Deslauriers, F., Gosselin Boucher, V., Phillips, M., Bacon, S. L., & Lavoie, K. L. (2023). Prevalence and Motivators of Getting a COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Canada: Results from the iCARE Study. Vaccines, 11(2), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020291