Messaging to Reduce Booster Hesitancy among the Fully Vaccinated

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Design

3. Results

- Increase intentions to get the booster;

- Increase targeted perceptions (safety/effectiveness);

- Reduce contributors to booster hesitancy.

3.1. Booster Intention

3.2. Perceptions of Effectiveness and Safety

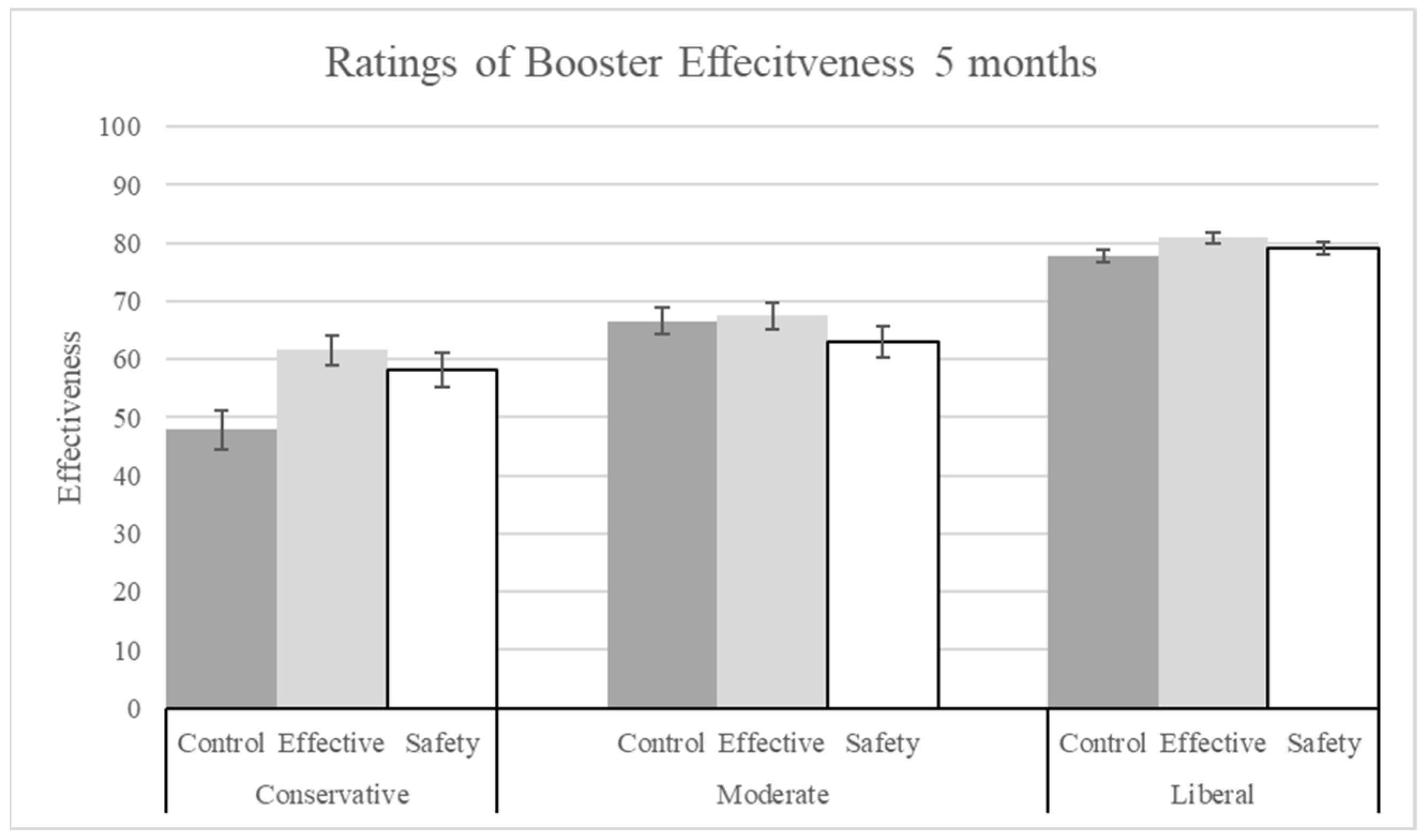

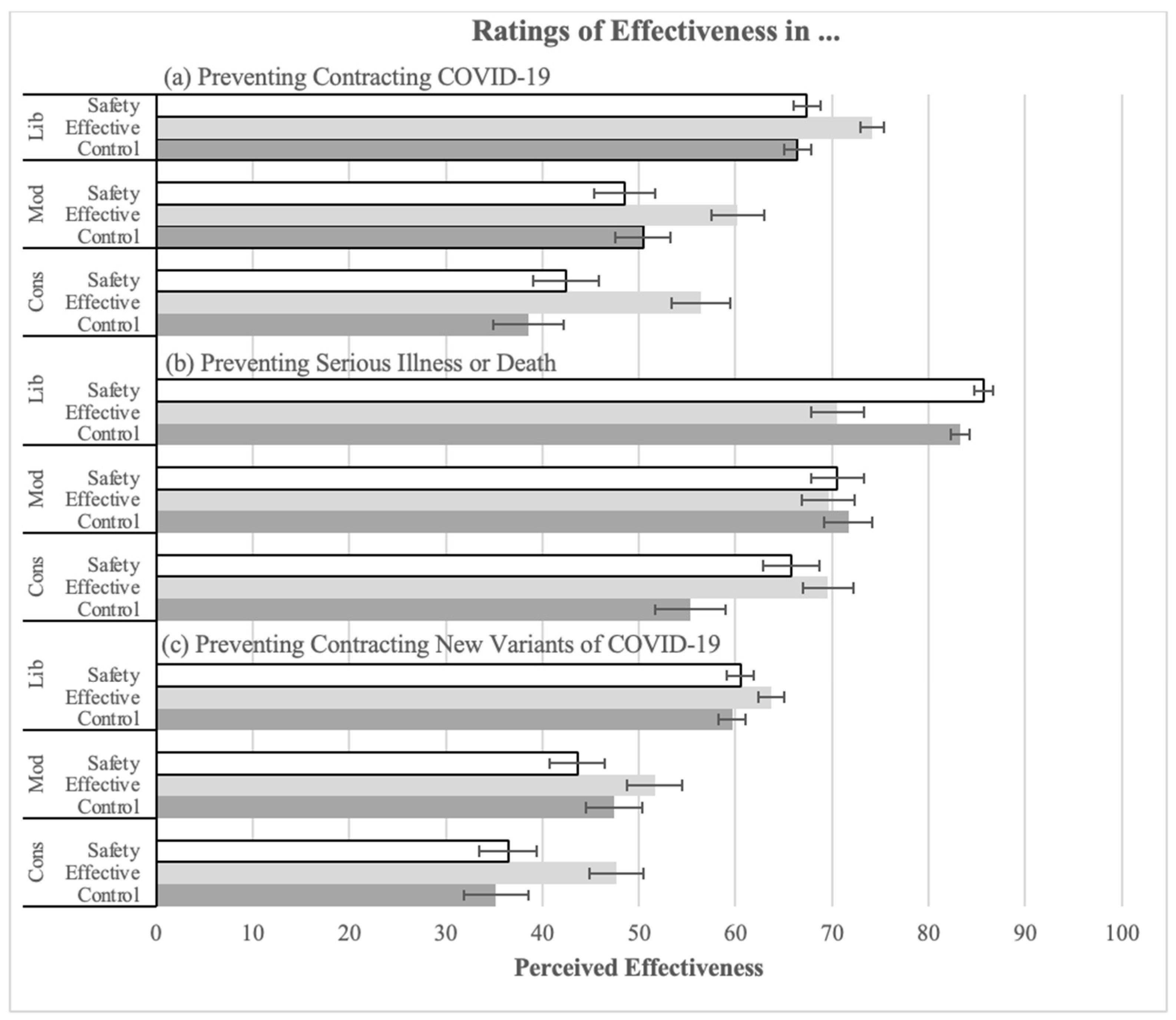

3.2.1. Perceived Effectiveness of the Booster

3.2.2. Perceived Safety of the Booster

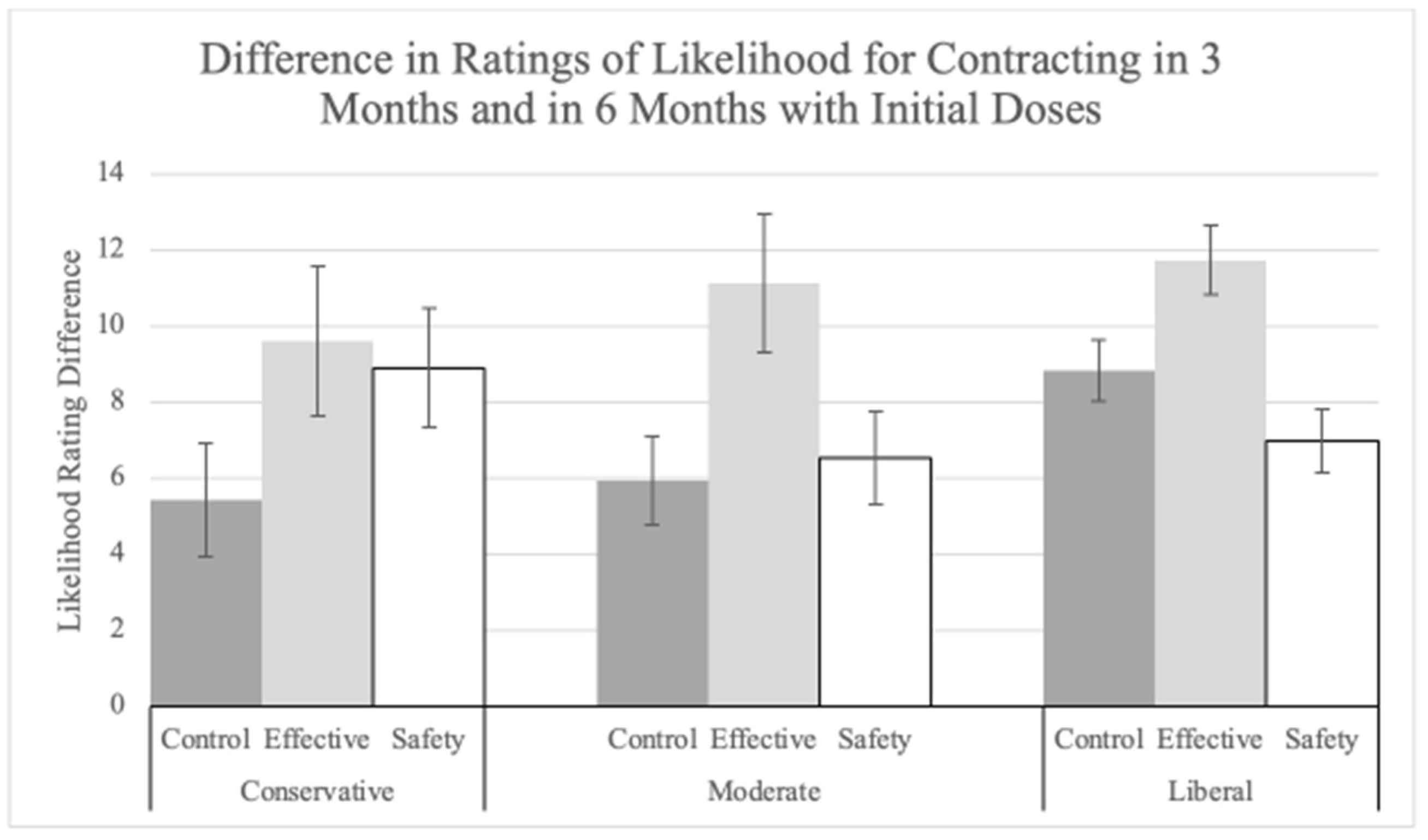

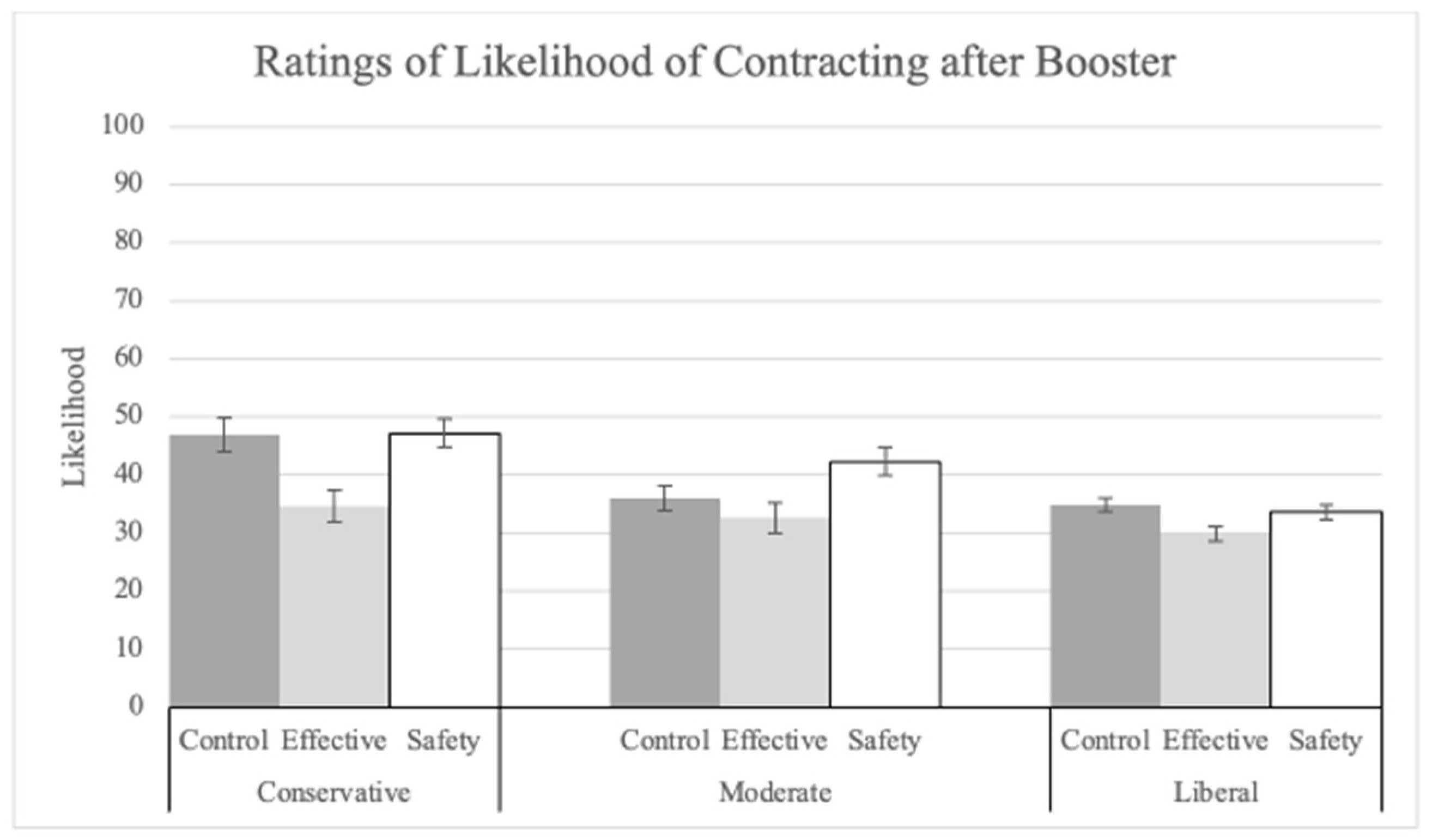

3.3. Contributors to Booster Hesitancy

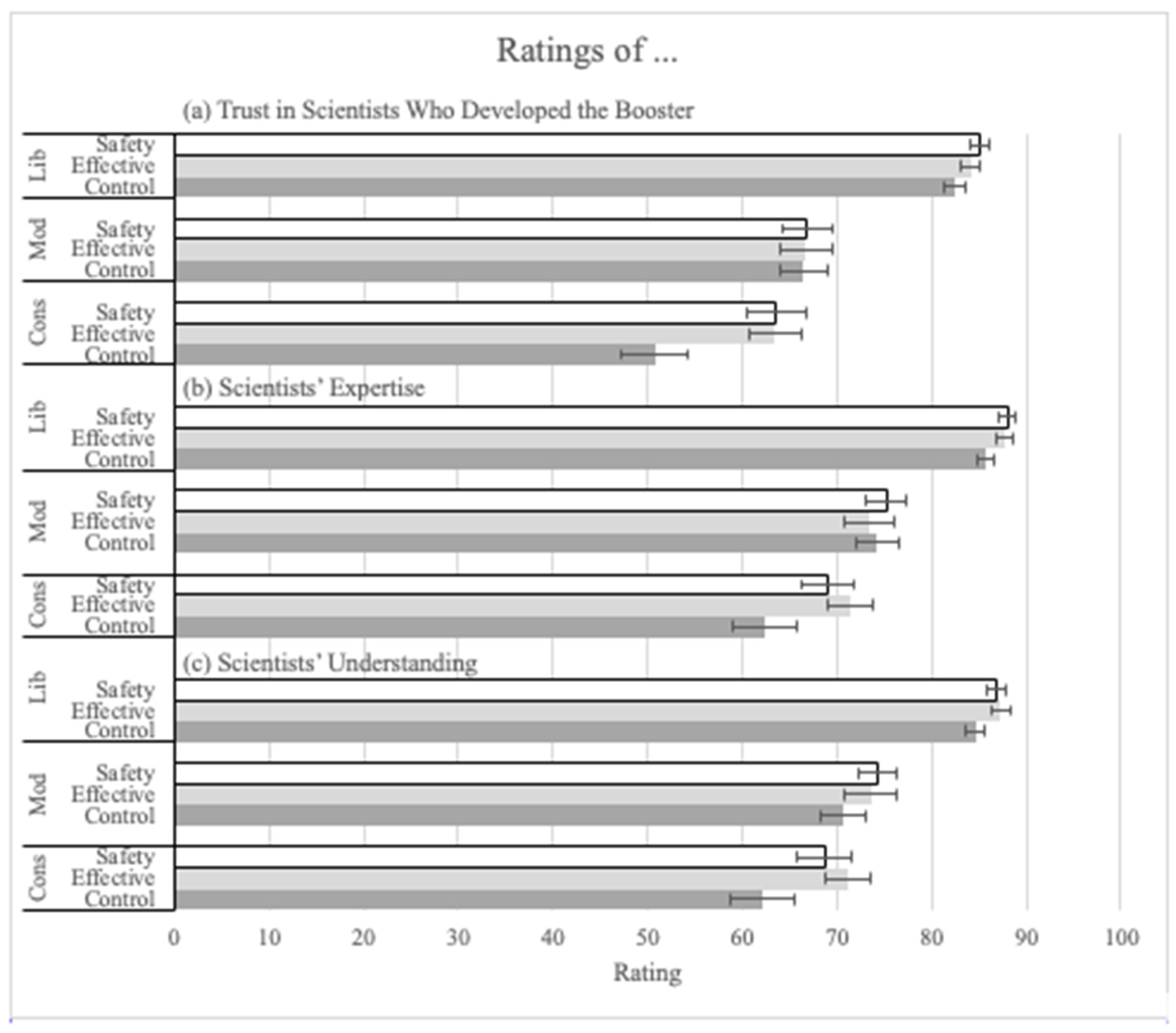

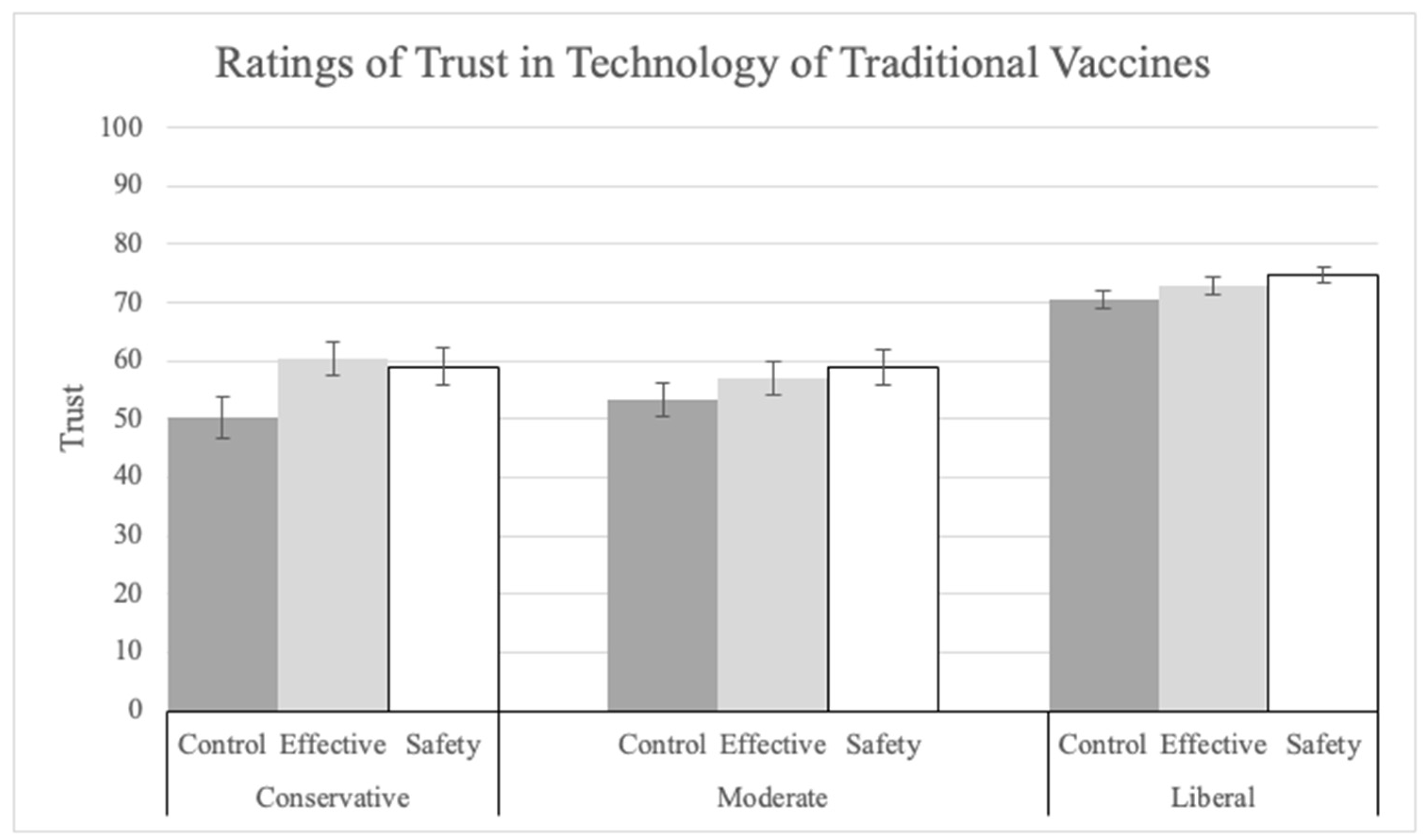

Trust in Booster Science and Scientists

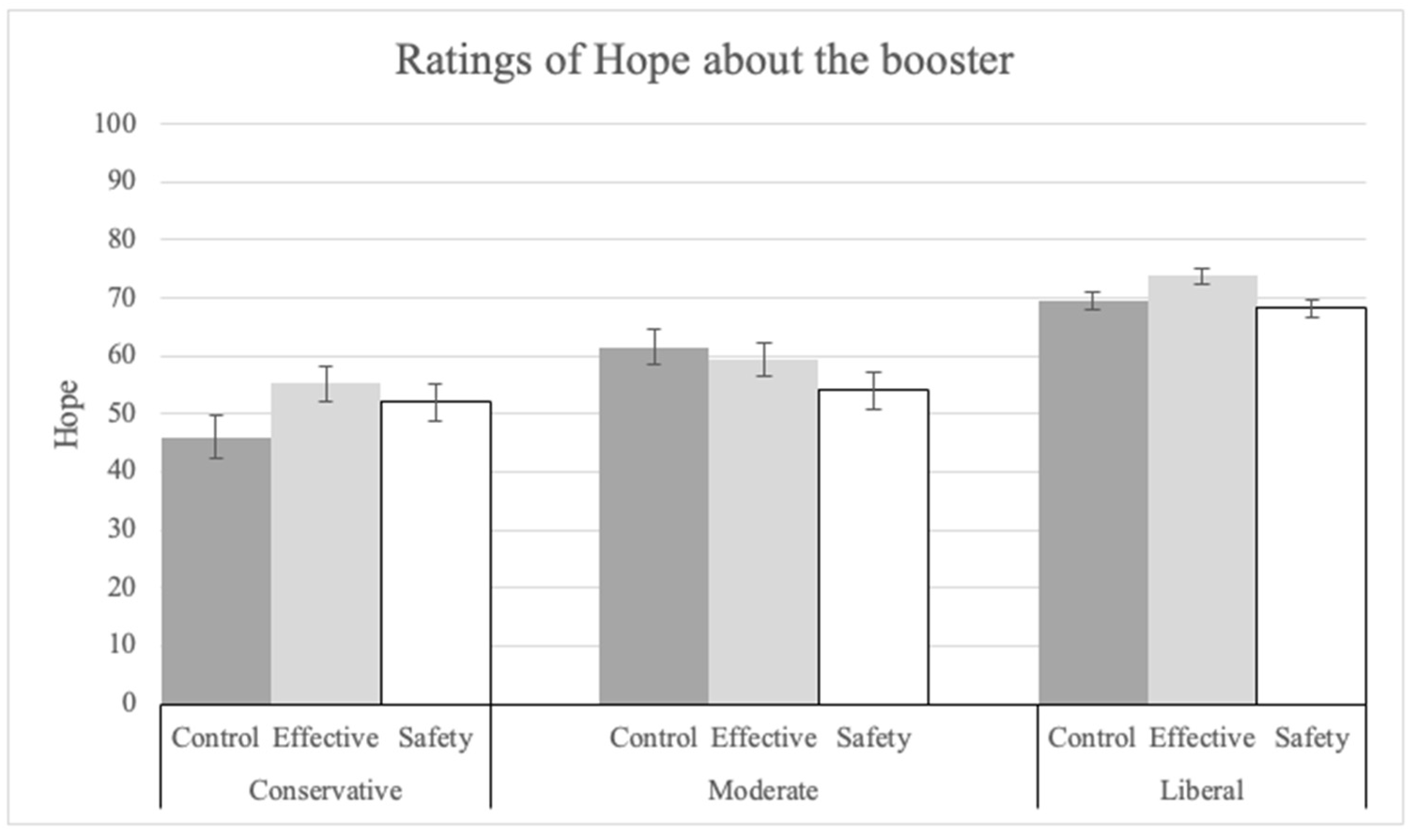

3.4. Emotion toward the Booster

3.5. Omission Bias Question

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Demographic Data

| US 2020 | This Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Percentage | N | Percentage |

| 18–49 | 77.9% | 1162 | 82% |

| 50+ | ~31% | 247 | 18% |

| US 2021 | This Experiment | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Percentage | Percentage |

| Lower than bachelor’s | 67.10% | 43% |

| Bachelor’s or higher | 32.90% | 56% |

| US 2021 | This Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race and Ethnicity | Percentage | N | Percentage |

| African American, Black, African, Caribbean | 13.40% | 115 | 8% |

| Asian American, Asian, Pacific Islander | 5.90% | 139 | 10% |

| Bi-racial, multi-racial | 2.8% | 51 | 4% |

| European American, White, Anglo, Caucasian | 60.1% | 979 | 69% |

| Hispanic American, Latina(o), Chicana(o) | 18.50% | 104 | 7% |

| Middle Eastern/North African | NA | 9 | 1% |

| Native American, American Indian | 1.30% | 3 | 0% |

| Other | NA | 1 | 0% |

| Prefer not to answer | NA | 8 | 1% |

| US 2021 | This Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Political Ideology | Percentage | N | Percentage |

| Conservative | 37% | 227 | 16% |

| Moderate | 36% | 270 | 19% |

| Liberal | 25% | 912 | 65% |

| Variables | Levels | Estimate | Odds Ratio | p-Value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | |||||

| Age | 0.009 | 1.09 | 0.09 | ||

| Categorical | |||||

| Gender | Female | Reference | 642 | ||

| Male | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 738 | |

| Other | 0.52 | 1.68 | 0.25 | 29 | |

| Education | Bachelor’s degree | Reference | 584 | ||

| No high school | 14.97 | 3,187,205 | 0.96 | 6 | |

| High school diploma | −0.22 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 179 | |

| Associate’s degree | 0.08 | 1.08 | 0.57 | 427 | |

| Master’s degree | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.21 | 171 | |

| Doctorate degree | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 38 | |

| Prefer not to answer | −0.86 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 4 | |

| Ethnicity | White American | Reference | 979 | ||

| African American | −0.16 | 0.85 | 0.47 | 115 | |

| Asian American | −0.12 | 0.89 | 0.57 | 139 | |

| Bi-racial | −0.09 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 51 | |

| Hispanic American | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.91 | 104 | |

| Middle Eastern | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.93 | 9 | |

| Native American | 1.01 | 2.75 | 0.49 | 3 | |

| Other | −14.93 | <0.001 | 0.99 | 1 | |

| Prefer not to answer | −1.13 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 8 | |

| Annual income | Less than USD 10,000 | Reference | 65 | ||

| USD 10,000–USD 19,999 | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.74 | 81 | |

| USD 20,000–USD 29,999 | −0.08 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 127 | |

| USD 30,000–USD 39,999 | 0.31 | 1.37 | 0.34 | 133 | |

| USD 40,000–USD 49,999 | 0.25 | 1.28 | 0.46 | 128 | |

| USD 50,000–USD 59,999 | −0.09 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 141 | |

| USD 60,000–USD 69,999 | −0.13 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 110 | |

| USD 70,000–USD 79,999 | −0.29 | 0.75 | 0.41 | 100 | |

| USD 80,000–USD 89,999 | 0.26 | 1.30 | 0.47 | 93 | |

| USD 90,000–USD 99,999 | 0.04 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 90 | |

| USD 100,000–USD 149,999 | 0.09 | 1.10 | 0.77 | 191 | |

| USD 150,000 or more | 0.16 | 1.18 | 0.64 | 124 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.67 | 26 | |

| Political ideology | Conservative | Reference | 466 | ||

| Liberal | 2.02 | 7.55 | <0.001 | 471 | |

| Moderate | 0.7 | 2.02 | <0.001 | 472 | |

| Condition | Control | Reference | 227 | ||

| Effectiveness | 0.45 | 1.57 | 0.002 | 912 | |

| Safety | 0.54 | 1.72 | <0.001 | 270 |

Appendix B. Experiment Questions

| Question Number | Question Wording |

| 1 | How likely do you think it is that you would become infected with COVID-19 in the next 6 months? |

| 2 | If you become infected with COVID-19, how likely do you think it is that you would die from COVID-19 |

| 3 | If you become infected with COVID-19, how likely do you think it is that you would be hospitalized? |

| 4 | If you become infected with COVID-19, how likely do you think it is that you would experience “long COVID-19” symptoms? |

| 5 | When thinking about becoming infected with COVID-19, how much fear do you feel? |

| 6 | When thinking about becoming infected with COVID-19, how much anxiety do you feel? |

| 7 | Choose the statement that best describes your status with regard to the mRNA COVID-19 booster shots.

|

| 8 | If you have not received all the mRNA COVID-19 booster shots for which you are eligible, choose the statement that best describes your situation or intentions.

|

| 9 | How safe do you think the mRNA COVID-19 booster shots are? [VAS endpoints “Not at all safe” to” Completely safe”] |

| 10 | How effective do you think the mRNA COVID-19 booster shots are in preventing you from contracting COVID-19 if you were exposed to it? [VAS endpoints “Not at all effective” to” Completely effective”] |

| 11 | How effective do you think the mRNA COVID-19 booster shots are in preventing severe illness or death if you were exposed to COVID-19 and contracted it? [VAS endpoints “Not at all effective” to” Completely effective”] |

| 12 | How effective do you think the mRNA COVID-19 booster shots are in preventing you from contracting COVID-19 if you were exposed to one of the new variants of COVID-19? [VAS endpoints “Not at all effective” to” Completely effective”] |

| 13 | How much do you trust the information about COVID-19 that is provided above? NOTE: This question is NOT shown to those participants in the no-information control group. [VAS endpoints “Not at all” to” Completely”] |

| 14 | How much do you trust the scientists who developed and tested mRNA COVID-19 vaccine boosters? [VAS endpoints “Not at all” to” Completely Trust”] |

| 15 | Thinking about the scientists who developed and tested the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine boosters: How much of the necessary expertise do they have to develop a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine booster? [VAS endpoints “None” to “All”] |

| 16 | Thinking about the scientists who created and tested the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine boosters: How well do they understand the issues relevant to developing a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine booster? [VAS endpoints “Not at all” to” Completely”] |

| 17 | Thinking about the scientists who created and tested the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines: To what extent do you think they compromised the testing of the COVID-19 vaccine boosters (cut corners) to make it quickly available? [VAS endpoints “Not at all” to” Completely”] |

| 18 | How concerned are you about the safety and effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 booster shots? [VAS endpoints “Not at all concerned” to” Extremely concerned”] |

| 19 | How concerned are you about any possible short-term side effects of mRNA COVID-19 booster shots? [VAS endpoints “Not at all concerned” to” Extremely concerned”] |

| 20 | How concerned are you about any possible long-term side effects of mRNA COVID-19 booster shots? [VAS endpoints “Not at all concerned” to” Extremely concerned”] |

| 21 | When thinking about the safety and effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 booster shots, how much fear do you feel? [VAS endpoints “None” to” A Lot”] |

| 22 | When thinking about the safety and effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 booster shots, how much anxiety do you feel? [VAS endpoints “None” to” A Lot”] |

| 23 | When thinking about the safety and effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 booster, how much hope do you feel? [VAS endpoints “None” to” A Lot”] |

| 24 | How much do you trust the technology of mRNA vaccines like Pfizer and Moderna? [VAS endpoints “Not at all” to “Completely”] |

| 25 | How much do you trust the technology of conventional vaccines like Johnson & Johnson? [VAS endpoints “Not at all” to “Completely”] |

| 26 | In which situation do you think you will feel more regret?

|

| 27 | How likely do you think it is that you would become infected with COVID-19 in the first 3 months after being fully vaccinated with the initial doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (but not boosted)? [VAS endpoints “Impossible” to “Certain”] |

| 28 | How likely do you think it is that you would become infected with COVID-19 6 months after being fully vaccinated with the initial doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (but not boosted)? [VAS endpoints “Impossible” to “Certain”] |

| 29 | What do you think is the effectiveness of the mRNA vaccines for the first 5 months after vaccination? [VAS endpoints “Not effective all” to “Extremely Effective”] |

| 30 | How likely do you think it is that you would become infected with COVID-19 after being fully vaccinated with the initial doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and boosted? [VAS endpoints “Impossible” to “Certain”] |

| 31 | Gender (Options: Male, Female, Other) |

| 32 | Age (in years): numeric |

| 33 | What is the highest degree or level of school that you have completed? Please select ONE option.

|

| 34 | Please select ALL that apply to you.

|

| 35 | Please indicate the answer that includes your entire household income in (previous year) before taxes. Select one from:

|

| 36 | Political ideology: In general, do you think of yourself as:

|

| 37 | We just want to make sure you are paying attention. This study is about COVID-19, but we want to you choose Ebola for this question.

|

Appendix C. Understanding Effectiveness Explanation

Appendix D. Analyses on Trust in Explanations

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-a). COVID Data Tracker. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_weeklydeaths_select_00 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.S.; Yu, L.M.; Freeman, J.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Shanyinde, M.; Harris, V.; Waite, F.; Lambe, S.; et al. Effects of different types of written vaccination information on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the U.K. (OCEANS-III): A single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e416–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.S.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Jenner, L.; Petit, A.; Lewandowsky, S.; Vanderslott, S.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the U.K.: The Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3127–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tram, K.H.; Saeed, S.; Bradley, C.; Fox, B.; Eshun-Wilson, I.; Mody, A.; Geng, E. Deliberation, dissent, and distrust: Understanding distinct drivers of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Milstein, A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021726118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, M.; Sylvester, S.; Callaghan, T.; Lunz-Trujillo, K. Encouraging COVID-19 vaccine uptake through effective health communication. Front. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 630133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, R.; Bolsen, T.; Kingsland, J.T. The effect of frames on COVID-19 vaccine resistance. Front. Political Sci. 2021, 3, 661257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyalasomayajula, S.; Dhawan, A.; Karattuthodi, M.S.; Thorakkattil, S.A.; Abdulsalim, S.; Elnaem, M.H.; Sridhar, S.; Unnikrishnan, M.K. A systematic review on sociodemographic, financial and psychological factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster hesitancy among adult population. Vaccines 2023, 11, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Groenewoud, R.; Rachor, G.S.; Asmundson, G.J.G. A proactive approach for managing COVID-19: The importance of understanding the motivational roots of vaccination hesitancy for SARS-CoV2. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 575950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; Qin, C.; Han, J.H.; Savelli, S.; Agrawal, N. Reducing Vaccine Hesitancy by Explaining Vaccine Science. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2023, 29, 489–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Y.; Mandel, M.; Bar-On, Y.M.; Bodenheimer, O.; Freedman, L.S.; Haas, E.; Milo, R.; Alroy-Preis, S.; Ash, N.; Huppert, A. Waning immunity of the BNT162b2 vaccine: A nationwide study from Israel. medRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-b). COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots. CDC COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/booster-shot.html?s_cid=11706:mix%20and%20match%20vaccines:sem.ga:p:RG:GM:gen:PTN:FY22 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior–a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanis, P.; Vraka, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Mariolis-Sapsakos, T.; Kaitelidou, D. First COVID-19 booster dose in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis of willingness and its predictors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluVaxView: 2022–2023 Influenza Vaccination Coverage Estimates. October 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-2223estimates.htm (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. Predicting COVID-19 booster vaccine intentions. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, L.; Kirzinger, A.; Lopes, L.; Sparks, G.; Kearney, A.; Stokes, M.; Brodie, M. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: May 2021. Kaiser Family Foundation. 28 May 2021. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-may-2021/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Neely, S.R.; Scacco, J.M. Receptiveness of American adults to COVID-19 vaccine boosters: A survey analysis. PEC Innov. 2022, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, T.; Moghtaderi, A.; Lueck, J.A.; Hotez, P.; Strych, U.; Dor, A.; Fowler, E.F.; Motta, M. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.B.; Bell, R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; LeClerc, J. Decisions with uncertainty: The glass half full. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; LeClerc, J. Climate projections and uncertainty communication. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2016, 8, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; Nemec, L.; Savelli, S. The benefits and challenges of predictive interval forecasts and verification graphics for end-users. Weather Clim. Soc. 2013, 27, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeClerc, J.; Joslyn, S. The cry wolf effect and weather-related decision making. Risk Anal. 2015, 35, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grounds, M.; Joslyn, S.; Otsuka, K. Probabilistic Interval Forecasts: An Individual Differences Approach to Understanding Forecast Communication. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017, 3932565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitta, A.; Goldberg, D.S. The significance of folklore for vaccine policy: Discarding the deficit model. Crit. Public Health 2017, 27, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, B.; Stornelli, J. Collective Health versus Individual Freedom: Goal Centrality and Political Identity Shape COVID-19 Prevention Behaviors. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2020, 7, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, S.; Prasad, S.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hswen, Y.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Zhang, B.; Kriner, D.L. Factors associated with US adults’ likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Nardi, A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health 2021, 194, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakanlar, A.; Trudel, R.; White, K. Political Ideology and the Perceived Impact of Coronavirus Prevention Behaviors for the Self and Others. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2020, 7, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.A.; Petty, R.E. Identity persuasion: An elaboration likelihood approach In Attitudes, Behavior, and Social Context: The Role of Norms and Group Membership; Terry, D.J., Hogg, M.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 171–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.S.; Nisbet, E.C. Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Commun. Res. 2012, 39, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; Demnitz, R. Explaining the How Long CO2 Stays in the Atmosphere: Does It Change Attitudes? J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2021, 27, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, J.; Ritov, I. Omission bias, individual differences, and normality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2004, 94, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Goodman, B. FDA Authorizes Updated COVID-19 Boosters from Pfizer and Moderna. CNN. 31 August 2022. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/31/health/fda-covid-vaccine-updated-booster-authorized/index.html (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Puranik, A.; Lenehan, P.J.; Silvert, E.; Niesen, M.J.M.; Corchado-Garcia, J.; O’horo, J.C.; Virk, A.; Swift, M.D.; Halamka, J.; Badley, A.D.; et al. Comparison of two highly-effective mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 during periods of Alpha and Delta variant prevalence. medRxiv 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hause, A.M.; Baggs, J.; Marquez, P.; Myers, T.R.; Su, J.R.; Blanc, P.G.; Baumblatt, J.A.G.; Woo, E.J.; Gee, J.; Shimabukuro, T.T.; et al. Safety monitoring of COVID-19 vaccine booster doses among adults-United States, September 22, 2021–February 6, 2022. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; Savelli, S.; Duarte, H.A.; Burgeno, J.; Qin, C.; Han, J.H.; Gulacsik, G. COVID-19: Risk perception, risk communication, and behavioral intentions. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2021, 27, 599–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.; Shevlin, M. (n.d.) MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit. (n.d.). Effect Size—Statswiki. Available online: https://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/effectSize (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Huhmann, B.A. Why some people are hesitant to receive COVID-19 boosters: A systematic review. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, P.D.; Weber, E.U. The interpretation of “likely” depends on the context, but “70%” is 70%—Right? The influence of associative processes on perceived certainty. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1999, 25, 1514–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budescu, D.V.; Bruderman, M. The relationship between the illusion of control and the desirability bias. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1995, 8, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barattucci, M.; Pagliaro, S.; Ballone, C.; Teresi, M.; Consoli, C.; Garofalo, A.; De Giorgio, A.; Ramaci, T. Trust in science as a possible mediator between different antecedents and COVID-19 booster vaccination intention: An integration of health belief model (HBM) and theory of planned behavior (TPB). Vaccines 2022, 10, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejko, K.L.; Myers, J.F.; Fukui, N.; Nelson, L.; Zhao, R.; Openshaw, J.; Watt, J.; Jain, S.; Lewnard, J.; Pry, J.M. Real-world uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among individuals expressing vaccine hesitancy: A registry-linkage study. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossowska, M.; Szwed, P.; Czarnek, G. Ideology shapes trust in scientists and attitudes towards vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2021, 24, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Dickau, L. Experimental evidence for the intention–behavior relationship in the physical activity domain: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Census Bureau. (n.d.). Estimates of the Total Resident Population and Resident Population Age 18 Years and Older for the United States, Regions, States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: July 1, 2020 (SC-EST2020-18+POP-RES) [Data Set]. US Census Bureau. Available online: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/tables/2010-2020/national/asrh/sc-est2020-18+pop-res.xlsx (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- US Census Bureau. Resident population of the United States by sex and age as of July 1, 2020 (in millions) [Graph]. In Statista. 23 July 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/241488/population-of-the-us-by-sex-and-age/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- US Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts: United States. US Census Bureau. 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045221 (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Saad, L. U.S. Political Ideology Steady; Conservatives, Moderates tie. Gallup.com. 24 January 2022. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/388988/political-ideology-steady-conservatives-moderates-tie.aspx (accessed on 1 June 2022).

| Condition | Explanation |

| No-Information Control | |

| Condition 1: Effectiveness | The following explanation refers to mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer and Moderna:

|

| Condition 2: Safety | The following explanation refers to mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer and Moderna: Of the side effects reported for over 12,591 booster shots of the vaccine, 99% were minor. They were comparable to those experienced with the second of the initial doses. Symptoms:

|

| Booster Intention | Explanations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No-Info Control | Effectiveness | Safety | |

| I would get an (or another if I already have one) mRNA COVID-19 booster shot as soon as possible | 214 (46%) | 262 (56%) | 269 (57%) |

| I would wait to get an (or another if I already have one) mRNA COVID-19 booster shot until there is more information | 130 (28%) | 92 (20%) | 78 (17%) |

| I don’t know | 36 (8%) | 35 (7%) | 36 (8%) |

| I would not get an (or another if I already have one) mRNA COVID-19 booster shot | 86 (18%) | 82 (17%) | 89 (19%) |

| Regret Option | Booster Yes | Booster No |

|---|---|---|

| More regret if boosted | 24 (3%) | 127 (19%) |

| More regret if un-boosted | 539 (72%) | 219 (33%) |

| Same regret | 100 (13%) | 220 (33%) |

| No regret | 82 (11%) | 98 (15%) |

| Regret Option | Control | Effectiveness | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|

| More regret if boosted | 55 (12%) | 49 (10%) | 47 (10%) |

| More regret if un-boosted | 245 (53%) | 251 (53%) | 262 (56%) |

| Same regret | 103 (22%) | 119 (25%) | 98 (21%) |

| No regret | 63 (14%) | 52 (11%) | 65 (14%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, C.; Joslyn, S.; Han, J.H.; Savelli, S.; Agrawal, N. Messaging to Reduce Booster Hesitancy among the Fully Vaccinated. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091066

Qin C, Joslyn S, Han JH, Savelli S, Agrawal N. Messaging to Reduce Booster Hesitancy among the Fully Vaccinated. Vaccines. 2024; 12(9):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091066

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Chao, Susan Joslyn, Jee Hoon Han, Sonia Savelli, and Nidhi Agrawal. 2024. "Messaging to Reduce Booster Hesitancy among the Fully Vaccinated" Vaccines 12, no. 9: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091066

APA StyleQin, C., Joslyn, S., Han, J. H., Savelli, S., & Agrawal, N. (2024). Messaging to Reduce Booster Hesitancy among the Fully Vaccinated. Vaccines, 12(9), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091066