Acceptability of HPV Vaccines: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Summary

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Selecting and Reading Primary Research

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis of Results

3. Results

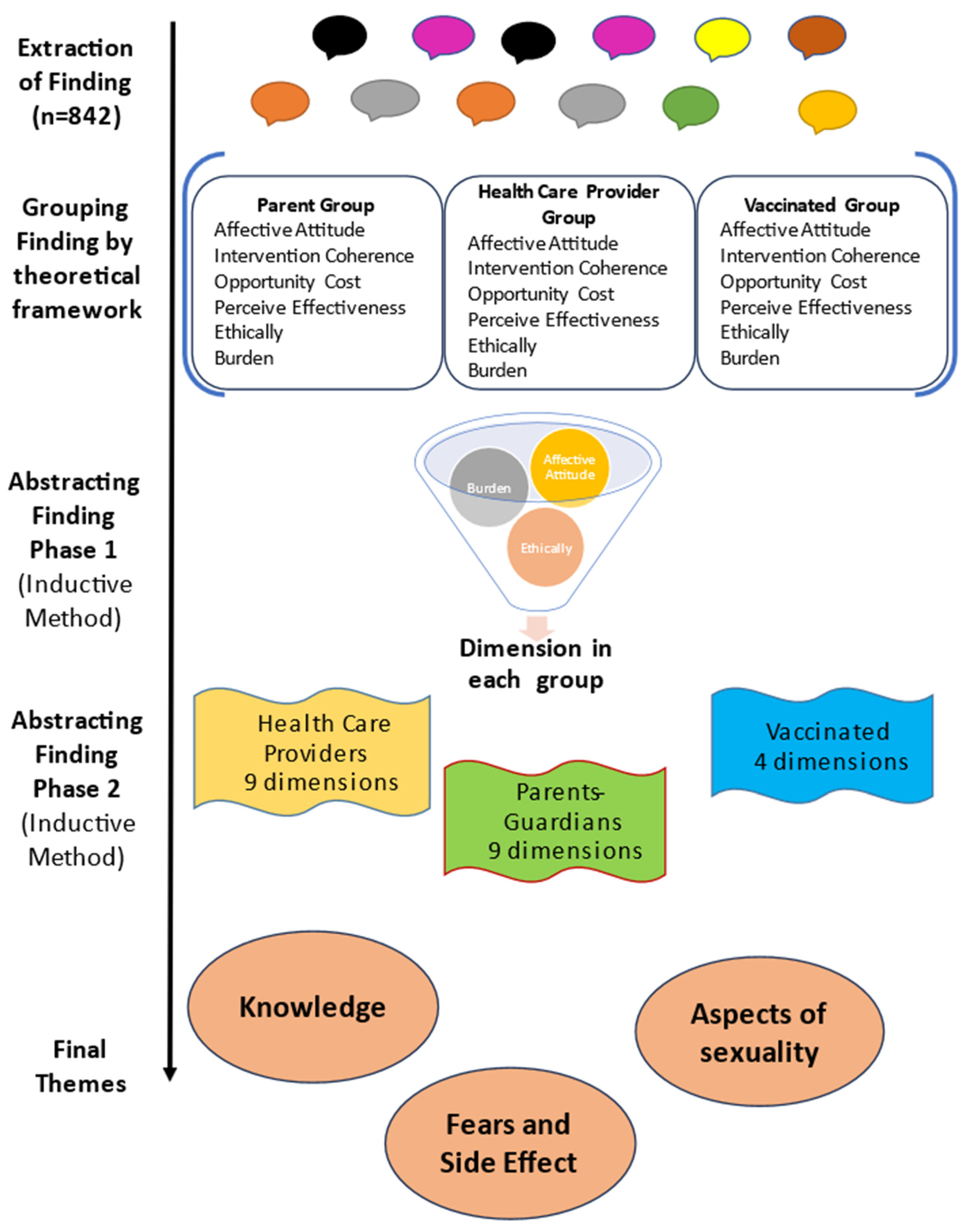

3.1. Extraction of Findings: “This Stage Entails Distinguishing the Specific Finding You Want to Integrate from All Other Elements in the Research Reports Containing Those Finding” [9]

3.2. Editing Findings: “Once You Have Finished Extracting Findings, You Should Edit Them to Make Them Accessible as Possible to Any Reader” [9]

3.3. Grouping Findings: “To Group Findings That Appear to Be the Same Topic” [9]

3.4. Abstraction of the Findings: “In the Abstraction Process, You Will Further Reduce the Many Statements of Findings You Extracted, Edited, and Grouped into More Parsimonious Rendering of Them” [9]

3.4.1. Phase 1: Generating New Categories

3.4.2. Phase 2: Generating Dimensions from the New Categories

3.5. Calculating Manifest Frequency and Intensity Effect Sizes: “The Calculation of Effect Sizes Constitutes a Quantitative Transformation of Qualitative Data in the Service of Extracting More Meaning from Those Data and Verifying the Presence of a Pattern or Theme” [9]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Collado, J.J.; Gómez, D.; Muñoz, J.; Bosch, F.X.; de Sanjosé, S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in the World. Summary Report 10 March 2023. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/ZAF.pdf?t=1668367618799 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. Geneva 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Yousefi, Z.; Aria, H.; Ghaedrahmati, F.; Bakhtiari, T.; Azizi, M.; Bastan, R.; Hosseini, R.; Eskandari, N. An Update on Human Papilloma Virus Vaccines: History, Types, Protection, and Efficacy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 805695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, L.; Saura-Lázaro, A.; Montoliu, A.; Brotons, M.; Alemany, L.; Diallo, M.S.; Afsar, O.Z.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Mosina, L.; Contreras, M.; et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010–2019. Prev. Med. 2021, 144, 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.; Cartwright, M.; Francis, J.J. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M.; Barroso, J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Perkins, R.B.; Chigurupati, N.L.; Apte, G.; Vercruysse, J.; Wall-Haas, C.; Rosenquist, A.; Lee, L.; Clark, J.A.; Pierre-Joseph, N. Why don’t adolescents finish the HPV vaccine series? A qualitative study of parents and providers. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 1528–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, A.F.; Abraham, L.M.; Dalton, V.; Ruffin, M. Understanding the Reasons Why Mothers Do or Do Not Have Their Adolescent Daughters Vaccinated Against Human Papillomavirus. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottvall, M.; Grandahl, M.; Höglund, A.T.; Larsson, M.; Stenhammar, C.; Andrae, B.; Tydén, T. Trust versus concerns—How parents reason when they accept HPV vaccination for their young daughter. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2013, 118, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumling, A.A.; Thomas, T.L.; Stephens, D.P. Researching and Respecting the Intricacies of Isolated Communities. Online J. Rural Nurs. Health Care 2013, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio, A.M.; Ward, K.K.; Carmack, C.C.; Muñoz, B.T.; Cano, M.A.; Cribbs, F. Using Social Marketing Theory as a Framework for Understanding and Increasing HPV Vaccine Series Completion among Hispanic Adolescents: A Qualitative Study. J. Community Health 2016, 42, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottvall, M.; Stenhammar, C.; Grandahl, M. Parents’ views of including young boys in the Swedish national school-based HPV vaccination programme: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandahl, M.; Oscarsson, M.; Stenhammar, C.; Nevéus, T.; Westerling, R.; Tydén, T. Not the right time: Why parents refuse to let their daughters have the human papillomavirus vaccination. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, M.J.; Tufts, K.A. Implications of the Virginia Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Mandate for Parental Vaccine Acceptance. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 23, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.L.; Lai, D.; Carbajal-Salisbury, S.; Garza, L.; Bodson, J.; Mooney, K.; Kepka, D. Latino Parents’ Perceptions of the HPV Vaccine for Sons and Daughters. J. Community Health 2014, 40, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.E.; Le, Y.-C.L.; Fernández-Espada, N.; Calo, W.A.; Savas, L.S.; Vélez, C.; Aragon, A.P.; Colón-López, V. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs About Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination among Puerto Rican Mothers and Daughters, 2010: A Qualitative Study. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.; Wardle, J.; Waller, J. Attitudes to HPV vaccination among ethnic minority mothers in the UK: An exploratory qualitative study. Hum. Vaccines 2009, 5, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciun, C.; Baban, A. “Who will take the blame?”: Understanding the reasons why Romanian mothers decline HPV vaccination for their daughters. Vaccine 2012, 30, 6789–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio, A.M.; Muñoz, B.T.; Carmack, C.C.; Ward, K.K.; A Cano, M.; Cribbs, F.L.; Fernandez-Espada, N. Understanding HPV vaccine initiation in Hispanic adolescents using social marketing theory. Health Educ. J. 2019, 78, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Btoush, R.; Brown, D.R.; Tsui, J.; Toler, L.; Bucalo, J. Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among Latina Mothers of South American and Caribbean Descent in the Eastern US. Health Equity 2019, 3, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, D.; Petrovic, K.; Grech, C.; Harris, N. HPV vaccination in women aged 27 to 45 years: What do general practitioners think? BMC Women’s Health 2014, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubens-Augustson, T.; Wilson, L.A.; Murphy, M.S.; Jardine, C.; Pottie, K.; Hui, C.; Stafström, M.; Wilson, K. Healthcare provider perspectives on the uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine among newcomers to Canada: A qualitative study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 15, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, K.J.; Vanderpool, R.C.; Mills, L.A. Health Care Providers’ Perspectives on Low HPV Vaccine Uptake and Adherence in Appalachian Kentucky. Public Health Nurs. 2013, 30, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockliffe, L.; McBride, E.; Heffernan, C.; Forster, A.S. Factors Affecting Delivery of the HPV Vaccination: A Focus Group Study with NHS School-Aged Vaccination Teams in London. J. Sch. Nurs. 2018, 36, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartmell, K.B.; Young-Pierce, J.; McGue, S.; Alberg, A.J.; Luque, J.S.; Zubizarreta, M.; Brandt, H.M. Barriers, facilitators, and potential strategies for increasing HPV vaccination: A statewide assessment to inform action. Papillomavirus Res. 2017, 5, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart, M.Y.; Schminkey, D.L.; Mitchell, E.M.; Keim-Malpass, J. Barriers and Facilitators to Improving Virginia’s HPV Vaccination Rate: A Stakeholder Analysis with Implications for Pediatric Nurses. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, R. Understanding Provider Barriers to Recommending and Administering the HPV Vaccine to Adolescents in Colorado: A Mixed Method Approach; University of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.H.; Sobel, K.B.; Roth, L.M.; Byron, S.C.M.; Lindley, M.C.; Stokley, S.D. Supporting Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Adolescents: Perspectives from Commercial and Medicaid Health Plans. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2017, 23, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanbakht, M.; Stahlman, S.; Walker, S.; Gottlieb, S.; Markowitz, L.; Liddon, N.; Plant, A.; Guerry, S. Provider perceptions of barriers and facilitators of HPV vaccination in a high-risk community. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4511–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, H.; Schrimpf, C.; Moro, M.R.; Lachal, J. HPV vaccination rate in French adolescent girls: An example of vaccine distrust. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 103, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscarsson, M.G.; Hannerfors, A.-K.; Tydén, T. Young women’s decision-making process for HPV vaccination. Sex. Reprod. Health 2012, 3, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.K.; Wickliffe, J.; Jahnke, S.; Linebarger, J.; Humiston, S.G. Views on Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Mixed-Methods Study of Urban Youth. J. Community Health 2014, 39, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Okoror, T.A.; Hyner, G.C. Focus Group Study of Chinese International Students’ Knowledge and Beliefs About HPV Vaccination, Before and After Reading an Informational Pamphlet About Gardasil®. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, E.; Whittaker, A.; Brunton, C.G.; Hogg, R.; Kennedy, C.; Hilton, S.; Harding, S.; Pollock, K.G.; Pow, J. Development of a cross-cultural HPV community engagement model within Scotland. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, J.Y.-M. Barriers to receiving human papillomavirus vaccination among female students in a university in Hong Kong. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.S.E.; Lim, R.B.T. Facilitators and barriers of human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young females 18–26 years old in Singapore: A qualitative study. Vaccine 2019, 37, 6030–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Newman, P.; Logie, C.H.; Doukas, N.; Asakura, K. HPV vaccine acceptability among men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2013, 89, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambout, L.; Tashkandi, M.; Hopkins, L.; Tricco, A.C. Self-reported barriers and facilitators to preventive human papillomavirus vaccination among adolescent girls and young women: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2014, 58, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadarzynski, T.; Smith, H.; Richardson, D.; Jones, C.J.; Llewellyn, C.D. Human papillomavirus and vaccine-related perceptions among men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2014, 90, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, M.S.; Davison, C.; Aronson, K.J. HPV vaccine acceptability in Africa: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisic, G.; Chapman, J.; Flight, I.; Wilson, C. Factors associated with parents’ attitudes to the HPV vaccination of their adolescent sons: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2016, 95, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, S.E.; Kenzie, L.; Letendre, A.; Bill, L.; Shea-Budgell, M.; Henderson, R.; Barnabe, C.; Guichon, J.R.; Colquhoun, A.; Ganshorn, H.; et al. Barriers and supports for uptake of human papillomavirus vaccination in Indigenous people globally: A systematic review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, H.; Lim, R.; Gill, P.K.; Dhanoa, J.; Dubé, È.; Bettinger, J.A. What do adolescents think about vaccines? Systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0001109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, H.B.; Trotter, C.; Hickman, M.; Audrey, S. Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination of young women in high-income countries: A qualitative systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somefun, O.D.; Casale, M.; Ronnie, G.H.; Desmond, C.; Cluver, L.; Sherr, L. Decade of research into the acceptability of interventions aimed at improving adolescent and youth health and social outcomes in Africa: A systematic review and evidence map. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e055160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzuta, D.; Jaworski, M.; Gotlib, J.; Panczyk, M. Characteristics of Antivaccine Messages on Social Media: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palencia-Sánchez, F.; Echeverry-Coral, S.J. Social considerations affecting acceptance of HPV vaccination in Colombia. A systematic review. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2020, 71, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.; Trotter, C.L.; Audrey, S.; MacDonald-Wallis, K.; Hickman, M. Inequalities in the uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk. Res. 2013, 42, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorji, T.; Nopsopon, T.; Tamang, S.T.; Pongpirul, K. Human papillomavirus vaccination uptake in low-and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 34, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentschke, M.; Kampers, J.; Becker, J.; Sibbertsen, P.; Hillemanns, P. Prophylactic HPV vaccination after conization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6402–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucyibaruta, J.B.; Peu, D.; Bamford, L.; Van der Wath, A. Closing the gaps in defining and conceptualising acceptability of healthcare: A qualitative thematic content analysis. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, N.T.; Fazekas, K.I. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, P.; Wallington, S.F.; Greaney, M.L.; Lindsay, A.C. Exploring HPV Knowledge, Awareness, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Vaccine Acceptability of Latino Fathers Living in the United States: An Integrative Review. J. Community Health 2019, 44, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. HPV Vaccine Comunication. Special Considerations for a Unique Vaccine. 2016 Update Geneva 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IVB-16.02 (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Gamaoun, R. Knowledge, awareness and acceptability of anti-HPV vaccine in the Arab states of the Middle East and North Africa Region: A systematic review. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Newman, P.A.; Baiden, P. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability and decision-making among adolescent boys and parents: A meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabakama, S.; Gallagher, K.E.; Howard, N.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Burchett, H.E.D.; Griffiths, U.K.; Feletto, M.; LaMontagne, D.S.; Watson-Jones, D. Social mobilisation, consent and acceptability: A review of human papillomavirus vaccination procedures in low and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.; Fleming, A.; Moore, A.; Sahm, L. Views of parents regarding human papillomavirus vaccination: A systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis of qualitative literature. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Ochoa, C.Y.; Murphy, S.T.; Moran, M.B.; Rodriguez, Y.L.; Barahona, R.; Garcia, L. Es Tiempo: Engaging Latinas in Cervical Cancer Research. In Advancing the Science of Cancer in Latinos; Ramirez, A.G., Trapido, E.J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Campos, D.Y.; Snipes, S.A.; Villarreal, E.K.; Crocker, L.C.; Guerrero, A.; Fernandez, M.E. Cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV), and HPV vaccination: Exploring gendered perspectives, knowledge, attitudes, and cultural taboos among Mexican American adults. Ethn. Health 2018, 26, 206–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ver, A.T.; Notarte, K.I.; Velasco, J.V.; Buac, K.M.; Nazareno, J.; Lozañes, J.A.; Antonio, D.; Bacorro, W. A systematic review of the barriers to implementing human papillomavirus vaccination programs in low- and middle-income countries in the Asia-Pacific. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 17, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update). Relev. Épidémiol. Hebd. 2022, 97, 647–672. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Study aim | Adherence to and/or acceptability of the vaccine |

| Type of study |

|

| Study group |

|

| Population | Studies conducted on healthy population with a normal risk of contracting HPV |

| Type of analysis 2 |

|

| First Author (Ref) | Group of Study | Country | Sample Description | Ages of the Samples (Years) | Gender | Data Collection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perkins [12] | Parents | United States | Parents of girls with two or three doses of vaccine (n = 65) | 41 to 49 | Both | Interview |

| Dempsey [13] | Parents | United States | Mothers of adolescents aged between 11 and 17 years (n = 52) | 40 to 44 | Women | Telephone interview |

| Gottvall [14] | Parents | Sweden | Parents who allowed the vaccination of their daughters aged between 11 and 12 years (n = 29) | 44 | Both | Interview |

| Blumbling [15] | Parents | United States | Parents over the age of 18 years with a child between the ages of 9 and 13 (n = 18) | 35 to 60 | Both | Focus group |

| Roncancio [16] | Parents | United States | Latina mothers of boys and girls between the ages of 11 and 17 years (n = 51) | 42 | Women | Interview |

| Gottvall [17] | Parents | Sweden | Parents of girls aged between 11 and 12 years (n = 42) | Average: 43 | Both | Interview |

| Grandahl [18] | Parents | Sweden | Parents who refused to vaccinate their daughters (n = 23) | Average: 44 | Both | Interview |

| Pitts [19] | Parents | United States | Parents/caregivers of girls aged 9–13 years (n = 33) | No information | Both | Focus group |

| Warner [20] | Parents | United States | Parents of Latino boys/girls aged 11–17 years (n = 52) | 18 to 50 | Both | Focus group |

| Fernández [21] | Parents | Puerto Rico | Mothers of daughters aged between 16 and 26 years (n = 30) | Average: 47.9 | Women | Focus group |

| Marlow [22] | Parents | United Kingdom | Mothers with at least one daughter aged less than 16 years (n = 20) | No information | Women | Interview |

| Craciun [23] | Parents | Romania | Mothers of girls in the vaccine target group (n = 25) | 30 to 50 | Women | Focus group and interview |

| Roncancio [24] | Parents | United States | Spanish-speaking Hispanic mothers of adolescent girls and boys aged 11–17 years (n = 85) | Average: 39 | Women | Interview |

| Btoush [25] | Parents | United States | Latina mothers of HPV-vaccine-eligible children (n = 132) | 40 (50%) | Women | Focus group |

| Perkins, 2016 [12] | Health care providers | United States | Healthcare providers (n = 33) | No information | No information | Interview |

| Mazza [26] | Health care providers | Australia | General practitioners (n = 24) | 34 to 75 Average: 49 | Both | Telephone interview |

| Rubens–Augustson [27] | Health care providers | Canada | Family physicians (n = 8), nurse practitioners (n = 2), and a gynecologist (n = 1) | 18 to 56 | Both | Interview |

| Head [28] | Health care providers | United States | Nurse practitioners (n = 3), licensed practical nurses (n = 4), and a medical doctor (n = 1) | Average: 38.8 | Women | Interview |

| Rockliffe [29] | Health care providers | United Kingdom | Healthcare providers (n = 28) | No information | Both | Focus group |

| Cartmell [30] | Health care providers | United States | State leaders with the potential to influence vaccination policies and practices (n = 34) | 45 to 64 | Both | Interview |

| Carhart [31] | Health care providers | United States | Stakeholders involved with aspects of care directly related to HPV vaccination, policy, industry, research, or cancer outreach/community engagement (n = 31) | No information | Both | Interview |

| Ayele [32] | Health care providers | United States | Healthcare providers (n = 26) | No information | Both | Interview |

| Ng [33] | Health care providers | United States | Health plan directors (n = 10) | No information | No information | Interview |

| Javanbakht [34] | Health care providers | United States | Physicians (n = 4), a physician’s assistant (n = 1), medical assistants (n = 7), and case managers (n = 9) | No information | Both | Interview |

| Lefevre [35] | Health care providers | France | Physicians (n = 16) | No information | No information | Interview |

| Fernández [21] | Vaccinated | Puerto Rico | Women aged between 16 and 26 years (n = 30) | Average: 20.4 | Women | Focus group |

| Oscarsson [36] | Vaccinated | Sweden | Women (n = 16) | 17 to 26 | Women | Interview |

| Miller [37] | Vaccinated | United States | Adolescents (n = 50) | 14 to 18 | Both | Focus group |

| Gao [38] | Vaccinated | United States | People aged between 18 and 34 years (n = 44) | Average: 24.6 | Both | Focus group |

| Carnegie [39] | Vaccinated | Scotland | People aged between 16 and 26 years (n = 40) | 16 to 26 | Both | Focus group and interview |

| Siu [40] | Vaccinated | Hong Kong | Undergraduate Chinese students (n = 35) | 19 to 23 | Women | Interview |

| Lim [41] | Vaccinated | Singapore | Female students (n = 40) | 18 to 26 | Women | Focus group and interview |

| Groups under Study | AA | B | E | IC | OC | PE | SE | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grouping findings | Healthcare providers | 76 | 106 | 55 | 97 | 18 | 38 | 0 | 390 |

| Parents | 47 | 88 | 27 | 91 | 6 | 51 | 0 | 310 | |

| Vaccinated individuals | 19 | 16 | 27 | 60 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 142 | |

| 142 | 210 | 109 | 248 | 27 | 106 | 0 | 842 | ||

| Abstracting findings (phase 1) | Healthcare providers | 18 | 15 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 8 | -- | 63 |

| Parents | 11 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 9 | -- | 45 | |

| Vaccinated individuals | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | -- | 19 | |

| 32 | 27 | 17 | 23 | 8 | 20 | -- | 127 |

| Groups under Study | Dimensions | Components of the Model to Which the Categories Belong |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare providers | 1. Cost and public policies related to vaccines | 7 components: AA-B-E-IC-OC-PE |

| 2. Vaccine information and education | 4 components: AA-B-IC-OC | |

| 3. Lack of time/other priorities | 5 components: AA-B-IC-OC-PE | |

| 4. Associated between vaccination and sexuality | 2 components: E-IC | |

| 5. Record and reminder systems | 4 components: B-IC-OC-PE | |

| 6. Vaccine safety/fears | 3 components: AA-B-PE | |

| 7. Strategies for promoting vaccination | 4 components: AA-B-IC-PE | |

| 8. Vaccine mandatory/decision/doses | 4 components: AA-B-E-PE | |

| 9. Cultural and language differences | 3 components: AA-B-E | |

| Parents/guardians | 1. Information is needed | 5 components: AA-B-E-IC-PE |

| 2. The vaccine is beneficial and necessary | 3 components: AA-IC-PE | |

| 3. The vaccine may cause harm/side effects | 3 components: AA-B-PE | |

| 4. Vaccination is associated with sexuality and gender roles | 5 components: AA-B-E-IC-PE | |

| 5. The vaccine is mandatory (trust or mistrust) | 4 components: AA-E-PE | |

| 6. Vaccine cost and access | 2 components: B-OC | |

| 7. Decision to vaccinate | 4 components: AA-B-IC-PE | |

| 8. Age upon vaccination | 2 components: AA-IC | |

| 9. Reminders to vaccinate | 3 components: B-IC-PE | |

| Vaccinated individuals | 1. Knowledge about vaccines | 5 components: AA-B-E-IC-PE |

| 2. Risk perception and associated fears | 4 components: AA-B-E-PE | |

| 3. Vaccination is associated with sexuality and gender roles | 3 components: E-IC-PE | |

| 4. Cost and number of doses of vaccines | 2 components: B-OC |

| Categories | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Providers | Parents/Guardians | Vaccinated Individuals | |||||||||||||||||||||

| First Author, Year (Cite) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Intensity Effect Size |

| Perkins, 2016 [12] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | - | - | - | - | 56% |

| Dempsey, 2009 [13] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | - | - | - | - | 33% |

| Gottvall, 2013 [14] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | 67% |

| Blumling, 2014 [15] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | - | - | - | - | 22% |

| Roncancio, 2017 [16] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | - | - | - | 78% | |

| Gottvall, 2017 [17] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | - | - | - | - | 33% |

| Grandahl, 2014 [18] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | 56% |

| Pitts, 2013 [19] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | 78% |

| Warner, 2015 [20] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | - | - | - | - | 44% |

| Fernández, 2014 [21] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | - | - | - | - | 56% |

| Marlow, 2009 [22] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | - | - | - | - | 67% |

| Craciun, 2012 [23] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | - | - | - | - | 56% |

| Roncancio, 2019 [24] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | - | - | - | - | 56% |

| Btoush, 2019 [25] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | 44% |

| Perkins, 2016 [12] | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 22% |

| Mazza, 2014 [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77% |

| Rubens- Augustson, 2019 [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77% |

| Head, 2013 [28] | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 66% |

| Rockliffe, 2020 [29] | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 44% |

| Catmell, 2018 [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 89% |

| Carhart, 2018 [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100% |

| Ayele, 2018 [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 55% |

| Ng, 2017 [33] | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 55% |

| Javanbakht, 2012 [34] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77% |

| Lefevre, 2018 [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77% |

| Oscarson, 2012 [36] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Miller, 2014 [37] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | No | No | 50% |

| Fernández, 2014 [21] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Gao, 2016 [38] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 75% |

| Carnegie, 2017 [39] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | No | No | 50% |

| Siu, 2013 [40] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Lim, 2019 [41] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Frequency effect size | 64% | 91% | 55% | 73% | 55% | 64% | 91% | 91% | 27% | 86% | 43% | 79% | 64% | 50% | 43% | 71% | 29% | 21% | 100% | 100% | 71% | 57% | |

| Knowledge | This theme reveals the lack of information regarding HPV vaccination in the three groups of respondents and their interest in this regard. Such information enables users to make informed decisions and professionals to prescribe the vaccines. Parents and vaccinated individuals indicate that they lack understanding of the information given to them. In turn, professionals report the need for patients to receive education, and that the information must be consistent. Without truthful information, discussion of and, therefore, adherence to the vaccine become difficult. | |

| Healthcare providers | “You never hear a patient say, I think I have HPV … since the research started, we became more knowledgeable and more apt to talk to them about [HPV].” [28] | |

| Parents/ guardians | “We haven’t received any explanation … no information about HPV has been given. The only thing we got was a vaccination appointment.” [18] | |

| Vaccinated individuals | “I have heard about it [HPV], but I don’t know what it is.” [21] | |

| Fears and Side effect | This theme unveils all aspects associated with perceived barriers to receiving vaccination and the caution that people exercise in relation to the safety and effectiveness of vaccines. Side effects are part of this theme, as is the risk perception of vaccinated individuals | |

| Healthcare professionals | “From the other side there are questions: How old is the vaccine? Is this a clinical trial? Are we guinea pigs?” [30] | |

| Parents/ guardians | “I just don’t know enough about it. That’s reason number one and then I don’t want her to fall into a category where she gets this done and then ten years down the line they find that it reacts a different way. So it’s a little bit frightening for me.” [13] | |

| Vaccinated | “What chemicals are they putting inside the HPV shot … How can we trust it?” [37] | |

| Aspects of sexuality | The relationship between the vaccine and sexuality reveals multiple aspects, such as the risk of promoting sexual activity and even promiscuity, because they would be reducing the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases; the need to talk about sexuality and the difficulty associated with this discussion; the age group at which the vaccine is directed; the perception that it is a vaccine only for women; and religious aspects considered by a number of participants | |

| Healthcare providers | “Well, their concern is the same. They tell you over and over the same, ‘I don’t want my child to have sex, so I don’t want to give the vaccine to my girl ‘cause she’s gonna start having sex.’ And the same, sex, sex, sex.” [34] | |

| Parents/ guardians | “I think [the HPV vaccine] is important, but I have to inform my son why I’m giving him the vaccine. Sex education is very important, but sometimes as a Hispanic parent we try to avoid those issues ….” [20] | |

| Vaccinated individuals | “I won’t get the vaccine, because I am not [having sex]. Thus, I am not going to get the vaccine. [I will get the] injection before I get married, together with the premarital checkup.” [38] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Urrutia, M.-T.; Araya, A.-X.; Gajardo, M.; Chepo, M.; Torres, R.; Schilling, A. Acceptability of HPV Vaccines: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Summary. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11091486

Urrutia M-T, Araya A-X, Gajardo M, Chepo M, Torres R, Schilling A. Acceptability of HPV Vaccines: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Summary. Vaccines. 2023; 11(9):1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11091486

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrrutia, María-Teresa, Alejandra-Ximena Araya, Macarena Gajardo, Macarena Chepo, Romina Torres, and Andrea Schilling. 2023. "Acceptability of HPV Vaccines: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Summary" Vaccines 11, no. 9: 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11091486

APA StyleUrrutia, M.-T., Araya, A.-X., Gajardo, M., Chepo, M., Torres, R., & Schilling, A. (2023). Acceptability of HPV Vaccines: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-Summary. Vaccines, 11(9), 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11091486