Vaccine Hesitancy among Immigrants: A Narrative Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned

Abstract

1. Introduction

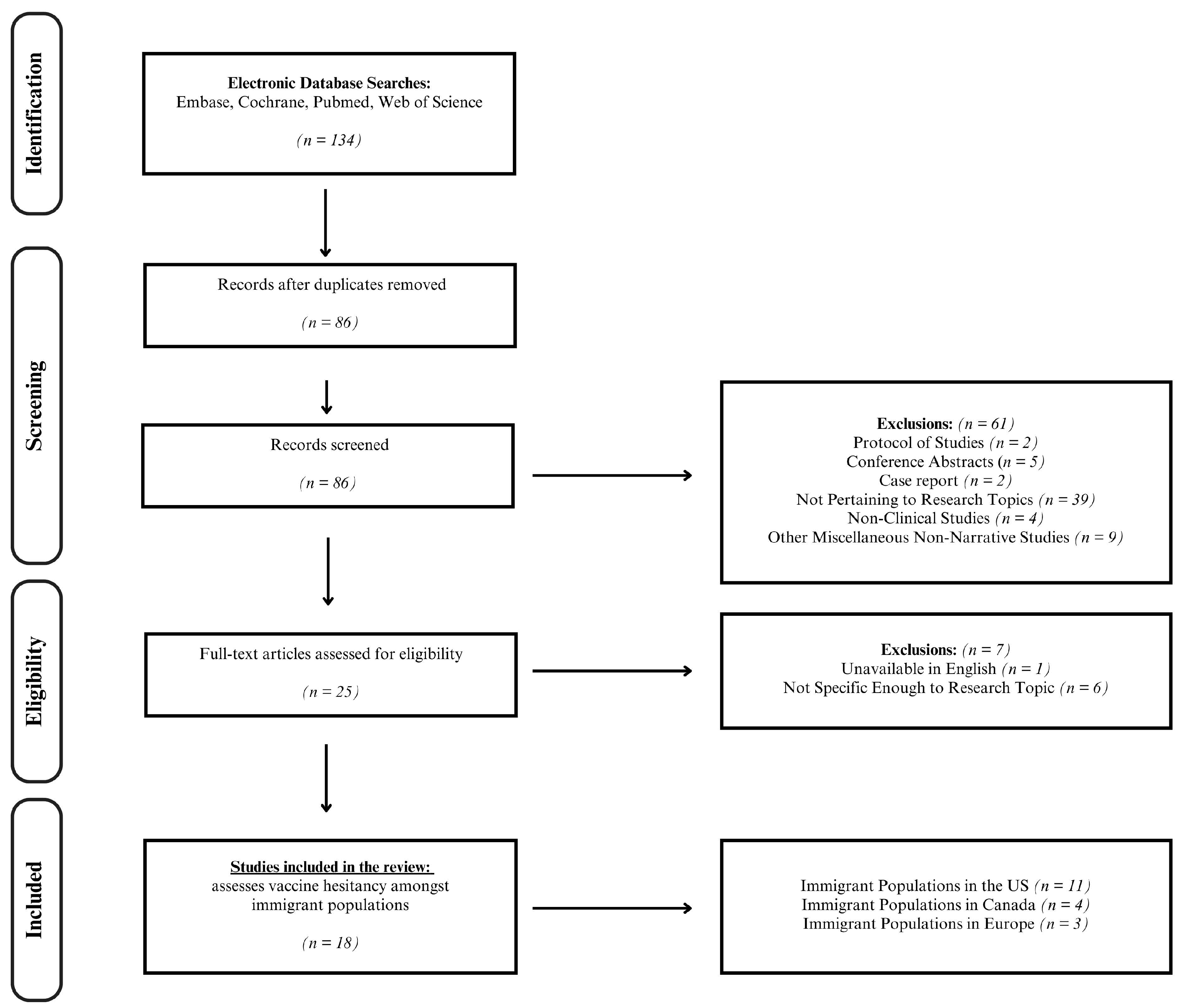

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Vaccination Rates

3.2. Barriers to Vaccination

| Location | Study | Study Design | Risk of Bias (Appraisal Tool) | Study Time Period | Vaccine | Population Examined | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | Aktürk et al., 2021 [20] | Cross-sectional | Low-Moderate (AXIS) | February 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Turkish- and German-speaking people with migratory background in Munich | 420 |

| Svallfors et al., 2023 [12] | Cross-sectional | Low-Moderate (AXIS) | April to May 2021 and August to September 2021 | COVID-19 1 | First-generation immigrants (age 16+ years) in Sweden | 1809 | |

| Penot et al., 2023 [21] | Cross-sectional | Low (AXIS) | 5 January to 1 June 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Immigrant adults with HIV living in Seine-Saint-Denis France | 296 | |

| North America | Lin 2022 [30] | Cross-sectional | Low-Moderate (AXIS) | 15–21 June 2020 | COVID-19 1 | Im/migrants age 25+ in Canada | 3522 |

| Bajgain et al., 2022 [32] | Cross-sectional | Moderate (AXISs) | October 2020 | COVID-19 1 | 16 years and up in Alberta, Canada (born in vs. outside of Canada) | 10,175 | |

| Stratoberdha et al., 2022 [34] | Qualitative systematic review | Moderate-High (AMSTAR 2) | 1946 to January 2021 (MEDLINE) and 1974 to January 2021 (EMBASE) | HBV 2/HPV 3 | Canada | ||

| Wanigaratne et al., 2023 [22] | Retrospective population-based cohort study | Low-Moderate (NOS) | 13 September 2021 and 13 March 2022 | COVD-19 1 | Canada | 11,844,221 | |

| Painter et al., 2019 [37] | Qualitative study | Moderate (CASP) | March to September 2016 | Tdap 4, MenACWY 5, HPV 3 | Latin American immigrant mothers living in Virginia, US | 30 | |

| Zhang et al., 2021 [25] | Cross-sectional | Moderate (AXIS) | December 2020 to January 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Afghan, Bhutanese, Somali, South Sudanese, and Burmese refugee committees in the US | 435 | |

| McFadden et al., 2022 [23] | Narrative review | Fair/Poor Quality (SANRA) | September 2020 to April 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Undocumented Hispanic immigrant community US | ||

| Sudhinaraset, Nwankwo, and Choi 2022 [29] | Cross-sectional | Low-Moderate (AXIS) | September 2020 to February 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Undocumented immigrants in California, USA | 326 | |

| Malone et al., 2022 [33] | Case control | Moderate-High (NOS) | 6 January to 28 May 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Refugees from Bosnia, Kosovo, Liberia, Congo, Burundi, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Iraq, Syria, Bhutan, Burma, Afghanistan, and Pakistan living in Clarkston, Georgia, USA | 3127 | |

| Ogunbajo and Ojikutu 2022 [24] | Cross-sectional | High (AXIS) | January to February 2021 | COVID-19 1 | 1st- and 2nd-generation Black immigrants in the US | 388 | |

| Allen et al., 2022 [38] | Cross-sectional | Low-Moderate (AXIS) | July to August 2020 | COVID-19 1 | Brazilian immigrant women ages 18+ in the US | 353 | |

| Daniels et al., 2022 [31] | Systematic review & Meta analysis | Moderate (AMSTAR 2) | April 2012 to May 2022 | Foreign-born individuals ages 18+ that resettles within the US | |||

| Kirchoff et al., 2023 [26] | Cross-sectional | Low-Moderate (AXIS) | October 2020 to February 2021 | COVID-19 1 | Adult Latinx immigrants in South Florida, USA | 191 | |

| Valero-Martínez et al., 2023 [28] | Mixed methods study | High (MMAT) | 2021 | COVID-19 1 | ethnically/racially diverse adults born outside of the US | 100 | |

| Sharp et al., 2024 [27] | Mixed methods study | Low (MMAT) | February to August 2022 | COVID-19 1 | Immigrant communities in the Chicago metropolitan area | 402 |

| Study | Rates of Vaccine Hesitancy | Conclusions | Contributing Factors to Vaccine Hesitancy | Lessons Learned | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mis- Information | Lack of Knowledge | Safety Concern | Personal Beliefs | Language Barriers | Immigrant Status | Access to Vaccine | ||||

| Aktürk et al., 2021 [20] | A total of 90.08% immigrant Germans surveyed did not consider becoming vaccinated | Turkish-origin people in Germany face social disadvantages and declining health across generations. Members of ethnic minority groups and vulnerable migrant populations exhibit reduced acceptance of vaccines. | X | X | X | To address vaccination hesitancy, clear and individualized information campaigns are important. Engaging trainers from the community can enhance acceptance and address distrust, potentially stemming from discriminatory attacks against immigrants. | ||||

| Svallfors et al., 2023 [12] | A total of 25% of first-generation immigrants in Sweden surveyed (ages 16+) had some degree of vaccine hesitancy | Trust in healthcare providers and government authorities is crucial. Providing targeted vaccine information to those who face barriers to care can help make informed decisions about vaccination relating to health risks. | X | Governmental and healthcare entities need to confront various social determinants that contribute to low vaccination rates and disparities in health outcomes for first-generation immigrants | ||||||

| Penot et al., 2023 [21] | A total of 67.9% of immigrant participants held spontaneous unacceptance | The ICOVIH survey found that the already disadvantaged immigrant PLWHIV became more vulnerable during the first lockdown. However, they were confident in their physician’s recommendations and caught up with vaccination rates like those of PLWHIV born in France. | X | X | Patients depend on doctors to implement preventative measures for the most vulnerable populations, especially during the emergence and re-emergence of viruses, and with the development of new mRNA vaccines. Healthcare providers are essential in giving information and support to people dealing with chronic illnesses and social challenges. | |||||

| Lin 2022 [30] | Not mentioned in the study | The research has shown differences based on birthplace, income, and education levels regarding COVID-19-related health concerns and reasons for refusing vaccination, even within the context of universal health coverage in Canada. | X | X | X | X | When organizing COVID-19 vaccinations in countries with many immigrants, patients, regardless of their legal status, can easily get vaccines and healthcare. The government and medical institutions should ensure fair access, and they must be responsible for this. Given the emergence of new virus variants, it is especially important to focus on health fairness and address the pandemic’s unequal impact on underserved communities. | |||

| Bajgain et al., 2022 [32] | Not mentioned in the study | The research underscores the importance of introducing a cost-effective community-based intervention, placing a priority on enhanced mental health care for all. This strategy is crucial for promoting and improving access to healthcare services. | X | X | X | The rising interest in virtual care highlights the importance of investing in technology and incorporating primary care to provide effective virtual care services. Patient education on the virtual care process is vital. | ||||

| Stratoberdha et al., 2022 [34] | Not mentioned in the study | The immigrants of the Canadian population can greatly benefit from improving healthcare access and increasing vaccination. The best way to increase these rates is by helping individuals who are hesitant about getting vaccinated to change their mindset and become more accepting of vaccines. | X | X | Within the healthcare system, pharmacists should be highlighted to address vaccine hesitancy in patients. Vaccine hesitancy is handled in the pharmacy through involvement of vaccines. | |||||

| Wanigaratne et al., 2023 [22] | Not mentioned in the study | Migrants have demonstrated repeating themes within vaccination that includes access, affordability, awareness, acceptance, and activation. Repeating themes in vaccination also include feeling a lack of trust towards healthcare and the government. | X | To increase participation of the bivalent COVID-19 vaccine, the healthcare system must gain the trust of the migrant communities. | ||||||

| Painter et al., 2019 [37] | Not mentioned in the study | In the study, participants demonstrated a lack of hesitation for vaccination amongst their daughters. Although there was little to no vaccine hesitancy, there was a clear lack of knowledge regarding general vaccines and history of immunization. | X | X | X | Amongst the repeating themes in the barriers of increasing vaccination rates, this study recommended finding ways to increase accessibility and education for vaccines. This would encourage the uninsured Latin American families to obtain their vaccines. | ||||

| Zhang et al., 2021 [25] | A total of 29.7% had no plans on receiving COVID-19 vaccines | In this study, the authors surveyed refugees and discovered the participants held high acceptance towards COVID-19 vaccines. | X | X | To continue a strong acceptance in vaccines, the government and healthcare system must work with refugees to ensure vaccines remain accessible. | |||||

| McFadden et al., 2022 [23] | Not mentioned in the study | This study attempted to understand the reason behind vaccine hesitancy. In this study, participants explained the reasons for uncertainty and would prefer to hold off to see how other patients may react to the vaccines. | X | X | X | This study recommends increasing accessibility to education regarding how vaccines are developed and explaining the importance behind vaccines to these hesitant patients. | ||||

| Sudhinaraset, Nwankwo, and Choi 2022 [29] | Not mentioned in the study | This research suggests that immigration enforcement negatively affects health behaviors. | X | Enforcement tactics like surveillance, profiling, and deportation might target undocumented men more, leading to mistrust and fear of public health efforts. Asian undocumented individuals may be less accepting due to the increased anti-Asian attacks during the pandemic, fueled by rhetoric and policies from US government officials. | ||||||

| Malone et al., 2022 [33] | Not mentioned in the study | Elderly patients are often found to have a lack of access to vaccines. The lack of accessibility could be due to reasons such as transportation. | X | X | X | By addressing these concerns, elderly patients have a higher chance of becoming vaccinated. These concerns can be addressed by creating vaccination sites in greater regions to ensure accessibility in all communities. | ||||

| Ogunbajo and Ojikutu 2022 [24] | A total of 43% would not get the COVID-19 vaccine immediately or at all | Black immigrants in the US have demonstrated increased vaccine hesitancy and tend to deny vaccinations. Some factors that contribute to vaccine hesitancy include less education, females, and working in healthcare settings. | X | X | X | Interventions to address vaccine hesitancy must address cultural barriers that immigrant populations face. One example of intervention could be offering education opportunities in healthcare. | ||||

| Allen et al., 2022 [38] | A total of 29.2% were unsure or would not get vaccinated | In this study, participants demonstrated a lack of vaccine hesitancy when holding high confidence in healthcare providers and accepting the gravity of the pandemic. | X | X | X | To address vaccine hesitancy in Brazilian immigrants, education and emphasis of the severity of the pandemic is crucial. Information can be shared within the communities through Media channels within the local cultural context. | ||||

| Daniels et al., 2022 [31] | Not mentioned in the study | In this study, the participants demonstrated potential willingness to alter vaccine hesitancy with higher accessibility to resources in healthcare. | X | X | X | X | Supporting a policy to ensure federal funding for health services and following ACIP guidelines for recommended immunizations will boost vaccination rates for RIM. | |||

| Kirchoff et al., 2023 [26] | A total of 32.5% | In this study, participants displayed vaccine hesitancy through themes of mistrust in the healthcare system and the safety behind vaccinations | X | X | X | To decrease vaccine hesitancy, the government and healthcare system must promote unity to the immigrant communities. | ||||

| Valero-Martínez et al., 2023 [28] | Not mentioned in the study | This study observed immigrant participants in the elderly community. Participants exhibited vaccine hesitancy through themes such as mistrust, safety concerns, and systemic barriers. | X | X | To tackle these barriers, the government and healthcare system is encouraged to release more information and education regarding vaccines. Rollout programs would also be effective in addressing safety concerns. | |||||

| Sharp et al., 2024 [27] | A total of 24% unvaccinated 5% partially vaccinated | Positive attitudes towards the vaccine stemmed from personal or community protection. The younger generation held higher reluctancy in getting the vaccine. In the African immigrant population, patients did not trust the government or healthcare system, due to the history of mistreatment in research and healthcare systems. | X | X | X | Plans and focus groups should be set in place to target the younger generations to build trust regarding vaccine hesitancy. | ||||

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned

4.2. Barriers to Childhood Vaccinations

4.3. Global Perspectives of Vaccine Hesitancy

4.4. Applications in Pharmacy

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. Explaining the Immunization Agenda 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/strategies/ia2030/explaining-the-immunization-agenda-2030 (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Overview—European Commission; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/vaccination/overview_en (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- The Victorian Government Department of Health. New Measles Cases in Victoria; The Victorian Government Department of Health: Victoria, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/health-alerts/new-measles-cases-in-victoria (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Local Government Association. Confidence, Complacency, Convenience Model of Vaccine Hesitancy|Local Government Association; Local Government Association: Westminster, London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/coronavirus-information-councils/covid-19-service-information/covid-19-vaccinations/behavioural-insights/resources/3Cmodel-vaccine-hesitancy (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- National Geographic. United States Immigration; National Geographic: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/resource-library-united-states-immigration/ (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Save the Children. Asylum Seekers, Migrants and Immigrants and Refugees Save the Children; Save the Children: Fairfield, CT, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.savethechildren.org/us/charity-stories/child-refugees-migrants-asylum-seekers-immigrants-definition (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- International Rescue Committee. Migrants, Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and Immigrants: What’s the Difference? International Rescue Committee: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.rescue.org/article/migrants-asylum-seekers-refugees-and-immigrants-whats-difference (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Refugee and Migrant Health—Global; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/refugee-and-migrant-health (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Castañeda, H.; Holmes, S.M.; Madrigal, D.S.; Young, M.E.; Beyeler, N.; Quesada, J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svallfors, S.; Larsson, E.C.; Puranen, B.; Ekström, A.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among first-generation immigrants living in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, S.E.; Deal, A.; Cheng, C.; Crawshaw, A.; Orcutt, M.; Vandrevala, T.F.; Norredam, M.; Carballo, M.; Ciftci, Y.; Requena-Méndez, A.; et al. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 among migrant populations in high-income countries: A systematic review. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, M.; Mateo-Urdiales, A.; Andrianou, X.; Bella, A.; Del Manso, M.; Bellino, S.; Rota, M.C.; Boros, S.; Vescio, M.F.; D’Ancona, F.P.; et al. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 cases in non-Italian nationals notified to the Italian surveillance system. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklists—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Oxford, UK, 2024; Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktürk, Z.; Linde, K.; Hapfelmeier, A.; Kunisch, R.; Schneider, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in people with migratory backgrounds: A cross-sectional study among Turkish- and German-speaking citizens in Munich. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penot, P.; Chateauneuf, J.; Auperin, I.; Cordell, H.; Letembet, V.-A.; Bottero, J.; Cailhol, J. Socioeconomic impact of the COVID-19 crisis and early perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines among immigrant and nonimmigrant people living with HIV followed up in public hospitals in Seine-Saint-Denis, France. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0276038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanigaratne, S.; Lu, H.; Gandhi, S.; Shetty, J.; Stukel, T.A.; Piché-Renaud, P.-P.; Brandenberger, J.; Abdi, S.; Guttmann, A. COVID-19 vaccine equity: A retrospective population-based cohort study examining primary series and first booster coverage among persons with a history of immigration and other residents of Ontario, Canada. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1232507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, S.M.; Demeke, J.; Dada, D.; Wilton, L.; Wang, M.; Vlahov, D.; Nelson, L.E. Confidence and Hesitancy During the Early Roll-out of COVID-19 Vaccines Among Black, Hispanic, and Undocumented Immigrant Communities: A Review. J. Urban Health 2022, 99, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunbajo, A.; Ojikutu, B.O. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccines among Black immigrants living in the United States. Vaccine X 2022, 12, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Gurung, A.; Anglewicz, P.; Subedi, P.; Payton, C.; Ali, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Haider, M.; Hamidi, N.; Atem, J.; et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine Among Refugees in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchoff, C.; Penn, A.; Wang, W.; Babino, R.; De La Rosa, M.; Cano, M.A.; Sanchez, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Latino/a Immigrants: The Role of Collective Responsibility and Confidence. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2023, 25, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharp, M.; Lozano, P.; Southworth, A.; Peters, A.; Lam, H.; Randal, F.T.; Quinn, M.; Kim, K.E. Mixed methods approach to understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among immigrants in the Chicago. Vaccine 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero-Martínez, C.; Martínez-Rivera, C.; Zhen-Duan, J.; Fukuda, M.; Alegría, M. Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: A Qualitative Study of Mostly Immigrant Racial/Ethnic Minority Older Adults. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhinaraset, M.; Nwankwo, E.; Choi, H.Y. Immigration enforcement exposures and COVID-19 vaccine intentions among undocumented immigrants in California. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 27, 101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S. COVID-19 Pandemic and Im/migrants’ Elevated Health Concerns in Canada: Vaccine Hesitancy, Anticipated Stigma, and Risk Perception of Accessing Care. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, D.; Imdad, A.; Buscemi-Kimmins, T.; Vitale, D.; Rani, U.; Darabaner, E.; Shaw, A.; Shaw, J. Vaccine hesitancy in the refugee, immigrant, and migrant population in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Vaccince Immunother. 2022, 18, 2131168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajgain, B.B.; Jackson, J.; Aghajafari, F.; Bolo, C.; Santana, M.J. Immigrant Healthcare Experiences and Impacts During COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Study in Alberta, Canada. J. Patient. Exp. 2022, 9, 23743735221112707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, B.; Kim, E.; Jennings, R.; Pacheco, R.A.; Kieu, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution in a Community With Large Numbers of Immigrants and Refugees. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratoberdha, D.; Gobis, B.; Ziemczonek, A.; Yuen, J.; Giang, A.; Zed, P.J. Barriers to adult vaccination in Canada: A qualitative systematic review. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott) 2022, 155, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibrik, L.; Huang, A.; Wong, V.; Novak Lauscher, H.; Choo, Q.; Yoshida, E.M.; Ho, K. Let’s Talk About B: Barriers to Hepatitis B Screening and Vaccination Among Asian and South Asian Immigrants in British Columbia. J. Racial. Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 5, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, E.; Ramsden, V.; Olatunbosun, O.; Williams-Roberts, H. Knowledge, Attitudes and Barriers to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Uptake Among an Immigrant and Refugee Catch-Up Group in a Western Canadian Province. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1424–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, J.E.; Viana De OMesquita, S.; Jimenez, L.; Avila, A.A.; Sutter, C.J.; Sutter, R. Vaccine-related attitudes and decision-making among uninsured, Latin American immigrant mothers of adolescent daughters: A qualitative study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.D.; Priebe Rocha, L.; Rose, R.; Hoch, A.; Porteny, T.; Fernandes, A.; Galvão, H. Intention to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine among Brazilian immigrant women in the U.S. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holz, M.; Mayerl, J.; Andersen, H.; Maskow, B. How Does Migration Background Affect COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions? A Complex Relationship Between General Attitudes, Religiosity, Acculturation and Fears of Infection. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 854146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, P.; Gele, A.; Aambø, A.; Qureshi, S.A.; Sheikh, N.; Vedaa, Ø.; Indseth, T. Lowering COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among immigrants in Norway: Opinions and suggestions by immigrants. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 994125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, A.B.; Hansen, B.; Kim, Y.I.; Scarinci, I.C. Latinx Immigrant Mothers’ Perceived Self-Efficacy and Intentions Regarding Human Papillomavirus Vaccination of Their Daughters. Womens Health Issues 2022, 32, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajos, N.; Spire, A.; Silberzan, L.; EPICOV study group. The social specificities of hostility toward vaccination against COVID-19 in France. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarajan, A.; Moslimani, M.; Lopez, M.H. Key Facts about Recent Trends in Global Migration; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/12/16/key-facts-about-recent-trends-in-global-migration/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Harapan, H.; Anwar, S.; Yufika, A.; Sharun, K.; Gachabayov, M.; Fahriani, M.; Husnah, M.; Raad, R.; Abdalla, R.Y.; Adam, R.Y.; et al. Vaccine hesitancy among communities in ten countries in Asia, Africa, and South America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pathog. Glob. Health 2022, 116, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.G.; Lasco, G.; David, C.C. Fear, mistrust, and vaccine hesitancy: Narratives of the dengue vaccine controversy in the Philippines. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4964–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, H.; Lawton, A.; Hossain, S.; Mustafa, A.H.M.G.; Razzaque, A.; Kuhn, R. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Temporary Foreign Workers from Bangladesh. Health Syst. Reform. 2021, 7, e1991550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintunde, T.Y.; Chen, J.K.; Ibrahim, E.; Isangha, S.O.; Sayibu, M.; Musa, T.H. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine uptake among foreign migrants in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achangwa, C.; Lee, T.J.; Lee, M.S. Acceptance of the COVID-19 Vaccine by Foreigners in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B.J.; Murphy, S.; Mau, V.; Bryant, R.; O’Donnell, M.; McMahon, M.; Nickerson, A. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst refugees in Australia. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1997173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tankwanchi, A.S.; Bowman, B.; Garrison, M.; Larson, H.; Wiysonge, C.S. Vaccine hesitancy in migrant communities: A rapid review of latest evidence. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 71, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankwanchi, A.S.; Jaca, A.; Ndlambe, A.M.; Zantsi, Z.P.; Bowman, B.; Garrison, M.M.; Larson, H.J.; Vermund, S.H.; Wiysonge, C.S. Non-COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among migrant populations worldwide: A scoping review of the literature, 2000–2020. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 1269–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, A.; Crawshaw, A.F.; Carter, J.; Knights, F.; Iwami, M.; Darwish, M.; Hossain, R.; Immordino, P.; Kaojaroen, K.; Severoni, S.; et al. Defining drivers of under-immunization and vaccine hesitancy in refugee and migrant populations. J. Travel. Med. 2023, 30, taad084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrie, Y.C. The Role of the Pharmacist in Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy; Newark, US Pharmacist: Lyndhurst, NJ, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/the-role-of-the-pharmacist-in-overcoming-vaccine-hesitancy (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Kiptoo, J.; Isiiko, J.; Yadesa, T.M.; Rhodah, T.; Alele, P.E.; Mulogo, E.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Assessing the prevalence, predictors, and effectiveness of a community pharmacy based counseling intervention. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social Determinants of Health at CDC|About; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- American Psychological Association. Ethnic and Racial Minorities & Socioeconomic Status; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/minorities (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Impact of Racism on Our Nation’s Health|Minority Health|CDC; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/racism-disparities/impact-of-racism.html (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- World Health Organization. Tackling Structural Racism and Ethnicity-Based Discrimination in Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/tackling-structural-racism-and-ethnicity-based-discrimination-in-health (accessed on 2 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, J.; Lao, C.; Dino, G.; Donyaei, R.; Lui, R.; Huynh, J. Vaccine Hesitancy among Immigrants: A Narrative Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned. Vaccines 2024, 12, 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12050445

Wong J, Lao C, Dino G, Donyaei R, Lui R, Huynh J. Vaccine Hesitancy among Immigrants: A Narrative Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned. Vaccines. 2024; 12(5):445. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12050445

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Jason, Crystal Lao, Giancarlo Dino, Roujina Donyaei, Rachel Lui, and Jennie Huynh. 2024. "Vaccine Hesitancy among Immigrants: A Narrative Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned" Vaccines 12, no. 5: 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12050445

APA StyleWong, J., Lao, C., Dino, G., Donyaei, R., Lui, R., & Huynh, J. (2024). Vaccine Hesitancy among Immigrants: A Narrative Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned. Vaccines, 12(5), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12050445