Is a COVID-19 Vaccine Likely to Make Things Worse?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

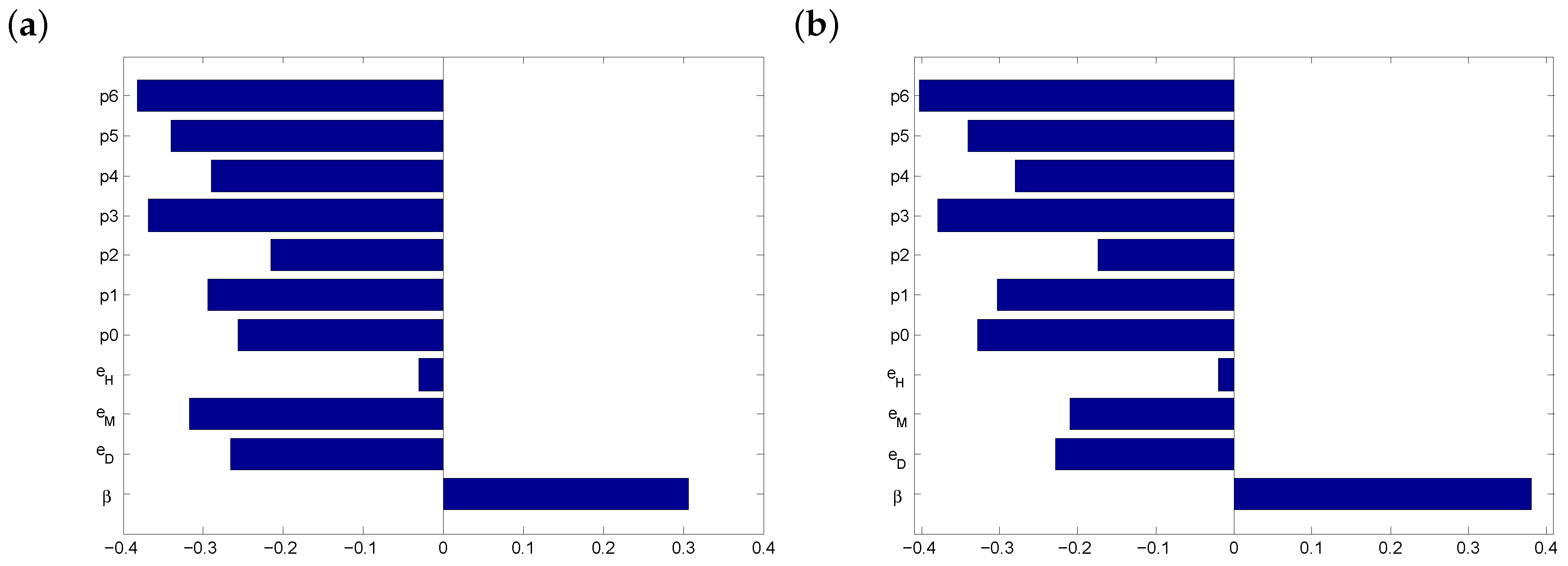

3.1. Parameter Estimates

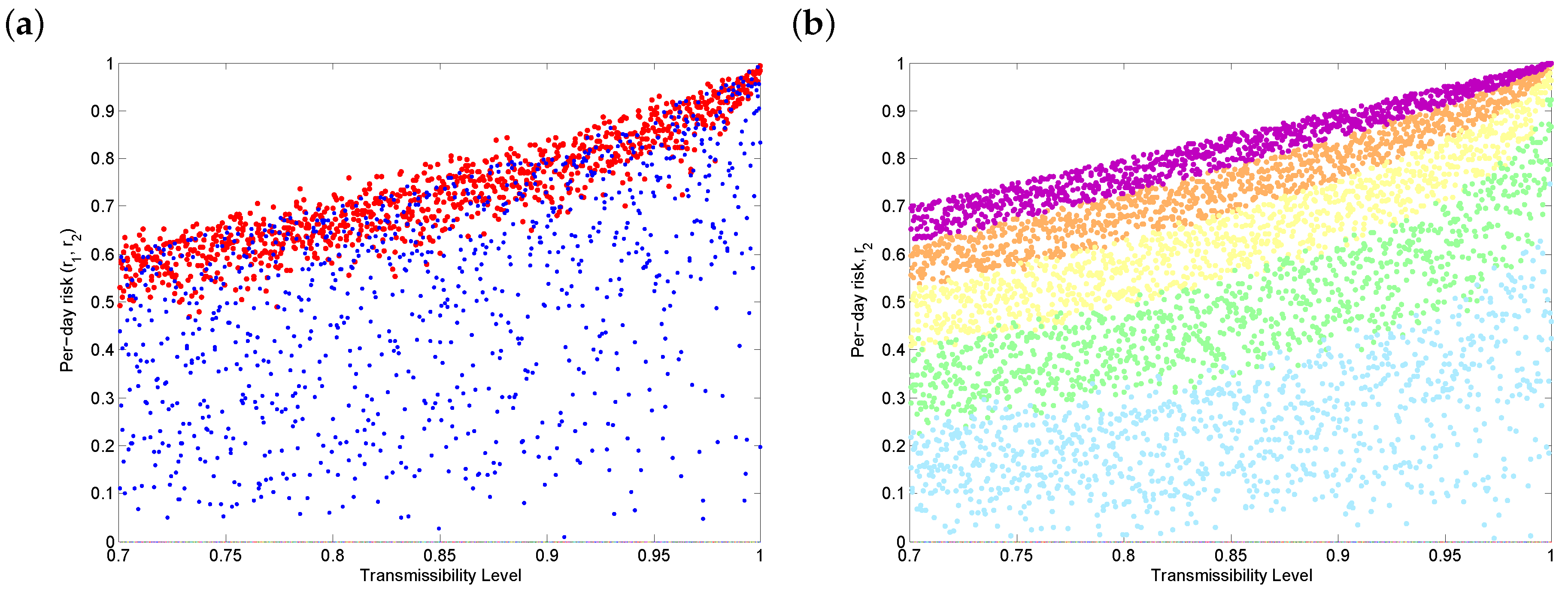

3.2. Before Vaccination

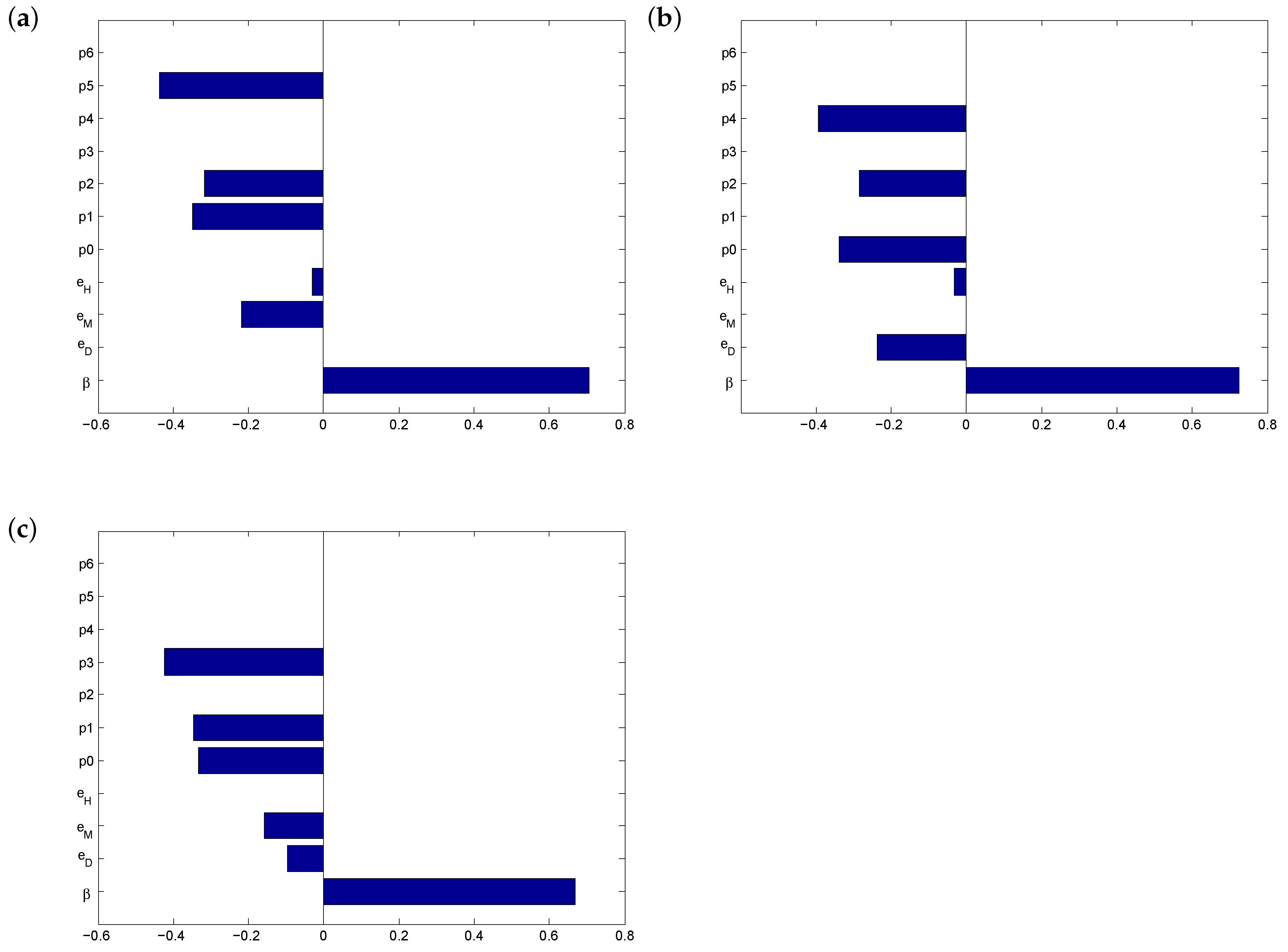

3.3. After Vaccination

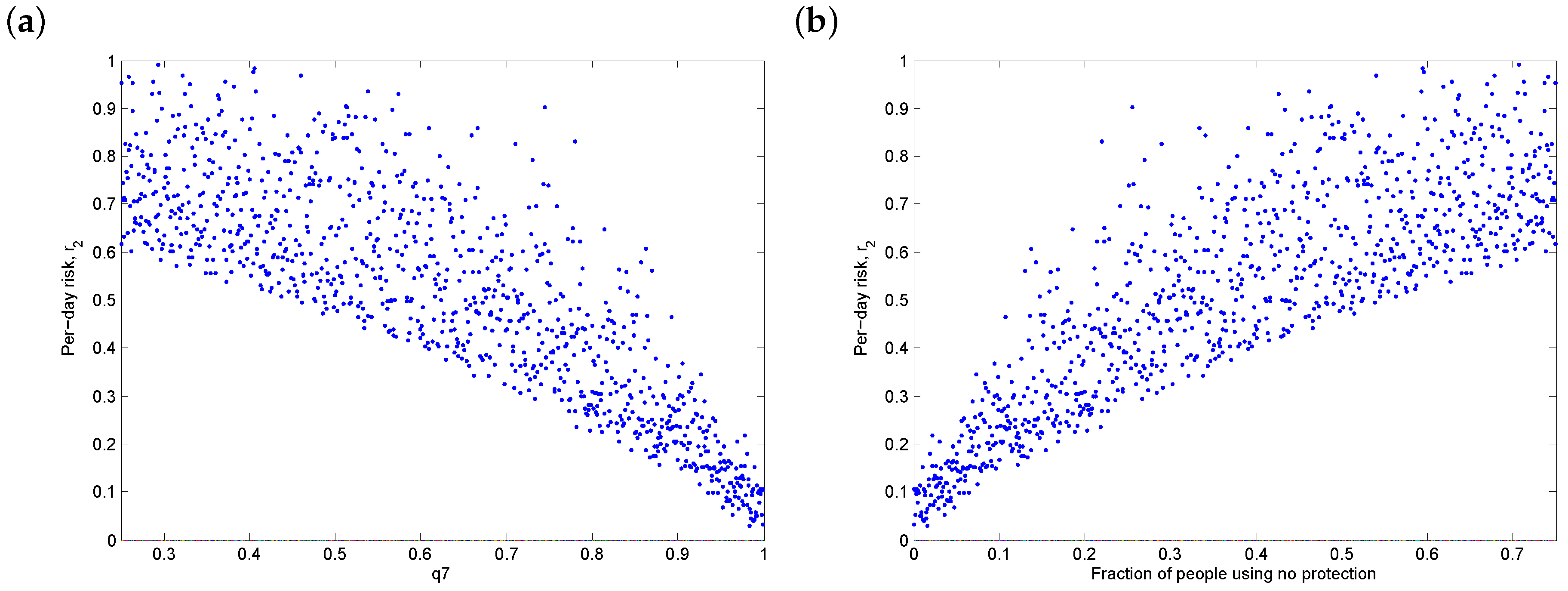

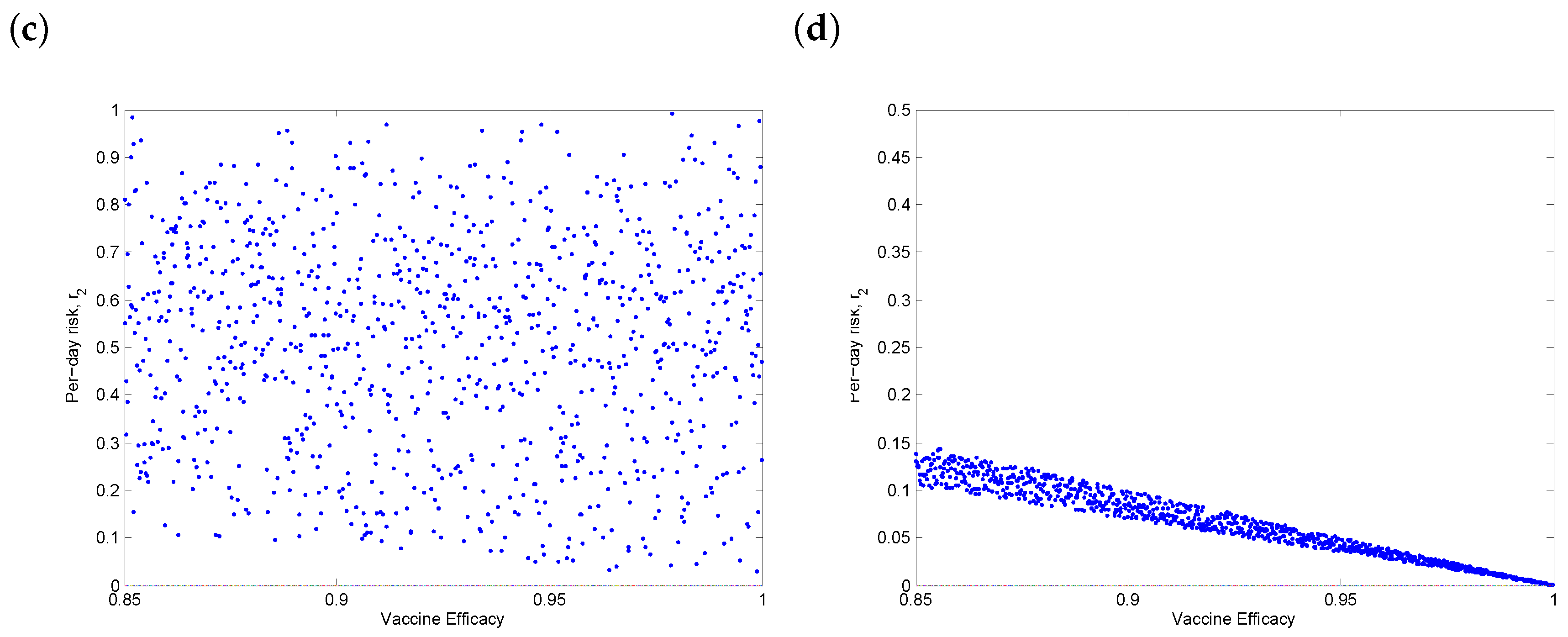

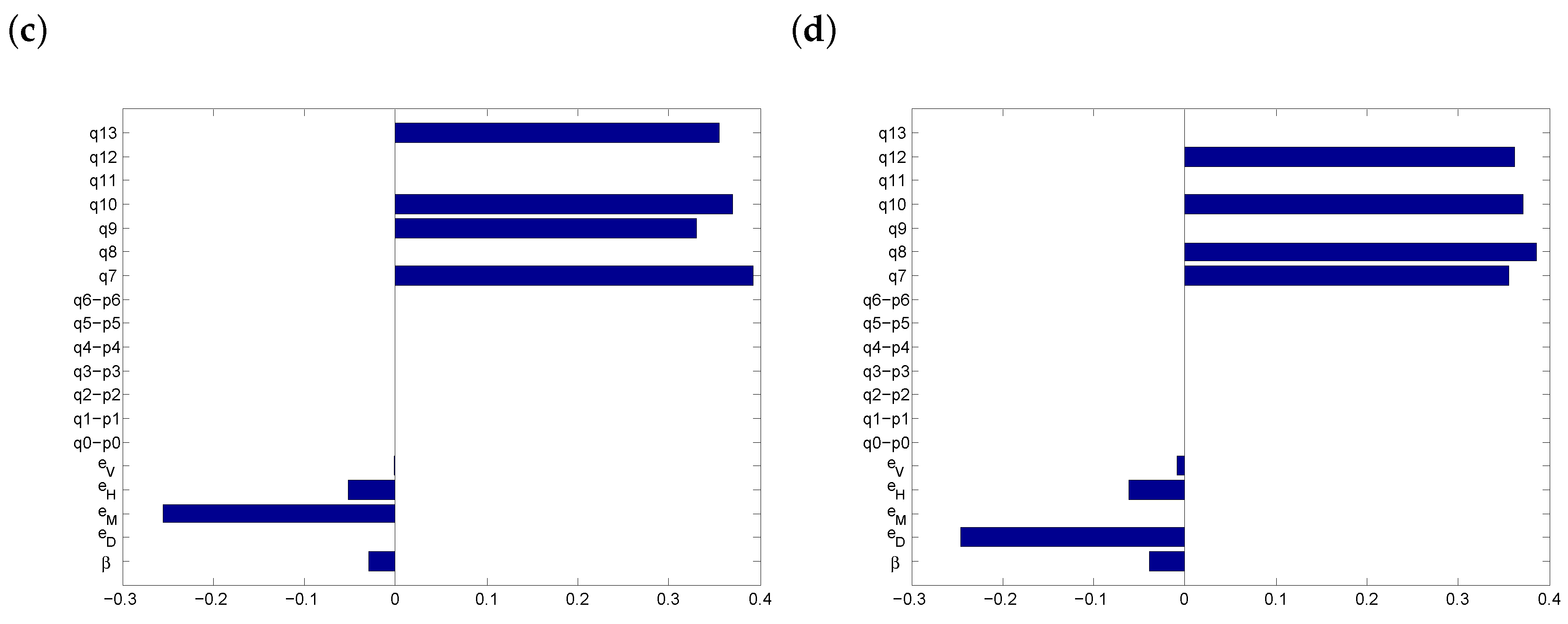

3.4. Threshold Behaviour

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothan, H.; Byrareddy, S. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Gayle, A.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Rocklöv, J. The Reproductive Number of COVID-19 Is Higher Compared to SARS Coronavirus. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, W.; Ni, Z.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.H.; Ou, C.Q.; He, J.X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.L.; Hui, D.S.; et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xiang, Z.; Guo, L.; Xu, T.; Jiang, Y.Z.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.J.; Li, X.W.; et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: A descriptive study. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tang, J.; Wei, F. Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, W.; Dela Cruz, C.; Cao, B.; Pasnick, S.; Jamil, S. Novel Wuhan (2019-nCoV) coronavirus. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xuhua, G.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.; Lau, E.H.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. J. Surg. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, A.; Lane, H.; Redfield, R. COVID-19—navigating the uncharted. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1268–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfizer and BioNTech Conclude Phase 3 Study of COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate, Meeting All Primary Efficacy Endpoints. 2020. Available online: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-conclude-phase-3-study-covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Moderna’s COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate Meets its Primary Efficacy Endpoint in the First, Interim Analysis of the Phase 3 COVE Study. 2020. Available online: https://investors.modernatx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/modernas-covid-19-vaccine-candidate-meets-its-primary-efficacy (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Le, T.; Andreadakis, Z.; Kumar, A.; Roman, R.; Tollefsen, S.; Saville, M.; Mayhew, S. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boodoosingh, R.; Olayemi, L.; Sam, F. COVID-19 vaccines: Getting Anti-vaxxers involved in the discussion. World Dev. 2020, 136, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, D.; Heyward, W.; Popovic, V.; Orozco-Cronin, P.; Orelind, K.; Gee, C.; Hirsch, A.; Ippolito, T.; Luck, A.; Longhi, M.; et al. Candidate HIV/AIDS vaccines: Lessons learned from the world’s first phase III efficacy trials. AIDS 2003, 17, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Blower, S. Could disease-modifying HIV vaccines cause population-level perversity? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costris-Vas, C.; Schwartz, E.; Smith?, R. Predicting COVID-19 using past pandemics as a guide: How reliable were mathematical models then, and how reliable will they be now? Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020, 17, 7502–7518. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, L.; Smith?, R. Modelling Global Outbreaks and Proliferation of COVID-19. SIAM News 2020, 53, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Diao, M.; Yu, W.; Pei, L.; Lin, Z.; Chen, D. Estimation of the reproductive number of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and the probable outbreak size on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: A data-driven analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucharski, A.; Russell, T.; Diamond, C.; Liu, Y.; Edmunds, J.; Funk, S.; Eggo, R.; Sun, F.; Jit, M.; Munday, J.; et al. Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkeson, A. What will be the economic impact of COVID-19 in the US? Rough estimates of disease scenarios. Natl. Bur. Econ. Res. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell, J.; Abbott, S.; Gimma, A.; Bosse, N.; Jarvis, C.; Russell, T.; Munday, J.; Kucharski, A.; Edmunds, W.; Sun, F.; et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e488–e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, K.; Liu, Y.; Russell, T.; Kucharski, A.; Eggo, R.; Davies, N.; Flasche, S.; Clifford, S.; Pearson, C.; Munday, J.; et al. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e261–e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntner, P.; Colantonio, L.; Cushman, M.; Goff, D.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.; Kissela, B.; Levitan, E.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; Safford, M. Validation of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Pooled Cohort risk equations. JAMA 2014, 311, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangri, N.; Grams, M.; Levey, A.; Coresh, J.; Appel, L.; Astor, B.; Chodick, G.; Collins, A.; Djurdjev, O.; Elley, C.; et al. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 315, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, R.; Coleman, R.; Price, H.; Holman, R.; Khaw, K.; Wareham, N.; Griffin, S. Performance of the UK prospective diabetes study risk engine and the Framingham risk equations in estimating cardiovascular disease in the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petoumenos, K.; Reiss, P.; Ryom, L.; Rickenbach, M.; Sabin, C.; El-Sadr, W.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; De Wit, S.; Kirk, O.; Dabis, F. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with age in HIV-positive men: A comparison of the D: A: D CVD risk equation and general population CVD risk equations. HIV Med. 2014, 15, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.; Bodine, E.; Wilson, D.; Blower, S. Evaluating the potential impact of vaginal microbicides in reducing the risk of HIV acquisition in female sex workers. AIDS 2005, 19, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo, S.M.; Smith?, R. Modelling the daily risk of Ebola in the presence and absence of a potential vaccine. Infect. Dis. Model. 2020, 5, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobel, H.; Jerico, C.; Montero, M.; Sorli, M.; Velat, M.; Guelar, A.; Saballs, P.; Pedro-Botet, J. Global cardiovascular risk in patients with HIV infection: Concordance and differences in estimates according to three risk equations (Framingham, SCORE, and PROCAM). AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, H.; Furusawa, Y.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Imai, M.; Kabata, H.; Nishimura, H.; Kawaoka, Y. Effectiveness of Face Masks in Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. MSphere 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kelly, E.; Pirog, S.; Ward, J.; Clarkson, P.J. Ability of fabric face mask materials to filter ultrafine particles at coughing velocity. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Cappa, C.D.; Barreda, S.; Wexler, A.S.; Bouvier, N.M.; Ristenpart, W.D. Efficacy of masks and face coverings in controlling outward aerosol particle emission from expiratory activities. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rundle, C.; Presley, C.; Militello, M.; Barber, C.; Powell, D.; Jacob, S.; Atwater, A.; Watsky, K.; Yu, J.; Dunnick, C. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: Recommendations from the American contact dermatitis society. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blower, S.; Dowlatabadi, H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission: An HIV model, as an example. Int. Stat. Rev. 1994, 2, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Definition | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Transmissibility | 0.7–1 | |

| Physical distancing | 0.21–0.78 | |

| Face coverings | 0.2–0.9 | |

| Handwashing | 0.24–0.31 | |

| Vaccine efficacy | 0.85–1 | |

| Fraction of people practicing only physical distancing | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people only wearing face coverings | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people only practicing regular handwashing | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people practicing physical distancing and | ||

| wearing face coverings | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people practicing physical distancing and | ||

| regular handwashing | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people wearing face coverings with regular handwashing | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people practicing physical distancing with regular | ||

| handwashing and wearing face coverings | 0–0.125 | |

| Fraction of people only practicing physical distancing post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people only wearing face coverings post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people only practicing regular handwashing post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people practicing physical distancing and | ||

| wearing face coverings post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people practicing physical distancing and | ||

| regular handwashing post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people wearing face coverings with regular | ||

| handwashing post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people practicing physical distancing with regular | ||

| handwashing and wearing face coverings post-vaccination | 0 | |

| Fraction of people using only the vaccine | 0–1 | |

| Fraction of people using the vaccine and practicing physical distancing | 0–0.142 | |

| Fraction of people using the vaccine and wearing face coverings | 0–0.142 | |

| Fraction of people using the vaccine with handwashing | 0–0.142 | |

| Fraction of people using the vaccine, practicing physical distancing | ||

| and wearing face coverings | 0–0.142 | |

| Fraction of people using the vaccine, practicing physical distancing | ||

| with handwashing | 0–0.142 | |

| Fraction of people using the vaccine, wearing face coverings | ||

| with handwashing | 0–0.142 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abo, S.M.C.; Smith?, S.R. Is a COVID-19 Vaccine Likely to Make Things Worse? Vaccines 2020, 8, 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040761

Abo SMC, Smith? SR. Is a COVID-19 Vaccine Likely to Make Things Worse? Vaccines. 2020; 8(4):761. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040761

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbo, Stéphanie M. C., and Stacey R. Smith?. 2020. "Is a COVID-19 Vaccine Likely to Make Things Worse?" Vaccines 8, no. 4: 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040761

APA StyleAbo, S. M. C., & Smith?, S. R. (2020). Is a COVID-19 Vaccine Likely to Make Things Worse? Vaccines, 8(4), 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8040761