Public Perceptions and Acceptance of COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in China: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Sample

2.2. Conceptual Framework

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. COVID-19 Booster Acceptance

2.3.2. History and Priority Groups for COVID-19 Vaccination

2.3.3. Perceptions of COVID-19 Infection and Booster Vaccination

2.3.4. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

3.2. HBM Factors and Booster Vaccination Acceptance

3.3. Adjusted Analysis of Booster Acceptance

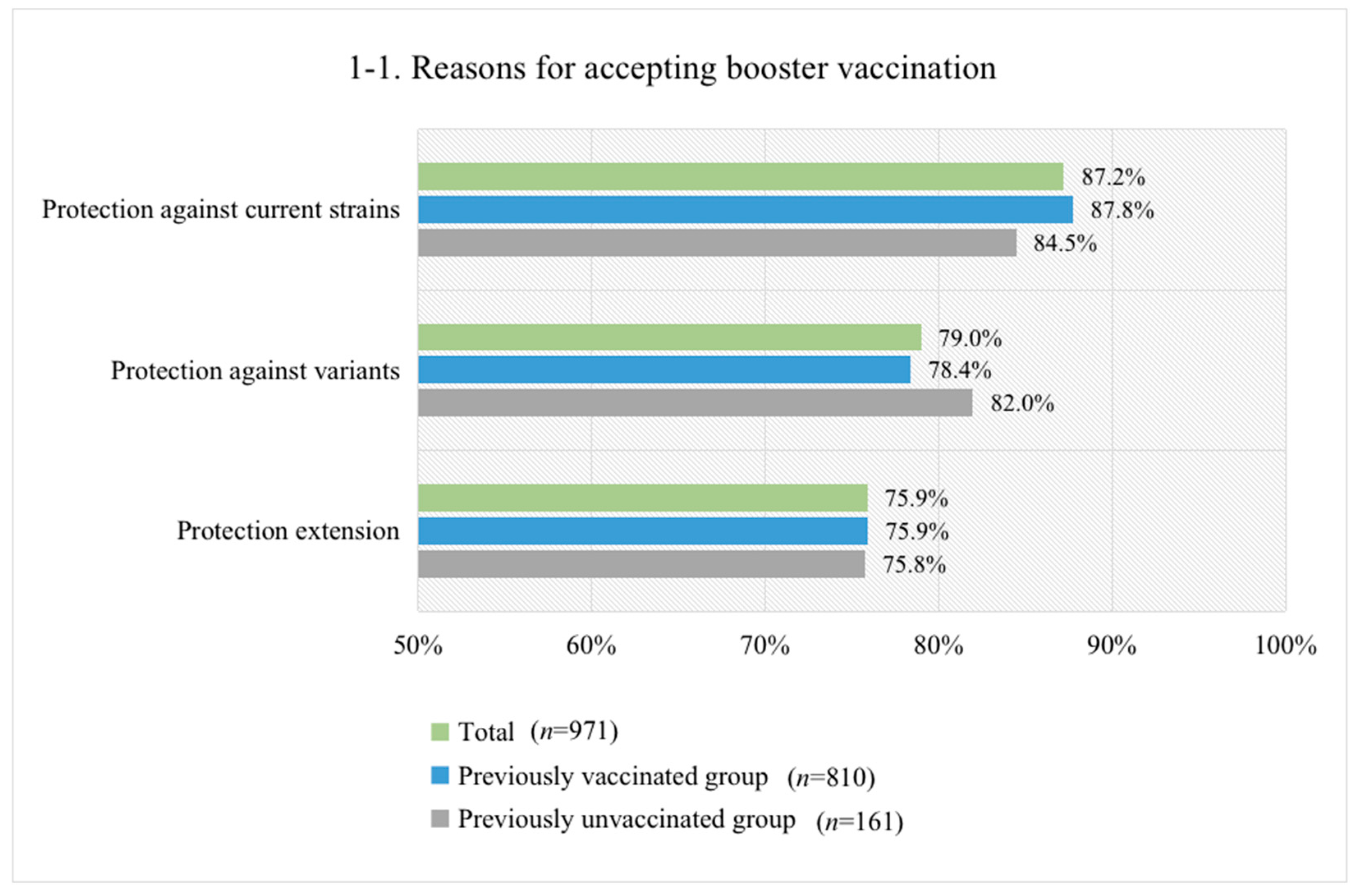

3.4. Reasons for Accepting or Not Accepting Booster Vaccination

3.5. Willingness to Pay (WTP) for an Annual Booster Vaccination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measures | Questions | Question Design and Coding |

|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 booster acceptance | If a COVID-19 booster is recommended as a supplement to the current vaccination schedule, would you accept it? | Binary (“yes [1]” or “no [0]”). |

| Multiple choices for question 1, and single choice for question 2. | |

| Willingness to pay | What is the maximum amount that you are willing to pay for an annual COVID-19 booster vaccination? | Open-ended question with values. |

| History of COVID-19 vaccination | Have you received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine so far? | Binary (“yes [1]” or “no [0]”). |

| Perceptions of COVID-19 infection and booster vaccination | Self-reported HBM items assessed on a five-point Likert scale, please see Table A2 for detail. | Five-point answers were converted to binary variables, e.g., agree [1] (i.e., “strongly agree” or “agree”) and neutral/disagree [0] (i.e., “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree” or “strongly disagree”). |

| Sociodemographics | Which age group are you currently in? | Four age groups (18–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–59 years old). |

| What is your gender? | Binary (“female [1]” or “male [0]”). | |

| What is your maternal status? | Three groups were converted to binary variables: married [1] (“married”) and never married/divorced/widowed [0] (“never married” or “divorced or widowed”). | |

| What is your education level? | Four groups were converted to binary variables: senior high school/technical school or below [0] (“middle school or below” or “senior high school/technical school”) and college/associate/bachelor’s degree or above [1] (“college/associate/bachelor’s degree” or “master’s degree or above”). | |

| What is your employment status? | Four groups were converted to binary variables: employed [1] and retired/out of work/still a student [0] (“retired”, “out of work”, or “still a student”). | |

| How much is your household annual income? | Three income groups (≤100,000, 100,001–200,000, and >200,000 CNY). | |

| Which area do you reside in? | Binary (“urban [1]” or “rural [0]”). | |

| Which province do you reside in? | Respondents were further categorized into living in western, central, and eastern regions based on the province they reside in. | |

| Rate your own overall health status. | Five-point Likert scale (“very good” to “very poor”). The answers were converted to binary variables: good [1] (“very good” or “good”) and fair/poor [0] (“fair”, “poor”, or “very poor”). | |

| Do you have any chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, etc.? | Binary (“yes [1]” or “no [0]”). | |

| Do you belong to any of the following priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination? (Health professionals, community workers, workers in the cold-chain logistics sector, customs inspectors, etc.). | Binary (“yes [1]” or “no [0]”). |

| Dimensions | Questions | Question Design |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | 1. What do you think of the risk of COVID-19 infection? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) |

| 2. Do you agree that variants have higher risk of infection than the existing strains? | Five-point Likert scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) | |

| Perceived severity | 1. What do you think of the severity of COVID-19 infection? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) |

| 2. Do you agree that variants can cause more severe illness than the existing strains? | Five-point Likert scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) | |

| Perceived benefits | 1. What do you think of the efficacy of boosters against early circulating strains if they become available in the future? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) |

| 2. What do you think of the efficacy of boosters to extend protection if they become available in the future? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) | |

| 3. What do you think of the efficacy of boosters against variants if they become available in the future? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) | |

| Perceived barriers | 1. What do you think of the safety of boosters if they become available in the future? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) |

| 2. Do you worry about serious adverse reaction after vaccination? | Five-point Likert scale (“very high” to “very low”) | |

| Self-efficacy | 1. Do you agree that it is easy for you to get the COVID-19 vaccine if you wanted to? | Five-point Likert scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) |

| Cues to action | 1. Did you use to have confirmed or suspected cases in your daily close contacts? | Binary (“yes” or “no”) |

| 2. Do you know about the following foreign variants? | Multiple choices of variants |

References

- Williams, S.V.; Vusirikala, A.; Ladhani, S.N.; De Olano, E.F.R.; Iyanger, N.; Aiano, F.; Stoker, K.; Gopal Rao, G.; John, L.; Patel, B.; et al. An outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Delta (B.1.617.2) variant in a care home after partial vaccination with a single dose of the COVID-19 vaccine Vaxzevria, London, England, April 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Nair, M.S.; Liu, L.; Iketani, S.; Luo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Kwong, P.D.; et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature 2021, 593, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Bernal, J.; Andrews, N.; Gower, C.; Gallagher, E.; Simmons, R.; Thelwall, S.; Stowe, J.; Tessier, E.; Groves, N.; Dabrera, G.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Disease Control Prevention, National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guidelines of vaccination for COVID-19 vaccines in China (First edition). Chin. J. Vir. Dis. 2021, 11, 161–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Dai, J.; Yang, Z.; Yu, X.; Xu, Y.; Shi, X.; Wei, D.; Tang, Z.; Xu, G.; Xu, W.; et al. Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine does not influence the profile of prothrombotic antibody nor increase the risk of thrombosis in a prospective Chinese cohort. Sci Bull. 2021, 66, 2312–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, D.; Khan, A.R.; Soneja, M.; Mittal, A.; Naik, S.; Kodan, P.; Mandal, A.; Maher, G.T.; Kumar, R.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated virus-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBV152, in India: A test-negative, case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, S1473-3099, 00674–00675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, A.; Cadegiani, F.A.; Wambier, C.G.; Vano-Galvan, S.; Tosti, A.; Shapiro, J.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Ramos, P.M.; Sinclair, R.; Lupi, O.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia may be associated with weaker COVID-19 T-cell immune response: An insight into a potential COVID-19 vaccine booster. Med. Hypotheses 2021, 146, 110439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarascio, F. WHO Estimates COVID-19 Boosters Needed Yearly for Most Vulnerable. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/953694 (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Israel Gives COVID-19 Booster Shots to People over 60. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-08/02/c_1310101385.htm (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on 31 December 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz177/index.htm (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Real-Time Tracking of COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://news.qq.com/zt2020/page/feiyan.htm#/ (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Barrett, J.R.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; Dold, C.; Ewer, K.J.; Folegatti, P.M.; Gilbride, C.; Halkerston, R.; Hill, J.; Jenkin, D.; Stockdale, L.; et al. Phase 1/2 trial of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 with a booster dose induces multifunctional antibody responses. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyu, W. COVID-19 Boosters for Most Not Necessary Now: Researcher. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202107/31/WS61050dcfa310efa1bd665b97.html (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Lai, X.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fenghuang, Y.; Jing, R.; Li, L.; Yu, W.; Fang, H. The Changing Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination in Different Epidemic Phases in China: A Longitudinal Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szilagyi, P.G.; Thomas, K.; Shah, M.D.; Vizueta, N.; Cui, Y.; Vangala, S.; Kapteyn, A. National Trends in the US Public’s Likelihood of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine-April 1 to December 8, 2020. JAMA 2020, 325, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in the US: Longitudinal evidence from a nationally representative sample of adults from April-October 2020. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamenghi, L.; Barello, S.; Boccia, S.; Graffigna, G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: The forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.F.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, H.U. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Pakistan: An echo of previous immunizations or prospect of change? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Feng, H.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Willingness to pay and financing preferences for COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.; Harris, K.M.; Parker, A.; Lurie, N. Does receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine predict intention to receive novel H1N1 vaccine: Evidence from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults. Vaccine 2009, 27, 5732–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Eastwood, K.; Durrheim, D.N.; Jones, A.; Butler, M. Acceptance of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza vaccination by the Australian public. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sypsa, V.; Livanios, T.; Psichogiou, M.; Malliori, M.; Tsiodras, S.; Nikolakopoulos, I.; Hatzakis, A. Public perceptions in relation to intention to receive pandemic influenza vaccination in a random population sample: Evidence from a cross-sectional telephone survey. Eurosurveillance 2009, 14, 19437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Alias, H.; Danaee, M.; Wong, L.P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Wong, P.F.; Lee, H.Y.; AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.J. Predicting young adults’ intentions to get the H1N1 vaccine: An integrated model. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: San Fracisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem. Fund. Q. 1966, 44, 94–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frew, E.J.; Wolstenholme, J.L.; Whynes, D.K. Comparing willingness-to-pay: Bidding game format versus open-ended and payment scale formats. Health Policy 2004, 68, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press Conference of the Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism of the State Council on 13 January 2021. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/gwylflkjz145/index.htm (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Zhao, Y.M.; Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Yan, W.; Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y.B.; Lu, Z.A.; Liu, L.; Ni, S.Y.; Su, S.Z.; et al. Public willingness and determinants of COVID-19 vaccination at the initial stage of mass vaccination in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreps, S.; Prasad, S.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hswen, Y.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Zhang, B.; Kriner, D.L. Factors Associated with US Adults’ Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Xu, R.H.; Wong, E.L.; Hung, C.T.; Feng, D.; Feng, Z.; Yeoh, E.K.; Wong, S.Y. Public preference for COVID-19 vaccines in China: A discrete choice experiment. Health Expect 2020, 23, 1543–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullard, A. COVID-19 vaccine development pipeline gears up. Lancet 2020, 395, 1751–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijtregtop, E.A.; Wilschut, J.; Koelma, N.; Van Delden, J.J.; Stolk, R.P.; Van Steenbergen, J.; Broer, J.; Wolters, B.; Postma, M.J.; Hak, E. Which factors are important in adults’ uptake of a (pre)pandemic influenza vaccine? Vaccine 2009, 28, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, J.T.; Yeung, N.C.; Choi, K.C.; Cheng, M.Y.; Tsui, H.Y.; Griffiths, S. Factors in association with acceptability of A/H1N1 vaccination during the influenza A/H1N1 pandemic phase in the Hong Kong general population. Vaccine 2010, 28, 4632–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanda, S.; Osborne, V.; Lynn, E.; Shakir, S. Postmarketing studies: Can they provide a safety net for COVID-19 vaccines in the UK? BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.M.; Romero, J.R.; Bell, B.P. Postapproval Vaccine Safety Surveillance for COVID-19 Vaccines in the US. JAMA 2020, 324, 1937–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Van Rooyen, H.; Wiysonge, C.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: How can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Jie, C.; Yue, D.; Fang, H.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y. Determinants of willingness to pay for self-paid vaccines in China. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4471–4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Rong, H.; Ma, X.; Hou, Z.; Li, S.; Jing, R.; Zhang, H.; Peng, Z.; Feng, L.; Fang, H. Willingness to Pay for Seasonal Influenza Vaccination among Children, Chronic Disease Patients, and the Elderly in China: A National Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2020, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G.; Wyatt, J. Using the Internet for surveys and health research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2002, 4, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyatt, J.C. When to use web-based surveys. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2000, 7, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Bijmolt, T.H.A. Accurately measuring willingness to pay for consumer goods: A meta-analysis of the hypothetical bias. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Booster Vaccination Acceptance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Column % | Row % | |

| Total | 1145 | 100.00 | 84.80 |

| Age group, years | |||

| 18–30 | 349 | 30.48 | 87.11 |

| 31–40 | 403 | 35.20 | 86.85 |

| 41–50 | 284 | 24.80 | 79.23 |

| 51–59 | 109 | 9.52 | 84.40 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 569 | 49.69 | 86.64 |

| Female | 576 | 50.31 | 82.99 |

| Maternal status | |||

| Married | 906 | 79.13 | 85.32 |

| Never married/divorced/widowed | 239 | 20.87 | 82.85 |

| Education level | |||

| Senior high school/technical school or below | 311 | 27.16 | 86.82 |

| College/associate/bachelor’s degree or above | 834 | 72.84 | 84.05 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1000 | 87.34 | 86.30 |

| Retired/out of work/still a student | 145 | 12.66 | 74.48 |

| Household annual income | |||

| ≤100,000 CNY | 352 | 30.74 | 84.09 |

| 100,001–200,000 CNY | 529 | 46.20 | 84.69 |

| >200,000 CNY | 264 | 23.06 | 85.98 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 1013 | 88.47 | 84.60 |

| Rural | 132 | 11.53 | 86.36 |

| Region | |||

| Eastern | 759 | 66.29 | 83.53 |

| Central | 233 | 20.35 | 87.55 |

| Western | 153 | 13.36 | 86.93 |

| Self-reported health status | |||

| Good | 820 | 71.62 | 87.20 |

| Fair/poor | 325 | 28.38 | 78.77 |

| Having any chronic disease | |||

| Yes | 146 | 12.75 | 78.08 |

| No | 999 | 87.25 | 85.79 |

| Priority groups for vaccination | |||

| Yes | 251 | 21.92 | 90.84 |

| No | 894 | 78.08 | 83.11 |

| Received COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Yes | 908 | 79.30 | 89.21 |

| No | 237 | 20.70 | 67.93 |

| Factors | Total | Booster Vaccination Accept | Booster Vaccination Refuse | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Column % | n | Column % | n | Column % | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | |||||||

| The risk of COVID-19 infection | 0.668 | ||||||

| High | 95 | 8.30 | 82 | 8.44 | 13 | 7.47 | |

| Fair/low | 1050 | 91.70 | 889 | 91.56 | 161 | 92.53 | |

| Variants have higher risk of infection than the existing strains | <0.001 | ||||||

| Agree | 978 | 85.41 | 849 | 87.44 | 129 | 74.14 | |

| Neutral/disagree | 167 | 14.59 | 122 | 12.56 | 45 | 25.86 | |

| Perceived severity | |||||||

| The severity of COVID-19 infection | 0.040 | ||||||

| High | 830 | 72.49 | 715 | 73.64 | 115 | 66.09 | |

| Fair/low | 315 | 27.51 | 256 | 26.36 | 59 | 33.91 | |

| Variants can cause more severe illness than the existing strains | <0.001 | ||||||

| Agree | 943 | 82.36 | 822 | 84.65 | 121 | 69.54 | |

| Neutral/disagree | 202 | 17.64 | 149 | 15.35 | 53 | 30.46 | |

| Perceived benefits | |||||||

| Efficacy of boosters against early circulating strains | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 962 | 84.02 | 854 | 87.95 | 108 | 62.07 | |

| Fair/low | 183 | 15.98 | 117 | 12.05 | 66 | 37.93 | |

| Efficacy of boosters to extend protection | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 937 | 81.83 | 829 | 85.38 | 108 | 62.07 | |

| Fair/low | 208 | 18.17 | 142 | 14.62 | 66 | 37.93 | |

| Efficacy of boosters against variants | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 874 | 76.33 | 782 | 80.54 | 92 | 52.87 | |

| Fair/low | 271 | 23.67 | 189 | 19.46 | 82 | 47.13 | |

| Perceived barriers | |||||||

| Safety of boosters | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 958 | 83.67 | 867 | 89.29 | 91 | 52.30 | |

| Fair/low | 187 | 16.33 | 104 | 10.71 | 83 | 47.70 | |

| Worry about serious adverse reaction after vaccination | <0.001 | ||||||

| High | 206 | 17.99 | 152 | 15.65 | 54 | 31.03 | |

| Fair/low | 939 | 82.01 | 819 | 84.35 | 120 | 68.97 | |

| Self-efficacy | |||||||

| It is easy to get the COVID-19 vaccine if wanted | <0.001 | ||||||

| Agree | 845 | 73.80 | 744 | 76.62 | 101 | 58.05 | |

| Neutral/disagree | 300 | 26.20 | 227 | 23.38 | 73 | 41.95 | |

| Cues to action | |||||||

| Used to have confirmed or suspected cases in daily close contacts | 0.353 | ||||||

| Yes | 63 | 5.50 | 56 | 5.77 | 7 | 4.02 | |

| No | 1082 | 94.50 | 915 | 94.23 | 167 | 95.98 | |

| Know about at least one foreign variant | 0.003 | ||||||

| Yes | 984 | 85.94 | 847 | 87.23 | 137 | 78.74 | |

| No | 161 | 14.06 | 124 | 12.77 | 37 | 21.26 | |

| Factors | Unadjusted Logistic Model | Adjusted Logistic Model † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR (aOR) | 95% CI | |

| Received COVID-19 vaccination (yes vs. no) | 3.90 * | (2.77, 5.50) | 3.05 * | (2.05, 4.54) |

| Perceived susceptibility | ||||

| High risk of COVID-19 infection (yes vs. no) | 1.14 | (0.62, 2.10) | 1.00 | (0.48, 2.08) |

| Variants have higher risk of infection than the existing strains (yes vs. no) | 2.43 * | (1.65, 3.58) | 1.03 | (0.59, 1.80) |

| Perceived severity | ||||

| High severity of COVID-19 infection (yes vs. no) | 1.43 * | (1.02, 2.02) | 0.93 | (0.60, 1.43) |

| Variants can cause more severe illness than the existing strains (yes vs. no) | 2.42 * | (1.67, 3.49) | 1.14 | (0.67, 1.96) |

| Perceived benefits | ||||

| High efficacy of boosters against early circulating strains (yes vs. no) | 4.46 * | (3.11, 6.41) | 1.86 * | (1.11, 3.13) |

| High efficacy of boosters to extend protection (yes vs. no) | 3.57 * | (2.50, 5.09) | 1.64 * | (1.04, 2.61) |

| High efficacy of boosters against variants (yes vs. no) | 3.69 * | (2.63, 5.17) | 1.30 | (0.81, 2.10) |

| Perceived barriers | ||||

| Low safety of boosters (yes vs. no) | 0.13 * | (0.09, 0.19) | 0.21 * | (0.13, 0.35) |

| Worry about serious adverse reaction after vaccination (yes vs. no) | 0.41 * | (0.29, 0.59) | 0.63 * | (0.41, 0.97) |

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| It is easy to get the COVID-19 vaccine if wanted (yes vs. no) | 2.37 * | (1.69, 3.32) | 1.24 | (0.79, 1.93) |

| Cues to action | ||||

| Used to have confirmed or suspected cases in daily close contacts (yes vs. no) | 1.46 | (0.65, 3.26) | 2.77 | (0.98, 7.82) |

| Know about at least one foreign variant (yes vs. no) | 1.85 * | (1.23, 2.78) | 1.20 | (0.70, 2.06) |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age group, years (vs. 18–30) | ||||

| 31–40 | 0.98 | (0.64, 1.50) | 0.91 | (0.51, 1.60) |

| 41–50 | 0.57 * | (0.37, 0.86) | 0.52 * | (0.29, 0.91) |

| 51–59 | 0.80 | (0.44, 1.47) | 0.97 | (0.46, 2.04) |

| Female (vs. male) | 0.75 | (0.54, 1.04) | 0.76 | (0.52, 1.10) |

| Married (vs. never married/divorced/widowed) | 1.20 | (0.82, 1.77) | 1.01 | (0.58, 1.75) |

| College/associate/bachelor’s degree or above (vs. senior high school/technical school or below) | 0.80 | (0.55, 1.17) | 0.49 * | (0.30, 0.81) |

| Employed (vs. retired/out of work/still a student) | 2.16 * | (1.43, 3.27) | 1.84 * | (1.06, 3.20) |

| Household annual income (vs. ≤100,000 CNY) | ||||

| 100,001–200,000 CNY | 1.05 | (0.72, 1.52) | 0.92 | (0.58, 1.45) |

| >200,000 CNY | 1.16 | (0.74, 1.82) | 1.16 | (0.64, 2.09) |

| Residing in urban areas (vs. rural) | 0.87 | (0.51, 1.47) | 0.81 | (0.42, 1.55) |

| Region (vs. eastern) | ||||

| Central | 1.39 | (0.90, 2.14) | 1.26 | (0.76, 2.10) |

| Western | 1.31 | (0.79, 2.18) | 1.71 | (0.96, 3.06) |

| Self-reported health status (good vs. fair/poor) | 1.84 * | (1.31, 2.57) | 0.80 | (0.53, 1.23) |

| Having any chronic disease (yes vs. no) | 0.59 * | (0.38, 0.91) | 0.60 | (0.33, 1.06) |

| Belonging to priority groups for vaccination (yes vs. no) | 2.02 * | (1.27, 3.20) | 1.98 * | (1.13, 3.46) |

| WTP Value (CNY) a | n | Percent (%) | Cumulative Percent (%) | Cumulative Percent of Non-Refusers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refusing to vaccinate boosters and report WTP | 82 | 7.2 | 7.2 | - |

| 0 | 374 | 32.7 | 39.8 | 35.2 |

| 1~49 | 59 | 5.2 | 45.0 | 40.7 |

| 50 | 95 | 8.3 | 53.3 | 49.7 |

| 51~99 | 26 | 2.3 | 55.5 | 52.1 |

| 100 | 201 | 17.6 | 73.1 | 71.0 |

| 101~199 | 27 | 2.4 | 75.5 | 73.6 |

| 200 | 152 | 13.3 | 88.7 | 87.9 |

| 201~299 | 3 | 0.3 | 89.0 | 88.1 |

| 300 | 49 | 4.3 | 93.3 | 92.8 |

| 301~499 | 17 | 1.5 | 94.8 | 94.4 |

| 500 | 34 | 3.0 | 97.7 | 97.6 |

| 501~999 | 14 | 1.2 | 99.0 | 98.9 |

| 1000 | 10 | 0.9 | 99.8 | 99.8 |

| 1001~3000 | 2 | 0.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Mean of WTP | 118.62 CNY | |||

| Median of WTP | 60 CNY | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lai, X.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Jing, R.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Feng, H.; Guo, J.; Fang, H. Public Perceptions and Acceptance of COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9121461

Lai X, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang Y, Jing R, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Guo J, Fang H. Public Perceptions and Acceptance of COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines. 2021; 9(12):1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9121461

Chicago/Turabian StyleLai, Xiaozhen, He Zhu, Jiahao Wang, Yingzhe Huang, Rize Jing, Yun Lyu, Haijun Zhang, Huangyufei Feng, Jia Guo, and Hai Fang. 2021. "Public Perceptions and Acceptance of COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in China: A Cross-Sectional Study" Vaccines 9, no. 12: 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9121461

APA StyleLai, X., Zhu, H., Wang, J., Huang, Y., Jing, R., Lyu, Y., Zhang, H., Feng, H., Guo, J., & Fang, H. (2021). Public Perceptions and Acceptance of COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines, 9(12), 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9121461