Are HPV Vaccines Well Accepted among Parents of Adolescent Girls in China? Trends, Obstacles, and Practical Implications for Further Interventions: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

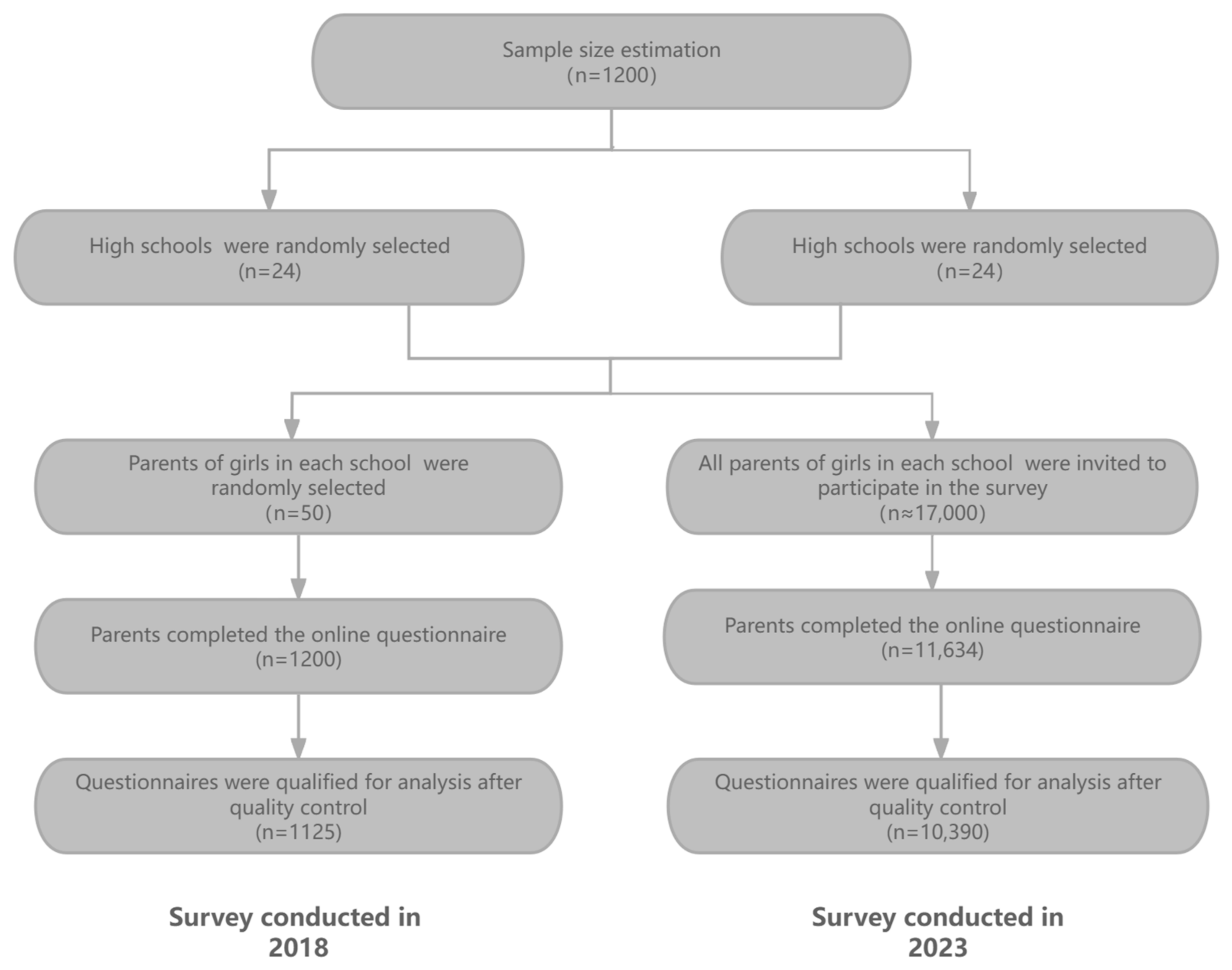

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size

2.2. Data Collection and Quality Control

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Characteristics

3.2. Changes in Parents’ Knowledge of CC- and HPV-Related Information

3.3. Changes in HPV Vaccination Coverage among Adolescent Girls

3.4. Reasons for Not Receiving HPV Vaccine among Adolescent Girls

3.5. Factors Associated with Uptake of the HPV Vaccine among Adolescent Girls

4. Discussion

4.1. Principle Findings

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPV | human papillomavirus |

| CC | cervical cancer |

| OR | odds ratio |

| AOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| 95%CI | 95% confidence interval |

References

- Simelela, P.N. WHO global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem: An opportunity to make it a disease of the past. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 152, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maomao, C.; Wanqing, C. GLOBOCAN 2020 Global cancer statistical data Read. Chin. Med. Front. J. (Electron. Ed.) 2021, 13, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, T.; Cui, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Piao, H. The prevalence, trends, and geo-graphical distribution of human papillomavirus infection in China: The pooled analysis of 1.7 million women. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 5373–5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccine and Immunology Branch of the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association. Expert consensus on immune prevention of cervical cancer and other papillomavirus related diseases. Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 53, 761–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M.; Ali, H.; Boily, M.C.; Yu, B.N. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019, 10197, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Medical Products Administration, Latest News on Drug Supervision. 2019. Available online: https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/zhuanti/cxylqx/cxypxx/20191231160701608.html (accessed on 23 January 2024). (In Chinese)

- National Medical Products Administration, Latest News on Drug Supervision. 2018. Available online: https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/zhuanti/cxylqx/cxypxx/20180429185501907.html (accessed on 23 January 2024). (In Chinese)

- Li, Z.; Fanghui, Z. Research progress on the application of preventive human papillomavirus vaccine. Chin. J. Oncol. 2018, 40, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Hu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, X. A nationwide post-marketing survey of knowledge, attitude and practice toward human papillomavirus vaccine in general population: Implications for vaccine roll-out in mainland China. Vaccine 2021, 39, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, Y.; Yao, D.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Q. A New Strategy for Cervical Cancer Prevention Among Chinese Women: How Much Do They Know and How Do They React Toward the HPV Immunization? J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 2021, 36, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuforo, B.; McGee-Avila, J.K.; Toler, L.; Xu, B.; Kohler, R.E.; Manne, S.; Tsui, J. Disparities in HPV vaccine knowledge and adolescent HPV vaccine uptake by parental nativity among diverse multiethnic parents in New Jersey. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, N.; Salamanca, D.L.C.I.; Taborga, E.; de Alba, A.F.; Cabeza, I.; Raba, R.M.; Marès, J.; Company, P.; Herrera, B.; Cotarelo, M. HPV knowledge and vaccine acceptability: A survey-based study among parents of adolescents (KAPPAS study). Infect. Agents Cancer 2022, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitaresmi, M.N.; Rozanti, N.M.; Simangunsong, L.B.; Wahab, A. Improvement of Parent’s Awareness, Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptability of HPV Vaccination After a Structured-educational Intervention. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milimo, M.M.; Daka, E.; Sikuyubs, L.; Nyirenda, J.; Ngoma, C. Knowledge and attitudes of Parents’Guardians towards uptake of Human Papopiloma Virus (HPV) vaccine in preventing cervical cancer among girls in Zambia. Afr. J. Med.Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, H.; Denford, S.; Audrey, S.; Finn, A.; Hajinur, H.; Hickman, M.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Mohamed, A.; Roderick, M.; Tucker, L.; et al. Information needs of ethnically diverse, vaccine-hesitant parents during decision-making about the HPV vaccine for their adolescent child: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2024, 24, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Di, N.; Tao, X. Knowledge, practice and attitude towards HPV vaccination among college students in Beijing, China. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, F.; Lian, G.; Li, S.; He, Q.; Li, T. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage and knowledge, perceptions and influencing factors among university students in Guangzhou, China. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 3603–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, A.Y.; Kwan, M.L.; Wong, Y.T.; Wong, A.K. The Uptake of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and its Associated factors among adolescents: A systematic review. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2017, 8, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Hu, N.H.; Thilly, N.; Derrough, T.; Sdona, E.; Claudot, F.; Pulcini, C.; Agrinier, N. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage, policies, and practical implementation across Europe. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1315–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, L.A.; Zimet, G.D.; McCaffery, K.J.; Ostini, R.; Waller, J. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination: An international comparison. Vaccine 2013, 31, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, T.; Lu, Q. Parental Acceptability of HPV Vaccination for Adolescent Daughters and Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Bozhou, China. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2020, 34, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkalash, S.H.; Alshamrani, F.A.; Alhashmi Alamer, E.H.; Alrabi, G.M.; Almazariqi, F.A.; Shaynawy, H.M. Parents’ Knowledge of and Attitude Toward the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e32679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarczyk, K.; Duszewska, A.; Drozd, S.; Majewski, S. Parents’ Knowledge and Attitude towards HPV and HPV Vaccination in Poland. Vaccines 2022, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihretie, G.N.; Liyeh, T.M.; Ayele, A.D.; Belay, H.G.; Yimer, T.S.; Miskr, A.D. Knowledge and willingness of parents towards child girl HPV vaccination in Debre Tabor Town, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbie, A.; Mekonnen, D.; Misgan, E.; Maier, M.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Abebe, T. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination and parents’ willingness to vaccinate their adolescents in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Agent. Cancer. 2023, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, X. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its determinants among teenagers and their parents in Zhejiang, China: An online cross-sectional study. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2023, 16, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatatbeh, M.; Albalas, S.; Khatatbeh, H.; Momani, W.; Melhem, O.; Al Omari, O.; Tarhini, Z.; A’aqoulah, A.; Al-Jubouri, M.; Nashwan, A.J.; et al. Children’s rates of COVID-19 vaccination as reported by parents, vaccine hesitancy, and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among children: A multi-country study from the eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboro, I.L.; Ogaji, D.S. Knowledge and uptake of human papillomavirus vaccine among female adolescents in Port Harcourt. A call for urgent intervention. Int. STD Res. Rev. 2023, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleemat, W.A.; Oluchi, J.K.-O.; Ifeoma, P.O.; Kofoworola, A.O. Parental willingness to vaccinate adolescent daughters against human papillomavirus for cervical cancer prevention in Western Nigeria. PAMJ 2020, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira-Rodrigues, A.; Flores, M.G.; Macedo, A.O.; Braga, L.A.C.; Vieira, C.M.; de Sousa-Lima, R.M.; de Andrade, D.A.P.; Machado, K.K.; Guimarães, A.P.G. HPV vaccination in Latin America: Coverage status, implementation challenges and strategies to overcome it. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 984449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampora, A.; Grossi, A.; Barbara, A.; Colamesta, V.; Causio, F.A.; Calabrò, G.E.; De Waure, C. Increasing HPV vaccination uptake among adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunade, K.S.; Sunmonu, O.; Osanyin, G.E.; Oluwole, A.A. Knowledge and Acceptability of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among Women Attending the Gynaecological Outpatient Clinics of a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos, Nigeria. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 2017, 8586459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherton, J.M.L.; Murray, S.L.; Hall, M.A.; Andrewartha, L.K.; Banks, C.A.; Meijer, D.; Pitcher, H.C.; Scully, M.M.; Molchanoff, L. Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage among female Australian adolescents: Success of the school-based approach. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Donovan, B.; Wand, H.; Read, T.R.H.; Regan, D.G.; Grulich, A.E.; Fairley, C.K.; Guy, R.J. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: National surveillance data. BMJ 2013, 346, f2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, C.R.; Wang, Z.Z.; Ren, Z.F.; Feng, X.X.; Ma, W.; Gao, X.H.; Zhang, R.; Brown, M.D.; Qiao, Y.L. Effect of a school-based educational intervention on HPV and HPV vaccine knowledge and willingness to be vaccinated among Chinese adolescents: A multi-center intervention follow-up study. Vaccine 2020, 38, 3665–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinhua Net. China’s First Domestic Hpv Vaccine Earns Who Prequalification. 2021. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-10/17/c_1310251153.htm (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- BBRTV. China’s First Domestic HPV Vaccine Shows 100 Pct Efficacy in Clinical Trial. 2021. Available online: http://www.bbrtv.com/2022/0831/768173.html (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- China Daily. Nation Plans to Launch Free HPV Vaccinations. 2021. Available online: http://ex.chinadaily.com.cn/exchange/partners/45/rss/channel/www/columns/2n8e04/stories/WS62cfcb51a310fd2b29e6c612.html,2021 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Gerend, M.A.; Madkins, K.; Phillips, G.I.I.; Mustanski, B. Predictors of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2016, 43, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Rosberger, Z.; Fisher, W.A.; Perez, S.; Stupiansky, N.W. Beliefs, behaviors and HPV vaccine: Correcting the myths and the misinformation. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.L.; Weiss, T.W.; Zimet, G.D.; Ma, L.; Good, M.B.; Vichnin, M.D. Predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among women aged 19–26: Importance of a physician’s recommendation. Vaccine 2011, 29, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laz, T.H.; Rahman, M.; Berenson, A.B. An update on human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among 11–17 year old girls in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3534–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylitalo, K.R.; Lee, H.; Mehta, N.K. Health care provider recommendation, human papillomavirus vaccination, and race/ethnicity in the US National Immunization Survey. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Survey in 2018 n (%) | Survey in 2023 n (%) | p * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 146 (13.0) | 1208 (11.6) | 0.181 |

| Female | 979 (87.0) | 9182 (88.4) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <40 | 330 (29.3) | 2753 (26.5) | 0.082 |

| 40–50 | 714 (63.5) | 6775 (65.2) | |

| 50–60 | 81 (7.2) | 862 (8.3) | |

| Education level | |||

| Primary or lower (<9 years) | 572 (50.8) | 5008 (48.2) | 0.234 |

| Secondary (9–12 years) | 302 (26.8) | 2909 (28.0) | |

| Postsecondary (>12 years) | 251 (22.3) | 2473 (23.8) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Government institution | 152 (13.5) | 1163 (11.2) | 0.029 |

| Business or service industry | 523 (46.5) | 4603 (44.3) | |

| Farmer | 136 (12.1) | 1403 (13.5) | |

| Stay-at-home mother/stay-at-home father/unemployed | 153 (13.6) | 1517 (14.6) | |

| Other (retired/business owner, etc.) | 161 (14.3) | 1704 (16.4) | |

| Annual household income (RMB) | |||

| <100,000 | 626 (55.6) | 5821 (56.0) | 0.969 |

| 100,000–200,000 | 339 (30.1) | 3100 (29.8) | |

| >200,000 | 160 (14.2) | 1469 (14.2) | |

| Immigration status | |||

| Resident | 882 (78.4) | 8208 (78.9) | 0.635 |

| Migrant from other counties of China | 243 (21.6) | 2182 (21.1) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 1026 (91.2) | 9487 (91.3) | 0.902 |

| Other (divorced/widowed/separated, etc.) | 99 (8.8) | 903 (8.7) |

| Variables | Survey in 2018 n (%) | Survey in 2023 n (%) | χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is cervical cancer one of the most common genital-system cancers among women worldwide? | ||||

| Yes | 984 (87.5) | 9602 (92.4) | 33.52 | <0.0001 |

| No | 141 (12.5) | 788 (7.6) | ||

| Do you agree that prevention of cervical cancer does not just concern older women? | ||||

| Yes | 530 (47.1) | 6378 (61.4) | 86.18 | <0.0001 |

| No | 595 (52.9) | 4012 (38.6) | ||

| Do you think HPV causes cervical cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 885 (78.7) | 8720 (83.9) | 20.3 | <0.0001 |

| No | 240 (21.3) | 1670 (16.1) | ||

| Is HPV primarily transmitted among humans through sex? | ||||

| Yes | 779 (69.2) | 7765 (74.7) | 15.99 | <0.0001 |

| No | 346 (30.8) | 2625 (25.3) | ||

| Are you aware that there are vaccines for cervical cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 611 (54.3) | 6532 (62.9) | 31.56 | <0.0001 |

| No | 514 (45.7) | 3858 (37.1) | ||

| Do you know the optimal age for HPV vaccination? | ||||

| Yes | 400 (35.6) | 5167 (49.7) | 81.67 | <0.0001 |

| No | 725 (64.4) | 5223 (50.3) | ||

| Would you approve of your children receiving HPV vaccination? * | ||||

| Yes | 398 (35.4) | 5881 (56.6) | 184.43 | <0.0001 |

| No | 727 (64.6) | 4509 (43.4) |

| Year | Number of Participants | Number of Participants Whose Children Received HPV Vaccine | HPV Vaccine Uptake (%) | χ2, p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 1125 | 50 | 4.4 | χ2 = 34.76, p < 0.0001 |

| 2023 | 10,390 | 1020 | 9.8 |

| Variables | HPV Vaccine Uptake (n, %) | OR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Gender of parents | ||||

| Female | 845 (9.2) | 8337 (90.8) | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 120 (9.9) | 1088 (90.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) |

| Age of parents (years) | ||||

| <40 | 153 (7.4) | 1910 (92.6) | 1 | 1 |

| 40–50 | 738 (10.3) | 6410 (89.7) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) * | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) *** |

| >50 | 129 (10.9) | 1050 (89.1) | 1.5 (1.2, 2.0) * | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) *** |

| Education level of parents | ||||

| Primary or lower (<9 years) | 731 (9.7) | 6794 (90.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary (9–12 years) | 191 (9.9) | 1745 (90.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| Postsecondary (>12 years) | 98 (10.6) | 831 (89.5) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) |

| Occupation of parents | ||||

| Government institution | 46 (10.0) | 414 (90.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Business or service industry | 347 (9.6) | 3281 (90.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.3) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) |

| Farmer | 213 (11.4) | 1650 (88.6) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.6) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.0) |

| Stay-at-home mother/stay-at-home father/unemployed | 213 (9.5) | 2032 (90.5) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) | 1.2 (0.4, 1.9) |

| Other (retired/business owner, etc.) | 201 (9.2) | 1993 (90.8) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) |

| Annual household income (RMB) | ||||

| <100,000 | 572 (9.8) | 5249 (90.2) | 1 | 1 |

| 100,000–200,000 | 288 (9.3) | 2812 (90.7) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) |

| >200,000 | 160 (10.9) | 1309 (89.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) |

| Immigration status | ||||

| Resident | 884 (10.2) | 7774 (89.8) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) ** | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) ** |

| Migrant from other counties of China | 136 (7.9) | 1596 (92.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Influenza vaccin ation status | ||||

| Yearly | 291 (18.5) | 1280 (81.5) | 3.2 (2.7, 3.9) *** | 2.1 (1.7, 2.7) *** |

| Some years | 543 (9.1) | 5450 (90.9) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) *** | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) *** |

| Never | 186 (6.6) | 2640 (93.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Marital status of parents | ||||

| Married | 918 (9.7) | 8569 (90.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Other (divorced/widowed/separated, etc.) | 102 (11.3) | 801 (88.7) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) |

| Parental HPV vaccin ation status | ||||

| Yes | 382 (31.7) | 824 (68.3) | 6.2 (5.4, 7.2) *** | 6.2 (5.3, 7.2) *** |

| No | 638 (7.0) | 8546 (93.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Is cervical cancer one of the most common genital-system cancers among women worldwide? | ||||

| Yes | 931 (9.7) | 8671 (90.3) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 89 (11.3) | 699 (88.7) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) |

| Do you agree that prevention of cervical cancer does not just concern older women? | ||||

| Yes | 662 (10.4) | 5716 (89.6) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 358 (8.9) | 3654 (91.1) | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) * | 0.9 (0.7, 1.0) |

| Do you think HPV causes cervical cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 865 (9.9) | 7855 (90.1) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 155 (9.3) | 1515 (90.7) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) |

| Is HPV primarily transmitted among humans through sex? | ||||

| Yes | 774 (10.0) | 6991 (90.0) | 1 | 1 |

| No | 246 (9.4) | 2379 (90.6) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) |

| Are you aware that there are vaccines for cervical cancer? | ||||

| Yes | 758 (11.6) | 5774 (88.4) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) *** | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) *** |

| No | 340 (8.8) | 3518 (91.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Do you know the optimal age for HPV vaccination? | ||||

| Yes | 344 (20.1) | 1366 (79.9) | 3.0 (2.6, 3.4) *** | 2.9 (2.5, 3.4) *** |

| No | 676 (7.8) | 8004 (92.2) | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Ling, J.; Zhao, X.; Lv, Q.; Wang, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X. Are HPV Vaccines Well Accepted among Parents of Adolescent Girls in China? Trends, Obstacles, and Practical Implications for Further Interventions: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091073

Huang Y, Ling J, Zhao X, Lv Q, Wang L, Wu Q, Xu S, Zhang X. Are HPV Vaccines Well Accepted among Parents of Adolescent Girls in China? Trends, Obstacles, and Practical Implications for Further Interventions: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Vaccines. 2024; 12(9):1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091073

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yu, Jie Ling, Xiang Zhao, Qiaohong Lv, Lei Wang, Qingqing Wu, Shuiyang Xu, and Xuehai Zhang. 2024. "Are HPV Vaccines Well Accepted among Parents of Adolescent Girls in China? Trends, Obstacles, and Practical Implications for Further Interventions: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study" Vaccines 12, no. 9: 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091073

APA StyleHuang, Y., Ling, J., Zhao, X., Lv, Q., Wang, L., Wu, Q., Xu, S., & Zhang, X. (2024). Are HPV Vaccines Well Accepted among Parents of Adolescent Girls in China? Trends, Obstacles, and Practical Implications for Further Interventions: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Vaccines, 12(9), 1073. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12091073