Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Portuguese-Speaking Countries: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Location

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

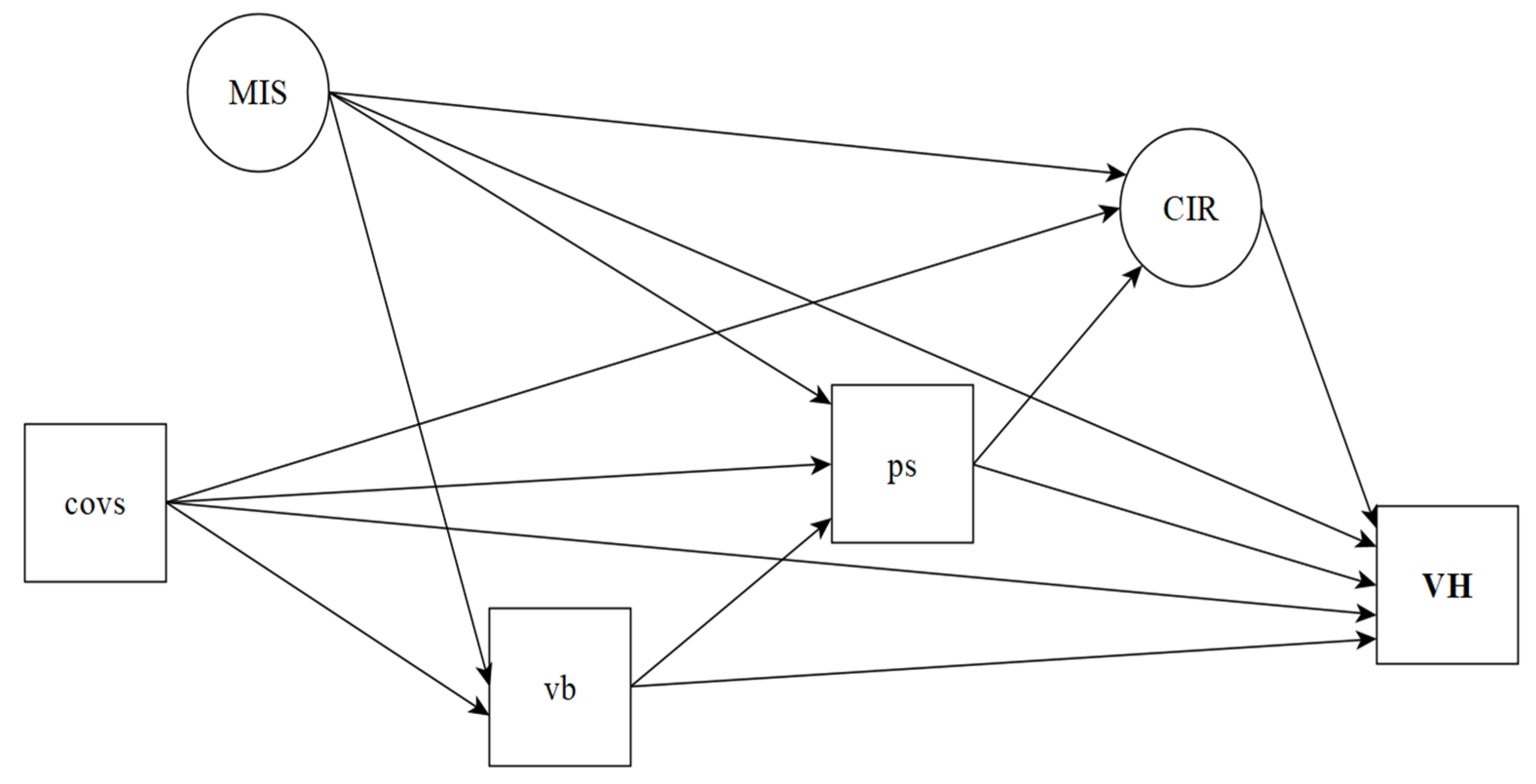

2.4. Conceptual Structure and Study Hypotheses

2.5. Data Analysis Procedures

2.6. Ethical and Legal Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

3.2. Prevalence of Vaccine Hesitancy

3.3. Latent Variable Measurement Models

3.4. Stratified Measurement Models

3.5. Structural Equation Model of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Hesitancy

3.6. Stratified Structural Equation Models of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Hesitancy

3.7. Standardized Total and Indirect Effects of the Structural Equation Model of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Hesitancy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harrison, E.A.; Wu, J.W. Vaccine confidence in the time of COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fontanet, A.; Cauchemez, S. COVID-19 herd immunity: Where are we? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2020, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid systematic review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzymski, P.; Borkowski, L.; Drąg, M.; Flisiak, R.; Jemielity, J.; Krajewski, J.; Mastalerz-Migas, A.; Matyja, A.; Pyrć, K.; Simon, K.; et al. The strategies to support the COVID-19 vaccination with evidence-based communication and tackling misinformation. Vaccines 2021, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrunaga-Pastor, D.; Bendezu-Quispe, G.; Herrera-Añazco, P.; Uyen-Cateriano, A.; Toro-Huamanchumo, C.J.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Hernandez, A.V.; Benites-Zapata, V.A. Cross-sectional analysis of COVID-19 vaccine intention, perceptions and hesitancy across Latin America and the Caribbean. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 41, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, P.; Barham, E.; Daly, S.Z.; Gerez, J.E.; Marshall, J.; Pocasangre, O. The Shot, the Message, and the Messenger: COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Latin America. Available online: https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jmarshall/files/vaccineshesitancypaper2.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Glymour, M.M.; Greenland, S. Causal diagrams. In Modern Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Rothman, K.J., Greenland, S., Lash, T.L., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008; Chapter 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hernan, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Causal inference: What if. In A Chapman & Hall Book; CRC Press: Boca Raton FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Werneck, G.L. Diagramas causais: A epidemiologia brasileira de volta para o futuro. Cadernos Saúde Pública 2016, 32, e00120416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cortes, T.R.; Faerstein, E.; Struchiner, C.J. Utilização de diagramas causais em epidemiologia: Um exemplo de aplicação em situação de confusão. Cadernos Saúde Pública 2016, 32, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; van der Linden, S. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barua, Z.; Barua, S.; Aktar, S.; Kabir, N.; Li, M. Effects of misinformation on COVID-19 individual responses and recommendations for resilience of disastrous consequences of misinformation. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 8, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy Making. Council Europe Report. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/information-disorder-toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework-for-researc/168076277c (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Shahi, G.K.; Dirkson, A.; Majchrzak, T.A. An exploratory study of COVID-19 misinformation on Twitter. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2021, 22, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, M.; Luchsinger, L.; Bearth, A. The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID-19 cases. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, G.L.; Gentile, A.; Bosnar, K.; Milovanović, I.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P.; Pišot, S. A cross-country examination on the fear of COVID-19 and the sense of loneliness during the first wave of COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlapani, E.; Holeva, V.; Voitsidis, P.; Blekas, A.; Gliatas, I.; Porfyri, G.-N.; Golemis, A.; Papadopoulou, K.; Dimitriadou, A.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.F.; et al. Psychological and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnam, H.B.; Akondi, B.R. Post-COVID Stress disorder: An emerging upshot of the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Health Care 2020, 13, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, Z. Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19? Prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, G.K.; Holding, A.; Perez, S.; Amsel, R.; Rosberger, Z. Validation of the vaccine conspiracy beliefs scale. Papillomavirus Res. 2016, 2, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: A study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, P.; Nera, K.; Delouvée, S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: A conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 565128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević-Djordjević, J.; Mari, S.; Vdović, M.; Milošević, A. Links between conspiracy beliefs, vaccine knowledge, and trust: Anti-vaccine behaviour of Serbian adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 277, 113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Douglas, K.M. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hviid, A.; Hansen, J.V.; Frisch, M.; Melbye, M. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccination and autism: A nationwide cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomljenovic, H.; Bubic, A.; Erceg, N. It just doesn’t feel right—The relevance of emotions and intuition for parental vaccine conspiracy beliefs and vaccination uptake. Psychol. Health 2020, 35, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrozo-Pupo, J.C.; Pedrozo-Cortés, M.J.; Campo-Arias, A. Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia: An online survey. Cadernos Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00090520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software e Aplicações, 2nd ed.; ReportNumber: Lisboa, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.; Muthén, B.; Asparouhov, T.; Lüdtke, O.; Robitzsch, A.; Morin, A.; Trautwein, U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluations of University Teaching. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2009, 16, 439–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Análise Multivariada de Dados, 6th ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Reichenheim, M.E.; Hökerberg, Y.H.M.; de Moraes, C.L. Assessing construct structural validity of epidemiological measurement tools: A seven-step roadmap. Cadernos Saúde Pública 2014, 30, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Methodology in the social sciences. In Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Razai, M.S.; Osama, T.; McKechnie, D.G.J.; Majeed, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority groups. BMJ 2021, 372, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, R.; Yoshioka, T.; Ohfuji, S.; Matsuo, T.; Tabuchi, T. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its associated factors in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, E.; Reeve, K.S.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Moore, J.; Blake, M.; Green, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Benzeval, M.J. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 94, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Fielding, K.S. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germani, F.; Biller-Andorno, N. The anti-vaccination infodemic on social media: A behavioral analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Mesquita, C.T.; Oliveira, A.; Seixas, F.L.; Paes, A. Infodemia, Fake news and medicine: Science and the quest for truth. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2020, 33, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, M.A. Misinformation and public opinion of science and health: Approaches, findings, and future directions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 1912437117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhardi, C.P.; Freire, N.P.; Minayo, M.C.D.S.; Fagundes, M.C.M. Fact or fake? An analysis of disinformation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2020, 25, 4201–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurković, M.; Košec, A.; Bedeković, M.R.; Bedeković, V. Epistemic responsibilities in the COVID-19 pandemic: Is a digital infosphere a friend or a foe? J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 115, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, S.J.; Steyrl, D.; Stefańczyk, M.; Pieniak, M.; Molina, J.M.; Pešout, O.; Binter, J.; Smela, P.; Scharnowski, F.; Nicholson, A.A. Predicting fear and perceived health during the COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning: A cross-national longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; McCaul, K.D.; Weinstein, N.D. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 2007, 26, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, K.; Cvejic, E.; Nickel, B.; Copp, T.; Bonner, C.; Leask, J.; Ayre, J.; Batcup, C.; Cornell, S.; Dakin, T.; et al. COVID-19 Misinformation Trends in Australia: Prospective Longitudinal National Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, N.P. What Is Driving COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Sub-Saharan Africa? Africa Can End Poverty. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/what-driving-COVID-19-vaccine-hesitancy-sub-saharan-africa (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Otu, A.; Osifo-Dawodu, E.; Atuhebwe, P.; Agogo, E.; Ebenso, B. Beyond vaccine hesitancy: Time for Africa to expand vaccine manufacturing capacity amidst growing COVID-19 vaccine nationalism. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e347–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Conversation. Vaccine Hesitancy Has Risen in Ghana: A Closer Look at Who’s Worried. Available online: https://theconversation.com/vaccine-hesitancy-has-risen-in-ghana-a-closer-look-at-whos-worried-164733 (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Health Europe. Is Vaccine Hesitancy in Africa Linked to Institutional Mistrust? Available online: https://www.healtheuropa.eu/is-vaccine-hesitancy-in-africa-linked-to-institutional-mistrust/108929/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Chang, K.-C.; Strong, C.; Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.-Y. Factors related to preventive COVID-19 infection behaviors among people with mental illness. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yao, X.; Wen, N. What motivates Chinese consumers to avoid information about the COVID-19 pandemic? The perspective of the stimulus-organism-response model. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosostolato, B. Alexitimia e masculinidades: Do silêncio aos processos de desconstrução. Rev. Bras. Sex Hum. 2019, 30, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Griffiths, M.D. The fear of COVID-19 and its role in preventive behaviors. J. Concurr. Disord. 2020, 2, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rad, R.E.; Mohseni, S.; Takhti, H.K.; Azad, M.H.; Shahabi, N.; Aghamolaei, T.; Norozian, F. Application of the protection motivation theory for predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Hormozgan, Iran: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variables | Indicator Variables (Codes) | λ | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIR | |||

| Avoiding bars, restaurants, and events (R1) | 0.654 | <0.001 | |

| Using disinfectants for cleaning the environment (R2) | 0.511 | <0.001 | |

| Hand hygiene with soap and water, and alcoholic solution (R3) | 0.777 | <0.001 | |

| Postponing national or international travels (R4) | 0.654 | <0.001 | |

| Working remotely (R5) | 0.609 | <0.001 | |

| Supplying goods (R6) | 0.614 | <0.001 | |

| Social isolation to prevent crowding (R7) | 0.645 | <0.001 | |

| Using a face shield (R8) | 0.609 | <0.001 | |

| CB | |||

| The virus was created in the laboratory by Chinese scientists (C1) | 0.770 | <0.001 | |

| There was genetic manipulation of the virus to cause AIDS (C2) | 0.602 | <0.001 | |

| Social isolation can reduce immunity and facilitate virus infection (C3) | 0.458 | <0.001 | |

| Positive asymptomatic people do not transmit the virus to other people (C4) | 0.871 | <0.001 | |

| The virus was spread by the pharmaceutical industry for population control (C5) | 0.722 | <0.001 | |

| GB | |||

| Avocado, hibiscus, perfume aerosols, and whiskey tea have a preventive potential (G1) | 0.851 | <0.001 | |

| Alcoholic solution is more efficient than washing hands with soap and water as a preventive measure (G2) | 0.496 | <0.001 | |

| Daily use of alcohol gel can be toxic and extremely harmful to health (G3) | 0.661 | <0.001 | |

| The virus can be eliminated from the body by drinking water and gargling with warm water, saline, or acidic solutions, thus preventing the infection (G4) | 0.719 | <0.001 | |

| Vinegar is better than alcohol to avoid contamination by COVID-19 (G5) | 0.637 | <0.001 | |

| Autohemotherapy is very effective against the new coronavirus (G6) | 0.896 | <0.001 | |

| Eating garlic prevents contagion by the new coronavirus (G7) | 0.881 | <0.001 | |

| The virus does not survive temperatures above 26 degrees (G8) | 0.856 | <0.001 | |

| Drinking clean water every 15 min expels the new coronavirus, as it prevents it from going to the lungs (G9) | 0.855 | <0.001 | |

| r | CB1↔GB | ||

| 0.949 | <0.001 | ||

| CB a | |||

| GB a | 0.559 | <0.001 | |

| 0.796 | <0.001 | ||

| r b | C11↔C2 | ||

| C11↔C5 | 0.477 | <0.001 | |

| C31↔C4 | 0.385 | <0.001 | |

| G41↔G9 | 0.210 | <0.001 | |

| G71↔G9 | 0.316 | <0.001 | |

| CB1↔GB | 0.217 | <0.001 |

| Adjustment Pathways/Indices | Gender | Age (Years) | Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 18 to 29 | 30 to 49 | 50 or More | Elementary and High School | University | |

| Ancestors of VH | |||||||

| COVS→VH | −0.007 | 0.027 | 0.098 | 0.004 | /0.040 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| MIS→VH | 0.317 ** | 0.269 ** | 0.285 * | 0.673 ** | −0.008 | 0.233 ** | 0.245 ** |

| CIR→VH | −0.152 * | −0.122 * | −0.291 * | −0.110 | −0.410 ** | −0.106 * | −0.098 * |

| PS→VH | 0.297 ** | 0.344 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.111 | 0.151 * | 0.320 ** | 0.318 ** |

| GB→VH | 0.795 ** | 0.953 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.906 ** | 0.911 ** | 0.905 ** |

| Descendants of COVS | |||||||

| COVS→PS | −0.265 ** | −0.062 | −0.106 | −0.195 ** | −0.077 | −0.128 * | −0.128 * |

| COVS→GB | −0.085 | 0.068 * | 0.037 | 0.008 | 0.051 | 0.037 | 0.037 |

| COVS→CIR | −0.180 ** | 0.042 | 0.133 * | −0.188 ** | 0.066 | −0.081 * | −0.110 ** |

| Descendants of MIS | |||||||

| MIS→PS | −0.059 | −0.132 | −0.148 | −0.304 * | −0.043 | −0.062 | −0.067 |

| MIS→GB | 0.372 ** | 0.365 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.617 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.333 ** |

| MIS→CIR | 0.002 | −0.007 | −0.131 | 0.199 * | −0.119 | −0.043 | −0.022 |

| PS descendants | |||||||

| PS→CIR | 0.138 * | 0.088 | 0.359 ** | 0.039 | 0.066 | 0.054 | 0.049 |

| Descendants of VB | |||||||

| GB→PS | −0.163 * | −0.461 ** | −0.155 * | −0.097 | −0.200 | −0.324 ** | −0.320 ** |

| r a | |||||||

| CB1↔GB | 0.820 ** | 0.828 ** | 0.845 ** | 0.942 ** | 0.739 ** | 0.815 ** | 0.822 ** |

| R21↔R3 | 0.376 ** | 0.361 | 0.187 | 0.594 * | 0.517 | − | 0.587 ** |

| C11↔C2 | 0.376 ** | 0.430 ** | 0.538 ** | 0.471 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.405 ** | 0.408 ** |

| C11↔C5 | 0.338 ** | 0.361 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.498 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.345 ** |

| C31↔C4 | 0.178 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.226 ** | 0.170 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.168 ** | 0.167 ** |

| G31↔G7 | −0.148 ** | −0.187 ** | −0.129 * | −0.206 ** | −0.211 * | −0.202 ** | −0.179 ** |

| G41↔G9 | 0.484 ** | 0.270 ** | 0.427 ** | 0.171 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.280 ** | 0.309 ** |

| G41↔G8 | 0.134 * | 0.164 ** | 0.090 | 0.203 ** | −0.011 | 0.160 ** | 0.158 ** |

| G71↔G9 | 0.490 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.332 * | 0.258 ** | 0.313 ** | 0.368 ** | 0.335 ** |

| G81↔G9 | 0.258 ** | 0.180 | 0.262 ** | 0.109 * | 0.176 * | 0.188 ** | 0.187 ** |

| Fit indices | |||||||

| RMSEA | |||||||

| Index | 0.055 | 0.036 | 0.041 | 0.039 | 0.060 | 0.038 | 0.037 |

| 90%CI | 0.051–0.059 | 0.037–0.046 | 0.026–0.029 | 0.036–0.042 | 0.054–0.066 | 0.036–0.041 | 0.034–0.039 |

| CFI | 0.975 | 0.987 | 0.995 | 0.988 | 0.995 | 0.989 | 0.988 |

| TLI | 0.971 | 0.985 | 0.995 | 0.986 | 0.995 | 0.987 | 0.987 |

| Pathways | General | Gender | Age Group (Years) | Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | 18 to 29 | 30 to 49 | 50 or More | Elementary and High School | University | ||

| Total effects | ||||||||

| COVS→VH | −0.009 | −0.117* | 0.056 | 0.028 | 0.008 | −0.031 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| MIS→VH | 0.523 ** | 0.579 ** | 0.517 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.911 * | 0.372 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.495 ** |

| CIR→VH | −0.122 * | −0.152 * | −0.122 * | −0.291 * | −0.110 | −0.410 ** | −0.106 * | −0.098 * |

| PS→VH | 0.305 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.107 | 0.124 | 0.314 ** | 0.314 ** |

| GB→VH | 0.795 ** | 0.750 ** | 0.799 ** | 0.514 ** | 0.474 ** | 0.881 ** | 0.809 ** | 0.804 * |

| Specific indirect effects | ||||||||

| COVS | ||||||||

| COVS→PS→VH | −0.050 ** | −0.079 ** | −0.021 | −0.061 | −0.022 | −0.012 | −0.041 * | −0.041 * |

| COVS→GB→VH | 0.008 | −0.067 | 0.065 * | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.046 | 0.034 | 0.034 |

| COVS→CIR→VH | 0.010 * | 0.027 * | −0.005 | −0.039 | 0.021 | −0.027 | 0.009 * | 0.011 * |

| COVS→GB→PS→VH | −0.001 | 0.004 | −0.011 * | −0.003 | 0.000 | −0.002 | −0.004 | −0.004 |

| COVS→PS→CIR→VH | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| COVS→GB→PS→CIR→VH | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| MIS | ||||||||

| MIS→PS→VH | −0.026 | −0.018 | −0.046 | −0.085 | −0.034 | −0.006 | −0.020 | −0.021 |

| MIS→GB→VH | 0.322 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.348 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.299 ** | 0.346 ** | 0.295 ** | 0.301 ** |

| MIS→CIR→VH | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.038 | −0.022 | 0.049 | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| MIS→GB→PS→VH | −0.034 ** | −0.018 * | −0.058 ** | −0.028 * | −0.007 | −0.012 | −0.034 ** | −0.034 ** |

| MIS→PS→CIR→VH | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| MIS→GB→PS→CIR→VH | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| PS | ||||||||

| PS→CIR→VH | −0.008 | −0.021 | −0.011 | −0.104 * | −0.004 | −0.027 | −0.006 | −0.005 |

| GB | ||||||||

| GB→PS→VH | −0.094 ** | −0.048 * | −0.159 ** | −0.089 * | −0.011 | −0.030 | −0.104 ** | −0.102 * |

| GB→PS→CIR→VH | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Sousa, Á.F.L.; Teixeira, J.R.B.; Lua, I.; de Oliveira Souza, F.; Ferreira, A.J.F.; Schneider, G.; de Carvalho, H.E.F.; de Oliveira, L.B.; Lima, S.V.M.A.; de Sousa, A.R.; et al. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Portuguese-Speaking Countries: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101167

de Sousa ÁFL, Teixeira JRB, Lua I, de Oliveira Souza F, Ferreira AJF, Schneider G, de Carvalho HEF, de Oliveira LB, Lima SVMA, de Sousa AR, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Portuguese-Speaking Countries: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach. Vaccines. 2021; 9(10):1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101167

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Sousa, Álvaro Francisco Lopes, Jules Ramon Brito Teixeira, Iracema Lua, Fernanda de Oliveira Souza, Andrêa Jacqueline Fortes Ferreira, Guilherme Schneider, Herica Emilia Félix de Carvalho, Layze Braz de Oliveira, Shirley Verônica Melo Almeida Lima, Anderson Reis de Sousa, and et al. 2021. "Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Portuguese-Speaking Countries: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach" Vaccines 9, no. 10: 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101167

APA Stylede Sousa, Á. F. L., Teixeira, J. R. B., Lua, I., de Oliveira Souza, F., Ferreira, A. J. F., Schneider, G., de Carvalho, H. E. F., de Oliveira, L. B., Lima, S. V. M. A., de Sousa, A. R., de Araújo, T. M. E., Camargo, E. L. S., Oriá, M. O. B., Craveiro, I., de Araújo, T. M., Mendes, I. A. C., Ventura, C. A. A., Sousa, I., de Oliveira, R. M., ... Fronteira, I. (2021). Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Portuguese-Speaking Countries: A Structural Equations Modeling Approach. Vaccines, 9(10), 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101167