Investigating the Psychological, Social, Cultural, and Religious Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention in Digital Age: A Media Dependency Theory Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

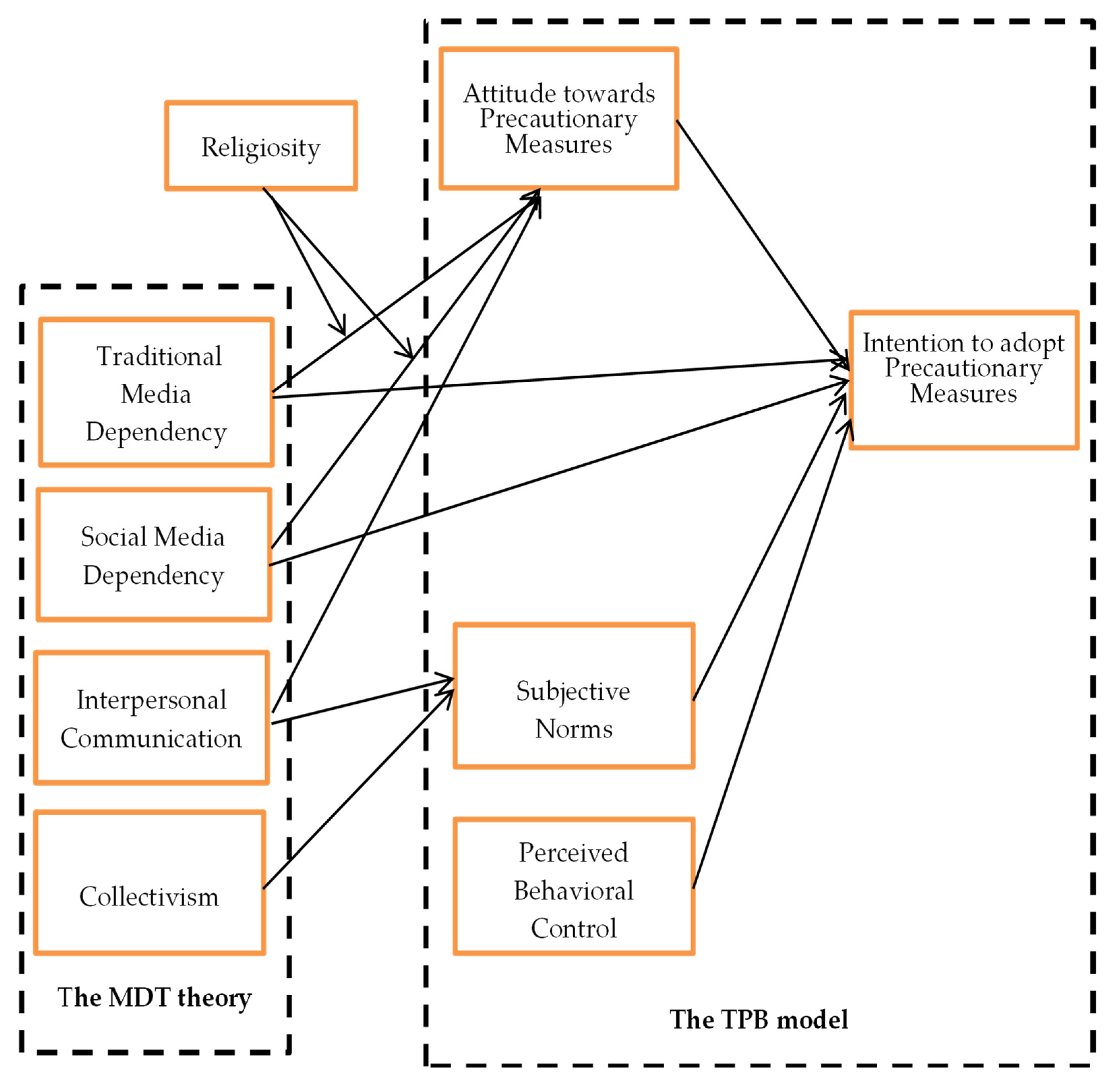

2.1. Theoretical Underpinning and Framework

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Traditional Media and Social Media Dependency

2.2.2. Interpersonal Communication and COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention

2.2.3. Collectivism

2.2.4. The Role of Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Behavioral Control

2.2.5. The Moderating Role of Religiosity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design, Participants, and Procedure

3.2. Instrumentation

3.2.1. Attitude towards Precautionary Measures

3.2.2. Subjective Norms

3.2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

3.2.4. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention

3.2.5. Media Dependency: Traditional Media and Social Media

3.2.6. Interpersonal Communication

3.2.7. Collectivism

3.2.8. Religiosity

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hua, J.; Shaw, R. Corona virus (COVID-19)“infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of china. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Hsealth 2020, 17, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, F.; Panatik, S.A.; Sarwar, F. Psychology of Preventive Behavior for COVID-19 outbreak. J. Res. Psychol. 2020, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J.; DeFleur, M.L. A dependency model of mass-media effects. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, V.-P.; Pham, T.-H.; Ho, M.-T.; Nguyen, M.-H.; P Nguyen, K.-L.; Vuong, T.-T.; Tran, T.; Khuc, Q.; Ho, M.-T.; Vuong, Q.-H. Policy response, social media and science journalism for the sustainability of the public health system amid the COVID-19 outbreak: The Vietnam lessons. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mubeen, S.M.; Kamal, S.; Kamal, S.; Balkhi, F. Knowledge and awareness regarding spread and prevention of COVID-19 among the young adults of Karachi. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 70, S169–S174. [Google Scholar]

- Kousha, K.; Thelwall, M. COVID-19 publications: Database coverage, citations, readers, tweets, news, Facebook walls, Reddit posts. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 1068–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Rosenthal, M.; Xu, S.; Arshed, M.; Li, P.; Zhai, P.; Desalegn, G.K.; Fang, Y. View of Pakistani residents toward coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during a rapid outbreak: A rapid online survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Tripathy, S.; Kar, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Verma, S.K.; Kaushal, V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102083. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S.H.; Iftikhar, M.; Mohamad, B.; Pembecioğlu, N.; Altaf, M. Precautionary behavior toward dengue virus through public service advertisement: Mediation of the individual’s attention, information surveillance, and elaboration. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020929301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Nikoo, M.; Boran, G.; Zhou, P.; Regenstein, J.M. Collagen and Gelatin. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 527–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, H.; Khalifa, H. Media Dependency during COVID-19 Pandemic and Trust in Government: The Case of Bahrain. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, J.; Zanuddin, H.; Hou, W.; Xu, J. Media attention, dependency, self-efficacy, and prosocial behaviours during the outbreak of COVID-19: A constructive journalism perspective. Glob. Media China 2022, 7, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbath, E.L.; Sparer, E.H.; Boden, L.I.; Wagner, G.R.; Hashimoto, D.M.; Hopcia, K.; Sorensen, G. Preventive care utilization: Association with individual-and workgroup-level policy and practice perceptions. Prev. Med. 2018, 111, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Lai, A.H.Y.; Wang, J.; Asim, S.; Chan, P.S.-F.; Wang, Z.; Yeoh, E.K. Multilevel determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among South Asian ethnic minorities in Hong Kong: Cross-sectional web-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e31707. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, T.A.; Duck, J.M. Communication and health beliefs: Mass and interpersonal influences on perceptions of risk to self and others. Commun. Res. 2001, 28, 602–626. [Google Scholar]

- Damstra, A.; Boukes, M.; Vliegenthart, R. The economy. How do the media cover it and what are the effects? A literature review. Sociol. Compass 2018, 12, e12579. [Google Scholar]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J. The origins of individual media-system dependency: A sociological framework. Commun. Res. 1985, 12, 485–510. [Google Scholar]

- Charanza, A.D.; Naile, T.L. Media dependency during a food safety incident related to the US beef industry. J. Appl. Commun. 2012, 96, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lowrey, W. Media dependency during a large-scale social disruption: The case of September 11. Mass Commun. Soc. 2004, 7, 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Carillo, K.; Scornavacca, E.; Za, S. The role of media dependency in predicting continuance intention to use ubiquitous media systems. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Schuldt, J.P.; Konrath, S.H.; Schwarz, N. “Global warming” or “climate change”? Whether the planet is warming depends on question wording. Public Opin. Q. 2011, 75, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The theory of planned behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skinner, C.S.; Tiro, J.; Champion, V.L. Background on the health belief model. Health Behav. Theory Res. Pract. 2015, 75, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Clubb, A.C.; Hinkle, J.C. Protection motivation theory as a theoretical framework for understanding the use of protective measures. Crim. Justice Stud. 2015, 28, 336–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chan, D.K.; Protogerou, C.; Chatzisarantis, N.L. Using meta-analytic path analysis to test theoretical predictions in health behavior: An illustration based on meta-analyses of the theory of planned behavior. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour is alive and well, and not ready to retire: A commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle, C.A.; Henly, S.J.; Larson, E. Understanding adherence to hand hygiene recommendations: The theory of planned behavior. Am. J. Infect. Control 2001, 29, 352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Reicks, M.; Sjoberg, S. Applying the theory of planned behavior to predict dairy product consumption by older adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2003, 35, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, Y.-F.; Wang, K.-L.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Pan, H.-C.; Chang, C.-J. Predictors of smoking cessation in Taiwan: Using the theory of planned behavior. Psychol. Health Med. 2018, 23, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, J.M.; Iwanaga, K.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Cotton, B.P.; Deiches, J.; Morrison, B.; Moser, E.; Chan, F. Relationships between self-determination theory and theory of planned behavior applied to physical activity and exercise behavior in chronic pain. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.; Brandes, K.; Mullan, B.; Hagger, M.S. Theory of planned behavior and adherence in chronic illness: A meta-analysis. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abu Bakar, H.; Bahtiar, M.; Halim, H.; Subramaniam, C.; Choo, L.S. Shared cultural characteristics similarities in Malaysia’s multi-ethnic society. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2018, 47, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Wong, R.M. Vaccine hesitancy and perceived behavioral control: A meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5131–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, P.; Xiao, X.; Lee, D.K.L. Narrative messages, information seeking and COVID-19 vaccine intention: The moderating role of perceived behavioral control. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggreani, G.N.; Prasetya, H.; Murti, B. Application of Theory of Planned Behavior on COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake in Palu, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Health Promot. Behav. 2023, 8, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-C.; Jung, J.-Y. SNS dependency and interpersonal storytelling: An extension of media system dependency theory. New Media Soc. 2017, 19, 1458–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S. Exploring emotional expressions on YouTube through the lens of media system dependency theory. New Media Soc. 2012, 14, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Raza, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Zaman, U.; Siang, J.M.L.D. Can Communication Strategies Combat COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy with Trade-Off between Public Service Messages and Public Skepticism? Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousaf, M.; Raza, S.H.; Mahmood, N.; Core, R.; Zaman, U.; Malik, A. Immunity debt or vaccination crisis? A multi-method evidence on vaccine acceptance and media framing for emerging COVID-19 variants. Vaccine 2022, 40, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Raza, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Munawar, R.; Shah, A.A.; Hassan, S.; Shaikh, R.S.; Ogadimma, E.C. Ingraining Polio Vaccine Acceptance through Public Service Advertisements in the Digital Era: The Moderating Role of Misinformation, Disinformation, Fake News, and Religious Fatalism. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, S.; Wakefield, M.; Kashima, Y. Can you feel it? Negative emotion, risk, and narrative in health communication. Media Psychol. 2008, 11, 52–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.; Steg, L. General beliefs and the theory of planned behavior: The role of environmental concerns in the TPB. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1817–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cho, H.; Guo, Y.; Torelli, C. Collectivism fosters preventive behaviors to contain the spread of COVID-19: Implications for social marketing in public health. Psychol. Mark. Lett. 2022, 39, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fincher, C.L.; Thornhill, R.; Murray, D.R.; Schaller, M. Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proc. R. Soc. B Boil. Sci. 2008, 275, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. The psychological measurement of cultural syndromes. Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, S.; Priesemann, V. Risking further COVID-19 waves despite vaccination. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 745–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.C. Spread of infectious disease through clustered populations. J. R. Soc. Interface 2009, 6, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rolón, V.; Geher, G.; Link, J.; Mackiel, A. Personality correlates of COVID-19 infection proclivity: Extraversion kills. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 180, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracin, D., Johnson, B.T., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.W.; Ng, L.T.; Chiang, L.C.; Lin, C.C. Antiviral effects of saikosaponins on human coronavirus 229E in vitro. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 33, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Barkoukis, V.; Wang, J.C.; Hein, V.; Pihu, M.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I. Cross-cultural generalizability of the theory of planned behavior among young people in a physical activity context. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranjit, Y.S.; Shin, H.; First, J.M.; Houston, J.B. COVID-19 protective model: The role of threat perceptions and informational cues in influencing behavior. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Klein, K.A.; Smith, S.; Martell, D. Separating subjective norms, university descriptive and injunctive norms, and US descriptive and injunctive norms for drinking behavior intentions. Health Commun. 2009, 24, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanovitzky, I.; Stewart, L.P.; Lederman, L.C. Social distance, perceived drinking by peers, and alcohol use by college students. Health Commun. 2006, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, S.S.; Poorisat, T.; Neo, R.L.; Detenber, B.H. Examining how presumed media influence affects social norms and adolescents’ attitudes and drinking behavior intentions in rural Thailand. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 282–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Smith, S.W. Distinctiveness and influence of subjective norms, personal descriptive and injunctive norms, and societal descriptive and injunctive norms on behavioral intent: A case of two behaviors critical to organ donation. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 194–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B. Contingent value measurement: On the nature and meaning of willingness to pay. J. Consum. Psychol. 1992, 1, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows-Riecken, K.H.; Rhodes, R.E.; Hoffert, K.M. Motives for lifestyle and exercise activities: A comparison using the theory of planned behaviour. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2008, 8, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Implications for public health communications. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, E.; Rehman, N.; Akhlaq, M.; Hussain, I.; Holy, O. COVID-19 vaccine reluctance and possible driving factors: A comparative assessment among pregnant and non-pregnant women. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordina, M.; Lauri, M.A. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine hesitancy and intention to take the vaccine. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twum, K.K.; Ofori, D.; Agyapong, G.K.-Q.; Yalley, A.A. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: A social marketing perspective using the theory of planned behaviour and health belief model. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 549–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Smith, L.E.; Sim, J.; Amlôt, R.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, D.T.N.; Khalil, N.R.; Le, K.; Mahdi, A.B.; Djuraeva, L. Religious beliefs and work conscience of Muslim nurses in Iraq during the COVID-19 pandemic. HTS Teol. Stud. Theol. Stud. 2022, 78, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Joshanloo, M.J.H. The relationship between fatalistic beliefs and well-being depends on personal and national religiosity: A study in 34 countries. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, Y.S.; Pong, K.S. Communicative action in COVID-19 prevention: Does religiosity play a role? Asia-Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 21, 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, S.W.; Burnett, J.J. Consumer religiosity and retail store evaluative criteria. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1990, 18, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, N.; Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Ellison, C.G.; Wulff, K.M. Aging, religious doubt, and psychological well-being. Gerontologist 1999, 39, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, C.L.; Waddington, E.; Abraham, R. Different dimensions of religiousness/spirituality are associated with health behaviors in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 2466–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, N.H.; Hvidt, N.C.; Nissen, S.P.; Storsveen, M.M.; Hvidt, E.A.; Søndergaard, J.; Thilsing, T. Religiosity and Health-Related Risk Behaviours in a Secular Culture—Is there a Correlation? J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2381–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nagel, E.; Sgoutas-Emch, S. The Relationship Between Spirituality, Health Beliefs, and Health Behaviors in College Students. J. Relig. Health 2007, 46, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.A.; Cabano, F.G. Religiosity’s influence on stability-seeking consumption during times of great uncertainty: The case of the coronavirus pandemic. Mark. Lett. 2021, 32, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G. Maintaining health and well-being by putting faith into action during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2205–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirutinsky, S.; Cherniak, A.D.; Rosmarin, D.H. COVID-19, mental health, and religious coping among American Orthodox Jews. J. Relig. 2020, 59, 2288–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Barbato, M. Positive religious coping and mental health among Christians and Muslims in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Religions 2020, 11, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire; University of Massachusetts: Amherst, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Loges, W.E. Canaries in the coal mine: Perceptions of threat and media system dependency relations. Commun. Res. 1994, 21, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, K.J.; Boyatzis, C.J. Religiosity, sense of meaning, and health behavior in older adults. Int. J. Psychol. Relig. 2010, 20, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, R.L.; McPherson, S.E. Intrinsic/extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and single-item scales. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1989, 28, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Stanford, CT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caserotti, M.; Girardi, P.; Rubaltelli, E.; Tasso, A.; Lotto, L.; Gavaruzzi, T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillon, M.; Kergall, P. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions and attitudes in France. Public Health 2021, 198, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, L.C.; Soveri, A.; Lewandowsky, S.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Nolvi, S.; Karukivi, M.; Lindfelt, M.; Antfolk, J. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 172, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Raza, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Zaman, U.; Ogadimma, E.C.; Shah, A.A.; Core, R.; Malik, A. Assessing How Risk Communication Surveillance Prompts COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Internet Users by Applying the Situational Theory of Problem Solving: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e43628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Sohail, F.; Munawar, R.; Ogadimma, E.C.; Siang, J.M.L.D. Investigating binge-watching adverse mental health outcomes during COVID-19 pandemic: Moderating role of screen time for web series using online streaming. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, ume 14, 1615–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Attributes | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 554 | 55.8% |

| Female | 439 | 44.2% | |

| Marital Status | Single | 451 | 45.4% |

| Married | 523 | 52.7% | |

| Divorced | 19 | 1.9% | |

| Educational status | High school or less | 418 | 42.1% |

| College Education | 254 | 25.6% | |

| University education | 321 | 32.3% | |

| Items | AT | BC | COL | CVI | IPC | RL | SM | SN | TM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1 | 0.860 | ||||||||

| AT2 | 0.873 | ||||||||

| AT3 | 0.820 | ||||||||

| BC1 | 0.852 | ||||||||

| BC2 | 0.838 | ||||||||

| BC3 | 0.886 | ||||||||

| COL1 | 0.770 | ||||||||

| COL2 | 0.936 | ||||||||

| COL3 | 0.909 | ||||||||

| IPC1 | 0.880 | ||||||||

| IPC2 | 0.883 | ||||||||

| IPC3 | 0.880 | ||||||||

| CVI1 | 0.870 | ||||||||

| CVI2 | 0.849 | ||||||||

| CVI3 | 0.826 | ||||||||

| RL1 | 0.879 | ||||||||

| RL2 | 0.901 | ||||||||

| RL3 | 0.834 | ||||||||

| SM1 | 0.860 | ||||||||

| SM2 | 0.864 | ||||||||

| SM3 | 0.915 | ||||||||

| SN1 | 0.804 | ||||||||

| SN2 | 0.859 | ||||||||

| SN3 | 0.798 | ||||||||

| TM1 | 0.825 | ||||||||

| TM2 | 0.893 | ||||||||

| TM3 | 0.843 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 0.811 | 0.817 | 0.888 | 0.725 |

| BC | 0.822 | 0.826 | 0.894 | 0.738 |

| COL | 0.842 | 0.845 | 0.906 | 0.765 |

| CVI | 0.806 | 0.813 | 0.885 | 0.720 |

| IPC | 0.856 | 0.858 | 0.912 | 0.776 |

| RL | 0.842 | 0.856 | 0.905 | 0.760 |

| SM | 0.856 | 0.885 | 0.911 | 0.774 |

| SN | 0.758 | 0.767 | 0.861 | 0.674 |

| TM | 0.814 | 0.816 | 0.890 | 0.730 |

| Variables | AT | BC | COL | CVI | IPC | RL | S M | SN | TM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 0.851 | ||||||||

| BC | 0.569 | 0.859 | |||||||

| COL | 0.328 | 0.381 | 0.875 | ||||||

| CVI | 0.776 | 0.545 | 0.334 | 0.849 | |||||

| IPC | 0.324 | 0.392 | 0.308 | 0.369 | 0.881 | ||||

| RL | 0.357 | 0.240 | 0.438 | 0.377 | 0.293 | 0.872 | |||

| SM | 0.415 | 0.279 | 0.466 | 0.456 | 0.268 | 0.527 | 0.880 | ||

| SN | 0.397 | 0.307 | 0.427 | 0.451 | 0.309 | 0.560 | 0.558 | 0.821 | |

| TM | 0.462 | 0.361 | 0.465 | 0.488 | 0.371 | 0.481 | 0.500 | 0.705 | 0.854 |

| Paths | Β | T Statistics | p Values | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Media → Attitude | 0.258 | 4.77 | 0.000 | H1 (a) Accepted |

| Traditional Media → CVI | 0.063 | 1.39 | 0.003 | H1 (b) Accepted |

| Social Media → Attitude | 0.198 | 3.94 | 0.000 | H2 (a) Accepted |

| Social Media → CVI | 0.097 | 2.89 | 0.004 | H2 (b) Accepted |

| Interpersonal communication → Attitude | 0.174 | 2.61 | 0.009 | H3 (a) Accepted |

| Interpersonal communication → SN | 0.196 | 4.30 | 0.000 | H3 (b) Accepted |

| Collectivism → SN | 0.367 | 7.40 | 0.000 | H4 Accepted |

| Behavioral Control → CVI | 0.129 | 3.58 | 0.000 | H5 Accepted |

| Subjective Norms → CVI. | 0.074 | 2.78 | 0.047 | H6 Accepted |

| TM → Attitude → CVI (Mediation) | 0.163 | 4.85 | 0.000 | H7 (a) Accepted |

| SM → Attitude → CVI (Mediation) | 0.120 | 3.71 | 0.000 | H7 (b) Accepted |

| (Religiosity X TM) → AT (Moderation) | −0.021 | 3.12 | 0.75 | H8 (a) Rejected |

| (Religiosity X social media) → AT(Moderation) | −0.095 | 4.87 | 0.03 | H8 (b) Accepted |

| f Square | AT | CVI | SN |

|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 0.594 | ||

| Behavioral Control | 0.131 | ||

| Collectivism | 0.316 | ||

| Interpersonal communication | 0.135 | 0.244 | |

| Religiosity | 0.103 | ||

| Religiosity X TM | 0.115 | ||

| Religiosity X social media | 0.003 | ||

| Social Media | 0.263 | 0.121 | |

| Subjective Norms | 0.107 | ||

| Traditional Media | 0.327 | 0.095 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, M.; Raza, S.H.; Yousaf, M.; Zaman, U.; Jin, Q. Investigating the Psychological, Social, Cultural, and Religious Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention in Digital Age: A Media Dependency Theory Perspective. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081338

Ma M, Raza SH, Yousaf M, Zaman U, Jin Q. Investigating the Psychological, Social, Cultural, and Religious Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention in Digital Age: A Media Dependency Theory Perspective. Vaccines. 2023; 11(8):1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081338

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Mengyao, Syed Hassan Raza, Muhammad Yousaf, Umer Zaman, and Qiang Jin. 2023. "Investigating the Psychological, Social, Cultural, and Religious Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention in Digital Age: A Media Dependency Theory Perspective" Vaccines 11, no. 8: 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081338

APA StyleMa, M., Raza, S. H., Yousaf, M., Zaman, U., & Jin, Q. (2023). Investigating the Psychological, Social, Cultural, and Religious Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Intention in Digital Age: A Media Dependency Theory Perspective. Vaccines, 11(8), 1338. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081338